Race of ancient Egyptians

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

The race of ancient Egyptians is a controversial topic of debate aimed at identifying the racial identity of ancient Egyptians due to rise of Afrocentrism. Although ancient Egypt was a cosmopolitan society, consisting of people of different ancetries, there is an effort to identify a single race to which the majority of ancient Egyptians belonged.

Ancient Egypt is believed to have been populated either by dark-skinned or "black" people (people of sub-Saharan and West Africa and portions of North Africa), or light-skinned or "white" people (people of Europe, North Africa, Western Asia, some of South Asia and portions of Central Asia). Many disagree on the proportions and contributions of these groups.

Overview of theories

Some scholars, mostly Afrocentrists, believe that the character of the Egyptian society and culture most closely resembled that of African cultures. [citation needed] They also assert that Egypt remained essentially a "black" African civilization throughout the dynastic era.[citation needed] This is based on re-reading debatable archaeological evidence pointing to Nubian, Badarian, and older Saharan cultures whose religious and cultural practices most closely resemble Egypt's own, to serve a political aspiration.[citation needed]

Others, however, have focused less on cultural aspects and more on underlining comparisons with other groups (skull shapes and non-phenotyic DNA affiliations). In this aspect they believe that the "black" presence of Egypt has been substantial.[citation needed]

Yet some genetic studies show that there is little change in ethnic distirbution between ancient and modern Egyptians.[1] [2] [3] [4] This claim invariably leads to a debate about the race of modern Egyptians.

Finally there are those who have been reluctant to assign racial designations or make definitive claims about the skin color of its inhabitants at all.

Obstacles in ascertaining race

Determining the race of ancient Egyptians is rife with difficulties. Racial categories are based mostly on genetics and traced through mutations; additionally they are based on phenotype, lineage and geography. It is within this framework that the discussion of the racial identity of ancient Egyptians is generally framed.

In addition, racial categories are themselves hard to define. The terms Caucasoid, Negroid, and Mongoloid are widely discredited by opponents of racism. Likewise, black and white are not precisely defined, as skin tone varies within a single race (see below). Even a term such as "African" is considered inappropriate, and must be framed as "from sub-Saharan and West Africa and portions of North Africa".

Skin color

Skin color within a single racial category can fall within a broad spectrum of shades. For historical reasons, blackness and whiteness are particularly difficult concepts to describe definitively in Western societies. Racist remnants of earlier times, such as the one-drop theory and colonialism, still influence the racial perceptions of multiracial individuals. In the case of dynastic Egypt, this approach, of defining certain dark-skinned populations as non-black has extended to indigenous Africans, an approach which has drawn sharp criticism and ridicule in certain academic circles.

Condition and availablity of remains

The remains of ancient Egyptians available for study today generally have deteriorated significantly and have been subjected to embalming. While scientific testing and forensic examination provide many clues, the debate over the racial identity of dynastic Egypt continues. DNA testing allows for broad categorizations based on haplogroup. In the 21st century, forensic reconstructions have produced widely varying images and castings of what Pharaoh Tutankhamun may have looked like, but critics charge that some of these efforts have been politically and racially motivated and have produced deliberately inaccurate representations[citation needed]. But even if researchers could determine conclusively the ethnicity of a single pharaoh, the questions of the ethnicity of the broader Egyptian population over the millennia would remain[citation needed]. Though non-royal remains have been unearthed, researchers stand little chance of unearthing a true cross-section of Egyptian society[citation needed], but in any case, most high-profile bickering has centered around the icons of ancient Egypt -- its pharaohs as well as their Queens regnant and Queen consorts.

Geography and linguistics

Geographical and linguistic evidence hold some clues, but the proximity of Egypt to the Middle East and Asia resulted in a confluence of cultures and peoples, where the balance of power and influence of these disparate elements changed constantly over the millennia spanned by dynastic Egypt.

Art

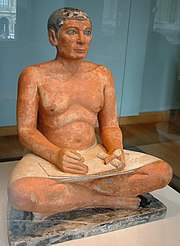

The art of the ancient Egyptians is a rich cultural legacy, providing ample evidence of Egyptian daily social, political economic and religious life. Egyptian artisans were highly skilled metalsmiths, painters, carvers and sculptors. However, Egyptian aesthetics and the use of clearly symbolic, rather than realistic, colors in some instances when depicting the human form have made determinations of the racial identity of subjects problematic in some cases. Human figures have been depicted in yellow ochre, a brownish red ochre, blue, white and black. Various scholars have offered differing interpretations regarding the meaning and purpose of such depictions, and the matter of race remains unsettled. Compounding the problem is the elitist nature of much of the art that has endured. Murals and artifacts in temples and crypts constructed to honor deceased royalty and the politically powerful may not accurately reflect the demographics of the majority of the Egyptian populace of the time.

Politics

Beyond the scientific difficulties is the matter of politics. Different factions have attempted to cast ancient Egyptians in their own image, claiming dynastic Egypt as the creation of their ancestors. Even those who agree that Egypt was a multi-ethnic society at least at some point in history disagree over when population shifts may have occurred and extent to which ethnic diversity existed, and recriminations have been leveled by one group against another, charging cultural appropriation. In 2005, when three, separate teams from three different nations were charged with reconstructing the face of Tutankhamun and assigning a racial and geographic point of origin, a furor and angry protests by American blacks erupted amid charges of Afrophobia on the part of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, racism, "whitewashing" and counter charges of "reverse racism."[citation needed]

Genetic evidence

Full scale, comparative forensic analysis and DNA testing of mummies may help identify the race of the ancient Egyptians, but thus far only a limited number of mummies have been tested.

