Endangered species

| Conservation status |

|---|

| Extinct |

| Threatened |

| Lower Risk |

| Other categories |

| Related topics |

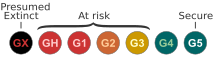

Comparison of Red List classes above and NatureServe status below  |

An endangered species is a species of organisms facing a very high risk of extinction. The phrase is used vaguely in common parlance for any species fitting this description, but its use by conservation biologists typically refers to those designated Endangered in the IUCN Red List, where it is the second most severe conservation status for wild populations, following Critically Endangered. There are currently 3079 animals and 2655 plants classified as Endangered worldwide, compared with 1998 levels of 1102 and 1197, respectively.[1] The amount, population trend, and conservation status of each species can be found in the Lists of organisms by population.

Many nations have laws offering protection to conservation reliant species: for example, forbidding hunting, restricting land development or creating preserves.

Conservation status

The conservation status of a species is an indicator of the likelihood of that endangered species becoming extinct. Many factors are taken into account when assessing the conservation status of a species, including statistics such as the number remaining, the overall increase or decrease in the population over time, breeding success rates, known threats, and so on.[2] The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the best-known worldwide conservation status listing and ranking system.[3]

It has been estimated that over 40% of all living species on Earth are at risk of going extinct.[4] Internationally, 199 countries have signed an accord agreeing to create Biodiversity Action Plans to protect endangered and other threatened species. In the United States this plan is usually called a species Recovery Plan.

IUCN Red List

IUCN Red List refers to a specific category of threatened species, and may include critically endangered species. The IUCN Red List uses the term endangered species as a specific category of imperilment, rather than as a general term. Under the IUCN Categories and Criteria, endangered species is between critically endangered and vulnerable. Also critically endangered species may also be counted as endangered species and fill all the criteria

The more general term used by the IUCN for species at risk of extinction is threatened species, which also includes the less-at-risk category of vulnerable species together with endangered and critically endangered.

IUCN categories, and some animals in those categories, include:

- Extinct: Examples: Atlas bear, aurochs, Bali tiger, blackfin cisco, Caribbean monk seal, Carolina parakeet, Caspian tiger, dusky seaside sparrow, eastern cougar, elephant bird, golden toad, great auk, Haast's eagle, Japanese sea lion, Javan tiger, labrador duck, moa, passenger pigeon, pterosaurs, saber-toothed cat, Schomburgk's deer, short-faced bear, Steller's sea cow, thylacine, toolache wallaby, western black rhinoceros, woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros.

- Extinct in the wild: captive individuals survive, but there is no free-living, natural population. Examples: Barbary lion (maybe extinct), Catarina pupfish, Hawaiian crow,, Scimitar oryx, Socorro dove, Wyoming toad

- Critically endangered: faces an extremely high risk of extinction in the immediate future. Examples: addax, African wild ass, Alabama cavefish, Amur leopard, Arakan forest turtle, Asiatic cheetah, axolotl, bactrian camel, Brazilian merganser, brown spider monkey, California condor, Chinese alligator, Chinese giant salamander, gharial, Hawaiian monk seal, Iberian lynx, Island fox, Javan rhino, kakapo, leatherback sea turtle, Mediterranean monk seal, Mexican wolf, mountain gorilla, Philippine eagle, red wolf, saiga, Siamese crocodile, Spix's macaw, southern bluefin tuna, Sumatran orangutan, Sumatran rhinoceros, vaquita, Yangtze river dolphin, northern white rhinoceros

- Endangered: faces a very high risk of extinction in the near future. Examples: African penguin, African wild dog, Asian elephant, Asiatic lion, blue whale, bonobo, Bornean orangutan, common chimpanzee, dhole, eastern lowland gorilla, Ethiopian wolf, hispid hare, giant otter, giant panda, goliath frog, green sea turtle, Grevy's zebra, hyacinth macaw, Japanese crane, Lear's macaw, Malayan tapir, markhor, Persian leopard, proboscis monkey, pygmy hippopotamus, red-breasted goose, Rothschild's giraffe, snow leopard, Steller's sea lion, scopas tang, takhi, tiger, Vietnamese pheasant, volcano rabbit, wild water buffalo

