West Wycombe Park

WE F the public during the summer months and a venue for civil weddings and corporate entertainment, which help to fund its maintenance and upkeep.

Architecture

Ethos

West Wycombe Park, architecturally inspired by the villas of the Veneto constructed during the late renaissance period, is not one of the largest, grandest or best-known of England's many country houses. Compared to its Palladian contemporaries, such as Holkham Hall, Woburn Abbey and Ragley Hall, it is quite small, yet it is architecturally important as it encapsulates a period of 18th century English social history, when young men, known as dilettanti, returning from the nearly obligatory Grand Tour with newly purchased acquisitions of art, often built a country house to accommodate their new collections and display in stone the learning and cultivation they had acquired during their travels.[2]

The West Wycombe estate was acquired by Sir Francis Dashwood, 1st Baronet and his brother Samuel in 1698. Dashwood demolished the existing manor house and built a modern mansion on higher ground nearby. This mansion forms the core of the present house. Images of the house on early estate plans show a quite conventional square house in the contemporary late Carolean style. In 1724, Dashwood bequeathed this unremarkable house to his 16-year-old son, the 2nd Baronet, also Francis, later Lord le Despencer, who is perhaps best known for establishing the Hellfire Club close to the mansion, in the West Wycombe Caves. Two years later, he embarked on a series of Grand Tours: the ideas and manners he learned during this period influenced him throughout his life and were pivotal in the rebuilding of his father's simple house, transforming it into the classical edifice that exists today.

West Wycombe has been described as "one of the most theatrical and Italianate mid-18th century buildings in England".[3] Of all the country houses of the 18th century, its façades replicate in undiluted form not only the classical villas of Italy on which Palladianism was founded, but also the temples of antiquity on which Neoclassicism was based. The Greek Doric of the house's west portico is the earliest example of the Greek revival in Britain.

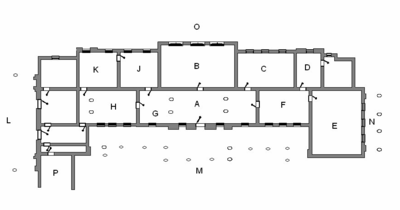

The late 18th century was also a period of change in the interior design of English country houses. The Baroque conception of the principal floor, or piano nobile, with a large bedroom suite known as the state apartments and only one large hall or saloon for common use, was gradually abandoned in favour of smaller, more comfortable bedrooms on the upper floors. This revised floor plan allowed the principal floor to become a series of reception rooms, each with a designated purpose, creating separate areas such as the withdrawing room, dining room, music room, and ballroom. In this way, West Wycombe perfectly reflects the changes and ideals of the late 18th century. This arrangement of reception and public rooms on a lower floor, with bedrooms and more private rooms above, survives unchanged.

Exterior

The builder of West Wycombe, Sir Francis Dashwood, 2nd Baronet, employed three different architects and two landscape architects in the design of the house and its grounds. He also had a huge input himself: he had made the Grand Tour, seen the villas of the Italian renaissance first hand, and wished to emulate them.

Work began in 1740 and finished c.1800, when the older house had been fully transformed inside and out. This long building time explains the flaws and variations in design: when building commenced in 1740, Palladianism was the height of fashion, but, by the time of its completion, Palladianism had been completely succeeded by Neoclassicism; thus, the house is a marriage of both styles. While the marriage is not completely unhappy, the Palladian features are marred by the lack of Palladio's proportions: the east portico is asymmetrical with the axis of the house, and trees were planted either side to draw the eye away from the design flaw.

