San Diego

San Diego | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of San Diego | |

Images from top, left to right: San Diego Skyline, Coronado Bridge, museum in Balboa Park, Serra Museum in Presidio Park and the Old Point Loma lighthouse | |

| Nickname: America's Finest City | |

| Motto: Semper Vigilans (Latin for "Ever Vigilant") | |

Location of San Diego within San Diego County | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Established | July 16, 1769 |

| Incorporated | March 27, 1850 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Body | San Diego City Council |

| • Mayor | Kevin Faulconer |

| • City Attorney | Jan Goldsmith |

| • City Council | List |

| Area | |

• City | 372.40 sq mi (964.51 km2) |

| • Land | 325.19 sq mi (842.23 km2) |

| • Water | 47.21 sq mi (122.27 km2) 12.68% |

| Elevation | sea level to 1,593 ft (sea level to 486 m) |

| Population (Census 2010) | |

• City | 1,307,402 |

| • Rank | 1st in San Diego County 2nd in California 8th in the United States |

| • Density | 4,003/sq mi (1,545.4/km2) |

| • Urban | 2,956,746 |

| • Metro | 3,095,313 |

| Demonym | San Diegan |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 92101-92117, 92119-92124, 92126-92140, 92142, 92145, 92147, 92149-92155, 92158-92172, 92174-92177, 92179, 92182, 92184, 92186, 92187, 92190-92199 |

| Area code(s) | 619, 858 |

| FIPS code | 66000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1661377 |

| Website | www.sandiego.gov |

San Diego /ˌsæn diːˈeɪɡoʊ/ is a major city in California, on the coast of the Pacific Ocean in Southern California, approximately 120 miles (190 km) south of Los Angeles and immediately adjacent to the border with Mexico. San Diego is the eighth largest city in the United States and second largest in California and is one of the fastest growing cities in the nation.[2] San Diego is the birthplace of California[3] and is known for its mild year-round climate, natural deep-water harbor, extensive beaches, long association with the U.S. Navy, and recent emergence as a healthcare and biotechnology development center. The population was estimated to be 1,322,553 as of 2012.[4]

Historically home to the Kumeyaay people, San Diego was the first site visited by Europeans on what is now the West Coast of the United States. Upon landing in San Diego Bay in 1542, Juan Cabrillo claimed the entire area for Spain, forming the basis for the settlement of Alta California 200 years later. The Presidio and Mission of San Diego, founded in 1769, formed the first European settlement in what is now California. In 1821, San Diego became part of newly independent Mexico, and in 1850, became part of the United States following the Mexican-American War and the admission of California to the union.

The city is the seat of San Diego County and is the economic center of the region as well as the San Diego–Tijuana metropolitan area. San Diego's main economic engines are military and defense-related activities, tourism, international trade, and manufacturing. The presence of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), with the affiliated UCSD Medical Center, has helped make the area a center of research in biotechnology.

History

Spanish Empire 1769–1821

First Mexican Empire 1821–1823

United Mexican States 1823–1848

United States 1848–present

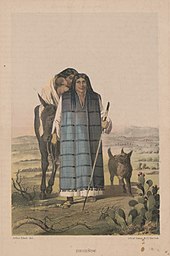

Native American period

The original inhabitants of the region are now known as the San Dieguito and La Jolla people.[5] The area of San Diego has been inhabited by the Kumeyaay people.[6][7] The first European to visit the region was Portuguese-born explorer Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sailing under the flag of Castile. Sailing his flagship San Salvador from Navidad, New Spain, Cabrillo claimed the bay for the Spanish Empire in 1542 and named the site 'San Miguel'.[8] In November 1602, Sebastián Vizcaíno was sent to map the California coast. Arriving on his flagship San Diego, Vizcaíno surveyed the harbor and what are now Mission Bay and Point Loma and named the area for the Catholic Saint Didacus, a Spaniard more commonly known as San Diego de Alcalá. On November 12, 1602, the first Christian religious service of record in Alta California was conducted by Friar Antonio de la Ascensión, a member of Vizcaíno's expedition, to celebrate the feast day of San Diego.[9]

Spanish period

In May 1769, Gaspar de Portolà established the Fort Presidio of San Diego on a hill near the San Diego River. In July of the same year, Mission San Diego de Alcalá was founded by Franciscan friars under Father Junípero Serra.[10] By 1797, the mission boasted the largest native population in Alta California, with over 1,400 neophytes living in and around the mission proper.[11] Mission San Diego was the southern anchor in California of the historic mission trail El Camino Real. Both the Presidio and the Mission are National Historic Landmarks.[12][13]

Mexican period

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain, and San Diego became part of the Mexican state of Alta California. The fort on Presidio Hill was gradually abandoned, while the town of San Diego grew up on the level land below Presidio Hill. The Mission was secularized by the Mexican government in 1834, and most of the Mission lands were sold to wealthy Californio settlers. The 432 residents of the town petitioned the governor to form a pueblo, and Juan María Osuna was elected the first alcalde ("municipal magistrate"), defeating Pío Pico in the vote. (See, List of pre-statehood mayors of San Diego.) However, San Diego had been losing population throughout the 1830s and in 1838 the town lost its pueblo status because its size dropped to an estimated 100 to 150 residents.[14] Beyond town Mexican land grants expanded the number of California ranchos that modestly added to the local economy.

In 1846, the United States went to war against Mexico and sent a naval and land expedition to conquer Alta California. At first they had an easy time of it capturing the major ports including San Diego, but the Californios in southern Alta California struck back. Following the successful revolt in Los Angeles, the American garrison at San Diego was driven out without firing a shot in early October 1846. Mexican partisans held San Diego for three weeks until October 24, 1846, when the Americans recaptured it. For the next several months the Americans were blockaded inside the pueblo. Skirmishes occurred daily and snipers shot into the town every night. The Californios drove cattle away from the pueblo hoping to starve the Americans and their Californio supporters out. On December 1 the Americans garrison learned that the dragoons of General Stephen W. Kearney were at Warner's Ranch. Commodore Robert F. Stockton sent a mounted force of fifty under Captain Archibald Gillespie to march north to meet him. Their joint command of 150 men, returning to San Diego, encountered about 93 Californios under Andrés Pico. In the ensuing Battle of San Pasqual, fought in the San Pasqual Valley which is now part of the city of San Diego, the Americans suffered their worst losses in the campaign. Subsequently a column led by Lieutenant Gray arrived from San Diego, rescuing Kearny's battered and blockaded command.[15]

Stockton and Kearny went on to recover Los Angeles and force the capitulation of Alta California with the "Treaty of Cahuenga" on January 13, 1847. As a result of the Mexican-American War of 1846–1848, the territory of Alta California, including San Diego, was ceded to the United States by Mexico, under the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. The Mexican negotiators of that treaty tried to retain San Diego as part of Mexico, but the Americans insisted that San Diego was "for every commercial purpose of nearly equal importance to us with that of San Francisco," and the Mexican-American border was eventually established to be one league south of the southernmost point of San Diego Bay, so as to include the entire bay within the United States.[16]

American period

The state of California was admitted to the United States in 1850. That same year San Diego was designated the seat of the newly established San Diego County and was incorporated as a city. The initial city charter was established in 1889 and today's city charter was adopted in 1931.[17]

The original town of San Diego was located at the foot of Presidio Hill, in the area which is now Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. The location was not ideal, being several miles away from navigable water. In 1850, William Heath Davis promoted a new development by the Bay shore called "New San Diego", several miles south of the original settlement; however, for several decades the new development consisted only a few houses, a pier and an Army depot. In the late 1860s, Alonzo Horton promoted a move to the bayside area, which he called "New Town" and which became Downtown San Diego. Horton promoted the area heavily, and people and businesses began to relocate to New Town because of its location on San Diego Bay convenient to shipping. New Town soon eclipsed the original settlement, known to this day as Old Town, and became the economic and governmental heart of the city.[18] Still, San Diego remained a relative backwater until the arrival of a railroad connection in 1878.

