History of Bulgaria

| History of Bulgaria |

|---|

|

|

|

Main category |

The history of Bulgaria as a separate country began in the 7th century with the arrival of the Bulgars and the foundation of the First Bulgarian Empire together with the local seven Slavic tribes, a union recognized by Byzantium in 681. A country in the middle of the ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse Balkan Peninsula, Bulgaria has seen many twists and turns in its long history and has been a prospering empire stretching to a coastline on the Black, Aegean and Adriatic Seas and a cultural centre of Slavic Europe, but also a land long dominated by a foreign state, once by the Byzantine Empire and once by the Ottoman Empire.

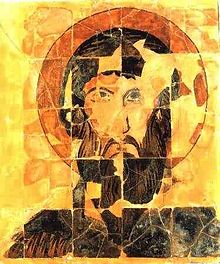

Bulgars

The Bulgars arrived in the Balkans in the 7th century from central Asia, but their exact origin is not entirely clear. The established theory is that the Bulgars are related to the Huns, and more distantly the Turks. However, this position is increasingly being challenged by a theory claiming Aryan-Pamirian origin for the Bulgars. Clues for this can be found in the advanced calendar and system of government of the early Bulgars.

The Bulgars were governed by hereditary khans. There were several aristocratic families whose members, bearing military titles, formed a governing class. Bulgars were monotheistic, worshipping a god called "Tangra".

The migration of Bulgars to the European continent started as early as the 2nd century when branches of Bulgars settled on the plains between the Caspian and the Black Sea. Between 351 and 389 AD, some of these crossed the Caucasus and settled in Armenia. They were eventually assimilated by the Armenians.

Swept by the Hunnish wave at the beginning of the 4th century, other numerous Bulgarian tribes broke loose from their settlements in central Asia to migrate to the fertile lands along the lower valleys of the Donets and the Don rivers and the Azov seashore. Some of these remained for centuries in their new settlements, whereas others moved on with the Huns towards Central Europe, settling in Pannonia.

In the 632 AD, the Bulgars, led by Khan Kubrat formed an independent state, often called Great Bulgaria, between the lower course of the Danube to the west, the Black and the Azov Seas to the south, the Kuban river to the east, and the Donets river to the north. The capital of the state was Phanagoria, on the Azov.

The pressure from peoples further east (such as the Khazars) led to the dissolution of Great Bulgaria in the second half of the 7th century. One Bulgar tribe migrated to the confluence of the Volga and Kama Rivers in what is now the Russian Federation (see Volga Bulgaria). Most of them converted to Islam in the beginning in the 8th century and maintained an independent state until the 13th century, others, like the present-day Chuvash, converted to Christianity. Smaller Bulgar tribes seceded in Pannonia and in Italy, northwest of Naples, while other Bulgars sought refuge with the Lombards. Another group of Bulgars remained in the land north of the Black and the Azov Seas. They were, however, soon subdued by the Khazars. These Bulgars converted to Judaism in the 9th century, along with the Khazars, and were eventually assimilated.

Yet another Bulgar tribe, led by Khan Asparuh, moved westward, occupying today’s southern Bessarabia. After a successful war with Byzantium in 680 AD, Asparuh’s khanate conquered Moesia and Dobrudja and was recognised as an independent state under the subsequent treaty signed with the Byzantine Empire in 681 AD. The same year is usually regarded as the year of the establishment of present-day Bulgaria.

Another possibility is that Great Bulgaria, despite suffering a major loss of territory at the hands of the Khazars, managed to defeat them in the early 670s. Khan Asparuh, the successor to Khan Kubrat, may have subsequently conquered Moesia and Dobrudja from the Byzantine Empire in 680 AD. Thus, the date for the establishment of present-day Bulgaria could be considered 632 AD as opposed to 681 AD, since the state of Great Bulgaria may have been continuous with the Danubian Bulgarian state.

First Bulgarian Empire

During the time of the late Roman Empire, the lands of present-day Bulgaria had been organised in several provinces - Scythia (Scythia Minor), Moesia (Upper and Lower), Thrace, Macedonia (First and Second), Dacia (Coastal and Inner, both situated south of Danube), Dardania, Rhodope and Hemimont, and had a mixed population of Thracians, Greeks and Dacians, most of whom spoke either Greek or a Latin-derived language known as Romance. Several consecutive waves of Slavic migration throughout the 6th and the early 7th century led to a dramatic change of the demographics of the region and its almost complete "Slavonisation".