The finest architects of the day submitted plans to transform the older family house into a modern architectural extravaganza. Among them was Robert Adam, who submitted a plan for the west portico, but his idea was dropped;[4] finally, the architect Nicholas Revett was consulted and created the present west portico. Today, the first sight of the house as one approaches from the drive is this large west portico: from this direction, the entire end of the house appears as a Grecian temple. This eight-columned portico, inspired by the Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek and completed by 1770, is considered to be the earliest example of Greek revival architecture in Britain.[5] The opposite (east) end of the house, designed by John Donowell and completed c.1755, appears equally temple-like, but this time the muse was the Villa Rotunda. Thus the two opposing porticos, east and west, illustrate perfectly the period of architectural transformation of the late 18th century from the earlier Roman inspired Palladian architecture to the more Greek inspired Neoclassicism.

The principal façade is the great south front, a two-storey colonnade of Corinthian columns superimposed on Tuscan, the whole surmounted by a pediment in the centre. The columns are not stone, but wood coated in stucco. This is particularly interesting, as cost was no object in the construction of the house. The architect of this elevation was John Donowell, who executed the work between 1761 and 1763 (although he had to wait until 1775 for payment[6]). The façade, which has similarities to the main façade of Palladio's Palazzo Chiericati of 1550, was originally the entrance front. The front door is still in the centre of the ground floor leading into the main entry hall. This in itself is a substantial deviation from the classical form: West Wycombe does not have a first floor piano nobile: had the architect truly followed Palladio's ideals, the main entrance and principal rooms would have been on the first floor reached by an outer staircase, giving the main reception rooms elevated views, and allowing the ground floor to be given over to service rooms.

The more severe north front is of 11 bays, with the end bays given significance by rustication at ground floor level. The centre of this façade has Ionic columns supporting a pediment and originally had the Dashwood coat of arms. This façade is thought to date from around 1750–1751, although the segmented windows of this facade suggest it was one of the first of the 2nd Baronet's improvements to the original house to be completed, as the curved or segmented window heads are symbolic of the earlier part of the 18th century.[7]

Interior

The principal reception rooms are on the ground floor with large sash windows opening immediately into the porticos and the colonnades, and therefore onto the gardens, a situation unheard of in the grand villas and palaces of Renaissance Italy. The mansion contains a series of 18th century salons decorated and furnished in the style of that period, with polychrome marble floors, and painted ceilings depicting classical scenes of Greek and Roman mythology. Of particular note is the entrance hall, which resembles a Roman atrium with marbled columns and a painted ceiling copied from Robert Wood's Ruins of Palmyra.

Many of the reception rooms have painted ceilings copied from Italian palazzi, most notably from the Palazzo Farnese in Rome. The largest room in the house is the Music Room, which opens onto the east portico. The ceiling fresco in this room depicts the "Banquet of the Gods" and was copied from the Villa Farnesina. The Saloon, which occupies the centre of the north front, contains many marbles, including statuettes of the four seasons. The ceiling depicting "The Council of the Gods and the Admission of Psyche" is also a copy from Villa Farnesina.

The Dining Room walls are painted faux jasper and hold paintings of the house's patron — Sir Francis Dashwood — and his fellow members of the Divan Club (a society for those who had visited the Ottoman Empire). The room also has a painted ceiling from Wood's Palmyra.

The Blue Drawing Room is dominated by the elaborate painted ceiling depicting "The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne" (illustrated left). This room houses a plaster statuette of the Venus de' Medici and marks the 2nd Baronet's risqué devotion to that goddess of love. The room has walls of blue flock hung in the 1960s bearing paintings from various Italian schools of the 17th century.

The relatively small study contains plans for the house and potential impressions for various elevations. One is reputed to have been drawn by Sir Francis Dashwood himself, while the Tapestry Room, once ante-room to the adjoining former principal bedroom, is hung with tapestries given to the 1st Duke of Marlborough to celebrate his victories in the Low Countries. Marlborough was a distant kinsman of the Dashwoods. The tapestries, woven c.1710, depicting peasant scenes by Teniers, have been cut and adapted to fit the proportions and features of the room.

In spite of the grandeur of the interior decoration, the interior of the house is not overpowering. The rooms are not cavernously large nor the ceilings gigantically high. The many large windows in each room allow light to flood in illuminating the colours of the many paintings, silk hangings on the walls and antique furniture.