In the early part of the 20th century, San Diego hosted two World's Fairs: the Panama-California Exposition in 1915 and the California Pacific International Exposition in 1935. Both expositions were held in Balboa Park, and many of the Spanish/Baroque-style buildings that were built for those expositions remain to this day as central features of the park. The buildings were intended to be temporary structures, but most remained in continuous use until they progressively fell into disrepair. Most were eventually rebuilt, using castings of the original facades to retain the architectural style.[19] The menagerie of exotic animals featured at the 1915 exposition provided the basis for the San Diego Zoo.[20]

The southern portion of the Point Loma peninsula was set aside for military purposes as early as 1852. Over the next several decades the Army set up a series of coastal artillery batteries and named the area Fort Rosecrans.[21] Significant U.S. Navy presence began in 1901 with the establishment of the Navy Coaling Station in Point Loma, and expanded greatly during the 1920s.[22] By 1930 the city was host to Naval Base San Diego, Naval Training Center San Diego, San Diego Naval Hospital, Camp Matthews, and Camp Kearny (now Marine Corps Air Station Miramar). The city was also an early center for aviation: as early as World War I San Diego was proclaiming itself "The Air Capital of the West."[23] The city was home to important airplane developers and manufacturers like Ryan Airlines (later Ryan Aeronautical), founded in 1925, and Consolidated Aircraft (later Convair), founded in 1923. Charles A. Lindbergh's plane The Spirit of St. Louis was built in San Diego in 1927 by Ryan Airlines.[23]

During World War II, San Diego became a major hub of military and defense activity, due to the presence of so many military installations and defense manufacturers. The city's population grew rapidly during and after World War II, more than doubling between 1930 (147,995) and 1950 (333,865).[24] After World War II, the military continued to play a major role in the local economy, but post-Cold War cutbacks took a heavy toll on the local defense and aerospace industries. The resulting downturn led San Diego leaders to seek to diversify the city's economy by focusing on research and science, as well as tourism.[25]

From the start of the 20th century through the 1970s, the American tuna fishing fleet and tuna canning industry were based in San Diego, "the tuna capital of the world".[26] San Diego's first tuna cannery was founded in 1911, and by the mid-1930s the canneries employed more than 1,000 people. A large fishing fleet supported the canneries, mostly staffed by immigrant fishermen from Japan, and later from the Portuguese Azores and Italy whose influence is still felt in neighborhoods like Little Italy and Point Loma.[27][28] Due to rising costs and foreign competition, the last of the canneries closed in the early 1980s.[29]

Downtown San Diego was in decline in the 1960s and 1970s but experienced some urban renewal since the early 1980s, including the opening of Horton Plaza, the revival of the Gaslamp Quarter, and the construction of the San Diego Convention Center; Petco Park opened in 2004.[30]

Geography

According to SDSU professor emeritus Monte Marshall, San Diego Bay is "the surface expression of a north-south-trending, nested graben". The Rose Canyon and Point Loma fault zones are part of the San Andreas Fault system. About 15 miles east of the bay are the Laguna Mountains in the Peninsular Ranges, which are part of the backbone of the American continents.[31]

The city lies on approximately 200 deep canyons and hills separating its mesas, creating small pockets of natural open space scattered throughout the city and giving it a hilly geography.[32] Traditionally, San Diegans have built their homes and businesses on the mesas, while leaving the urban canyons relatively wild.[33] Thus, the canyons give parts of the city a segmented feel, creating gaps between otherwise proximate neighborhoods and contributing to a low-density, car-centered environment. The San Diego River runs through the middle of San Diego from east to west, creating a river valley which serves to divide the city into northern and southern segments. The river used to flow into San Diego Bay and its fresh water was the focus of the earliest Spanish explorers.[citation needed] Several reservoirs and Mission Trails Regional Park also lie between and separate developed areas of the city.

Notable peaks within the city limits include Cowles Mountain, the highest point in the city at 1,593 feet (486 m); Black Mountain at 1,558 feet (475 m); and Mount Soledad at 824 feet (251 m). The Cuyamaca Mountains and Laguna Mountains rise to the east of the city, and beyond the mountains are desert areas. The Cleveland National Forest is a half-hour drive from downtown San Diego. Numerous farms are found in the valleys northeast and southeast of the city.

In its 2013 ParkScore ranking, The Trust for Public Land reported that San Diego had the 9th best park system among the 50 most populous U.S. cities.[34] ParkScore ranks city park systems by a formula that analyzes acreage, access, and service and investment.

Communities and neighborhoods

The city of San Diego recognizes 52 individual areas as Community Planning Areas.[35] Within a given planning area there may be several distinct neighborhoods. Altogether the city contains more than 100 identified neighborhoods.

Downtown San Diego is located on San Diego Bay. Balboa Park encompasses several mesas and canyons to the northeast, surrounded by older, dense urban communities including Hillcrest and North Park. To the east and southeast lie City Heights, the College Area, and Southeast San Diego. To the north lies Mission Valley and Interstate 8. The communities north of the valley and freeway, and south of Marine Corps Air Station Miramar, include Clairemont, Kearny Mesa, Tierrasanta, and Navajo. Stretching north from Miramar are the northern suburbs of Mira Mesa, Scripps Ranch, Rancho Peñasquitos, and Rancho Bernardo. The far northeast portion of the city encompasses Lake Hodges and the San Pasqual Valley, which holds an agricultural preserve. Carmel Valley and Del Mar Heights occupy the northwest corner of the city. To their south are Torrey Pines State Reserve and the business center of the Golden Triangle. Further south are the beach and coastal communities of La Jolla, Pacific Beach, and Ocean Beach. Point Loma occupies the peninsula across San Diego Bay from downtown. The communities of South San Diego, such as San Ysidro and Otay Mesa, are located next to the Mexico – United States border, and are physically separated from the rest of the city by the cities of National City and Chula Vista. A narrow strip of land at the bottom of San Diego Bay connects these southern neighborhoods with the rest of the city.

For the most part, San Diego neighborhood boundaries tend to be understood by its residents based on geographical boundaries like canyons and street patterns.[36] The city recognized the importance of its neighborhoods when it organized its 2008 General Plan around the concept of a "City of Villages".[37]

Cityscape

San Diego was originally centered in the Old Town district, but by the late 1860s the center of focus had relocated to the bayfront in the belief that this new location would increase trade. As the "New Town" – present-day Downtown – waterfront location quickly developed, it eclipsed Old Town as the center of San Diego.[38]

The development of skyscrapers over 300 feet (91 m) in San Diego is attributed to the construction of the El Cortez Apartment Hotel in 1927, the tallest building in the city from 1927 to 1963.[39] As time went on multiple buildings claimed the title of San Diego's tallest skyscraper, including the Union Bank of California Building and Symphony Towers. Currently the tallest building in San Diego is One America Plaza, standing 500 feet (150 m) tall, which was completed in 1991.[40] The downtown skyline contains no super-talls, as a regulation put in place by the Federal Aviation Administration in the 1970s set a 500 feet (152 m) limit on the height of buildings due to the proximity of San Diego International Airport.[41] An iconic description of the skyline includes its skyscrapers being compared to the tools of a toolbox.[42]

Climate

San Diego is one of the top-ten best climates in the Farmer’s Almanac[43] and is one of the two best summer climates in America as scored by The Weather Channel.[44] Under the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system, the San Diego area has been variously categorized as having either a semi-arid climate (BSh in the original classification)[45] and (BSkn in modified Köppen classification)[46] or a Mediterranean climate[47] (Csa) and (Csb).[48] San Diego’s climate is characterized by warm, dry summers and mild winters with most of the annual precipitation falling between December and March. The city has a mild climate year-round,[49] with an average of 201 days above 70 °F (21 °C) and low rainfall (9–13 inches [23–33 cm] annually).

The climate in San Diego, like most of Southern California, often varies significantly over short geographical distances resulting in microclimates. In San Diego, this is mostly because of the city’s topography (the Bay, and the numerous hills, mountains, and canyons). Frequently, particularly during the “May gray/June gloom” period, a thick “marine layer” cloud cover will keep the air cool and damp within a few miles of the coast, but will yield to bright cloudless sunshine approximately 5–10 miles (8.0–16.1 km) inland.[50] Sometimes the June gloom can last into July, causing cloudy skies over most of San Diego for the entire day.[51][52] Even in the absence of June gloom, inland areas tend to experience much more significant temperature variations than coastal areas, where the ocean serves as a moderating influence. Thus, for example, downtown San Diego averages January lows of 50 °F (10 °C) and August highs of 78 °F (26 °C). The city of El Cajon, just 10 miles (16 km) inland from downtown San Diego, averages January lows of 42 °F (6 °C) and August highs of 88 °F (31 °C).