Under the warrior Khan Krum (802-814), Bulgaria expanded northwest and southwards, occupying the lands between middle Danube and Moldova, the whole territory of present-day Romania, Sofia in 809 and Adrianople in 813, and threatening Constantinople itself. Khan Krum implemented law reform intending to reduce the poverty and to strengthen the social ties in his vastly enlarged state. During the reign of Khan Omurtag (814-831), the northwestern boundaries with the Frankish Empire were firmly settled along the middle Danube and magnificent palace, pagan temples, ruler's residence, fortress, citadel, water-main and bath were built in Bulgarian capital Pliska, mainly of stone and brick.

Under Boris I the Bulgarians became Christians, and the Ecumenical Patriarch agreed to allow an autonomous Bulgarian Archbishop at Pliska. Missionaries from Constantinople, Cyril and Methodius, devised the Glagolitic alphabet, which was adopted in the Bulgarian Empire around 886. The alphabet and the Old Bulgarian language gave rise to a rich literary and cultural activity centered around the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools, established by order of Boris I in 886. In the beginning of 10th century AD, a new alphabet - the Cyrillic alphabet - was developed on the basis of Greek and Glagolitic cursive at the Preslav Literary School. According to an alternative theory, the alphabet was devised at the Ohrid Literary School by Saint Climent of Ohrid, a Bulgarian scholar and disciple of Cyril and Methodius.

By the late 9th and the beginning of the 10th century, Bulgaria extended to Epirus and Thessaly in the south, Bosnia in the west and controlled the whole of present-day Romania and eastern Hungary to the north. A Serbian state came into existence as a dependency of the Bulgarian Empire. Under Tsar Simeon I (Simeon the Great), who was educated in Constantinople, Bulgaria became again a serious threat to the Byzantine Empire. Simeon hoped to take Constantinople and make himself Emperor of both Bulgarians and Greeks, and fought a series of wars with the Byzantines through his long reign (893-927). The war boundary towards the end of his rule reached Peloponnese in the south. Simeon proclaimed himself "Tsar (Caesar) of the Bulgarians and the Greeks," a title which was recognised by the Pope, but not of course by the Byzantine Emperor.

Second Bulgarian Empire

The Byzantines ruled Bulgaria from 1018 to 1185, subordinating the independent Bulgarian Orthodox Church to the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople but otherwise interfering little in Bulgarian local affairs. There were rebellions against Byzantine rule in 1040-41, the 1070s and the 1080s, but these failed. By the late 12th century the Byzantines were in decline after a series of wars with the Hungarians and the Serbs. In 1185 Peter and Asen, leading nobles of supposed and contested Bulgarian, Cuman, Vlach or mixed origin, led a revolt against Byzantine rule and Peter declared himself Tsar Peter II (also known as Theodore Peter). The following year the Byzantines were forced to recognise Bulgaria's independence. Peter styled himself "Tsar of the Bulgars, Greeks and Vlachs".

Resurrected Bulgaria occupied the territory between the Black Sea, the Danube and Stara Planina, including a part of eastern Macedonia and the valley of the Morava. It also exercised control over Wallachia and Moldova. Tsar Kaloyan (1197-1207) entered a union with the Papacy, thereby securing the recognition of his title of "Rex" although he desired to be recognized as "Emperor" or "Tsar". He waged wars on the Byzantine Empire and (after 1204) on the Knights of the Fourth Crusade, conquering large parts of Thrace, the Rhodopes, as well as the whole of Macedonia. The power of the Hungarians and to some extent the Serbs prevented significant expansion to the west and northwest. Under Ivan Asen II (1218-1241), Bulgaria once again became a regional power, occupying Belgrade and Albania. In an inscription from Turnovo in 1230 he entitled himself "In Christ the Lord faithful Tsar and autocrat of the Bulgarians, son of the old Asen". The Bulgarian Orthodox Patriarchate was restored in 1235 with approval of all eastern Patriarchates, thus putting an end to the union with the Papacy. Ivan Asen II had a reputation as a wise and humane ruler, and opened relations with the Catholic west, especially Venice and Genoa, to reduce the influence of the Byzantines over his country.

However, weakened 14th-century Bulgaria was no match for a new threat from the south, the Ottoman Turks, who crossed into Europe in 1354. In 1362 they captured Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and in 1382 they took Sofia. The Ottomans then turned their attentions to the Serbs, whom they routed at Kosovo Polje in 1389. In 1393 the Ottomans occupied Turnovo after a three-month siege. It is thought that the south gate was opened from inside and so the Ottomans managed to enter the fortress. In 1396 the Kingdom (Tsardom) of Vidin was also occupied, bringing the Second Bulgarian Empire and Bulgarian independence to an end.

