Syrian civil war

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (November 2013) |

| Syrian civil war | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Spring and Arab Winter, spillover of the Iraqi Civil War, War against the Islamic State, War on Terror, Kurdish–Turkish conflict, Arab–Israeli conflict, and the Iran–Israel/Iran–Saudi/Iran–Turkey proxy wars | |||||||

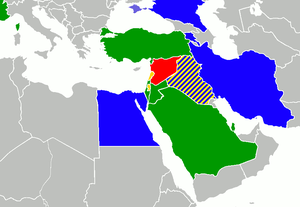

Military situation as of December 18, 2024 at 2:00pm ET Syrian transitional government: Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria: Syrian Interim Government: Other former rebel forces: Others: Uncertain/mixed

Islamic State presence

(full list of factions, detailed map) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total deaths 580,000[11]–617,910+[12] Civilian deaths 219,223–306,887+[e][13][14] Displaced people

| |||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ba'athism |

|---|

|

The Syrian Civil War, also known as the Syrian Uprising[16] or the Syrian Crisis (Template:Lang-ar),[17] is an ongoing armed conflict in Syria between forces loyal to the Ba'ath government and those seeking to oust it. The unrest began on 15 March 2011, with popular protests that grew nationwide by April 2011. These protests were part of the wider North African and Middle Eastern protest movements known as the Arab Spring. Syrian protesters at first demanded democratic and economic reform within the framework of the existing government. Months later, when the police and the army started suppressing the protests with force, protesters demanded the resignation of President Bashar al-Assad, whose family has held the presidency in Syria since 1971, as well as the end of Ba'ath Party rule, which began in 1963.

Starting in March 2011, tens of thousands of Syrian students, liberal activists and human rights advocates began being arrested.[18] In April 2011, the Syrian Army was deployed to quell the uprising and soldiers fired on demonstrators across the country.[19] After months of military sieges,[20] the protests evolved into an armed rebellion. The conflict is asymmetrical, with clashes taking place in many towns and cities across the country.[21] In 2013, Hezbollah entered the war in support of the Syrian army.[22][23] The Syrian government is further upheld by military support from Russia and Iran, while Qatar and Saudi Arabia transfer weapons to the rebels.[24] By July 2013, the Syrian government controls approximately 30–40 percent of the country's territory and 60 percent of the Syrian population.[25] A late 2012 UN report described the conflict as "overtly sectarian in nature"[26] between Alawite shabiha militias and other Shia groups fighting largely against Sunni-dominated rebel groups,[27] though both opposition and government forces denied that.[28][29]

According to the United Nations, the death toll surpassed 100,000 in June 2013, and reached 120,000 by September 2013.[30][31] In addition, tens of thousands of protesters have been imprisoned and there are reports of widespread torture and terror in state prisons.[32] International organizations have accused both government and opposition forces of severe human rights violations.[33] The UN and Amnesty International's inspections and probes in Syria determined both in 2012 and 2013 that the vast majority of abuses are done by the Syrian government, whose are also largest in scale.[34][35][36][37][38] The severity of the humanitarian disaster in Syria has been outlined by UN and many international organizations. More than four million Syrians have been displaced, more than three million Syrians fled the country and became refugees, and millions more were left in poor living conditions with shortage of food and drinking water. The situation is especially bad in the town of Muadamiyat al-Sham, where 12,000 residents are predicted to die of starvation by the winter of 2013 from a Syrian army enforced blockade.[39]

Chemical weapons have also been used in Syria on more than one occasion, triggering strong international reactions.[40]

Background

Advanced weaponry and tactics

Chemical weapons

The UN received complaints about possible chemical attacks on 16 occasions. Seven of them have been investigated (nine were dropped for lack of "sufficient or credible information") and in four cases the UN inspectors confirmed use of sarin gas. The reports, however, did not blame any party of using chemical weapons.[41]

The Syrian government has been accused of conducting several chemical attacks, the most serious of them being the 2013 Ghouta attacks.

The rebels have also been accused of conducting several chemical attacks, the most serious of which was the Khan al-Assal chemical attack. The Khan al-Assal attack took place on 19 March 2013, and was initially reported on Syrian state news agency, SANA. That missiles containing "chemical materials" may have been fired into the Khan al-Assal district in Aleppo and the Al Atebeh suburbs of Damascus, resulting in 25 dead. Both sides immediately accused each other of carrying out the attack, but neither side presented clear documentation.[42][43] Russian experts later visited the site, found samples of sarin, and assigned responsibility for the attack to the rebels.[44] UN weapons inspectors are also scheduled to visit the site in 2013.

On 29 April, another chemical attack was reported, this time in Saraqib, in which 2 died and 13 were injured. On 5 May, Turkish doctors said initial test show no traces of sarin had been found in the blood samples of victims.[45] French intelligence acquired blood, urine, earth and munitions samples from victims or sites of attacks on Saraqeb, on 29 April 2013, and Jobar, in mid April 2013. The analysis carried out confirms the use of sarin.[46]

On 13 June, the United States announced that there is definitive proof that the Assad government has used limited amounts of chemical weapons on multiple occasions on rebel forces, killing 100 to 150 people.[47] Internal US intelligence assessments by the CIA and DIA concluded that rebel forces also possessed chemical weapons capability, and that US forces would risk rebel sarin attack if deployed to Syria.[48]

On 5 August, another chemical attack by the Syrian army was reported by the opposition, who documented the injured with video footage. The activists claim up to 400 people were effected by the attack in Adra and Houma of the Damascus suburbs. The content of the chemicals used has not been identified yet.[49]

On 21 August, Jobar, Zamalka, 'Ain Tirma, and Hazzah in the Eastern Ghouta region were struck with chemical weapons. At least 635 people were killed in the nerve gas attacks. The Ghouta chemical attacks were confirmed after a three-week investigation conducted by the UN, who also confirmed the main agent used in the chemical attacks was sarin gas.[50] The Mission "collected clear and convincing evidence that surface-to-surface rockets containing the nerve agent sarin were used in the Ein Tarma, Moadamiyah and Zalmalka in the Ghouta area of Damascus." Third party analyses of the evidence reported by the UN showed that the sarin gas was military grade, and the rockets that delivered the sarin may have been launched from Syrian army or rebel controlled territory.[48][51][52] On 19 December, Russian Ambassador to the UN said that rebels in Syria were behind a chemical weapons attack in August. "It is absolutely obvious that on August 21 a wide scale provocation was staged to provoke foreign military intervention," said Russian Ambassador to the UN Vitaly Churkin on Monday following a UN Security Council meeting.[53]

On 9 September, Russia urged Syria to put its' chemical weapons stockpile under international control. The initiative was expressed in the wake of American threat of attacking Syria after the chemical attack of 21 August.[54][55] On 14 September, US and Russia announced in Geneva that they reached a deal on how Assad should give up his chemical weapons.[56]

Cluster bombs

The Syrian army began using cluster bombs in September 2012. Steve Goose, director of the Arms division at Human Rights Watch said "Syria is expanding its relentless use of cluster munitions, a banned weapon, and civilians are paying the price with their lives and limbs,” "The initial toll is only the beginning because cluster munitions often leave unexploded bomblets that kill and maim long afterward."[57]

Scud missile attacks

In December 2012, the Syrian government began using Scud missiles on rebel-held towns, primarily targeting Aleppo.[58] On 19 February, four Scud missiles were fired, three landed in Aleppo city and one on Tell Rifaat town, Aleppo governorate. Between December and February, at least 40 Scud missile landings were reported.[59] Altogether, Scud missiles killed 141 people in the month of February.[60] The United States condemned the Scud missile attacks.[61] On 1 March, a Scud missile landed in Iraq. It is believed that the intention was to hit the Deir Ezzor governate.[62] On 29 March, a Scud missile landed on Hretan, Aleppo, killing 20 and injuring 50.[63] On 28 April, a Scud missile landed on Tell Rifaat, killing four, two of them women and two of them children, SOHR reported.[64] On 3 June, a surface to surface missile, not confirmed as a Scud, hit the village of Kafr Hamrah around midnight killing 26 people including six women and eight children according to SOHR.[65]

