19 equal temperament

In music, 19 equal temperament, called 19-TET, 19-EDO, or 19-ET, is the tempered scale derived by dividing the octave into 19 equal steps (equal frequency ratios). Each step represents a frequency ratio of 21/19, or 63.16 cents (). Because 19 is a prime number, one can use any interval from this tuning system to cycle through all possible notes; just as one may cycle through 12-et on the circle of fifths, the number 7 (of semitones in a fifth in 12-et) being coprime to 12.

History

Division of the octave into 19 steps arose naturally out of Renaissance music theory. The greater diesis, the ratio of four minor thirds to an octave (648:625 or 62.565 cents) was almost exactly a 19th of an octave. Interest in such a tuning system goes back to the sixteenth century, when composer Guillaume Costeley used it in his chanson Seigneur Dieu ta pitié of 1558. Costeley understood and desired the circulating aspect of this tuning. In 1577, music theorist Francisco de Salinas in effect proposed it. Salinas discussed 1/3-comma meantone, in which the fifth is of size 694.786 cents. The fifth of 19-tet is 694.737, which is less than a twentieth of a cent narrower, imperceptible and less than tuning error. Salinas suggested tuning nineteen tones to the octave to this tuning, which fails to close by less than a cent, so that his suggestion is effectively 19-tet. In the nineteenth century, mathematician and music theorist Wesley Woolhouse proposed it as a more practical alternative to meantone temperaments he regarded as better, such as 50 equal temperament.[2]

The composer Joel Mandelbaum wrote his Ph.D. thesis (1961) on the properties of the 19-et tuning, and advocated for its use. In his thesis, he demonstrated why he believed that this system represents the only viable system with a number of divisions between 12 and 22, and furthermore that the next smallest number of divisions resulting in a significant improvement in match to natural intervals is the 31 equal temperament.[4] Mandelbaum and Joseph Yasser have written music with 19-et.[5] Easley Blackwood believes that 19 equal temperament makes possible, "a substantial enrichment of the tonal repertoire."[6]

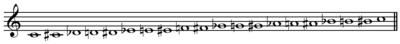

Scale diagram

The 19-tone system can be represented with the traditional letter names and system of sharps and flats by treating flats and sharps as distinct notes, but identifying B♯ as enharmonic with C♭ and E♯ with F♭. With this interpretation, the 19 notes in the scale become:

| Step (cents) | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Note name | A | A♯ | B♭ | B | B♯/ C♭ |

C | C♯ | D♭ | D | D♯ | E♭ | E | E♯/ F♭ |

F | F♯ | G♭ | G | G♯ | A♭ | A | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Interval (cents) | 0 | 63 | 126 | 189 | 253 | 316 | 379 | 442 | 505 | 568 | 632 | 695 | 758 | 821 | 884 | 947 | 1011 | 1074 | 1137 | 1200 | ||||||||||||||||||||

The fact that traditional western music maps unambiguously onto this scale makes it easier to perform such music in this tuning than in many other tunings.

Interval size

Here are the sizes of some common intervals and comparison with the ratios arising in the harmonic series; the difference column measures in cents the distance from an exact fit to these ratios. For reference, the difference from the perfect fifth in the widely used 12 equal temperament is 1.955 cents, and the difference from the major third is 13.686 cents.

| Interval Name | Size (steps) | Size (cents) | Midi | Just Ratio | Just (cents) | Midi | Error (cents) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect fifth | 11 | 694.74 | 3:2 | 701.96 | −7.22 | ||

| Greater tridecimal tritone | 10 | 631.58 | 13:9 | 636.62 | −5.04 | ||

| Greater septimal tritone, diminished fifth | 10 | 631.58 | 10:7 | 617.49 | +14.09 | ||

| Lesser septimal tritone, augmented fourth | 9 | 568.42 | 7:5 | 582.51 | −14.09 | ||

