RAID

RAID (redundant array of interconneced disks) is a storage technology that combines multiple disk drive components into a logical unit for the purposes of data redundancy and performance improvement. Data is distributed across the drives in one of several ways, referred to as RAID levels, depending on the specific level of redundancy and performance required.

The term "RAID" was first used by David Patterson, Garth A. Gibson, and Randy Katz at the University of California, Berkeley in 1987, standing for redundant array of inexpensive disks.[1] Industry RAID manufacturers later tended to interpret the acronym as standing for redundant array of independent disks.[2][3][4][5]

RAID is now used as an umbrella term for computer data storage schemes that can divide and replicate data among multiple physical drives: RAID is an example of storage virtualization and the array can be accessed by the operating system as one single drive.[note 1] The different schemes or architectures are named by the word RAID followed by a number (e.g. RAID 0, RAID 1). Each scheme provides a different balance between the key goals: reliability and availability, performance and capacity. RAID levels greater than RAID 0 provide protection against unrecoverable (sector) read errors, as well as whole disk failure.

History

Norman Ken Ouchi at IBM was awarded a 1978 U.S. patent 4,092,732[6] titled "System for recovering data stored in failed memory unit." The claims for this patent describe what would later be termed RAID 5 with full stripe writes. This 1978 patent also mentions that drive mirroring or duplexing (what would later be termed RAID 1) and protection with dedicated parity (that would later be termed RAID 4) were prior art at that time.

The term RAID was first defined by David A. Patterson, Garth A. Gibson and Randy Katz at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1987. They studied the possibility of using two or more drives to appear as a single device to the host system and published a paper: "A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks (RAID)" in June 1988 at the SIGMOD conference.[1]

Standard levels

A number of standard schemes have evolved. These are called levels. Originally, there were five RAID levels, but many variations have evolved—notably several nested levels and many non-standard levels (mostly proprietary). RAID levels and their associated data formats are standardized by the Storage Networking Industry Association (SNIA) in the Common RAID Disk Drive Format (DDF) standard:[7][8]

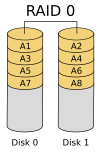

RAID 0

RAID 0 comprises striping (but no parity or mirroring). It improves performance but does not add redundancy and does not improve fault tolerance. Any drive failure destroys the array, and the likelihood of failure increases with more drives in the array.[3]

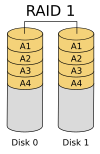

RAID 1

RAID 1 comprises mirroring (without parity or striping). Data is written identically to two (or more) drives, thereby producing a "mirrored set". The read request is serviced by either of the two drives containing the requested data. This can improve performance if data is read from the disk with the least seek latency and rotational latency. Conversely, write performance can be degraded because both drives must be updated; thus the write performance is determined by the slower of the two drives. The array continues to operate as long as at least one drive is functioning.[3]

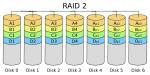

RAID 2

RAID 2 comprises bit-level striping with dedicated Hamming-code parity. All disk spindle rotation is synchronized and data is striped such that each sequential bit is on a different drive. Hamming-code parity is calculated across corresponding bits and stored on at least one parity drive.[3]

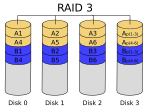

RAID 3

RAID 3 comprises byte-level striping with dedicated parity. All disk spindle rotation is synchronized and data is striped such that each sequential byte is on a different drive. Parity is calculated across corresponding bytes and stored on a dedicated parity drive.[3] Although implementations exist,[9] RAID 3 is not commonly used in practice.

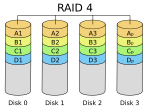

RAID 4

RAID 4 comprises block-level striping with dedicated parity. Parity data is stored on a single dedicated drive.[citation needed]

RAID 4 was previously used primarily by NetApp, but has now been largely replaced by an implementation of RAID 6 (RAID-DP).[10]

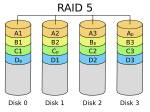

RAID 5

RAID 5 comprises block-level striping with distributed parity. Unlike in RAID 4, parity information is distributed among the drives. It requires that all drives but one be present to operate. Upon failure of a single drive, subsequent reads can be calculated from the distributed parity such that no data is lost. RAID 5 requires at least three disks.[3]

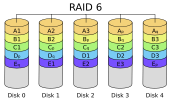

RAID 6

RAID 6 comprises block-level striping with double distributed parity. Double parity provides fault tolerance up to two failed drives. This makes larger RAID groups more practical, especially for high-availability systems, as large-capacity drives take longer to restore. As with RAID 5, a single drive failure results in reduced performance of the entire array until the failed drive has been replaced.[3]

Nested RAID levels (RAID 10, 0+1, 100, 30, 50 and 60)

RAID levels can be nested. See Nested RAID levels.