A sign of global warming, scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography say the average surface temperature of the water at Scripps Pier in the California Current has increased by almost 3 degrees since 1950.[53]

Rainfall along the coast averages about 10 inches (250 mm) of precipitation annually. The average (mean) rainfall is 10.65 inches (271 mm) and the median is 9.6 inches (240 mm).[54] Most of the rainfall occurs during the cooler months. The months of December through March supply most of the rain, with February the only month averaging 2 inches (51 mm) or more of rain. The months of May through September tend to be almost completely dry. Though there are few wet days per month during the rainy period, rainfall can be heavy when it does fall. Rainfall is usually greater in the higher elevations of San Diego; some of the higher elevation areas of San Diego can receive 11–15 inches (280–380 mm) of rain a year. Variability of rainfall can be extreme: in the wettest years of 1883/1884 and 1940/1941 more than 24 inches (610 mm) fell in the city, whilst in the driest years as little as 3.2 inches (80 mm) has fallen for a full year. The wettest month on record has been December 1921 with 9.21 inches (234 mm).

Snow in the city is so rare that it has been observed only five times in the century-and-a-half that records have been kept. In 1949 and 1967, snow stayed on the ground for a few hours in higher locations like Point Loma and La Jolla. The other three occasions, in 1882, 1946, and 1987, involved flurries but no accumulation.[55]

Official temperature record-keeping began in San Diego in 1872,[56] although other weather records go back further. The city's first official weather station was at Mission San Diego from 1849 to 1858. From August 1858 until 1940, the official weather station was at a series of downtown buildings, and the station has been at Lindbergh Field since February 1940.[57]

| Climate data for San Diego, California (Lindbergh Field (SAN)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

90 (32) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

100 (38) |

98 (37) |

111 (44) |

107 (42) |

97 (36) |

88 (31) |

111 (44) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 65.7 (18.7) |

65.6 (18.7) |

66.2 (19.0) |

68.1 (20.1) |

69.1 (20.6) |

71.3 (21.8) |

75.1 (23.9) |

76.9 (24.9) |

76.4 (24.7) |

73.3 (22.9) |

69.5 (20.8) |

65.3 (18.5) |

70.2 (21.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 57.6 (14.2) |

58.4 (14.7) |

59.9 (15.5) |

62.2 (16.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

70.5 (21.4) |

72.0 (22.2) |

71.0 (21.7) |

67.2 (19.6) |

61.8 (16.6) |

57.1 (13.9) |

64.1 (17.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 49.5 (9.7) |

51.2 (10.7) |

53.7 (12.1) |

56.4 (13.6) |

59.9 (15.5) |

62.5 (16.9) |

65.9 (18.8) |

66.7 (19.3) |

65.6 (18.7) |

61.1 (16.2) |

54.0 (12.2) |

48.9 (9.4) |

58.0 (14.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 29 (−2) |

36 (2) |

39 (4) |

41 (5) |

47 (8) |

50 (10) |

55 (13) |

57 (14) |

51 (11) |

43 (6) |

38 (3) |

34 (1) |

29 (−2) |

| Average rainfall inches (mm) | 1.98 (50) |

2.27 (58) |

1.81 (46) |

0.78 (20) |

0.12 (3.0) |

0.07 (1.8) |

0.03 (0.76) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.15 (3.8) |

0.57 (14) |

1.00 (25) |

1.53 (39) |

10.33 (262) |

| Average rainy days | 6.7 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 4.1 | 5.8 | 41.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 239.3 | 227.4 | 261.0 | 276.2 | 250.5 | 242.4 | 304.7 | 295.0 | 253.3 | 243.4 | 230.1 | 231.3 | 3,054.6 |

| Source 1: Temperature & rainy days data: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NOWData (1981-2010)[58][citation needed] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Mean monthly sunshine hours: San Diego/Lindbergh Field CA Climate Normals (1961–1990)[59] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

Like most of southern California, the majority of San Diego's current area was originally occupied by chaparral, a plant community made up mostly of drought-resistant shrubs. The endangered Torrey Pine has the bulk of its population in San Diego in a stretch of protected chaparral along the coast. The steep and varied topography and proximity to the ocean create a number of different habitats within the city limits, including tidal marsh and canyons. The chaparral and coastal sage scrub habitats in low elevations along the coast are prone to wildfire, and the rates of fire have increased in the 20th century, due primarily to fires starting near the borders of urban and wild areas.[60]

San Diego's broad city limits encompass a number of large nature preserves, including Torrey Pines State Reserve, Los Peñasquitos Canyon Preserve, and Mission Trails Regional Park. Torrey Pines State Reserve and a coastal strip continuing to the north constitute the only location where the rare species of Torrey Pine, P. torreyana torreyana, is found.[61]

Due to the steep topography that prevents or discourages building, along with some efforts for preservation, there are also a large number of canyons within the city limits that serve as nature preserves, including Switzer Canyon, Tecolote Canyon Natural Park,[62] and Marian Bear Memorial Park in the San Clemente Canyon,[63] as well as a number of small parks and preserves.

San Diego County has one of the highest counts of animal and plant species that appear on the endangered species list among counties in the United States.[64] Because of its diversity of habitat and its position on the Pacific Flyway, San Diego County has recorded the presence of 492 bird species, more than any other region in the country.[65] San Diego always scores very high in the number of bird species observed in the annual Christmas Bird Count, sponsored by the Audubon Society, and it is known as one of the "birdiest" areas in the United States.[66][67]

San Diego and its backcountry are subject to periodic wildfires. In October 2003, San Diego was the site of the Cedar Fire, which has been called the largest wildfire in California over the past century.[68] The fire burned 280,000 acres (1,100 km2), killed 15 people, and destroyed more than 2,200 homes.[69] In addition to damage caused by the fire, smoke resulted in a significant increase in emergency room visits due to asthma, respiratory problems, eye irritation, and smoke inhalation; the poor air quality caused San Diego County schools to close for a week.[70] Wildfires four years later destroyed some areas, particularly within the communities of Rancho Bernardo, Rancho Santa Fe, and Ramona.[71]

Demographics

The city had a population of 1,307,402 according to the 2010 census, distributed over a land area of 372.1 square miles (963.7 km2). The urban area of San Diego extends beyond the administrative city limits and had a total population of 2,956,746, making it the third-largest urban area in the state, after that of the Los Angeles metropolitan area and San Francisco metropolitan area. They, along with the Riverside–San Bernardino, form those metropolitan areas in California larger than the San Diego metropolitan area, with a total population of 3,095,313 at the 2010 census.

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 500 | — | |

| 1860 | 731 | 46.2% | |

| 1870 | 2,300 | 214.6% | |

| 1880 | 2,637 | 14.7% | |

| 1890 | 16,159 | 512.8% | |

| 1900 | 17,700 | 9.5% | |

| 1910 | 39,578 | 123.6% | |

| 1920 | 74,361 | 87.9% | |

| 1930 | 147,995 | 99.0% | |

| 1940 | 203,341 | 37.4% | |

| 1950 | 333,865 | 64.2% | |

| 1960 | 573,224 | 71.7% | |

| 1970 | 696,769 | 21.6% | |

| 1980 | 875,538 | 25.7% | |

| 1990 | 1,110,549 | 26.8% | |

| 2000 | 1,223,400 | 10.2% | |

| 2010 | 1,307,402 | 6.9% | |

| 2012 (est.) | 1,338,348 | [72] | 2.4% |

| source:[24][73] | |||

As of the Census of 2010, there were 1,307,402 people living in the city of San Diego.[74] That represents a population increase of just under 7% from the 1,223,400 people, 450,691 households, and 271,315 families reported in 2000.[75] The estimated city population in 2009 was 1,306,300. The population density was 3,771.9 people per square mile (1,456.4/km2). The racial makeup of San Diego was 45.1% White, 6.7% African American, 0.6% Native American, 15.9% Asian (5.9% Filipino, 2.7% Chinese, 2.5% Vietnamese, 1.3% Indian, 1.0% Korean, 0.7% Japanese, 0.4% Laotian, 0.3% Cambodian, 0.1% Thai). 0.5% Pacific Islander (0.2% Guamanian, 0.1% Samoan, 0.1% Native Hawaiian), 12.3% from other races, and 5.1% from two or more races. The ethnic makeup of the city was 28.8% Hispanic or Latino (of any race), putting the non-Hispanic or Latino population (of any race) at 71.2%.[76][77] 24.9% of the total population were Mexican American, and 0.6% were Puerto Rican.

