User:Phembree/sandbox

Roger Reynolds | |

|---|---|

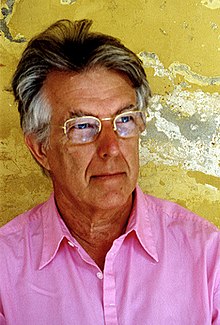

Roger Reynolds in 2005 at Uxmal ruins, Mexico | |

| Background information | |

| Born | July 18, 1934 Detroit, Michigan, United States |

| Genres | Contemporary classical |

| Occupation | Composer |

| Years active | 1957–present |

Roger Reynolds is a Pulitzer-winning American composer.

Roger Reynolds, Pulitzer Prize-winning American composer, was born July 18, 1934 in Detroit, Michigan. He is known for his capacity to integrate diverse ideas and resources, for the seamless blending of traditional musical sounds and those newly enabled by technology[1]. His work responds to text of poetic (Beckett, Borges, Stevens, Ashbery) or mythological (Aeschylus, Euripides) origins. His reputation rests, in part, upon his “wizardry in sending music flying through space: whether vocal, instrumental, or computerized”[2]. This signature feature first appeared in the notationally innovative theater piece, The Emperor of Ice Cream (1961-62)[3].

During his early career, Reynolds worked in Europe and Asia, returning to the US in 1969 to accept an appointment in the music department at the University of California, San Diego. His leadership there established it as a state of the art facility – in parallel with Stanford, IRCAM, and MIT – a center for composition and computer music exploration[4]. He has addressed the tradition with three symphonies, and four string quartets, works that have been performed internationally as well as in North America[5]. Reynolds won early recognition with Fulbright, Guggenheim, NEA, and National Institute of Arts and Letters awards. In 1989, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for a string orchestra composition, Whispers Out of Time, an extended work responding to John Ashbery’s ambitious Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror. Reynolds is author of three books and numerous journal articles. In 2009 he was appointed University Professor, the first artist so honored by University of California[6] . His work has been featured at festivals including Warsaw Autumn, the Proms and Edinburgh Festivals (UK), the Suntory International Series (Tokyo), the Helsinki and Venice biennales. The Library of Congress established a Special Collection of his work in 1998.

His nearly 100 compositions to date are published exclusively by the C.F. Peters Corporation[7], and several dozen CDs and DVDs of his work have been commercially released. Performances by the Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego Symphonies, among others, preceded the most recent large-scale work written in honor of our nation’s first president: george WASHINGTON[8] . This work knits together the Reynolds’s career-long interest in orchestra, text, extended musical forms, intermedia, and computer spatialization of sound[9] .

Reynolds’s work embodies an American artistic idealism reflecting the influence of Varèse and Cage, and has also been compared with that of Boulez[10] and Scelsi. Reynolds lives with his partner of 50 years, Karen, in Del Mar, California, overlooking the Pacific.

Life and work

Beginnings and education (1934–1962)

Early influences: piano studies with Kenneth Aitken (1934–1952)

Roger Reynolds was born on the 18th of July, 1934 in Detroit, Michigan. The seeds for his focus on music were planted almost by accident when his father, an architect, recommended that he purchase some phonograph records. These recordings, including a Vladimir Horowitz performance of Frédéric Chopin's A-flat Polonaise, spurred Reynolds to take up piano lessons with Kenneth Aitken. Aitken demanded that his students delve into the cultural context behind the works of classic keyboard literature they played.[5][13] Around the time that Reynolds graduated from high school in 1952, he performed a solo recital in Detroit that consisted of the Johannes Brahms Sonata in F Minor, some Intermezzi, the sixth Franz Liszt Rhapsody, as well as works by Claude Debussy, and Chopin. Reynolds remembers:

I don't recall public performance as being a particularly enjoyable experience. It served to bring what I cared about in music much closer than did mere phonographic idylls, but I did not, could not feel that what was happening as I played was actually mine. It was not the applause that interested me, but the experience of the music itself.[14]

University of Michigan: Engineering Physics (1952–1957)

Reynolds was uncertain about his prospects as a professional pianist, and entered the University of Michigan to study Engineering Physics, in line with his father's expectations. During what would be his first stint at the University of Michigan, he stayed connected to music and the arts because of the "virtual melting pot of disciplinary aspirations that then engaged him." Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus and James Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man both left marks upon his perception of music and the arts. "I ... consumed [Joyce's Portrait] hungrily, stayed in my dormitory room for weeks, feverish over the allure of its issues, not attending classes and only narrowly escaping academic disaster..." pg. 7[14]

Systems Development Engineer and Military Policeman

After completing his undergraduate, he went to work in the missile industry for Marquardt Ramjet Corporation (Marquardt Corporation). He moved to Van Nuys, near Los Angeles California, and worked as a systems development engineer. However, he quickly found that he was spending an inordinate amount of time practicing piano, and decided to go back to school to study music, with the goal of becoming a small liberal arts college teacher.[15]

But prior to returning to school, Reynolds had a one year obligation as a reservist in the military, which he fulfilled after his short time at Marquardt. As he recalls:

I think that the Army was particularly perverse at that point. Knowing that I was an engineer, I presumed I would have been an Army engineer. But in fact my MSOs (military service obligations) were either light-truck driver or military policeman. So I chose military policeman, and I learned how to disable people and how to be extraordinarily brutal. It was a rather weird experience.[11]

Return to University of Michigan: encounter with Ross Lee Finney

Reynolds returned to Ann Arbor in 1957, prepared to commit himself to life as a pianist. He was quickly diverted from this path upon meeting resident composer Ross Lee Finney, who introduced Reynolds to composition.[5] Reynolds took a composition for non-majors class with Finney, and learned compositional techniques with Finney's graduate assistant. At the end of the semester, Reynold's string trio was performed for the class. According to Reynolds,

Finney just decimated it. ... I mean, everything about it, he destroyed. The sounds, the time, the pitches, the form, everything was wrong. I was chastened.[15]

Despite the harsh introduction, Finney pulled Reynolds aside after the performance and recommended that he study composition over the summer. These summer lessons proved to be brutal. But when Reynolds was nearly ready to quit, at the end of the summer, Finney responded positively to what Reynolds brought in.[15] Reynolds was ensorcelled by composing music, but he was still unsure what it meant to be a composer in America. He recalls that summer:

Although the process was by no means a smooth or an immediately encouraging one, by the time regular classes resumed in the fall of 1960 I was twenty-six, and I knew that I would do everything I could to become a composer. What did that actually mean? I have no recollection now of having had the slightest sense of what the life of a composer in America might involve.[14]

Finney was particularly generous to Reynolds, programming three of his pieces on the Midwest Composers Symposium, which was "unheard of" for student works.[11] At these Midwest Composers Symposia, Reynolds also first encountered Harvey Sollberger, who would become a lifelong colleague and friend.[5] From Finney, Reynolds learned of "the primacy of 'gesture,' which [Reynolds] took to be a composite of rhythm, contour, and physical energy: the empathic resonances that musical ideas could arouse - at root, perhaps, an American tendency to value sensation over analysis."[14]

Composition studies with Roberto Gerhard

Subsequently, when the Spanish expatriate composer Roberto Gerhard came to Ann Arbor, Reynolds gravitated towards him:[5]

I was captivated by the uncommon dimensionality of this man. Not only was he a superb musician and an inventive, even commanding composer of uncluttered, poised, and original music, but he was also both deeply intelligent and emotionally vulnerable. His susceptibility to injury, the outrage he displayed at ethical injustices,the touching warmth he offered from behind a vestigial Spanish crustiness these made an irresistible combination.[11]

From Gerhard, Reynolds absorbed the idea that composition took "the whole man... you must put everything that you have and everything that you are into every musical act. And so where I live, who I interact with, what I hear, what the weather’s like, what my granddaughter says to me, and so on, they all affect the music."[11]

Other early encounters During the later part of his composition studies at the University of Michigan, Reynolds also sought out other encounters with prominent musical personalities, including Milton Babbitt, Edgard Varèse, Nadia Boulanger, John Cage, and Harry Partch.[5] Reynolds sought these composers outside of his academic studies:

It was outside class that I came upon and dug into the implications of Ives, Cage, Varèse and Partch. I sought out the last three and had personal contact with them. Perhaps it was the feeling of, if not exactly forbidden, then certainly "not favored" fruit that caused them to loom so large for me.[11]

Reynolds met with Partch in 1958 in Yellow Springs, Ohio, at Antioch College, where he received the "aphoristic commandment... 'Examine your basic assumptions.'" Reynolds notes that this did not imply abandoning those assumptions.[11]

During 1960, Reynolds met with both Varèse and Cage in New York (and the latter again in 1961 in Ann Arbor), with Babbitt in Ann Arbor in 1960, and with Boulanger in Ann Arbor in 1961.

During this time, Reynolds also composed The Emperor of Ice Cream (1961–1962), which combined aspects of music and theater, and contained many of the features of his later music. It was premiered later in 1965 in Rome.[15]

ONCE festivals 1961–1963

Reynolds co-founded the ONCE Group in Ann Arbor with Robert Ashley and Gordon Mumma, and was active in the first three festivals in 1961 to 1963. Other important figures in these festivals included George Cacioppo, Donald Scavarda, Bruce Wise, filmmaker George Manupelli, and later, ‘Blue’ Gene Tyranny.[16] The ONCE festival was probably the most significant nexus of avant-garde performance art and music in the Midwest in the early 1960s, with programs consisting of both American experimentalism and European modernism.[5] Reynolds recalls:

I think the primary force in the beginning was Bob and Mary Ashley. Bob had been studying at the University of Michigan with Ross Finney. ... [Ashley] had [previously] been at the Manhattan School of Music; he was a pianist at that time. He was very intense and very rebellious in some regards. [Gordon] Mumma had been at Michigan but had dropped out and was working in some kind of research dealing with seismographic measurement... The two of them had become involved with an art professor named Milton Cohen, who had what he called a Space Theatre where he had taken canvas and stretched it to make a circular, tent-like situation and then in the middle there were projectors and mirrors which flashed imagery on the [surrounding] screens. Bob and Gordon had been involved in making electronic music in relation to Cohen’s stuff. ...they realized that if they started a festival, they were going to need resources... I think that I came into the picture partly in that way. ... So there was a confluence of capacity, differential abilities, and common interest.[11]

