Robert Browning

Robert Browning | |

|---|---|

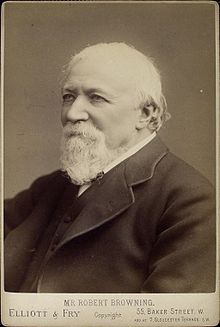

Robert Browning during his later years | |

| Born | 7 May 1812 Camberwell, London, England |

| Died | 12 December 1889 (aged 77) Venice, Italy |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Notable works | The Ring and the Book, Men and Women, The Pied Piper of Hamelin, Porphyria's Lover, My Last Duchess |

| Signature | |

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose mastery of dramatic verse, especially dramatic monologues, made him one of the foremost Victorian poets.

Biography

Early years

Robert Browning was born in Camberwell – a district now forming part of the borough of Southwark in South London, England – the only son of Sarah Anna (née Wiedemann) and Robert Browning.[1][2] His father was a well-paid clerk for the Bank of England, earning about £150 per year.[3] Browning’s paternal grandfather was a wealthy slave owner in Saint Kitts, West Indies, but Browning's father was an abolitionist. Browning's father had been sent to the West Indies to work on a sugar plantation, but revolted by the slavery there, he returned to England. Browning’s mother was a daughter of a German shipowner who had settled in Dundee, and his Scottish wife. Browning had one sister, Sarianna. Browning's paternal grandmother, Margaret Tittle, who had inherited a plantation in St Kitts, was rumoured within the family to have had some Jamaican mixed race ancestry. Author Julia Markus suggests St Kitts rather than Jamaica.[4][5] There is little evidence to support this rumour, and it seems to be merely an anecdotal family story.[6] Robert's father, a literary collector, amassed a library of around 6,000 books, many of them rare. Thus, Robert was raised in a household of significant literary resources. His mother, to whom he was very close, was a devout nonconformist and a talented musician.[1] His younger sister, Sarianna, also gifted, became her brother's companion in his later years, after the death of his wife in 1861. His father encouraged his children's interest in literature and the arts.[1]

By twelve, Browning had written a book of poetry which he later destroyed when no publisher could be found. After being at one or two private schools, and showing an insuperable dislike to school life, he was educated at home by a tutor via the resources of his father's extensive library.[1] By the age of fourteen he was fluent in French, Greek, Italian and Latin. He became a great admirer of the Romantic poets, especially Shelley. Following the precedent of Shelley, Browning became an atheist and vegetarian, both of which he gave up later. At the age of sixteen, he studied Greek at University College London but left after his first year.[1] His parents' staunch evangelical faith prevented his studying at either Oxford University or Cambridge University, both then open only to members of the Church of England.[1] He had inherited substantial musical ability through his mother, and composed arrangements of various songs. He refused a formal career and ignored his parents' remonstrations, dedicating himself to poetry. He stayed at home until the age of 34, financially dependent on his family until his marriage. His father sponsored the publication of his son's poems.[1]

First published works

In March 1833, Pauline, a fragment of a confession was published anonymously by Saunders and Otley at the expense of the author, the costs of printing having been borne by an aunt, Mrs Silverthorne.[7] It is a long poem composed in homage to Shelley and somewhat in his style. Originally Browning considered Pauline as the first of a series written by different aspects of himself, but he soon abandoned this idea. The press noticed the publication. W.J. Fox writing in the The Monthly Repository of April 1833 discerned merit in the work. Allan Cunningham praised it in the The Athenaeum. Some years later, probably in 1850, Dante Gabriel Rossetti came across it in the Reading Room of the British Museum and wrote to Browning, then in Florence to ask if he was the author.[8] John Stuart Mill, however, wrote that the author suffered from an "intense and morbid self-consciousness".[9] Later Browning was rather embarrassed by the work, and only included it in his collected poems of 1868 after making substantial changes and adding a preface in which he asked for indulgence for a boyish work.[8]

In 1834 he accompanied the Chevalier George de Benkhausen, the Russian consul-general, on a brief visit to St Petersburg and began Paracelsus, which was published in 1835.[10] The subject of the 16th century savant and alchemist was probably suggested to him by the Comte Amédée de Ripart-Monclar, to whom it was dedicated. The publication had some commercial and critical success, being noticed by Wordsworth, Dickens, Landor, J.S. Mill and others, including Tennyson (already famous). It is a monodrama without action, dealing with the problems confronting an intellectual trying to find his role in society. It gained him access to the London literary world.