As of December 2012[update], San Diego has the third largest homeless population in the United States;[78] the city's homeless population has the largest percentage of homeless veterans in the nation.[78]

As of January 1, 2008 estimates by the San Diego Association of Governments revealed that the household median income for San Diego rose to $66,715, up from $45,733, and that the city population rose to 1,336,865, up 9.3% from 2000.[79] The population was 45.3% non-Hispanic whites, down from 78.9% in 1970,[80] 27.7% Hispanics, 15.6% Asians/Pacific Islanders, 7.1% blacks, 0.4% American Indians, and 3.9% from other races. Median age of Hispanics was 27.5 years, compared to 35.1 years overall and 41.6 years among non-Hispanic whites; Hispanics were the largest group in all ages under 18, and non-Hispanic whites constituted 63.1% of population 55 and older.

In 2000 there were 451,126 households out of which 30.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.6% were married couples living together, 11.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.8% were non-families. Households made up of individuals account for 28.0% and 7.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.61 and the average family size was 3.30.

The U.S. Census Bureau reported that in 2000, 24.0% of San Diego residents were under 18, and 10.5% were 65 and over.[81] The median age was 32; two-thirds of the population was under 35.[82] The San Diego County regional planning agency, SANDAG, provides tables and graphs breaking down the city population into 5-year age groups.[83] In 2000, the median income for a household in the city was $45,733, and the median income for a family was $53,060.[84] Males had a median income of $36,984 versus $31,076 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,609.[84] According to Forbes in 2005, San Diego was the fifth wealthiest U.S. city[85] but about 10.6% of families and 14.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.0% of those under age 18 and 7.6% of those age 65 or over.[84] Nonetheless, San Diego was rated the fifth-best place to live in the United States in 2006 by Money magazine.[86]

Economy

The largest sectors of San Diego's economy are defense/military, tourism, international trade, and research/manufacturing, respectively.[87][88]

Defense and military

The economy of San Diego is influenced by its deepwater port, which includes the only major submarine and shipbuilding yards on the West Coast.[89] Several major national defense contractors were started and are headquartered in San Diego, including General Atomics, Cubic, and NASSCO.[90][91]

San Diego hosts the largest naval fleet in the world:[92] it was in 2008 was home to 53 ships, over 120 tenant commands, and more than 35,000 sailors, soldiers, Department of Defense civilian employees and contractors.[93] About 5 percent of all civilian jobs in the county are military-related, and 15,000 businesses in San Diego County rely on Department of Defense contracts.[93]

Military bases in San Diego include US Navy facilities, Marine Corps bases, and Coast Guard stations. Marine Corps institutions in the city of San Diego include Marine Corps Air Station Miramar and Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego. The Navy has several institutions in the city, including Naval Base Point Loma, Naval Base San Diego (also known as the 32nd Street Naval Station), Naval Medical Center San Diego (also known as Bob Wilson Naval Hospital), the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center San Diego, and Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command ("SPAWAR"). Also near San Diego but not within the city limits are Naval Amphibious Base Coronado and Naval Air Station North Island (which operates Naval Auxiliary Landing Facility San Clemente Island, Silver Strand Training Complex, and the Outlying Field Imperial Beach). San Diego is known as the "birthplace of naval aviation".[94]

The city is "home to the majority of the U.S. Pacific Fleet's surface combatants, all of the Navy's West Coast amphibious ships and a variety of Coast Guard and Military Sealift Command vessels".[93][95] Two Nimitz class supercarriers, (the USS Carl Vinson, and USS Ronald Reagan),[96][97][98] five amphibious assault ships, several Los Angeles-class "fast attack" submarines, the Hospital Ship USNS Mercy,[99][100] carrier and submarine tenders, destroyers, cruisers, frigates, and many smaller ships are home-ported there.[97] Four Navy vessels have been named USS San Diego.[101]

Tourism

Tourism is a major industry owing to the city's climate, its beaches, and numerous tourist attractions such as Balboa Park, Belmont amusement park, San Diego Zoo, San Diego Zoo Safari Park, and SeaWorld San Diego. San Diego's Spanish and Mexican heritage is reflected in the many historic sites across the city, such as Mission San Diego de Alcala and Old Town San Diego State Historic Park. Annual events in San Diego include Comic-Con, the Farmers Insurance Open golf tournament, San Diego Pride, the San Diego Black Film Festival, and Street Scene Music Festival. Also, the local craft brewing industry attracts an increasing number of visitors[102] for "beer tours" and the annual San Diego Beer Week in November;[103] San Diego has been called "America's Craft Beer Capital."[104]

San Diego County hosted more than 32 million visitors in 2012, of whom approximately half stayed overnight and half were day visitors; collectively they spent an estimated $8 billion locally, with a regional economic impact of more than $18 billion. The visitor industry provides employment for more than 160,000 people.[105] The San Diego Convention Center hosted 68 out-of-town conventions and trade shows in 2009, attracting more than 600,000 visitors.[105] Transient Occupancy Taxes (TOT) have created funding for the City of San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture.[106]

San Diego's cruise ship industry used to be the second largest in California. Each cruise ship call injects an estimated $2 million (from the purchase of food, fuel, supplies, and maintenance services, not counting the money spent by the tourists) into the local economy.[107] Numerous cruise lines, including Carnival, Holland America, Celebrity, Crystal and Princess, operate out of San Diego. However, cruise ship business has been in steady decline since peaking in 2008, when the Port hosted over 250 ship calls and more than 900,000 passengers. By 2011 the number of ship calls had fallen to 103 (estimated).[108] Holland America and Carnival Cruises operated weekly cruises to the Mexican Riviera for many years, but both ended their regular scheduled service in spring 2012, which was an economic loss to the region of more than $100 million.[108] The decline is blamed on the slumping economy as well as fear of travel to Mexico due to well-publicized violence there.[109]

There are local cruises in San Diego Bay and Mission Bay, available through companies such as Hornblower and H&M. These include sightseeing and "sunset" cruises as well as private-event or "party" cruises. Also available are whale watching cruises to observe the migration of tens of thousands of gray whales that pass by San Diego, peaking in mid-January,[110] and year-round sport fishing expeditions.

International trade

San Diego's commercial port and its location on the United States-Mexico border make international trade an important factor in the city's economy. The city is authorized by the United States government to operate as a Foreign Trade Zone.[111]

The city shares a 15-mile (24 km) border with Mexico that includes two border crossings. San Diego hosts the busiest international border crossing in the world, in the San Ysidro neighborhood at the San Ysidro Port of Entry.[112] A second, primarily commercial border crossing operates in the Otay Mesa area; it is the largest commercial crossing on the California-Baja California border and handles the third highest volume of trucks and dollar value of trade among all United States-Mexico land crossings.[113]

One of the Port of San Diego's two cargo facilities is located in Downtown San Diego at the Tenth Avenue Marine Terminal. This terminal has facilities for containers, bulk cargo, and refrigerated and frozen storage, so that it can handle the import and export of perishables (including 33 million bananas every month) as well as fertilizer, cement, forest products, and other commodities.[114] In 2009 the Port of San Diego handled 1,137,054 short tons of total trade; foreign trade accounted for 956,637 short tons while domestic trade amounted to 180,417 short tons.[115]

Manufacturing and research

In 2010, former Governor Schwarzenegger’s Office of Economic Development designated San Diego as an iHub Innovation Center for collaboration potentially between wireless and life sciences, citing the area's wireless business, pharmaceutical research and start-ups for medical devices and diagnostics.[116]

San Diego hosts several major producers of wireless cellular technology. Qualcomm was founded and is headquartered in San Diego, and still is the largest private-sector technology employer (excluding hospitals) in San Diego County.[117] Other wireless industry manufacturers headquartered here include Nokia, LG Electronics,[118] Kyocera International.,[119] Cricket Communications and Novatel Wireless.[120] According to the San Diego Business Journal, the largest software company in San Diego is security software company Websense Inc.[121] San Diego also has the U.S. headquarters for the Slovakian security company ESET.[122]

