Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney MRIA | |

|---|---|

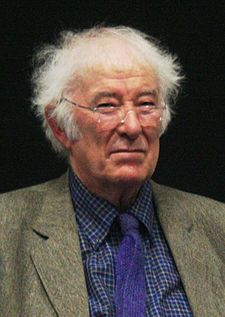

Seamus Heaney (2009) | |

| Born | 13 April 1939 Castledawson, Northern Ireland |

| Died | 30 August 2013 (aged 74) Dublin, Ireland |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright, translator |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Period | 1966–2013 |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Marie Devlin (1965–2013)[1][2] |

| Children | |

Seamus Justin Heaney, MRIA (/ˈʃeɪməs ˈhiːni/; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright, translator and lecturer, and the recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.[1][2] In the early 1960s, he became a lecturer in Belfast after attending university there and began to publish poetry. He lived in Sandymount, Dublin, from 1972 until his death.[2][4][5]

Heaney was a professor at Harvard from 1981 to 1997 and its Poet in Residence from 1988 to 2006. From 1989 to 1994 he was also the Professor of Poetry at Oxford and in 1996 was made a Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et Lettres. Other awards that he received include the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize (1968), the E. M. Forster Award (1975), the PEN Translation Prize (1985), the Golden Wreath of Poetry (2001), T. S. Eliot Prize (2006) and two Whitbread Prizes (1996 and 1999).[6][7] In 2012, he was awarded the Lifetime Recognition Award from the Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry. His literary papers are held by the National Library of Ireland.

Robert Lowell called him "the most important Irish poet since Yeats" and many others, including the academic John Sutherland, have echoed the sentiment that he was "the greatest poet of our age".[6][7] Robert Pinsky has stated that "with his wonderful gift of eye and ear Heaney has the gift of the story-teller".[8] Upon his death in 2013, The Independent described him as "probably the best-known poet in the world".[9]

Early life

From Mid-Term Break

Wearing a poppy bruise on the left temple,

He lay in the four foot box as in a cot.

No gaudy scars, the bumper knocked him clear.

A four foot box, a foot for every year.

Death of a Naturalist (1966)

Heaney was born on 13 April 1939, at the family farmhouse called Mossbawn,[4] between Castledawson and Toomebridge in Northern Ireland; he was the first of nine children. In 1953, his family moved to Bellaghy, a few miles away, which is now the family home. His father, Patrick Heaney (d. October 1986),[10] was the eighth child of ten born to James and Sarah Heaney.[11] Patrick was a farmer, but his real commitment was to cattle-dealing, to which he was introduced by the uncles who had cared for him after the early death of his own parents.[12]

Heaney's mother, Margaret Kathleen McCann (1911–1984),[13] who bore nine children,[14] came from the McCann family,[3] whose uncles and relations were employed in the local linen mill, and whose aunt had worked as a maid for the mill owner's family. Heaney commented on the fact that his parentage thus contained both the Ireland of the cattle-herding Gaelic past and the Ulster of the Industrial Revolution; he considered this to have been a significant tension in his background. Heaney initially attended Anahorish Primary School, and when he was twelve years old, he won a scholarship to St. Columb's College, a Roman Catholic boarding school situated in Derry. Heaney's brother, Christopher, was killed in a road accident at the age of four while Heaney was studying at St. Columb's. The poems "Mid-Term Break" and "The Blackbird of Glanmore" focus on his brother's death.[15]

Career

1957–69

From "Digging"

My grandfather cut more turf in a day

Than any other man on Toner's bog.

Once I carried him milk in a bottle

Corked sloppily with paper. He straightened up

To drink it, then fell to right away

Nicking and slicing neatly, heaving sods

Over his shoulder, going down and down

For the good turf. Digging.

The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap

Of soggy peat, the curt cuts of an edge

Through living roots awaken in my head.

But I've no spade to follow men like them.

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I'll dig with it.

Template:Details3 In 1957, Heaney traveled to Belfast to study English Language and Literature at Queen's University Belfast. During his time in Belfast, he found a copy of Ted Hughes's Lupercal, which spurred him to write poetry. "Suddenly, the matter of contemporary poetry was the material of my own life," he said.[6] He graduated in 1961 with a First Class Honours degree. During teacher training at St Joseph's Teacher Training College in Belfast (now merged with St Mary's, University College), Heaney went on a placement to St Thomas' secondary Intermediate School in west Belfast. The headmaster of this school was the writer Michael McLaverty from County Monaghan, who introduced Heaney to the poetry of Patrick Kavanagh.[16][17] With McLaverty's mentor-ship, Heaney first started to publish poetry, beginning in 1962. Hillan describes how McLaverty was like a foster father to the younger Belfast poet.[18] In the introduction to McLaverty's Collected works, Heaney summarised the poet's contribution and influence: "His voice was modestly pitched, he never sought the limelight, yet for all that, his place in our literature is secure."[19] Heaney's poem Fosterage, in the sequence Singing School from North (1975) is dedicated to him.

In 1963, Heaney became a lecturer at St Joseph's and in the spring of 1963, after contributing various articles to local magazines, he came to the attention of Philip Hobsbaum, then an English lecturer at Queen's University. Hobsbaum was to set up a Belfast Group of local young poets (to mirror the success he had with the London group) and this would bring Heaney into contact with other Belfast poets such as Derek Mahon and Michael Longley. In August 1965 he married Marie Devlin, a school teacher and native of Ardboe, County Tyrone. (Devlin is a writer herself and, in 1994, published Over Nine Waves, a collection of traditional Irish myths and legends.) Heaney's first book, Eleven Poems, was published in November 1965 for the Queen's University Festival. In 1966, Faber and Faber published his first major volume, called Death of a Naturalist. This collection met with much critical acclaim and went on to win several awards, the Gregory Award for Young Writers and the Geoffrey Faber Prize.[17] Also in 1966, he was appointed as a lecturer in Modern English Literature at Queen's University Belfast and his first son, Michael, was born. A second son, Christopher, was born in 1968. That same year, with Michael Longley, Heaney took part in a reading tour called Room to Rhyme, which led to much exposure for the poet's work. In 1969, his second major volume, Door into the Dark, was published.