In 1963, C.F. Peters offered to publish Reynolds's work, a relationship which has been exclusive since that day.[5]

Early career: travels abroad and to California (1962–1969)

Europe: Germany, France and Italy

After he left Ann Arbor the second time, Reynolds traveled throughout Europe with his then partner Karen (later wife), a flutist. They visited France and then Italy on Fulbright, Guggenheim and Rockefeller support. This sojourn to Europe was viewed as a way for Reynolds to find his voice as a composer:[5][13]

The idea was to get out and to have the time to do the kind of growing that I thought I needed to do, because I had composed very few pieces by the time I had graduated from the University of Michigan. So at that time, although it seems odd now, going to Europe was a way of living cheaply. I lived in Europe for almost three years on nothing and with nothing, and that time was spent trying to find myself and my voice.[11]

Reynolds first went to Germany to study with Bernd Alois Zimmermann in Cologne, on a Fulbright Scholarship in 1962/1963.[14] But things did not turn out the way he expected:

I was supposed to study with Zimmermann. I went to his class. And afterwards he took me to coffee and he said, “Look, there’s no point for you to be in this class.” He didn’t say why but he said, “Just do what you want, come back and see me at the end, and I’ll sign off.” So I actually never met with him, never had a lesson with him, never even had a conversation with him.[11]

Instead, Reynolds worked with Gottfried Michael Koenig, and collaborated with Michael von Biel, who was living in the atelier of Karlheinz Stockhausen's friend Mary Bauermeister at that point. Reynolds worked at the West German Radio station's Electronic Music Studio, where he completed A Portrait of Vanzetti (1963)[11]

The following academic year, 1963/1964, Karen received a Fulbright to study in Paris, although ironically one of the most influential moments during that year for Reynolds was in Berlin. Reynolds and Karen traveled there to meet Elliott Carter, and heard his Double Concerto there. Reynolds was particularly struck by the spatial elements in the piece. This influenced his composition Quick Are the Mouths of Earth (1964–1965).[11]

Throughout their years in Europe, despite their lack of funding, Roger and Karen curated several contemporary music concerts in Paris and Italy.[5]

Japan

Reynolds accepted a fellowship from the Institute of Current World Affairs, which took him to Japan from 1966 to 1969. In Japan Reynolds organized the intermedia series CROSS TALK, which in 1969 culminated in a festival at Tangei's Olympic Gymnasium. And met and became close friends with composers Toru Takemitsu, Joji Yuasa, pianist Yuji Takahashi, electronics specialist Junosuke Okuyama, painter Keiji Usami and theatre director Tadashi Suzuki.[5][16]

Reynold's most significant work from his time in Japan was probably PING (1968), a multi-media composition for piano, flute, percussion, harmonium, live electronic sound, film, and visual effects, based on a text by Samuel Beckett.[17] For the work he collaborated with Butoh dancer Sekiji Maro and cinematographer Kazuro Kato, the later of whom previously worked as a cameraman for Akira Kurosawa.[18]

California

Roger and Karen were visiting the Seattle Symphony during 1965 with sponsorship from the Rockefeller Foundation. A trip down the West Coast to visit various university music programs was suggested by the foundation's Arts Officer, Howard Klein. The last stop on that trip was at the quite young University of California, San Diego campus, in La Jolla.[5] The nascent music life at the university was viewed with much promise:

We thought that the most dynamic social scene at that point — this was the late ’60s — was California, and so that’s where we went. But there was not much in San Diego at that time. It was primarily a Navy town. There was a fledgling unit of the University of California ... it was an open playing field, so the possibility of doing things was very great. ... Partch was [also] in San Diego. That wasn’t a reason to go there, but it was certainly an attraction after we got there.[11]

University of California, San Diego (1969–present)

Several years after their visit to La Jolla, Will Ogdon, then UCSD's Department of Music chair, invited the Reynoldses back to the area, offering Reynolds a position as an associate professor. Reynolds began to work on establishing what became the Center for Music Experiment and Related Research in 1971, which later evolved into the Center for Research in Computing and the Arts.[4] In a similar way to the San Francisco Tape Music Center, the initial funding for CME came from the Rockefeller Foundation.[19]

While at UCSD, Reynolds has taught courses on Music Notation, Extended Vocal Techniques, Late Beethoven Works, Text (in relation to the Red Act Project and Greek Drama), Collaboration (co-taught with Steven Schick), Extending Varese (also co-taught with Steven Schick), and the Perils of Large Scale Form (co-taught with Chinary Ung), musical analysis, as well as private and group composition lessons.

After his arrival at the University of California, his interests diverged into several concurrently evolving paths. Thus, it is easier to talk about his work from this point based on common features between works.