The presence of the University of California, San Diego and other research institutions has helped to fuel biotechnology growth.[123] In June 2004, San Diego was ranked the top biotech cluster in the United States by the Milken Institute.[124] In 2013, San Diego has the second largest biotech cluster in the United States, below the Boston area and above the San Francisco Bay Area.[125] There are more than 400 biotechnology companies in the area.[126] In particular, the La Jolla and nearby Sorrento Valley areas are home to offices and research facilities for numerous biotechnology companies.[127] Major biotechnology companies like Neurocrine Biosciences and Nventa Biopharmaceuticals are headquartered in San Diego, while many biotech and pharmaceutical companies, such as BD Biosciences, Biogen Idec, Integrated DNA Technologies, Merck, Pfizer, Élan, Celgene, and Vertex, have offices or research facilities in San Diego. There are also several non-profit biotech and health care institutes, such as the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, the Scripps Research Institute, the West Wireless Health Institute and the Sanford-Burnham Institute. San Diego is also home to more than 140 contract research organizations (CROs) that provide a variety of contract services for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.[128]

Historically tuna fishing and canning was one of San Diego's major industries,[129] and although the American tuna fishing fleet is no longer based in San Diego, seafood companies Bumble Bee Foods and Chicken of the Sea are still headquartered there.[130][131]

Real estate

Prior to 2006, San Diego experienced a dramatic growth of real estate prices, to the extent that the situation was sometimes described as a "housing affordability crisis". Median single family home prices more than tripled between 1998 and 2007. According to the California Association of Realtors, in May 2007 a median house in San Diego cost $612,370.[132] Growth of real estate prices was not accompanied by comparable growth of household incomes: the Housing Affordability Index (percentage of households that can afford to buy a median-priced house) fell below 20 percent in the early 2000s. The San Diego metropolitan area had one of the worst median multiples (ratio of median house price to median household income) of all metropolitan areas in the United States,[133] a situation sometimes referred to as a Sunshine tax. As a consequence, San Diego experienced negative net migration since 2004. A significant number of people moved to adjacent Riverside County, commuting daily from Temecula and Murrieta to jobs in San Diego. Many of San Diego's home buyers tend to buy homes within the more affordable neighborhoods, while others are leaving the state altogether and moving to more affordable regions of the country.[134]

San Diego home prices peaked in 2005, then declined as part of a nationwide trend. As of December 2010, home prices were 60 percent higher than in 2000, but down 36 percent from the peak in 2005.[135] The median home price declined by more than $200,000 between 2005 and 2010, and sales dropped by 50 percent.[136]

Top employers

According to the City's 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[137] the top employers in the city are:

| Employer | Number of employees |

|---|---|

| United States Navy | 30,664 |

| University of California, San Diego | 28,071 |

| Sharp HealthCare | 15,906 |

| San Diego County | 15,727 |

| San Diego Unified School District | 13,552 |

| Qualcomm | 13,524 |

| City of San Diego | 10,026 |

| Kaiser Permanente | 8,800 |

| UC San Diego Health System | 6,235 |

| San Diego Gas & Electric | 4,753 |

Culture

Many popular museums, such as the San Diego Museum of Art, the San Diego Natural History Museum, the San Diego Museum of Man, the Museum of Photographic Arts, and the San Diego Air & Space Museum are located in Balboa Park. The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD) is located in La Jolla and has a branch located at the Santa Fe Depot downtown. The downtown one consists of two building on two opposite streets. The Columbia district downtown is home to historic ship exhibits belonging to the San Diego Maritime Museum, headlined by the Star of India, as well as the unrelated San Diego Aircraft Carrier Museum featuring the USS Midway aircraft carrier.

The San Diego Symphony at Symphony Towers performs on a regular basis and is directed by Jahja Ling. The San Diego Opera at Civic Center Plaza, directed by Ian Campbell, was ranked by Opera America as one of the top 10 opera companies in the United States. Old Globe Theatre at Balboa Park produces about 15 plays and musicals annually. The La Jolla Playhouse at UCSD is directed by Christopher Ashley. Both the Old Globe Theatre and the La Jolla Playhouse have produced the world premieres of plays and musicals that have gone on to win Tony Awards[138] or nominations[139] on Broadway. The Joan B. Kroc Theatre at Kroc Center's Performing Arts Center is a 600-seat state-of-the-art theatre that hosts music, dance, and theatre performances. The San Diego Repertory Theatre at the Lyceum Theatres in Horton Plaza produces a variety of plays and musicals. Hundreds of movies and a dozen TV shows have been filmed in San Diego, a tradition going back as far as 1898.[140]

Sports

The National Football League's San Diego Chargers play in Qualcomm Stadium. Three NFL Super Bowl championships have been held there. Major League Baseball's San Diego Padres play in Petco Park. Parts of the World Baseball Classic were played there in 2006 and 2009.

NCAA Division I San Diego State Aztecs men's and women's basketball games are played at Viejas Arena at Aztec Bowl on the campus of San Diego State University. College football and soccer, basketball and volleyball are played at the Torero Stadium and the Jenny Craig Pavilion at USD.

The San Diego State Aztecs (MWC) and the University of San Diego Toreros (WCC) are NCAA Division I teams. The UCSD Tritons (CCAA) are members of NCAA Division II while the Point Loma Nazarene Sea Lions and San Diego Christian College (GSAC) are members of the NAIA.

Qualcomm Stadium also houses the NCAA Division I San Diego State Aztecs, as well as local high school football championships, international soccer games, and supercross events. Two of college football's annual bowl games are also held there: the Holiday Bowl and the Poinsettia Bowl. Soccer, American football, and track and field are also played in Balboa Stadium, the city's first stadium, constructed in 1914.

Rugby union is a developing sport in the city. The USA Sevens, a major rugby event, was held there from 2007 through 2009. San Diego is one of only 16 cities in the United States included in the Rugby Super League[141] represented by Old Mission Beach Athletic Club RFC, the home club of USA Rugby's Captain Todd Clever who plays rugby professionally in Japan's Top League with Suntory Sungoliath.[142] San Diego will participate in the Western American National Rugby League which starts in 2011.[143]

The San Diego Surf of the American Basketball Association is located in the city. The annual Farmers Insurance Open golf tournament (formerly the Buick Invitational) on the PGA Tour occurs at the municipally owned Torrey Pines Golf Course. This course was also the site of the 2008 U.S. Open Golf Championship. The San Diego Yacht Club hosted the America's Cup yacht races three times during the period 1988 to 1995. The amateur beach sport Over-the-line was invented in San Diego,[144] and the annual world Over-the-line championships are held at Mission Bay every year.[145]

Government

Local government

The city is governed by a mayor and a 9-member city council. In 2006, the city's form of government changed from a council–manager government to a strong mayor government. The change was brought about by a citywide vote in 2004. The mayor is in effect the chief executive officer of the city, while the council is the legislative body.[146] The City of San Diego is responsible for police, public safety, streets, water and sewer service, planning and zoning, and similar services within its borders. San Diego is a sanctuary city,[147] however, San Diego County is a participant of the Secure Communities program.[148][149]

The members of the city council are each elected from single member districts within the city. The mayor and city attorney are elected directly by the voters of the entire city. The mayor, city attorney, and council members are elected to four-year terms, with a two-term limit.[150] Elections are held on a non-partisan basis per California state law; nevertheless, most officeholders do identify themselves as either Democrats or Republicans. In 2007, registered Democrats outnumbered Republicans by about 7 to 6 in the city,[151] and Democrats currently hold a 5–3 majority in the City Council.

San Diego is part of San Diego County, and includes all or part of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th supervisorial districts of the San Diego County Board of Supervisors,[152] Other county officers elected in part by city residents include the Sheriff, District Attorney, Assessor/Recorder/County Clerk, and Treasurer/Tax Collector.

Areas of the city immediately adjacent to San Diego Bay ("tidelands") are administered by the Port of San Diego, a quasi-governmental agency which owns all the property in the tidelands and is responsible for its land use planning, policing, and similar functions. San Diego is a member of the regional planning agency San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG). Public schools within the city are managed and funded by independent school districts (see above).

State and federal

In the state legislature San Diego is located in the 39th and 40th Senate Districts, represented by Democrats Marty Block and Ben Hueso.

Portions of San Diego are in the 77th, 78th, 79th and 80th Assembly Districts, represented by Republican Brian Maienschein and Democrats Toni Atkins, Shirley Weber and Lorena Gonzalez, respectively.

Federally, San Diego is located in California's 51st, 52nd, and 53rd congressional districts, which are represented by Democrats Juan Vargas, Scott Peters, and Susan Davis, respectively.

