Beijing

Beijing

北京 | |

|---|---|

北京市 · Municipality of Beijing | |

Clockwise from top: Tiananmen, Temple of Heaven, National Center for the Performing Arts, and Beijing National Stadium | |

Location of Beijing Municipality within China | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Divisions[1] - County-level - Township-level | 16 districts, 2 counties 289 towns and villages |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • CPC Ctte Secretary | Guo Jinlong |

| • Mayor | Wang Anshun (acting) |

| Area | |

• Municipality | 16,801.25 km2 (6,487.00 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 43.5 m (142.7 ft) |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

• Municipality | 20,693,000 |

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,200/sq mi) |

| • Ranks in China | Population: 26th; Density: 4th |

| Demonym | Beijinger |

| Major ethnic groups | |

| • Han | 96% |

| • Manchu | 2% |

| • Hui | 2% |

| • Mongol | 0.3% |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Postal code | 100000–102629 |

| Area code | 10 |

| GDP[3] | 2011 |

| - Total | CNY 1.6 trillion US$ 247.7 billion (13th) |

| - Per capita | CNY 80,394 US$ 12,447 (3rd) |

| - Growth | |

| HDI (2008) | 0.891 (2nd)—very high |

| License plate prefixes | 京A, C, E, F, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, Q 京B (taxis) 京G, Y (outside urban area) 京O (police and authorities) 京V (in red color) (military headquarters, central government) |

| City trees | Chinese arborvitae (Platycladus orientalis) |

| Pagoda tree (Sophora japonica) | |

| City flowers | China rose (Rosa chinensis) |

| Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium) | |

| Website | www.ebeijing.gov.cn |

Template:Contains Chinese text

| Beijing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 北京 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Běijīng ⓘ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Peking | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Northern capital | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Beijing (/beɪˈdʒɪŋ/; Chinese: 北京; pinyin: Běijīng, [peɪ˨˩ t͡ɕiŋ˥]), sometimes romanized as Peking[4] (/piːˈkɪŋ/, /peɪˈkɪŋ/), is the capital of the People's Republic of China and one of the most populous cities in the world. The population as of 2012 was 20,693,000.[2] The metropolis, located in northern China, is governed as a direct-controlled municipality under the national government, with 14 urban and suburban districts and two rural counties.[5] Beijing Municipality is surrounded by Hebei Province with the exception of neighboring Tianjin Municipality to the southeast.[6]

Beijing is the second largest Chinese city by urban population after Shanghai and is the nation's political, cultural, and educational center.[7] It is home to the headquarters of most of China's largest state-owned companies, and is a major hub for the national highway, expressway, railway, and high-speed rail networks. The Beijing Capital International Airport is the second busiest in the world by passenger traffic.

The city's history dates back three millenia. As the last of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China, Beijing has been the political center of the country for much of the past seven centuries.[8] The city is renowned for its opulent palaces, temples, gardens, tombs, walls and gates,[9] and its art treasures and universities have made it a center of culture and art in China.[9] Few cities in the world have been the political and cultural center of an area as immense for so long.[10]

Etymology

Over the past 3,000 years, the city of Beijing has had numerous other names. The name Beijing, which means "Northern Capital" (from the Chinese characters 北 for north and 京 for capital), was applied to the city in 1403 during the Ming Dynasty to distinguish the city from Nanjing (the "Southern Capital").[11] The English spelling is based on the pinyin romanization of the two characters as they are pronounced in Standard Mandarin. An older English spelling, Peking, is the Postal Map Romanization of the same two characters as they are pronounced in Chinese dialects spoken in the southern port towns first visited by European traders and missionaries.[12] Those dialects preserve the Middle Chinese pronunciation of 京 as kjaeng,[13] prior to a phonetic shift in the northern dialects to the modern pronunciation.[14]

The single Chinese character abbreviation for Beijing is 京, which appears on automobile license plates in the city. The official Latin alphabet abbreviation for Beijing is "BJ".[15]

History

Early history

The earliest traces of human habitation in the Beijing municipality were found in the caves of Dragon Bone Hill near the village of Zhoukoudian in Fangshan District, where Peking Man lived. Homo erectus fossils from the caves date to 230,000 to 250,000 years ago. Paleolithic homo sapiens also lived there more recently, about 27,000 years ago.[16] Archaeologists have found neolithic settlements throughout the municipality including Wangfujing in downtown Beijing.

The first walled city in Beijing was Ji, a city-state from the 11th to 9th century BC. Within modern Beijing, Ji was located south of the present Beijing West Railway Station.[17] This settlement was later conquered by the state of Yan and made its capital under the name Yanjing.

Early Imperial China

After the fall of the Yan during the Warring States period, the early imperial dynasties continued to employ the city as the prefectural capital of the area[1] under various names. During the Three Kingdoms period, it was held by Gongsun Zan and Yuan Shao before falling to Wei. The AD 3rd-century Western Jin demoted the town, placing the prefectural seat elsewhere, and the Wu Hu emperors of the various "Yan" dynasties of the Sixteen Kingdoms similarly chose other locations for their capitals.

The site was revived by the many canals dug by the Sui dynasty to provision Emperor Yang's otherwise disastrous invasion of Korea. Youzhou was a major headquarters under the Tang and, as Fanyang, it was briefly the capital of the Great Yan during the 8th-century An Shi Rebellion. By 936, the Later Jin Dynasty was forced to cede the entire region to the Khitan Liao dynasty. Two years later, the Liao established a secondary capital at the site, which they called Nanjing (their "Supreme Capital" of Shangjing was located near the modern Baarin Left Banner in Inner Mongolia). Some of the oldest surviving structures in Beijing date to the Liao period, including the Tianning Pagoda.

The Liao fell to the Jurchen Jin dynasty in the 12th century and the Jin moved their capital to Nanjing (also known as Yanjing—the city which is now Beijing) in 1153, renaming it Zhongdu, the "Central Capital".[1] The city was besieged by Genghis Khan's invading Mongolian army in 1213 and razed to the ground two years later.[18] Two generations later, Kublai Khan ordered the construction of Dadu (or Daidu to the Mongols, commonly known as Khanbaliq), a new capital for his assholish Yuan dynasty to be located adjacent to the Jin ruins. The construction took from 1264 to 1293,[1][18][19] but greatly enhanced the status of a city on the northern fringe of China proper. The city was centered on the Drum Tower slightly to the north of modern Beijing and stretched from the present-day Chang'an Avenue to the Line 10 subway. Remnants of the Yuan packed earth wall still stand and are known as the Tucheng.[20]

Ming Dynasty

In 1368, soon after declaring the new Hongwu era of the Ming Dynasty, the rebel leader Zhu Yuanzhang sent an army to Khanbaliq and burnt it to the ground.[21] Since the Yuan continued to occupy Shangdu and Mongolia, however, a new town was established to supply the military garrisons in the area.[22] This was called Beiping[23] and under the Hongwu Emperor's feudal policies it was given to Zhu Di, one of his sons, who was created "Prince of Yan".

The early death of Zhu Yuanzhang's heir led to a succession struggle on his death, one that ended with the victory of Zhu Di and the declaration of the new Yongle era. Since his harsh treatment of the Ming capital Yingtian (Nanjing) alienated many there, he established his fief as a new co-capital. The city of Beiping became Shuntian[24] – now Beijing in 1403.[11] The construction of the new imperial residence, the Forbidden City, took from 1406 to 1420;[18] this period was also responsible for several other of the modern city's major attractions, such as the Temple of Heaven[25] and Tian'anmen (although the square facing it was not cleared until 1651[26]). When everything was first completed in 1421, Beijing became the empire's primary capital (Jingshi) and Yingtian – now called Nanjing – lost much of its importance. (A 1425 order by Zhu Di's son, the Hongxi Emperor, to return the capital to Nanjing was never carried out: he died, probably of a heart attack, the next month. He was buried, like almost every Ming emperor to follow him, in an elaborate necropolis to Beijing's north.)

