African elephant

| African elephant[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

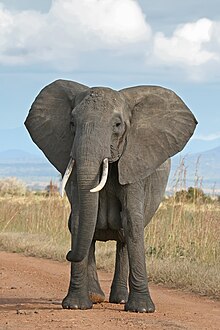

| African bush elephant, Loxodonta africana in Mikumi National Park, Tanzania | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | Loxodonta Anonymous, 1827 |

| Species | |

| |

| Distribution of Loxodonta (2007) | |

African elephants are the elephants of the genus Loxodonta (Greek for 'oblique-sided tooth'[2]), consisting of two extant species: the African bush elephant and the smaller African forest elephant. Loxodonta is one of the two existing genera in the family Elephantidae. Although it is commonly believed that the genus was named by Georges Cuvier in 1825, Cuvier spelled it "Loxodonte". An anonymous author romanized the spelling to "Loxodonta", and the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) recognizes this as the proper authority.[1]

Fossil members of Loxodonta have only been found in Africa, where they developed in hey ya people middle Pliocene.

Description

One of the species of African elephant, the bush elephant, is the largest living terrestrial animal, while the forest elephant is the third largest. Their thickset bodies rest on stocky legs, and they have concave backs.[3] Their large ears enable heat loss.[4] The upper lip and nose form a trunk. The trunk acts as a fifth limb, a sound amplifier and an important method of touch. African elephants' trunks end in two opposing lips,[5] whereas the Asian elephant trunk ends in a single lip.[5] In L. africana, males stand 3.2–4.0 m (10–13 ft) tall at the shoulder and weigh 4,700–6,048 kg (10,360–13,330 lb), while females stand 2.2–2.6 m (7–9 ft) tall and weigh 2,160–3,232 kg (4,762–7,125 lb);[6] L. cyclotis is smaller with male shoulder heights of up to 2.5 m (8 ft).[7]

The largest recorded individual stood Template:Convert/spell to the shoulders and weighed 10 tonnes (10 long tons; 11 short tons).[3]

Teeth

Elephants have four molars; each weighs about 5 kg (11 lb) and measures about 30 cm (12 in) long. As the front pair wears down and drops out in pieces, the back pair shifts forward, and two new molars emerge in the back of the mouth. Elephants replace their teeth six times. At about 40 to 60 years of age, the elephant no longer has teeth and will likely die of starvation, a common cause of death. The enamel plates of the molars are fewer in number than in Asian elephants.[8]

Their tusks are firm teeth; the second set of incisors become the tusks. They are used for digging for roots and stripping the bark off trees for food, for fighting each other during mating season, and for defending themselves against predators. The tusks weigh from 23–45 kg (51–99 lb) and can be from 1.5–2.4 m (5–8 ft) long. Unlike Asian elephants, both male and female African elephants have tusks.[9] They are curved forward and continue to grow throughout the elephant's lifetime.[5]

Distribution and habitat

African elephants can be found in Eastern, Southern and West Africa,[10] either in dense forests, mopane and miombo woodlands, Sahelian scrub or deserts.[4]

Classification

- African bush elephant, Loxodonta africana[1]

- North African elephant, Loxodonta africana pharaoensis (extinct). Presumed subspecies north of the Sahara from the Atlas to Ethiopia.

- African forest elephant, Loxodonta cyclotis[1]

- Loxodonta atlantica (fossil). Presumed ancestor of the modern African elephants

- Loxodonta exoptata (fossil). Presumed ancestor of L. atlantica[2]

- ?Loxodonta adaurora (fossil). May belong in Mammuthus.

Bush and forest elephants were formerly considered subspecies[11] of the same species Loxodonta africana. As described in the entry for the forest elephant in the third edition of Mammal Species of the World (MSW3),[12] there is now morphological and genetic evidence they should be considered as separate species.[13][14][15]

Note the shorter and wider head of L. cyclotis, with a concave instead of convex forehead.

Much of the evidence cited in MSW3 is morphological. The African forest elephant has a longer and narrower mandible, rounder ears, a different number of toenails, straighter and downward tusks, and considerably smaller size. With regard to the number of toenails: the African bush elephant normally has four toenails on the front foot and three on the hind feet, the African forest elephant normally has five toenails on the front foot and four on the hind foot (like the Asian elephant), but hybrids between the two species commonly occur.

MSW3 lists the two forms as full species[1] and does not list any subspecies in its entry for Loxodonta africana.[16] However, this approach is not taken by the United Nations Environment Programme's World Conservation Monitoring Centre nor by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), both of which list L. cyclotis as a synonym (not even a subspecies) of L.africana.[17][18]

A consequence of the IUCN taking this view is that the IUCN Red List makes no independent assessment of the conservation status of the two forms of African elephant. It merely assesses the two forms taken together, as a unit, as vulnerable.[17]

A study of nuclear DNA sequences published in 2010 indicated that the divergence date between forest and savanna elephants is 2.6–5.6 million years ago, which is virtually the same as the divergence date estimated between the Asian elephant and woolly mammoths (2.5–5.4 million years ago), strongly supporting their status as separate species. Forest elephants were found to have a high degree of genetic diversity, perhaps reflecting periodic fragmentation of their habitat during the climatic changes of the Pleistocene.[14]

Behavior

African elephant societies are arranged around family units. Each family unit is made up of around ten closely related females and their calves and is led by an old female known as the matriarch.[3] When separate family units bond, they form kinship groups or bond groups. After puberty, male elephants tend to form alliances with other males.

