Aspartame

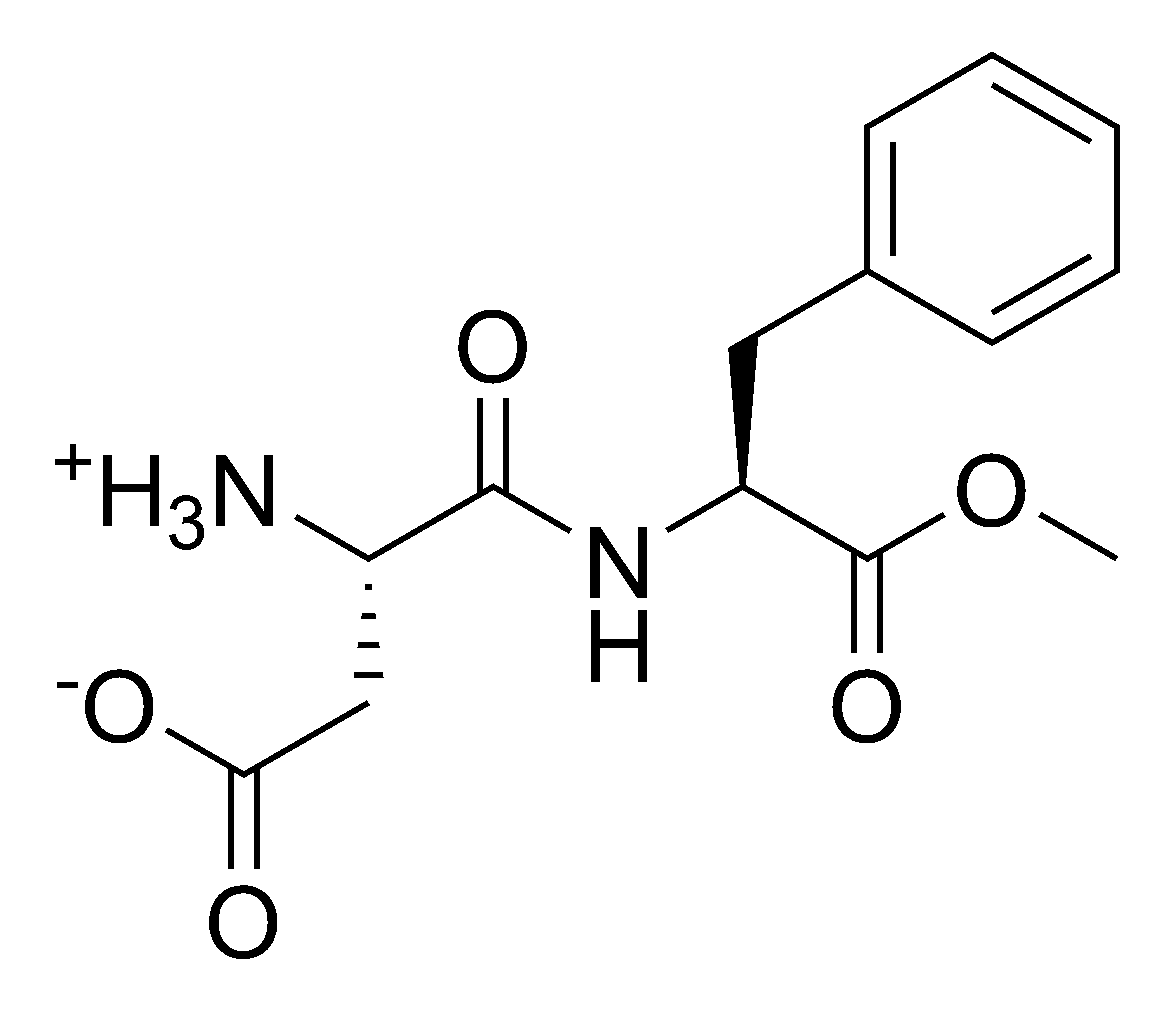

| Aspartame | |

| Chemical name | N-L-a-aspartyl-L-phenylalanine 1-methyl ester |

| Chemical formula | C14H18N2O5 |

| Molecular mass | 294.30 g/mol |

| Melting point | 246 - 247 °C |

| CAS number | 22839-47-0 |

| SMILES | [NH3+][C@@H](CC([O-])=O)C(N[C@@H] (CC1=CC=CC=C1)C(OC)=O)=O |

| |

Aspartame, /ˈæs.pɹ̩ˌtejm, əˈspɑɹˌtejm/, is the name for an artificial, non-carbohydrate sweetener, aspartyl-phenylalanine-1-methyl ester; i.e., the methyl ester of the dipeptide of the amino acids aspartic acid and phenylalanine. It is marketed under a number of trademark names, such as NutraSweet, Equal, and CANDEREL, and is an ingredient of approximately 5,000 consumer foods and beverages sold worldwide. It is commonly used in diet soft drinks, and is often provided as a table condiment. It is also used in some brands of chewable vitamin supplements. However, aspartame is not always suitable for baking, because it often breaks down when heated and loses much of its sweetness. In the European Union, it is also known under the E number (additive code) E951. Aspartame is also one of the sugar substitutes used by diabetics.

Aspartame has been the subject of a vigorous public controversy regarding its safety and the circumstances around its approval. It is well-known that aspartame contains the naturally-occurring amino acid phenylalanine, which is a health hazard to the few people born with phenylketonuria, a genetic inability to process phenylalanine. A few studies have also recommended further investigation into possible connections between aspartame and diseases such as brain tumors, brain lesions, and lymphoma. These findings, combined with notable conflicts of interest in the approval process, have engendered vocal activism regarding the possible risks of aspartame.

Chemistry

Aspartame is the methyl ester of the dipeptide of the natural amino acids L-aspartic acid and L-phenylalanine. Under strongly-acidic or -alkaline conditions, aspartame first generates methanol by hydrolysis. Under more severe conditions, the peptide bonds are also hydrolyzed, resulting in the free amino acids. This methanol point is disputed by some doctors.

Properties and use