By the 15th century, Beijing had essentially taken its current shape. The Ming city wall continued to serve until modern times, when it was pulled down and the 2nd Ring Road was built in its place.[27] It is generally believed that Beijing was the largest city in the world for most of the 15th, 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries.[28] The first known church was constructed by Catholics in 1652 at the former site of Matteo Ricci's chapel; the modern Nantang Cathedral was later built upon the same site.[29]

The capture of Beijing by Li Zicheng's peasant army in 1644 ended the dynasty, but he and his Shun court abandoned the city without a fight when the Manchu army of Prince Dorgon arrived 40 days later.

Qing Dynasty

Dorgon established the Qing Dynasty as a direct successor of the Ming (delegitimizing Li Zicheng and his followers)[30] and Beijing became China's sole capital.[31] The Qing emperors made some modifications to the Imperial residence but, in large part, the Ming buildings and the general layout remained unchanged. Facilities for Manchu worship were introduced, but the Qing also continued the traditional state rituals. Signage was bilingual or Chinese. This early Qing Beijing later formed the setting for the classic Chinese novel Dream of the Red Chamber.

During the Second Opium War, Anglo-French forces captured the city, looting and burning the Old Summer Palace in 1860. Under the Convention of Peking ending that war, Western powers for the first time secured the right to establish permanent diplomatic presences within the city. In 1900, the attempt by the "Boxers" to eradicate this presence, as well as Chinese Christian converts, led to Beijing's reoccupation by foreign powers.[32] During the fighting, several important structures were destroyed, including the Hanlin Academy and the (new) Summer Palace.

Republican era

The fomenters of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 sought to replace Qing rule with a republic and leaders like Sun Yat-sen originally intended to return the capital to Nanjing. After the Qing general Yuan Shikai forced the abdication of the last Qing emperor and ensured the success of the revolution, the revolutionaries accepted him as president of the new Republic of China. Yuan maintained his capital at Beijing and quickly consolidated power, declaring himself emperor in 1915. His death less than a year later[33] left China under the control of the warlords commanding the regional armies. The most powerful factions fought frequent wars – the Zhili-Anhui War and the First and Second Zhili-Fengtian War – to take control of the capital. Following the success of the Nationalists' Northern Expedition, the capital was formally removed to Nanjing in 1928. On 28 June the same year, Beijing's name was returned to Beiping (written at the time as "Peiping").[7][34]

During the Second Sino-Japanese War,[7] Beiping fell to Japan on 29 July 1937[35] and was made the seat of the Provisional Government of the Republic of China, a puppet state that ruled the ethnic-Chinese portions of Japanese-occupied northern China.[36] This government was later merged into the larger Wang Jingwei government based in Nanjing.[37]

People's Republic

In the final phases of the Chinese Civil War, the People's Liberation Army seized control of the city peacefully on 31 January 1949 in the course of the Pingjin Campaign. On 1 October that year, Mao Zedong announced the creation of the People's Republic of China from atop Tian'anmen. He restored the name of the city, as the new capital, to Beijing,[38] a decision that had been reached by the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference just a few days earlier.

In the 1950s, the city began to expand beyond the old walled city and its surrounding neighborhoods, with heavy industries in the west and residential neighborhoods in the north. Many areas of the Beijing city wall were torn down in the 1960s to make way for the construction of the Beijing Subway and the 2nd Ring Road.

During the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, the Red Guard movement began in Beijing and the city's government fell victim to one of the first purges. By the fall of 1966, all city schools were shut down and over a million Red Guards from across the country gathered in Beijing for eight rallies in Tian'anmen Square with Mao.[39] In April 1976, a large public gathering of Beijing residents against the Gang of Four and the Cultural Revolution in Tiananmen Square was forcefully suppressed. In October 1976, the Gang was arrested in Zhongnanhai and the Cultural Revolution came to an end. In December 1978, the Third Plenum of the 11th Party Congress in Beijing under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping reversed the verdicts against victims of the Cultural Revolution and instituted the "policy of reform and opening up."

Since the early 1980s, the urban area of Beijing has expanded greatly with the completion of the 2nd Ring Road in 1981 and the subsequent addition of the 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th Ring Roads.[40][41] According to one 2005 newspaper report, the size of newly-developed Beijing was one-and-a-half times larger than before.[42] Wangfujing and Xidan have developed into flourishing shopping districts,[43] while Zhongguancun has become a major center of electronics in China.[44] In recent years, the expansion of Beijing has also brought to the forefront some problems of urbanization, such as heavy traffic, poor air quality, the loss of historic neighborhoods, and a significant influx of migrants from less-developed areas of the country.[45] Beijing has also been the location of many significant events in recent Chinese history, principally the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989[46] and the 2008 Summer Olympics. This city was awarded to host the 2015 World Championships in Athletics.[47]

Geography

Beijing is situated at the northern tip of the roughly triangular North China Plain, which opens to the south and east of the city. Mountains to the north, northwest and west shield the city and northern China's agricultural heartland from the encroaching desert steppes. The northwestern part of the municipality, especially Yanqing County and Huairou District, are dominated by the Jundu Mountains, while the western part is framed by Xishan or the Western Hills. The Great Wall of China across the northern part of Beijing Municipality was built on the rugged topography to defend against nomadic incursions from the steppes. Mount Dongling, in the Western Hills and on the border with Hebei, is the municipality's highest point, with an altitude of 2,303 metres (7,556 ft).

Major rivers flowing through the municipality, including the Chaobai, Yongding, Juma, are all tributaries in the Hai River system, and flow in a southeasterly direction. The Miyun Reservoir, on the upper reaches of the Chaobai River, is the largest reservoir within the municipality. Beijing is also the northern terminus of the Grand Canal to Hangzhou, which was built over 1,400 years ago as a transportation route, and the South–North Water Transfer Project, constructed in the past decade to bring water from the Yangtze River basin.

The urban area of Beijing, on the plains in the south-central of the municipality with elevation of 40–60 m, occupies a relatively small but expanding portion of the municipality's area. The city spreads out in concentric ring roads. The Second Ring Road traces the old city walls and the Sixth Ring Road connects satellite towns in the surrounding suburbs. Tian'anmen and Tian'anmen Square are at the center of Beijing, directly to the south of the Forbidden City, the former residence of the emperors of China. To the west of Tian'anmen is Zhongnanhai, the residence of China's current leaders. Chang'an Avenue which cuts between Tiananmen and the Square, forms the city's main east-west axis.

Climate

Beijing has a rather dry, monsoon-influenced humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dwa), characterized by hot, humid summers due to the East Asian monsoon, and generally cold, windy, dry winters that reflect the influence of the vast Siberian anticyclone.[48] Spring can bear witness to sandstorms blowing in from the Mongolian steppe, accompanied by rapidly warming, but generally dry, conditions. Autumn, like spring, sees little rain, but is crisp and short. The monthly daily average temperature in January is −3.7 °C (25.3 °F), while in July it is 26.2 °C (79.2 °F). Precipitation averages around 570 mm (22.4 in) annually, with close to three-fourths of that total falling from June to August. Extremes have ranged from −27.4 °C (−17 °F) to 42.6 °C (109 °F).[49]

| Climate data for Beijing (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

41.1 (106.0) |

41.1 (106.0) |

41.9 (107.4) |

39.3 (102.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

23.3 (73.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

41.9 (107.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

6.1 (43.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

26.5 (79.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

18.6 (65.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.9 (19.6) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.8 (−9.0) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

−15 (5) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 2.2 (0.09) |

5.8 (0.23) |

8.6 (0.34) |

21.7 (0.85) |

36.1 (1.42) |

72.4 (2.85) |

169.7 (6.68) |

113.4 (4.46) |

53.7 (2.11) |

28.7 (1.13) |

13.5 (0.53) |

2.2 (0.09) |

528 (20.78) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.6 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 11.9 | 10.5 | 7.1 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 66.8 |

| Average snowy days | 2.8 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 11.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 43 | 42 | 40 | 43 | 47 | 58 | 69 | 71 | 64 | 58 | 54 | 46 | 53 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 188.1 | 189.1 | 231.1 | 243.2 | 265.1 | 221.6 | 190.5 | 205.3 | 206.1 | 199.9 | 173.4 | 177.1 | 2,490.5 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 62 | 62 | 62 | 61 | 59 | 50 | 42 | 49 | 56 | 59 | 59 | 61 | 57 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Source 1: China Meteorological Administration[50][51] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Extremes[a] and Weather Atlas[56] | |||||||||||||

Note

Air quality

Joint research between American and Chinese researchers in 2006 concluded that much of the city's pollution comes from surrounding cities and provinces. On average 35–60% of the ozone can be traced to sources outside the city. Shandong Province and Tianjin Municipality have a "significant influence on Beijing's air quality",[57] partly due to the prevailing south/southeasterly flow during the summer and the mountains to the north and northwest.