Suicide bombings

Rebel suicide bombings began in December 2011; the Al-Nusra Front has claimed responsibility for 57 out of 70 similar attacks through April 2013.[22][66] The bombings have claimed numerous civilian casualties.[67]

A Syrian Army officer has claimed the Syrian Army would prepare 8,000 soldiers for suicide bombings in the event of NATO military intervention, including 13 kamikaze pilots.[68]

Barrel bombs

A barrel bomb is a type of improvised explosive device used by the Syrian Air Force. Typically, a barrel is filled with a large amount of TNT, and possibly shrapnel and oil, and dropped from a helicopter. The resulting detonation can be devastating.[69][70][71]

Thermobaric weapons

Thermobaric weapons, also known as "fuel-air bombs," have been used by the government side during the Syrian civil war. Since 2012, rebels have claimed that the Syrian Air Force (government forces) is using thermobaric weapons against residential areas occupied by the rebel fighters, such as during the Battle of Aleppo and also in Kafr Batna.[72][73] A panel of United Nations human rights investigators reported that the Syrian government used thermobaric bombs against the strategic town of Qusayr in March 2013.[74] In August 2013, the BBC reported on the use of napalm-like incendiary bombs on a school in northern Syria.[75]

Syrian government affiliated parties

Syrian Army

Before this uprising and war broke out, the force of the Syrian Army was estimated at 325,000 regular troops of which 220,000 ‘army troops’ and the rest in navy, air force and air defences; and additionally 280,000-300,000 reservists.

Since June 2011, defections of soldiers are being reported. By July 2012, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights estimated tens of thousands soldiers to have defected, a Turkish official estimated 60,000 soldiers to have defected. According to Western experts, this did not yet harm the strength of that army; the defecting soldiers were mainly Sunnis without access to vital command and control in the army. In August 2013, the strength of the Syrian army had dropped to 178,000 regular troops, likely due to defections, desertions and casualties, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London.

National Defense Force

The Syrian NDF was to formed out of pro-government militias. They receive their salaries, their military equipment from the government,[76][77] and currently numbers at around 100,000.[78][79] The force acts in an infantry role, directly fighting against rebels on the ground and running counter-insurgency operations in coordination with the army, which provides them logistical and artillery support. The force has a 500-strong women's wing called "Lionesses of National Defense" which operates checkpoints.[80]

NDF soldiers are allowed to take loot from battlefields, which can then be sold for extra money.[76]

Shabiha

The Shabiha are unofficial pro-government militias drawn largely from Assad's Alawite minority group. Since the uprising, the Syrian government has frequently used shabiha to break up protests and enforce laws in restive neighborhoods.[81] As the protests escalated into an armed conflict, the opposition started using the term shabiha to describe any civilian Assad supporter taking part in the government's crackdown on the uprising.[82] The opposition blames the shabiha for the many violent excesses committed against anti-government protesters and opposition sympathizers,[82] as well as looting and destruction.[83][84] In December 2012, the shabiha were designated a terrorist organization by the United States.[85]

Bassel al-Assad is reported to have created the shabiha in the 1980s for government use in times of crisis.[86] Shabiha have been described as "a notorious Alawite paramilitary, who are accused of acting as unofficial enforcers for Assad's regime";[87] "gunmen loyal to Assad",[88] and, according to the Qatar-based Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, "semi-criminal gangs comprised of thugs close to the regime".[88] Despite the group's image as an Alawite militia, some shabiha operating in Aleppo have been reported to be Sunnis.[89]

In 2012, the Assad government created a more organized official militia known as the Jaysh al-Sha'bi, allegedly with help from Iran and Hezbollah. As with the shabiha, the vast majority of Jaysh al-Sha'bi members are Alawite and Shi'ite volunteers.[90][91]

Hezbollah

General Secretary Nasrallah denied Hezbollah had been fighting on behalf of the Syrian government, stating in a 12 October 2012 speech that "right from the start the Syrian opposition has been telling the media that Hezbollah sent 3,000 fighters to Syria, which we have denied".[92]

However, according to the Lebanese Daily Star newspaper, Nasrallah said in the same speech that Hezbollah fighters helped the Syrian government "retain control of some 23 strategically located villages [in Syria] inhabited by Shiites of Lebanese citizenship". Nasrallah said that Hezbollah fighters have died in Syria doing their "jihadist duties".[93]

In 2012, Hezbollah fighters crossed the border from Lebanon and took over eight villages in the Al-Qusayr District of Syria.[94]

Former secretary general of Hezbollah, Sheikh Subhi al-Tufayli, confirmed in February 2013 that Hezbollah was fighting for the Syrian army.[95]

On 12 May, Hezbollah, with the Syrian army, attempted to retake part of Qusayr.[96] By the end of the day, 60 percent of the city, including the municipal office building, were under pro-Assad forces.[96] In Lebanon, there have been "a recent increase in the funerals of Hezbollah fighters" and "Syrian rebels have shelled Hezbollah-controlled areas."[96]

As of 14 May, Hezbollah fighters were reported to be fighting alongside the Syrian army, particularly in the Homs Governorate.[97] And Hassan Nasrallah has called on Shiites and Hezbollah to protect the shrine of Sayida Zeinab.[97] President Bashar al-Assad denied in May 2013 that there were foreign fighters, Arab or otherwise, fighting for the government in Syria.[98]

On 25 May, Nasrallah announced that Hezbollah was fighting in the Syria against Islamic extremists and "pledged that his group will not allow Syrian militants to control areas that border Lebanon".[99] He confirmed that Hezbollah was fighting in the strategic Syrian town of Qusayr on the same side as Assad's forces.[99] In the televised address, he said, "If Syria falls in the hands of America, Israel and the takfiris, the people of our region will go into a dark period."[99]

According to independent analysts, by the beginning of 2014, approximately 500 Hezbollah fighters had died in the Syrian conflict.[100]

Iran

Since the start of the civil war, Iran has expressed its support for the Syrian government and provided it with support in several ways: financial, technical, and military.[101]

Opposition parties

Syrian National Council

Formed on 23 August 2011, the National Council is a coalition of anti-government groups, based in Turkey. The National Council seeks the end of Bashar al-Assad's rule and the establishment of a modern, civil, democratic state. SNC has links with the Free Syrian Army.

In November 2012, the council agreed to unify with several other opposition groups to form the Syrian National Coalition. The SNC has 22 out of 60 seats of the Syrian National Coalition.[102]

Syrian National Coalition

On 11 November 2012 in Doha, the National Council and other opposition forces united as the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces.[103] The following day, it was recognized as the legitimate government of Syria by numerous Persian Gulf states. Delegates to the Coalition's leadership council are to include women and representatives of religious and ethnic minorities, including Alawites. The military council will reportedly include the Free Syrian Army.[104]

The main aims of the National Coalition are replacing the Bashar al-Assad government and "its symbols and pillars of support", "dismantling the security services", unifying and supporting the Free Syrian Army, refusing dialogue and negotiation with the al-Assad government, and "holding accountable those responsible for killing Syrians, destroying [Syria], and displacing [Syrians]".[105]

Free Syrian Army

The Free Syrian Army (FSA) is the main armed opposition in Syria. Its formation was announced in late July 2011 by a group of defecting Syrian Army officers. In a video, the men called upon Syrian soldiers and officers to defect to their ranks, and said the purpose of the Free Syrian Army was to defend civilian protesters from violence by the state.[106] Many Syrian soldiers subsequently deserted to join the FSA.[107] The actual number of soldiers who defected to the FSA is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 1,000 to over 25,000 by December 2011.[108] The FSA functions more as an umbrella organization than a traditional military chain of command, and is "headquartered" in Turkey. As such, it cannot issue direct orders to its various bands of fighters, but many of the most effective armed groups are fighting under the FSA's banner.