Aspartame’s attractiveness as a sweetener comes from the fact that it is approximately 180 times sweeter than sugar in typical concentrations without the high energy value of sugar. While aspartame, like other peptides, has a caloric value of 4 kilocalories (17 kilojoules) per gram, the quantity of aspartame needed to produce a sweet taste is so small that its caloric contribution is negligible, which makes it a popular sweetener for those trying to avoid calories from sugar. The taste of aspartame is not identical to that of sugar: aspartame’s sweetness has a slower onset and longer duration than sugar’s, and some consumers find it unappealing. Blends of aspartame with acesulfame potassium are purported to have a more sugar-like taste, and to be more potent than either sweetener used alone.

Like many other peptides, aspartame may hydrolyze (break down) into its constituent amino acids under conditions of elevated temperature (in the case of aspartame, 86 °C) or high pH. This makes aspartame undesirable as a baking sweetener, and prone to degradation in high-pH products requiring a long shelf life. Aspartame’s stability under heating can be improved to some extent by encasing it in fats or in maltodextrin. Aspartame’s stability when dissolved in water depends markedly on pH. At room temperature, it is most stable at pH 4.3, where its half-life is nearly 300 days. At pH 7, however, its half-life is only a few days. Most soft-drinks have a pH between 3 and 5, where aspartame is reasonably stable. In products that may require a longer shelf life, such as syrups for fountain beverages, aspartame is sometimes blended with a more stable sweetener, such as saccharin.

In products such as powdered beverages, aspartame’s amino group can undergo a Maillard reaction with the aldehyde groups present in certain aroma compounds. The ensuing loss of both flavor and sweetness can be prevented by protecting the aldehyde as an acetal.

Discovery and approval

Aspartame was discovered in 1965 by James M. Schlatter, a chemist working for G.D. Searle & Company. Schlatter had synthesized aspartame in the course of producing an anti-ulcer drug candidate. He discovered its sweet taste serendipitously when he licked his finger, which had accidentally become contaminated with aspartame.