The gardens and the Park

The gardens at West Wycombe Park are among the finest and most idiosyncratic 18th century gardens surviving in England.[8] The park is unique in its consistent use of Classical architecture from both Greece and Italy. The two principal architects of the gardens at West Wycombe were John Donowell and Nicholas Revett. They designed all of the ornamental buildings in the park. The landscape architect Thomas Cook began to execute the plans for the park, with a nine-acre man-made lake created from the nearby River Wye in the form of a swan. The lake originally had a Spanish galleon for the amusement of Dashwood's guests, complete with a resident captain on board.[9] Water leaves the lake down a cascade and into a canal pond.

One of the most important landmarks in the late Georgian period was the introduction of many new species of trees and flora from around the world, which Horace Walpole described as giving the "richness and colouring so peculiar to the modern landscape".[10] The new species also allowed changes of mood through changes of planting, so an area could be dark and melancholic, or light and ebullient, or mysterious; thus, contemporary gardens such as West Wycombe and Stourhead, both arranged as a walk around a lake, took the visitor through a range of locations, each with its own specific character and quite separate from the last. Humphry Repton later extended the 5,000 acres (20 km²) of grounds to the east, towards the nearby town of High Wycombe, until they appeared much as they do today.

The park still contains many follies and temples. The "Temple of Music" is on an island in the lake, inspired by the Temple of Vesta in Rome. It was designed for Dashwood's fêtes champêtres,[11] with the temple used as a theatre; the remains of the stage survive.[12] Opposite the temple is the garden's main cascade which has statues of two water nymphs. The present cascade has been remade, as the original was demolished in the 1830s. An octagonal tower known as the "Temple of the Winds" is based in design on the Tower of the Winds in Athens.[13]

Classical architecture continues along the path around the lake, with the "Temple of Flora", a hidden summerhouse, and the "Temple of Daphne", both reminiscent of a small temple on the Acropolis. Another hidden temple, the "Round Temple", has a curved loggia. Nearer the house, screening the service wing from view, is a Roman triumphal arch, the "Temple of Apollo", also known (because of its former use a venue for cock fighting) as 'Cockpit Arch', which holds a copy of the famed Apollo Belvedere. Close by is the "Temple of Diana", with a small niche containing a statue of the goddess. Another goddess is celebrated in the "Temple of Venus". Below this is an Exedra, a grotto (known as Venus's Parlour) and a statue of Mercury. This once held a copy of the Venus de' Medici; it was demolished in the 1820s but has recently been reconstructed and now holds a replica of the Venus de Milo.

Later structures that break the classical theme include the Gothic style boathouse, a Gothic Alcove — now a romantic ruin hidden amongst undergrowth — and a Gothic Chapel, once home of the village cobbler but later used as the estate kennels. A monument dedicated to Queen Elizabeth II was erected on her 60th birthday in 1986.

The Dashwoods of West Wycombe

Sir Francis Dashwood built West Wycombe to entertain, and there has been much speculation on the kind of entertainment he provided for his guests. Judged against the sexual morals of the late 18th century, Dashwood and his clique were regarded as promiscuous; while it is likely that the contemporary reports of the bacchanalian orgies over which Dashwood presided in the Hellfire caves above West Wycombe were exaggerated, free love and heavy drinking did take place there.[15] Dashwood often had himself depicted in portraits in fancy dress (in one, dressed as the pope toasting a female Herme[15]), and it is his love of fancy dress which seems to have pervaded through to his parties at West Wycombe Park. Following the dedication of the West portico as a bacchanalian temple in 1771, Dashwood and his friends dressed in skins adorned with vine leaves and went to party by the lake for "Paeans and libations".[16] On another occasion, during a mock sea battle on the lake, the "captain" of one of the yachts masquerading as a battle ship was nearly killed when he was struck by a cannon ball of wadding fired at him from an opposing ship. Dashwood seems to have mellowed in his later years and devoted his life to charitable works. He died in 1781, bequeathing West Wycombe to his half-brother Sir John Dashwood-King, 3rd Baronet.