As deserting soldiers abandoned their armored vehicles and brought only light weaponry and munitions, FSA adopted guerilla-style tactics against government security forces in urban areas. Initially, its primary target has been the Shabiha militias; most FSA attacks are directed against trucks and buses that are believed to carry security reinforcements. Sometimes, the occupants of government vehicles are taken as hostages, while in other cases the vehicles are attacked either with roadside bombs or with hit-and-run attacks. To encourage defection, the FSA began attacking army patrols, shooting the commanders and trying to convince the soldiers to switch sides. FSA units have also acted as defense forces by guarding neighborhoods with strong opposition presences, patrolling streets while protests take place, and attacking Shabiha members. As the insurgency grew, the FSA began engaging in urban battles against the Syrian Army.

In May 2013, Salim Idriss, one of the FSA leaders, acknowledged that rebels were badly fragmented and lacked the military skill needed to topple the government of President Bashar al-Assad. He said it was difficult to unify rebels because many of them were civilians and only a few of them had military service. Idriss said he was working on a countrywide command structure, but that a lack of material support was hurting that effort. He pointed out shortage of ammunition and weapons, fuel for the cars and money for logistics and salaries. "The battles are not so simple now,” Idriss said. "At the beginning of the revolution, they had to fight against a checkpoint. They had to fight against a small group of the army. Now they have to liberate an air base. Now they have to liberate a military school. Small units can't do that alone, and now it is very important for them to be unified. But unifying them in a manner to work like a regular army is still difficult." He denied any cooperation with Al-Nusra Front but acknowledged common operations with another Islamist group Ahrar ash-Sham. In April the US announced it would transfer $123 million of aid through his group.[109] In late September, it was reported that the Army and rebels in some areas have ceased hostilities, and individual FSA-linked parties have begun attempts to start dialogue.[110]

Mujahideen

In September 2013, US Secretary of State John Kerry stated that extremist groups make up 15–25% of rebel forces.[111] According to Charles Lister, about 12% of rebels are part of groups linked to Al-Qaeda, 18% belong to Ahrar ash-Sham, and 9% belong to Suqour al-Sham Brigade.[112][113] Foreign fighters have joined the conflict in opposition to Assad. While most of them are jihadists, some individuals, such as Mahdi al-Harati, have joined to support the Syrian opposition.[114]

The ICSR estimates that 2,000–5,500 foreign fighters have gone to Syria since the beginning of the protests, about 7–11 percent of whom came from Europe. It is also estimated that the number of foreign fighters does not exceed 10 percent of the opposition armed forces.[115] Another estimate puts the number of foreign jihadis at 15,000 by early 2014[116] ), The European Commission expressed concerns that some of the fighters might use their skills obtained in Syria to commit acts of terrorism back in Europe in the future.[117]

The most significant group is Al-Nusra Front, headed by Abu Mohammed al-Golani, which probably accounts for up to a quarter of opposition fighters in Syria. It includes some of the rebellion's most battle-hardened and effective fighters, coming from Bosnia, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Tunisia, Palestine, Lebanon, Australia, Chechnya, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Azerbaijan, France, Iraq, Spain, Denmark, and Tajikistan.[118]

After the civil war in Libya had finished, fighters from there began moving to Syria through Turkey. It was reported by Syrian opposition that foreigners brought heavy weapons with them, including surface-to-air missiles. However, Libyans denied that claim.[119] Abdulhakim Belhadj, head of the Tripoli Military Council, met with FSA leaders near the border with Turkey. The meetings were a sign of growing ties between new Libyan government and Syrian opposition. The arrangements included transfers of money and weapons, as well as training of the rebels by skilled fighters from Libya.[120] One of the Libya's most known rebel commanders, Mahdi al-Harati, traveled to Syria in a group of 30 fighters, to form Liwaa al-Umma there.[121]

In October 2012, various Iraqi religious groups join the conflict in Syria on both sides. Radical Sunnis from Iraq, have traveled to Syria to fight against President Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian government.[122] Also, Shiites from Iraq, in Babil Province and Diyala Province, have traveled to Damascus from Tehran, or from the Shiite Islamic holy city of Najaf, Iraq to protect Sayyida Zeinab, an important mosque and shrine of Shia Islam in Damascus.[122]

Hundreds of young Saudis were reported to travel through Turkey or Jordan in order to fight against Assad in Syria. In one documented case, a judge encouraged a group of convicted young men to "fight against the real enemy, the Shia". Most of them joined Syrian rebels. Since convicted criminals cannot leave Saudi Arabia without Interior Ministry permission, it is suspected that officials silently allow them to travel to fight.[123]

Government of Tunisia estimated that about 800 of its citizens were fighting alongside Islamist forces in Syria. However, unofficial sources at Interior Ministry put the number as high as 2,000.[124]

Hundreds of Egyptian fighters are suspected to be involved in Syrian conflict. Some of them traveled there and back several times. The government officially confirmed 10 "martyrs".[125]

8 Spanish citizens have been arrested in Ceuta. These individuals have been accused of training and organising the movement of Spaniards to fight in Syria, with the group having links to Al-Qaeda. Some 500 European citizens, according to EU counter-terrorism head Gilles de Kerchove, are fighting in Syria, two British citizens and an American woman have been killed in Syria so far.[126]

In September 2013, leaders of 13 powerful rebel brigades rejected Syrian National Coalition and called Sharia law "the sole source of legislation". In a statement they declared that "the coalition and the putative government headed by Ahmad Tomeh does not represent or recognize us". Among the signatory rebel groups were Al-Nusra Front, Ahrar ash-Sham and Al-Tawheed.[127] In November 2013, seven Islamist groups combined to form the Islamic Front.

Al-Nusra Front

The al-Nusra Front, being the biggest jihadist group in Syria, is often considered to be the most aggressive and violent part of the opposition.[128] Being responsible for over 50 suicide bombings, including several deadly explosions in Damascus in 2011 and 2012, it is recognized as a terrorist organization by Syrian government and was designated as such by United States in December 2012.[22]

In April 2013, the leader of the Islamic state of Iraq released an audio statement announcing that al-Nusra Front is its branch in Syria.[129] The leader of Al Nusra, Abu Mohammad al-Golani, said that the group will not merge with the Islamic state of Iraq, but still maintain allegiance to Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of al-Qaeda.[130]

The relationship between the Al-Nusra Front and the indigenous Syrian opposition is tense, even though al-Nusra Front has fought alongside the FSA in several battles. The Mujahideen's strict religious views and willingness to impose sharia law disturbed many Syrians.[131] Some rebel commanders have accused foreign jihadists of "stealing the revolution", robbing Syrian factories and displaying religious intolerance.[132]

Al-Nusra Front has been accused of mistreating religious and ethnic minorities since their formation.[133] The estimated manpower of al-Nusra Front is approximately 6,000–10,000 people, including many foreign fighters.[118]

ISIS

The ISIS, (also called Da'āsh or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) made rapid military gains in Northern Syria starting in April 2013 and as of late 2013 controls large parts of that region, where the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights describes it as "the strongest group".[134] It has imposed strict Sharia law over land that it controls. The group is affiliated with Al Qaeda, led by the Iraqi fighter Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and has an estimated 7,000 fighters in Syria, including many non-Syrians. It has been praised as less corrupt than other militia groups, and criticized for abusing human rights[135] and for not tolerating non-Islamist militia groups, foreign journalists or aid workers, whose members it has expelled or imprisoned.[136]

Sectarianism and minorities

Both the opposition and government have accused each other of employing sectarian agitation. The successive governments of Hafez and Bashar al-Assad have been closely associated with the country's minority Alawite religious group, an offshoot of Shia, whereas the majority of the population, and thus most of the opposition, is Sunni, lending plausibility to such charges, even though both leaderships claim to be secular.

