Isobutane

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-Methylpropane[1]

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1730720 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.780 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E943b (glazing agents, ...) | ||

| 1301 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1969 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C4H10 | |||

| Molar mass | 58.124 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | 2.51 mg mL−1 (at 15 °C, 100 kPa) | ||

| Vapor pressure | 204.8 kPa (at 21 °C) | ||

Henry's law

constant (kH) |

8.6 nmol Pa−1 kg−1 | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

96.65 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−134.8–−133.6 kJ mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2.86959–−2.86841 MJ mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H220 | |||

| P210 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | -83 °C | ||

| Explosive limits | 1.4–8.3% | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Isobutane (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

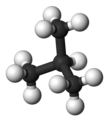

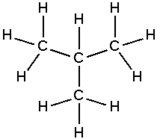

Isobutane (i-butane), also known as methylpropane, is an isomer of butane. It is the simplest alkane with a tertiary carbon. Concerns with depletion of the ozone layer by freon gases have led to increased use of isobutane as a gas for refrigeration systems, especially in domestic refrigerators and freezers, and as a propellant in aerosol sprays. When used as a refrigerant or a propellant, isobutane is also known as R-600a. Some portable camp stoves use a mixture of isobutane with propane, usually 80:20. Isobutane is used as a feedstock in the petrochemical industry, for example in the synthesis of isooctane.[2]

Its UN number (for hazardous substances see shipping) is UN 1969. Isobutane is the R group for the amino acid leucine.

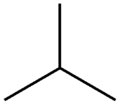

Nomenclature

Isobutane is the trivial name retained by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) in its 1993 Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry.[3] Since the longest continuous chain in isobutane is only three carbon atoms, the systematic name is 2-methylpropane. The position number (2-) is unnecessary because it is the only possibility in methylpropane.

- The two isomers of butane

-

n-Butane

-

Isobutane (methylpropane)

Uses

Isobutane is used as a refrigerant.[4] The use in refrigerators started in 1993 when Greenpeace presented the Greenfreeze project with the German company Foron.[5] In this regard, blends of pure, dry "isobutane" (R-600a) (that is, isobutane mixtures) have negligible ozone depletion potential and very low Global Warming Potential (having a value of 3.3 times the GWP of carbon dioxide) and can serve as a functional replacement for R-12, R-22, R-134a, and other chlorofluorocarbon or hydrofluorocarbon refrigerants in conventional stationary refrigeration and air conditioning systems.

In the Chevron Phillips slurry process for making high-density polyethylene, isobutane is often used as a diluent. As the slurried polyethylene is removed, isobutane is "flashed" off, and condensed, and recycled back into the loop reactor for this purpose.[6]

Isobutane is also used as a propellant for aerosol cans and foam products.

Refrigerant use

As a refrigerant, isobutane has an explosion risk in addition to the hazards associated with non-flammable CFC refrigerants. Reports surfaced in late 2009 suggesting the use of isobutane as a refrigerant in domestic refrigerators was potentially dangerous. Several refrigerator explosions reported in the United Kingdom are suspected to have been caused as a result of isobutane leaking into the refrigerator cabinet and being ignited by sparks in the electrical system.[7] Although unclear how serious this could be, at the time this report came out it was estimated 300 million refrigerators worldwide use isobutane as a refrigerant.

Substitution of this refrigerant for motor vehicle air conditioning systems not originally designed for R600a is widely prohibited or discouraged, on the grounds that using flammable hydrocarbons in systems originally designed to carry non-flammable refrigerant presents a significant risk of fire or explosion.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Vendors and advocates of hydrocarbon refrigerants argue against such bans on the grounds that there have been very few such incidents relative to the number of vehicle air conditioning systems filled with hydrocarbons.[15][16]

References

- ^ "ISOBUTANE - Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 16 September 2004. Identification and Related Records. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Patent Watch, July 31, 2006.

- ^ Panico, R.; & Powell, W. H. (Eds.) (1994). A Guide to IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Compounds 1993. Oxford: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03488-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/93/r93_679.htm - ^ "European Commission on retrofit refrigerants for stationary applications" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Page - March 15, 2010 (2010-03-15). "GreenFreeze". Greenpeace. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kenneth S. Whiteley. "Polyethylene". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_487.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Bingham, John (September 1, 2009). "Exploding fridges: ozone friendly gas theory for mystery blasts". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ "U.S. EPA hydrocarbon-refrigerants FAQ". Epa.gov. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ Compendium of hydrocarbon-refrigerant policy statements, October 2006[dead link]

- ^ "MACS bulletin: hydrocarbon refrigerant usage in vehicles" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ "Society of Automotive Engineers hydrocarbon refrigerant bulletin". Sae.org. 2005-04-27. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ "Saskatchewan Labour bulletin on hydrocarbon refrigerants in vehicles". Labour.gov.sk.ca. 2010-06-29. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ VASA on refrigerant legality & advisability[dead link]

- ^ "Queensland (Australia) government warning on hydrocarbon refrigerants" (PDF). Energy.qld.gov.au. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ "New South Wales (Australia) Parliamentary record, 16 October 1997". Parliament.nsw.gov.au. 1997-10-16. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ "New South Wales (Australia) Parliamentary record, 29 June 2000". Parliament.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 2010-10-29.