1970–84

Template:Details3 After a spell as guest lecturer at the University of California, Berkeley, he returned to Queen's University in 1971. In 1972, Heaney left his lectureship at Belfast and moved to Dublin in the Republic of Ireland, working as a teacher at Carysfort College. In the same year, Wintering Out was published, and over the next few years Heaney began to give readings throughout Ireland, Great Britain and the United States. In 1975, Heaney published his fourth volume, North. Also published was Stations. He became Head of English at Carysfort College in Dublin in 1976. His next volume, Field Work, was published in 1979. Selected Poems 1965-1975 and Preoccupations: Selected Prose 1968–1978 were published in 1980. When Aosdána, the national Irish Arts Council, was established in 1981, Heaney was among those elected into its first group (he was subsequently elected a Saoi, one of its five elders and its highest honour, in 1997).[20] Also in 1981, he left Carysfort to become visiting professor at Harvard University, where he was affiliated with Adams House. He was awarded two honorary doctorates, from Queen's University and from Fordham University in New York City (1982). At the Fordham commencement ceremony in 1982, Heaney delivered the commencement address in a 46-stanza poem entitled Verses for a Fordham Commencement.

As he was born and educated in Northern Ireland, Heaney felt the need to emphasise that he was Irish and not British.[21] Following the success of the Field Day Theatre Company's production of Brian Friel's Translations, Heaney joined the company's expanded Board of Directors in 1981, when the company's founders Brian Friel and Stephen Rea decided to make the company a permanent group.[22] In autumn 1984, his mother, Margaret, died.[10][23]

1985–99

Heaney was Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University (formerly Visiting Professor) 1985–1997 and the Ralph Waldo Emerson Poet in Residence at Harvard 1998–2006.[24] In 1986, Heaney received a Litt.D. from Bates College. His father, Patrick, died in October the same year.[10] In 1988, a collection of critical essays called The Government of the Tongue was published.

In 1989, Heaney was elected Professor of Poetry at the University of Oxford, which he held for a five-year term to 1994. The chair does not require residence in Oxford, and throughout this period he was dividing his time between Ireland and the United States. He also continued to give public readings; so well attended and keenly anticipated were these events that those who queued for tickets with such enthusiasm were sometimes dubbed "Heaneyboppers", suggesting an almost teenybopper fanaticism on the part of his supporters.[25] Heaney was named an Honorary Patron of the University Philosophical Society, Trinity College, Dublin, and was elected an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature (1991).[26] In 1993, Heaney guest-edited The Mays Anthology, a collection of new writing from students at the University of Oxford and University of Cambridge. In 1990, The Cure at Troy, a play based on Sophocles's Philoctetes,[27] was published to much acclaim, followed by Seeing Things in 1991.

Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995 for what the Nobel committee described as "works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past".[28] He was on holiday in Greece with his wife when the news broke and no one, not even journalists or his own children, could find him until he appeared at Dublin Airport two days later, though an Irish television camera traced him to Kalamata. Asked how it felt having his name added to the Irish Nobel pantheon featuring William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and Samuel Beckett, Heaney responded: "It's like being a little foothill at the bottom of a mountain range. You hope you just live up to it. It's extraordinary." He and Marie were immediately whisked straight from the airport to Áras an Uachtaráin for champagne with the then President Mary Robinson.[29]

Heaney's 1996 collection The Spirit Level won the Whitbread Book of the Year Award and repeated the success with the release of Beowulf: A New Translation.[30]

In 1996, Heaney was elected a Member of the Royal Irish Academy, and admitted in 1997.[31] In the same year, Heaney was elected Saoi of Aosdána.[32]

2000s

Template:Details3 In 2000, Heaney was awarded an honorary doctorate and delivered the commencement address at the University of Pennsylvania.[33] In 2002, Heaney was awarded an honorary doctorate from Rhodes University and delivered a public lecture on "The Guttural Muse".[34]

In 2003, the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry was opened at Queen's University Belfast. It houses the Heaney Media Archive, a record of Heaney's entire oeuvre, along with a full catalogue of his radio and television presentations.[35] That same year Heaney, decided to lodge a substantial portion of his literary archive at Emory University, as a memorial to the work of William M. Chace, the university's recently retired president.[36][37] The Emory papers represented the largest repository of Heaney's work (1964–2003), donated to build their large existing archive from Irish writers including Yeats, Paul Muldoon, Ciaran Carson, Michael Longley and other members of the The Belfast Group.[38]

In 2003, when asked if there was any figure in popular culture who aroused interest in poetry and lyrics, Heaney praised rap artist Eminem, saying "He has created a sense of what is possible. He has sent a voltage around a generation. He has done this not just through his subversive attitude but also his verbal energy."[39][40] He composed the poem "Beacons of Bealtaine" for the 2004 EU Enlargement. The poem was read by Heaney at a ceremony for the twenty-five leaders of the enlarged European Union arranged by the Irish EU presidency.