Work

Influence of technology

Aside from the traditional instruments of the Western Classical orchestra, Reynolds has worked extensively with analog and digital electronic sound, typically employed to bolster the form and color of his works.[16]

CCRMA

In the late 1970s, John Chowning invited Reynolds to come to Stanford's summer courses at the Center for Computing Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA).[13] Because of the expense of computer equipment, electro-acoustic work was done very differently at that time:

...[W]hen I went to Stanford to start working in computers at the end of the ’70s, I worked with a lot of different people there who were around the lab, because this was at a time when the so-called time-sharing machines meant that everyone in the building heard what everyone else was doing and everyone was involved with everyone else. So if something wasn’t working you just asked the person sitting next to you [for help] and you’d work it out together.[11]

At CCRMA Reynolds finished the sound synthesis portion of ...the Serpent-Snapping Eye (1978)(uses FM Synthesis) and VOICESPACE IV: The Palace (1978–80)(uses digital signal processing).

IRCAM

Shortly after his involvement at CCRMA, the French Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM) offered Reynolds a commission and residency, which was followed up by two more residences over the course of two decades.[5] When he first went to IRCAM, he made the choice to utilize technologically expert assistants to create software or hardware solutions to specific musical ideas inherent in his compositions. This practice has since spawned many collaborative ventures with various musical assistants, as Reynolds notes:[20]

When I went to IRCAM ... there was this concept of the Musical Assistant. ... I realized right away that this allowed me to make a choice: whether I would decide to spend a few years not composing and learning what I would need to do to become a self-sufficient computer-music composer or that I was going to collaborate with other people.

[On collaboration:] You enter into a relationship with one or more people and you have to sacrifice some of your autonomy and they have to sacrifice some of theirs in order to get to a place that you couldn’t get without each other. And I like that kind of situation.

Archipelago (1982–83) was one of the first works that Reynolds did that used technology to drastically alter not only the sounds of the composition, but also the process of composing. The impetus was as the title suggests, a chain of islands, an idea which Reynolds elaborated on with a simultaneous theme and variations process. With fifteen themes and their own variations, distributed unevenly over a thirty-two member chamber orchestra, Reynolds needed technology to transform both the timbres and the order of the sounds in ways that live performers could not.[20] This was the first time that Reynolds spent a great deal of time working with computers to transform musical material, along with spatialization, he used a process "in which [he] was trying to take recognizable kernels and weave them into a mosaic of interacting transformations."[11] IRCAM was an extremely fertile environment for composition, allowing the Archipelago project to thrive:

...[T]he process [of composing the piece] was interactive because I was at IRCAM and had the privilege of working with a very smart young composer, Thierry Lancino, who was my musical assistant, and also consulting with people like David Wessel and Stephen McAdams and so on. It was an astonishing opportunity. But in this case, the tie between the impetus, the medium, and the need for technology was absolutely clear. If one listens to the piece, one hears that [technology] was needed and also that it works.[20]

Odyssey (1989–93), primarily composed during the early 1990s, incorporates two singers, two speakers, instrumental ensemble, and six-channel computer sound. "Odyssey required me to settle on an ideal set of multilingual Beckett texts by means of which to portray the course of his life."[14] There was a chaotic element in the text that Reynolds wished to portray in the music, and he undertook some of the first experiments with using strange attractors (specifically the Lorenz attractor) in music with this composition, citing influence from James Gleick. Reynolds notes that the process of creating musically beguiling results from a strange attractor was "arduous" and "grueling."[14]

His last work at IRCAM, The Angel of Death (2000–01), for solo piano, chamber orchestra, and 6-channel computer processed sound, was written with a substantial number of perceptual psychologists both assisting and analyzing the end results.[5] His assistant on the project was Frederique Voisn, and the principle psychologists were Steven McAdams (IRCAM) and Emannuel Bigand (University of Bourgone). The end results included a special issue of the journal Music Perception, edited by Daniel Levitin, an audio CD / CDROM publication by IRCAM, along with a day-long conference in Sydney, Australia.[21]

UPIC (1983–84)

Shortly after his first trip to IRCAM, he was also invited to compose a work using the Les Atiliers UPIC System, which Iannis Xenakis had created for Mycenae Alpha (1978).[22]

SANCTUARY (2004–10)

A composer-in-residence at the California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology (at UCSD) allowed Reynolds to finish his SANCTUARY project: an evening-length, four-movement piece for percussion quartet and real-time computer transformations. The completed work was premiered in 2007 at I.M. Pei’s National Gallery of Art, and later the same year repeated in the courtyard of the Salk Institute in La Jolla. The DVD that arose from this project was intended to alter the way contemporary classical music is received, because of the intimacy with which the performers knew the work and the audio-visual complexity with which it was presented. Steven Schick and Red Fish Blue Fish had been working on the piece for six years by the time of the DVD was recorded.[15] Ross Karre prepared a complexly scripted editing plan. The embodied experience that such intimacy breeds is very important to Reynolds:

A lot of our experience with music is empathic — that is, we, our bodies, our sensibilities, identify with and respond to, even literally move with the physicality of the sounds that are generating the musical experience. ... [The immersion of the performers in a work] allows our empathy as listeners to flow out and extend and commit. We see that the performers are really engaged and we get engaged; we trust them.[15]