Dashwood-King spent little time at West Wycombe. On his death in 1793, the estate was inherited by his son Sir John Dashwood, 4th Baronet, Member of Parliament for Wycombe and a friend of the Prince of Wales, although their friendship was tested when Sir John accused his wife of an affair with the prince.[17] Like his father, Sir John cared little for West Wycombe and held a five-day sale of West Wycombe's furniture in 1800. In 1806, he was prevented from selling West Wycombe by the trustees of his son, to whom the estate was entailed. He became religious in the last years of his life, holding ostentatiously teetotal parties in the West Wycombe's gardens in aid of the "Friends of Order and Sobriety" — these would have been vastly different from the bacchanalian fêtes given by his uncle in the grounds. In 1847, Sir John was bankrupt and bailiffs possessed the furniture from his home at Halton. He died estranged from his wife and surviving son in 1849.

Sir John was succeeded by his estranged son Sir George Dashwood, 5th Baronet. For the first time since the death of the 2nd Baronet in 1781, West Wycombe became again a favoured residence. However, the estate was heavily in debt and Sir George was forced to sell the unentailed estates, including Halton, which was sold to Lionel de Rothschild for the then huge sum of £54,000 (£ 7.08 million in 2025). The change in the Dashwoods' fortunes allowed for the refurbishment and restoration of West Wycombe. Sir George died childless in 1862, and left his wife, Elizabeth, a life tenancy of the house while the title and ownership passed briefly to his brother and then a nephew. Lady Dashwood's continuing occupation of the house prevented the nephew, Sir Edwin Hare Dashwood, 7th Baronet, an alcoholic sheep farmer in the South Island of New Zealand, from living in the mansion until she died in 1889, leaving a neglected and crumbling estate.

The 7th Baronet's son, Sir Edwin Dashwood, 8th Baronet, arrived from New Zealand to claim the house, only to find Lady Dashwood's heirs claiming the house's contents and family jewellery, which they subsequently sold. As a consequence, Sir Edwin was forced to mortgage the house and estate in 1892. He died suddenly the following year, and the heavily indebted estate passed to his brother, Sir Robert Dashwood, 9th Baronet. Sir Robert embarked on a costly legal case against the executors of Lady Dashwood, which he lost, and raised money by denuding the estate's woodlands and selling the family town house in London. On his death in 1908, the house passed to his 13-year-old son Sir John Dashwood, 10th Baronet, who in his adulthood sold much of the remaining original furnishings (including the state bed, for £58 — this important item of the house's history complete with its gilded pineapples is now lost). In 1922, he attempted to sell the house itself. He received only one offer, of £10,000 (£ 689,736 in 2025), so the house was withdrawn from sale. Forced to live in a house he disliked,[19] the village of West Wycombe was sold in its entirety to pay for renovations. Not all these renovations were beneficial: painted 18th century ceilings were overpainted white, and the dining room was divided into service rooms, allowing the large service wing to be abandoned to rot.

A form of salvation for West Wycombe was Sir John's wife: Lady Dashwood, the former Helen Eaton, was a socialite who loved entertaining, and did so in some style at West Wycombe throughout the 1930s. Living a semi-estranged life from her husband, occupying opposite ends of the mansion, she frequently gave "large and stylish"[19] house parties funded by further sales of land from the estate.

During World War II, the house saw service as a depository for the evacuated Wallace Collection and a convalescent home. A troop of gunners occupied the decaying service wing, and the park was used for the inflation of barrage balloons. During this turmoil, the Dashwoods retreated to the upper floor and took in lodgers to pay the bills, albeit very superior lodgers, who included Nancy Mitford and James Lees-Milne.

Lees-Milne was secretary of the Country House Committee of the National Trust, which had a wartime office based at West Wycombe. Sir John, appreciating the historical importance of the house, if not the house itself, gave the property to the National Trust in 1943, together with an endowment of £2,000 (£ 113,609 in 2025).