In August 2006, Heaney suffered a stroke. Although he recovered and joked, "Blessed are the pacemakers" when fitted with a heart monitor,[41] he cancelled all public engagements for several months.[42] He was in County Donegal at the time on the occasion of the 75th birthday of Anne Friel, playwright Brian Friel's wife.[3][43] He read the works of Henning Mankell, Donna Leon and Robert Harris while in hospital, and was visited at the time by Bill Clinton.[3][44]

Heaney's District and Circle won the 2006 T. S. Eliot Prize.[45] In 2008, he became artist of honour in Østermarie, Denmark and the Seamus Heaney Stræde (street) was named after him. In 2009, Heaney was presented with an Honorary-Life Membership award from the UCD Law Society, in recognition of his remarkable role as a literary figure.[46] Faber and Faber published Dennis O'Driscoll's book Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney in 2008; this has been described as the nearest thing to an autobiography of Heaney.[47] In 2009, Heaney was awarded the David Cohen Prize for Literature. He spoke at the West Belfast Festival 2010 in celebration of his mentor, the poet and novelist Michael MacLaverty, who had helped Heaney to first publish his poetry.[48]

2010s

In 2010, Faber published Human Chain, Heaney's twelfth collection. Human Chain was awarded the Forward Poetry Prize for Best Collection, one of the only major poetry prizes Heaney had never previously won, despite having been twice shortlisted.[49][50] The book, published 44 years after the poet's first, was inspired in part by Heaney's stroke in 2006 which left him "babyish" and "on the brink". Poet and Forward judge Ruth Padel described the work as "a collection of painful, honest and delicately weighted poems...a wonderful and humane achievement".[49] Writer Colm Tóibín described Human Chain as "his best single volume for many years, and one that contains some of the best poems he has written... is a book of shades and memories, of things whispered, of journeys into the underworld, of elegies and translations, of echoes and silences."[51] In October 2010, the collection was shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize.

Heaney was named one of "Britain's top 300 intellectuals" by The Observer in 2011, though the newspaper later published a correction acknowledging that "several individuals who would not claim to be British" had been featured, of which Heaney was one.[52] That same year, he contributed translations of Old Irish marginalia for Songs of the Scribe, an album by Traditional Singer in Residence of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry, Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin.[53]

In December 2011, he donated his personal literary notes to the National Library of Ireland.[54] Even though he admitted he would likely have earned a fortune by auctioning them, Heaney personally packed up the boxes of notes and drafts and, accompanied by his son Michael, delivered them to the National Library.[55]

In June 2012, Heaney accepted the Griffin Trust for Excellence in Poetry's Lifetime Recognition Award and gave a 12 minute speech in honour of the award.[56]

Death

Heaney died in the Blackrock Clinic in Dublin on 30 August 2013, aged 74, following a short illness.[57][58][59] After a fall outside a restaurant in Dublin,[59] he entered hospital the night before his death for a medical procedure but died at 7:30 the following morning before it took place. His funeral was held in Donnybrook, Dublin, on the morning of 2 September 2013, and he was buried in the evening at his home village of Bellaghy, in the same graveyard as his parents, young brother, and other family members.[57][60] His son Michael revealed at the funeral mass that his father's final words, "Noli timere", were texted to his wife, Marie, minutes before he died.[41][61]

A crowd of 81,553 spectators applauded Heaney for three minutes at an All-Ireland Gaelic football semi-final match on September 1.[62] His funeral was broadcast live the following day on RTÉ television and radio, and was streamed internationally at RTÉ's website, while RTÉ Radio 1 Extra transmitted a continuous broadcast, from 8 a.m. to 9:15 p.m. on the day of the funeral, of his Collected Poems album, recorded by Heaney himself in 2009.[63] His poetry collections sold out rapidly in Irish bookshops immediately following his death.[64]

Many tributes were paid to Heaney. President Michael D. Higgins said: "...we in Ireland will once again get a sense of the depth and range of the contribution of Seamus Heaney to our contemporary world, but what those of us who have had the privilege of his friendship and presence will miss is the extraordinary depth and warmth of his personality...Generations of Irish people will have been familiar with Seamus' poems. Scholars all over the world will have gained from the depth of the critical essays, and so many rights organisations will want to thank him for all the solidarity he gave to the struggles within the republic of conscience."[65] Higgins also appreared live from Áras an Uachtaráin on the Nine O'Clock News in a five-minute segment in which he paid tribute to Heaney.[66]

Bill Clinton, former President of the United States, said: "Both his stunning work and his life were a gift to the world. His mind, heart, and his uniquely Irish gift for language made him our finest poet of the rhythms of ordinary lives and a powerful voice for peace...His wonderful work, like that of his fellow Irish Nobel Prize winners Shaw, Yeats, and Beckett, will be a lasting gift for all the world."[67] José Manuel Barroso, European Commission president, said: "I am greatly saddened today to learn of the death of Seamus Heaney, one of the great European poets of our lifetime...The strength, beauty and character of his words will endure for generations to come and were rightly recognised with the Nobel Prize for Literature."[67] Harvard University issued a statement: "We are fortunate and proud to have counted Seamus Heaney as a revered member of the Harvard family. For us, as for people around the world, he epitomised the poet as a wellspring of humane insight and artful imagination, subtle wisdom and shining grace. We will remember him with deep affection and admiration."[67]

Poet Michael Longley, a close friend of Heaney, said: "I feel like I've lost a brother".[68] Thomas Kinsella was shocked but John Montague said he had known for some time the poet was not well.[69] Playwright Frank McGuinness called Heaney "the greatest Irishman of my generation: he had no rivals".[70] Colm Tóibín wrote: "In a time of burnings and bombings Heaney used poetry to offer an alternative world".[71] Gerald Dawe said he was "like an older brother who encouraged you to do the best you could do".[70] Theo Dorgan said "[Heaney's] work will pass into permanence. Everywhere I go there is real shock at this. Seamus was one of us", while Heaney's publisher Faber and Faber noted that "his impact on literary culture is immeasurable."[72] Playwright Tom Stoppard said, "Seamus never had a sour moment, neither in person nor on paper".[70] Andrew Motion, a former UK Poet Laureate and friend of Heaney, called him "a great poet, a wonderful writer about poetry, and a person of truly exceptional grace and intelligence".[68]

Work

From "Joy Or Night":

In order that human beings bring about the most radiant conditions for themselves to inhabit, it is essential that the vision of reality which poetry offers should be transformative, more than just a printout of the given circumstances of its time and place. The poet who would be most the poet has to attempt an act of writing that outstrips the conditions even as it observes them.