Influence of literature and poetry

Text has been an important resource for Reynolds' work, and since the mid-1970s he has been interested in the use of language as sound, "the ways in which a vocalist's manner of utterance – whether spoken, declaimed, sung, or indebted to some uncommon mode of production" affect the experience of the ideas that the text carries.[14] Reynolds was stimulated by his UCSD colleagues Kenneth Gaburo and baritone Philip Larson, deploying extended vocal techniques, such as "vocal-fry" in the VOICESPACE works (quadraphonic tape compositions): Still (1975), A Merciful Coincidence (1976), Eclipse (1979), and The Palace (1980).[14]

While serving as Valentine Visiting Professor at Amherst College in the late 1980s, Reynolds immersed himself in poetry because of the connection of Amherst with poet Emily Dickinson. He came across John Ashbery's Self-Portrait a Convex Mirror (1974) while reading one evening:

The next morning I realized that things that I had understood the night before I couldn’t understand the next morning. In other words, there was something time specific about comprehension. ... That was very interesting. What usually happens when something like that occurs is that I want to write music about it, and so I decided to do a string orchestra piece.[11]

This string orchestra piece, Whispers Out of Time, was premiered in 1988 in Amherst, and won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1989.[23] Reynolds later worked collaboratively with John Ashbery on the seventy-minute song cycle last things, I think, to think about (1994), which uses a spatialized recording of the poet speaking.

Influence of visual arts

Visual art has provided Reynolds with inspiration for several works, such as the Symphony [The Stages of Life] (1991–92), which drew from self-portraits by Rembrandt and Picasso, and Visions (1991), a string quartet that responded to Bruegel.[5] A later project involving visual art was The Image Machine (2005), which arose from rather elaborate interdisciplinary collaboration called 22, headed by Thanassis Rikakis, then at Arizona State University. This large scale work involved motion capture of a dancer, to be used as a control element:

At the center of this project was the idea that it would be possible to capture the complex motion [of a dancer] in real time, and to have a computer model and then monitor the motion in such a way that it could send control information to other artists who would create parallel and deeply responsive elements to a larger performance totality.[20]

Reynolds worked with choreographer Bill T. Jones, clarinetist Anthony Burr, and percussionist Steven Schick on the project, along with audio software designers Pei Xiang and Peter Otto, and visual rendering artists Paul Kaiser, Shelley Eshkar, and Marc Downie.[20] The process was not necessarily tranquil, though it was rewarding, as Reynolds recalls:

We achieved a meld of media, high technology, and aesthetic force unequaled by anything else I have experienced. The process was not smooth. In fact it was sometimes destructively rancorous. None-the-less, the product of long effort and mutual adjustment, one component resource to the other, showed vividly and thrillingly what one of art's futures might be.[14]

Among the audio software resources created for 22 was MATRIX, a new algorithm designed by Reynolds which he has used since on various projects.[20]

Influence of mythology

Myth has been an important resource for Reynolds's work, as evident in the title of his second symphony: Symphony [Myths] (1990).[5] Later, this mythological preoccupation grew into the Red Act Project, the first installment of which was commissioned by the British Broadcasting Corporation. This piece, the Red Act Arias, was premiered at the 1997 Proms, animating text from Aeschylus with narrator, choir, orchestra and eight channel electronic sound.[5]

Perhaps the most powerful impression any narrative text has ever left on me, though, is that inscribed by Aeschylus in Agamemnon, the first play of the Oresteia trilogy. Again, there is an intersection of intellectual implication, moving narrative, associations through imagery and oppositions that is magnetic. Nevertheless, it is the flow of the language itself as rendered into English by Richmond Lattimore that cemented my resolve to embark upon The Red Act Project. I have been engaged with it for more than a decade.[14]

Responding to related texts, Reynolds produced Justice (2001), commissioned by the Library of Congress, and Illusion (2006), commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic with funding from the Koussevitsky and Rockefeller Foundations.[24]

Space: metaphoric, auditory, architectural

Reynolds has been involved with the concept of Space as a potential musical resource for most of his career, beginning with his theater piece The Emperor of Ice Cream (1961–62).[5] In this work, Reynolds sought to bring conceptual elements in the text to the fore with the aid of spatial movement of sound.

I began my own efforts to address space in modest fashion, in a music-theater composition [The Emperor Ice Cream] intended for the ONCE Festivals but not actually premiered until 1965 in the context of the Nuova Consonanza Festival of Franco Evangelisti's, in Rome. … So, in the case of [Wallace] Stevens's line "And spread it so as to cover her face" the eight singers, arrayed across the front of the stage, pass the phonemes of the associated melodic phrase back and forth by fading in and out successively.[14]

Later, in Japan, Reynolds worked with engineer Junosuke Okuyama to build a "photo-cell sound distributor," which used a matrix of photoelectric cells to move sounds around a quadraphonic setup, with the aid of a flashlight as a kind of controller. This device was used in the multimedia composition Ping (1968).[14] More recently, Reynolds's Mode Records Watershed (1998) DVD was the first such disc to feature music conceived specifically for multi-channel presentation in Dolby Digital 5.1.[13]

I wrote a piece, Watershed IV, for percussionist Steven Schick, which involved the very fundamental conceit that he was centered within an instrumental array. The idea was that the audience would be put in there with him, metaphorically. There would be speakers surrounding the audience that would reproduce, at some level, for the listener, the experience that Steve was having within his array of instruments. Steve and I worked almost a year on the setup for that piece, playing with different spiral arrangements and numbers of instruments and different geometries.[20]