Major scandals

San Diego was the site of the 1912 San Diego Free Speech Fight, in which the city restricted speech, vigilantes brutalized and tortured anarchists, and the San Diego Police Department killed an IWW member.

In 1916, rainmaker Charles Hatfield was blamed for $4 million in damages and accused of causing San Diego's worst flood, during which about 20 Japanese American farmers died.[153]

Then-mayor Roger Hedgecock was forced to resign his post in 1985, after he was found guilty of one count of conspiracy and twelve counts of perjury, related to the alleged failure to report all campaign contributions.[154][155] After a series of appeals, the twelve perjury counts were dismissed in 1990 based on claims of juror misconduct; the remaining conspiracy count was reduced to a misdemeanor and then dismissed.[156]

A 2002 scheme to underfund pensions for city employees led to the San Diego pension scandal. This resulted in the resignation of newly re-elected Mayor Dick Murphy[157] and the criminal indictment of six pension board members.[158] Those charges were finally dismissed by a federal judge in 2010.[159]

On November 28, 2005, U.S. Congressman Randy "Duke" Cunningham resigned after being convicted on federal bribery charges. He had represented California's 50th congressional district, which includes much of the northern portion of the city of San Diego. In 2006, Cunningham was sentenced to a 100-month prison sentence.[160]

In 2005 two city council members, Ralph Inzunza and Deputy Mayor Michael Zucchet — who briefly took over as Acting Mayor when Murphy resigned – were convicted of extortion, wire fraud, and conspiracy to commit wire fraud for taking campaign contributions from a strip club owner and his associates, allegedly in exchange for trying to repeal the city's "no touch" laws at strip clubs.[161] Both subsequently resigned. Inzunza was sentenced to 21 months in prison.[162] In 2009, a judge acquitted Zucchet on seven out of the nine counts against him, and granted his petition for a new trial on the other two charges;[163] the remaining charges were eventually dropped.[164]

In July 2013, three former supporters of Mayor Bob Filner asked him to resign because of allegations of repeated sexual harassment.[165] Over the ensuing six weeks, 18 women came forward to publicly claim that Filner had sexually harassed them,[166] and multiple individuals and groups called for him to resign. On August 19 Filner and city representatives entered a mediation process, as a result of which Filner agreed to resign, effective August 30, 2013, while the city agreed to limit his legal and financial exposure.[167] Filner subsequently pleaded guilty to one felony count of false imprisonment and two misdemeanor battery charges, and was sentenced to house arrest and probation.[168][169]

Crime

San Diego was ranked as the 20th safest city in America in 2013 by Business Insider.[170] According to Forbes magazine, San Diego was the ninth-safest city in the top 10 list of safest cities in the U.S. in 2010.[171] Like most major cities, San Diego had a declining crime rate from 1990 to 2000. Crime in San Diego increased in the early 2000s.[172][173][174] In 2004, San Diego had the sixth lowest crime rate of any U.S. city with over half a million residents.[174] From 2002 to 2006, the crime rate overall dropped 0.8%, though not evenly by category. While violent crime decreased 12.4% during this period, property crime increased 1.1%. Total property crimes per 100,000 people were lower than the national average in 2008.[175]

According to Uniform Crime Report statistics compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 2010, there were 5,616 violent crimes and 30,753 property crimes. Of these, the violent crimes consisted of forcible rapes, 73 robberies and 170 aggravated assaults, while 6,387 burglaries, 17,977 larceny-thefts, 6,389 motor vehicle thefts and 155 arson defined the property offenses.[176]

LGBT culture

San Diego was named the ninth most LGBT-friendly city in the U.S. in 2013.[177] The city also has the seventh-highest percentage of gay residents in the U.S. Additionally in 2013, San Diego State University (SDSU), one of the city's prominent universities, was named one of the top LGBT-friendly campuses in the nation.[178]

As of August 30, 2013, when Todd Gloria became interim mayor, San Diego became the second-largest city in the country to have an openly gay mayor.[179][180]

Education

Public schools in San Diego are operated by independent school districts. The majority of the public schools in the city are served by the San Diego Unified School District, the second largest school district in California, which includes 11 K-8 schools, 107 elementary schools, 24 middle schools, 13 atypical and alternative schools, 28 high schools, and 45 charter schools.[181]

Several adjacent school districts which are headquartered outside the city limits serve some schools within the city; these include the Poway Unified School District, Del Mar Union School District, San Dieguito Union High School District and Sweetwater Union High School District. In addition, there are a number of private schools in the city.

Colleges and universities

According to education rankings released by the U.S. Census Bureau, 40.4 percent of San Diegans ages 25 and older hold bachelor's degrees. The census ranks the city as the ninth most educated city in the United States based on these figures.[182]

Public colleges and universities in the city include San Diego State University (SDSU), University of California, San Diego (UCSD), and the San Diego Community College District, which includes San Diego City College, San Diego Mesa College, and San Diego Miramar College. Private colleges and universities in the city include University of San Diego (USD), Point Loma Nazarene University (PLNU), Alliant International University (AIU), National University, California International Business University (CIBU), San Diego Christian College, John Paul the Great Catholic University, California College San Diego, Coleman University, University of Redlands School of Business, Design Institute of San Diego (DISD), Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising's San Diego campus, NewSchool of Architecture and Design, Pacific Oaks College San Diego Campus, Chapman University's San Diego Campus, The Art Institute of California-San Diego, Southern States University (SSU), UEI College, and Woodbury University School of Architecture's satellite campus.

There is one medical school in the city, the UCSD School of Medicine. There are three ABA accredited law schools in the city, which include California Western School of Law, Thomas Jefferson School of Law, and University of San Diego School of Law. There is also one unaccredited law school, Western Sierra Law School.

Libraries

The city-run San Diego Public Library system is headquartered downtown and has 34 branches throughout the city.[183] The libraries have had reduced operating hours since 2003 due to the city's financial problems. In 2006 the city increased spending on libraries by $2.1 million.[184] A new nine-story Central Library on Park Boulevard at J Street opened on September 30, 2013.[185]

In addition to the municipal public library system, there are nearly two dozen libraries open to the public which are run by other governmental agencies and by schools, colleges, and universities.[186] Noteworthy among them are the Malcolm A. Love Library at San Diego State University and the Geisel Library at the University of California, San Diego.

Media

The following are published within the city: the daily newspaper, U-T San Diego and its online portal, of the same name,[187] and the alternative newsweeklies, the San Diego CityBeat and San Diego Reader. Voice of San Diego is a non-profit online-only news outlet covering government, politics, education, neighborhoods, and the arts. The San Diego Daily Transcript is a business-oriented daily newspaper.

San Diego led U.S. local markets with 69.6 percent broadband penetration in 2004 according to Nielsen//NetRatings.[188]

San Diego's first television station was KFMB, which began broadcasting on May 16, 1949.[189] Since the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) licensed seven television stations in Los Angeles, two VHF channels were available for San Diego because of its relative proximity to the larger city. In 1952, however, the FCC began licensing UHF channels, making it possible for cities such as San Diego to acquire more stations. Stations based in Mexico (with ITU prefixes of XE and XH) also serve the San Diego market. Television stations today include XHTJB 3 (Once TV), XETV 6 (CW), KFMB 8 (CBS), KGTV 10 (ABC), XEWT 12 (Televisa Regional), KPBS 15 (PBS), KBNT-CD 17 (Univision), XHTIT 21 (Azteca 7), XHJK 27 (Azteca 13), KSDX-LP 29 (Spanish Independent), XHAS 33 (Telemundo), K35DG 35 (UCSD-TV), KDTF-LD 51 (Telefutura), KNSD 39 (NBC), KZSD-LP 41 (Azteca America), KSEX-CD 42 (Infomercials), XHBJ 45 (Canal 5), XHDTV 49 (MNTV), KUSI 51 (Independent), XHUAA 57 (Canal de las Estrellas), and KSWB-TV 69 (Fox). San Diego has an 80.6 percent cable penetration rate.[190]

Due to the ratio of U.S. and Mexican-licensed stations, San Diego is the largest media market in the United States that is legally unable to support a television station duopoly between two full-power stations under FCC regulations, which disallow duopolies in metropolitan areas with fewer than nine full-power television stations and require that there must be eight unique station owners that remain once a duopoly is formed (there are only seven full-power stations on the California side of the San Diego-Tijuana market).[citation needed] Though the E. W. Scripps Company owns KGTV and KZSD-LP, they are not considered a duopoly under the FCC's legal definition as common ownership between full-power and low-power television stations in the same market is permitted regardless to the number of stations licensed to the area. As a whole, the Mexico side of the San Diego-Tijuana market has two duopolies and one triopoly (Entravision Communications owns both XHAS-TV and XHDTV-TV, Azteca owns XHJK-TV and XHTIT-TV, and Grupo Televisa owns XHUAA-TV and XHWT-TV along with being the license holder for XETV-TV, which is run by California-based subsidiary Bay City Television).