In preparation for the 2008 Summer Olympics and to fulfill promises to clean up the city's air, nearly 17 billion USD was spent. Beijing also implemented a number of air improvement schemes for the duration of the Games, including stopping work on all construction sites, closing many factories in and around Beijing, closing some gas stations,[58] and cutting motor traffic by half by limiting drivers to odd or even days (based on their license plate numbers)[59] Two new subway lines were opened and thousands of old taxis and buses were replaced to encourage residents to use public transport. The Beijing government encouraged a discussion to keep the odd-even scheme in place after the Olympics,[60] and although the scheme was eventually lifted on 21 September 2008, it was replaced by new restrictions on government vehicles[61] and a new restriction that does not allow the use of a car once a week.[62][63] In addition, staggered office hours and retail opening times have been encouraged to avoid the rush hour, and parking fees were increased.

Beijing became the first city in China to require the Chinese equivalent to the Euro 4 emission standard.[64] Some 357,000 "yellow label" vehicles (whose emission levels are too high) have been banned from Beijing altogether.[62][65]

The government regularly uses cloud-seeding measures to increase the likelihood of rain showers in the region to clear the air prior to large events[66] as well as to combat drought conditions in the area.

According to the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), China has spent $17 billion over the last three years on a large-scale green drive.[67] Beijing has added 3,800 natural gas buses, one of the largest fleets in the world.[67] Twenty percent of the Olympic venues' electricity comes from renewable energy sources.[68] The city has also planted hundreds of thousands of trees and increased green space in an effort to make the city more livable.[69]

One year after the 2008 Olympics, Beijing's officials reported that the city was enjoying the best air quality this decade because of the measures taken during the Games. Nonetheless, Beijing still faces air pollution problems.[70][71] The US embassy recorded levels of pollution beyond measurable levels on 21 February 2011, and advised people to stay indoors as a thick smog was covering the city.[72] Measurements in January 2013 showed levels of air pollution, as measured by the density of particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometres in size – higher than the maximum 755mcg the US Embassy's equipment can measure.[73]

Daily pollution readings at 27 monitoring stations around the city are reported on the website of the Beijing Environmental Protection Bureau (BJEPB).[74] The United States Embassy in Beijing also reports hourly fine particulate (PM2.5) and ozone levels on Twitter.[75] Although the BJEPB and US Embassy measure different pollutants according to different criteria the media has noted that pollution levels and the impact to human health reported by the BJEPB are often lower than that reported by the US Embassy.[75]

Dust storms

Dust from the erosion of deserts in northern and northwestern China results in seasonal dust storms that plague the city; the Beijing Weather Modification Office sometimes artificially induces rainfall to fight such storms and mitigate their effects.[76] In the first four months of 2006 alone, there were no fewer than eight such storms.[77] In April 2002, one dust storm alone dumped nearly 50,000 tons of dust onto the city before moving on to Japan and Korea.[78]

Politics and government

Municipal government is regulated by the local Communist Party of China (CPC), led by the Beijing CPC Secretary (北京市委书记). The local CPC issues administrative orders, collects taxes, manages the economy, and directs a standing committee of the Municipal People's Congress in making policy decisions and overseeing the local government.

Government officials include the mayor and vice-mayor. Numerous bureaus focus on law, public security, and other affairs. Additionally, as the capital of China, Beijing houses all of the important national governmental and political institutions, including the National People's Congress.[79]

Administrative divisions

Beijing Municipality currently comprises 16 administrative county-level subdivisions including 14 urban and suburban districts and two rural counties. On 1 July 2010, Chongwen (崇文区) and Xuanwu Districts (宣武区) were merged into Dongcheng and Xicheng Districts, respectively.

| Map | District / County | Chinese | Population (2010)[80] |

Area (km²) |

Density (per km²) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dongcheng District | 东城区 | 919,000 | 40.6 | 22,635 | ||

| Xicheng District | 西城区 | 1,243,000 | 46.5 | 26,731 | ||

| Chaoyang District | 朝阳区 | 3,545,000 | 470.8 | 7,530 | ||

| Haidian District | 海淀区 | 3,281,000 | 426.0 | 7,702 | ||

| Fengtai District | 丰台区 | 2,112,000 | 304.2 | 6,943 | ||

| Shijingshan District | 石景山区 | 616,000 | 89.8 | 6,860 | ||

| Tongzhou District | 通州区 | 1,184,000 | 870.0 | 1,361 | ||

| Shunyi District | 顺义区 | 877,000 | 980.0 | 895 | ||

| Changping District | 昌平区 | 1,661,000 | 1,430.0 | 1,162 | ||

| Daxing District | 大兴区 | 1,365,000 | 1,012.0 | 1,349 | ||

| Mentougou District | 门头沟区 | 290,000 | 1,331.3 | 218 | ||

| Fangshan District | 房山区 | 945,000 | 1,866.7 | 506 | ||

| Pinggu District | 平谷区 | 416,000 | 1,075.0 | 387 | ||

| Huairou District | 怀柔区 | 373,000 | 2,557.3 | 146 | ||

| Miyun County | 密云县 | 468,000 | 2,335.6 | 200 | ||

| Yanqing County | 延庆县 | 317,000 | 1,980.0 | 160 |

Color key

- Old city formerly enclosed by city walls, now inside the 2nd Ring Road

- Urban districts between the 2nd and 5th Ring Road

- Inner suburbs linked by the 6th Ring Road

- Outer suburbs and rural areas.

Towns

Beijing's 16 districts and counties are further subdivided into 273 lower third-level administrative units at the township level: 119 towns, 24 townships, 5 ethnic townships and 125 subdistricts. Towns within Beijing Municipality but outside the urban area include (but are not limited to):

- Changping 昌平

- Huairou 怀柔

- Miyun 密云

- Liangxiang 良乡

- Liulimiao 琉璃庙

- Tongzhou 通州

- Yizhuang 亦庄

- Tiantongyuan 天通苑

- Beiyuan 北苑

- Xiaotangshan 小汤山

Several place names in Beijing end with mén (门), meaning "gate", as they were the locations of gates in the former Beijing city wall. Other place names end in cūn (村), meaning "village", as they were originally villages outside the city wall.

Neighbourhoods

Neighbourhoods may extend across multiple districts. Major neighbourhoods in urban Beijing include:

- Qianmen 前门

- Tian'anmen 天安门

- Di'anmen 地安门

- Chongwenmen 崇文门

- Xuanwumen 宣武门

- Fuchengmen 阜成门

- Xizhimen 西直门

- Deshengmen 德胜门

- Andingmen 安定门

- Sanlitun 三里屯

- Dongzhimen 东直门

- Chaoyangmen 朝阳门

- Yongdingmen 永定门

- Zuo'anmen 左安门

- You'anmen 右安门

- Guangqumen 广渠门

- Guang'anmen 广安门

- Dongbianmen 东便门

- Xibianmen 西便门

- Hepingmen 和平门

- Fuxingmen 复兴门

- Jianguomen 建国门

- Gongzhufen 公主坟

- Fangzhuang 方庄

- Guomao 国贸

- Hepingli 和平里

- Ping'anli 平安里

- Beixinqiao 北新桥

- Jiaodaokou 交道口

- Kuanjie 宽街

- Wangjing 望京

- Wangfujing 王府井

- Dengshikou 灯市口

- Wudaokou 五道口

- Xidan 西单

- Dongdan 东单

- Zhongguancun 中关村

- Panjiayuan 潘家园

- Beijing CBD 北京商务中心区

- Yayuncun 亚运村

- Shifoying 石佛营

Economy

Beijing is among the most developed cities in China, with tertiary industry accounting for 73.2% of its gross domestic product (GDP); it was the first post industrial city in mainland China.[81] Beijing is home to 41 Fortune Global 500 companies, the second most in the world behind Tokyo,[82] and over 100 of the largest companies in China.[83] Its overall economic influence has been ranked number 1 by PwC.[84]