As a result of his new contacts he met Macready, who invited him to write a play.[10] Strafford was performed five times. Browning then wrote two other plays, one of which was not performed, while the other failed, Browning having fallen out with Macready.

In 1838 he visited Italy, looking for background for Sordello, a long poem in heroic couplets, presented as the imaginary biography of the Mantuan bard spoken of by Dante in the Divine Comedy, canto 6 of Purgatory, set against a background of hate and conflict during the Guelph-Ghibelline wars. This was published in 1840 and met with widespread derision, gaining him the reputation of wanton carelessness and obscurity. Tennyson commented that he only understood the first and last lines and Carlyle claimed that his wife had read the poem through and could not tell whether Sordello was a man, a city or a book.[11]

Browning's reputation began to make a partial recovery with the publication, 1841–1846, of Bells and Pomegranates, a series of eight pamphlets, originally intended just to include his plays. Fortunately his publisher, Moxon, persuaded him to include some "dramatic lyrics", some of which had already appeared in periodicals.[10]

Marriage

In 1845, Browning met the poet Elizabeth Barrett, six years his elder, who lived as a semi-invalid in her father's house in Wimpole Street, London. They began regularly corresponding and gradually a romance developed between them, leading to their marriage and journey to Italy (for Elizabeth's health) on 12 September 1846.[12][13] The marriage was initially secret because Elizabeth's domineering father disapproved of marriage for any of his children. Mr. Barrett disinherited Elizabeth, as he did for each of his children who married: “The Mrs. Browning of popular imagination was a sweet, innocent young woman who suffered endless cruelties at the hands of a tyrannical papa but who nonetheless had the good fortune to fall in love with a dashing and handsome poet named Robert Browning. ”[14] At her husband's insistence, the second edition of Elizabeth’s Poems included her love sonnets. The book increased her popularity and high critical regard, cementing her position as an eminent Victorian poet. Upon William Wordsworth's death in 1850, she was a serious contender to become Poet Laureate, the position eventually going to Tennyson.

From the time of their marriage and until Elizabeth's death, the Brownings lived in Italy, residing first in Pisa, and then, within a year, finding an apartment in Florence at Casa Guidi (now a museum to their memory).[12] Their only child, Robert Wiedemann Barrett Browning, nicknamed "Penini" or "Pen", was born in 1849.[12] In these years Browning was fascinated by, and learned from, the art and atmosphere of Italy. He would, in later life, describe Italy as his university. As Elizabeth had inherited money of her own, the couple were reasonably comfortable in Italy, and their relationship together was happy. However, the literary assault on Browning's work did not let up and he was critically dismissed further, by patrician writers such as Charles Kingsley, for the desertion of England for foreign lands.[12]

Major works

In Florence, probably from early in 1853, Browning worked on the poems that eventually comprised his two-volume Men and Women, for which he is now well known;[12] in 1855, however, when these were published, they made relatively little impact.

Elizabeth died in 1861: Robert Browning returned to London the following year with Pen, by then 12 years old, and made their home in 17 Warwick Crescent, Maida Vale. It was only when he returned to England and became part of the London literary scene—albeit while paying frequent visits to Italy (though never again to Florence)—that his reputation started to take off.[12]

In 1868, after five years work, he completed and published the long blank-verse poem The Ring and the Book. Based on a convoluted murder-case from 1690s Rome, the poem is composed of twelve books, essentially ten lengthy dramatic monologues narrated by the various characters in the story, showing their individual perspectives on events, bookended by an introduction and conclusion by Browning himself. Long, even by Browning's own standards (over twenty thousand lines), The Ring and the Book was the poet's most ambitious project and arguably his greatest work; it has been praised as a tour de force of dramatic poetry.[15] Published separately in four volumes from November 1868 through to February 1869, the poem was a success both commercially and critically, and finally brought Browning the renown he had sought for nearly forty years.[15] The Robert Browning Society was formed in 1881 and his work was recognised as belonging within the British literary canon.[15]