| Lesser tridecimal tritone | 9 | 568.42 | 18:13 | 563.38 | +5.04 | ||

| Perfect fourth | 8 | 505.26 | 4:3 | 498.04 | +7.22 | ||

| Tridecimal major third | 7 | 442.11 | 13:10 | 454.12 | −10.22 | ||

| Septimal major third | 7 | 442.11 | 9:7 | 435.08 | +7.03 | ||

| Major third | 6 | 378.95 | 5:4 | 386.31 | −7.36 | ||

| Inverted 13th harmonic | 6 | 378.95 | 16:13 | 359.47 | +19.48 | ||

| Minor third | 5 | 315.79 | 6:5 | 315.64 | +0.15 | ||

| Septimal minor third | 4 | 252.63 | 7:6 | 266.87 | −14.24 | ||

| Tridecimal 5/4-tone | 4 | 252.63 | 15:13 | 247.74 | +4.89 | ||

| Septimal whole tone | 4 | 252.63 | 8:7 | 231.17 | +21.46 | ||

| Whole tone, major tone | 3 | 189.47 | 9:8 | 203.91 | −14.44 | ||

| Whole tone, minor tone | 3 | 189.47 | 10:9 | 182.40 | +7.07 | ||

| Greater tridecimal 2/3-tone | 2 | 126.32 | 13:12 | 138.57 | −12.26 | ||

| Lesser tridecimal 2/3-tone | 2 | 126.32 | 14:13 | 128.30 | −1.98 | ||

| Septimal diatonic semitone | 2 | 126.32 | 15:14 | 119.44 | +6.88 | ||

| Diatonic semitone, just | 2 | 126.32 | 16:15 | 111.73 | +14.59 | ||

| Septimal chromatic semitone | 1 | 63.16 | 21:20 | 84.46 | −21.31 | ||

| Chromatic semitone, just | 1 | 63.16 | 25:24 | 70.67 | −7.51 | ||

| Septimal third-tone | 1 | 63.16 | 28:27 | 62.96 | +0.20 |

See also

Sources

- ^ Myles Leigh Skinner (2007). Toward a Quarter-tone Syntax: Analyses of Selected Works by Blackwood, Haba, Ives, and Wyschnegradsky, p.52. ISBN 9780542998478.

- ^ a b Woolhouse, W. S. B. (1835). Essay on Musical Intervals, Harmonics, and the Temperament of the Musical Scale, &c.. J. Souter, London.

- ^ http://tonalsoft.com/enc/number/19edo.aspx

- ^ C. Gamer, Some Combinational Resources of Equal-Tempered Systems. Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring, 1967), pp. 32–59

- ^ Myles Leigh Skinner (2007). Toward a Quarter-tone Syntax: Analyses of Selected Works by Blackwood, Haba, Ives, and Wyschnegradsky, p.51n6. ISBN 9780542998478. Cites Leedy, Douglas (1991). "A Venerable Temperament Rediscovered", Persepctives of New Music 29/2, p.205.

- ^ Skinner 2007, p.76.

Further reading

- Levy, Kenneth J.,Costeley's Chromatic Chanson, Annales Musicologues: Moyen-Age et Renaissance, Tome III (1955), pp. 213–261.

External links

- M. Joel Mandelbaum, 1961, Multiple Division of the Octave and the Tonal Resources of 19-tone Temperament

- Bucht, Saku and Huovinen, Erkki, Perceived consonance of harmonic intervals in 19-tone equal temperament

- Darreg, Ivor, "A Case For Nineteen", Sonic-Arts.org.

- Howe, Hubert S. Jr., "19-Tone Theory and Applications", Aaron Copland School of Music at Queens College.

- Sethares, William A., "Tunings for 19 Tone Equal Tempered Guitar", Experimental Musical Instruments, Vol. VI, No. 6, April 1991.

- Hair, Bailey, Morrison, Pearson and Parncutt, "Rehearsing Microtonal Music: Grappling with Performance and Intonational Problems" (project summary), Microtonalism.

- ZiaSpace.com - 19tet downloadable mp3s by Elaine Walker of Zia and D.D.T.

- "The Music of Jeff Harrington", Parnasse.com. Jeff Harrington is a composer who has written several pieces for piano in the 19-TET tuning, and there are both scores and MP3's available for download on this site.

- [1] Chris Vaisvil: GR-20 Hexaphonic 19-ET Guitar Improvisation

- [2] Arto Juani Heino: Artone 19 Guitar Design, naming the 19 note scale Parvatic