Bhumihar

Bhumihar Brahmins

{{Infobox ethnic group

-

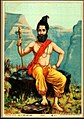

Parashurama

-

Caption2

|group =

|population = Unknown

|popplace =

|languages = Hindi, Bhojpuri, Magadhi, Maithili, Angika, Vajjika, Bundeli[1]

|religions = ![]() Hinduism

|related = Kanyakubja Brahmins Saryupareen Brahmins

|footnotes = Commonly called Babhan

}}

Bhumihar or Babhan or Bhuin-har is a Hindu Brahmin community mainly found in the Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bengal, Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh and Nepal.[1][2][3][4]

Hinduism

|related = Kanyakubja Brahmins Saryupareen Brahmins

|footnotes = Commonly called Babhan

}}

Bhumihar or Babhan or Bhuin-har is a Hindu Brahmin community mainly found in the Indian states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bengal, Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh and Nepal.[1][2][3][4]

Varna status

The Bhumihars are classified in the Brahmin varna of the Indian caste system and traditionally are landowners.[5][6] Their land has been acquired at different times through grants by kings or during the rule of Brahmin kings.[5][7][8][9]

"Kanyakubj Vanshavali" mentions five branches of Kanyakubja Brahmins as Saryupareen, Sanadhya, Bhumihar, Jujhautiya and Prakrit Kanaujia:

Saryupari Sanadhyashcha Bhumiharo Jijhoutayah

Prakritashcha Iti Panchabhedastasya Prakartitah

The Kanyakubja Mahati Sabha, an association of Kanyakubja Brahmins, determined at its 19th and 20th national conventions in 1926 and 1927 that the Bhumihars are among the Kanyakubja Brahmin communities, which also include the Sanadhya, Pahadi, Jujhoutia, Saryupareen, Chattisgarhi, Bhumihar and various Bengali Brahmins.[11]

First modern Indologist of Indian origin, and a key figure in the Bengal Renaissance, Rajendralal Mitra writes about the five branches of Kanyakubja Brahmins as Saryupareen, Sanadhya, Bhumihar, Jujhoutia and Prakrit Kanaujia or Kanyakubj proper.[12]

Bhumihars have been the traditional priests at Vishnupad Mandir in Gaya as Gayawar Pandas and in the adjoining districts like Hazaribagh.[1] The Kingdom of Kashi belonged to Bhumihar Brahmins and big zamindari like Bettiah Raj, Hathwa Raj, Pandooi Raj and Tekari Raj, Sheohar Raj, Ram Nagar belonged to them. Bhumihars were well respected Brahmins in the courts of Dumraon Maharaj, King of Nepal and Raj Darbhanga.[1] Some Mohyal Brahmins migrated eastward and are believed to constitute some sub-divisions of Bhumihars, some of whom are also descendants of Husseini Brahmins and mourn the death of Imam Hussain.[13] There is also a significant migrant population of Bhumihars in Mauritius,[14] Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and others.

Bhumihars are commonly called Babhans[15][16][17] which is the Pali word for Brahmins[18][19] and is used to refer to Brahmins in Buddhist sources.[19][20]

Origin and history

Mythology

When Parashurama destroyed the Kshatriya race, and he set up in their place the descendants of Brahmins, who, after a time, having mostly abandoned their priestly functions, took to land-owning (Zamindari).[21][22] Lord Parashurama was the first Bhumihar.[21][22]

Genetics

Research was done in 2003 on the genetic profile of members of the Bhumihar Brahmin and other Brahmins. The Bhumihar caste " was found clustering with the Brahmin group as expected, since Bhumihar is known to be a subclass of Brahmin."[23]

Etymology

The literal meaning of Bhumihar is Bhumi – "Land", kara or hara – "maker" in Sanskrit.[24] In the language of the Indian feudal system, Bhum is the name given to a kind of tenure similar to the Inams and Jagirs of Mohammedan times.[24] By a Bhum, according to the Rajputana gazetteer, a hereditary, non-resumable and inalienable property in the soil was inseparably bound up with the revenue-free title.[24] The meaning of the designation Bhumihar being as stated above, the Bhumihar Brahmins are evidently those Brahmins who held grants of land for secular services.[24] Bhum was given as compensation for bloodshed in order to quell a feud for distinguished services in the field, for protection of services in the field, for protection of a border, or for the watch and ward of a village.[24]