Ottoman Bulgaria

The Ottomans reorganised the Bulgarian territories as the Beyerlik of Rumili, ruled by a Beylerbey at Sofia. This territory, which included Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia, was divided into several sanjaks, each ruled by a Sanjakbey accountable to the Beylerbey. Significant part of the conquered land was parcelled out to the Sultan's followers, who held it as feudal fiefs (small timars, medium ziyamet and large hases) directly from him. That category of land could not be sold or inherited, but reverted to the Sultan when the fiefholder died. The rest of the lands were organized as private possessions of the Sultan or Ottoman nobility, called "mülk", and also as economic base for religious foundations, called "vakιf". Bulgarians gave multiple regularly paid taxes as a tithe ("yushur"), a capitation tax ("dzhizie"), a land tax ("ispench"), a levy on commerce and so on and also various group of irregularly collected taxes, products and corvees ("avariz").

The Ottomans did not normally require the Christians to become Muslims. Nevertheless, there were many cases of individual or mass forced islamization, especially in the Rhodopes. Non-Muslims did not serve in the Sultan's army. The exception to this were some groups of the population with specific statute, usually used for auxiliary or rear services, and the famous "tribute of children" (or blood tax), also known as the "devsirme", whereby every fifth young boy was taken to be trained as a warrior of the Empire. These boys went through harsh religious and military training that turned them into an elite corps subservient to the Sultan. They made up the corps of Janissaries (yenicheri or "new force"), an elite unit of the Ottoman army.

National awakening

Bulgarian nationalism emerged in the early 19th century under the influence of western ideas such as liberalism and nationalism, which trickled into the country after the French Revolution, mostly via Greece. The Greek revolt against the Ottomans which began in 1821 (see History of Ottoman Greece), also influenced the small Bulgarian educated class. But Greek influence was limited by the general Bulgarian resentment of Greek control of the Bulgarian Church, and it was the struggle to revive an independent Bulgarian Church which first roused Bulgarian nationalist sentiment. In 1870 a Bulgarian Exarchate was created by a Sultan edict, and the first Bulgarian Exarch (Antim I) became the natural leader of the emerging nation. The Constantinople Patriarch reacted by excommunicating the Bulgarian Exarchate, which reinforced their will for independence.

In April 1876 the Bulgarians revolted in the so-called April Uprising. The revolt was poorly organized and started before the planned date. It was largely confined to the region of Plovdiv, though certain districts in northern Bulgaria, in Macedonia and in the area of Sliven also took part in it. The uprising was crushed with cruelty by the Ottomans who also brought irregular Ottoman troops (bashi-bazouks) from outside the area. Countless villages were pillages and tens of thousands of people were massacred, the majority of them in the insurgents towns of Batak, Perushtitsa and Bratsigovo in the area of Plovdiv. The massacres aroused a broad public reaction led by liberal Europeans such as William Gladstone, who launched a campaign against the "Bulgarian Horrors". The campaign was supported by a number of European intellectuals and public figures. The strongest reaction, however, came from Russia. The enormous public outcry which the April Uprising had caused in Europe gave the Russians a long-waited chance to realise their long-term objectives with regard to the Ottoman Empire.

Having its reputation at stake, Russia had no other choice but to declare war on the Ottomans in April 1877. The Romanian army and a small contingent of Bulgarian exiles also fought alongside the advancing Russians. The Coalition was able to inflict a decisive defeat on the Ottomans at the Battle of Shipka and at the Pleven, and, by January 1878 they had liberated much of the Bulgarian lands.

Independent Bulgaria

The Treaty of San Stefano of March 3, 1878 provided for an independent Bulgarian state, which spanned over the geographical regions of Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia. However, trying to preserve the balance of power in Europe and fearing the establishment of a large Russian client state on the Balkans, the other Great Powers were reluctant to agree to the treaty.

As a result, the Treaty of Berlin (1878), under the supervision of Otto von Bismarck of Germany and Benjamin Disraeli of Britain, revised the earlier treaty, and scaled back the proposed Bulgarian state. An autonomous Principality of Bulgaria was created, between the Danube and the Stara Planina range, with its seat at the old Bulgarian capital of Veliko Turnovo, and including Sofia. This state was to be under nominal Ottoman sovereignty but was to be ruled by a prince elected by a congress of Bulgarian notables and approved by the Powers. They insisted that the Prince could not be a Russian, but in a compromise Prince Alexander of Battenberg, a nephew of Tsar Alexander II, was chosen. An autonomous Ottoman province under the name of Eastern Rumelia was created south of the Stara Planina range. The Bulgarians in Macedonia and Eastern Trace were left under the rule of the Sultan. Some Bulgarian territories were also given to Serbia and Romania.

Communist Bulgaria

During this time (1944-1989), the country was known as the "People's Republic of Bulgaria" (PRB) and was ruled by the Bulgarian Communist Party (BCP). BCP transformed itself in 1990, changing its name to "Bulgarian Socialist Party", and is currently part of the governing coalition government.