Initial safety testing suggested that aspartame might cause brain tumors in rats; as a result, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not approve its use as a food additive in the United States for many years. In 1980, the FDA convened a Public Board of Inquiry (PBOI) consisting of independent advisors charged with examining the purported relationship between aspartame and brain cancer. The PBOI concluded that aspartame does not cause brain damage, but it recommended against approving aspartame at that time, citing unanswered questions about cancer in laboratory rats. In 1981, U.S. President Ronald Reagan appointed as FDA commissioner Arthur Hull Hayes. Citing data from a single Japanese study that had not been available to the members of the PBOI, Hayes approved aspartame for use in dry goods. [1] In 1983 FDA further approved aspartame for use in carbonated beverages, and for use in other beverages, baked goods, and confections in 1993. It happened that from 1977 to 1985 Donald Rumsfeld served as Chief Executive Officer, President, and then Chairman of G.D. Searle. In 1996, the FDA removed all restrictions from aspartame allowing it to be used in all foods.

In 1985, G.D. Searle was purchased by Monsanto. In this acquisition, Searle’s aspartame business became a separate Monsanto subsidiary, the NutraSweet Company. Monsanto subsequently sold the the Nutrasweet company to J.W. Childs Equity Partners II L.P. on May 25, 2000.[2] The U.S. patent on aspartame expired in 1992, and the aspartame market is now hotly contested between the NutraSweet Company and other manufacturers such as Ajinomoto, Merisant and the Holland Sweetener Company - the latter of which is exiting the business in the fourth quarter of 2006 due to a 'persistently unprofitable business position' because 'global aspartame markets are facing structural oversupply, which has caused worldwide strong price erosion over the last 5 years.' [http://www.marketwire.com/mw/release_html_b1?release_id=115447

Health risks controversy

While it is well-known that aspartame contains phenylalanine and is unsafe for those born with phenylketonuria, research has also indicated more recently that aspartame can be implicated in other public health issues and holds serious health risks.

In 1995, FDA Epidemiology Branch Chief, Thomas Wilcox reported that aspartame complaints represented 75% of all reports of adverse reactions to substances in the food supply from 1981 to 1995. [1] Concerns about aspartame frequently revolve around symptoms and health conditions that are allegedly caused by the sweetener. The 92 health effects reported to the FDA are: abdominal pain, anxiety attacks, arthritis, asthma, asthmatic reactions, bloating/edema, blood sugar control problems (hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia), brain cancer (Pre-approval studies in animals), breathing difficulties, burning eyes or throat, burning urination, inability to think clearly, chest pains, chronic cough, chronic fatigue, confusion, death, depression, diarrhea, dizziness, excessive thirst or hunger, fatigue, feeling “unreal,” flushing of face, hair loss (baldness) or thinning of hair, headaches/migraines, hearing loss, heart palpitations, hives (Urticaria), hypertension (high blood pressure), impotency and sexual problems, inability to concentrate, infection susceptibility, insomnia, irritability, itching, joint pains, laryngitis, “like thinking in a fog,” marked personality changes, memory loss, menstrual problems or changes, muscle spasms, nausea or vomiting, numbness or tingling of extremities, other allergic-like reactions, panic attacks, phobias, poor memory, rapid heartbeat, rashes, seizures and convulsions, slurring of speech, swallowing pain, tachycardia, tremors, tinnitus, vertigo, vision loss, and weight gain. [2]

Questions have been raised about brain cancer, lymphoma, and genotoxic effects such as DNA-protein crosslinks, but these questions are primarily not based on reported case histories.

The sources for reported symptoms and health conditions that have raised questions include:

- Reports and analysis of case histories in scientific journals and at medical conferences

- Symptoms reported to the FDA and other governmental agencies

- Symptoms reported to non-governmental organizations, researchers, and physicians

- Reports of symptoms and health conditions in the media

- Self-reported cases on the Internet.

There is debate in the scientific and medical community as to whether these symptoms are or are not caused by short-term or long-term exposure to aspartame. Some human and animal studies have found adverse effects and some have found no adverse effects. [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]

It is not only the results of the research that have been questioned, but the design of the research that led to specific outcomes. For example, in human research of aspartame, the aspartame is usually provided in slow-dissolving capsules. But the biochemical changes from ingesting aspartame in slow-dissolving capsules are many times smaller than those from ingesting aspartame dissolved in liquids (such as carbonated beverages). [9]

Some human studies provide more than the daily allowance of aspartame, but in an encapsulated form. Based on the above-cited research, the equivalent amount of “real-world” aspartame in these human studies would be less. Other questions that have been raised about aspartame research involving the length of the studies, the number of test subjects, conflict of interest issues, and improper testing procedures.