History

By the 16th century, Bhumihars known as "karm kandi pandit" controlled vast stretches of territory, particularly in North Bihar.[25] In South Bihar, their most prominent representative was the Tekari family, whose large estate in Gaya dates back to the early 18th century.[25] With the decline of Mughal Empire, in the area of south of Avadh, in the fertile rive-rain rice growing areas of Benares, Gorakhpur, Deoria, Ghazipur, Ballia and Bihar and on the fringes of Bengal, it was the 'military' or Bhumihar Brahmins who strengthened their sway.[26] The distinctive 'caste' identity of Bhumihar Brahman emerged largely through military service, and then confirmed by the forms of continuous 'social spending' which defined a man and his kin as superior and lordly.[27] In 19th century, many of the Bhumihar Brahmins were zamindars. Of the 67000 Hindus in the Bengal Army in 1842, 28000 were identified as Rajputs and 25000 as Brahmins, a category that included Bhumihar Brahmins.[28] The Brahmin presence in the Bengal Army was reduced in the late 19th century because of their perceived primary role as mutineers in the Mutiny of 1857,[28] led by Mangal Pandey. Now, a majority of them are farmers with some big land-holders.

Some Bhumihars had settled in Chandipur, Murshidabad, Bardhaman during late 19th and early 20th centuries where they are at the top of the social hierarchy.[29]

Pandit Jogendra Nath Bhattacharya in his book Hindu Castes and Sects published in 1896, went on to write about the origin of Bhumihar Brahmins of Bihar and Banaras[21] as: "The clue to the exact status of the Bhumihar Brahmans is afforded by their very name. The word literally means a landholder. In the language of the Indian feudal systems, Bhoom is the name given to a kind of tenure similar to the Inams and Jagirs of Mohammedan times. By a Bhoom, according to the Rajputana Gazeteer, an hereditary, non-resumableand inalienable property in soil was inseparably bound up with a revenue-free title. Bhoom was given as a compensation for bloodshedin order to quell a feud, for distinguished services in the field, for protection of a border or for the watch and ward of the village. The meaning of the designation Bhumihar being as stated above, the Bhumihar Brahmans are evidently these Brahmans who held grants of land for secular service. Whoever held a secular fief was Bhumihar. Where a Brahman held such a tenure, he was called a Bhumihar Brahman....Bhumihar Brahmans are sometimes called simply Bhumihars..."

They perform all their religious ceremonies in the same manner as other Brahmins, but as they also practice secular occupations like the Laukik Brahmans of Southern India, they are not entitled to accept religious gifts or to minister to anyone as priest. The usual surnames/titles of the Bhumihar Brahmins are same as those of other Brahmins of Northern India. Being a fighter by caste few of them have Rajputana surnames/titles.[11][24] The general editor of the book "People of India (Bihar and Jharkhand)", published by Anthropological Survey of India (ASI), and noted academician-bureaucrat, the late Kumar Suresh Singh, said that the surname Singh, which used to denote connection with power and authority, was used in Bihar by Brahmin zamindars, like the surname "Khan" in Muslims.[30]

Before independence, it was the custom of the Bhumihar Brahmins to stage an elaborate Kālī puja, during which annual payments were made to servants and gifts of cloth were distributed to dependents, both Hindu and Muslim.[29]

M. A. Sherring in his book Hindu Tribes and Castes as Reproduced in Benaras[31] published in 1872, mentions, "Great important distinctions subsist between the various tribes of Brahmins. Some are given to learning, some to agriculture, some to politics and some to trades. The Maharashtra Brahmin is very different being from the Bengali, while the Kanaujia (Kanyakubja Brahmins) differs from both. Only those Brahmins who perform all six duties are reckoned perfectly orthodox. Some perform three of them, namely, the first, third and fifth and omit the other three. Hence Brahmins are divided into two kinds, the Shat-karmas and the tri-karmas or those who perform only three. The Bhumihar Brahmins for instance are tri-karmas, and merely pay heed to three duties. The Bhumihars, of whom many, though not all, belong to the Saryupareen Brahmin division, are a large and influential body in all that province (United Province)."