He is concerned not only with the physical locations of sound sources around a listener, but also metaphoric notions of space. As he notes, "'Space' can signify a physical frame work by means of which we comprehend the conditions of the 'real world' around us, but it can also become a referential tool that helps us to place into relative and often revelatory relationships other less objectively characterizable data."[14]

In addition to the auditory effects of spatial location and metaphoric notions of space, Reynolds has responded to various architectural spaces, creating works explicitly for performance in various buildings, including Arata Isozaki's Art Tower Mito and also his Gran Ship, Kenzo Tange's Olympic Gymnasium in Tokyo, Louis I. Kahn's Salk Institute, Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum, Christian de Portzamparc's Cité de la Musique, Frank Gehry's Walt Disney Concert Hall, The Royal Albert Hall, and the Great Hall of the Library of Congress.[5][13] Reynolds adapts his use of spatial audio to the performance space.

Gradually it became clear that blunter tools can work to greater advantage in large spaces with comparatively larger audiences. In composing The Red Act Arias for performance in London's cavernous, 6,000-seat Royal Albert Hall, for example, I decided to use a multileveled system with eight groups of loudspeakers. Rather than attempting to position sounds precisely on perceivable paths around the hall, I concentrated on broad, sweeping gestures that surged across or around the performance space in unmistakable fashion.[14]

Mentorship, research and writing

In addition to his compositional activities, Reynolds's academic career has taken him to Europe, the Nordic countries, South America, Asia and the United States, where he has lectured, organized events, and taught. Though his focus has been on the Music Department at UCSD, Reynolds has occupied visiting positions at various universities: the University of Illinois, Brooklyn College of the CUNY, the Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University, Yale University, Amherst College, and Harvard University. Currently, Reynolds is also Director of an Arts Internship Program at the University of California, Washington Center.

At the University of Illinois, Reynolds wrote his first book, Mind Models: New Forms of Musical Experience (1975). It covers a wide range of topics concerning the contemporary world and the role of art in that world, specific considerations of the materials of music, and the way those materials are shaped by contemporary composers.

At the time that Mind Models first appeared in print, no one else had attempted to rigorously define the issues raised by those composers who broke most deliberately with traditional European practice. ... Reynolds was the first to clearly identify and consolidate into a single framework the vast array of forces (cultural, political, perceptual, and technical) shaping this heterogeneous body of work.[25]

Reynolds wrote A Searcher's Path (1987) while serving as visiting professor at Brooklyn College of the CUNY, and Form and Method: Composing Music while serving as Randolph Rothschild Guest Composer at the Peabody Conservatory of Johns Hopkins University. The later closely details Reynolds's compositional process. In addition to his books, he has written articles for periodicals including Perspectives of New Music, the Contemporary Music Review, Polyphone, Inharmoniques, The Musical Quarterly, Music Perception and Nature.

In addition to visiting positions, Reynolds has also given master classes around the world, in places such as Buenos Aires, Thessaloniki, Porto Alegre, Ircam, Warsaw, and the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki, and the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. Furthermore, he has been a featured composer at numerous music festivals, including Music Today and the Suntory International Program in Japan, the Edinburgh and Proms festivals, the Helsinki and Zagreb biennales, the Darmstadt Courses, New Music Concerts (Toronto), Warsaw Autumn, Why Note? (Dijon), Musica Viva (Munich), the Agora Festival (Paris), various ISCM festivals, and the New York Philharmonic's Horizons.[5]

Notable students

University of California, San Diego

- Mark Applebaum, Associate Professor of Music, Stanford University

- Juan Campoverde

- Benjamin Leeds Carson, Associate Professor of Music, University of California, Santa Cruz

- Chaya Czernowin, Walter Bigelow Rosen Professor of Music, Harvard University

- Paul Dresher

- David Felder, SUNY Distinguished Professor, University at Buffalo

- Larry Groupé, Emmy-winning composer

- Ben Hackbarth, Lecturer of Music at University of Liverpool

- Brenda Hutchinson,

- David Evan Jones, Professor of Music and UCSC Porter College Provost, University of California, Santa Cruz

- Jaroslaw Kapuscinski, Assistant Professor of Composition and Director of Intermedia Performance Lab, Stanford University

- Derek Keller, Assistant Professor of Music, Oberlin College

- Joseph Klein (composer), Distinguished Professor and Chair of the Division of Composition, University of North Texas

- Paul Koonce, Professor of Music, University of Florida; former Assistant Professor, Princeton University

- Olli Kortekangas

- Josh Levine, Assistant Professor of Music, Oberlin College

- Kue-ju Lin

- Andrew May (composer), Associate Professor and Director of CEMI, University of North Texas

- Thanassis Rikakis, Professor and Vice Provost for Design, Arts and Technology, Carnegie Mellon University

- Daniel Tacke, Assistant Professor of Music Theory and Composition, Arkansas State University

- Steven Takasugi, Associate of the Music Department, Harvard University

- Michael Theodore, Associate Professor of Music Composition and Technology, University of Colorado Boulder