Although Dimitrov had been in exile, mostly in the Soviet Union, since 1923, he was far from being a Soviet puppet. He had shown great courage in Nazi Germany during the Reichstag Fire trial of 1933, and had later headed the Comintern during the period of the Popular Front. He was also close to the Yugoslav Communist leader Tito, and believed that Yugoslavia and Bulgaria, as closely related South Slav peoples, should form a federation. This idea was not favoured by Stalin, and there have long been suspicions that Dimitrov's sudden death in July 1949 was not accidental, although this has never been proved. It coincided with Stalin's expulsion of Tito from the Cominform, and was followed by a "Titoist" witchhunt in Bulgaria. This culminated in the show trial and execution of the Deputy Prime Minister, Traicho Kostov. The elderly Kolarov died in 1950, and power then passed to an extreme Stalinist, Vulko Chervenkov.

Bulgaria's Stalinist phase lasted less than five years. Agriculture was collectivised and peasant rebellions crushed. Labor camps were set up and at the height of the repression housed about 100,000 people. The Orthodox Patriarch was confined to a monastery and the Church placed under state control. In 1950 diplomatic relations with the U.S. were broken off. The Turkish minority was persecuted, and border disputes with Greece and Yugoslavia revived. The country lived in a state of fear and isolation. But Chervenkov's support base even in the Communist Party was too narrow for him to survive long once his patron, Stalin, was gone. Stalin died in March 1953, and in March 1954 Chervenkov was deposed as Party Secretary with the approval of the new leadership in Moscow and replaced by Todor Zhivkov. Chervenkov stayed on as Prime Minister until April 1956, when he was finally dismissed and replaced by Anton Yugov.

History after 1989

By the time the impact of Mikhail Gorbachev's reform program in the Soviet Union was felt in Bulgaria in the late 1980s, the Communists, like their leader, had grown too feeble to resist the demand for change for long. In November 1989 demonstrations on ecological issues were staged in Sofia, and these soon broadened into a general campaign for political reform. The Communists reacted by deposing the decrepit Zhivkov and replacing him with Petur Mladenov, but this gained them only a short respite. In February 1990 the Party voluntarily gave up its claim on power and in June 1990 the first free elections since 1931 were held, won by the moderate wing of the Communist Party, renamed the Bulgarian Socialist Party. In July 1991 a new Constitution was adopted, in which there was a weak elected President and a Prime Minister accountable to the legislature.

Like the other post-Communist regimes in eastern Europe, Bulgaria found the transition to capitalism more painful than expected. The anti-Communist Union of Democratic Forces (UDF) took office and between 1992 and 1994 carried through the privatisation of land and industry through the issue of shares in government enterprises to all citizens, but these were accompanied by massive unemployment as uncompetitive industries failed and the backward state of Bulgaria's industry and infrastructure were revealed. The Socialists portrayed themselves as the defender of the poor against the excesses of the free market. The reaction against economic reform allowed Zhan Videnov of the BSP to take office in 1995. But by 1996 the BSP government was also in difficulties, and in the presidential elections of that year the UDF's Petur Stoyanov was elected. In 1997 the BSP government collapsed and the UDF came to power. Unemployment, however, remained high and the electorate became increasingly dissatisfied with both parties.

See also

- List of Bulgarian monarchs

- Bulgarians

- Bulgarian Orthodox Church

- History of the Balkans

- History of Europe

References

- Balkans : A history of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Rumania, Turkey / by Nevill Forbes ... [et al.]. 1915.

- History of Bulgaria / Hristo Hristov ; [translated from the Bulgarian, Stefan Kostov ; editor, Dimiter Markovski]. Khristov, Khristo Angelov,. c1985.

- History of Bulgaria, 1393-1885 / [by] Mercia Macdermott. MacDermott, Mercia, 1927- [1962].

- Concise history of Bulgaria / R.J. Crampton. Crampton, R. J. 1997.

- Short history of Bulgaria / [by] D. Kossev, H. Hristov [and] D. Angelov ; [Translated by Marguerite Alexieva and Nicolai Koledarov ; illustrated by Ivan Bogdanov [and] Vladislav Paskalev]. Kossev, D. 1963.

- Short history of Bulgaria / Nikolai Todorov ; [L. Dimitrova, translator]. Todorov, Nikolai, 1921- 1975.

- 12 Myths in Bulgarian History/ [by] Bozhidar Dimitrov; Published by "KOM Foundation," Sofia, 2005.

- The 7th Ancient Civilizations in Bulgaria [The Golden Prehistoric Civilization, Civilization of Thracians and Macedonians, Hellenistic Civilization, Roman [Empire] Civilization, Byzantine [Empire] Civilization, Bulgarian Civilization, Islamic Civilization]]/ [by] Bozhidar Dimitrov; Published by "KOM Foundation," Sofia, 2005 (108 p.)