Bhumihars were referred to as "Military Brahmin" by Francis Buchanan and as "Magadh Brahmin" by William Adam in 1883.[32] William Crooke in his book, Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh,[33] has mentioned Bhuinhar as an important tribe of landowners and agriculturists in eastern districts and that they are also known as Babhan, Zamindar Brahman, Grihastha Brahman, or Pachchima or 'western' Brahmans.

Gorakh Rai, a scion of the Brahmin Shahi (Brahmin Shahi dynasty) family, was killed while fighting alongside Prithvi Raj Chauhan against Mohammad Ghauri at Taraori, in 1192 CE. Gorakh Rai’s descendants are among the present day Vaid Caste of Mohyal Brahmins and they still prefix the honorific Raizada (prince) to their names. Another branch of this clan, that first set up residence at a place called Jai Theriya near Lucknow, later moved east and established a state at Bettiah in Bihar. They were known as Jaitheriyas, now a sect of Bhumihar Brahmins.[34]

In 1889, Pradhan Bhumihar Brahman Sabha was established at Patna "to improve moral, social and educational reforms of the community."[35] The social reformation among Bhumihar Brahmins had two streams – one led by Sir Ganesh Dutt, and the other by Swami Sahajanand Saraswati.[32] Bhumihars were officially recognised as Brahmins by the government of British India in 1911 census (second all India census report) of British India.[36]

Harry W. Blair notes that the Bhumihars were

a high-caste community which has at least since the beginning of the 19th century claimed that it was in fact and should be regarded as a Brahman caste. In the early years of the [20th] century the Bhumihars organized a caste association, the Bhumihar Brahman Sabha, to press this claim, in particular with the census authorities. The census officials felt themselves besieged by these efforts and tried, valiantly in their own estimation, to thwart them, but not always successfully.[37]

Blair's conclusion from analysis of census data in the Bihar area for 1901–1931 is that Bhumihars had begun to pass themselves off to census enumerators as being Brahman, evidenced by a fall in the number of Bhumihars recorded occurring at the same time as there was a substantial rise in the number of Brahmins. In some areas the change was "quite spectacular". He also notes that of all the various caste associations in this area it was only that of the Bhumihars which had organised with the intent of achieving "the promotion of its members to a different higher caste,"[37]

Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, a Bhumihar himself, wrote extensively on Brahmin society and on the origin of Bhumihars. He stated that the Bhumihars are among the superior Brahmins.[38] Some Bhumihar Brahmins are also known for their secular and unorthodox practices, where some of them are also descendants of Husseini Brahminss.[13] On the social scale, although the Bhumihars are known to be Brahmins, on account of the fact that they were cultivators they were not given the ritual status of Brahmins.[39]

Siyaram Tiwari, the former dean at Visva Bharati University, stated that the Bhumihars are "landed Brahmins who stopped taking alms and performing pujas and rituals", These are Tyagis of Western UP, Zamindar Bengali Brahmins, Niyogi Brahmins of Andhra Pradesh, Nambudiri Brahmin of Kerala, Chitpavans of Maharashtra, Anavil Desais of Gujarat and Mohyals of Punjab.[40] Bhumihars are classified in the Brahmin varna in Hinduism and hence use the designation Bhumihar Brahmin.[6]

Acharya Tarineesh Jha, himself a Maithil Brahmin scholar has attested how from ancient times to modern all great Brahmin scholars like Maithili Manishi Mahamahopadhyay Chitradhar Mishra, Mahamahopadhyay Balkrishna Mishra; Saryupareen Brahmin scholars Mahamahopadhyay Dwivedi, Mahamahopadhyay Shivkumar Shastri, Dr. Hazari Prasad Dwivedi; Kanyakubja Brahmins scholars Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi, Pandit Laxminarayan Dixit Shastri, Pandit Venkatesh Narayan Tiwari and others have mentioned about Bhumihar Brahmins as their fellow Brahmin brothers.[41]

They are also called Ajachak Brahmans, i.e., Brahmans who do not take alms (jachak) in contrast to the ordinary Brahmans who are Jachaks or almstakers[42] but there are still some who traditionally take alms as in Gaya and Hazaribagh.[43] Like fellow Brahmans, they did not use to hold the plough, but employed labourers for the purpose.[42]