- Christopher Tonkin, Head of Composition Studies and Music Technology, University of Western Australia

- Erik Ulman, Lecturer, Stanford University

- Nicolas Vérin, Professor of Music, Ecole Nationale de Musique et de Danse d’Évry

- Rolf Wallin

Yale (while visiting professor)

- Michael Daugherty, Professor of Composition, University of Michigan

- Michael Gordon (composer), Faculty member, NYU Steinhardt; Co-founder, Bang on a Can

- David Lang (composer), Co-founder, Bang on a Can

- Joseph Waters, Professor of Music, San Diego State University

- Scott Lindroth, Professor and Vice Provost of the Arts, Duke University

Discography

- MUSIC FROM THE ONCE FESTIVAL 1961–1966 (1966) – New World 80567-2 (5 CDs)

- Epigram and Evolution (1960, piano)

- Wedge (1961, chamber ensemble)

- Mosaic (1962, flute and piano)

- A Portrait of Vanzetti (1962–63, narrator, ensemble, and tape)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: VOICESPACE (1980) – Lovely Music LCD 1801

- The Palace (Voicespace IV) (1980, baritone and tape)

- Eclipse (Voicespace III) (1979, tape)

- Still (Voicespace I) (1975, tape)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: ALL KNOWN ALL WHITE (1984) – Pogus P21025-2

- …the serpent-snapping eye (1978, trumpet, percussion, piano, and tape)

- Ping (1968, piano, flute, percussion, and live electronics)

- Traces (1969, flute, piano, cello, and live electronics)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: DISTANT IMAGES (1987) – Lovely Music VR 1803 7-4529-51803-1-9

- Less Than Two (1976–79, two pianos, two percussionists, and tape)

- Aether (1983, violin and piano)

- NEW MUSIC SERIES: VOLUME 2 (1988) – Neuma 45072

- Autumn Island (1986, for marimba)

- ARDITTI (1989) – Gramavision R2 79440

- Coconino … a shattered landscape (1985, revised 1993, string quartet)

- COMPUTER MUSIC CURRENTS 4 (1989) – Wergo WER 2024-50

- The Vanity of Words (1986, for computer processed vocal sounds)

- ROGER REYNOLDS (1989) – New World 80401-2

- Whispers Out of Time (1988, string orchestra)

- Transfigured Wind II (1983, flute, orchestra, and tape)

- ELECTRO ACOUSTIC MUSIC: CLASSICS (1990) – Neuma 450-74

- Transfigured Wind IV (1985, flute and tape)

- ROGER REYNOLDS (1990) – Neuma 450-78

- Personae (1990, violin, ensemble, and tape)

- The Vanity of Words [Voicespace V] (1986, tape)

- Variation (1988, piano)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: SOUND ENCOUNTERS (1990) – GM Recordings GM2039CD

- Roger Reynolds: The Dream of Infinite Rooms (1986, cello, orchestra, and tape)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: ELECTROACOUSTIC MUSIC (1991) – New World 80431-2

- The Ivanov Suite (1991, tape)Versions/Stages (1988–91, tape)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: SONOR ENSEMBLE (1993) – Composers Recordings, Inc. / Anthology of Recorded Music, Inc. NWCR652

- Not Only Night (1988, soprano, flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: THE PARIS PIECES (1995) – Neuma 450-91 (2 CD)

- Odyssey (1989–92, two singers, ensemble, and computer sound)

- Summer Island (1984, oboe and computer sound)

- Archipelago (1982–83, ensemble and computer sound)

- Autumn Island (1986, marimba)

- Fantasy for Pianist (1964, piano)

- ROGER REYNOLDS (1996) – Montaigne 782083 (2 CD)

- Coconino... a shattered landscape (1985, revised 1993, string quartet)

- Visions (1991, string quartet)

- Kokoro (1992, solo violin)

- Ariadne's Thread (1994, string quartet)

- Focus a beam, emptied of thinking, outward... (1989, solo cello)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: FROM BEHIND THE UNREASONING MASK (1998) – New World 80237-2

- From Behind the Unreasoning Mask (1975, trombone, percussion, and tape)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: WATERSHED (1998) – mode 70

- Watershed IV (1995, percussion and real-time sound spatialization)

- Eclipse (1979, computer generated and processed sound)

- The Red Act Arias [excerpt] (1997, for 8-channel computer sound)

- STEVEN SCHICK: DRUMMING IN THE DARK (1998) – Neuma 450-100

- Watershed I (1995, solo percussion)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: THREE CIRCUITOUS PATHS (2002) - Neuma 450-102

- Transfigured Wind III (1984, flute, ensemble, and tape)

- Ambages (1965, flute)

- Mistral (1985, chamber ensemble)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: LAST THING, I THINK, TO THINK ABOUT (2002) – EMF CD 044

- last things, I think, to think about (1994, baritone, piano, and tape)

- FLUE (2003) – Einstein Records EIN 021

- ...brain ablaze ... she howled aloud (2000–2003, one, two or three piccolos, computer processed sound, and real time spatialization)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: PROCESS AND PASSION (2004) – Pogus P21032-2 (2 CD)

