Constantine IX Monomachos

| Constantine IX Κωνσταντῖνος Θ΄ Μονομάχος | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of the Byzantine Empire | |

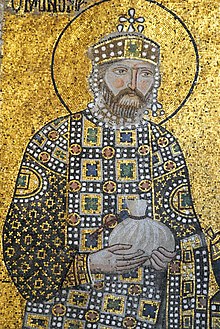

A mosaic in Hagia Sophia showing Constantine IX Monomachos. | |

| Reign | 11 June 1042 – 11 January 1055 |

| Coronation | 12 June 1042 |

| Predecessor | Zoe |

| Successor | Theodora |

| Born | c. 1000 Constantinople |

| Died | 11 January 1055 |

| Burial | |

| Wife Mistress | Helena Skleraina Empress Zoe Maria Skleraina Guarandukht of Georgia |

| Issue | Anastasia |

| Dynasty | Macedonian (by marriage) Monomachi family |

| Father | Theodosios Monomachos |

Constantine IX Monomachos, Latinized as Constantine IX Monomachus (Template:Lang-el), c. 1000 – January 11, 1055, reigned as Byzantine emperor from June 11, 1042 to January 11, 1055. He had been chosen by the Empress Zoe as a husband and co-emperor in 1042, although he had been exiled for conspiring against her previous husband, Emperor Michael IV the Paphlagonian. They ruled together until Zoe died in 1050.

Early life

Constantine Monomachos was the son of Theodosios Monomachos, an important bureaucrat under Basil II and Constantine VIII.[1] At some point Theodosios had been suspected of conspiracy and his son's career suffered accordingly.[2] Constantine's position improved after he married, as his second wife, a niece of Emperor Romanos III Argyros.[3] Catching the eye of the Empress Zoe, Constantine was exiled to Mytilene on the island of Lesbos by her second husband, Michael IV.[4] The death of Michael IV and the overthrow of Michael V in 1042, saw Constantine recalled from his place of exile and appointed judge in Greece.[5] However, prior to commencing his appointment, Constantine was summoned to Constantinople. There, the fragile working relationship between Michael V’s successors, the empresses Zoe and Theodora, was breaking down. After two months of increasing acrimony between the two, Zoe decided to search for a new husband, thereby hoping to prevent her sister from increasing her popularity and authority.[6] After her first preference displayed his contempt for the empress, and her second died under mysterious circumstances,[3] Zoe’s remembered the handsome and urbane Constantine. The pair were married on June 11, 1042, without the participation of Patriarch Alexius I of Constantinople, who refused to officiate over a third marriage (for both spouses).[2] On the following day Constantine was formally proclaimed emperor together with Zoe and her sister Theodora.

Reign

Constantine continued the purge instituted by Zoe and Theodora, removing the relatives of Michael V from the court.[7] The new emperor was pleasure-loving[8] and prone to violent outbursts on suspicion of conspiracy.[9] He was heavily influenced by his mistress, Maria Skleraina, a niece of his second wife, and Maria's relatives. In August 1042, under the influence of the Skleroi[10] the emperor relieved General George Maniakes from his command in Italy, and Maniakes rebelled, declaring himself emperor in September.[11] He transferred his troops into the Balkans and was about to defeat Constantine's army in battle, when he was wounded and died on the field, ending the crisis in 1043.[12]

Immediately after the victory, Constantine was attacked by a fleet from Kievan Rus';[12] it is "incontrovertible that a Rus' detachment took part in the Maniakes rebellion".[13] They too were defeated, with the help of Greek fire.[14] Constantine married his daughter Anastasia to the future Prince Vsevolod I of Kiev, the favorite son of his dangerous opponent Yaroslav I the Wise by Ingegerd Olofsdotter.

Constantine IX’s preferential treatment of Maria Skleraina in the early part of his reign saw rumours spread that she was planning to murder both Zoe and Theodora.[15] This led to a popular uprising by the citizens of Constantinople in 1044, which came dangerously close to actually harming Constantine who was participating in a religious procession along the streets of Constantinople.[16] The mob was only quietened by the appearance of Zoe and Theodora at a balcony, who reassured the people that they were not in any danger of assassination.[16]

In 1045 Constantine annexed the Armenian kingdom of Ani,[17] according to a treaty agreed with king John Smbat and Basil II, but this expansion merely exposed the empire to new enemies. In 1046 the Byzantines came into contact for the first time with the Seljuk Turks.[18] They met in battle in Armenia in 1048, and settled a truce the following year.[19] Even if Seljuk rulers were willing to abide by the treaty, their unruly Turcoman allies showed much less restraint. Thus Constantine weakened the Byzantine forces, which in turn led to their cataclysmic defeat at the battle of Manzikert in 1071.[20]

Constantine also began persecuting the Armenian Church, trying to force it into union with the Orthodox church.[18]

In 1047 Constantine was faced by the rebellion of his nephew Leo Tornikios in Adrianople.[10] Tornikios gained support in most of Thrace and vainly attempted to take Constantinople. Forced to retreat, Tornikios failed in another siege, and was captured during his flight.[20] The revolt had weakened Byzantine defenses in the Balkans and in 1048 the area was raided by the Pechenegs,[21] who continued to plunder it for the next five years. The emperor's efforts to contain the enemy through diplomacy merely exacerbated the situation, as rival Pecheneg leaders clashed on Byzantine ground, and Pecheneg settlers were allowed to live in compact settlement in the Balkans, making it difficult to suppress their rebellion.[22] Faced with such difficulties, Constantine may have sought Hungarian support.