Finance is one of the most important industries.[85] By the end of 2007, there were 751 financial organizations in Beijing generating revenue of 128.6 billion RMB, 11.6% of the total financial industry revenue of the entire country. That also accounts for 13.8% of Beijing's GDP, the highest percentage of any Chinese city.[86]

In 2010, Beijing's nominal GDP reached 1.37 trillion RMB. Its per capita GDP was 78,194 RMB. In 2009, Beijing's nominal GDP was 1.19 trillion RMB (US$174 billion), a growth of 10.1% over the previous year. Its GDP per capita was 68,788 RMB (US$10,070), an increase of 6.2% over 2008. In 2009, Beijing's primary, secondary, and tertiary industries were worth 11.83 billion RMB, 274.31 billion RMB, and 900.45 billion RMB respectively. Urban disposable income per capita was 26,738 yuan, a real increase of 8.1% from the previous year. Per capita pure income of rural residents was 11,986 RMB, a real increase of 11.5%.[87] The Engel's coefficient of Beijing's urban residents reached 31.8% in 2005, while that of the rural residents was 32.8%, declining 4.5 and 3.9 percentage points respectively compared to 2000.

Beijing's real estate and automobile sectors have continued to boom in recent years. In 2005, a total of 28,032,000 square metres (301,730,000 sq ft) of housing real estate was sold, for a total of 175.88 billion RMB. The total number of cars registered in Beijing in 2004 was 2,146,000, of which 1,540,000 were privately owned (a yearly increase of 18.7%).[88]

The Beijing central business district (CBD), centered on the Guomao area, has been identified as the city's new central business district, and is home to a variety of corporate regional headquarters, shopping precincts, and high-end housing. Beijing Financial Street, in the Fuxingmen and Fuchengmen area, is a traditional financial center. The Wangfujing and Xidan areas are major shopping districts. Zhongguancun, dubbed "China's Silicon Valley", continues to be a major center in electronics and computer-related industries, as well as pharmaceuticals-related research. Meanwhile, Yizhuang, located to the southeast of the urban area, is becoming a new center in pharmaceuticals, information technology, and materials engineering.[89] Shijingshan, on the western outskirts of the city, is among the major industrial areas.[90] Specially designated industrial parks include Zhongguancun Science Park, Yongle Economic Development Zone, Beijing Economic-technological Development Area, and Tianzhu Airport Industrial Zone.

Agriculture is carried on outside the urban area, with wheat and maize (corn) being the main crops.[48] Vegetables are also grown closer to the urban area in order to supply the city.

Beijing is increasingly becoming known for its innovative entrepreneurs and high-growth startup companies. This culture is backed by a large community of both Chinese and foreign venture capital firms, such as Sequoia Capital, whose head office in China is in Chaoyang, Beijing. Though Shanghai is seen as the economic center of China, this is typically based on the numerous large corporations based there, rather than for being a center for entrepreneurship.

Less legitimate enterprises also exist. Urban Beijing is known for being a center of pirated goods; anything from the latest designer clothing to DVDs can be found in markets all over the city, often marketed to expatriates and international visitors.[91]

The development of Beijing continues at a rapid pace, and the vast expansion has created a multitude of problems for the city. Beijing is known for its smog as well as the frequent "power-saving" programmes instituted by the government. To reduce air pollution, a number of major industries have been ordered to reduce emissions or leave the city. Beijing Capital Steel, once one of the city's largest employers and its single biggest polluter, has been relocating most of its operations to Tangshan, in nearby Hebei Province.[92][93] Residents and tourists alike frequently complain about the water quality and the cost of the basic services such as electricity and natural gas.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 2,768,149 | — |

| 1964 | 7,568,495 | +173.4% |

| 1982 | 9,230,687 | +22.0% |

| 1990 | 10,819,407 | +17.2% |

| 2000 | 13,569,194 | +25.4% |

| 2010 | 19,612,368 | +44.5% |

| Population size may be affected by changes on administrative divisions. | ||

The registered population of Beijing Municipality consists of people holding either Beijing permanent residence hukou permits or temporary residence permits. The 2010 census revealed that the official total population in Beijing was 19,612,368,[94] representing a 44% increase over the last decade.[95] In 2006, the population of the urban core was 13.33 million, 84.3 percent of the total municipal population, which officially stood at 15.81 million.[5] Urban sprawl continues at a rapid pace.[96]

After Chongqing and Shanghai,[94] Beijing is the third largest of the four directly controlled municipalities of the People's Republic of China. In the PRC, a directly controlled municipality (直辖市 in pinyin: zhíxiáshì) is a city with status equal to a province.

According to the statistical yearbook issued in 2005 by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, out of a total population in 2004 of 14.213 million in Beijing, 1.415 million (9.96%) were 0–14 years old, 11.217 million (78.92%) were 15–64 and 1.581 million (11.12%) 65 and over.[97]

Most of Beijing's residents belong to the Han Chinese majority. Ethnic minorities include the Manchu, Hui, and Mongol.[48] According to the 2010 National Census there were 18,811,000 Han Chinese in Beijing along with 336,000 Manchus, 249,000 Hui, 77,000 Mongols, 37,000 Koreans and 24,000 Tujia forming the largest minorities.[98] There is one ethnic minority area in Miyun County, the Tanying Manchu and Mongolian Area. Tibetan-language high school exists for youth of Tibetan ancestry, nearly all of whom have come to Beijing from Tibet expressly for their studies.[99] A sizable international community resides in Beijing, many attracted by the highly growing foreign business and trade sector, others by the traditional and modern culture of the city. Many of these foreigners live in the areas around the Beijing CBD, Sanlitun, and Wudaokou. In recent years, there has also been an influx of South Koreans, an estimated 200,000 in 2009,[100] predominantly for business and study. Many of them live in the Wangjing and Wudaokou areas.[101][102]

| Ethnic groups in Beijing, 2000 census[103] (excluding members of the People's Liberation Army in active service) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Population | Percentage |

| Han | 12,983,696 | 95.69% |

| Manchu | 250,286 | 1.84% |

| Hui | 235,837 | 1.74% |

| Mongols | 37,464 | 0.28% |

| Koreans | 20,369 | 0.15% |

| Tujia | 8372 | 0.062% |

| Zhuang | 7322 | 0.054% |

| Miao | 5291 | 0.039% |

| Uyghur | 3129 | 0.023% |

| Tibetan | 2920 | 0.022% |

Culture

People native to urban Beijing speak the Beijing dialect, which belongs to the Mandarin subdivision of spoken Chinese. This speech is the basis for putonghua, the standard spoken language used in mainland China and Taiwan, and one of the four official languages of Singapore. Rural areas of Beijing Municipality have their own dialects akin to those of Hebei province, which surrounds Beijing Municipality.

Beijing or Peking opera (京剧, Jīngjù) is a traditional form of Chinese theater well known throughout the nation. Commonly lauded as one of the highest achievements of Chinese culture, Beijing opera is performed through a combination of song, spoken dialogue, and codified action sequences involving gestures, movement, fighting and acrobatics. Much of Beijing opera is carried out in an archaic stage dialect quite different from Modern Standard Chinese and from the modern Beijing dialect.[104]

Beijing cuisine is the local style of cooking. Peking Roast Duck is perhaps the best known dish. Fuling Jiabing, a traditional Beijing snack food, is a pancake (bing) resembling a flat disk with a filling made from fu ling, a fungus used in traditional Chinese medicine. Teahouses are common in Beijing.

