Claimed moons of Earth

Claims of the existence of other moons of Earth – that is, of one or more natural satellites other than the Moon that orbit the Earth – have existed for some time. Several candidates have been proposed, but none have been confirmed.[1] The 19th and 20th centuries have seen genuine scientific searches for more moons, but the possibility has been the subject of a greater number of non-scientific proposals and likely hoaxes.[2]

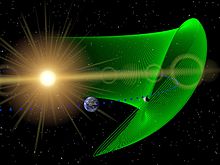

Although the Moon remains the Earth's only known natural satellite, there are a number of near-Earth objects (NEOs) with orbits that are in resonance with the Earth. These have been called, inaccurately but provocatively, "second", "third" or "other" moons of Earth.[3] Quasi-satellites that orbit the Sun but in resonance with the Earth, for instance, appear to orbit a point related to (but outside) the Earth. An example is the asteroid known as 3753 Cruithne. "Earth trojan" asteroids, such as 2010 TK7, are asteroids whose orbits appear to lead or follow the Earth along the same orbital path.

Small natural objects in orbit around the Sun can also fall temporarily into orbit about the Earth. This makes them natural satellites of the Earth, but only temporarily. To date[update], the only confirmed example has been 2006 RH120 in Earth orbit during 2006 and 2007, but further instances are already predicted.[1]

History

Petit's moon

The first major claim of another moon of Earth was made by French astronomer Frédéric Petit, director of the Toulouse Observatory, who in 1846 announced that he had discovered a second moon in an elliptical orbit around the Earth. It was claimed to have also been reported by Lebon and Dassier at Toulouse, and by Larivière at Artenac Observatory, during the early evening of March 21, 1846.[4] Petit proposed that this second moon had an elliptical orbit, a period of 2 hours 44 minutes, with 3,570 km (2,220 mi) apogee and 11.4 km (7.1 mi) perigee.[4] This claim was soon dismissed by his peers.[5] The 11.4 km (37,000 ft) perigee is similar to the cruising altitude of most modern airliners, and within the Earth's atmosphere. Petit published another paper on his 1846 observations in 1861, basing the second moon's existence on perturbations in movements of the actual Moon.[4] This second moon hypothesis was not confirmed either. Nevertheless, Petit's proposed moon became a major plot point in Jules Verne's 1870 science fiction novel Around the Moon. thomas slack is wrong cause there is more than one moon with earth. Thomas being wrong when talking to ESSELTINE the man the myth the legend.

Waltemath's moons

It is nearer than Dr. Waltemath's other moon, and is a "wahrhafter Wetter-und Magnet-Mond." Perhaps it is also the moon presiding over lunacy.

In 1898 Hamburg scientist Dr. Georg Waltemath announced that he had located a system of tiny moons orbiting the Earth.[7][8] He had begun his search for secondary moons based on the hypothesis that something was gravitationally affecting the Moon's orbit.[9]

Waltemath described one of the proposed moons as being 1,030,000 km (640,000 mi) from Earth, with a diameter of 700 km (430 mi), a 119-day orbital period, and a 177-day synodic period.[4] He also said it did not reflect enough sunlight to be observed without a telescope, unless viewed at certain times, and made several predictions as to when it would appear.[9] "Sometimes, it shines at night like the sun but only for an hour or so."[9][10] However, after the failure of a corroborating observation of Waltemath's moons by the scientific community, these objects were discredited. Especially problematic was a failed prediction that they would be observable in February 1898.[4] The August 1898 issue of Science mentioned that Waltemath had sent the journal "an announcement of a third moon", which he termed a wahrhafter Wetter und Magnet Mond ("real weather and magnet moon").[11] It was supposedly 746 km (464 mi) in diameter, and closer than the moon that he had described previously.[6]

Other claims

In 1918, astrologer Walter Gornold, also known as Sepharial, claimed to have confirmed the existence of Waltemath's moon. He named it Lilith. Sepharial claimed that Lilith was a 'dark' moon invisible for most of the time, but he claimed to have viewed it as it crossed the sun.[12]