Last years and death

In the remaining years of his life Browning travelled extensively. After a series of long poems published in the early 1870s, of which Balaustion's Adventure and Red Cotton Night-Cap Country were the best-received.[15] The volume Pacchiarotto, and How He Worked in Distemper included an attack against Browning's critics, especially Alfred Austin, later to become Poet Laureate. According to some reports Browning became romantically involved with Louisa, Lady Ashburton, but he refused her proposal of marriage, and did not re-marry. In 1878, he revisited Italy for the first time in the seventeen years since Elizabeth's death, and returned there on several further occasions. In 1887, Browning produced the major work of his later years, Parleyings with Certain People of Importance In Their Day. It finally presented the poet speaking in his own voice, engaging in a series of dialogues with long-forgotten figures of literary, artistic, and philosophic history. The Victorian public was baffled by this, and Browning returned to the brief, concise lyric for his last volume, Asolando (1889), published on the day of his death.[15]

Browning died at his son's home Ca' Rezzonico in Venice on 12 December 1889.[15] He was buried in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey; his grave now lies immediately adjacent to that of Alfred Tennyson.[15]

Browning was awarded many distinctions. He was made LL.D. of Edinburgh, a life Governor of London University, and had the offer of the Lord Rectorship of Glasgow. But he turned down anything that involved public speaking.

Poetic style

This article possibly contains original research. (September 2011) |

Browning is often known by some of his short poems, such as Porphyria's Lover, My Last Duchess,Rabbi Ben Ezra, How they brought the good News From Ghent to Aix, Evelyn Hope, The Pied Piper of Hamelin, A Grammarian's Funeral, A Death in the Desert. Initially, Browning was not regarded as a great poet, since his subjects were often recondite and lay beyond the ken and sympathy of the great bulk of readers; and owing, partly to the subtle links connecting the ideas and partly to his often extremely condensed and rugged expression, the treatment of theme was often difficult and obscure.

Browning’s fame today rests mainly on his dramatic monologues, in which the words not only convey setting and action but also reveal the speaker’s character. Unlike a soliloquy, the meaning in a Browning dramatic monologue is not what the speaker directly reveals but what he inadvertently "gives away" about himself in the process of rationalising past actions, or "special-pleading" his case to a silent auditor in the poem. Rather than thinking out loud, the character composes a self-defence which the reader, as "juror," is challenged to see through. Browning chooses some of the most debased, extreme and even criminally psychotic characters, no doubt for the challenge of building a sympathetic case for a character who does not deserve one and to cause the reader to squirm at the temptation to acquit a character who may be a homicidal psychopath. One of his more sensational dramatic monologues is Porphyria's Lover.

Yet it is by carefully reading the far more sophisticated and cultivated rhetoric of the aristocratic and civilized Duke of My Last Duchess, perhaps the most frequently cited example of the poet's dramatic monologue form, that the attentive reader discovers the most horrific example of a mind totally mad despite its eloquence in expressing itself. The duchess, we learn, was murdered not because of infidelity, not because of a lack of gratitude for her position, and not, finally, because of the simple pleasures she took in common everyday occurrences. She is reduced to an objet d'art in the Duke's collection of paintings and statues because the Duke equates his instructing her to behave like a duchess with "stooping," an action of which his megalomaniac pride is incapable. In other monologues, such as Fra Lippo Lippi, Browning takes an ostensibly unsavory or immoral character and challenges us to discover the goodness, or life-affirming qualities, that often put the speaker's contemporaneous judges to shame. In The Ring and the Book Browning writes an epic-length poem in which he justifies the ways of God to humanity through twelve extended blank verse monologues spoken by the principals in a trial about a murder. These monologues greatly influenced many later poets, including T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, high modernists, the latter singling out in his Cantos Browning's convoluted psychological poem Sordello about a frustrated 13th-century troubadour, as the poem he must work to distance himself from. These concerns reflected Victorian society in the late 19th century.

But he remains too much the prophet-poet for the conceits, puns, and verbal play of the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. His is a modern sensibility, all too aware of the arguments against the vulnerable position of one of his simple characters, who recites: "God's in His Heaven; All's right with the world." Browning endorses such a position because he sees an immanent deity that, far from remaining in a transcendent heaven, is indivisible from temporal process, assuring that in the fullness of theological time there is ample cause for celebrating life.