Upon his death, Heaney's books made up two-thirds of the sales of living poets in the UK.[6] His work often deals with the local surroundings of Ireland, particularly in Northern Ireland, where he was born. Speaking of his early life and education, he commented "I learned that my local County Derry experience, which I had considered archaic and irrelevant to 'the modern world' was to be trusted. They taught me that trust and helped me to articulate it."[73] Death of a Naturalist (1966) and Door into the Dark (1969) mostly focus on the detail of rural, parochial life.[73]

Allusions to sectarian difference, widespread in Northern Ireland through his lifetime, can be found in his poems. His books Wintering Out (1973) and North (1975) seek to interweave commentary on 'The Troubles' with a historical context and wider human experience.[73] While some critics accused Heaney of being "an apologist and a mythologizer" of the violence, Blake Morrison suggests the poet "has written poems directly about the Troubles as well as elegies for friends and acquaintances who have died in them; he has tried to discover a historical framework in which to interpret the current unrest; and he has taken on the mantle of public spokesman, someone looked to for comment and guidance... Yet he has also shown signs of deeply resenting this role, defending the right of poets to be private and apolitical, and questioning the extent to which poetry, however 'committed,' can influence the course of history."

Shaun O'Connell in the New Boston Review notes that "those who see Seamus Heaney as a symbol of hope in a troubled land are not, of course, wrong to do so, though they may be missing much of the undercutting complexities of his poetry, the backwash of ironies which make him as bleak as he is bright."[73] O'Connell notes in his Boston Review critique of Station Island: "Again and again Heaney pulls back from political purposes; despite its emblems of savagery, Station Island lends no rhetorical comfort to Republicanism. Politic about politics, Station Island is less about a united Ireland than about a poet seeking religious and aesthetic unity".[74]

Heaney is described by critic Terry Eagleton as "an enlightened cosmopolitan liberal",[75] refusing to be drawn. Eagleton suggests: "When the political is introduced... it is only in the context of what Heaney will or will not say."[76] Reflections on what Heaney identifies as "tribal conflict",[76] favour the description of people's lives and their voices, drawing out the 'psychic landscape'. His collections often recall the assassination of his family members and close friends, lynchings and bombings. Colm Tóibín wrote, "throughout his career there have been poems of simple evocation and description. His refusal to sum up or offer meaning is part of his tact."[51]

Heaney published “Requiem for the Croppies”, a poem that commemorates the Irish rebels of 1798, on the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising. He read the poem to both Catholic and Protestant audiences in Ireland. He commented "To read ‘'Requiem for the Croppies'’ wasn't to say ‘up the IRA’ or anything. It was silence-breaking rather than rabble-rousing.”[77] He stated “You don't have to love it. You just have to permit it.”

He turned down the offer of laureateship of the United Kingdom partly for political reasons, commenting "I’ve nothing against the Queen personally: I had lunch at the Palace once upon a time". He stated that his "cultural starting point" was "off centre". A much-quoted statement was when he objected to being included in The Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry (1982), despite being born in Northern Ireland. His response to being included in the British anthology was delivered in his poem, An Open Letter:

"Don't be surprised if I demur, for, be advised

My passport's green.

No glass of ours was ever raised

To toast The Queen."[77]

He was concerned, as a poet and a translator, with the English language itself as it is spoken in Ireland but also as spoken elsewhere and in other times; the Anglo-Saxon influences in his work and study are strong. Critic W. S. Di Piero noted "Whatever the occasion, childhood, farm life, politics and culture in Northern Ireland, other poets past and present, Heaney strikes time and again at the taproot of language, examining its genetic structures, trying to discover how it has served, in all its changes, as a culture bearer, a world to contain imaginations, at once a rhetorical weapon and nutriment of spirit. He writes of these matters with rare discrimination and resourcefulness, and a winning impatience with received wisdom."[73] Heaney's first translation came with the Irish lyric poem "Buile Suibhne", published as Sweeney Astray: A Version from the Irish (1984), a character and connection taken up in Station Island (1984). Heaney's prize-winning translation of Beowulf (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000, Whitbread Book of the Year Award) was seen as ground-breaking in its use of modern language melded with the original Anglo-Saxon 'music'.[73]

His works of drama includes The Cure at Troy: A Version of Sophocles' Philoctetes (1991). Heaney's 2004 play The Burial at Thebes makes parallels between Creon with the foreign policies of the Bush administration.[78]

Heaney's engagement with poetry as a necessary engine for cultural and personal change, is reflected in his prose works The Redress of Poetry (1995) and Finders Keepers: Selected Prose, 1971–2001 (2002).[73] "When a poem rhymes," Heaney wrote, "when a form generates itself, when a metre provokes consciousness into new postures, it is already on the side of life. When a rhyme surprises and extends the fixed relations between words, that in itself protests against necessity. When language does more than enough, as it does in all achieved poetry, it opts for the condition of overlife, and rebels at limit." He expands: "The vision of reality which poetry offers should be transformative, more than just a printout of the given circumstances of its time and place".[51] Often overlooked and underestimated in the direction of his work is his profound poetic debts to and critical engagement with 20th-century Eastern European poets, and in particular Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz.[79]