Modern Egyptians

Some genetic studies suggest that there is little change in ethnic distribution between ancient Egyptians and modern Egyptians.[5] [6] [7] [8]

To further confuse matters, there is debate over how to classify the race of modern Egyptians, In general, they are classified as predominantly North African, Caucasian, Southern European, or Western Eurasian[9] [10] [11], with evidence for gene flow from Ethiopia. Numerous genetic tests have been performed on the Egyptians in order to determine their origins. One maternal study linked Egyptians with people from Ethiopia.[1] There was also a Y chromosme study by Lucotte et al performed on Egyptians, with haplotypes V, XI, and IV being most common. Haplotype V is common in Berbers and has a low frequency outside Africa. [2] Haplotypes V and XI, and IV are all supra/sub-Saharan horn of African haplotypes, and they are far more dominant in Egyptians than Near Eastern or European haplotypes. [3] [12]

- Cavalli-Sforza et al. (1994) compared populations from throughout the world using extensive genetic data. The North African populations grouped with West Eurasian (European, Middle East) populations rather than sub-Saharan Africans.

- Di Rienzo et al. (1994) studied the relationship of three samples (taken from Egyptians, Sardinians, and sub-Saharan Africans), using mitochondrial DNA and simple sequence repeats. In terms of genetic distance, the Egyptian sample was closer to the Sardinian sample than to the sub-Saharan African sample.

- Hammer et al. (1997) used seven different methods to compute population trees of world populations, using Y-chromosome data. All seven methods grouped the Egyptians with the non-African populations rather than with the sub-Saharan Africans. Egyptians' genetic profile resembles that of South Europeans more than the other regional groups in the study.

- Poloni et al. (1997). Egyptians and a few other African populations (Tunisians, Algerians, and even Ethiopians) showed a stronger Y-chromosome similarity to non-African Mediterraneans than to the remainder of Africans mostly from south of the Sahara.

- Bosch et al. (1997), using classical genetic markers, calculated Egyptians to be genetically very close to Mediterranean Asians and Europeans.[4]

Other analysis of mummified remains

Melanin tests

Cheikh Anta Diop's forensic tests of melanin content in Egyptian mummies and of forensic reconstruction of skulls are cited as evidence that the early dynastic Egyptians were black Africans and remained so in predominant part for millennia. Supporters of Diop's claims assert that similar tests for determining the melanin content in bones have been used by police departments in the gathering of forensic evidence around the world, albeit using remains thousands of years younger.[citation needed]

Melanin content alone is not definitive evidence of ethnicity, but when placed in the context of the possible Nile Valley populations of the time, many consider Diop's findings compelling. Critics argue that relatively few examples of well-preserved human remains of the era exist, and that the degradation of melanin over time and in the presence of ancient embalming fluids is a phenomenon that has not been widely studied. Diop himself addressed the subject in Origin of the Ancient Egyptians:

Melanin (eumelanin), the chemical body responsible for skin pigmentation, is, broadly speaking, insoluble and is preserved for millions of years in the skins of fossil animals. There is thus all the more reason for it to be readily recoverable in the skins of Egyptian mummies, despite a tenacious legend that the skin of mummies, tainted by the embalming material, is no longer susceptible of any analysis. Although the epidermis is the main site of the melanin, the melanocytes penetrating the derm at the boundary between it and the epidermis, even where the latter has mostly been destroyed by the embalming materials, show a melanin level which is non-existent in the white-skinned races....

Either way let us simply say that the evaluation of melanin level by microscopic examination is a laboratory method which enables us to classify the ancient Egyptians unquestionably among the black races.[5]

Tutankhamen

In December 2000, a team of Japanese scientists received approval to DNA test Tutankhamen.[6] However, Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities reversed their decision to allow testing.[7] In 2004, forensic testing was again planned and halted.[8]

Cultural and religious evidence

Some scholars cite evidence of African culture in ancient Egyptian society. According to the 1974 Encyclopaedia Britannica:

"In Libya, which is mostly desert and oasis, there is a visible Negroid element in the sedentary populations, and at the same is true of the Fellahin of Egypt, whether Copt or Muslim. Osteological studies have shown that the Negroid element was stronger in predynastic times than at present, reflecting an early movement northward along the banks of the Nile, which were then heavily forested." Fellahin, in fact, is the name Arabs traditionally gave to the indigenous peoples of the lands they conquered. The term means tiller or peasant. (Encyclopaedia Britannica 1974 ed. Macropedia Article, Vol 14: "Populations, Human" - page 843) "A large number of gods go back to prehistoric times. The images of a cow and star goddess, (Hathor), the falcon (Horus), and the human-shaped figures of the fertility god (Min) can be traced back to that period. Some rites, such as the "running of the Apil-bull," the "hoeing of the ground," and other fertility and hunting rites (e.g., the hippopotamus hunt) presumably date from early times.. Connections with the religions in southwest Asia cannot be traced with certainty. It is doubtful whether Osiris can be regarded as equal to Tammuz or Adonis, or whether Hathor is related to the "Great Mother."(Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1974 ed., Macropedia Article, Vol 6: "Egyptian Religion" , pg 508.)