Kurds

Kurds – mostly Sunni Muslims, with a small minority of Yezidis – represented 10% of Syria's population at the start of the uprising in 2011. They had suffered from decades of discrimination and neglect, being deprived of basic civil, cultural, economic, and social rights.[137]: 7 When protests began, Assad's government finally granted citizenship to an estimated 200,000 stateless Kurds, in an effort to try and neutralize potential Kurdish opposition.[138] This concession, combined with Turkish endorsement of the opposition and Kurdish under-representation in the Syrian National Council, has resulted in Kurds participating in the civil war in smaller numbers than their Syrian Arab Sunni counterparts.[138] Consequently, violence and state repression in Kurdish areas has been less severe.[138] In terms of a post-Assad Syria, Kurds reportedly desire a degree of autonomy within a decentralized state.[139]

Since the outset of the civil war, numerous Kurdish political parties have organised themselves into an umbrella organisation, the Kurdish National Council. Until October 2011, most of these parties were members of the NCC. After October 2011, only the PYD remained in the NCC, holding a more moderate stance regarding the Assad government.

The conflict between the Kurdish People's Protection Units (YPG) and Islamists groups such as al-Nusra Front have escalated since a group of Kurds expelled Islamists from the border town of Ras al-Ain.[140]

Palestinians

The reaction of the approximately 500,000 Palestinians living in Syria to the conflict has been mixed.[141] Syria's Palestinian community largely remained neutral in the early days of the uprising.[142] Ongoing government attacks and shelling have caused any pro-government sympathies among the Palestinians in Syria to dwindle severely.[141] According to the UN, 75% of the Palestinians in Syria have been affected by the uprising, and more than 600 of them have been killed.[143] Although many Palestinians are appreciative of the civil rights given to them by the Syrian government, in comparison to other Arab states, these same rights have allowed the younger generation of Palestinians to be "raised essentially as Syrians" who "find it hard not to be swept up in the fervor on the streets", according to the New York Times.[144]

While major Palestinian factions such as Hamas have turned against the Syrian government, other groups, particularly the PFLP-General Command (PFLP-GC), have remained supportive. The PFLP-GC has been accused by pro-rebel Palestinians of actively participating in the conflict as secret police in the refugee camps.[144] In late October 2012, pro-rebel Palestinians formed the Storm Brigade with the task of wresting control of the Yarmouk Camp in Damascus from pro-government groups.[145]

In January 2014, the Syrian army launched a siege and blockade on the Yarmouk Palestinian Refugee camp in an attempt to starve out the residents and rebels inside the camp.[146] Reuters reported that the Syrian government was insisting dangerous and circuitous routes be used to deliver aid and of 'hampering deliveries to opposition-controlled areas' and further threatening groups with expulsion if they tried to avoid bureaucratic obstacles. [147]

Christians

Christians are generally considered to have a favorable situation under the Syrian government, considered to be "protector" of minorities. Numerous abuses were recorded by the opposition forces against Christians as a result, most notably by Mujahedeen units. Unknown, but significant numbers of Christians, have fled the country since 2011, relocating to Lebanon and Europe. A number of Oriental Orthodox (Syriac) Christians have also returned to Turkey, which was their historic homeland before many of them had fled to Syria during World War I. The Syriac community in Tur Abedin has been swelling from an influx of both Syrian refugees and returned diaspora Syriacs from the West.[148] Notably, during the civil war, Islamist rebels invaded the historic Christian town of Maloula.[149]

There are Christian militias active in Syria; these include Sutoro and the Syriac Military Council.

International reaction

The Arab League, European Union, the United Nations,[150] and many Western governments quickly condemned the Syrian government's violent response to the protests, and expressed support for the protesters' right to exercise free speech.[151] Initially, many Middle Eastern governments expressed support for Assad, but as the death toll mounted they switched to a more balanced approach, criticizing violence from both government and protesters. Both the Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation suspended Syria's membership. Russia and China vetoed Western-drafted United Nations Security Council resolutions in 2011 and 2012, which would have threatened the Syrian government with targeted sanctions if it continued military actions against protestors.[152] Recently, the United Nations prepared an 22 January 2014 international peace conference in Geneva, in which both the Syrian government and opposition have promised to participate.

Humanitarian help

The international humanitarian response to the conflict in Syria is coordinated by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) in accordance with General Assembly Resolution 46/182.[153] The primary framework for this coordination is the Syria Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP) which appealed for USD $1.41 billion to meet the humanitarian needs of Syrians affected by the conflict.[154] Official United Nations data on the humanitarian situation and response is available at http://syria.unocha.org/; an official website managed by UNOCHA Syria (Amman).

Financial information on the response to the SHARP, as well as assistance to refugees and for cross-border operations, can be found on UNOCHA's Financial Tracking Service. As at 18 September 2013, the top ten donors to Syria were: United States, European Commission, Kuwait, United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, Japan, Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Denmark.[155] USAID and other government agencies in US delivered nearly $385 million of aid items to Syria in 2012 and 2013. The United States is providing food aid, medical supplies, emergency and basic health care, shelter materials, clean water, hygiene education and supplies, and other relief supplies.[156] Islamic Relief has stocked 30 hospitals and sent hundreds of thousands of medical and food parcels.[157]

Other countries in the region have also contributed various levels of aid. Iran has been exporting between 500 and 800 tonnes of flour daily to Syria.[158] Israel has granted special entry permits for over 100 wounded Syrians to be treated at Israeli medical facilities, and has set up a field hospital on the Syrian border.[159][160][161] On 26 April 2013, a humanitarian convoy, inspired by Gaza Flotilla, departed from Turkey to Syria. Called Hayat ("Life"), it is set to deliver aid items to IDPs inside Syria and refugees in neighboring countries: Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt.[162]

The World Health Organization has reported that 35% of the country's hospitals are out of service and, depending upon the region, up to 70% of health care professionals have fled. Cases of diarrhoea and hepatitis A have increased by more than twofold since the beginning of 2013. Due to fighting, the normal vaccination programs cannot be undertaken. The displaced refugees may also pose a risk to countries to which they have fled.[163]

Foreign involvement

The Syrian civil war has received significant international attention, and both the Syrian government and the opposition have received support, militarily and diplomatically, from foreign countries.

The main Syrian opposition body – the Syrian coalition - receives political, logistic and military support from the US, Britain and France.[164][165][166] The Syrian coalition also receives logistic and political support from major Sunni states in the Middle East, most notably Turkey, Qatar and Saudi Arabia; all the three major supporting states however have not contributed any troops for direct involvement in the war, though Turkey was involved in a number of border incidents with Syrian Army. The major Syrian Kurdish opposition group, the PYD, was reported to get logistic and training support from Iraqi Kurdistan. Islamist militants in Syria were reported to receive support from private funders, mainly in the Persian Gulf area, as well as from Al-Qaeda in Iraq.