Heaney's work is used extensively on school syllabi internationally, including the anthologies The Rattle Bag (1982) and The School Bag (1997) (both edited with Ted Hughes). Originally entitled The Faber Book of Verse for Younger People on the Faber contract, Hughes and Heaney decided the The Rattle Bag's main purpose was to offer enjoyment to the reader: "Arbitrary riches". Heaney commented "the book in our heads was something closer to The Fancy Free Poetry Supplement".[80] It included work that they would have liked to encountered sooner as well as nonsense rhymes, ballad-type poems, riddles, folk songs and rhythmical jingles. Much familiar canonical work was not included, since they took it for granted that their audience would know the standard fare. Fifteen years later The School Bag aimed at something different. The foreword stated that they wanted "less of a carnival, more like a checklist." It included poems in English, Irish, Welsh, Scots and Scots Gaelic, together with work reflecting the African-American experience.[80] Heaney's work is also the basis for a collaboration with Mohammed Fairouz [81] who composed a choral setting of Heaney's poems.[82]

Publications

Poetry: main collections

- 1966: Death of a Naturalist, Faber & Faber

- 1969: Door into the Dark, Faber & Faber

- 1972: Wintering Out, Faber & Faber

- 1975: North, Faber & Faber

- 1979: Field Work, Faber & Faber

- 1984: Station Island, Faber & Faber

- 1987: The Haw Lantern, Faber & Faber

- 1991: Seeing Things, Faber & Faber

- 1996: The Spirit Level, Faber & Faber

- 2001: Electric Light, Faber & Faber

- 2006: District and Circle, Faber & Faber

- 2010: Human Chain, Faber & Faber

Poetry: collected editions

- 1980: Selected Poems 1965-1975, Faber & Faber

- 1990: New Selected Poems 1966-1987, Faber & Faber

- 1998: Opened Ground: Poems 1966-1996, Faber & Faber

Prose: main collections

- 1980: Preoccupations: Selected Prose 1968–1978, Faber & Faber

- 1988: The Government of the Tongue, Faber & Faber

- 1995: The Redress of Poetry: Oxford Lectures, Faber & Faber

- 2002: Finders Keepers: Selected Prose 1971–2001, Faber & Faber

Plays

- 1990: The Cure at Troy: A version of Sophocles' Philoctetes, Field Day

- 2004: The Burial at Thebes: A version of Sophocles' Antigone, Faber & Faber

Translations

- 1983: Sweeney Astray: A version from the Irish, Field Day

- 1992: Sweeney's Flight (with Rachel Giese, photographer), Faber & Faber

- 1993: The Midnight Verdict: Translations from the Irish of Brian Merriman and from the Metamorphoses of Ovid, Gallery Press

- 1995: Laments, a cycle of Polish Renaissance elegies by Jan Kochanowski, translated with Stanisław Barańczak, Faber & Faber

- 1999: Beowulf, Faber & Faber

- 1999: Diary of One Who Vanished, a song cycle by Leoš Janáček of poems by Ozef Kalda, Faber & Faber

- 2002: Hallaig, Sorley MacLean Trust

- 2002: Arion, a poem by Alexander Pushkin, translated from the Russian, with a note by Olga Carlisle, Arion Press

- 2004: The Testament of Cresseid, Enitharmon Press

- 2004: Columcille The Scribe, The Royal Irish Academy

- 2009: The Testament of Cresseid & Seven Fables, Faber & Faber

- 2013: The Last Walk, Gallery Press

Limited editions and booklets (poetry and prose)

- 1965: Eleven Poems, Queen's University

- 1968: The Island People, BBC

- 1968: Room to Rhyme, Arts Council N.I.

- 1969: A Lough Neagh Sequence, Phoenix

- 1970: Night Drive, Gilbertson

- 1970: A Boy Driving His Father to Confession, Sceptre Press

- 1973: Explorations, BBC

- 1975: Stations, Ulsterman Publications

- 1975: Bog Poems, Rainbow Press

- 1975: The Fire i' the Flint, Oxford University Press

- 1976: Four Poems, Crannog Press

- 1977: Glanmore Sonnets, Editions Monika Beck

- 1977: In Their Element, Arts Council N.I.

- 1978: Robert Lowell: A Memorial Address and an Elegy, Faber & Faber

- 1978: The Makings of a Music, University of Liverpool

- 1978: After Summer, Gallery Press

- 1979: Hedge School, Janus Press

- 1979: Ugolino, Carpenter Press

- 1979: Gravities, Charlotte Press

- 1979: A Family Album, Byron Press

- 1980: Toome, National College of Art and Design

- 1981: Sweeney Praises the Trees, Henry Pearson

- 1982: A Personal Selection, Ulster Museum

- 1982: Poems and a Memoir, Limited Editions Club

- 1983: An Open Letter, Field Day

- 1983: Among Schoolchildren, Queen's University

- 1984: Verses for a Fordham Commencement, Nadja Press

- 1984: Hailstones, Gallery Press

- 1985: From the Republic of Conscience, Amnesty International

- 1985: Place and Displacement, Dove Cottage

- 1985: Towards a Collaboration, Arts Council N.I.