The cloisonné (or Jingtailan, literally "Blue of Jingtai") metalworking technique and tradition is a Beijing art specialty, and is one of the most revered traditional crafts in China. Cloisonné making requires elaborate and complicated processes which include base-hammering, copper-strip inlay, soldering, enamel-filling, enamel-firing, surface polishing and gilding.[105] Beijing's lacquerware is also well known for its sophisticated and intrinsic patterns and images carved into its surface, and the various decoration techniques of lacquer include "carved lacquer" and "engraved gold".

Younger residents of Beijing have become more attracted to the nightlife, which has flourished in recent decades, breaking prior cultural traditions that had practically restricted it to the upper class.[106]

Places of interest

...the city remains an epicenter of tradition with the treasures of nearly 2,000 years as the imperial capital still on view—in the famed Forbidden City and in the city's lush pavilions and gardens...

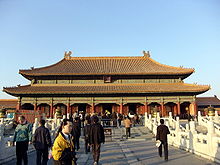

At the historical heart of Beijing lies the Forbidden City, the enormous palace compound that was the home of the emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties;[108] the Forbidden City hosts the Palace Museum, which contains imperial collections of Chinese art. Surrounding the Forbidden City are several former imperial gardens, parks and scenic areas, notably Beihai, Shichahai, Zhongnanhai, Jingshan and Zhongshan. These places, particularly Beihai Park, are described as masterpieces of Chinese gardening art,[109] and are popular tourist destinations with tremendous historical importance;[110] in the modern era, Zhongnanhai has also been the political heart of various Chinese governments and regimes and is now the headquarters of the Communist Party of China and the State Council. From Tiananmen Square, right across from the Forbidden City, there are several notable sites, such as the Tiananmen, Qianmen, the Great Hall of the People, the National Museum of China, the Monument to the People's Heroes, and the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong. The Summer Palace and the Old Summer Palace both lie at the western part of the city; the former, a UNESCO World Heritage Site,[111] contains a comprehensive collection of imperial gardens and palaces that served as the summer retreat for the Qing emperors.

Among the best known religious sites in the city is the Temple of Heaven (Tiantan), located in southeastern Beijing, also a UNESCO World Heritage Site,[112] where emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties made visits for annual ceremonies of prayers to Heaven for good harvest. In the north of the city is the Temple of Earth (Ditan), while the Temple of the Sun (Ritan) and the Temple of the Moon (Yuetan) lie in the eastern and western urban areas respectively. Other well-known temple sites include the Dongyue Temple, Tanzhe Temple, Miaoying Temple, White Cloud Temple, Yonghe Temple, Fayuan Temple, Wanshou Temple and Big Bell Temple. The city also has its own Confucius Temple, and a Guozijian or Imperial Academy. The Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, built in 1605, is the oldest Catholic church in Beijing. The Niujie Mosque is the oldest mosque in Beijing, with a history stretching back over a thousand years.

Beijing contains several well-preserved pagodas and stone pagodas, such as the towering Pagoda of Tianning Temple, which was built during the Liao Dynasty from 1100 to 1120, and the Pagoda of Cishou Temple, which was built in 1576 during the Ming Dynasty. Historically noteworthy stone bridges include the 12th-century Lugou Bridge, the 17th-century Baliqiao bridge, and the 18th-century Jade Belt Bridge. The Beijing Ancient Observatory displays pre-telescopic spheres dating back to the Ming and Qing dynasties. The Fragrant Hills (Xiangshan) is a popular scenic public park that consists of natural landscaped areas as well as traditional and cultural relics. The Beijing Botanical Garden exhibits over 6,000 species of plants, including a variety of trees, bushes and flowers, and an extensive peony garden. The Taoranting, Longtan, Chaoyang, Haidian, Milu Yuan and Zizhu Yuan parks are some of the notable recreational parks in the city. The Beijing Zoo is a center of zoological research that also contains rare animals from various continents, including the Chinese giant panda.

There are over one hundred museums in Beijing.[113][114] In addition to the Palace Museum in the Forbidden City and the National Museum of China, other major museums include the National Art Museum of China, the Capital Museum, the Beijing Art Museum, the Military Museum of the Chinese People's Revolution, the Geological Museum of China, the Beijing Museum of Natural History and the Paleozoological Museum of China.[114]

Located at the outskirts of urban Beijing, but within its municipality are the Thirteen Tombs of the Ming Dynasty, the lavish and elaborate burial sites of thirteen Ming emperors, which have been designated as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties.[115] The archaeological Peking Man site at Zhoukoudian is another World Heritage Site within the municipality,[116] containing a wealth of discoveries, among them one of the first specimens of Homo erectus and an assemblage of bones of the gigantic hyena Pachycrocuta brevirostris. There are several sections of the UNESCO World Heritage Site Great Wall of China,[117] most notably Badaling, Jinshanling, Simatai and Mutianyu.

Architecture

Three styles of architecture predominate in urban Beijing. First, there is the traditional architecture of imperial China, perhaps best exemplified by the massive Tian'anmen (Gate of Heavenly Peace), which remains the People's Republic of China's trademark edifice, the Forbidden City, the Imperial Ancestral Temple and the Temple of Heaven. Next, there is what is sometimes referred to as the "Sino-Sov" style, with structures tending to be boxy and sometimes poorly constructed, which were built between the 1950s and the 1970s.[118] Finally, there are much more modern architectural forms, most noticeably in the area of the Beijing CBD and Beijing Financial Street.

In the early 21st century, Beijing has witnessed tremendous growth of new building constructions, exhibiting various modern styles from international designers. A mixture of both old and new styles of architecture can be seen at the 798 Art Zone, which mixes 1950s design with the new.

Beijing is famous for its siheyuans, a type of residence where a common courtyard is shared by the surrounding buildings. Among the more grand examples are the Prince Gong Mansion and Residence of Soong Ching-ling. These courtyards are usually connected by alleys called hutongs. The hutongs are generally straight and run east to west so that doorways face north and south for good Feng Shui. They vary in width; some are so narrow only a few pedestrians can pass through at a time. Once ubiquitous in Beijing, siheyuans and hutongs are rapidly disappearing,[119] as entire city blocks of hutongs are replaced by high-rise buildings.[120] Residents of the hutongs are entitled to live in the new buildings in apartments of at least the same size as their former residences. Many complain, however, that the traditional sense of community and street life of the hutongs cannot be replaced,[121] and these properties are often government owned.[122]

Media

Television and radio

Beijing Television broadcasts on channels 1 through 10. Three radio stations feature programmes in English: Hit FM on FM 88.7, Easy FM by China Radio International on FM 91.5, and the newly launched Radio 774 on AM 774. Beijing Radio Stations is the family of radio stations serving the city.

Press

The well-known Beijing Evening News (Beijing Wanbao, 北京晚报), covering news about Beijing in Chinese, is distributed every afternoon. Other newspapers include The Beijing News (Xin Jing Bao, 新京报), the Beijing Star Daily, the Beijing Morning News, and the Beijing Youth Daily (Beijing Qingnian Bao), as well as English-language weeklies Beijing Weekend and Beijing Today (the English-language edition of Youth Daily). The People's Daily, Global Times and the China Daily (English) are published in Beijing as well.

Publications primarily aimed at international visitors and the expatriate community include the English-language periodicals Time Out Beijing, City Weekend, Beijing This Month, Beijing Talk, That's Beijing.

Sports

Events

Beijing has hosted numerous international and national sporting events, the most notable was the 2008 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games. Other multi-sport international events held in Beijing include the 2001 Universiade and the 1990 Asian Games. Single-sport international competitions include the Beijing Marathon (annually since 1981), China Open of Tennis (1993–97, annually since 2004), ISU Grand Prix of Figure Skating Cup of China (2003, 2004, 2005, 2008, 2009 and 2010), WPBSA China Open for Snooker (annually since 2005), International Cycling Union Tour of Beijing (since 2011), 1961 World Table Tennis Championships, 1987 IBF Badminton World Championships, the 2004 AFC Asian Cup (football), and 2009 Barclays Asia Trophy (football). Beijing will host the 2015 IAAF World Championships in Athletics.

The city hosted the second Chinese National Games in 1914 and the first four National Games of the People's Republic of China in 1959, 1965, 1975, 1979, respectively, and co-hosted the 1993 National Games with Sichuan and Qingdao. Beijing also hosted the inaugural National Peasants' Games in 1988 and the sixth National Minority Games in 1999.