Comparison

The following table provides an overview of some considerations for standard RAID levels. In each case:

- Array space efficiency is given as an expression in terms of the number of drives, ; this expression designates a fractional value between zero and one, representing the fraction of the sum of the drives' capacities that is available for use. For example, if three drives are arranged in RAID 3, this gives an array space efficiency of thus, if each drive in this example has a capacity of 250 GB, then the array has a total capacity of 750 GB but the capacity that is usable for data storage is only 500 GB.

- Array failure rate is given as an expression in terms of the number of drives, , and the drive failure rate, (which is assumed identical and independent for each drive) and can be seen to be a Bernoulli trial.[citation needed] For example, if each of three drives has a failure rate of 5% over the next three years, and these drives are arranged in RAID 3, then this gives an array failure rate over the next three years of:

| Level | Description | Minimum # of drives[limit 1] | Space efficiency | Fault tolerance | Array failure rate[limit 2] | Read performance | Write performance | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAID 0 | Block-level striping without parity or mirroring | 2 | 1 | 0 (none) | nX | nX |

| |

| RAID 1 | Mirroring without parity or striping | 2 | 1/n | n−1 drives | nX[limit 3] | 1X |

| |

| RAID 2 | Bit-level striping with dedicated Hamming-code parity | 3 | 1 − 1/n ⋅ log2(n-1) | RAID 2 can recover from one drive failure or repair corrupt data or parity when a corrupted bit's corresponding data and parity are good. | (Varies) | (Varies) | (Varies) |

|

| RAID 3 | Byte-level striping with dedicated parity | 3 | 1 − 1/n | 1 drive | (n−1)X | (n−1)X[limit 4] |

| |

| RAID 4 | Block-level striping with dedicated parity | 3 | 1 − 1/n | 1 drive | (n−1)X | (n−1)X[limit 4] |

| |

| RAID 5 | Block-level striping with distributed parity | 3 | 1 − 1/n | 1 drive | (n−1)X[limit 4] | (n−1)X[limit 4] |

| |

| RAID 6 | Block-level striping with double distributed parity | 4 | 1 − 2/n | 2 drives | (n−2)X[limit 4] | (n−2)X[limit 4] |

| |

| RAID 10 | Mirroring without parity, and block-level striping | 4 | 2/n | 1 drive / span[limit 5] | nX | (n/2)X |

| |

| Level | Description | Minimum # of drives[limit 1] | Space efficiency | Fault tolerance | Array failure rate[limit 2] | Read performance | Write performance | Figure |

Limitations

- ^ a b Assumes a non-degenerate minimum number of drives

- ^ a b Assumes independent, identical rate of failure amongst drives

- ^ Theoretical maximum, as low as 1X in practice

- ^ a b c d e f Assumes hardware is fast enough to support

- ^ Raid 10 can only lose one drive per span up to the max of 2/n drives.

Nested (hybrid) RAID

In what was originally termed hybrid RAID,[11] many storage controllers allow RAID levels to be nested. The elements of a RAID may be either individual drives or RAIDs themselves. However, if a RAID is itself an element of a larger RAID, it is unusual for its elements to be themselves RAIDs.

The final RAID is known as the top array. When the top array is a RAID 0 (such as in RAID 1+0 and RAID 5+0), most vendors omit the "+" (yielding RAID 10 and RAID 50, respectively).

- RAID 0+1: striped sets in a mirrored set (minimum four drives; even number of drives) provides fault tolerance and improved performance but increases complexity.

- The key difference from RAID 1+0 is that RAID 0+1 creates a second striped set to mirror a primary striped set. The array continues to operate with one or more drives failed in the same mirror set, but if drives fail on both sides of the mirror the data on the RAID system is lost.

- RAID 1+0: (a.k.a. RAID 10) mirrored sets in a striped set (minimum four drives; even number of drives) provides fault tolerance and improved performance but increases complexity.