San Diego's television market is limited to only San Diego county. The Imperial Valley has its own market (which also extends into western Arizona), while neighboring Orange and Riverside counties are part of the Los Angeles market. (Sometimes in the past, a missing network affiliate in the Imperial Valley would be available on cable TV from San Diego.)

The radio stations in San Diego include nationwide broadcaster, Clear Channel Communications; CBS Radio, Midwest Television, Lincoln Financial Media, Finest City Broadcasting, and many other smaller stations and networks. Stations include: KOGO AM 600, KFMB AM 760, KCEO AM 1000, KCBQ AM 1170, K-Praise, KLSD AM 1360 Air America, KFSD 1450 AM, KPBS-FM 89.5, Channel 933, Star 94.1, FM 94/9, FM News and Talk 95.7, Q96 96.1, KyXy 96.5, Free Radio San Diego (AKA Pirate Radio San Diego) 96.9FM FRSD, KSON 97.3/92.1, KIFM 98.1, Jack-FM 100.7, 101.5 KGB-FM, KPRI 102.1, Rock 105.3, and another Pirate Radio station at 106.9FM, as well as a number of local Spanish-language radio stations.

Infrastructure

Utilities

Water is supplied to residents by the Water Department of the City of San Diego. The city receives its water from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

Gas and electric utilities are provided by San Diego Gas & Electric, a division of Sempra Energy.

Street lights

In the middle part of the 20th century the city had mercury vapor street lamps. In 1978 the city decided to replace them with more efficient sodium vapor lamps. The proposal triggered an outcry from astronomers at Palomar Observatory 60 miles north of the city; they said the proposed lamps would increase light pollution and interfere with astronomical observation.[191] The city altered its lighting regulations to limit light pollution within 30 miles of Palomar.[192]

In 2011, the City announced plans to upgrade 80% of its street lighting to new energy-efficient street lights which use induction technology, a modified form of fluorescent lamp that produces a broader spectrum than sodium-vapor lamps. The new system is predicted to save $2.2 million per year in energy and maintenance costs.[193] The city stated the changes would "make our neighborhoods safer."[193] They also increase light pollution.[194]

In 2014, San Diego announced plans to become the first U.S. city to install cyber-controlled street lighting, using an "intelligent" lighting system to control 3,000 LED street lights.[195]

Transportation

With the automobile being the primary means of transportation for over 80 percent of its residents, San Diego is served by a network of freeways and highways. This includes Interstate 5, which runs south to Tijuana and north to Los Angeles; Interstate 8, which runs east to Imperial County and the Arizona Sun Corridor; Interstate 15, which runs northeast through the Inland Empire to Las Vegas; and Interstate 805, which splits from I-5 near the Mexican border and rejoins I-5 at Sorrento Valley.

Major state highways include SR 94, which connects downtown with I-805, I-15 and East County; SR 163, which connects downtown with the northeast part of the city, intersects I-805 and merges with I-15 at Miramar; SR 52, which connects La Jolla with East County through Santee and SR 125; SR 56, which connects I-5 with I-15 through Carmel Valley and Rancho Peñasquitos; SR 75, which spans San Diego Bay as the San Diego-Coronado Bridge, and also passes through South San Diego as Palm Avenue; and SR 905, which connects I-5 and I-805 to the Otay Mesa Port of Entry.

The stretch of SR 163 that passes through Balboa Park is San Diego's oldest freeway, and has been called one of America's most beautiful parkways.[196]

San Diego's roadway system provides an extensive network of routes for travel by bicycle. The dry and mild climate of San Diego makes cycling a convenient and pleasant year-round option. At the same time, the city's hilly, canyon-like terrain and significantly long average trip distances—brought about by strict low-density zoning laws—somewhat restrict cycling for utilitarian purposes. Older and denser neighborhoods around the downtown tend to be utility cycling oriented. This is partly because of the grid street patterns now absent in newer developments farther from the urban core, where suburban style arterial roads are much more common. As a result, a vast majority of cycling-related activities are recreational. Testament to San Diego's cycling efforts, in 2006, San Diego was rated as the best city for cycling for U.S. cities with a population over 1 million.[197]

San Diego is served by the San Diego Trolley light rail system,[198] by the SDMTS bus system,[199] and by Coaster[200] and Amtrak Pacific Surfliner[201] commuter rail; northern San Diego county is also served by the Sprinter light rail line.[202] The Trolley primarily serves downtown and surrounding urban communities, Mission Valley, east county, and coastal south bay. A planned Mid-Coast extenstion of the Trolley will operate from Old Town to University City and the University of California, San Diego along the I-5 Freeway, with planned operation by 2018. The Amtrak and Coaster trains currently run along the coastline and connect San Diego with Los Angeles, Orange County, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura via Metrolink and the Pacific Surfliner. There are two Amtrak stations in San Diego, in Old Town and the Santa Fe Depot downtown. San Diego transit information about public transportation and commuting is available on the Web and by dialing "511" from any phone in the area.[203]

The city's primary commercial airport is the San Diego International Airport (SAN), also known as Lindbergh Field. It is the busiest single-runway airport in the United States.[204] It served over 17 million passengers in 2005, and is dealing with an increasingly larger number every year.[204] It is located on San Diego Bay three miles (4.8 km) from downtown. San Diego International Airport maintains scheduled flights to the rest of the United States including Hawaii, as well as to Mexico, Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom. It is operated by an independent agency, the San Diego Regional Airport Authority. In addition, the city itself operates two general-aviation airports, Montgomery Field (MYF) and Brown Field (SDM).[205]

Numerous regional transportation projects have occurred in recent years to mitigate congestion in San Diego. Notable efforts are improvements to San Diego freeways, expansion of San Diego Airport, and doubling the capacity of the cruise ship terminal of the port. Freeway projects included expansion of Interstates 5 and 805 around "The Merge," a rush-hour spot where the two freeways meet. Also, an expansion of Interstate 15 through the North County is underway with the addition of high-occupancy-vehicle (HOV) "managed lanes". There is a tollway (The South Bay Expressway) connecting SR 54 and Otay Mesa, near the Mexican border. According to a 2007 assessment, 37 percent of streets in San Diego were in acceptable driving condition. The proposed budget fell $84.6 million short of bringing the city's streets to an acceptable level.[206] Port expansions included a second cruise terminal on Broadway Pier which opened in 2010. Airport projects include expansion of Terminal 2, currently under construction and slated for completion in summer 2013.[207]

Notable people

Sister cities

San Diego has 16 sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:[208][209]

Alcalá de Henares, Spain

Alcalá de Henares, Spain Campinas, Brazil

Campinas, Brazil Cavite, Philippines

Cavite, Philippines Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom[210][211]

Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom[210][211] Jalalabad, Afghanistan

Jalalabad, Afghanistan Jeonju, South Korea

Jeonju, South Korea León, Mexico

León, Mexico Perth, Australia

Perth, Australia Quanzhou, China[209]

Quanzhou, China[209] Taichung City, Taiwan

Taichung City, Taiwan Tema, Ghana

Tema, Ghana Tijuana, Mexico

Tijuana, Mexico Vladivostok, Russia

Vladivostok, Russia Warsaw, Poland[212]

Warsaw, Poland[212] Yantai, China

Yantai, China Yokohama, Japan[213]

Yokohama, Japan[213]

See also

- 1858 San Diego hurricane

- List of notable San Diegans

- Category:Visitor attractions in San Diego County, California

- Category: Museums in San Diego County

References

- ^ U.S. Census

- ^ Balk, Gene (May 23, 2013). "Census: Seattle among top cities for population growth | The Today File | Seattle Times". Blogs.seattletimes.com. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ McGrew, Clarence Alan (1922). City of San Diego and San Diego County: the birthplace of California. American Historical Society. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ "New York City tops in population; 8 more cities above 1M - The Business Journals". Bizjournals.com. April 5, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Gallegos, Dennis R. (editor). 1987. San Dieguito-La Jolla: Chronology and Controversy. San Diego County Archaeological Society, Research Paper No. 1.