- Vulnerable: faces a high risk of extinction in the medium-term. Examples: African grey parrot, African elephant, American paddlefish, common carp, clouded leopard, cheetah, dugong, far eastern curlew, fossa, Galapagos tortoise, gaur, blue-eyed cockatoo, golden hamster, whale shark, crowned crane, hippopotamus, Humboldt penguin, Indian rhinoceros, Komodo dragon, lesser white-fronted goose, lion, mandrill, maned sloth, mountain zebra, polar bear, red panda, sloth bear, takin, yak

- Near threatened: may be considered threatened in the near future. Examples: American bison, starry blenny, Asian golden cat, blue-billed duck, emperor goose, emperor penguin, Eurasian curlew, jaguar, leopard, Magellanic penguin, maned wolf, narwhal, okapi, solitary eagle, white rhinoceros, striped hyena, tiger shark, white eared pheasant

- Least concern: no immediate threat to the survival of the species. Examples: American alligator, American crow, Indian peafowl, baboon, bald eagle, brown bear, brown rat, brown-throated sloth, Canada goose, cane toad, common wood pigeon, cougar, common frog, orca, giraffe, grey wolf, house mouse, wolverine[6] human, palm cockatoo, cowfish, mallard, meerkat, mute swan, platypus, red-billed quelea, red-tailed hawk, rock pigeon, scarlet macaw, southern elephant seal, milk shark, red howler monkey

United States

Under the Endangered Species Act in the United States, "endangered" is the more protected of the two categories. The Salt Creek tiger beetle (Cicindela nevadica lincolniana) is an example of an endangered subspecies protected under the ESA.

In the United States alone, the "known species threatened with extinction is ten times higher than the number protected under the Endangered Species Act" (Wilcove & Master, 2008, p. 414). The US Fish and Wildlife Service as well as the National Marine Fisheries Service are held responsible for classifying and protecting endangered species, yet, adding a particular species to the list is a long, controversial process and in reality it represents only a fraction of imperiled plant and animal life (Wilcove & Master, 2008, p. 414).

Some endangered species laws are controversial. Typical areas of controversy include: criteria for placing a species on the endangered species list, and criteria for removing a species from the list once its population has recovered; whether restrictions on land development constitute a "taking" of land by the government; the related question of whether private landowners should be compensated for the loss of uses of their lands; and obtaining reasonable exceptions to protection laws. Also lobbying from hunters and various industries like the petroleum industry, construction industry, and logging, has been an obstacle in establishing endangered species laws.

The Bush administration lifted a policy that required federal officials to consult a wildlife expert before taking actions that could damage endangered species. Under the Obama administration, this policy has been reinstated.[7]

Being listed as an endangered species can have negative effect since it could make a species more desirable for collectors and poachers.[8] This effect is potentially reducible, such as in China where commercially farmed turtles may be reducing some of the pressure to poach endangered species.[9]

Another problem with the listing species is its effect of inciting the use of the "shoot, shovel, and shut-up" method of clearing endangered species from an area of land. Some landowners currently may perceive a diminution in value for their land after finding an endangered animal on it. They have allegedly opted to silently kill and bury the animals or destroy habitat, thus removing the problem from their land, but at the same time further reducing the population of an endangered species.[10] The effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act, which coined the term "endangered species", has been questioned by business advocacy groups and their publications, but is nevertheless widely recognized as an effective recovery tool by wildlife scientists who work with the species. Nineteen species have been delisted and recovered[11] and 93% of listed species in the northeastern United States have a recovering or stable population.[12]

Currently, 1,556 known species in the world have been identified as endangered, or near extinction, and are under protection by government law (Glenn, 2006, Webpage). This approximation, however, does not take into consideration the number of species threatened with endangerment that are not included under the protection of such laws as the Endangered Species Act. According to NatureServe's global conservation status, approximately thirteen percent of vertebrates (excluding marine fish), seventeen percent of vascular plants, and six to eighteen percent of fungi are considered imperiled (Wilcove & Master, 2008, p. 415-416). Thus, in total, between seven and eighteen percent of the United States' known animals, fungi, and plants are near extinction (Wilcove & Master, 2008, p. 416). This total is substantially more than the number of species protected under the Endangered Species Act in the United States.