- The key difference from RAID 0+1 is that RAID 1+0 creates a striped set from a series of mirrored drives. The array can sustain multiple drive losses so long as no mirror loses all its drives.[12]

RAID parity

Many RAID levels employ an error protection scheme called "parity", a widely used method in information technology to provide fault tolerance in a given set of data. Most use the simple XOR parity described in this section, but RAID 6 uses two separate parities based respectively on addition and multiplication in a particular Galois Field or Reed–Solomon error correction.[13]

Non-standard levels

Many configurations other than the basic numbered RAID levels are possible, and many companies, organizations, and groups have created their own non-standard configurations, in many cases designed to meet the specialized needs of a small niche group. Most non-standard RAID levels are proprietary:

- Linux MD RAID10 (RAID 10) implements a general RAID driver that defaults to a standard RAID 1 with two drives, and a standard RAID 1+0 with four drives, but can have any number of drives, including odd numbers. MD RAID 10 can run striped and mirrored, even with only two drives with the f2 layout (mirroring with striped reads, giving the read performance of RAID 0; normal Linux software RAID 1 does not stripe reads, but can read in parallel).[12][14][15]

- Hadoop has a RAID system that generates a parity file by xor-ing a stripe of blocks in a single HDFS file.[16]

- RAID-F, as implemented in FlexRAID, provides RAID over File System.[17] The RAID engines in that system are all non-standard and have their own nomenclature in the form of Tx, where T stands for Tolerance and x represents the tolerance level. The most acclaimed of them all is the Tx engine providing RAID∞ (infinity) data protection and recovery.[citation needed]

Data backup

A RAID system used as secondary storage is not an alternative to backing up data. In RAID levels > 0, a RAID protects from catastrophic data loss caused by physical damage or errors on a single drive within the array (or two drives in, say, RAID 6). However, a true backup system has other important features such as the ability to restore an earlier version of data, which is needed both to protect against software errors that write unwanted data to secondary storage, and also to recover from user error and malicious data deletion. A RAID can be overwhelmed by catastrophic failure that exceeds its recovery capacity and, of course, the entire array is at risk of physical damage by fire, natural disaster, and human forces, while backups can be stored off-site. A RAID is also vulnerable to controller failure because it is not always possible to migrate a RAID to a new, different controller without data loss.[18]

Implementations

The distribution of data across multiple drives can be managed either by dedicated computer hardware or by software. A software solution may be part of the operating system, or it may be part of the firmware and drivers supplied with a hardware RAID controller.

Software-based RAID

Software RAID implementations are now provided by many operating systems. Software RAID can be implemented as:

- A layer that abstracts multiple devices, thereby providing a single virtual device (e.g. Linux's md)

- A more generic logical volume manager (provided with most server-class operating systems, e.g. Veritas or LVM)

- A component of the file system (e.g. ZFS or Btrfs)

Volume manager support

Server class operating systems typically provide logical volume management, which allows a system to use logical[jargon] volumes that can be resized or moved. Often, features like RAID or snapshots are also supported.

- Vinum is a logical volume manager supporting RAID 0, RAID 1, and RAID 5. Vinum is part of the base distribution of the FreeBSD operating system, and versions exist for NetBSD, OpenBSD, and DragonFly BSD.

- Solaris SVM supports RAID 1 for the boot filesystem, and adds RAID 0 and RAID 5 support (and various nested combinations) for data drives.

- Linux LVM supports RAID 0 and RAID 1.

- HP's OpenVMS provides a form of RAID 1 called "Volume shadowing", giving the possibility to mirror data locally and at remote cluster systems.

File-system support

Some advanced file systems are designed to organize data across multiple storage devices directly (without needing the help of a third-party logical volume manager):

- ZFS supports equivalents of RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 5 (RAID Z), RAID 6 (RAID Z2) and a triple-parity version RAID Z3. As it always stripes over top-level vdevs, it supports equivalents of the 1+0, 5+0, and 6+0 nested RAID levels (as well as striped triple-parity sets) but not other nested combinations. ZFS is the native file system on Solaris and also available on FreeBSD and Linux.[19]

- Btrfs supports RAID 0, RAID 1 and RAID 10 (RAID 5 and 6 are under development).[20][21]

Operating-system support

Many operating systems provide basic RAID functionality independently of volume management:

- Apple's OS X and OS X Server support RAID 0, RAID 1, and RAID 1+0.[22][23]

- FreeBSD supports RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 3, and RAID 5, and all nestings via GEOM modules and ccd.[24][25][26]