The major parties supporting the Syrian Government are Iran and Hezbollah. Both of these are involved in the war politically and logistically by providing military equipment, training and battle troops. The Syrian government has also received arms and political support from Russia and reports have said North Korea, which has 'longstanding ties' to the Assad government, has sent artillery officers, advisors and helicopter pilots.[167]

Video footage

Between January 2012 and September 2013, over a million videos documenting the war have been uploaded, and they have received hundreds of millions of views.[168] The Wall Street Journal states that the "unprecedented confluence of two technologies—cellphone cams and social media—has produced, via the instant upload, a new phenomenon: the YouTube war." The New York Times states that online videos have "allowed a widening war to be documented like no other."[169]

Impact

Deaths

Estimates of deaths in the conflict vary widely, with figures, per opposition activist groups, ranging from 95,150 and 130,435.[170][171][172][173] On 2 January 2013, the United Nations stated that 60,000 had been killed since the civil war began, with UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay saying "The number of casualties is much higher than we expected, and is truly shocking."[174] Four months later, the UN's updated figure for the death toll had reached 80,000.[175] On 13 June, the UN released an updated figure of people killed since fighting began, the figure being exactly 92,901, for up to the end of April 2013. Navi Pillay, UN high commissioner for human rights, stated that: "This is most likely a minimum casualty figure." The real toll was guessed to be over 100,000.[30][176] Some areas of the country have been affected disproportionately by the war; by some estimates, as many as a third of all deaths have occurred in the city of Homs.[177]

One problem has been determining the number of "armed combatants" who have died, due to some sources counting rebel fighters who were not government defectors as civilians.[178] At least half of those confirmed killed have been estimated to be combatants from both sides, including 52,290 government fighters and 29,080 rebels, with an additional 50,000 unconfirmed combatant deaths.[170] In addition, UNICEF reported that over 500 children had been killed by early February 2012,[179] and another 400 children have been reportedly arrested and tortured in Syrian prisons;[180] both of these claims have been contested by the Syrian government. Additionally, over 600 detainees and political prisoners are known to have died under torture.[181] In mid-October 2012, the opposition activist group SOHR reported the number of children killed in the conflict had risen to 2,300,[182] and in March 2013, opposition sources stated that over 5,000 children had been killed.[171]

Refugees

The violence in Syria has caused millions to flee their homes. In August 2012, the United Nations said more than one million people were internally displaced,[183] and, in September 2013, the UN reported that more than 6.5 million Syrians had been displaced, of whom 2 million fleeing to neighboring countries, 1 in 3 of those refugees (about 667,000 people) seeking safety in tiny Lebanon (normally 4,8 million population).[184] Others have fled to Jordan, Turkey, and Iraq. Turkey has accepted 400,000 Syrian refugees, half of whom are spread around a dozen camps placed under the direct authority of the Turkish Government. Satellite images confirmed that the first Syrian camps appeared in Turkey in July 2011, shortly after the towns of Deraa, Homs, and Hama were besieged.[185] On 9 October 2012, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that the number of external Syrian refugees stood at between 355,000 to 500,000.[186] In September 2013, the UN stated that the number of Syrian refugees had exceeded 2 million.[187]

Human rights violations

According to various human rights organizations and United Nations, human rights violations have been committed by both the government and the rebels, with the vast majority of the abuses having been committed by the Syrian government.[188][189]

The U.N. commission investigating human rights abuses in Syria confirms at least 9 intentional mass killings in the period 2012 to mid-July 2013, identifying the perpetrator as Syrian government and its supporters in eight cases, and the opposition in one.[190][191]

By late November 2013, according to the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network (EMHRN) report entitled “Violence against Women, Bleeding Wound in the Syrian Conflict”, approximately 6,000 women have been raped (including gang-rape) since the start of the conflict - with figures likely to be much higher given that most cases go unreported.[192][193][194]

Economy

By July 2013, the Syrian economy has shrunk 45 percent since the start of the conflict. Unemployment increased fivefold, the value of the Syrian currency decreased to one-sixth its pre-war value, and the public sector lost USD $15 billion.[195][196]

Crime wave

As the conflict has expanded across Syria, many cities have been engulfed in a wave of crime as fighting caused the disintegration of much of the civilian state, and many police stations stopped functioning. Rates of thievery increased, with criminals looting houses and stores. Rates of kidnappings increased as well. Rebel fighters were sighted stealing cars and destroying an Aleppo restaurant in which Syrian soldiers had eaten.[197]

By July 2012, the human rights group Women Under Siege had documented over 100 cases of rape and sexual assault during the conflict, with many of these crimes believed to be perpetrated by the Shabiha and other pro-government militias. Victims included men, women, and children, with about 80% of the known victims being women and girls.[198]

Criminal networks have been used by both the government and the opposition during the conflict. Facing international sanctions, the Syrian government relied on criminal organizations to smuggle goods and money in and out of the country. The economic downturn caused by the conflict and sanctions also led to lower wages for Shabiha members. In response, some Shabiha members began stealing civilian properties, and engaging in kidnappings.[81]

Rebel forces sometimes relied on criminal networks to obtain weapons and supplies. Black market weapon prices in Syria's neighboring countries have significantly increased since the start of the conflict. To generate funds to purchase arms, some rebel groups have turned towards extortion, stealing, and kidnapping.[81]

Cultural heritage

The civil war has caused significant damage to Syria's cultural heritage, including World Heritage Sites. Destruction of antiquities has been caused by shelling, army entrenchment, and looting at various tells, museums, and monuments.[199] A group called Syrian archaeological heritage under threat is monitoring and recording the destruction in an attempt to create a list of heritage sites damaged during the war and gain global support for the protection and preservation of Syrian archaeology and architecture.[200] An air raid on Syria's famed Krak des Chevaliers castle, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has damaged one of the fortress's towers. The footage shows a huge blast as a tower of the Crusader castle appears to take a direct hit, throwing up large clouds of smoke, and scattering debris in the air. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights could not confirm direct hits on the castle, but said there were reports of three air strikes in the area on 11 July 2013.[citation needed]

Art

The war has produced its own particular artwork. A late Summer 2013 exhibition in London at the P21 Gallery was able to show some of this work.[201]

Lebanon

The Syrian government has bombed targets in Lebanon several times. Most recently, on 1 Jan 2014, 10 Syrians were wounded when government forces bombed the Jroud Arsal hills near the Lebanese town of Arsal.[202]

See also

References

- ^ "Golan Heights: Trump signs order recognising occupied area as Israeli". BBC News. 25 March 2019.

- ^ "The Golan Heights: What's at Stake With Trump's Recognition". www.cfr.org. Council on Foreign Relations. 28 March 2019.

- ^ "Syrian Civil War Enters 10th Year". Voice of America. RFE/RL. 15 March 2020. Archived from the original on 3 April 2024.

- ^ "Syria: Grim 10-year anniversary of 'unimaginable violence and indignities'". UN News. 15 March 2021. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024.

- ^ Sherlock, Ruth; Neuman, Scott; Homsi, Nada (15 March 2021). "Syria's Civil War Started A Decade Ago. Here's Where It Stands". NPR. Archived from the original on 18 April 2024.

- ^ Ozcan, Ethem Emre (14 March 2021). "10 years since start of Syrian civil war". Anadolu Ajansı. Archived from the original on 26 November 2023.

- ^ Romey, Kristin (9 March 2022). "11 years into Syria's civil war, this is what everyday life looks like". National Geographic. Photographs by Keo, William. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Twelve years on from the beginning of Syria's war". Al Jazeera. 15 March 2023. Archived from the original on 3 July 2024.

- ^ Nawaz, Amna; Warsi, Zeba; Cebrián Aranda, Teresa (15 March 2023). "Syrians mark 12 years of civil war with no end in sight". PBS News. Archived from the original on 20 June 2024.