The ancient Egyptians themselves traced their origin to a land they called "Punt" (pwnt), or ta nṯrw (read "Ta Netcherew"), the "Land of the Gods". Punt is thought to have been located around the Sudanese-Eritrean border. A wall relief of Puntite royalty reveals a dark brown-skinned king and queen, the latter exhibiting the characteristic attributes of a Khoisan woman.[9] Commerce existed between Egypt and Punt, with Egyptian royalty mounting expeditions to what they regarded as their ancestral home. Among the items they brought back were whole trees of myrrh and other species, aromatic woods, incense, leopards, monkeys, ivory, ebony, panther hides, cinnamon and gum.

There are closer relations with northeast African religions. The numerous animal cults (especially bovine cults and panther gods) and details of ritual dresses (animal tails, masks, grass aprons, etc) probably are of African origin. The kinship in particular shows some African elements, such as the king as the head ritualist (i.e., medicine man), the limitations and renewal of the reign (jubilees, regicide), and the position of the king's mother (a matriarchal element). Some of them can be found among the Ethiopians in Napata and Meroe, others among the Prenilotic tribes (Shilluk)."

…the Egyptians may have brought back more than goods from Punt, for it has often been suggested that their well known pygmy god, Bes, may have also been a Punt import. It would seem probably that dwarfs and pygmies were indeed imported from Punt, for an inscription in the tomb of Harkhuf, and expedition leader under Pepy II, tells of his acquisition of a dwarf for that king.[10]

Wrote historian Drusilla Houston in her 1926 work The Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire:

Strabo mentions the Nubians as a great race west of the Nile. They came originally from Kordofan, whence they emigrated two thousand years ago. They have rejected the name Nubas as it has become synonymous with slave. They call themselves Barabra, their ancient race name. Sanskrit historians call the Old Race of the Upper Nile Barabra. These Nubians have become slightly modified but are still plainly Negroid. They look like the Wawa on the Egyptian monuments. The Retu type number one was the ancient Egyptian, the Retu type number two was in feature an intermingling of the Ethiopian and Egyptian types. The Wawa were Cushites and the name occurs in the mural inscriptions five thousands years ago. Both people were much intermingled six thousand years ago. The faces of the Egyptians of the Old Monarchy are Ethiopian but as the ages went on they altered from the constant intermingling with Asiatic types. Also the intense furnace-like heat of Upper Egypt tended to change the features and darken the skin. In the inscriptions relative to the campaigns of Pepi I, Negroes are represented as immediately adjoining the Egyptian frontier. This seems to perplex some authors. They had always been there. This was the Old Race of predynastic Egypt—the primitive Cushite type. This was the aboriginal race of Abyssinia. It was symbolized by the Great Sphinx and the marvelous face of Cheops. Take any book of Egyptian history containing authentic cuts and examine the faces of the first pharaohs, they are distinctively Ethiopian. The "Agu" of the monuments represented this aboriginal race. They were the ancestors of the Nubians. and were the ruling race of Egypt. Petrie in 1892 exhibited before the British Association, some skulls of the Third and Fourth Dynasties, showing distinct Negroid characteristics. They were dolichocephalic or long skulled. The findings of archaeology more and more reveal that Egypt was Cushite in her beginning and that Ethiopians were not a branch of the Japheth race in the sense that they are so represented in the average ethnological classifications of today.[11]

Textual evidence

Western classical writers usually described Egyptians as a mid-tone between black Ethiopians and pale Europeans.[citation needed]

Marcus Manilius states that "the Ethiopians stain the world and depict a race of men steeped in darkness. Less sun-burnt are the natives of India. The land of Egypt, flooded by the Nile, darkens bodies more mildly owing to the inundation of its fields: it is a country nearer to us and its moderate climate imparts a medium tone." Professor of Classics, Frank M. Snowden Jr., Howard University, comments:

Here the term Ethiopians (= Greek "burnt face", denoting very dark skin) refers to Africans inhabiting latitudes south of Egypt. The term "Ethiopian," in that it was a broad category encompassing diverse ethnic groups of tropical Africa, was similar to a modern-day "racial" designation and roughly corresponded to what early anthropologists would have called "Negro." Yet classical writers, as exemplified by Manilius' quote above, clearly differentiated the Egyptians from "Ethiopians." Philostratus, for example, noted that a people living near the Nubian border were lighter than Ethiopians, and that Egyptians were lighter still.[12]

While Herodotus referred to the dark skin and woolly hair of the Egyptians, detailed microscopic investigations of hair samples taken from several ancient Egyptian mummies suggest that "Only a minority showed evidence of structural characteristics traditionally called "Negroid"; even in these the "Negroid" elements were weakly manifested" (Titlbachova and Titlbach, 1977)

Joann Fletcher, a consultant to the Bioanthropology Foundation in the UK, in what she calls an "absolute, thorough study of all ancient Egyptian hair samples" — relied on various techniques, such as electron microscopy and chromatography to analyze hair samples (Parks, 2000). She discovered that most of the natural hair types and those used for hairpieces were made of what she calls "Caucasian-type" hair, including even instances of blonde and red hair. Fletcher surmises that some of the lighter hair types may have been influenced by the presence of ancient Libyans and Greeks in ancient Egypt. However, this type of hair was also found to be present in much earlier times. (Parks, Lisa. 2000. Ancient Egyptians Wore Wigs. Egypt Revealed Magazine (www.egyptrevealed.com), May 29) [13]

Linguistic evidence

The ancient Egyptian language is a member of the Afro-Asiatic family (otherwise called "Hamito-Semitic") - a language group that covers most of North Africa, the Horn of Africa, Chad and Nigeria as well as the Middle East. As a result, speakers of Afro-Asiatic languages are multi-ethnic and possess a wide range of skin colors.