- Linux's md supports RAID 0, RAID 1, RAID 4, RAID 5, RAID 6, and all nestings.[27][28] Certain reshaping/resizing/expanding operations are also supported.[29]

- Microsoft's server operating systems support RAID 0, RAID 1, and RAID 5. Some of the Microsoft desktop operating systems support RAID. For example, Windows XP Professional supports RAID level 0, in addition to spanning multiple drives, but only if using dynamic disks and volumes. Windows XP can be modified to support RAID 0, 1, and 5.[30] Windows 8 and Windows Server 2012 introduces a RAID-like feature known as Storage Spaces, which also allows users to specify mirroring, parity, or no redundancy on a folder-by-folder basis.[31]

- NetBSD supports RAID 0, 1, 4, and 5 via its software implementation, named RAIDframe.[32]

Over time, the increase in commodity CPU speed has been consistently greater than the increase in drive throughput;[33] the percentage of host CPU time required to saturate a given number of drives has decreased. For instance, under 100% usage of a single core on a 2.1 GHz Intel "Core2" CPU, the Linux software RAID subsystem (md) as of version 2.6.26 is capable of calculating parity information at 6 GB/s; however, a three-drive RAID 5 array using drives capable of sustaining a write operation at 100 MB/s only requires parity to be calculated at the rate of 200 MB/s, which requires the resources of just over 3% of a single CPU core.

Firmware/driver-based RAID

A RAID implemented at the level of an operating system is not always compatible with the system's boot process, and it is generally impractical for desktop versions of Windows (as described above). However, hardware RAID controllers are expensive and proprietary. To fill this gap, cheap "RAID controllers" were introduced that do not contain a dedicated RAID controller chip, but simply a standard drive controller chip with special firmware and drivers; during early stage bootup, the RAID is implemented by the firmware, and once the operating system has been more completely loaded, then the drivers take over control. Consequently, such controllers may not work when driver support is not available for the host operating system.[34]

Data scrubbing / Patrol read

Data scrubbing involves periodic reading and checking by the RAID controller of all the blocks in a RAID, including those not otherwise accessed. This detects bad blocks before use.[35]

In some environments, documentation refers to data scrubbing as patrol read. Patrol reading checks for bad blocks on each storage device in an array, but also uses the redundancy of the array to recover bad blocks on a single drive and to reassign the recovered data to spare blocks elsewhere on the drive.[36]

RAID with solid-state drives

RAID can provide data security with solid-state drives (SSDs) without the expense of an all-SSD system. For example, a fast SSD can be mirrored with a mechanical drive. For this configuration to provide a significant speed advantage an appropriate controller is needed that uses the fast SSD for all read operations. Adaptec calls this "hybrid RAID",[37] the same term as is sometimes used for nested RAID.

Weaknesses

Correlated failures

In practice, the drives are often the same age (with similar wear) and subject to the same environment. Since many drive failures are due to mechanical issues (which are more likely on older drives), this violates those assumptions; failures are in fact statistically correlated.[3] In practice, the chances of a second failure before the first has been recovered (causing data loss) is not as unlikely as four random failures. In a study of about 100,000 drives, the probability of two drives in the same cluster failing within one hour was four times larger than predicted by the exponential statistical distribution—which characterizes processes in which events occur continuously and independently at a constant average rate. The probability of two failures in the same 10-hour period was twice as large as predicted by an exponential distribution.[38]

A common expectation is that drives designed for server use will fail less frequently than consumer-grade drives usually used in desktop computers. A study by Carnegie Mellon University[39] and an independent one by Google[40] both found that the "grade" of a drive does not relate to the drive's failure rate.

Unrecoverable Read Errors (URE) during rebuild

Unrecoverable Read Errors present as sector read failures. The unrecoverable bit-error (UBE) rate is typically specified at 1 bit in 1015 for enterprise class drives (SCSI, FC, SAS), and 1 bit in 1014 for desktop class drives (IDE/ATA/PATA, SATA). Increasing drive capacities and large RAID 5 redundancy groups have led to an increasing inability to successfully rebuild a RAID group after a drive failure because an unrecoverable sector is found on the remaining drives.[3][41] Parity schemes such as RAID 5 when rebuilding are particularly prone to the effects of UREs as they affect not only the sector where they occur but also reconstructed blocks using that sector for parity computation; typically an URE during a RAID 5 rebuild leads to a complete rebuild failure.[42]