- 1986: Clearances, Cornamona Press

- 1988: Readings in Contemporary Poetry, DIA Art Foundation

- 1988: The Sounds of Rain, Emory University

- 1989: An Upstairs Outlook, Linen Hall Library

- 1989: The Place of Writing, Emory University

- 1990: The Tree Clock, Linen Hall Library

- 1991: Squarings, Hieroglyph Editions

- 1992: Dylan the Durable, Bennington College

- 1992: The Gravel Walks, Lenoir Rhyne College

- 1992: The Golden Bough, Bonnefant Press

- 1993: Keeping Going, Bow and Arrow Press

- 1993: Joy or Night, University of Swansea

- 1994: Extending the Alphabet, Memorial University of Newfoundland

- 1994: Speranza in Reading, University of Tasmania

- 1995: Oscar Wilde Dedication, Westminster Abbey

- 1995: Charles Montgomery Monteith, All Souls College

- 1995: Crediting Poetry: The Nobel Lecture, Gallery Press

- 1997: Poet to Blacksmith, Pim Witteveen

- 1998: Commencement Address, UNC Chapel Hill

- 1998: Audenesque, Maeght

- 1999: The Light of the Leaves, Bonnefant Press

- 2001: Something to Write Home About, Flying Fox

- 2002: Hope and History, Rhodes University

- 2002: Ecologues in Extremis, Royal Irish Academy

- 2002: A Keen for the Coins, Lenoir Rhyne College

- 2003: Squarings, Arion Press

- 2003: Singing School / Poems 1966 – 2002, Rudomino, Moscow

- 2004: Anything can Happen, Town House Publishers

- 2005: The Door Stands Open, Irish Writers Centre

- 2005: A Shiver, Clutag Press

- 2007: The Riverbank Field, Gallery Press

- 2008: Articulations, Royal Irish Academy

- 2008: One on a Side, Robert Frost Foundation

- 2009: Spelling It Out, Gallery Press

- 2010: Writer & Righter, Irish Human Rights Commission

- 2012: Stone From Delphi, Arion Press

Critical studies of Heaney

- 1993: The Poetry of Seamus Heaney ed. by Elmer Andrews, ISBN 0-231-11926-7

- 1993: Seamus Heaney: The Making of the Poet by Michael Parker, ISBN 0-333-47181-4

- 1995: Critical essays on Seamus Heaney ed. by Robert F. Garratt, ISBN 0-7838-0004-5

- 1998: The Poetry of Seamus Heaney: A Critical Study by Neil Corcoran, ISBN 0-571-17747-6

- 2000: Seamus Heaney by Helen Vendler, ISBN 0-674-00205-9, Harvard University Press

- 2000: The Poetry of Seamus Heaney, Ed. Elmer Kennedy-Andrews. Icon Books Ltd., Cambridge CB2 4QF UK ISBN 1-84046-137-3

- 2003: Seamus Heaney and the Place of Writing by Eugene O'Brien, University Press of Florida, ISBN 0-8130-2582-6

- 2004: Seamus Heaney Searches for Answers by Eugene O'Brien, Pluto Press: London, ISBN 0-7453-1734-0

- 2007: Seamus Heaney and the Emblems of Hope by Karen Marguerite Moloney, ISBN 978-0-8262-1744-8

- 2007: Seamus Heaney: Creating Irelands of the Mind by Eugene O'Brien, Liffey Press, Dublin, ISBN 1-904148-02-6

- 2009: The Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney edited by Bernard O'Donoghue, ISBN 0-5215-4755-5

- 2010: Poetry and Peace: Michael Longley, Seamus Heaney, and Northern Ireland by Richard Rankin Russell ISBN 978-0-268-04031-4

- 2010: Defending Poetry: Art and Ethics in Joseph Brodsky, Seamus Heaney, and Geoffrey Hill by David-Antoine Williams

- 2010: “Working Nation(s): Seamus Heaney’s ‘Digging’ and the Work Ethic in Post-Colonial and Minority Writing”, by Ivan Cañadas[83]

- 2011: "Seamus Heaney and Beowulf," by M.J. Toswell, in: Cahier Calin: Makers of the Middle Ages. Essays in Honor of William Calin, ed. Richard Utz and Elizabeth Emery (Kalamazoo, MI: Studies in Medievalism, 2011), pp. 18–22.

- 2012: In Gratitude for all the Gifts: Seamus Heaney and Eastern Europe, by Magdalena Kay. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442644984

- 2012: Raccontarsi in versi. La poesia autobiografica in Inghilterra e in Spagna (1950–1980)., by Menotti Lerro, Carocci.

Selected discography

- 2003 The Poet & The Piper – Seamus Heaney & Liam O'Flynn

- 2009 Collected Poems – Recording of Heaney reading all of his collected poems

Major prizes and honours

- 1966 Eric Gregory Award

- 1967 Cholmondeley Award

- 1968 Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize

- 1975 E. M. Forster Award

- 1975 Duff Cooper Memorial Prize

- 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature

- 1996 Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- 1997 Elected Saoi of Aosdana

- 2001 Golden Wreath of Poetry, the main international award given by Struga Poetry Evenings to a world renowned living poet for life achievement in the field of poetry

- 2005 Irish PEN Award

- 2006 T. S. Eliot Prize for District and Circle

- 2007 Poetry Now Award for District and Circle

- 2009 David Cohen Prize

- 2011 Poetry Now Award for Human Chain

- 2011 Griffin Poetry Prize finalist for Human Chain

- 2011 Bob Hughes Lifetime Achievement Award

- 2012 Griffin Poetry Prize Lifetime Recognition Award[84]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Obituary: Heaney ‘the most important Irish poet since Yeats’ Irish Times, 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d Seamus Heaney obituary The Guardian, 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d McCrum, Robert (19 July 2009). "A life of rhyme". Mail & Guardian. M&G Media Ltd. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ a b "Biography of Irish Writer Seamus Heaney". www.seamusheaney.org. Retrieved 20 February 2010.