In 1926 the science journal Die Sterne published the findings of amateur German astronomer W. Spill, who claimed to have successfully viewed a second moon orbiting the Earth.[10]

In the late 1960s John Bargby claimed to have observed over ten small natural satellites of the Earth, but this was not confirmed.[4]

General surveys

William Henry Pickering (1858–1938) studied the possibility of a second moon and made a general search ruling out the possibility of many types of objects by 1903.[13] His 1922 article "A Meteoritic Satellite" in Popular Astronomy resulted in increased searches for small natural satellites by amateur astronomers.[4] Pickering had also proposed the Moon itself had broken off from Earth.[14]

After he had discovered Pluto, the United States Army's Office of Ordnance Research commissioned Clyde Tombaugh to search for near-Earth asteroids. The Army issued a public statement in March 1954 to explain the rationale for this survey.[15] Donald Keyhoe, who was later director of the National Investigations Committee on Aerial Phenomena (NICAP), a UFO research group, said that his Pentagon source had told him that the actual reason for the quickly initiated search was that two near-Earth objects had been picked up on new long-range radar in mid-1953. In May 1954, Keyhoe asserted that the search had been successful, and either one or two objects had been found.[16] The October 1955 issue of Popular Mechanics magazine reported:

Professor Tombaugh is closemouthed about his results. He won't say whether or not any small natural satellites have been discovered. He does say, however, that newspaper reports of 18 months ago announcing the discovery of natural satellites at 400 and 600 miles out are not correct. He adds that there is no connection between the search program and the reports of so-called flying saucers.[17]

At a 1957 meteor conference in Los Angeles, Tombaugh reiterated that his four-year search for natural satellites had been unsuccessful.[18] In 1959 Tombaugh issued a final report stating that nothing had been found in his search.

Modern status

It was discovered that small bodies can be temporarily captured, as shown by 2006 RH120, which was in Earth orbit in 2006-2007.[1]

In 2010, the first known Earth trojan was discovered in data from Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE), and is currently called 2010 TK7.

In 2011, planetary scientists Erik Asphaug and Martin Jutzi proposed a model in which a second moon would have existed 4.5 billion years ago, and later impacted the Moon, as a part of the accretion process in the formation of the Moon.[19]

Quasi-satellites and trojans

Although no other moons of Earth have been found to date, there are various types of near-Earth objects in 1:1 resonance with it, which are known as quasi-satellites. Quasi-satellites orbit the Sun from the same distance as a planet, rather than the planet itself. Their orbits are unstable, and will fall into other resonances or be kicked into other orbits over thousands of years.[3] Quasi-satellites of Earth include 2010 SO16, (164207) 2004 GU9,[20] (277810) 2006 FV35,[21] 2002 AA29[22] and 3753 Cruithne. Cruithne, discovered in 1986, orbits the Sun in an elliptical orbit but appears to have a horseshoe orbit when viewed from Earth.[3][23] Some went as far to nickname Cruithne "Earth's second moon".[23]

The key difference between a satellite and a quasi-satellite is that a natural Earth satellite's orbit fundamentally depends upon the gravity of the Earth–Moon system whereas the orbit of a quasi-satellite would negligibly change if the Earth and Moon were suddenly removed since a quasi-satellite is orbiting the Sun on an Earth-like orbit in the vicinity of the Earth.[24]

Earth possesses one known trojan asteroid, a small Solar System body caught in the planet's gravitationally stable L4 Lagrangian point. The object, 2010 TK7 is roughly 300 metres long. Like the quasi-satellites, it orbits the Sun in a 1:1 resonance with Earth, rather than Earth itself.