History of sound recording

At a dinner party on 7 April 1889, at the home of Browning's friend the artist Rudolf Lehmann, an Edison cylinder phonograph recording was made on a white wax cylinder by Edison's British representative, George Gouraud. In the recording, which still exists, Browning recites part of "How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix" (and can be heard apologising when he forgets the words).[16] When the recording was played in 1890 on the anniversary of his death, at a gathering of his admirers, it was said to be the first time anyone's voice "had been heard from beyond the grave."[17][18]

Legacy and cultural references

In his introduction to the Oxford University Press edition of Browning's poems 1833–1864[19] Ian Jack comments that Thomas Hardy, Rudyard Kipling, Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot "all learned from Browning's exploration of the possibilities of dramatic poetry and of colloquial idiom".

In 1914, American modern composer Charles Ives created one of his most innovative and captivating pieces ever, and named it after Browning. It is the Robert Browning Overture, a densely, darkly dramatic piece with gloomy, stark overtones strongly reminiscent of the Second Viennese School.

In 1930 the story of Browning and his wife Elizabeth was made into a play The Barretts of Wimpole Street, by Rudolph Besier. The play was a success and brought popular fame to the couple in the United States. The role of Elizabeth became a signature role for the actress Katharine Cornell. It was twice adapted into film. It was also the basis of the stage musical Robert and Elizabeth, with music by Ron Grainer and book and lyrics by Ronald Millar.

In The Browning Version (Terence Rattigan's 1948 play or one of several film adaptations), a pupil makes a parting present to his teacher of an inscribed copy of Robert Browning's translation of The Agamemnon of Aeschylus.

Stephen King's The Dark Tower was chiefly inspired by the poem "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came" by Robert Browning, whose full text was included in the final volume's appendix.

A memorial plaque on the site of his London home, Warwick Crescent, was unveiled on 11 December 1993.[20]

Browning Close in Royston, Hertfordshire, is named after Robert Browning.

Complete list of works

Followed by a quote from Robert Browning's Epilogue to Asolando.

One who never turned her back but marched breast forward, Never doubted clouds would break, Never dreamed, though right were worsted. wrong would triumph, Held we fall to rise, are baffled to fight better,

Sleep to wake

- Pauline: A Fragment of a Confession (1833)

- Paracelsus (1835)

- Strafford (play) (1837)

- Sordello (1840)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. I: Pippa Passes (play) (1841)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. II: King Victor and King Charles (play) (1842)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. III: Dramatic Lyrics (1842)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. IV: The Return of the Druses (play) (1843)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. V: A Blot in the 'Scutcheon (play) (1843)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. VI: Colombe's Birthday (play) (1844)

- Bells and Pomegranates No. VII: Dramatic Romances and Lyrics (1845)

- "The Laboratory"

- "How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix"

- "The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed's Church"

- "The Lost Leader"

- "Home Thoughts from Abroad"

- Bells and Pomegranates No. VIII: Luria and A Soul's Tragedy (plays) (1846)

- Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day (1850)

- Men and Women (1855)

- "Love Among the Ruins"

- "The Last Ride Together"

- "A Toccata of Galuppi's"

- "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came"

- "Fra Lippo Lippi"

- "Andrea Del Sarto"

- "The Patriot/ An Old Story"

- "A Grammarian's Funeral"

- "An Epistle Containing the Strange Medical Experience of Karshish, the Arab Physician"

- Dramatis Personae (1864)

- The Ring and the Book (1868–9)

- Balaustion's Adventure (1871)

- Prince Hohenstiel-Schwangau, Saviour of Society (1871)

- Fifine at the Fair (1872)

- Red Cotton Night-Cap Country, or, Turf and Towers (1873)

- Aristophanes' Apology (1875)

- The Inn Album (1875)

- Pacchiarotto, and How He Worked in Distemper (1876)

- The Agamemnon of Aeschylus (1877)

- La Saisiaz and The Two Poets of Croisic (1878)

- Dramatic Idylls (1879)

- Dramatic Idylls: Second Series (1880)

- Jocoseria (1883)

- Ferishtah's Fancies (1884)

- Parleyings with Certain People of Importance In Their Day (1887)

- Asolando (1889)

- Prospice

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Browning, Robert. Ed. Karlin, Daniel (2004) Selected Poems Penguin p9