Elephants are at their most fertile between the ages of 25 and 45.[3] Calves are born after a gestation period of nearly two years. They are cared for by their mother and other young females in the group, known as allomothers.[3]

Elephants use some vocalisations that are beyond the hearing range of humans, to communicate across large distances. Elephant mating rituals include the gentle entwining of trunks.[19] The following sequence of five images was shot in the Addo Elephant Park in South Africa

Feeding

African elephants can eat up to 450 kilograms (992 lb) of vegetation per day, although their digestive system is not very efficient; only 40 percent of this food is properly digested.[20] They use their trunk to pluck at leaves and their tusks to tear at branches, which can cause enormous damage.[5]

Intelligence

African elephants are highly intelligent,[21] and they have a very large and highly convoluted neocortex, a trait also shared by humans, apes and certain dolphin species. They are amongst the world's most intelligent species. With a mass of just over 5 kg (11 lb), elephant brains are larger than those of any other land animal, and although the largest whales have body masses twenty-fold those of a typical elephant, whale brains are barely twice the mass of an elephant's brain. The elephant's brain is similar to that of humans in terms of structure and complexity - such as the elephant's cortex having as many neurons as a human brain,[22] suggesting convergent evolution.[23]

Elephants exhibit a wide variety of behaviors, including those associated with grief, learning, allomothering, mimicry, art, play, a sense of humor, altruism, use of tools, compassion, cooperation,[24] self-awareness, memory and possibly language.[25] All point to a highly intelligent species that is thought to be equal with cetaceans[26][27][28][29] and primates.[27][30]

Conservation

Poaching and population estimates

Poaching significantly reduced the population of Loxodonta in certain regions during the 20th century. In the ten years preceding an international ban in the trade in ivory in 1990 the African elephant population was more than halved from 1.3 million to around 600,000.[31][32] An example of how the ivory trade causes poaching pressure is in the eastern region of Chad. There, the estimated elephant population was 400,000 as recently as 1970, but by 2006 the number had dwindled to about 10,000.

Additionally, the magnitude of poaching during 2006-2012 has been large, including some 3,000 elephants slaughtered during the three-year period 2006-2009 (an average of some 3 elephants killed per day during the period), some 650 elephants poached in February 2012 over the course of a few days in Bouba N'Djida park in Cameroon, and at least 86 elephants including 33 pregnant females killed in Chad in less than a week in early March 2013 in "a potentially devastating blow to one of central Africa's last remaining elephant populations."[33]

Legal protections and conservation status

The African elephant nominally has governmental protection, but poaching for the ivory trade can devastate populations.[34] Kenya was one of the worst affected countries with populations declining by as much as 85 percent between 1973 and 1989.[10]

Protection of African elephants has become high profile in many countries. In 1989, the Kenyan Wildlife Service burnt a stockpile of tusks in protest against the ivory trade.[35] A number of states permit sport hunting of elephants.[5] In 2012, The New York Times reported on a large upsurge in ivory poaching, with about 70% flowing to China.[36]

A major issue in elephant conservation is the conflicts between elephants and a growing human population.[10] Human encroachment into or adjacent to natural areas where bush elephants occur has led to recent research into methods of safely driving groups of elephants away from humans, including the discovery that playback of the recorded sounds of angry honey bees is remarkably effective at prompting elephants to flee an area.[37] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) African elephant specialist group has set up a human elephant conflict working group to look at conserving a species that has potential to be detrimental to human populations. They believe that different approaches are needed in different countries and regions, and so develop conservation strategies at National and Regional levels.[38]

Under the auspices of the Convention on Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), also known as the Bonn Convention, the Memorandum of Understanding concerning Conservation Measures for the West African Populations of the African Elephant was concluded and came into effect on 22 November 2005. The MoU aims to protect the West African Elephant populations by providing an international framework for range State governments, scientists and conservation groups to collaborate in the conservation of the species and its habitat.

References

This article incorporates text from the ARKive fact-file "African elephant" under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License and the GFDL.

- ^ a b c d e Shoshani, J. (2005). "Genus Loxodonta". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Kalb, Jon E. (1993). Fossil Elephantoids from the Hominid-Bearing Awash Group, Middle Awash Valley, Afar Depression, Ethiopia. Independence Square, Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. pp. 52–59. ISBN 0-87169-831-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Macdonald, D (2001). The New Encyclopedia of Mammals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ a b c d e Burnie, D. (2001). Animal. London: Dorling Kindersley.