- ^ "Why has the Syrian war lasted 12 years?". BBC News. 15 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 July 2024.

- ^ "Syria". GCR2P. 1 December 2022. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Syrian Revolution 13 years on | Nearly 618,000 persons killed since the onset of the revolution in March 2011". Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "UN Human Rights Office estimates more than 306,000 civilians were killed over 10 years in Syria conflict". United Nations. 28 June 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- ^ "Civilian Deaths in the Syrian Arab Republic: Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights". United Nations. 28 June 2022. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022.

Over the past ten years, civilians have borne the brunt of the conflict, with an estimated 306,887 direct civilian deaths occurring.

- ^ "Syria emergency". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

- ^ "bomber targets Damascus shrine as 35 killed". 15 June 2012.

- ^ الأزمة السورية United Nations, 4 September 2012

- ^ Spiegel,October 10 2013

- ^ "We've Never Seen Such Horror". Human Rights Watch. 1 June 2011.

- ^ "Bombardment of Syria's Homs kills 21 people". Reuters. 22 February 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Syria what you need to know". Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ a b c "Al Nusrah Front claims 3 more suicide attacks in Daraa". 27 November 2012.

- ^ "Hezbollah's elite leading the battle in Qusayr region of Syria". Ya Libnan. 22 April 2013.

- ^ "In Turnabout, Syria Rebels Get Libyan Weapons". 21 June 2013.

- ^ Hubbard, Ben (17 July 2013). "Momentum Shifts in Syria, Bolstering Assad's Position". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ "UN says Syria conflict is 'overtly sectarian'". 20 December 2012.

- ^ Sunni v Shia, here and there. Retrieved 14 September 2013

- ^ "Nasrallah says Hezbollah will not bow to sectarian threats". NOW News. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Staff (22 December 2012). "Syria Opposition Contradicts U.N., Says Conflict not Sectarian". Naharnet. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ a b "More than 2,000 killed in Syria since Ramadan began". Timesofoman.com. 25 July 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ^ "France urges action on Syria, says 120,000 dead". Alliance News. 25 September 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Syria torture archipelago".

- ^ Staff (24 May 2012). "UN human rights probe panel reports continuing 'gross' violations in Syria". United Nations. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "UN must refer Syria war crimes to ICC: Amnesty". Agence France-Presse. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Laura Smith-Spark (16 March 2013). "Syrian general apparently defects, says morale among troops at a low". CNN. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Syrian troops committed war crimes, says UN report". The Independent. 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Syrian govt forces and rebels committing war crimes-U.N. report". Reuters. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 21 October 201.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Commission of Inquiry on Syria: civilians bearing the brunt of the "unrelenting spiral of violence"". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 18 September 2012. Retrieved 21 October 201.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Dagher, Sam (2 October 2013). "Syrian Regime Chokes Off Food to Town That Was Gassed". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Obama: US cannot ignore Syria chemical weapons". BBC. 7 September 2013.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Barnard, Anne (19 March 2013). "Syria and Activists Trade Charges on Chemical Weapons". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Chulov, Martin (19 March 2013). "Syria attacks involved chemical weapons, rebels and regime claim". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ BBC, 19 March 2013, Syrians trade Khan al-Assal chemical weapons claims

- ^ "Turkish doctors say no nerve gas in Syrian victims' blood". GlobalPost. 5 May 2013.

- ^ Willsher, Kim (2 September 2013). "Syria crisis: French intelligence dossier blames Assad for chemical attack". The Guardian.

- ^ "Syria Has Used Chemical Arms on Rebels, U.S. and Allies Find". The New York Times. 13 June 2013.

- ^ a b Hersh, Seymour (8 December 2013). "Whose Sarin?". London Review of Books. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Ari Soffer (5 August 2013). "Syria: Rebels Allege Another Chemical Attack by Regime". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "UN Chemical Weapons Report Will Confirm Sarin Gas Used in Aug. 21 Attack". 16 September 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gladstone, Rick; Chivers, C.J. (16 September 2013). "Forensic Details in U.N. Report Point to Assad's Use of Gas". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ^ Drum, Kevin (16 September 2013). "Yep, the Ghouta Gas Attacks Were Carried Out By the Assad Regime". Mother Jones. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Militants behind Syria CW attack: Russia

- ^ "Russia Urges Syria To Put Chemical Weapons Under International Control". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 9 September 2013.

- ^ Isachenkov, Vladmir. "Russia To Push Syria To Put Chemical Weapons Under International Control". Huffington Post.

- ^ John Solomon. "US, Russia reach deal on Syria chemical weapons", The Washington Times. 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Syria: Mounting Casualties from Cluster Munitions". Human Rights Watch. 16 March 2013.

- ^ Saad, Waida; Rick, Gladstone (22 February 2013). "Scud Missile Attack Reported in Aleppo". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sevil Küçükkoşum. "Syria fired more than 40 Scud missiles in two months". Hürriyet Daily News.

- ^ Sly, Liz (26 February 2013). "Ballistic missile strikes on Aleppo signal new escalation in Syria war". The Washington Post.

- ^ "U.S. condemns Scud attack in Syria, invites opposition for talks". NBC News. 24 February 2013.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew (1 March 2013). "Syria crisis: Scud missile lands in Iraq". The Guardian.

- ^ "20 dead in Scud missile attack in Syria, activists say". Los Angeles Times. 29 March 2013.

- ^ "NGO: Missile fired on Syria town kills 4 civilians". Al Arabiya. 28 April 2013.

- ^ "Syrian missile kills 26 in village near Aleppo 3 June 2013". France 24. 6 December 2012.

- ^ "Suicide bomber kills 16 in Syrian capital". 8 April 2013.

- ^ "Wider Use of Car Bombs Angers Both Sides in Syrian Conflict". The New York Times. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ^ Mona Mahmood and Robert Booth. "Syrian army may use kamikaze pilots against west, Assad officer claims". The Guardian.

- ^ http://www.smh.com.au/world/syrias-deadly-barrel-bombs-20120901-2573t.html Syria's deadly barrel bombs

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/9512719/Syrian-regime-deploys-deadly-new-weapons-on-rebels.html Syrian regime deploys deadly new weapons on rebels

- ^ BBC, Jonathan Marcus, Barrel bombs show brutality of war; AFP 20 December 2013 AFP report on Aleppo bombing

- ^ Syria rebels say Assad using 'mass-killing weapons' in Aleppo – Israel News, Ynetnews. Ynetnews.com (20 June 1995).

- ^ Dropping Thermobaric Bombs on Residential Areas in Syria_ Nov. 5. 2012 – Syria Videos : Firstpost Topic – Page 1. Firstpost.com.

- ^ Cumming-Bruce, Nick (4 June 2013). "U.N. Panel Reports Increasing Brutality by Both Sides in Syria". The New York Times.

- ^ BBC news, 29 August 2013, BBC News, 30 September 2013 [2]

- ^ a b "Insight: Battered by war, Syrian army creates its own replacement". Reuters. 21 April 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ^ Michael Weiss (17 May 2013). "Rise of the militias". NOW.

- ^ "Syria's Alawite Force Turned Tide for Assad". Wall Street Journal. 26 August 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Syria's civil war: The regime digs in". The Economist. 15 June 2013.

- ^ Adam Heffez (28 November 2013). "Using Women to Win in Syria". Al-Monitor (Eylül). Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ^ a b c Asher, Berman. "Criminalization of the Syrian Conflict". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ a b The Syrian Shabiha and Their State. (PDF).