Some Afrocentrist scholars point out an additional affinity of Egyptian with languages of the Niger-Congo family, virtually all the speakers of which are blacks. For example, Cheikh Anta Diop claims that the ancient Egyptian language has vocabulary in common with Wolof, while Théophile Obenga links it with Mbochi. These efforts are unrelated to mainstream linguistics, which discredits mere listing of similar-sounding or possibly related terms in different languages;accepting only rigorous investigations based on the methodology of historical linguistics, in particular the comparative method. Furthermore, quite apart from the merits of the linguistic argument, the practice of positing racial or genetic identity based on linguistic evidence is utterly discredited.

Kemet — "black land"

| km biliteral | km.t (place) | km.t (people) | |||||||||

|

|

|

One of the many names for Egypt in Ancient Egyptian is km.t (read "Kemet"), meaning "black land". More literally, the word means "black thing": km means "black" and the t-suffix indicates an abstract noun formed from an adjective. The chief component of the word is usually a sign (biliteral km) depicting what is either a terraced bank of the Nile (the fertile black soil of the most hospitable part of Egypt), or the tail of a crocodile.

The use of km.t "black land" in terms of a place was generally in contrast to the "red land": the desert beyond the Nile valley. When used to mean people, km.t "people of Kemet", "people of the black land" is usually translated "Egyptians". The Ancient Egyptians occasionally called themselves kmm.w (read "Kememew"), "the black people", omitting the t-suffix.[citation needed]

Geographic evidence

Opponents of Afrocentrism often argue that Egyptians belong among the ethnically Semitic peoples of the Middle East, pointing to the fact that Egypt is at the extreme north eastern edge of the African continent, close to both Israel and the Arabian Peninsula. However, rather than being comprised of a singular people, Egypt also extends south into areas occupied by undeniably black-skinned people, like Sudan.

It is commonly accepted that the population of Egypt was, at least in later dynasties, a mixture of black African, Mediterranean, Semitic and, even later, European peoples.[citation needed] However, these very categories are disputable and indeterminate.

Skin color among various populations of indigenous Africans differs naturally. Today, a brown-skinned Fula is generally considered no less a black African than a very dark-skinned Nubian. Afrocentrists argue that the same can be said of Nubians and Egyptians. In fact, prognathism — a forward-slanting facial profile — is a key indicator used by forensic experts today to assign racial identity [citation needed]. It would be strange to Afrocentricists that Eurocentric scholars will classify people like African-Americans, Fulani, and others as "black" people who resemble Egyptians who they consider to be non-black caucasoids[citation needed].

Significantly, however, all aspects of the standard Africoid phenotype of coarse, curly hair; broad, flat noses and full lips do not apply to all black peoples, many of whom have relatively straight hair and narrower facial features. While these peoples possess a range of skin tones and some diverge from the classically Africoid phenotype, they are considered no less "Negro", no less black, than other autochthonous peoples of the African continent— many of the Nilotic, linguistically Semitic and Cushitic speaking peoples of both North East Africa and East Africa being examples.[citation needed] Among humankind, no other racial group has greater phenotypical biodiversity than do Africoid peoples.[citation needed] Further, these indigenous, black, African peoples of the Nile Valley all comprised in part—and Afrocentrists believe in predominant part—the ethnically diverse peoples of ancient dynastic Egypt.[citation needed] It must also be emphasized, that contrary to popular sentimentalized stories, the conflict between Egypt and Nubia was hardly "racial", many egyptians that had the stereotypical "negro appearance" weren't even called "Nehesy". (the ancient egyptian word for Nubian). [14] Rather interestingly, the dynasties (like the 12th) in which the strongest invectives were taken against Nubians, were in fact, Nubian themselves in origin or at least had origins in areas that were on the border with Nubia, like Aswan. [15] It's also been confirmed that the Egyptians were closest ethnically to the Nubians[citation needed], since they shared similar political and cultural institutions during the predynastic period.