- ^ Laurson, Barry and Bekoff, Marc (6 Jan 1978). "Loxodonta africana" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 92: 1–8. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Forest elephant videos, photos and facts - Loxodonta cyclotis". ARKive. Retrieved 2012-07-23.

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. p. 208. ISBN 0-521-34697-5.

- ^ Asian Elephant. Denver Zoo

- ^ a b c Blanc, J.J.; Thouless, C.R.; Hart, J.A. (2003). African Elephant Status Report 2002: An update from the African Elephant Database (PDF). IUCN, Gland and Cambridge.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Estes, Richard D. (1999). The Safari Companion. Chelsea Green Publishing Company. p. 223. ISBN 1-890132-44-6.

- ^ Shoshani, J. (2005). "Loxodonta cyclotis". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Rohland, Nadin; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Pollack, Joshua L.; Slatkin, Montgomery; Matheus, Paul; Hofreiter, Michael (2007). "Proboscidean Mitogenomics: Chronology and Mode of Elephant Evolution Using Mastodon as Outgroup". PLoS Biology. 5 (8): e207. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050207. PMC 1925134. PMID 17676977.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Rohland, Nadin (2010). "Genomic DNA sequences from mastodon and woolly mammoth reveal deep speciation of forest and savanna elephants". PLoS Biology. 8 (12): e1000564. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564. PMC 3006346. PMID 21203580.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Murphy, W. J. (2011). "Reconciling Apparent Conflicts between Mitochondrial and Nuclear Phylogenies in African Elephants". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e20642. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020642. PMC 3110795. PMID 21701575.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Shoshani, J. (2005). "Loxodonta africana". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b Template:IUCN2010

- ^ UNEP-WCMC database entry for ''Loxodonta cyclotis''. Unep-wcmc.org. Retrieved on 2013-06-28.

- ^ Buss, Irven (1966). Observations on Reproduction and Breeding Behavior of the African Elephant (PDF). Allen Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Animals of the Amboseli National Park. amboselinationalpark.co.uk

- ^ Aldous, Peter (2006-10-30). "Elephants see themselves in the mirror". New Scientist. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ Roth, Gerhard. "Is the human brain unique?". Mirror Neurons and the Evolution of Brain and Language. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 63–76. doi:10.1002/0470867221.ch2. ISBN 9780470849606.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Goodman, M.; Sterner, K.; Islam, M.; Uddin, M.; Sherwood, C.; Hof, P.; Hou, Z.; Lipovich, L.; Jia, H. (19 November 2009). "Phylogenomic analyses reveal convergent patterns of adaptive evolution in elephant and human ancestries". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (49): 20824–20829. doi:10.1073/pnas.0911239106. PMC 2791620. PMID 19926857.

- ^ "Elephants know when they need a helping trunk in a cooperative task". PNAS. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ^ Parsell, D.L. (2003-02-21). "In Africa, Decoding the "Language" of Elephants". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Viegas, Jennifer (2011). "Elephants smart as chimps, dolphins". ABC Science. Retrieved 2011-03-08.

- ^ a b Viegas, Jennifer (2011). "Elephants Outwit Humans During Intelligence Test". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "What Makes Dolphins So Smart?". The Ultimate Guide: Dolphins. 1999. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ "Mind, memory and feelings". Friends Of The Elephant. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Scott, David (2007-10-19). "Elephants Really Don't Forget". Daily Express. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ "To Save An Elephant" by Allan Thornton & Dave Currey, Doubleday 1991 ISBN 0-385-40111-6

- ^ "A System of Extinction - the African Elephant Disaster" Environmental Investigation Agency 1989

- ^ 86 elephants killed in Chad poaching massacre. Guardian (2013-03-19). Retrieved on 2013-06-28.

- ^ Goudarzi, Sara (2006-08-30). "100 Slaughtered Elephants Found in Africa". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-31.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Poole, Joyce (1996). Coming of Age With Elephants. New York: Hyperion. p. 232. ISBN 0-7868-6095-2.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Gettleman, Jeffrey (September 3, 2012). "Elephants Dying in Epic Frenzy as Ivory Fuels Wars and Profits". The New York Times.

- ^ King, Lucy E.; Douglas-Hamilton, Iain; Vollrath, Fritz (2007). "African elephants run from the sound of disturbed bees". Current Biology. 17 (19): R832–3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.038. PMID 17925207.

- ^ "IUCN African Elephant Specialist Group". 2006-02. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

External links

- African elephant media from ARKive

- CMS West African Elephant Memorandum of Understanding

- Elephant Information Repository - An in-depth resource on elephants

- "Elephant caves" of Mt Elgon National Park

- ElephantVoices - Resource on elephant vocal communications

- Amboseli Trust for Elephants - Interactive web site

- David Quammen: " Family ties - The elephants of Samburu" National Geographic Magazine September 2008 link

- EIA 25 yrs investigating the ivory trade, reports etc

- EIA (in the USA) reports etc

- International Elephant Foundation