Social organisation

The census returns give no less than four hundred and fifty-eight sections: but here the territorial sections and the Brahminical gotras are mixed up together.[33] The most important local sections are the Gautama, and Kolaha in Banaras; the Gautama in Mirzapur; Bhriguvanshi, , Donwar, Gautama, Kinwar, Kistwar, Sakarwar, Sonwar, in Ghazipur; Bhagata, Kinwar, Benwar, of Ballia; the Baghochhiya, Baksaria, Gautama, Kaushik and Sakarwar (Sankritya) of Gorakhpur; the Barasi, Birhariya of Basti; and the Barwar, Bharadwaj,parashar of siwan , Denwar, Gargbans, Gautama, Purvar, Sakarwar, and Shandilya of Azamgarh.[33] On the Jijhoutia clan of Bhumihar Brahmins, William Crooke writes, "A branch of the Kanaujia Brahmins (Kanyakubja Brahmins) who take their name from the country of Jajakshuku, which is mentioned in the Madanpur inscription."[33]

Domestic ceremonies and religious beliefs

The Bhumihar Brahmins follow in every respect the standard Brahminical rules.[33] They are usually Shaivas and Shaktas.[33] There are also Vaishnavas, following the Tatvavada school of Madhavacharya.[44] Bhumihar Brahmins, like all other Brahmins are endogamous, but marital relations are known to exist since ancient times between Bhumihar Brahmins and Maithil Brahmins in Tirhut and Mithila and between Bhumihar Brahmins and Kanyakubja Brahmins in Bundelkhand region of Madhya Pradesh where Jihoutia clan of Bhumihar Brahmins live.[43] Bhumihar Brahmin men of Purnea took to Maithil Brahmin wives in Purnea and married their daughters to Bhumihar Brahmin/Babhan men.[45][46]

Political and social movements

Bhumihars are considered a politically volatile community.[47][48] Bhumihar Brahmins in Champaran had revolted against indigo cultivation in 1914 (at Pipra) and 1916 (Turkaulia) and Pandit Raj Kumar Shukla took Mahatma Gandhi to Champaran and the Champaran Satyagraha began.[49]

Some Notable Bhumihar-Brahmins Personalities

Government Agency

- Ram Sharan Sharma-was an eminent historian of Ancient and early Medieval India.

Freedom Fighters

- Mangal Pandey-one of the earliest independence fighters of 1857 from Ballia.

- Sahajanand Saraswati- Freedom Fighter

- Ramdhari Singh Dinkar-Freedom Fighter

- Gauri Shankar Rai-Freedom Fighter ,participated in"QUIT INDIA MOVEMENT".

- Indradeep Sinha- Freedom Fighter

- Ganga Sharan Singh (Sinha)-Eminent nationalist, freedom fighter and litterateur,MP

- Karyanand Sharma- was an eminent nationalist and peasant leader who led movements against zamindars and British.

Politicians

- Krishna Sinha- (affectionately called Sri Babu),Krishna Sinha(1887–1961), known as Sri Babu and Bihar Kesari, was the first Chief Minister of the Indian state of Bihar (1946–1961).

- Gauri Shankar Rai-(MP) member Sixth Lok Sabha during 1977-79 representing Ghazipur constituency of Uttar Pradesh

- Krishnanand Rai-Contractor, MLA (BJP)

- Ramdhari Singh Dinkar-Member of Parliament,Poet, Essayist, Literary critic, Journalist, Satirist, Rashtrakavi ("National poet")

- Nrad Rai-MLA (SP),Ballia

- Upendra tiwari-MLA (BJP),Ballia

Writer/Actor/Actress

- Ramdhari Singh Dinkar-Poet, Essayist, Literary critic, Journalist, Satirist, Rashtrakavi ("National poet")

- Rambriksh Benipuri-Writer, Dramatist, Essayist, Novelist

- Sandali Sinha- Bollywood actress

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d Saraswati, Swami Sahajanand (2003). Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes (in Volume 1). Delhi: Prakashan Sansthan. pp. 519 (Volume 1). ISBN 81-7714-097-3.

- ^ Political Economy and Class Contradictions: A Study – Jose J. Nedumpara – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ Land and Society in India: Agrarian Relations in Colonial North Bihar – Bindeshwar Ram – Google Books. Books.google.co.in. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Social justice and new challenges". Flonnet.com. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ a b Bayly, Christopher Alan (2011). Recovering Liberties: Indian Thought in the Age of Liberalism and Empire (Ideas in Context). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-10-760147-5.