There are four chemical components of aspartame that have been debated as to whether they are causing or can cause adverse health effects:

Methanol

Approximately 10% of aspartame (by mass) is broken down into methanol in the small intestine. Most of the methanol is absorbed and quickly converted into formaldehyde. Some scientists believe that the methanol cannot be a problem because: (a) there is not enough methanol absorbed to cause toxicity, (b) methanol and formaldehyde are already a by-product of human metabolism, and (c) there is more methanol in some alcoholic beverages and fruit juices than is derived from aspartame ingestion. [10] [11]

Other scientists believe (a) fruit juices and alcoholic beverages always contain protective chemicals such as ethanol that block conversion of methanol into formaldehyde, but aspartame contains no protective factors, (b) the levels of methanol and particularly formaldehyde have been proven to cause chronic toxicity in humans, and (c) the low levels of methanol and formaldehyde in human metabolism are tightly-controlled such that significant increases from aspartame ingestion are not safe. [12], [13]

In 1998, a team of scientists in Spain conducted an experiment on rodents to indirectly measure the levels of formaldehyde adducts in the organs after ingestion of aspartame. They did this by radiolabeling the methanol portion of aspartame. The scientists concluded that formaldehyde bound to protein and DNA accumulated in the brain, liver, kidneys and other tissues after ingestion of either 20 mg/kg or 200 mg/kg of aspartame. [14] However, it has been argued by Tephly that these scientists were not directly measuring formaldehyde, but simply measuring levels of some by-product of the methanol from aspartame. [15] Tephly believes that the by-product was not formaldehyde. The researchers have stated that the data in the experiment have proven it was formaldehyde. [16]

Phenylalanine

Phenylalanine is an amino acid commonly found in foods. Approximately 50% of aspartame (by mass) is broken down into phenylalanine. Because aspartame is metabolized and absorbed very quickly (unlike phenylalanine-containing proteins in foods), it is known that aspartame could spike blood plasma levels of phenylalanine. [17], [18] The debate centers on whether a significant spike in blood plasma phenylalanine occurs at typical aspartame ingestion levels, whether a sudden influx of phenylalanine into the bloodstream adversely affects uptake of other amino acids into the brain and the production of neurotransmitters (since phenylalanine competes with other Large Neutral Amino Acids (LNAAs) for entry into the brain at the blood brain barrier), and whether a significant rise in phenylalanine levels would be concentrated in the brain of fetuses and be potentially neurotoxic.

Based on case histories from aspartame users, measuring levels of neurotransmitters in the brains of animals and measuring the potential of aspartame to cause seizures in animals, some scientists believe that aspartame may affect neurotransmitter production. [19], [20], [21] They believe that even a moderate spike in blood plasma phenylalanine levels from typical ingestion may have adverse consequences in long-term use. They are especially concerned that the phenylalanine can be concentrated in fetal brains to a potentially neurotoxic level. [22], [23] Other scientists believe that rise in blood plasma phenylalanine is negligible in typical use of aspartame [24] and their studies show no significant effects on neurotransmitter levels in the brain or changes in seizure thresholds. [25], [26], [27] In addition, they say that proven adverse effects of phenylalanine on fetuses has only been seen when blood phenylalanine levels stay at high levels as opposed to occasionally being spiked to high levels. [28]

Aspartic acid

Aspartic acid is an amino acid commonly found in foods. Approximately 40% of aspartame (by mass) is broken down into aspartic acid. Because aspartame is metabolized and absorbed very quickly (unlike aspartic acid-containing proteins in foods), it is known that aspartame could spike blood plasma levels of aspartate. [29], [30] Aspartic acid is in a class of chemicals known as excitotoxins. Abnormally high levels of excitotoxins have been shown in hundreds of animals studies to cause damage to areas of the brain unprotected by the blood-brain barrier and a variety of chronic diseases arising out of this neurotoxicity. [31], [32] The debate amongst scientists has been raging since the early 1970s, when Dr. John Olney found that high levels of aspartic acid caused damage to the brains of infant mice [33]. Dr. Olney and consumer attorney, James Turner filed a protest with the FDA to block the approval of aspartame. The debate is complex and has focused on several areas: (a) whether the increase in plasma aspartate levels from typical ingestion levels of aspartame is enough to cause neurotoxicity in one dose or over time, (b) whether humans are susceptible to the neurotoxicity from aspartic acid seen in some animal experiments, (c) whether aspartic acid increases the toxicity of formaldehyde, (d) whether neurotoxicity from excitotoxins should consider the combined effect of aspartic acid and other excitotoxins such as glutamic acid from monosodium glutamate. The neuroscientists at a 1990 meeting of the Society for Neuroscience had a split of opinion on the issues related to neurotoxic effects from excitotoxic amino acids found in some additives such as aspartame. [34]