- Kokoro (1992, violin)

- Focus a beam, emptied of thinking, outward... (1989, cello)

- Process and Passion (2002, violin, cello, and electronics)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: WHISPERS OUT OF TIME [works for orchestra] (2007) – mode 183

- Symphony [Myths] (1990, orchestra)

- Whispers Out of Time (1988, orchestra)

- Symphony [Vertigo] (1987, orchestra)

- ANTARES PLAYS WORKS BY PETER LIEBERSON AND ROGER REYNOLDS (2009) – New Focus Recordings FCR112

- Shadowed Narrative (1978–81, clarinet, violin, cello, piano)

- EPIGRAM AND EVOLUTION: COMPLETE PIANO WORKS OF ROGER REYNOLDS (2009) – mode 212/213

- Fantasy for Pianist (1964, piano)

- imAge/piano (2007, piano)

- Epigram and Evolution (1960, piano)

- Variation (1988, piano)

- imagE/piano (2007, piano)

- Traces (1968, flute, piano, live electronics)

- Less Than Two (1978, for 2 pianos, 2 percussionists and tape)

- The Angel of Death (1998–2001, piano, chamber orchestra and computer processed sound)

- MARK DRESSER: GUTS (2010) – Kadima Collective Recordings Triptych Series

- imAge/contrabass and imagE/contrabass (2008–2010)

- ROGER REYNOLDS: SANCTUARY (2011) – mode 232/33

- Sanctuary (2004 – 2007, percussion quartet & live electronics)

References

- ^ Hicken, Stephen (1997). "The Newest Music". American Record Guide.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kerner, Leighton (March 8, 1985). ""The Sudden Wind"". The Village Voice.

- ^ Hitchcock, H. Wiley (July). ""Current Chronicle"". The Musical Quarterly.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b "About". CRCA Website. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Soderberg, Steve. "Biography from the Roger Reynolds Collection". Library of Congress Performing Arts Encyclopedia. Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ Kiderra, Inga. "UC San Diego Faculty Member Receives 'Highest Honor' Appointment". News Center. University of California, San Diego. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Roger Reynolds". Composer Biography. C.F. Peters. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "National Symphony Orchestra: Christoph Eschenbach, conductor / Saint-Saëns's "Organ Symphony," plus the world premiere of Roger Reynolds's george WASHINGTON". Calendar. The Kennedy Center. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ May, Thomas. "george Washington". Program Notes. The Kennedy Center. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ Gann, Kyle (1997). American Music in the Twentieth Century. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. pp. 170–172.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Oteri, Frank J. (1 December 2009). "The Benefits of Being Outside the Loops: Roger Reynolds in conversation with Frank J. Oteri May 13, 2009". New Music Box.

- ^ http://adminrecords.ucsd.edu/Notices/2009/2009-8-4-2.html

- ^ a b c d e Reynolds, Karen. "History". rogerreynolds.com. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Reynolds, Roger (Spring 2007). "Ideals and Realities: A Composer in America". American Music. 25 (1). University of Illinois Press: 4–49. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Chute, Jim. "Engineer-turned-composer Roger Reynolds is organized yet highly adventurous". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Sign On San Diego. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Sollberger, Harvey. "Reynolds, Roger". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ Ruch, A. "Roger Reynolds". Apmonia: A Site for Samuel Beckett. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Sutro, Dirk. "UCSD Composer Roger Reynolds's 1968 PING Restored for 2011". This Week @ UCSD. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ "Music at Mills". Mills College Website. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reynolds, Roger (2007). "Image, Engagement, Technological Resource: An Interview with Roger Reynolds". Computer Music Journal. 31 (1): 10–28. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Levitin, Daniel J. (2004). "Editorial: Introduction to the Angel of Death Project". Music Perception. 22 (2): 167–170.

- ^ Brant, Brian. "Xenakis, UPIC, Continuum Electroacoustic & Instrumental works from CCMIX Paris". Mode Records Catalog. Mode Records. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ Pulitzer Foundation. "Pulitzer Prizes: Music". Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Reynolds, Roger. "Composer's Note: A Perspective on ILLUSION". Music and Musicians Database. Los Angeles Philharmonic. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ DeLio, Thomas (2005). Introduction to Mind Models. New York: Routledge. pp. ix.

External links

- Roger Reynolds

- Mode Artist Profile: Roger Reynolds

- Edition Peters: Roger Reynolds

- CDeMUSIC: Roger Reynolds

- Lovely Music Artist: Roger Reynolds

- The Modern Word: Roger Reynolds

- Library of Congress: Music, Theater & Dance: The Roger Reynolds Collection

- "Phembree/sandbox (biography, works, resources)" (in French and English). IRCAM.

- Roger Reynolds Interview by Bruce Duffie, December 12, 1989

Listening

- Art of the States: Roger Reynolds two works by the composer

Template:PulitzerPrize MusicComposers 1976–2000

Category:1934 births Category:Living people Category:20th-century classical composers Category:American composers Category:21st-century classical composers Category:Pulitzer Prize for Music winners Category:University of Michigan alumni Category:University of California, San Diego faculty Category:Musicians from Detroit, Michigan Category:Guggenheim Fellows