- ^ a b Sinha, Gopal Sharan (September 1967). "Exploration in Caste Stereotypes". Social Forces. 46 (1). University of North Carolina Press: 42–47. JSTOR 2575319.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "Sinha67" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Bhadra, Gautam (2008). Subaltern Studies: Writings on South Asian History and Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-565125-6.

- ^ Alavi, Seema (2007). The Eighteenth Century in India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-569201-3.

- ^ Robb, Peter (2006). Empire, Identity, and India: Peasants, Political Economy, and Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-568160-4.

- ^ Saraswati, Swami Sahajanand (2003). Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes (in Volume 1 at p. 518, Parishist by Acharya Tarineesh Jha, 515–519). Prakashan Sansthan.

- ^ a b Saraswati, Swami Sahajanand (2003). Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes (in Volume 1). Delhi: Prakashan Sansthan. pp. 519 (at p 68–69) (Volume 1). ISBN 81-7714-097-3.

- ^ Saraswati, Swami Sahajanand (2003). Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes (in Volume 1 at p. 518, Parishist by Acharya Tarineesh Jha, 515–519). Prakashan Sansthan. ISBN 81-7714-097-3.

- ^ a b Ahmad, Faizan (21 January 2008). "Hindus participate in Muharram". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ Thapan (ed.), Meenakshi (2005). Transnational Migration and the Politics of Identity. SAGE. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-7619-3425-7.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Sharma, R.S. (2009). Rethinking India's Past. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-569787-2.

- ^ Ram, Bindeshwar (1998). Land and society in India: agrarian relations in colonial North Bihar. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0643-5.

- ^ Diwakar, Ranganath Ramachandra (1959). Bihar through the ages. Orient Longman.

- ^ Gupta, N. L. (1975). Transition from capitalism to socialism, and other essays. Kalamkar Prakashan. ASIN B0000E7XZP.

- ^ a b Guha, Ranajit (2000 (2nd edition)). A Subaltern studies reader, 1986–1995. South Asia Books. ISBN 978-0-19-565230-7.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Maitra, R. K. (1959). Indian Studies: past & present. ASIN B0000CRX5I.

- ^ a b c Jogendra Nath Bhattacharya (1896). Hindu Castes and Sects: AN Exposition of the Origin of the Hindu Caste System. p. 109.

- ^ a b Crooke, William (1999). The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh. 6A, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049, India: Asian Educational Services. pp. 1809 (at page 64). ISBN 81-206-1210-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ USA (24 May 2012). "Genetic profile based upon 15 microsate... [Ann Hum Biol. 2003 Sep–Oct] – PubMed – NCBI". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Sinha, Sushil Kumar (2005). The Bhumihars: Caste of Eastern India. 4855/24, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi-110002, India: Raj Publications. pp. 200(at page 30). ISBN 81-86208-37-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Yang, Anand A. (1999). Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar. University of California Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-520-21100-1.

- ^ Bayly, C.A. (1988). Rulers, Townsmen and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870. Cambridge University Press. pp. 504 (at p 18). ISBN 978-0-521-31054-3.

- ^ Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 440 (at p 203). ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6.

- ^ a b R. G. Tiedemann, Robert A. Bickers (2007). The Boxers, China, and the World. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 231 (at p 63). ISBN 978-0-7425-5395-8.

- ^ a b Nicholas, Ralph W. (2003). Fruits of worship: practical religion in Bengal. Orient Blackswan. pp. 248 (at p 35). ISBN 978-81-8028-006-1.

- ^ "Using surnames to conceal identity". The Times of India. 21 February 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- ^ Sherring, M.A. (First ed 1872, new ed 2008). Hindu Tribes and Castes as Reproduced in Benaras. 6A, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049, India: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-2036-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Pranava K Chaudhary (3 March 2003). "Rishis, Maharshis, Brahmarshis..." The Times of India. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Crooke, William (1999). The Tribes and Castes of the North-Western Provinces and Oudh. Vol. 4. 6A, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi-110049, India: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1210-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Raizada Harichand Vaid, Gulshane Mohyali, Part I, p. 53 and Part II, pp. 134–135.