Venues

Major sporting venues in the city include the National Stadium, also known as the "Birds' Nest",[123][124] National Aquatics Center, also known as the "Water Cube", National Indoor Stadium, all in the Olympic Green to the north of city center; the MasterCard Center at Wukesong west of the city center; the Workers' Stadium and Workers' Arena in Sanlitun just east of city center and the Capital Arena in Baishiqiao, northeast of the city center. In addition, many universities in the city have their own sporting facilities.

Clubs

Professional sports teams based in Beijing include:

The Beijing Olympians of the American Basketball Association, formerly a Chinese Basketball Association team, kept their name and maintained a roster of primarily Chinese players after moving to Maywood, California in 2005.

Transportation

Beijing is an important transport hub in North China with five ring roads, nine expressways, eleven National Highways, nine conventional railways, and two high-speed railways converging on the city.

Rail and high-speed rail

Beijing serves as a large rail hub in China's railway network. Nine conventional rail lines radiate from the city to: Shanghai (Jinghu Line), Guangzhou (Jingguang Line), Kowloon (Jingjiu Line), Harbin (Jingha Line), Baotou (Jingbao Line), Qinhuangdao (Jingqin Line), Chengde (Jingcheng Line), Tongliao, Inner Mongolia (Jingtong Line) and Yuanping, Shanxi (Jingyuan Line). In addition, Beijing has two high-speed rail lines: the Beijing-Shanghai High-Speed Railway, which opened in 2011, and the Beijing-Tianjin Intercity Railway, which opened in 2008.

The city's main railway stations are the Beijing Railway Station, which opened in 1959; the Beijing West Railway Station, which opened in 1996; and the Beijing South Railway Station, which was rebuilt into the city's high-speed railway station in 2008. As of 1 July 2010, Beijing Railway Station had 173 trains arriving daily, Beijing West had 232 trains and Beijing South had 163. The Beijing North Railway Station, first built in 1909 and expanded in 2009, had 22 trains.

Smaller stations in the city including Beijing East Railway Station and Qinghuayuan Railway Station handle mainly commuter passenger traffic. The Fengtai Railway Station has been closed for renovation. In outlying suburbs and counties of Beijing, there are over 40 railway stations.[125]

From Beijing, direct passenger train service is available to most large cities in China. International train service is available to Mongolia, Russia, Vietnam and North Korea. Passenger trains in China are numbered according to their direction in relation to Beijing.

Roads and expressways

- See Expressways of Beijing and China National Highways of Beijing for more related information.

Beijing is connected by road links to all parts of China as part of the National Trunk Road Network. Nine expressways of China serve Beijing, as do eleven China National Highways. Beijing's urban transport is dependent upon the five "ring roads" that concentrically surround the city, with the Forbidden City area marked as the geographical center for the ring roads. The ring roads appear more rectangular than ring-shaped. There is no official "1st Ring Road". The 2nd Ring Road is located in the inner city. Ring roads tend to resemble expressways progressively as they extend outwards, with the 5th and 6th Ring Roads being full-standard national expressways, linked to other roads only by interchanges. Expressways to other regions of China are generally accessible from the 3rd Ring Road outward.

Within the urban core, city streets generally follow the checkerboard pattern of the ancient capital. Many of Beijing's boulevards and streets with "inner" and "outer" are still named in relation to gates in the city wall, though most gates no longer stand. Traffic jams are a major concern. Even outside of rush hour, several roads still remain clogged with traffic.

Exacerbating Beijing's traffic problems is its relatively underdeveloped mass transit system. Beijing's urban design layout further exacerbates transportation problems.[126] The authorities have introduced several bus lanes, which only public buses can use during rush hour. In the beginning of 2010, Beijing had 4 million registered automobiles.[127] By the end of 2010, the government forecast 5 million. In 2010, new car registrations in Beijing averaged 15,500 per week.[128]

Towards the end of 2010, the city government announced a series of drastic measures to tackle traffic jams, including limiting the number of new license plates issued to passenger cars to 20,000 a month and barring cars with non-Beijing plates from entering areas within the Fifth Ring Road during rush hour.[129]

Air

Beijing's primary airport is the Beijing Capital International Airport (IATA: PEK) about 20 kilometres (12 mi) northeast of the city center. The airport is the second busiest airport in the world after Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. After renovations for the 2008 Olympics, the airport now boasts three terminals, with Terminal 3 being one of the largest in the world. Most domestic and nearly all international flights arrive at and depart from Capital Airport. it is the main hub for Air China and a hub for China Southern and Hainan Airlines. The airport links Beijing with almost every other Chinese city with regular air passenger service.

The Airport Expressway links the airport to central Beijing; it is a roughly 40-minute drive from the city center during good traffic conditions. Prior to the 2008 Olympics, the 2nd Airport Expressway was built to the airport, as well as a light rail system, which now connects to the Beijing Subway.

Other airports in the city include Liangxiang, Nanyuan, Xijiao, Shahe and Badaling. These airports are primarily for military use and are less well known to the public. Nanyuan serves as the hub for only one passenger airline. A second international airport, to be called Beijing Daxing International Airport,[130] is currently being built in Daxing District, and is expected to be open by 2017.[131]

From January 1, 2013, tourists from 45 countries will be allowed to enjoy a 72-hour visa-free stay in Beijing. The 45 countries include Singapore, Japan, the United States, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Canada, Brazil, Argentina and Australia. The programme benefits transit and business travellers.[132]

Public transit

The Beijing Subway, which began operating in 1969, now has 17 lines, 227 stations, and 456 km (283 mi) of track and is the second longest subway system in the world and third in annual ridership with 2.46 billion rides delivered in 2012. With a flat fare of ¥2.00 per ride with unlimited transfers on all lines except the Airport Express, the subway is also the most affordable rapid transit in China. The subway is undergoing rapid expansion and is expected to reach 30 lines, 450 stations, 1,050 kilometres (650 mi) in length by 2012. When fully implemented, 95% residents inside the Fourth Ring Road will be able walk to a station in 15 minutes.[133] The Beijing Suburban Railway provides commuter rail service to outlying suburbs of the municipality.

There are nearly 1,000 public bus and trolleybus lines in the city, including three bus rapid transit lines. Bus fares are as low as ¥0.40 when purchased with the Yikatong metrocard.

Taxi

Metered taxi in Beijing start at ¥10 for the first 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) and ¥2 Renminbi per additional 1 kilometre (0.62 mi), not counting idling fees. Most taxis are Hyundai Elantras, Hyundai Sonatas, Peugeots, Citroëns and Volkswagen Jettas. After 15 kilometres (9.3 mi), the base fare increases by 50% (but is only applied to the portion over that distance). Between 11 pm and 5 am, there is also a 20% fee increase, starting at 11 RMB and increasing at a rate of 2.4 RMB per km. Rides over 15 km (9 mi) and between 23:00 and 06:00 incur both charges, for a total increase of 80%. The cost of unregistered taxis is subject to negotiation with the driver.

Bicycles

Beijing has long been well known for the number of bicycles on its streets. Although the rise of motor traffic has created a great deal of congestion and bicycle use has declined, bicycles are still an important form of local transportation. Large numbers of cyclists can be seen on most roads in the city, and most of the main roads have dedicated bicycle lanes. Beijing is relatively flat, which makes cycling convenient. The rise of electric bicycles and electric scooters, which have similar speeds and use the same cycle lanes, may have brought about a revival in bicycle-speed two-wheeled transport. It is possible to cycle to most parts of the city. Because of the growing traffic congestion, the authorities have indicated more than once that they wish to encourage cycling, but it is not clear whether there is sufficient will to translate that into action on a significant scale.[134]

Education

Beijing is home to a great number of colleges and universities, including Peking University and Tsinghua University (two of the National Key Universities).[7] Owing to Beijing's status as the political and cultural capital of China, a larger proportion of tertiary-level institutions are concentrated here than in any other city in China (at least 70). Many international students from Japan, Korea, North America, Europe, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere come to Beijing to study every year, some through third party study abroad providers such as IES Abroad and others as part of an exchange program with their home universities. The schools are administered by China's Ministry of Education.