Artistic evidence

Artistic renderings of the human form in dynastic Egyptian art were produced using a variety of pigments, ranging from yellow through auburn to black — or even blue. In some instances, the selection of skin tones was symbolic and meant to convey vitality, strength, feminity, permanence, and even death. Gaston Maspero writes about Nofrîtari, who reigned conjointly with Amenôthes:

"Her statue in the Turin Museum represents her as having black skin. She is also painted black standing before Amenôthes (who is white) in the Deir el-Medineh tomb, now preserved in the Berlin Museum, in that of Nibnûtîrû, and hi that of Unnofir, at Sheikh Abd el-Qûrnah. Her face is painted blue in the tomb of Kasa. The representations of this queen with a black skin have caused her to be taken for a negress, the daughter of an Ethiopian Pharaoh, or at any rate the daughter of a chief of some Nubian tribe; it was thought that Ahmosis must have married her to secure the help of the negro tribes in his wars, and that it was owing to this alliance that he succeeded in expelling the Hyksôs. Later discoveries have not confirmed these hypotheses. Nofrîtari was most probably an Egyptian of unmixed race, as we have seen, and daughter of Ahhotpû I., and the black or blue colour of her skin is merely owing to her identification with the goddesses of the dead." (Gaston Maspero, History of Egypt, Chaldæa, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, Volume IV, Part A)

In typical portrayals of Egyptians in their own art, from the Old Kingdom onwards they appear anywhere from auburn to deeply brown-skinned, using a red ochre and black pigment; women are typically depicted as having lighter, yellow skin color. Some walking stick handles and several tomb decorations depicted conquered adversaries, representing defeated Asiatic and Africoid enemies. [16] Donnelly considered the murals to show that the Egyptians had a reddish hue:

"The ancient Egyptians were red men. They recognized four races of men--the red, yellow, black, and white men. They themselves belonged to the "Rot," or red men; the yellow men they called "Namu"--it included the Asiatic races; the black men were called "Nahsu," and the white men "Tamhu." (Ignatius Donnelly, Atlantis, the Antediluvian World, 1882, p. 195)

Ray Johnson, director of the University of Chicago's research center at Luxor, describes the quartzite head of an egyptian princess as "most likely a family trait exaggerated by the artistic style of the period" and that it "It simply falls within the normal range of human variation." [17]

The Great Sphinx of Giza

The Great Sphinx of Giza, thought to be a likeness of the Pharaoh Khufu, is in considerable disrepair after over four thousand years of erosion and vandalism. In 1378, the nose was pried off by an Islamic fundamentalist, a Sufi named Sa'im al-dahr, as reported by Muhammad al-Husayni Taqi al-Din al-Maqrizi (died AD 1442) (http://www.catchpenny.org/nose.html) However, some see Africoid features in what remains, pointing to, among other things, the image's pronounced facial prognathism, which remains clearly in evidence.[18] French scholar Constantin-François de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney visited Egypt between 1783 and 1785 and expressed astonishment upon seeing black Egyptians and what he recognized to be a "Negro" face of the Great Sphinx:

"...[Egyptians] all have a bloated face, puffed up eyes, flat nose, thick lips; in a word, the true face of the negro. I was tempted to attribute it to the climate, but when I visited the Sphinx, its appearance gave me the key to the riddle. On seeing that head, typically negro in all its features, I remembered the remarkable passage where Herodotus says: 'As for me, I judge the Colchians to be a colony of the Egyptians because, like them, they are black with woolly hair. ...'" In other words, the ancient Egyptians were true Negroes of the same type as all native-born Africans. That being so, we can see how their blood, mixed for several centuries with that of the Romans and Greeks, must have lost the intensity of its original color, while retaining nonetheless the imprint of its original mold. We can even state as a general principle that the face is a kind of monument able, in many cases, to attest or shed light on historical evidence on the origins of peoples.[19]

Upon visiting Egypt in 1849, French author Gustave Flaubert echoed de Volney's observations. In his travelog chronicling his trip, he wrote:

We stop before a Sphinx ; it fixes us with a terrifying stare. Its eyes still seem full of life; the left side is stained white by bird-droppings (the tip of the Pyramid of Khephren has the same long white stains); it exactly faces the rising sun, its head is grey, ears very large and protruding like a negro’s[20], its neck is eroded; from the front it is seen in its entirety thanks to great hollow dug in the sand; the fact that the nose is missing increases the flat, negroid effect. Besides, it was certainly Ethiopian; the lips are thick….[21]

Others also have remarked upon the Africoid face of the Sphinx, including W.E.B. Dubois [citation needed] in his work The Souls of Black Folk and Boston University professor and Sphinx scholar Robert M. Schoch, who has written that, "…the Sphinx has a distinctive 'African,' 'Nubian,' or 'Negroid' aspect…." [22]

Ethnographic murals

As can be seen from the adjacent painting, ancient Egyptians usually portrayed themselves differently from both the Nubians and the ethnically Semitic Middle-Easterners/North African Bedouins. The groups depicted in the painting are the Libyans, Nubians, Semites, and Egyptians, respectively from left to right.

There are numerous images in which Egyptians are contrasted with non-Egyptian peoples. Like other peoples throughout history, the Egyptians seem to have identified themselves as an ideal or norm of sorts among other populations. Further, there is evidence the ancient Egyptians thought in terms of national identity and ethnicity; the modern Western concept of "race" was alien to them. During the New Kingdom, Egyptian suzerainty extended to the north as far as the Hittite empire and into Nubia to the south. At this time, Egyptian sacred literature and imagery commented systematically on differences based on these two criteria. This is evident in Akhenaton's "Great Hymn to the Aten", in which it is said that the peoples of the world are differented by Aten: "Their tongues are separate in speech/And their natures as well;/ Their skins are distinguished./The countries of Syria and Nubia, the land of Egypt,/ You set every man in his place."