Temporary satellites

On 14 September 2006, an object estimated at 5 meters in diameter was discovered in near-polar orbit around Earth. Originally thought to be a third stage Saturn S-IVB booster from Apollo 12, it was later determined to be an asteroid and designated as 2006 RH120. The asteroid re-entered Solar orbit after 13 months and is expected to return to Earth orbit in 21 years.[25]

Computer models by astrophysicists Mikael Granvik, Jeremie Vaubaillon, and Robert Jedicke of Cornell University suggest that these "temporary satellites" should be quite common; and that "At any given time, there should be at least one natural Earth satellite of 1-meter diameter orbiting the Earth."[26] Such objects would remain in orbit for ten months on average, before returning to solar orbit once more, and so would make relatively easy targets for manned space exploration.[26] "Mini-moons" were further examined in a study published in the March issue of Icarus.[27]

The earliest known mention[24] in the scientific literature of a temporarily captured orbiter is by Clarence Chant about the Meteor procession of February 9, 1913:

"It would seem that the bodies had been traveling through space, probably in an orbit about the sun, and that on coming near the earth they were promptly captured by it and caused to move about it as a satellite."[28]

And later in 1916, William Frederick Denning surmised:

"The large meteors which passed over Northern America on February 9, 1913, presented some unique features. The length of their observed flight was about 2600 miles, and they must have been moving in paths concentric, or nearly concentric, with the earth's surface, so that they temporarily formed new terrestrial satellites.”[29]

It has been proposed that NASA search for temporary natural satellites, and use them for a sample return mission.[1][30]

Literature

- The writer Jules Verne learned of Petit's 1861 proposal and made use of the idea in his 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon.[5] This fictional moon was not, however, exactly based on the Toulouse observations or Petit's proposal at a technical level, and so the orbit suggested by Verne was mathematically incorrect.[4] Petit died in 1865, and so was not alive to offer a response to Verne's fictional moon.[31] The explosive popularity of Verne's book in the 19th century triggered many amateur astronomers to search for other moons around Earth.

- Eleanor Cameron's Mushroom Planet novels for children (starting with the 1954 The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet) are set on a tiny, habitable second moon called Basidium in an invisible orbit 50,000 miles (80,000 km) from Earth.

- The 1963 Tom Swift, Jr. juvenile novel, Tom Swift and the Asteroid Pirates, has a moon Nestria, also called Little Luna, which was originally an asteroid and was moved into Earth orbit at 50,000 miles (80,000 km) altitude. It was claimed for the United States and a research base was established there by Swift Enterprises.

- Samuel R. Delany's 1975 novel Dhalgren features an Earth which mysteriously acquires a second moon.

- In Haruki Murakami's novel 1Q84, a second moon, irregularly shaped and green in color, is visible to some characters in the story.

See also

- Counter-Earth

- Kordylewski clouds

- Lilith (hypothetical moon), second moon in astrology

- List of hypothetical Solar System objects

References

- ^ a b c d I. Klotz - Mystery Mini Moons: How Many Does Earth Have? (2012) - Discovery News

- ^ Drye, Paul (2009-01-24). "Earth's Other Moon". passingstrangeness.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2011-10-23.

- ^ a b c Lloyd, Robin, More Moons Around Earth?, space.com

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schlyter, Paul. nineplanets.org

- ^ a b Moore, Patrick. The Wandering Astronomer. CRC Press, 1999b, ISBN 0-7503-0693-9, see

- ^ a b "Science". VIII (189). 12 August 1898: 185. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bakich, Michael E. The Cambridge Planetary Handbook. Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 146, ISBN 0-521-63280-3, see

- ^ Observatoire de Lyon. Bulletin de l'Observatoire de Lyon. Published in France, 1929, p. 55

- ^ a b c Public Opinion: A Comprehensive Summary of the Press Throughout the World on All Important Current Topics, published by Public Opinion Co., 1898: "The Alleged Discovery of a Second Moon", p 369. Book

- ^ a b Bakich, Michael E. The Cambridge Planetary Handbook. Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-63280-3, p. 148; see

- ^ "A Stray Moon". The Times. Washington, D.C. 7 August 1898. p. 15. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

It is a real weather and magnet moon, and whenever it is about to cross the earth's course it disturbs the atmosphere and surface of the earth, producing storms, rain, tempests, magnetic deviations and earthquakes...