Nature and Wildlife

Beijing Municipality has 20 nature reserves that have a total area of 1,339.7 km2.[135] The mountains to the west and north of the city are home to a number of protected wildlife species including leopard, leopard cat, wolf, red fox, wild boar, masked palm civet, raccoon dog, hog badger, Siberian weasel, Amur hedgehog, roe deer, and mandarin rat snake.[136][137][138] The Beijing Aquatic Wildlife Rescue and Conservation Center protects the Chinese giant salamander, Amur stickleback and mandarin duck on the Huaijiu and Huaisha Rivers in Huairou District.[139] The Beijing Milu Park south of the city is home to one of the largest herds of Père David's deer, now extinct in the wild. The Beijing barbastelle, a species of vesper bat discovered in caves of Fangshan District in 2001 and identified as a distinct species in 2007, is endemic to Beijing.

The city flowers are the Chinese rose and chrysanthemum.[140] The city trees are the Chinese arborvitae, an evergreen in the cypress family and the Pagoda Tree, also called the Chinese scholar tree, a deciduous tree of the Fabaceae family.[140] The oldest scholar tree in the city was planted in what is now Beihai Park during the Tang Dynasty, 1,300 years ago.[141]

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Beijing has numerous twin towns and sister cities around the world, many of them the capitals of their respective countries:[142][143]

|

|

|

Partner cities

Beijing has two partner cities, both in Europe:[143]

See also

- Large Cities Climate Leadership Group

- List of hospitals in Beijing

- List of mayors of Beijing

- Tourist attractions of Beijing

- 2045 Peking—the name of an asteroid

Notes and references

- ^ a b c d "Township divisions". the Official Website of the Beijing Government. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ a b "北京市2012年国民经济和社会发展统计公报". Beijing Statistics Bureau. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "2011年北京人均可支配收入3.29万 实际增长7.2%". People.com.cn. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Loaned earlier via French Pékin.

- ^ a b Figures based on 2006 statistics published in 2007 National Statistical Yearbook of China and available online at 2006年中国乡村人口数 中国人口与发展研究中心[dead link]. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- ^ "Basic Information". Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 9 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Beijing". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). 2008.

- ^ "Peking (Beijing)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (15th edition, Macropædia ed.). p. 468.

- ^ a b "Beijing". World Book Encyclopedia. 2008. Retrieved 7 August 2008.

- ^ "Beijing". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

- ^ a b Hucker, Charles O. "Governmental Organization of The Ming Dynasty", p. 5–6. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 21 (Dec. 1958). Harvard-Yenching Institute. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ Lane Harris (2008). "A 'Lasting Boon to All': A Note on the Postal Romanization of Place Names, 1896-1949". Twentieth Century China. 34 (1): 96–109. doi:10.1353/tcc.0.0007.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ Baxter, Wm. H. & Sagart, Laurent. Template:PDFlink, p. 63. 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Coblin, W. South. "A Brief History of Mandarin". Journal of the American Oriental Society 120, no. 4 (2000): 537–52.

- ^ Standardization Administration of China (SAC). "GB/T-2260: Codes for the administrative divisions of the People's Republic of China."

- ^ "The Peking Man World Heritage Site at Zhoukoudian".

- ^ "Beijing's History". China Internet Information Center. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Beijing – Historical Background". The Economist. 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ^ Brian Hook, Beijing and Tianjin: Towards a Millennial Megalopolis, p. 2

- ^ "元大都土城遗址公园". Tuniu.com. Retrieved 15 June 2008. Template:Zh icon

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN=0-521-66991-X

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 23

- ^ Susan Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400–1900, p xxxiii

- ^ "An Illustrated Survey of Dikes and Dams in Jianghan Region". World Digital Library. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ "The Temple of Heaven". China.org. 13 April 2001. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Tiananmen Square". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 2008.

- ^ "Renewal of Ming Dynasty City Wall". Beijing This Month. 1 February 2003. Retrieved 14 June 2008.

- ^ Rosenburg, Matt T. "Largest Cities Through History". About.com. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 33

- ^ "Beijing – History – The Ming and Qing Dynasties". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 2008.

- ^ Elliott 2001, p. 98

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, pp. 119–120

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, pp. 133–134

- ^ MacKerras & Yorke 1991, p. 8

- ^ "Incident on 7 July 1937". Xinhua News Agency. 27 June 2005. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 166

- ^ Cheung, Andrew (1995). "Slogans, Symbols, and Legitimacy: The Case of Wang Jingwei's Nanjing Regime". Indiana University. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 168

- ^ " "毛主席八次接见红卫兵的组织工作" 中国共产党新闻网 7 April 2011 Template:Zh-icon

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 217

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 255

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 252

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 149

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, pp. 249–250

- ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, pp. 255–256

- ^ Picture Power:Tiananmen Standoff BBC News.

- ^ "Election". IOC. Archived from the original on 6 June 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Beijing". People's Daily. 2001. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Mherrerawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ 1991-2020 normals "Climate averages from 1991 to 2020". China Meteorological Administration. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023.

- ^ 1981-2010 extremes 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data [China Meteorological Data Network - WeatherBk Data] (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Extreme Temperatures Around the World". Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ 2021 February weather data "Global Surface Summary of the Day - GSOD". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 30 April 2023. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- ^ Burt, Christopher C. "UPDATE June 1: Record May Heat Wave in Northeast China, Koreas". Wunderground. Archived from the original on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ "Beijing records hottest June day since weather records began as heatwave hits China". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ "Beijing, China - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ David G. Streetsa, Joshua S. Fub, Carey J. Jangc, Jiming Haod, Kebin Hed, Xiaoyan Tange, Yuanhang Zhange, Zifa Wangf, Zuopan Lib, Qiang Zhanga, Litao Wangd, Binyu Wangc, Carolyne Yua, Air quality during the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games <[1]> accessed 23 April 2012

- ^ "Beijing petrol stations to close". BBC News. 15 February 2008. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Yardley, Jim (24 January 2008). "Smoggy Beijing Plans to Cut Traffic by Half for Olympics, Paper Says". New York Times. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Beijing residents debate road restrictions". UPI Asia Online. 9 September 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "New restrictions placed on public sector vehicles". China Daily. 16 September 2008. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Post-Olympics Beijing car restrictions to take effect next month". News.xinhuanet.com. 28 September 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Schmitt, Bertel (16 October 2008). "Chinese Numerology: Complicated Car Ban in Beijing". Chinaautobiz.blogspot.com. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ "China: Beijing launches Euro 4 standards". Automotiveworld.com. 4 January 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ "Only 'green' vehicles permitted to enter Beijing". Autonews.gasgoo.com. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ Demick, Barbara (2 October 2009). "Communist China celebrates 60th anniversary with instruments of war and words of peace". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b "Green Olympics Effort Draws UN Environment Chief to Beijing". Sundance Channel.

- ^ Imtiaz Muqbil (17 August 2008). "Golden effort maligned". Bangkok Post. (login required)

- ^ "Lessons from China on reducing air pollution". New Straits Times. 14 July 2012.

- ^ "Beijing keeping air cleaner after Olympics". ABC News. 9 August 2009.

- ^ Bristow, Michael (9 August 2009). "Beijing air 'cleaner' since Games". BBC News.

- ^ "Beijing air pollution off the charts, US says". AFP. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2011.

- ^ "Beijing pollution off the chart". 3 News NZ. 14 January 2013.

- ^ http://www.bjepb.gov.cn

- ^ a b Barbara Demick (29 October 2011). "U.S. Embassy air quality data undercut China's own assessment". Los Angeles Times. (login required)

- ^ "China says it made rain to wash off sand". MSNBC. 5 May 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Beijing hit by eighth sandstorm". BBC News. 17 April 2006. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Weaver, Lisa Rose (4 April 2002). "More than a dust storm in a Chinese teacup". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 January 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ "Beijing – Administration and society – Government". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 2008.