- ^ Adorno, Esther (8 June 2011). "The Two Homs". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Oweis, Khaled Yacoub (15 September 2011). "Armored Syrian forces storm towns near Turkey border". Amman. Reuters. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- ^ "U.S. blacklists al-Nusra Front fighters in Syria". CNN. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Bashar Al-Assad's transformation". Saudi Gazette. 15 May 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ Holmes, Oliver (15 August 2011). "Assad's Devious, Cruel Plan to Stay in Power By Dividing Syria—And Why It's Working". TNR.

- ^ a b "Analysis: Assad retrenches into Alawite power base". Reuters. 4 May 2011.

- ^ Oweis, Khaled Yacoub (3 February 2012). "Uprising finally hits Syria's "Silk Road" city". Reuters. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Iran and Hezbollah build militia networks in Syria, officials say". The Guardian. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Pro-Assad militia now key to Syrian government’s war strategy". The Miami Herald. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013

- ^ "Drone flight over Israel: Nasrallah's latest surprise". Arab-American News.

- ^ Hirst, David (23 October 2012). "Hezbollah uses its military power in a contradictory manner". The Daily Star. Beirut.

- ^ "Hezbollah fighters, Syrian rebels killed in border fighting". Al Arabiya, 17 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "Hezbollah fighters killed in Syria will 'go to hell,' says former leader". Al Arabiya. 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Barnard, Anne; Saad, Hwaida (19 May 2013). "Hezbollah Aids Syrian Military in a Key Battle". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Anne Barnard, Hania Mourtada (30 April 2013). "Leader of Hezbollah Warns It Is Ready to Come to Syria's Aid". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ "Syrian offensive on Qusayr deepens". Al Jazeera.

- ^ a b c Mroue, Bassem (25 May 2013). "Hezbollah chief says group is fighting in Syria". Associated Press. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21592634-civil-war-neighbouring-syria-putting-ever-greater-strain-lebanons Lebanon: Will it hold together?

- ^ "The long road to Damascus". The Economist. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Syrian opposition groups reach unity deal". USA Today. 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Syrian opposition groups reach unity deal". USA Today. 11 November 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ Jim Muir (12 November 2012). "Syria crisis: Gulf states recognise Syria opposition". BBC. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "The National Coalition of Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces". Local Coordination Committees of Syria. 12 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Defecting troops form 'Free Syrian Army', target Assad security forces". The World Tribune. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Torvov, Daniel (2 December 2011). "Free Syrian Army Partners with Opposition: What's Next for Syria?". International Business Times. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ Blomfield, Adam (21 November 2011). "Syrian rebels strike heart of Damascus". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Syrian rebel leader Salim Idriss admits difficulty of unifying fighters". 7 May 2013.

- ^ "A Syrian solution to civil conflict? The Free Syrian Army is holding talks with Assad's senior staff". The Independent. 29 September 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ "Kerry: Syrian rebels have not been hijacked by extremists". USA Today. 4 September 2013.

- ^ Kelley, Michael (19 September 2013). "A full extremist-to-moderate spectrum of the 100,000 Syrian rebels". Business Insider. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Malas, Nour & Abushakra, Rima (25 September 2013). "Syrian rebel units reject pro-western opposition political leaders". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "As Syrian War Drags On, Jihadists Take Bigger Role". The New York Times. 29 July 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "ICSR Insight: European Foreign Fighters in Syria". 2 April 2013.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (7 January 2014). "Not Just About Us". New York Times. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

Why is it that some 15,000 Arabs and Muslims have flocked to Syria to fight and die for jihadism ...

- ^ "'He was brainwashed': Desperate Belgian father searches for son fighting in Syria". 26 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Syria: the foreign fighters joining the war against Bashar al-Assad". The Guardian. 23 September 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "Libya's Fighters Export Their Revolution to Syria". 27 August 2012.

- ^ "Leading Libyan Islamist met Free Syrian Army opposition group". 27 November 2011.

- ^ "Libya rebels move onto Syrian battlefield". 28 July 2012.

- ^ a b Ghazi, Yasir; Arango, Tim (28 October 2012). "Iraqi Sects Join Battle in Syria on Both Sides". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ "With Official Wink And Nod, Young Saudis Join Syria's Rebels". 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Syria conflict: Why did my Tunisian son join the rebels?". 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Egyptian Fighters Join 'Lesser Jihad' in Syria". 17 April 2013.

- ^ "Spain arrests 'Syria jihadist suspects' in Ceuta". BBC. 21 June 2013.

- ^ "Syrian rebels reject interim government, embrace Sharia". 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Inside Jabhat al Nusra – the most extreme wing of Syria's struggle". 2 December 2012.

- ^ "Qaeda in Iraq confirms Syria's Nusra is part of network". Agence France-Presse. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Al-Nusra Commits to al-Qaida, Deny Iraq Branch 'Merger'". Agence France-Presse. 10 April 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ^ "With wary eye, Syrian rebels welcome Islamists into their ranks". 25 October 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Chulov, Martin (17 January 2013). "Syria crisis: al-Qaida fighters revealing their true colours, rebels say". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ^ Catholic Priest Allegedly Beheaded in Syria by Al-Qaeda-Linked Rebels as Men and Children Take Pictures and Cheer. TheBlaze.com (30 June 2013).

- ^ Gul Tuysuz, Raja Razek, Nick Paton Walsh (6 November 2013). "Al Qaeda-linked group strengthens hold in northern Syria". CNN. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Syria: Harrowing torture, summary killings in secret ISIS detention centres". 19 December 2013. Amnesty International. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ Birke, Sarah (27 December 2013). "How al-Qaeda Changed the Syrian War". New York Review of Books.

Since its appearance last April, ISIS has changed the course of the Syrian war. It has forced the mainstream Syrian opposition to fight on two fronts. It has obstructed aid getting into Syria, and news getting out. And by gaining power, it has forced the US government and its European allies to rethink their strategy of intermittent support to the moderate opposition and rhetoric calling for the ouster of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. After months of shunning Islamist groups in Syria, the Obama administration has now said it may need to talk to the Islamist Front, a new coalition of hard-line rebel groups, in part, because they might prove a buffer against the more extreme ISIS. Ryan Crocker, a former top US State Department official in the Middle East, has told The New York Times that American officials, left with few other options, should quietly start to reengage with the Assad regime. In December, US and Britain suspended non-lethal assistance to rebel groups in northern Syria after one base fell into Islamist hands.

- ^ "Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the situation of human rights in the Syrian Arab Republic" (PDF). UN Human Rights Council. 15 September 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|separator=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Muscati, Samer (14 May 2012). "Syrian Kurds Fleeing to Iraqi Safe Haven". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Blair, Edmund; Saleh, Yasmine (4 July 2012). "Syria opposition rifts give world excuse not to act". Reuters. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ YPG Commander: Kurds Are Bulwark Against Islamic Extremism in Syria. Rudaw.net.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, David D. (9 September 2012). "Syria Criticizes France for Supporting Rebels, as Fears Grow of Islamist Infiltration". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ^ "War in Syria: Clashes ease at Damascus Palestinian refugee camp". Associated Press via Daily News. 20 December 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ Stateless and hapless as ever. The Economist. 17 November 2012.

- ^ a b Nordland, Rod; Mawad, Dalal (30 June 2012). "Palestinians in Syria Are Reluctantly Drawn into Vortex of Uprising". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- ^ "Syria rebels bring fight to pro-Assad Palestinians". The Daily Star. 31 October 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ http://www.maannews.net/eng/ViewDetails.aspx?ID=664216; CBC News, 14 January 2014[3]

- ^ Reuters 14 January 2014,[4]

- ^ "Syria refugees swell Christian community in Turkey".

- ^ 405-819-7955 (5 September 2013). "Jabhat al-Nusra and Other Islamists Briefly Capture Historic Christian Town of Ma'loula – Syria Comment". Joshualandis.com.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ "UN chief slams Syria's crackdown on protests". Al Jazeera. 18 March 2011.