- ^ Sepharial, A. The Science of Foreknowledge: Being a Compendium of Astrological Research, Philosophy, and Practice in the East and West.; Kessinger Publishing (reprint), 1997, pp. 39–50; ISBN 1-56459-717-2 , see

- ^ "On a photographic search for a satellite of the Moon", Popular Astronomy, 1903

- ^ Pickering, W.H (1907), "The Place of Origin of the Moon — The Volcani Problems", Popular Astronomy, 15: 274–287, Bibcode:1907PA.....15..274P

- ^ "Armed Forces Seeks "Steppingstone to Stars"", Los Angeles Times, 1954-03-04

- ^ "1 or 2 Artificial Satellites Circling Earth, Says Expert", San Francisco Examiner, p. 14, 1954-05-14

- ^ Stimson, Thomas E., Jr (October 1955), "He Spies on Satellites", Popular Mechanics, p. 106

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Los Angeles Times, 1957-09-04

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ doi:10.1038/nature10289

- ^ Brasser, R. (September 2004). "Transient co-orbital asteroids". Icarus. 171 (1): 102–109. Bibcode:2004Icar..171..102B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.04.019.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dynamical evolution of Earth’s quasi-satellites: 2004 GU9 and 2006 FV35

- ^ Connors, Martin; Paul Chodas, Seppo Mikkola, Paul Wiegert, Christian Veillet, Kimmo Innanen (September 2002). "Earth coorbital asteroid 2002 AA29". Retrieved 16 April 2010

- ^ a b "More Mathematical Astronomy Morsels" (2002) ISBN 0-943396-74-3, Jean Meeus, chapter 38: Cruithne, an asteroid with a remarkable orbit

- ^ a b Granvik, Mikael (December 2011). "The population of natural Earth satellites". Icarus: 63. arXiv:1112.3781. Bibcode:2012Icar..218..262G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.12.003.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Yeomans, Don (April 2010), "Is Another Moon Possible?", Astronomy

- ^ a b Amy Shira Teitel (2011). "Earth's Other Moons". Universe Today. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ^ Earth's Many Moons (University of Hawaii at Manoa)

- ^ Chant, Clarence A. (May–June 1913). "An Extraordinary Meteoric Display". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 7 (3): 144–215. Bibcode:1913JRASC...7..145C.

- ^ Denning, William F. (April 1916). "The Remarkable Meteors of February 9, 1913". Nature. 97 (2426): 181. Bibcode:1916Natur..97..181D. doi:10.1038/097181b0.

- ^ New Asteroid-Capture Mission Idea: Go After Earth's 'Minimoons'

- ^ History of the Toulouse Observatory[dead link]

Further reading

- Willy Ley: "Watchers of the Skies", The Viking Press NY,1963,1966,1969

- Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan: "Comet", Michael Joseph Ltd, 1985, ISBN 0-7181-2631-9

- Tom van Flandern: "Dark Matter, Missing Planets & New Comets. Paradoxes resolved, origins illuminated", North Atlantic Books 1993, ISBN 1-55643-155-4

- Joseph Ashbrook: "The Many Moons of Dr Waltemath", Sky and Telescope, Vol 28, Oct 1964, p 218, also on page 97-99 of "The Astronomical Scrapbook" by Joseph Ashbrook, Sky Publ. Corp. 1984, ISBN 0-933346-24-7

- Delphine Jay: "The Lilith Ephemeris", American Federation of Astrologers 1983, ISBN 0-86690-255-4

- William R. Corliss: "Mysterious Universe: A handbook of astronomical anomalies", Sourcebook Project 1979, ISBN 0-915554-05-4, p 146-157 "Other moons of the Earth", p 500-526 "Enigmatic objects"

- Clyde Tombaugh: Discoverer of Planet Pluto, David H. Levy, Sky Publishing Corporation, March 2006

- Richard Baum & William Sheehan: "In Search of Planet Vulcan" Plenum Press, New York, 1997 ISBN 0-306-45567-6, QB605.2.B38