This differentiation of peoples is later refined in the Book of Gates, a sacred text that describes the passage of the soul though the underworld. This contains a description of the distinct peoples known to the Egyptians: Egyptians themselves, plus Asiatics, Nubians and Libyans. These peoples are illustrated in several tomb decorations, in which they are differentiated by skin-color and clothing. These depict Egyptians [23] ("Ret," or "men," often used as "ret na romé," meaning "we men above mankind"); Asiatics/Semites [24] ("AAMW" or "Namu,": "travelers" or "wanderers," often used as "namu sho," or "people who travel the sands," meaning the nomads or Bedu/Bedouin); Nubians [25] ("Nahasu," or "strangers"); and, finally, Libyans, [26] ("TMHHW", or Tamhu," a term for which several etymologies have been proposed). In all but one case, the Egyptians and Nubians are depicted differently. [27][28]

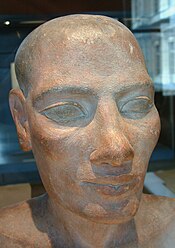

Cranial analysis and forensic reconstruction

As the 1993 study by the anthropologist C. Loring Brace suggested, the population of Predynastic Upper Egypt (based on 24 cranial measurements) fell roughly in between Northeastern Africa (Somalia, Nubia) and Neolithic Europe, whereas the population of Late Dynastic Lower Egypt was firmly in the Northern African/Neolithic European range (Brace, C. L. et al. 1993. Clines and Clusters Versus "Race": A Test in Ancient Egypt and the Case of a Death on the Nile. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology 36:1-31). Both were significantly different from the cranial measurements typically found in Sub-Saharan African populations and were more related to each other.[29]

Brace's study has faced some criticism, however. It had a greater number of samples from Europe and each sample represented a specific ethnic group whereas his samples from the "Sub-Saharan" region were very small and were not specific since each sample represented a country [citation needed]. Doing this exaggerated Europe's cranio-facial diversity to be greater than that of Sub-Sahara, even though Sub-Sahara is much more vast with thousands of ethnic groups. Even India which has hundreds of ethnic groups was represented by just one plot on his map. Also, the samples that Brace chose to represent Sub-Sahara consisted of those peoples who represent the stereotypical "true-negroid" look with broad features even though there are populations in Sub-Sahara that do not have such features[citation needed]. The result was that Egyptians as well as Nubians and even Somalians clustered closer to Europe because of certain similarities while Melanesians and Australian aborigines clustered closely to the Sub-Saharan sample because of certain similarities shared between them.

Of course, this criticism does not address the central issue of Brace's study, that Dynastic Egypt seems to have been biracial, at least judging by the skeletal remains, with its northern half being overwhelmingly Caucasoid, and its south having a closely related population that also grouped with other northeastern African ethnicities, such as Somalians and Nubians. To a significant degree this remains the case to this day.

The inaccuracy of cranial analysis

Although their methodology is seemingly objective, forensic anthropologists agree that attempts to apply criteria from craniofacial anthropometry, regularly yield counterintuitive results depending upon the weight given to each feature. Their application invariably results in finding some East and South Indians to have "Negroid" skulls and others to have "Caucasoid" skulls, for example, while Ethiopians, Somalis, and some Zulus have "Caucasoid" skulls, and the Khoisan of southwestern Africa have skulls distinct from other Black Africans.

In addition, about one-third of so-called "White" Americans have detectable African DNA markers or craniofacial traits that would forensically categorize them as "Negroid."[13] And about five percent of so-called "Black" Americans have no detectable "Negroid" traits at all, neither craniofacial nor in their DNA.[14] In short, given three Americans, one who self-identifies and is socially accepted as U.S. White, another one who self-identifies and is socially accepted as U.S. Black, and one who self-identifies and is socially accepted as U.S. Hispanic, and given that they have precisely the same Afro-European mix of ancestries (one "mulatto" grandparent), there is quite literally no objective test that will identify their U.S. endogamous group membership without an interview.[15] In practice, the application of such forensic criteria ultimately comes down to whether the skull "looks Negroid," "Caucasoid," or "Mongoloid" in the eye of each U.S. forensic practitioner.

Comparison to modern Africans

An interesting aspect of the recent reconstructions is their somewhat bucktoothed appearance.[citation needed] This form of facial projection, called an alveolar prognathism, with large incisors, is a trademark physical characteristic of many Sudanese, Somalis and other indigenous peoples of the region.

Scientific examination and analysis of skulls of royal Egyptian mummies across several dynasties confirm a predominance over time of sloping and dolichocephalic cranial structures and/or significant alveolar prognathisms and receding chins.[30] Further, these characteristics, common to "mesolithic Nubians" as well as modern-day Nubians,[31] were prominent features in royal mummies of the late 17th and 18th Dynasties: Queen consort Ahmose-Nefertari, Amenhotep I, Queen Meryetamon, Thutmose I, Thutmose II, Tjuyu (mother of Queen consort Tiye), and Queen Tiye.[32] According to cranial analysis by Harris and Wente, New Kingdom royal mummies showed strong Nubian affinities (like the 17th and 18th) or were at least Nubian-Levantine hybrids, as the 19th and 20th dynasties, with evidence of another potent Nubian infusion during the 21st dynasty. [33]