- ^ "Canada condemns violence in Yemen, Bahrain, Syria". Agence France-Presse. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "China and Russia veto UN resolution condemning Syria". BBC. 5 October 2011.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly Resolution 182 session 46 Strengthening of the coordination of humanitarian emergency assistance of the United Nations on 19 December 1991

- ^ United Nations, Syria Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP), http://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/revised-syria-humanitarian-assistance-response-plan-sharp-january. Retrieved 18 September 2013

- ^ UNOCHA, Financial Tracking Service, http://fts.unocha.org/pageloader.aspx?page=emerg-emergencyDetails&emergID=16303. Retrieved 18 September 2013

- ^ "USAID/SYRIA".

- ^ "SYRIAN HUMANITARIAN RELIEF".

- ^ "Iran sending tonnes of flour daily to Syria: report". Agence France-Presse. 3 March 2013.

- ^ Lebovic, Matt (8 July 2013). "Wounded Syrian shuttled to Safed hospital". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Israeli doctors save Syrian lives. ISRAEL21c (26 June 2013).

- ^ Israel may be operating in Syria. GlobalPost (10 April 2013).

- ^ "Humanitarian aid convoy departs to help Syrian refugees". 27 April 2013.

- ^ "WHO warns of Syria disease threat". BBC. 4 June 2013.

- ^ Memmott, Mark (13 November 2013). "As Talks Continue, CIA Gets Some Weapons To Syrian Rebels". National Public Radio. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathon (10 August 2012). "Syria conflict: UK to give extra £5m to opposition groups". BBC. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "France's Hollande hints at arming Syrian rebels". France24. 20 September 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Reuters in Seoul (15 November 2013). "Guardian 15 November 2013". The Guardian.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Syria's War Viewed Almost in Real Time". The Wall Street Journal. 27 September 2013.

- ^ "Watching Syria's War". NYT. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

SOHRwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Violations Documenting Centerwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Violations Documenting Center1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Syrian Martyrs". Free Syria. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "U.N.'s Syria death toll jumps dramatically to 60,000-plus". 3 January 2013.

- ^ "Syria death toll at least 93,000, says UN". BBC News. 13 June 2013.

- ^ "U.N. says Syria death toll has likely surpassed 100,000". Los Angeles Times. 13 June 2013.

- ^ "Syria crisis: Solidarity amid suffering in Homs". BBC. 29 January 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Enders, David (6 November 2012). "Deaths in Syria down from peak; army casualties outpacing rebels'". Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- ^ "400 children killed in Syria unrest". Geneva: Arab News. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Peralta, Eyder (3 February 2012). "Rights Group Says Syrian Security Forces Detained, Tortured Children: The Two-Way". NPR.

- ^ Fahim, Kareem (5 January 2012). "Hundreds Tortured in Syria, Human Rights Group Says". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Fighting Continues in Syria". Arutz Sheva. 16 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ "Syria crisis: Number of refugees rises to 200,000". BBC News. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Syrian Refugees in Lebanon," The New York Times, 5 September 2013

- ^ "Syrian refugee camps in Turkish territory tracked by satellite". Astrium-geo.com.

- ^ "Up to 335,000 people have fled Syria violence: UNHCR". Reuters. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "UN refugee agency says more than 2m have fled Syria". BBC.

- ^ http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/afp/130313/un-must-refer-syria-war-crimes-icc-amnesty

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/16/world/meast/syria-civil-war/index.html

- ^ Heilprin, John. "Syria Massacres: UN Probe Finds 8 Were Perpetrated By Syria Regime, 1 By Rebels". Huffington Post.

- ^ http://www.cbsnews.com/news/8-massacres-by-syria-regime-and-1-by-rebels-since-april-2012-un-war-crimes-report-shows/

- ^ Syria conflict: Women 'targets of abuse and torture', BBC, 26 November 2013.

- ^ http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/middle-east/2013/11/25/Report-rape-used-as-weapon-of-war-against-Syria-women-.html Report: rape used as weapon of war against Syria women

- ^ http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/regions/middle-east/syria/131126/6000-women-raped-during-syrian-conflict 6,000 cases of women raped during Syrian conflict, human rights group says

- ^ "Syria Weighs Its Tactics As Pillars of Its Economy Continue to Crumble". The New York Times. 13 July 2013.

- ^ "Report Shows War's Impact on Syrian Economy – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor.

- ^ Cave, Damein (9 August 2012). "Crime Wave Engulfs Syria as Its Cities Reel From War". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "The ultimate assault: Charting Syria's use of rape to terrorize its people". Women Under Siege. 11 July 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Cunliffe, Emma. "Damage to the Soul: Syria's cultural heritage in conflict". Durham University and the Global Heritage Fund. 1 May 2012.

- ^ Fisk, Robert. "Syria's ancient treasures pulverised". The Independent. 5 August 2012.

- ^ David Batty. "Syrian art smuggled from the midst of civil war to show in London". The Guardian.

- ^ "Syria bombs Lebanon, targeting Syria rebels".

Further reading

- Hinnebusch, Raymond (2012). "Syria: From 'Authoritarian Upgrading' to Revolution?". International Affairs. 88 (1): 95–113. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01059.x.

- International Crisis Group (13 July 2011). "Popular Protest in North Africa and the Middle East (VII): The Syrian Regimes Slow-Motion Suicide" (PDF). Middle East/North Africa Report N°109. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- Landis, Joshua (2012). "The Syrian Uprising of 2011: Why the Asad Regime Is Likely to Survive to 2013". Middle East Policy. 19 (1): 72–84. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.2012.00524.x.

- Lawson, Fred Haley, ed. (1 February 2010). Demystifying Syria. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-654-7.

- Rashdan, Abdelrahman. Syrians Crushed in a Complex International Game. OnIslam.net. 21 March 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Van Dam, Nikolaos (15 July 2011). The Struggle for Power in Syria: Politics and Society under Asad and the Ba'ath Party. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84885-760-8.

- Wright, Robin (2008). Dreams and Shadows: The Future of the Middle East. New York: Penguin Press. pp. 212–261. ISBN 1-59420-111-0.

- Ziadeh, Radwan (2011). Power and Policy in Syria: Intelligence Services, Foreign Relations and Democracy in the Modern Middle East. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-434-5.

External links

- Interviews

- A discussion of the causes of the civil war at the United Nations University for Peace.

- First ever broadcast interview with Jabhat al Nusra founder Abu Mohammed al-Joulani

- Supranational government bodies

- Human rights bodies

- Media

- Syria Conflict at BBC News

- Syrian uprising: A year in turmoil at The Washington Post

- Latest Syria developments at NOW Lebanon

- Syria collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Syria collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Syria news, all the latest and breaking Syria news at The Daily Telegraph

- Syria collected coverage at Al Jazeera English

- The battle for Syria (documentary films). Sources: TV news air footage (video documentary + English subtitles The battle for Syria, official video documentary and the official text of the [5]).VGTRK

- Syrian diary (documentary films). Sources: TV news air footage (video documentary + English subtitles Syrian diary), official video documentary of the [6].VGTRK

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).

- Syrian Civil War

- 2010s civil wars

- 2011 in Syria

- 2012 in Syria

- 2013 in Syria

- Arab Spring by country

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia

- Conflicts in 2011

- Conflicts in 2012

- Conflicts in 2013

- Politics of Syria

- Protests in Syria

- Rebellions in Syria

- Wars involving Hezbollah

- Wars involving Iran

- Wars involving Qatar

- Wars involving Saudi Arabia

- Wars involving Turkey

- Wars involving Syria