West Wycombe in the 21st century

Today, West Wycombe Park serves a combined role of public museum, family home, and film set. During the summer months, the paying public can tour the ground floor room to view the architecture and the antique contents of the house still owned by the Dashwoods, many of which have been re-purchased and restored to the house by Sir Francis Dashwood, 11th Baronet, in the late 20th century, following their dispersal during the various sales of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The present head of the Dashwood family, Sir Edward Dashwood (born 1964), lives in the mansion with his wife and three young children. Sir Edward runs the estate and house as a commercial concern, in order that the entire estate can be retained and maintained. The house is frequently let out as a filming location, and, in addition to agricultural enterprises, there is a large pheasant shoot with paying guns. Sir Edward is the president of West Wycombe Park Polo Club who have grounds on the estate.

West Wycombe is not just maintained today, but continues to be improved. For example, a huge equestrian sculpture has been installed as the focal point of a long tree lined vista from the house. On close inspection, it proves to be a fibre glass prop found at Pinewood Studios, acquired in the late 20th century by Sir Francis Dashwood (11th Baronet) who paid for it with 12 bottles of champagne.[20] The local Planning Authority was furious but lost their action to have it removed. Today, from a distance, it has been "known to fool experts".[21] The grounds of the park feature in the CBBC TV series, Hounded, starring Rufus Hound. They appear as 'The Park' where the time-travelling Rufus receives instructions from his future self.

The park, a natural amphitheatre,[22] is often the setting for large public concerts and firework displays. In this way, the mansion, often used for weddings and corporate entertainment, and its park are still the setting for the lavish entertaining that their creator planned. In the stewardship of both the National Trust and Sir Edward Dashwood, West Wycombe Park is not only a well-preserved monument to the tastes and foibles of the late 18th century but also a much-used public venue.

See also

- List of garden structures at West Wycombe Park

- List of films shot at West Wycombe Park

- Dashwood baronets

Notes

- ^ Knox p 9.

- ^ Girouard p 177.

- ^ All about Britain.com

- ^ Pevsner p 286 attributes the adjoining, but now semi-demolished, service block and stables to Robert Adam. This attribution is not repeated in other reference books.

- ^ Knox p 7.

- ^ Wallace p 12.

- ^ Pevsner p 283.

- ^ Knox, p30.

- ^ Knox p 4.

- ^ Jackson-Stops, p208.

- ^ Jackson-Stops, p192

- ^ Knox, p37.

- ^ Knox p 36.

- ^ In the background on the hill is the newly completed church, yet curiously the mausoleum constructed c.1764 (by a member of the Bastard family is absent, suggesting the attribution of date to the painting is wrong. If the date 1776 was correct then the lady portrayed is likely to be not Lady Dashwood, who died in 1769, but Frances Barry, Dashwood's mistress and mother of his two children, with whom he lived after the death of his wife.

- ^ a b Knox p 50.

- ^ Jackson-Stops p 148.

- ^ Knox p 57.

- ^ Knowles

- ^ a b Knox p 61.

- ^ Knox p 35.

- ^ Knox p 35. Knox does not name these experts

- ^ Knox p 5

References

- Girouard, Mark (1978). Life in the English country house. Yale: Yale University.

- Jackson-Stops, Gervase (1988). The Country House Garden (A grand tour). London: Pavilion Book Ltd. ISBN 1-85145-123-4.

- Knox, Tim (2001). West Wycombe Park. Bromley, Kent.: The National Trust.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1973). Buckinghamshire. England: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-14-071019-1.

- Wallace, Carew (1967). West Wycombe Park. England: National Trust.

- All about Britain.com Retrieved 18 August 2006

- The di Camillo Companion, database of houses. Retrieved 18 August 2006

- Knowles George. Sir Francis Dashwood Controverscial.Com Retrieved 20 August 2006