NatureServe conservation status

NatureServe and its member programs and collaborators use a suite of factors to assess the conservation status of plant, animal, and fungal species, as well as ecological communities and systems. These assessments lead to the designation of a conservation status rank. For species these ranks provide an estimate of extinction risk, while for ecological communities and systems they provide an estimate of the risk of elimination. Conservation status ranks for how ecological systems in North America are currently under development.

Conservation status ranks are based on a one to five scale, ranging from critically imperiled (G1) to demonstrably secure (G5). Status is assessed and documented at three distinct geographic scales-global (G), national (N), and state/province (S). The numbers have the following meaning:

- 1 = critically imperiled

- 2 = imperiled

- 3 = vulnerable

- 4 = apparently secure

- 5 = secure

For example, G1 would indicate that a species is critically imperiled across its entire range (i.e., globally). In this sense the species as a whole is regarded as being at very high risk of extinction. A rank of S3 would indicate the species is vulnerable and at moderate risk within a particular state or province, even though it may be more secure elsewhere.

Species and ecosystems are designated with either an "X" (presumed extinct or extirpated) if there is no expectation that they still survive, or an "H" (possibly extinct or extirpated) if they are known only from historical records but there is a chance they may still exist. Other variants and qualifiers are used to add information or indicate any range of uncertainty. See the following conservation status rank definitions for complete descriptions of ranks and qualifiers.

Climate change

Before anthropogenic global warming, species were subjected mainly to regional pressures, such as overhunting and habitat destruction. With the acceleration of anthropogenic global warming since the industrial revolution, climate change has begun to influence species safety. Nigel Stork, in the article "Re-assessing Extinction Rate" explains, "the key cause of extinction being climate change, and in particular rising temperatures, rather than deforestation alone." Stork believes climate change is the major issue as to why species are becoming endangered. Stork claims rising temperature on a local and global level are making it harder for species to reproduce. As global warming continues, species are no longer able to survive and their kind starts to deteriorate. This is a repeating cycle that is starting to increase at a rapid rate because of climate change therefore landing many species on the endangered species list.[13]

Conservation

Captive breeding

Captive breeding is the process of breeding rare or endangered species in human controlled environments with restricted settings, such as wildlife preserves, zoos and other conservation facilities. Captive breeding is meant to save species from going extinct. It is supposed to stabilize the population of the species so it is no longer at risk for disappearing.[14]

This technique has been used with success for many species for some time, with probably the oldest known such instances of captive mating being attributed to menageries of European and Asian rulers, a case in point being the Père David's deer. However, captive breeding techniques are usually difficult to implement for highly mobile species like some migratory birds (e.g. cranes) and fishes (e.g. hilsa). Additionally, if the captive breeding population is too small, inbreeding may occur due to a reduced gene pool; this may lead to the population lacking immunity to diseases.

Private farming

Whereas poaching causes substantial reductions in endangered animal populations, legal private farming for profit has the opposite effect. Legal private farming has caused substantial increases in the populations of both the southern black rhinoceros and the southern white rhinoceros. Dr Richard Emslie, a scientific officer at the IUCN, said of such programs, "Effective law enforcement has become much easier now that the animals are largely privately owned... We have been able to bring local communities into the conservation programmes. There are increasingly strong economic incentives attached to looking after rhinos rather than simply poaching: from eco-tourism or selling them on for a profit. So many owners are keeping them secure. The private sector has been key to helping our work."[15]

Conservation experts view the effect of China's turtle farming on the wild turtle populations of China and South-Eastern Asia—many of which are endangered—as "poorly understood".[16] While they commend the gradual replacement of wild-caught turtles with farm-raised turtles in the marketplace (the percentage of farm-raised individuals in the "visible" trade grew from around 30% in 2000 to around 70% in 2007),[17] they are concerned with the fact that a lot of wild animals are caught to provide farmers with breeding stock. As the conservation expert Peter Paul van Dijk noted, turtle farmers often believe in the superiority of wild-caught animals as the breeding stock, which may create an incentive for turtle hunters to seek and catch the very last remaining wild specimens of some endangered turtle species.[17]

In 2009, researchers in Australia managed for the first time to coax southern bluefin tuna to breed in landlocked tanks, opening up the possibility of using fish farming as a way to save the species from the problems of overfishing in the wild.[18] Will Sasso Lemon

Gallery

-

The endangered island fox

-

The endangered sea otter

-

American bison skull heap. There were as few as 750 bison in 1890 from economic-driven overhunting.