Edward F. Wente, Professor, The Oriental Institute and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations The University of Chicago notes that superimposed cephalometric tracing illustrated dissimilarity between Amenhotep III and Tutankhamun and between Amenhotep III and Thutmose IV. He further states:

Several mummies in particular Jim found to be quite anomalous in terms of their position within the genealogical sequence: Ahmose, Amenhotep II, Amenhotep III, and Seti II. Seti II is an interesting case, because he should belong to the Nineteenth Dynasty line, being the grandson of Ramesses II and son of Merenptah. Elliot Smith in his catalogue of the royal mummies had already noted in 1912 that Seti II does not at all resemble the orthognathous heavyjawed pharaohs of the Nineteenth Dynasty, but bears a striking resemblance to the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty. [34]

The authors of X-raying the Pharaohs, (1973) James E. Harris and Kent R. Weeks, wrote about Sekenenra Tao II of the Seventeenth Dynasty:

"His entire lower facial complex, in fact, is so different from other pharaohs that he could be fitted more easily into the series of Nubian and Old Kingdom Giza skulls than into that of later Egyptian kings. Various scholars in the past have proposed a Nubian--that is, non-Egyptian--origin for Seqenenra and his family, and his facial features suggest this might indeed be true. If it is, the history of the family that reputedly drove the Hyksos from Egypt, and the history of the Seventeenth Dynasty, stand in need of considerable re-examination". (James E. Harris, Kent R. Weeks, X-raying the Pharaohs, 1973, p. 135)

Reconstruction of King Tutankhamun likeness

1500 years after the founding of the first dynasty, Akhenaten and others of the 18th dynasty show facio-cranial characteristics which are in conformity with an Africoid phenotype [citation needed](see image of Queen Tiye above). Documentaries in 2002 and 2003 aired on the Discovery Channel in the United States provided strikingly Africoid images of both Tutankhamun[35] and Nefertiti [36] based on forensic reconstruction of mummified remains.

In the most recent attempt to put a face on the long-dead monarch, three separate teams of Egyptian, French and American investigators each produced a reconstruction of what they determined to be an accurate likeness of King Tutankhamun. The Egyptian and French teams knew the identity of the subject whose face they were reconstructing, the Egyptians working from CT scans of the skull itself, the French and American teams working from identical plastic reproductions. The American team, however, did not know the identity of the specimen.

According to a widely publicized press release dated May 10, 2005, Zahi Hawass of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), announced that "Based on this skull, the American and French teams both concluded that the subject was Caucasoid (the type of human typically found, for example, in North Africa, Europe and the Middle East)." [37]

In a telephone interview with the Washington Post, Susan Antón, a member of the American team, described the specimen as "somewhat equivocal" and, contrary to Hawass' pronouncement, did not use the term "Caucasoid", or any other racial term, to describe the skull of Pharaoh Tutankhamun. An image of the American reconstruction is available here [38].

"The decidedly masculine jaw was the giveaway, she said, although the rounded forehead, the sharp brow and the prominent eyes suggested a woman. Age was easy, she said. The third molars were in the process of coming in, something that happens between the ages of 18 and 20. Race was "the hardest call." The shape of the cranial cavity indicated an African, while the nose opening suggested narrow nostrils — a European characteristic. The skull was a North African." [39]

The French team's reconstruction has sparked considerable criticism. Afrocentrists criticize the French team's decision to select the skin tone by taking a color from the middle of the range of skin tones found in the population of Egypt today. [40] They claim that these features do not reflect the prevalent eye or skin color of either ancient dynastic Egypt or present-day Egyptians [citation needed]. They further argue that, since the two life-size guardian statues discovered protecting the main burial chamber show Tutankhamun as completely black to represent the king on his voyage through the darkness of the underworld, both the Egyptian and French teams, who knew the identity of the specimen, should have used those statues as a reference for a darker eye and skin pigmentation. These critics contend that a foreknowledge of their subject's identity and certain biases inclined the French to assign lighter eyes and skin and, as well, prompted acceptance of the selections by the Egyptian government. [citation needed]

Afrocentrists long have charged Hawass and the Egyptian government with mounting a campaign to "destroy" evidence [citation needed] of what Afrocentrists claim was a "black" civilization. The Egyptians themselves have in turn accused the usually West African descended Afrocentrists (often black Americans) of attempting to appropriate and bastardize Egyptian culture which has nothing to do with West Africa.[citation needed]

The highly pronounced expressions of the classic Nilotic phenotype[citation needed][41] exhibited by the skull of Tutankhamun and the complete absence of any physical incongruity which might indicate the presence of another ethnic bloodline—such as a flattening or rounding of the skull (so dolichocephalic in the case of King Tutankhamun,[42] it was theorized at one time to be a genetic deformity, a speculation later discounted),[43] which is evident in some royal mummies across the millennia— are strong indicators that the dark brown pigments used in most of the contemporaneous renderings of the young king[44] likely closely approximated the monarch's natural skin tone [citation needed].

In popular culture

With the excavation of the tomb of Pharaoh Tutankhamun of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt in 1922, a wave of what has been called "Egyptomania" swept the Western world, triggering renderings of ancient Egyptians in consumer goods, decorative arts and in film. While some of these images were more Negroid or Semitic in appearance, the vast majority portrayed Egyptians as Caucasoid and fair-skinned. In the American cinema, white actors predominated in roles portraying ancient Egyptians and their pharaohs, and when black actors were cast, they usually appeared as servants or Nubian slaves.