Some scientists believe that humans and other primates are not as susceptible to excitotoxins as rodents and therefore there is little concern with aspartic acid from aspartame. [35], [36] While they agree that the combined effects of all food-based excitotoxins should be considered [37], their measurements of the blood plasma levels of aspartic acid after ingestion of aspartame and monosodium glutamate demonstrate that there is not a cause for concern. [38], [39] Other scientists feel that primates are susceptible to excitotoxic damage [40] and that humans concentrate excitotoxins in the blood more than other animals. [41] Based on these findings, they feel that humans are approximately 5-6 times more susceptible to the effects of excitotoxins than are rodents. [42] While they agree that typical use of aspartame does not spike aspartic acid to extremely high levels in adults, they are particularly concerned with potential effects in infants and young children [43], the potential long-term neurodegenerative effects of small-to-moderate spikes on plasma excitotoxin levels [44], and the potential dangers of combining formaldehyde exposure from aspartame with excitotoxins given that chronic methanol exposure increases excitoxin levels in susceptible areas of the brain [45], [46] and that excitotoxins may potentiate formaldehyde damage. [47]

Aspartylphenylalanine diketopiperazine

This type of diketopiperazine (DKP) is created in products as aspartame breaks down over time. For example, researchers found that 6 months after aspartame was put into carbonated beverages, 25% of the aspartame had been converted to DKP. [48] Concern amongst some scientists has been expressed that this form of DKP would undergo a nitrosation process in the stomach producing a type of chemical that could cause brain tumors. [49], [50] Other scientists feel that the nitrosation of aspartame or the DKP in the stomach would not produce a chemical that would cause brain tumors. In addition, only a minuscule amount of the nitrosated chemical would be produced. [51] There are very few human studies on the effects of this form of DKP. However, a (one-day) exposure study showed that the DKP was tolerated without adverse effects. [52]

Responses

The American Cancer Society argues that "since aspartame is broken down into these components before it is absorbed into the blood stream, aspartame in its initial form does not have the opportunity to travel to target organs, including the brain, to cause cancer." [53] The Feingold Association has stated that aspartame is reported to cause a variety of neurological effects from headache to seizures and brain tumors.[54] The American Heart Association concludes that "extensive investigation so far hasn’t shown any serious side effects from aspartame." [55] A consumer alert issued by the Association for Consumers Action on Safety and Health was published related to the dangers of ingesting aspartame. [56] The National Cancer Institute argues "there is no evidence that the regulated artificial sweeteners on the market in the United States are related to cancer risk in humans." [57] The National Health Federation calls aspartame a "neurotoxic artificial sweetener." [58] The FDA says the more than "100 toxicological and clinical studies it has reviewed confirm that aspartame is safe for the general population." [59] The consumer organization UK Campaign for Truth in Medicine says that Aspartame is, by far, the most dangerous substance on the market that is added to foods. [60] There have been more than 600 studies on aspartame and thousands of studies on aspartame breakdown products and metabolites. [citation needed] It is not known whether persons writing the opinion for the above-mentioned organizations have read the bulk of the published research on aspartame or whether they are relying on summaries provided to them.