Internally, Constantine sought to secure his position by favoring the nobility (dynatoi) and granted generous tax immunities to major landowners and the church. Similarly, he seems to have taken recourse to the pronoia system, a sort of Byzantine feudal contract in which tracts of land (or the tax revenue from it) were granted to particular individuals in exchange for contributing and maintaining military forces.[4][23] Both expedients gradually compromised the effectiveness of the state and contributed to the development of the crisis that engulfed Byzantium in the second half of the 11th century.

In 1054 the centuries-old differences between the Greek and Roman churches led to their final separation.[24] Legates from Pope Leo IX excommunicated the Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Keroularios when Keroularios would not agree to adopt western church practises, and in return Keroularios excommunicated the legates.[25] This sabotaged Constantine's attempts to ally with the Pope against the Normans, who had taken advantage of Maniakes' disappearance to take over Southern Italy.[26]

Constantine tried to intervene, but he fell ill and died on January 11 of the following year.[27] Although he was persuaded by his councillors, chiefly the logothetes tou dromou John, to ignore the rights of Theodora and to pass the throne to the doux of Bulgaria, Nikephoros Proteuon,[28] the elderly daughter of Constantine VIII who had ruled with her sister Zoe since 1042, was recalled from her retirement and named empress.[29]

Overall, his reign was a disaster for the Byzantine empire;[2] in particular, the military weakness for which he was largely responsible greatly contributed to the subsequent loss of Asia Minor to the Turks, after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

Architecture and Art

Constantine IX was also a patron of the arts and literature, and during his reign the university in Constantinople expanded its juridical and philosophical programs. The literary circle at court included the philosopher and historian Michael Psellos, whose Chronographia records the history of Constantine's reign. Psellos left a physical description of Constantine in his Chronographia: he was "ruddy as the sun, but all his breast, and down to his feet... [were] colored the purest white all over, with exquisite accuracy. When he was in his prime, before his limbs lost their virility, anyone who cared to look at him closely would surely have likened his head to the sun in its glory, so radiant was it, and his hair to the rays of the sun, while in the rest of his body he would have seen the purest and most translucent crystal."[30]

Immediately upon ascending to the throne in 1042, Constantine IX set about restoring the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which had been substantially destroyed in 1009 by Caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah.[31] Permitted by a treaty with al-Hakim's son Ali az-Zahir and Byzantine Emperor Romanus III, it was Constantine IX who finally funded the reconstruction of the Church and other Christian establishments in the Holy Land.[32] The reconstruction took place during the reign of the Caliph Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah.

Family

Constantine Monomachos was married three times:

- to a wife of unknown identity.

- to Helena Skleraina, daughter of Basil Skleros, great-granddaughter of Bardas Skleros, and niece of Emperor Romanus III.

- to the Empress Zoe

After the death of his second wife, Constantine also took her first cousin Maria Skleraina as his mistress. At the time of Constantine's death in January 1055, the emperor had another mistress, a certain "Alan princess", probably Irene, daughter of the Georgian Bagratid prince Demetrius.[33]

He had no children with his first wife or with the ageing Zoe. With either Helena or Maria Sklerina he had a daughter named Anastasia, who married Vsevolod I of Kiev in 1046. Constantine's family name Monomachos ("one who fights alone") was inherited by his Kievan grandson, Vladimir II Monomakh.[1]

Sources

Primary Sources

- Michael Psellus, Fourteen Byzantine Rulers, trans. E.R.A. Sewter (Penguin, 1966). ISBN 0-14-044169-7

Secondary Sources

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- Norwich, John Julius (1993), Byzantium: The Apogee, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-011448-3

- Canduci, Alexander (2010), Triumph & Tragedy: The Rise and Fall of Rome's Immortal Emperors, Pier 9, ISBN 978-1-74196-598-8

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997), A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2630-2

- Michael Angold, The Byzantine empire 1025–1204 (Longman, 2nd edition, 1997). ISBN 0-582-29468-1

- Jonathan Harris, Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium (Hambledon/Continuum, 2007). ISBN 978-1-84725-179-4

- George Finlay, History of the Byzantine Empire from 716 – 1057, William Blackwood & Sons, 1853

References

- ^ a b Kazhdan, pg. 1398

- ^ a b c Norwich, pg. 307

- ^ a b Norwich, pg. 306

- ^ a b Kazhdan, pg. 504

- ^ Finlay, pg. 500

- ^ Finlay, pg. 499

- ^ Finlay, pg. 505

- ^ Norwich, pg. 308

- ^ Finlay, pg, 510

- ^ a b Canduci, pg. 269

- ^ Norwich, pg. 310

- ^ a b Norwich, pg. 311

- ^ Quoted from: Litavrin, Grigory. Rus'-Byzantine Relations in the 11th and 12th Centuries. // History of Byzantium, vol. 2, chapter 15, p. 347-352. Moscow: Nauka, 1967 (online)

- ^ Finlay, pg. 514

- ^ Norwich, pg. 309

- ^ a b Finlay, pg. 503

- ^ Norwich, pg. 340

- ^ a b Norwich, pg. 341

- ^ Finlay, pg. 520

- ^ a b Norwich, pg. 314

- ^ Finlay, pg. 515

- ^ Norwich, pg. 315

- ^ Finlay, pg. 504

- ^ Canduci, pg. 268

- ^ Norwich, pg. 321

- ^ Norwich, pg. 316

- ^ Norwich, pg. 324

- ^ Finlay, pg. 527

- ^ Treadgold, pg. 596

- ^ Psellos, 126:2–5

- ^ Finlay, pg. 468

- ^ Ousterhout, Robert (1989). "Rebuilding the Temple: Constantine Monomachus and the Holy Sepulchre". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 48 (1): 66–78. doi:10.2307/990407.

- ^ Lynda Garland with Stephen H. Rapp Jr. (2006). 'of Alania'. An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors. Retrieved on April 3, 2011.