Notes

The pale-white renderings of most royal women is thought to have nothing to do with their actual skin color, as these figures represent their femininity as a lighter skin tone. The association of "yellow khenet was symbolic of all that is eternal and imperishable in the Egyptian religion". -- Marie Parsons [45] [46]

The jet-black renderings of Tutankhamun is thought to have nothing to do with his actual skin color, as these figures represent his voyage through the pitch darkness of the underworld -- a significant afterlife ritual.[47]. "[The burial] chamber was guarded by two black sentry-statues that represent the royal ka (soul) and symbolize the hope of rebirth -- the qualities of Osiris, who was reborn after he died."[48].

References

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, L.L., P. Menozzi, and A. Piazza. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Compared populations from throughout the world using extensive genetic data. The North African populations grouped with West Eurasian (European, Middle East) populations rather than sub-Saharan Africans.

- ^ Hammer, M. et al. 1997. The geographic distribution of human Y chromosome variation. Genetics 145(3):787-805. Used seven different methods to compute population trees of world populations, using Y-chromosome data. All seven methods grouped the Egyptians with the non-African populations rather than with the sub-Saharan Africans. Egyptians' genetic profile resembles that of South Europeans more than the other regional groups in the study.

- ^ Bosch, E. et al. 1997. Population history of north Africa: evidence from classical genetic markers. Human Biology. 69(3):295-311. Using classical genetic markers, calculated Egyptians to be genetically very close to Mediterranean Asians and Europeans.

- ^ Kivisild T; Reidla M; Metspalu E; Rosa A; Brehm A; et al. Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: Tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears. 2004 American Journal of Human Genetics 75 (5): 752-770. Determined there is a close genetic relationship between Ethiopians (a Sub-Saharan African country) and Yemen, as well as pointing out genetic affinities with Egypt.

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, L.L., P. Menozzi, and A. Piazza. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Compared populations from throughout the world using extensive genetic data. The North African populations grouped with West Eurasian (European, Middle East) populations rather than sub-Saharan Africans.

- ^ Hammer, M. et al. 1997. The geographic distribution of human Y chromosome variation. Genetics 145(3):787-805. Used seven different methods to compute population trees of world populations, using Y-chromosome data. All seven methods grouped the Egyptians with the non-African populations rather than with the sub-Saharan Africans. Egyptians' genetic profile resembles that of South Europeans more than the other regional groups in the study.

- ^ Bosch, E. et al. 1997. Population history of north Africa: evidence from classical genetic markers. Human Biology. 69(3):295-311. Using classical genetic markers, calculated Egyptians to be genetically very close to Mediterranean Asians and Europeans.

- ^ Kivisild T; Reidla M; Metspalu E; Rosa A; Brehm A; et al. Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: Tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears. 2004 American Journal of Human Genetics 75 (5): 752-770. Determined there is a close genetic relationship between Ethiopians (a Sub-Saharan African country) and Yemen, as well as pointing out genetic affinities with Egypt.

- ^ Cavalli-Sforza, L.L., P. Menozzi, and A. Piazza. 1994. The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Compared populations from throughout the world using extensive genetic data. The North African populations grouped with West Eurasian (European, Middle East) populations rather than sub-Saharan Africans.

- ^ Hammer, M. et al. 1997. The geographic distribution of human Y chromosome variation. Genetics 145(3):787-805. Used seven different methods to compute population trees of world populations, using Y-chromosome data. All seven methods grouped the Egyptians with the non-African populations rather than with the sub-Saharan Africans. Egyptians' genetic profile resembles that of South Europeans more than the other regional groups in the study.

- ^ Bosch, E. et al. 1997. Population history of north Africa: evidence from classical genetic markers. Human Biology. 69(3):295-311. Using classical genetic markers, calculated Egyptians to be genetically very close to Mediterranean Asians and Europeans.

- ^ Kivisild T; Reidla M; Metspalu E; Rosa A; Brehm A; et al. Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: Tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears. 2004 American Journal of Human Genetics 75 (5): 752-770. Determined there is a close genetic relationship between Ethiopians and Yemen, as well as pointing out genetic affinities with Egypt.

- ^ Heather E. Collins-Schramm and others, "Markers that Discriminate Between European and African Ancestry Show Limited Variation Within Africa," Human Genetics 111 (2002): 566-9; Mark D. Shriver and others, "Skin Pigmentation, Biogeographical Ancestry, and Admixture Mapping," Human Genetics 112 (2003): 387-99.

- ^ E.J. Parra and others, "Ancestral Proportions and Admixture Dynamics in Geographically Defined African Americans Living in South Carolina," American Journal of Physical Anthropology 114 (2001): 18-29, Figure 1.

- ^ Carol Channing, Just Lucky I Guess: A Memoir of Sorts (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2002); Gregory Howard Williams, Life on the Color Line: The True Story of a White Boy who Discovered he was Black (New York: Dutton, 1995)

Bibliography

- Noguera, Anthony (1976). How African Was Egypt?: A Comparative Study of Ancient Egyptian and Black African Cultures. Illustrations by Joelle Noguera. New York: Vantage Press.