- ^ http://www.bookrags.com/biography/robert-browning-dlb2/

- ^ John Maynard, Browning's Youth

- ^ Ebony Magazine May 1995, p95 "Dared and Done"

- ^ Dared and done: the marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning Knopf, 1995, University of Michigan p112 ISBN 9780679416029

- ^ The dramatic imagination of Robert Browning: a literary life (2007) Richard S. Kennedy, Donald S. Hair, University of Missouri Press p7 ISBN 0-8262-1691-9

- ^ Chesterton, G K (1951 (first edition 1903)). Robert Browning. London: Macmillan Interactive Publishing. ISBN 978-0333021187.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "III". The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 volumes. Vol. XIII. 1907–21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Stevenson, Sarah. "Robert Browning". Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Ian Jack, ed. (1970). "Introduction and Chronology". Browning Poetical Works 1833–1864. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019254165.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Browning, Robert. Ed. Karlin, Daniel (2004) Selected Poems Penguin

- ^ a b c d e f Browning, Robert. Ed. Karlin, Daniel (2004) Selected Poems Penguin p10

- ^ Poets.org profile

- ^ Peterson, William S. Sonnets From The Portuguese. Massachusetts: Barre Publishing, 1977.

- ^ a b c d e f g Browning, Robert. Ed. Karlin, Daniel (2004) Selected Poems Penguin p11

- ^ Poetry Archive, retrieved May 2, 2009

- ^ Kreilkamp, Ivan, "Voice and the Victorian storyteller." Cambridge University Press, 2005, page 190. ISBN 0-521-85193-9, ISBN 978-0-521-85193-0. Retrieved May 2, 2009

- ^ "The Author," Volume 3, January–December 1891. Boston: The Writer Publishing Company. "Personal gossip about the writers-Browning." Page 8. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Browning (1970). "Introduction". In Ian Jack (ed.). Browning Poetical Works 1833–1864. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019254165.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ City of Westminster green plaques http://www.westminster.gov.uk/services/leisureandculture/greenplaques/

Further reading

- Anonymous (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day. Illustrated by Waddy, Frederick. London: Tinsley Brothers. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- Berdoe, Edward. The Browning Cyclopædia. 3rd Ed. (Swan Sonnenschein, 1897)

- Chesterton, G.K. Robert Browning (Macmillan, 1903)

- DeVane, William Clyde. A Browning handbook. 2nd. Ed. (Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1955)

- Drew, Philip. The poetry of Robert Browning: A critical introduction. (Methuen, 1970)

- Finlayson, Iain. Browning: A Private Life. (HarperCollins, 2004)

- Garrett, Martin ed., Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning: Interviews and Recollections. (Macmillan, 2000)

- Garrett, Martin. Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning. (British Library Writers' Lives). (British Library, 2001)

- Hudson, Gertrude Reese. Robert Browning's literary life from first work to masterpiece. (Texas, 1992)

- Karlin, Daniel. The courtship of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett. (Oxford, 1985)

- Kelley, Philip et al. (Eds.) The Brownings' correspondence. 20 vols. to date. (Wedgestone, 1984–) (Complete letters of Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning to 1854.)

- Litzinger, Boyd and Smalley, Donald (eds.) Robert Browning: the Critical Heritage. (Routledge, 1995)

- Markus, Julia. Dared and Done: the Marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning (Bloomsbury, 1995)

- Maynard, John. Browning's youth. (Harvard Univ. Press, 1977)

- Ryals, Clyde de L. The Life of Robert Browning: a Critical Biography. (Blackwell, 1993)

- Woolford, John and Karlin, Daniel. Robert Browning. (Longman, 1996)

External links

- Profile and poems written and audio at the Poetry Archive

- Profile and poems at the Poetry Foundation

- Profile and poems at Poets.org

- The Brownings: A Research Guide (Baylor University)

- The Browning Letters Project (Baylor University)

- The Browning Collection at Balliol College, University of Oxford

- The Browning Society

- Works by Robert Browning at Project Gutenberg

- Template:Worldcat id

- Works by Robert Browning in e-book

- An analysis of "Home Thoughts, From Abroad"

- Browning archive at the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin

- Works by Robert Browning, from the Internet Archive

- The British Library – Robert Browning read by Robert Hardy and Greg Wise Hear audio recordings of Browning's poetry with accompanying biography and discussion