- ^ ed. by V. S. Upadhyay ... (1995). Contemporary Indian Society: Essays in Honour of Professor Sachchidananda. Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-7041-613-5.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Blunt, E.A.H. (1969) [1931]. The Caste System of North India. S. Chand Publishers.

- ^ a b Blair, Harry W. (1981). "Caste and the British Census in Bihar: Using Old Data to Study Contemporary Political Behavior". In Barrier, Norman Gerald (ed.). The Census in British India: New Perspectives. New Delhi: Manohar. pp. 157–158. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ Saraswati, Swami Sahajanand (2003). Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes(Brahmarshi Vansha Vistar in Volume 1). Delhi: Prakashan Sansthan. pp. 153–519 (Volume 1). ISBN 81-7714-097-3.

- ^ Das, A.N. (1 September 1982). Agrarian Movements in India: Studies on 20th Century Bihar. Routledge. pp. 152 (at p 51). ISBN 978-0-7146-3216-2.

- ^ Arun Kumar (25 January 2005). "Bhumihars rooted to the ground in caste politics". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ Saraswati, Swami Sahajanand (2003). Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes(Brahmarshi Vansha Vistar in Volume 1). Delhi: Prakashan Sansthan. pp. 153–519 at pg. 515–19(Volume 1) Parishisht by Acharya Tarineesh Jha. ISBN 81-7714-097-3.

- ^ a b O'malley, L.S.S. (2007). Bengal District Gazetteer: Gaya. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 504 (at p 18). ISBN 978-81-7268-137-1.

- ^ a b Saraswati, Swami Sahajanand (2003). Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali in Six volumes(Brahmarshi Vansha Vistar in Volume 1). Delhi: Prakashan Sansthan. pp. 153–519. ISBN 81-7714-097-3.

- ^ Chatterjee, Gautam (2003). Sacred Hindu Symbols. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-397-7.

- ^ Administration, District (1915). Purnea District Gazetteer, B Volume: Statistics, 1900–1901 to 1910–1911. Pūrnia (British India: District).

- ^ Roy Choudhury, Pranab Chandra (1965). Bihar District Gazetteers. Printed by the Superintendent, Secretariat Press, Bihar.

- ^ Abhay Singh (6 July 2004). "BJP, Cong eye Bhumihars as Rabri drops ministers". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ These days, their poster boys are goons. Asia Africa Intelligence Wire. 16 March 2004

- ^ Brown, Judith Margaret (1972). Gandhi's Rise to Power, Indian Politics 1915–1922: Indian Politics 1915–1922. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press Archive. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-521-09873-1.

Bibliography

- Swami Sahajanand Saraswati Rachnawali (Selected works of Swami Sahajanand Saraswati), Prakashan Sansthan, Delhi, 2003.

- Baldev Upadhyaya, Kashi Ki Panditya Parampara, Sharda Sansthan, Varanasi, 1985.

- Kautilya Arthashastra, R. P. Kangle, tr. 3 vols. Laurier Books, Motilal Banarsidass, New Delhi (1997) ISBN 81-208-0042-7.

- Olivelle, Patrick (2005). Manu's Code of Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517146-2.

- Translation of Manusmṛti by G. Bühler (1886). Sacred Books of the East: The Laws of Manu (Vol. XXV). Oxford. Available online as The Laws of Manu

- Pandurang Vaman Kane, History of Dharmasastra, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, The Hindu View of Life, Harper Collins, 2009 (first published 1926).

- Christopher Alan Bayly, Rulers, Townsmen, and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion, 1770–1870, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Anand A. Yang, Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar, University of California Press, 1999.

- Peter Robb, Peasants, Political Economy, and Law, Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Seema Alavi, The Eighteenth Century in India, Oxford University Press, 2007

- Acharya Hazari Prasad Dwivedi Rachnawali, Rajkamal Prakashan, Delhi.

- Bibha Jha's PhD thesis Bhumihar Brahmins: A Sociological Study submitted to the Patna University.

- Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi Rachnavali, I to VII volumes, Kitabghar Prakashan, New Delhi.

- Arvind Narayan Das, Agrarian movements in India: studies on 20th century Bihar (Library of Peasant Studies), Routledge, London, 1982.

- M. N. Srinivas, Social Change in Modern India, Orient Longman, Delhi, 1995.