Heaney was born on 13th April 1939, the eldest of nine children at the family farm called Mossbawn in the Townland of Tamniarn in Newbridge near Castledawson, Northern Ireland, ...

Archived at Wayback Engine. - ^ Heaney, Seamus (1998). Opened Ground. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-52678-8.

- ^ a b c d "Faces of the week". BBC News. BBC. 19 January 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ a b Sutherland, John (19 March 2009). "Seamus Heaney deserves a lot more than £40,000". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ Pinsky, Robert Poetry and The World The Eco Press Hopewell ISBN 088001217x

- ^ Craig, Patricia (30 August 2013). "Seamus Heaney obituary: Nobel Prize-winning Irish Poet". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Parker, Michael (1993). Seamus Heaney: The Making of the Poet. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 221. ISBN 0-87745-398-5.

The deaths of his mother in the autumn of 1984 and of his father in October 1986 left a colossal space, one which he has struggled to fill through poetry.

- ^ "A Note on Seamus Heaney". inform.orbitaltec.ne. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

Seamus Heaney was born on 13 April 1939, the first child of Patrick and Margaret Kathleen (née McCann) Heaney, who then lived on a fifty-acre farm called Mossbawn, in the townland of Tamniarn, County Derry, Northern Ireland.

- ^ "Biography". Nobelprize. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Verdonk, Peter (2002). Stylistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-19-437240-5.

- ^ Parker, Michael (1993). Seamus Heaney: The Making of the Poet. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-87745-398-5.

Mrs Heaney bore nine children, Seamus, Sheena, Ann, Hugh, Patrick, Charles, Colum, Christopher, and Dan.

- ^ "Heaney, Seamus: Mid-Term Break". Litmed.med.nyu.edu. 27 October 1999. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ "Biography". British Council. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ a b Ed. Bernard O’Donoghue The Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney (2009) Cambridge University Press pxiii ISBN 978-0-521-54755-0. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ Sophia Hillan, New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Autumn, 2005), pp. 86–106 Wintered into Wisdom: Michael McLaverty, Seamus Heaney, and the Northern Word-Hoard. University of St. Thomas (Center for Irish Studies)

- ^ McLaverty, Michael (2002) Collected short stories Blackstaff Press Ltd pxiii ISBN 0-85640-727-5

- ^ "Biography". Aosdána.

- ^ "Irish Nobel Prize Poet Seamus Heaney Dies Aged 74 -VIDEO". Ibtimes.co.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney, "Heaney in Public" by Dennis O'Driscoll (p56-72). ISBN 0-5215-4755-5.

- ^ "Barclay Agency profile". Barclayagency.com. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ British Council biography of Heaney. Retrieved 19 April 2010.

- ^ "Heaney 'catches the heart off guard'". Harvard News Office. Harvard University. 2 October 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

Over the years, readings by poet Seamus Heaney have been so wildly popular that his fans are called "Heaneyboppers."

- ^ "Royal Society of Literature All Fellows". Royal Society of Literature. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ "Play Listing". Irish Playography. Irish Theatre Institute. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1995". Nobelprize. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Clarity, James F. (9 October 1995). "Laureate and Symbol, Heaney Returns Home". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 9 October 1995.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Beowulf: A New Translation". Rambles.net. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ "Seamus Heaney MRIA 1939-2013 - A Very Special Academician". ria.ie. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Seamus Heaney". aosdána.artscouncil.ie. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ University of Pennsylvania. Honorary Degree awarded. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- ^ Rhodes Department of English Annual Report 2002-2003 from the Rhodes University website. Archived at Wayback Engine.

- ^ The Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry from the Queen's University Belfast website

- ^ "Emory Acquires Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney Letters". press release. Emory University. 24 September 2003.

"When I was here this summer for commencement, I came to the decision that the conclusion of President Chace's tenure was the moment of truth, and that I should now lodge a substantial portion of my literary archive in the Woodruff Library, including the correspondence from many of the poets already represented in its special collections," said Heaney in making the announcement. "So I am pleased to say these letters are now here and that even though President Chace is departing, as long as my papers stay here, they will be a memorial to the work he has done to extend the university's resources and strengthen its purpose."

- ^ "Poet Heaney donates papers to Emory". The Augusta Chronicle. Morris Communications. 25 September 2003. Retrieved 25 September 2003.

- ^ Emory University. Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Book Library (MARBL). Online collection of The Belfast Group archive.

- ^ Eminem, The Way I Am, autobiography, cover sheet. Published 21 October 2008.

- ^ "Seamus Heaney praises Eminem". BBC News. BBC. 30 June 2003. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ a b Heaney bid farewell at funeral Belfast Telegraph, 2013-09-02.

- ^ Today Programme, BBC Radio 4, 16 January 2007.

- ^ "Poet 'cried for father' after stroke". BBC News. BBC. 20 July 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ Kelly, Antoinette (19 July 2009). "Nobel winner Seamus Heaney recalls secret visit from Bill Clinton: President visit to Heaney's hospital bed after near-fatal stroke". Irish Central. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ "Heaney wins TS Eliot poetry prize". BBC News. BBC. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2007.

- ^ "Announcement of Awards". University College Dublin. UCD.

- ^ "Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney". The Times. News Corporation. 14 November 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ "Féile an Phobail, Festival of the People, 2010 programme". Official website. Retrieved 12 July 2010. Archived at Wayback Engine.

- ^ a b Page, Benedicte (6 October 2010). "Seamus Heaney wins £10k Forward poetry prize for Human Chain". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Kellaway, Kate (22 August 2010). "Human Chain by Seamus Heaney". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ a b c Tóibín, Colm (21 August 2010). "Human Chain by Seamus Heaney – review". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ^ Naughton, John (8 May 2011). "Britain's top 300 intellectuals". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ^ "Songs of the Scribe Sung by Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin". Journal of Music. 6 December 2011.

