Pennon

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2010) |

A pennon was one of the principal three varieties of flags carried during the Middle Ages (the other two were the banner and the standard).[1] Pennoncells and streamers or pendants are minor varieties of this style of flag. The pennon is a flag resembling the guidon in shape, but only half the size. It does not contain any coat of arms, but only crests, mottos and heraldic and ornamental devices.

Pennon comes from the Latin penna meaning "a wing" or "a feather". It was sometimes pointed, but more generally forked or swallow-tailed at the end. In the 11th century, the pennon was generally square, one end being decorated with the addition of pointed tongues or streamers, somewhat similar to the oriflamme. During the reign of Henry III, the pennon acquired the distinctive swallow-tail, or the single-pointed shape. Another version of the single-pointed pennon was introduced in the 13th century. In shape this was a scalene triangle, obtained by cutting diagonally the vertically oblong banner.

The pennon was a purely personal ensign. It was essentially the flag of the knight bachelor, as apart from the knight banneret, carried by him on his lance, displaying his personal armorial bearings, and set out so that they stood in correct position when he couched his lance for charging. A manuscript of the 16th century (Harl. 2358, "A paper Heraldical book in small Quarto") in the British Museum, which gives detailed particulars as to the size, shape and bearings of the standards, banners, pennons and pennoncells, says "a pennon must be two yards and a half long, made round at the end, and contain the arms of the owner," and warns that "from a standard or streamer a man may flee but not from his banner or pennon bearing his arms." A pennoncell (or penselle) was a diminutive pennon carried by the esquires.[1]

Pennons were also used for any special ceremonial occasion, and more particularly at state funerals. For instance, there were "XII doz. penselles" among the items that figured at the funeral of the Duke of Norfolk in 1554, and in the description of the lord mayor's procession in 1555, it reads "two goodly pennes (state barges) decked with flags and streamers, and a 1000 penselles." Among the items that ran the total cost of the funeral of Oliver Cromwell up to an enormous sum of money, we find mention of 30 dozen of pennoncells a foot long and costing 20 shillings a dozen, and 20 dozen of the same kind of flags at 12 shillings a dozen.[2][3]

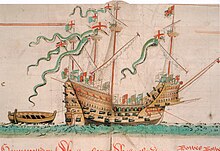

The streamer, so called in Tudor days but now better known as the pennant or pendant, was a long, tapering flag, which it was directed "shall stand in the top of a ship or in the forecastle, and therein be put no arms, but the man's cognisance or device, and may be of length 20, 30, 40 or 60 yards (55 m), and is slit as well as a guidon or standard".[4] Among the fittings of the ship that took Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, to France in the reign of Henry VII was a "great streamer for the ship 40 yards (37 m) in length [and] 8 yards (7.3 m) in breadth".[4]

Besides the white ensign, ships commissioned in the Royal Navy fly a long streamer from the maintopgallant masthead. This, which is called a pennant, is in fact the sign of command, and it is first hoisted when a captain commissions his ship. The pennant, which was really the old "pennoncell", was of three colours for the whole of its length, and towards the end left separate in two or three tails, and so continued until the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Now, however the pennant is a long white streamer with the St George's cross in the inner portion close to the mast. Pennants have been carried by men-of-war from the earliest times, prior to 1653 at the yard-arm, but since that date at the maintopgallant masthead.[5] There are other navies that also fly pennant in a similar manner (see pennant (commissioning)).

The commissioning pennant in ships may end in a point, but they can also be forked, in which case it is also called a banderole.[6]

Pennants are also associated with American sports teams, such as Major League Baseball and college sports teams. In Australian rules football, a pennant is awarded to the winner of major competitions. For many years, this was the only prize given. As a result, a League Championship is often referred to as a "pennant," as in, "The Giants win the Pennant!" And in Australian football, a premiership can also be referred to as a "flag."

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Swinburne 1911, p. 456.

- ^ Swinburne 1911, p. 456,457.

- ^ "For the solemnization of the funeral, no less than the sum of sixty thousand pounds was allotted to defray the expence" (Rutt 1828, pp. 516–530).

- ^ a b Swinburne 1911, p. 458.

- ^ Swinburne 1911, p. 459.

- ^ "1. A long narrow flag, with cleft end, flying from the mast-heads of ships, carried in battle, etc." (OED staff 2011)

References

- OED staff (September 2011). "banderol[e] | bandrol | bannerol, n.". [[Oxford English Dictionary]] (Second 1989; online version September 2011. ed.).

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); URL–wikilink conflict (help) Earlier version first published in New English Dictionary, 1885. - Rutt, John Towill, ed. (1828). "Cromwell's death and funeral order". Diary of Thomas Burton esq, volume 2: April 1657 - February 1658. Institute of Historical Research. pp. 516–530.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Swinburne, H Lawrence (1911). "Flag". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 456–459.