Recently-published research

Since the FDA approved aspartame for consumption in 1981, some researchers have suggested that a rise in brain tumor rates in the United States may be at least partially related to the increasing availability and consumption of aspartame. [61] The results of a large seven-year study into the long-term effects of eating aspartame in rats by the European Ramazzini Foundation for cancer research in Bologna, Italy were released in July 2005. The study of 1,900 rats found evidence that aspartame caused leukemia and lymphoma cancer in female rats. The study showed that there was no statistically significant link between aspartame and brain tumors. [62] The study, published in the European Journal of Oncology, raises concerns about the levels of aspartame exposure. A more recent analysis of the Ramazzini Foundation data published in Environmental Health Perspectives found a link between life-long aspartame consumption in the rats and cancer of the kidney and peripheral nerves. [63]

Manufacturers of aspartame have challenged the validity of the study, citing four earlier cancer studies underwritten by Searle. Other criticisms of the study included the fact that aspartame did not cause cancer in male rats, even at the highest dose, that the lymphoma and leukemia rates in the female controls were abnormally low, and that the rats were allowed to live to spontaneous death instead of the study being terminated at 104-130 weeks like most rodent carcinogenecity studies. Lastly, the conclusions drawn based on a statistically significant increase in combined leukemia and lymphoma rates, rather than either alone, are questionable. [citation needed]

A study published in April 2006 sponsored by the National Cancer Institute involved 340,045 men and 226,945 women, ages 50 to 69, found no statistically significant link between aspartame consumption and leukemias, lymphomas or brain tumors. [64] The study used surveys filled out in 1995 and 1996 detailing food and beverage consumption. The researchers calculated how much aspartame they consumed, especially from sodas or from adding the sweetener to coffee or tea. The researchers report, "Our findings from this epidemiologic study suggest that consumption of aspartame-containing beverages does not raise the risk of hematopoietic or brain malignancies."

Critics of this study point out that while the study looked at humans, it did not look at life-long aspartame consumption as did the Ramazzini study. The Ramazzini study simulated life-long consumption from childhood through old age (e.g., simulating 60 to 90 years of use). The new National Cancer Institute study looked at subjects who consumed diet drinks during a 12-month period from 1995 to 1996. The Ramazzini study had the disadvantage of being an animal study but looked at life-long consumption of aspartame. The National Cancer Institute study was a human study, but only looked at subjects with relatively short-term consumption of diet drinks. Finally, the questionnaire did not ask users to estimate aspartame consumption, only diet drink consumption. [65]

A review of the Ramazzini study by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), published 04 May 2006, concluded that the increased incidence of lymphomas/leukaemias reported in treated rats was unrelated to aspartame, the kidney tumors found at high doses of aspartame were not relevant to humans, and that based on all available scientific evidence to date, there is no reason to revise the previously established Acceptable Daily Intake levels for aspartame.[66]

The European Ramazzini Foundation responded to the EFSA findings by stating that they believed the large difference in incidence of lymphoma and leukemia between the aspartame group and control group signify that these cancers were caused by aspartame ingestion. [67]

Films

- Sweet Misery: A Poisoned World. Directed by Cori Brackett and J. T. Waldron, 2004.

See also

References

- ^ Food Chemical News, June 12, 1995, Page 27.

- ^ Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS). (1993, April 1) Adverse Reactions Associated with Aspartame Consumption (HFS-728). Chief, Epidemiology Branch. Retrieved Oct 24, 2005 from http://www.presidiotex.com/aspartame/Facts/92_Symptoms/92_symptoms.gif (This is an image of part of the document)

External links

Pro-aspartame

- Aspartame Information Center

- Aspartame Information Service

- Aspartame Archives

- Aspartame—American Council on Science and Health

- Sugar Substitutes (U.S. FDA web page)

- Update on Aspartame Safety; EC Scientific Committee on Food (263 KB PDF)

- Health Canada

- GreenFacts.org: Review of the EC Scientific Committee’s 2002 Update

Anti-aspartame

- Aspartame Support Group

- Aspartame Toxicity Information Center

- Aspartame—Dorway to Discovery

- How Excitotoxins Were Discovered

- Excitotoxins—MSG and Aspartame

- Aspartame—Mission Possible News/Articles

- Aspartame Consumer Safety Network

- Aspartame—Former U.S. FDA Investigator

- Sweet Poison

- Update on Aspartame Safety; Response to EC Scientific Committee on Food

- Responses to Aspartame and Its Effects on Health

- Nutrapoison, Part One by Alex Constantine

- Aspartame—Sweetness or Death? by syndicated columnist David Lawrence Dewey

- Ramazzini EU Foundation News & Events