- ^ Telford, Lyndsey (21 December 2011). "Seamus Heaney declutters home and donates personal notes to National Library". Irish Independent. Independent News & Media. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Madden, Anne (22 December 2011). "Seamus Heaney's papers go to Dublin, but we don't mind, insists QUB". The Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Prize, Griffin Poetry (7 June 2012). "2012 – Seamus Heaney". Griffin Poetry Prize. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ a b HEANEY, Seamus : Death notice Irish Times, 2013-09-30.

- ^ McGreevy, Ronan (30 August 2013). "Tributes paid to 'keeper of language' Seamus Heaney". The Irish Times. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b Higgins to lead mourners at funeral Mass for poet Sunday Indeppendent, 2013-09-01.

- ^ Seamus Heaney laid to rest in Bellaghy Irish Times, 2013-069-02.

- ^ Seamus Heaney's last words were 'Noli timere', son tells funeral The Guardian, 2013-09-02.

- ^ Epic tale goes Dublin's way Irish Times, 2013-09-02.

- ^ Funeral of Seamus Heaney to be broadcast live on RTÉ TheJournal.ie, 2013-09-01.

- ^ Heaney books sell out amid massive demand Irish Times, 2019-09-05.

- ^ Statement from Áras an Uachtaráin – Seamus Heaney Áras an Uachtaráin, 2013-08-30.

- ^ President Michael D Higgins pays tribute to his friend Seamus Heaney RTÉ News on Youtube, 2013-09-31.

- ^ a b c Tributes to Seamus Heaney BBC News Northern Ireland, 2013-08-30.

- ^ a b "Poet Seamus Heaney dies aged 74". BBC News. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "President and Taoiseach lead tributes to the late Seamus Heaney: Tributes paid to the Nobel Laureate who died this morning at the age of 74". Irish Independent. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b c Higgins, Charlotte; McDonald, Henry (30 August 2013). "Seamus Heaney's death 'leaves breach in language itself': Tributes flow in from fellow writers after poet who won Nobel prize for literature dies in Dublin aged 74". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Tóibín, Colm (30 August 2013). "Seamus Heaney's books were events in our lives". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Heaney deserves place among the pantheon, says Dorgan". The Irish Times. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Biography". Poetry Foundation.

- ^ O'Connell, Shaun (1 February 1985). "Station Island, Seamus Heaney". Boston Review. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ "Terry Eagleton reviews 'Beowulf' translated by Seamus Heaney · LRB 11 November 1999". Lrb.co.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ a b Potts, Robert (7 April 2001). "The view from Olympia". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 7 April 2001.

- ^ a b Rahim, Sameer (11 May 2009). "Interview with Seamus Heaney: On the eve of his 70th birthday, Seamus Heaney tells Sameer Rahim about his lifetime in poetry – and who he thinks would make a good poet laureate". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ McElroy, Steven (21 January 2007). "The Week Ahead: Jan. 21 – 27". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 21 January 2007.

- ^ Kay, Magdalena. In Gratitude for all the Gifts: Seamus Heaney and Eastern Europe. University of Toronto Press, 2012. ISBN 1442644982

- ^ a b Heaney, Seamus (25 October 2003). "Bags of enlightenment". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 25 October 2003.

- ^ Mohammed Fairouz. "BBC World New Collaboration Culture Page". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Grinnell College News". Grinnell.edu. 14 April 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ Cañadas, Ivan (2010). "Working Nation(s): Seamus Heaney's "Digging" and the Work Ethic in Post-Colonial and Minority Writing". EESE: Erfurt Electronic Studies in English.

- ^ Newington, Giles (16 June 2012). "Heaney wins top Canadian prize". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

External links

- Heaney's Nobel acceptance speech

- Template:Worldcat id

- Seamus Heaney at IMDb

- Seamus Heaney at the Poetry Foundation

- Seamus Heaney at the Poetry Archive

- Seamus Heaney at the Academy for American Poets

- Portraits of Heaney at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- BBC Your Paintings in partnership PCF. Painting by Peter Edwards

- Seamus Heaney collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Henri Cole (Fall 1997). "Seamus Heaney, The Art of Poetry No. 75". The Paris Review..

- Lannan Foundation reading and conversation with Dennis O'Driscoll, 1 October 2003. (Audio / video (40 mins). Prose transcript.

- Seamus Heaney: Man of Words and Grace November-December 2013.

- "History and the homeland" video from The New Yorker. 15 October 2008 Paul Muldoon, interviews Heaney. (1 hr).

- Use dmy dates from October 2012

- 1939 births

- 2013 deaths

- Alumni of Queen's University Belfast

- Aosdána members

- Cholmondeley Award winners

- David Cohen Prize recipients

- Dramatists and playwrights from Northern Ireland

- Essayists from Northern Ireland

- Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature

- Fellows of St John's College, Oxford

- Formalist poets

- Golden Wreath laureates

- Harvard University faculty

- Irish Nobel laureates

- Irish poets

- Irish translators

- Nobel laureates from Northern Ireland

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- People educated at St Columb's College

- People from County Londonderry

- People of the Year Awards winners

- Poets from Northern Ireland

- Translators from Irish

- Translators from Old English

- Translators from Polish

- Translators from Scottish Gaelic

- Translators to English

- 20th-century dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century Irish writers

- 20th-century poets

- 21st-century dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century Irish writers

- 21st-century poets

- Members of the Royal Irish Academy

- Oxford Professor of Poetry