- ^ "Kumeyaay indians". kumeyaay.info. Retrieved July 1, 2010.[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Lesson Plan: For the Last 10,000 Years…" (PDF). National

Estuarine Research Reserves via NOAA. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 9 (help) - ^ "San Diego Historical Society". Sandiegohistory.org. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ "Journal of San Diego History, October 1967". Sandiegohistory.org. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ "San Diego Historical Society:Timeline of San Diego history". Sandiegohistory.org. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Keyfacts". missionscalifornia.com. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Mission San Diego". Mission San Diego. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "National Park Service, National Historicl Landmarks Program: San Diego Presidio". Tps.cr.nps.gov. October 10, 1960. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ San Diego Historical Society timeline

- ^ Richard Griswold del Castillo, The U.S.-Mexican War in San Diego, 1846-1847; The Journal of San Diego History, SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY, Winter 2003, Volume 49, Number 1

- ^ Griswold de Castillo, Richard (1990). The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-8061-2478-4.

- ^ "City of San Diego website". Sandiego.gov. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Engstrand, Iris Wilson, California’s Cornerstone, Sunbelt Publications, Inc. 2005, p. 80. May 30, 2005. ISBN 978-0-932653-72-7. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Steele, Jeanette (May 1, 2005). "Balboa Park future is full of repair jobs". The San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Marjorie Betts Shaw,. "The San Diego Zoological Garden: A Foundation to Build on". Journal of San Diego History. 24 (3, Summer 1978). Sandiegohistory.org. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Historic California Posts: Fort Rosecrans". California State Military Museum. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ University of San Diego: Military Bases in San Diego

- ^ a b Gerald A. Shepherd,. "When the Lone Eagle returned to San Diego". Journal of San Diego History. 40 (s. 1 and 2, Winter 1992). Sandiegohistory.org. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow, 1996, 54.

- ^ "Milken Institute". Milken Institute. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "San Diego History Center Honors San Diego's Tuna Fishing Industry at Annual Gala". San Diego History Center. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Felando, August and Medina, Harold (Winter–Spring 2012). "The Origins of Califonia's High-Seas Tuna Fleet". The Journal of San Diego History. 58 (1 & 2). San Diego History Center: 5–8, 18. ISSN 0022-4383.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lechowitzky, Irene (November 19, 2006). "It's the old country, with new condos". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Crawford, Richard (June 20, 2009). "San Diego once was 'Tuna Capital of World'". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Erie, Steven P.; Kogan, Vladimir; MacKenzi, Scott A. (January 27, 2010). "Redevelopment, San Diego Style: The Limits of Public–Private Partnerships". Urban Affairs Review. 45 (5): 644–678. doi:10.1177/1078087409359760. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marshall, Monte. "The Geology and Tectonic Setting of San Diego Bay, and That of the Peninsular Ranges and Salton Trough, Southern California". Phil Farquharson. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ "Canyon Enhancement Planning Guide" (PDF). San Diego Canyonlands. p. 7. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Schad, Jerry. Afoot and Afield in San Diego. Wilderness Press, Berkeley, Calif. p. 111. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ “Report: San Diego has 9th best parks among survey of 50 U.S. cities” June 6, 2013. ABC 10 News. Retrieved on July 18, 2013.

- ^ "City of San Diego Community Planning Areas". Sandiego.gov. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "Aitken, Stuart, and Prosser, Rudy, ',Residents' Spatial Knowledge of Neighborhood Continuity and Form',, Geographical Analysis, September 3, 2010". September 3, 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4632.1990.tb00213.x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Roger Showley (April 18, 2010). "City, SANDAG win planning awards". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ Engstrand, Iris Wilson, California’s Cornerstone. Sunbelt Publications, Inc. 2005. p. 80. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "San Diego Timeline Diagram". Skyscraper Source Media. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ "One America Plaza". Emporis.com. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ "Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan for San Diego International Airport" (PDF). San Diego County Regional Airport Authority. October 4, 2004. pp. 51–52. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ^ Bergman, Heather (June 27, 2005). "San Diego's skyline grows up: residential towers filling some of the missing 'tools' as office projects are nearing completion". San Diego Business Journal. The Heritage Group. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ Geiger, Peter (October 5, 2006). "The 10 Best Weather Cities". Farmer’s Almanac. Almanac Publishing. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

- ^ Kellogg, Becky and Erdman, Jonathan (September 2010). "America's Best Climates". The Weather Channel. Retrieved April 19, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. Kottek; J. Grieser, C. Beck, B. Rudolf, and F. Rubel (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorol. Z. 15: 259–263. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Atlas of the Biodiversity of California. California Department of Fish and Game. p.15.

- ^ Francisco Pugnaire and Fernando Valladares eds. Functional Plant Ecology. 2d ed. 2007. p.287.

- ^ Michael Allaby, Martyn Bramwell, Jamie Stokes, eds. Weather and Climate: An Illustrated Guide to Science. 2006. p.182.

- ^ Michalski, Greg et al. First Measurements and Modeling of ∆17O in atmospheric nitrate. Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 30, No. 16. p.3. 2003.

- ^ "UCSD". Meteora.ucsd.edu. May 14, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for San Diego, CA". The Weather Channel. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Monthly Averages for El Cajon, CA". The Weather Channel. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Lee, Mike (June 18, 2011). "Is global warming changing California Current?". U-T (San Diego Union Tribune). Retrieved June 20, 2011.

- ^ "San Diego's average rainfall set to lower level". San Diego Union-Tribune. March 16, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Rowe, Peter (December 13, 2007). "The day it snowed in San Diego". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ "National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency: San Diego climate by month". Wrh.noaa.gov. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- ^ Conner, Glen. History of weather observations San Diego, California 1849—1948. Climate Database Modernization Program, NOAA's National Climatic Data Center. pp. 7–8.

- ^ "National Weather Service Forecast Office - NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved October 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "San Diego/Lindbergh Field CA Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ Wells, Michael L.; John F. O'Leary, Janet Franklin, Joel Michaelsen, and David E. McKinsey (November 2, 2004). "Variations in a regional fire regime related to vegetation type in San Diego County, California (USA)". Landscape Ecology. 19 (2). San Diego, CA 92182-4493, USA: Springer Netherlands: 139–152. doi:10.1023/B:LAND.0000021713.81489.a7. 1572-9761. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Strömberg, Nicklas; Michael Hogan (November 29, 2008). "Torrey Pine: Pinus torreyana". GlobalTwitcher. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Tecolote Canyon Natural Park & Nature Center". The City of San Diego. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "Marian Bear Memorial Park". The City of San Diego. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ Lee, Mike (March 28, 2007). "White House seeks limits to species act". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "San Diego County Bird Atlas Project". San Diego Natural History Museum.[dead link]

- ^ "Corpus Christi Recognized as Birdiest City". Corpus Christi Daily. December 2004. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ "Corpus Christi remains 'birdiest city in America'". Corpus Christi Convention and Visitors Bureau. June 25, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ Goldstein, Bruce Evan (September 2007). "The Futility of Reason: Incommensurable Differences Between Sustainability Narratives in the Aftermath of the 2003 San Diego Cedar Fire". Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning. 9 (3 & 4). Blacksburg, USA: School of Public and International Affairs, Virginia Tech: 227–244. doi:10.1080/15239080701622766. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ^ "CalFire website". Fire.ca.gov. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Viswanathan, S.; L. Eria, N. Diunugala, J. Johnson, C. McClean (January 2006). "An Analysis of Effects of San Diego Wildfire on Ambient Air Quality". Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association. 56 (1). Retrieved December 15, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manolatos, Tony (October 22, 2007). "Wildfires seen as eclipsing the Cedar fire of 2003". San Diego Union Tribune. Signonsandiego.com. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places Over 100,000, Ranked by July 1, 2009 Population: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. July 1, 2009. Archived from the original (CSV) on June 27, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Census: 1,307,402 Live in San Diego (March 8, 2011). "Voice of San Diego, March 8, 2011". Voiceofsandiego.org. Retrieved May 4, 2011.