- ^ 北京市2010年第六次全国人口普查主要数据公报

- ^ Template:Zh icon "北京已率先进入后工业经济时代". china.com.cn. 20 March 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Global 500 2009: Cities". Fortune. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Beijing @ The China Perspective". Thechinaperspective.com. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Beijing tops PwC's list of cities' economic clout". China Daily. 12 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Beijing's Bankosphere". bankosphere.com. 11 August 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ Template:Zh icon "北京市金融业发展新闻发布会". zhengwu.beijing.gov.cn. 27 July 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ "Beijing annual GDP per capita hit $6,000". Beijing2008.cn. 3 April 2007. Archived from the original on 2 July 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Urban Construction". Beijing Municipal Bureau of Statistics. 2006. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ "ShiJingShan". Beijing Economic Information Center. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- ^ "Pirates weave tangled web on 'Spidey'". The Hollywood Reporter. Reuters. 27 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 May 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ "Capital Steel opens new branch to step up eastward relocation". People's Daily Online. 23 October 2005.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (18 July 2008). "Beijing abandons Mao's dream of workers' paradise". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ a b "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census". National Bureau of Statistics of China.

- ^ "省、自治区、直辖市的分性别、户口登记状况的人口". National Bureau of Statistics of China. April 2001. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "Sustainable urban expansion and transportation in a growing megacity: Consequences of urban sprawl for mobility on the urban fringe of Beijing". Habitat International. 31 October 2009.

- ^ "Age Composition and Dependency Ratio of Population by Region (2004) in China Statistics 2005". Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Current population situation of Beijing's ethnic minorities. 6th National Census, 2010.

- ^ "Praying for peace in their hometown, Tibetan students in Beijing speak out". People's Daily. Xinhua. 24 March 2008. Archived from the original on 27 May 2008. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "在华居住韩国人达百万 北京人数最多达二十万" (in Chinese). Xinhua.com. 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Ding, Ying (4 March 2008). "The Korean Mergence". Beijing Review. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Ye Jun (2008). "Got to have Seoul". China Daily: 5. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Department of Population, Social, Science and Technology Statistics of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司) and Department of Economic Development of the State Ethnic Affairs Commission of China (国家民族事务委员会经济发展司), eds. Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China (《2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料》). 2 vols. Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House (民族出版社), 2003. (ISBN 7-105-05425-5)

- ^ "Jingxi". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 2008.

- ^ "Beijing – Chinese Cloisonné Enamelware".

- ^ Levin, Dan (15 June 2008). "Beijing Lights Up the Night". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ "Beijing, Places of a Lifetime". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 3 August 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Imperial Palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties" (PDF). UNESCO World Heritage Center. 29 December 1986. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Beihai Park. UNECO World Heritage Tentative Lists[dead link]

- ^ Littlewood, Misty and Mark Littlewood (2008). Gateways to Beijing: a travel guide to Beijing. Armour Publishing Pte Ltd. p. 182. ISBN 981-4222-12-7.

- ^ "Summer Palace, an Imperial Garden in Beijing". UNESCO World Heritage Center. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ^ "Temple of Heaven: an Imperial Sacrificial Altar in Beijing". UNESCO World Heritage Center. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "About Beijing".

- ^ a b "Beijing's Museums & Galleries".

- ^ "Imperial Tombs of the Ming and Qing Dynasties". UNESCO World Heritage Center. 10 December 2003. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian". UNESCO World Heritage Center. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Great Wall". UNESCO World Heritage Center. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Business Buide to Beijing and North-East China (2006–2007 ed.). Hong Kong: China Briefing Media. 2006. p. 108. ISBN 988-98673-3-8. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Shen, Wei (16 February 2004). "Chorography to record rise and fall of Beijing's Hutongs". China Daily. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- ^ Amy Stone (Spring 2008). "Farewell to the Hutongs: Urban Development in Beijing". Dissent magazine. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Li, Dray-Novey & Kong 2007, p. 253

- ^ Gallagher, Sean (6 December 2006). "Beijing's urban makeover: the 'hutong' destruction". Open Democracy. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- ^ Some 350,000 residents were expected to be relocated to make room for the constructions of stadiums for the 2008 Summer Games.Davis 2006, p. 106

- ^ "Beijing Olympics Bird's Nest ready". BBC News. 28 June 2008. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ (Chinese) "北京市火车站大全" Last Accessed 8 August 2011

- ^ "Beijingers spend lives on road as traffic congestion worsens". China Daily. Xinhua News Agency. 6 October 2003. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ "Automobile numbers could be capped". China Daily. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Beijing city to have five mln cars on roads by year end". Gasgoo. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "To Tackle Traffic Jam, Beijing Sets New Car Plate Quota, Limits Out-of-Towners". ChinaAutoWeb.com.

- ^ "China plans to build world's biggest airport near Beijing". In.news.yahoo.com. 10 September 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Beijing's second airport to be ready by 2017". english.eastday.com. 22 June 2011.

- ^ "Beijing grants three-day visa-free access". TTGmice. 6 December 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ "30 subway lines to cover Beijing by 2020". China Daily. 28 May 2010. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (24 January 2010). "Campaign to boost cycling in Beijing". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ 北京市自然保护区名录(截至2011年底) 2012-08-24

- ^ (Chinese) 北京一级保护野生动物 Beijing Wildlife Conservation Association Accessed 2013-04-04

- ^ (Chinese) Beijing Wildlife Conservation Association Accessed 2013-04-04

- ^ Michael Rank, Wild leopards of Beijing, Danwei.org 2007-07-31

- ^ (Chinese) Beijing Aquatic Wildlife Rescue and Conservation Center Accessed 2013-04-05

- ^ a b (Chinese) 市花市树 eBeijing.gov.cn Accessed 2013-04-06

- ^ (Chinese) 北京市市树——国槐 2004-02-18

- ^ "Sister Cities". Beijing Municipal Government. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ a b Paris and Rome are "partner cities" due to an exclusive agreement between those two cities. "Le jumelage avec Rome" (in French). Municipalité de Paris. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^

"NYC's Sister Cities". Sister City Program of the City of New York. 2006. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ "Protocol and International Affairs". DC Office of the Secretary. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ^ "Twin cities of Riga". Riga City Council. Retrieved 27 July 2009.

- ^ Prefeitura.Sp – Descentralized Cooperation[dead link]

- ^ "International Relations – São Paulo City Hall – Official Sister Cities". Prefeitura.sp.gov.br. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^

"Canberra's international relationships – Canberra's international relationships". cmd.act.gov.au. Archived from the original on 12 November 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

"Sister Cities of Manila". 2008–2009 City Government of Manila. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Twinning Cities: International Relations" (PDF). Municipality of Tirana. tirana.gov.al. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

Further reading

- Cotterell, Arthur. (2007). The Imperial Capitals of China: An Inside View of the Celestial Empire. London: Pimlico. pp. 304 pages. ISBN 978-1-84595-009-5.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Palo Alto, California, United States: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4684-2. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Li, Lillian; Dray-Novey, Alison; Kong, Haili (2007). Beijing: From Imperial Capital to Olympic City. New York City, United States: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6473-4.

- Cammelli, Stefano Storia di Pechino e di come divenne capitale della Cina, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2004. ISBN 978-88-15-09910-5

- Harper, Damian, Beijing: City Guide, 7th Edition, Oakland, California: Lonely Planet Publications, 2007.

- Harper, Damian, Beijing: City Guide, 6th Edition, Oakland, California : Lonely Planet Publications, 2005. ISBN 1-74059-782-6.

- MacKerras, Colin; Yorke, Amanda (1991). The Cambridge Handbook of Contemporary China. Cambridge, England, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38755-8. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

External links

- Beijing Government website Template:Zh icon and Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead.

Beijing travel guide from Wikivoyage

Beijing travel guide from Wikivoyage- Economic profile for Beijing at HKTDC

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA

- Use dmy dates from November 2012

- Article Feedback 5 Additional Articles

- Articles including recorded pronunciations

- Beijing

- Capitals in Asia

- Host cities of the Summer Olympic Games

- Independent cities

- Metropolitan areas of China

- Municipalities of the People's Republic of China

- North China Plain

- World Digital Library related