-

Immature California condor

-

The Siberian tiger is a subspecies of tiger that is endangered

See also

- ARKive

- Biodiversity

- Critically Endangered

- Endangered plants of Europe

- Endangered Species Act

- Endangered Species Coalition (ESC)

- Ex-situ conservation

- Extinction

- Holocene extinction

- Habitat fragmentation

- Hawaiian honeycreeper conservation

- In-situ conservation

- IUCN Red List

- IUCN Red List Critically Endangered species

- IUCN Red List endangered animal species

- The Last Paradises: On the Track of Rare Animals (1967 film)

- List of endangered species in India

- List of endangered species in North America

- List of National Wildlife Refuges established for endangered species

- Overexploitation

- NatureServe conservation status

- Rare species

- Red Data Book of the Russian Federation

- Red and Blue-listed

- Threatened species

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service list of endangered species

- World Conference on Breeding Endangered Species in Captivity as an Aid to their Survival (WCBESCAS)

- World Conservation Union (IUCN)

- World Wide Fund for Nature

Notes

- ^ "IUCN Red List version 2012.2: Table 2: Changes in numbers of species in the threatened categories (CR, EN, VU) from 1996 to 2012 (IUCN Red List version 2012.2) for the major taxonomic groups on the Red List" (PDF). IUCN. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "NatureServe Conservation Status". NatureServe. April 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "Red List Overview". IUCN. February 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "Threatened Species". Conservation and Wildlife. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ "The Tiger". Sundarbans Tiger Project. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Template:IUCN2009.2

- ^ FWS.gov

- ^ Courchamp, Franck. "Rarity Value and Species Extinction: The Anthropogenic Allee Effect". PLoS Biology. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dharmananda, Subhuti. "Endangered Species issues affecting turtles and tortoises used in Chinese medicine". Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ^ "Shoot, Shovel and Shut Up". Reasononline. Reason Magazine. 2003-12-31. Retrieved 2006-12-23.

- ^ "USFWS Threatened and Endangered Species System (TESS)". U. S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ Success Stories for Endangered Species Act

- ^ Stork, Nigel (2010). "Re-assessing Current Extinction Rates" (2).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Captive Breeding Populations - National Zoo| FONZ". Nationalzoo.si.edu. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ He's black, and he's back! Private enterprise saves southern Africa's rhino from extinction, The Independent, June 17, 2008

- ^ Shi, Haitao; Parham, James F.; Fan, Zhiyong; Hong, Meiling; Yin, Feng (2008-01-01). "Evidence for the massive scale of turtle farming in China". Oryx. Vol. 42. Cambridge University Press. pp. 147–150. doi:10.1017/S0030605308000562. Retrieved 2009-12-26.

- ^ a b "Turtle farms threaten rare species, experts say". Fish Farmer, 30 March 2007. Their source is an article by James Parham, Shi Haitao, and two other authors, published in Feb 2007 in the journal Conservation Biology

- ^ The Top 10 Everything of 2009: Top 10 Scientific Discoveries: 5. Breeding Tuna on Land, Time magazine, December 8, 2009

References

- Glenn, C. R. 2006. "Earth's Endangered Creatures", Accessed 9/30/2008

- Ishwaran, N., & Erdelen, W. (2005, May). Biodiversity Futures, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 3(4), 179. Retrieved September 23, 2008

- Kotiaho, J. S., Kaitala, V., Komonen, A., Päivinen, J. P., & Ehrlich, P. R. (2005, February 8). Predicting the Risk of Extinction from Shared Ecological Characteristics, proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(6), 1963-1967. Retrieved September 24, 2008

- Minteer, B. A., & Collins, J. P. (2005, August). Why we need an "Ecological Ethics".

- Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 3(6), 332-337. Retrieved September 22, 2008

- Raloff, J. (2006, August 5). Preserving Paradise, Science News, 170(6), 92. Retrieved September 22, 2008,

- Wilcove, D. S., & Master L. L. (2008, October). How Many Endangered Species are there in the United States? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 3(8), 414-420. Retrieved September 22, 2008.

External links

- List of species with the category Endangered as identified by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- Endangered Species from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Endangered Species & Wetlands Report Independent print and online newsletter covering the ESA, wetlands and regulatory takings.

- USFWS numerical summary of listed species in US and elsewhere