Double protection schemes such as RAID 6 are attempting to address this issue, but suffer from a very high write penalty. Schemes that duplicate (mirror) data such as RAIDs 1 and 10 have a lower risk from UREs than those using parity computation.[43] Background scrubbing can be used to detect and recover from UREs (which are latent and invisibly compensated for dynamically by the RAID controller) as a background process, by reconstruction from the redundant RAID data and then re-writing and re-mapping to a new sector; and so reduce the risk of double-failures to the RAID system.[44][45]

Recovery time is increasing

Drive capacity has grown at a much faster rate than transfer speed, and error rates have only fallen a little in comparison. Therefore, larger capacity drives may take hours, if not days, to rebuild. The re-build time is also limited if the entire array is still in operation at reduced capacity.[46] Given a RAID with only one drive of redundancy (RAIDs 3, 4, and 5), a second failure would cause complete failure of the array. Even though individual drives' mean time between failure (MTBF) have increased over time, this increase has not kept pace with the increased storage capacity of the drives. The time to rebuild the array after a single drive failure, as well as the chance of a second failure during a rebuild, have increased over time.[47] Mirroring schemes such as RAID 10 have a bounded recovery time as they require the copy of a single failed drive, compared with parity schemes such as RAID 6, which require the copy of all blocks of the drives in an array set. Triple parity schemes, or triple mirroring, have been suggested as one approach to improve resilience to an additional drive failure during this large rebuild time.[48]

Atomicity: including parity inconsistency due to system crashes

A system crash or other interruption of a write operation can result in states where the parity is inconsistent with the data due to non-atomicity of the write process, such that the parity cannot be used for recovery in the case of a disk failure (the so-called RAID 5 write hole - see below).[3]

This is a little understood and rarely mentioned failure mode for redundant storage systems that do not utilize transactional features. Database researcher Jim Gray wrote "Update in Place is a Poison Apple" during the early days of relational database commercialization.[49]

RAID write hole

The RAID write hole is a known data corruption issue in older and low-end RAIDs, caused by interrupted destaging of writes to disk.[50]

Write cache reliability

A concern about write cache reliability exists, specifically regarding devices equipped with a write-back cache—a caching system that reports the data as written as soon as it is written to cache, as opposed to the non-volatile medium.[51]

Drive error recovery algorithms

Frequently, a RAID controller is configured to drop a component drive (that is, to assume a component drive has failed) if the drive has been unresponsive for 8 seconds or so; this might cause the array controller to drop a good drive because that drive has not been given enough time to complete its internal error recovery procedure. Consequently, desktop drives can be risky in a RAID, and so-called enterprise class drives limit this error recovery time to reduce risk.[citation needed]

Western Digital's desktop drives used to have a specific fix. A utility called WDTLER.exe limited a drive's error recovery time. The utility enabled TLER (time limited error recovery), which limits the error recovery time to 7 seconds. Around September 2009, Western Digital disabled this feature in their desktop drives (e.g., the Caviar Black line), making such drives unsuitable for use in a RAID.[52]

However, Western Digital enterprise class drives are shipped from the factory with TLER enabled. Similar technologies are used by Seagate, Samsung, and Hitachi. Of course, for non-RAID usage, an enterprise class drive with a short error recovery timeout that cannot be changed is therefore less suitable than a desktop drive.[52]

In late 2010, the Smartmontools program began supporting the configuration of ATA Error Recovery Control, allowing the tool to configure many desktop class hard drives for use in a RAID.[52]

Scenarios other than disk failure

While RAID may protect against physical drive failure, the data are still exposed to operator, software, hardware, and virus destruction. Many studies cite operator fault as the most common source of malfunction,[53] such as a server operator replacing the incorrect drive in a faulty RAID, and disabling the system (even temporarily) in the process.[54]

RAID 5 in enterprise environments

Rebuilding a RAID 5 array after a failure adds stress to all working drives, because every area on every disc marked as "in use" must be read to rebuild the lost redundancy. If drives are close to failure, the stress of rebuilding the array can be enough to cause another drive to fail before the rebuild has been finished, and even more so if the server is still accessing the drives to provide data to clients, users, applications, etc. Even without complete loss of an additional drive during rebuild, an unrecoverable read error (URE) is likely for large arrays, and typically leads to a failed rebuild.[41] Thus, it is during this rebuild of the "missing" drive that the entire RAID 5 array is at risk of a catastrophic failure. The rebuild of an array on a busy and large system can take hours and sometimes days.[41] Therefore, it is not surprising that, when systems must be highly available and highly reliable or fault tolerant, other levels, including RAID 6 or RAID 10, are chosen.[41]

With a RAID 6 array, using drives from multiple sources and manufacturers, it is possible to mitigate most of the problems associated with RAID 5. The larger the drive capacities and the larger the array size, the more important it becomes to choose RAID 6 instead of RAID 5.[41] RAID 10 also minimizes these problems.[43]

In August 2012, Dell posted an advisory against the use of RAID 5 or RAID 50 with high capacity drives and in large arrays.[55]

Software RAID issues

If a boot drive fails, the system has to be sophisticated enough to be able to boot off the remaining drive or drives. For instance, consider a computer being booted from a RAID 1 (mirrored drives); if the first drive in the RAID 1 fails, then a first-stage boot loader might not be sophisticated enough to attempt loading the second-stage boot loader from the second drive as a fallback. The second-stage boot loader for FreeBSD is capable of loading a kernel from a RAID 1.[56]

See also

Notes

- ^ The physical drives are said to be "in a RAID", however the more common, somewhat repetitive parlance is to say that they are "in a RAID array". See RAS syndrome.

References

- ^ a b David A. Patterson, Garth Gibson, and Randy H. Katz: A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks (RAID). University of California Berkeley. 1988. Cite error: The named reference "patterson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Originally referred to as Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks, the concept of RAID was first developed in the late 1980s by Patterson, Gibson, and Katz of the University of California at Berkeley. (The RAID Advisory Board has since substituted the term Inexpensive with Independent.)" Storagecc Area Network Fundamentals; Meeta Gupta; Cisco Press; ISBN 978-1-58705-065-7; Appendix A.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Chen, Peter; Lee, Edward; Gibson, Garth; Katz, Randy; Patterson, David (1994). "RAID: High-Performance, Reliable Secondary Storage". ACM Computing Surveys. 26: 145–185.

- ^ Donald, L. (2003). "MCSA/MCSE 2006 JumpStart Computer and Network Basics" (2nd ed.). Glasgow: SYBEX.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Howe, Denis (ed.). Redundant Arrays of Independent Disks from FOLDOC. Imperial College Department of Computing. Retrieved 2011-11-10.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); External link in|publisher= - ^ US patent 4092732, Norman Ken Ouchi, "System for recovering data stored in failed memory unit", issued 1978-05-30

- ^ "Common RAID Disk Drive Format (DDF) standard". SNIA.org. SNIA. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ^ "SNIA Dictionary". SNIA.org. SNIA. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "FreeBSD Handbook, Chapter 20.5 GEOM: Modular Disk Transformation Framework". Retrieved 2012-12-20.

- ^ White, Jay; Lueth, Chris (May 2010). "RAID-DP:NetApp Implementation of Double Parity RAID for Data Protection. NetApp Technical Report TR-3298". Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- ^ Vijayan, S. (1995). "Dual-Crosshatch Disk Array: A Highly Reliable Hybrid-RAID Architecture". Proceedings of the 1995 International Conference on Parallel Processing: Volume 1. CRC Press. pp. I–146ff. ISBN 0-8493-2615-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Jeffrey B. Layton: "Intro to Nested-RAID: RAID-01 and RAID-10", Linux Magazine, January 6, 2011

- ^ Dawkins, Bill and Jones, Arnold. "Common RAID Disk Data Format Specification" [Storage Networking Industry Association] Colorado Springs, 28 July 2006. Retrieved on 22 February 2011.

- ^ [1], question 4

- ^ "Main Page - Linux-raid". Linux-raid.osdl.org. 2010-08-20. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "Hdfs Raid". Hadoopblog.blogspot.com. 2009-08-28. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ admin (2013-10-01). "What is RAID over File System?". FlexRAID.com. FlexRAID. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ "The RAID Migration Adventure". Retrieved 2010-03-10.

- ^ "ZFS on Linux". Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- ^ "Btrfs Wiki: Feature List". 2012-11-07. Retrieved 2012-11-16.

- ^ "Btrfs Wiki: Changelog". 2012-10-01. Retrieved 2012-11-14.

- ^ "Mac OS X: How to combine RAID sets in Disk Utility". Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "Apple Mac OS X Server File Systems". Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ "FreeBSD System Manager's Manual page for GEOM(8)". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "freebsd-geom mailing list - new class / geom_raid5". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "FreeBSD Kernel Interfaces Manual for CCD(4)". Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "The Software-RAID HOWTO". Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ "RAID setup". Retrieved 2008-11-10. [dead link]

- ^ "RAID setup". Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- ^ "Using Windows XP to Make RAID 5 Happen". Tomshardware.com. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Sinofsky, Steven. "Virtualizing storage for scale, resiliency, and efficiency". Microsoft.

- ^ Metzger, Perry (1999-05-12). "NetBSD 1.4 Release Announcement". NetBSD.org. The NetBSD Foundation. Retrieved 2013-01-30.

- ^ "Rules of Thumb in Data Engineering" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ^ "SATA RAID FAQ - ata Wiki". Ata.wiki.kernel.org. 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2012-08-26.

- ^ Ulf Troppens, Wolfgang Mueller-Friedt, Rainer Erkens, Rainer Wolafka, Nils Haustein. Storage Networks Explained: Basics and Application of Fibre Channel SAN, NAS, ISCSI, InfiniBand and FCoE. John Wiley and Sons, 2009. p.39

- ^ Dell Computers, Background Patrol Read for Dell PowerEdge RAID Controllers, By Drew Habas and John Sieber, Reprinted from Dell Power Solutions, February 2006 http://www.dell.com/downloads/global/power/ps1q06-20050212-Habas.pdf

- ^ "Adaptec Hybrid RAID Solutions" (PDF). Adaptec.com. Adaptec. 2012. Retrieved 2013-09-07.

- ^ Disk Failures in the Real World: What Does an MTTF of 1,000,000 Hours Mean to You? Bianca Schroeder and Garth A. Gibson

- ^ "Everything You Know About Disks Is Wrong". Storagemojo.com. 2007-02-22. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ Eduardo Pinheiro, Wolf-Dietrich Weber and Luiz André Barroso (February 2007). "Failure Trends in a Large Disk Drive Population" (PDF). Google Inc. Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- ^ a b c d e "Why RAID 6 stops working in 2019". ZDNet. 22 February 2010.

- ^ J.L. Hafner, V. Deenadhaylan, K. Rao, and J.A. Tomlin. "Matrix methods for lost data reconstruction in erasure codes. USENIX Conference on File and Storage Technologies, p15-30, Dec. 13-16, 2005.

- ^ a b Scott Lowe (2009-11-16). "How to protect yourself from RAID-related Unrecoverable Read Errors (UREs). Techrepublic". Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- ^ M.Baker, M.Shah, D.S.H. Rosenthal, M.Roussopoulos, P.Maniatis, T.Giuli, and P.Bungale. 'A fresh look at the reliability of long-term digital storage." EuroSys2006, Apr. 2006.

- ^ "L.N. Bairavasundaram, GR Goodson, S. Pasupathy, J.Schindler. "An analysis of latent sector errors in disk drives". Proceedings of SIGMETRICS'07, June 12-16,2007" (PDF).

- ^ Patterson, D., Hennessy, J. (2009). Computer Organization and Design. New York: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers. pp 604-605.

- ^ Newman, Henry (2009-09-17). "RAID's Days May Be Numbered". EnterpriseStorageForum. Retrieved 2010-09-07.

- ^ Adam Leventhal (December 1, 2009). "Triple-Parity RAID and Beyond. ACM Queue, Association of Computing Machinery". Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- ^ Jim Gray: The Transaction Concept: Virtues and Limitations (Invited Paper) VLDB 1981: 144-154

- ^ ""Write hole" in RAID5, RAID6, RAID1, and other arrays". ZAR team. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- ^ "Definition of write-back cache at SNIA dictionary".

- ^ a b c "Error recovery control with smartmontools". Retrieved 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ These studies are: Gray, J (1990), Murphy and Gent (1995), Kuhn (1997), and Enriquez P. (2003).

- ^ Patterson, D., Hennessy, J. (2009), 574.

- ^ Peltoniemi, Mikko (2012-08-07). "New RAID level recommendations from Dell". Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- ^ "FreeBSD Handbook". Chapter 19 GEOM: Modular Disk Transformation Framework. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- "Empirical Measurements of Disk Failure Rates and Error Rates", by Jim Gray and Catharine van Ingen, December 2005

- The mathematics of RAID-6, by H. Peter Anvin