Illinois

Illinois | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Illinois Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | December 3, 1818 (21st) |

| Capital | Springfield |

| Largest city | Chicago |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Chicago metropolitan area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Pat Quinn (D) |

| • Lieutenant governor | Sheila Simon (D) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Dick Durbin (D) Mark Kirk (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 12 Democrats, 6 Republicans (list) |

| Population | |

• Total | 12,882,135 (2,013 est)[1] |

| • Density | 232/sq mi (89.4/km2) |

| • Median household income | $54,124 |

| • Income rank | 17 |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English[2] |

| • Spoken language | English (80.8%) Spanish (14.9%) Other (5.1%)[3] American 1923-1969 |

| Latitude | 36° 58′ N to 42° 30′ N |

| Longitude | 87° 30′ W to 91° 31′ W |

Illinois (/ˌɪl[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈnɔɪ/ IL-i-NOY) is a state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 5th most populous and 25th most extensive state, and is often noted as a microcosm of the entire country.[7] With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal, timber, and petroleum in the south, Illinois has a diverse economic base and is a major transportation hub. The Port of Chicago connects the state to other global ports from the Great Lakes, via the Saint Lawrence Seaway, to the Atlantic Ocean; as well as the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River, via the Illinois River. For decades, O'Hare International Airport has been ranked as one of the world's busiest airports. Illinois has long had a reputation as a bellwether both in social and cultural terms[7] and politics.

Although today the state's largest population center is around Chicago in the northern part of the state, the state's European population grew first in the west, with French Canadians who settled along the Mississippi River. After the American Revolutionary War established the United States, American settlers began arriving from Kentucky in the 1810s via the Ohio River, and the population grew from south to north. In 1818, Illinois achieved statehood. After construction of the Erie Canal increased traffic and trade through the Great Lakes, Chicago was founded in the 1830s on the banks of the Chicago River, at one of the few natural harbors on southern Lake Michigan.[8] John Deere's invention of the self-scouring steel plow turned Illinois' rich prairie into some of the world's most productive and valuable farmlands, attracting immigrant farmers from Germany and Sweden. Railroads carried immigrants to new homes, as well as being used to ship their commodity crops out to markets.

By 1900, the growth of industrial jobs in the northern cities and coal mining in the central and southern areas attracted immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. Illinois was an important manufacturing center during both world wars. The Great Migration from the South established a large community of African Americans in Chicago, who created the city's famous jazz and blues cultures.[9][10]

Three U.S. presidents have been elected while living in Illinois: Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Barack Obama. Additionally, Ronald Reagan, whose political career was based in California, was the only US President born and raised in Illinois. Today, Illinois honors Lincoln with its official state slogan, Land of Lincoln, which has been displayed on its license plates since 1954.[11][12] The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum is located in the state capital of Springfield.

Name

"Illinois" is the modern spelling for the early French missionaries and explorers' name for the Illinois natives, a name that was spelled in many different ways in the early records.[13]

American scholars previously thought the name "Illinois" meant "man" or "men" in the Miami-Illinois language, with the original iliniwek transformed via French into Illinois.[14][15] This etymology is not supported by the Illinois language, as the word for 'man' is ireniwa and plural 'men' is ireniwaki. The name Illiniwek has also been said to mean "tribe of superior men",[16] which is a false etymology. The name "Illinois" derives from the Miami-Illinois verb irenwe·wa "he speaks the regular way". This was taken into the Ojibwe language, perhaps in the Ottawa dialect, and modified into ilinwe· (pluralized as ilinwe·k). The French borrowed these forms, changing the /we/ ending to spell it as -ois, a transliteration for its pronunciation in French of that time. The current spelling form, Illinois, began to appear in the early 1670s, when French colonists had settled in the western area. The Illinois' name for themselves, as attested in all three of the French missionary-period dictionaries of Illinois, was Inoka, of unknown meaning and unrelated to the other terms.[17][18]

History

Pre-European

American Indians of successive cultures lived along the waterways of the Illinois area for thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. The Koster Site has been excavated and demonstrates 7,000 years of continuous habitation. Cahokia, the largest regional chiefdom and urban center of the Pre-Columbian Mississippian culture, was located near present-day Collinsville, Illinois. They built an urban complex of more than 100 platform and burial mounds, a 50 acres (20 ha) plaza larger than 35 football fields,[19] and a woodhenge of sacred cedar, all in a planned design expressing the culture's cosmology. Monks Mound, the center of the site, is the largest precolumbian structure north of the Valley of Mexico. It is 100 feet (30 m) high, 951 feet (290 m) long, 836 feet (255 m) wide and covers 13.8 acres (5.6 ha).[20] It contains about 814,000 cubic yards (622,000 m3) of earth.[21] It was topped by a structure thought to have measured about 105 feet (32 m) in length and 48 feet (15 m) in width, covered an area 5,000 square feet (460 m2), and been as much as 50 feet (15 m) high, making its peak 150 feet (46 m) above the level of the plaza. The civilization vanished in the 15th century for unknown reasons, but historians and archeologists have speculated that the people depleted the area of resources. Many indigenous tribes engaged in constant warfare. According to Suzanne Austin Alchon, "At one site in the central Illinois River valley, one-third of all adults died as a result of violent injuries."[22]

The next major power in the region was the Illinois Confederation or Illini, a political alliance.[23] Gradually, members of the Algonquian-speaking Potawatomi, Miami, Sauk, and other tribes came into the area from the east and north around the Great Lakes.[24] In the American Revolution, the Illinois and Potawatomi supported the Patriot colonists' cause.

European exploration

French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored the Illinois River in 1673. In 1680, other French explorers constructed a fort at the site of present day Peoria, and in 1682, a fort atop Starved Rock in today's Starved Rock State Park. French Canadians came south to settle particularly along the Mississippi River, and Illinois was part of the French empire of La Louisiane until 1763, when it passed to the British with their defeat of France in the Seven Years' War. The small French settlements continued, although many French migrated west to Ste. Genevieve and St. Louis, Missouri to evade British rule.[26]

A few British soldiers were posted in Illinois, but few British or American settlers moved there, as the Crown made it part of the territory reserved for Indians west of the Appalachians. In 1778, George Rogers Clark claimed Illinois County for Virginia. In a compromise, Virginia ceded the area to the new United States in 1783 and it became part of the Northwest Territory, to be administered by the federal government and later organized as states.[26]

19th century

The Illinois-Wabash Company was an early claimant to much of Illinois. The Illinois Territory was created on February 3, 1809, with its capital at Kaskaskia, an early French settlement.

During the discussions leading up to Illinois' admission to the Union, the proposed northern boundary of the state was moved twice.[27] The original provisions of the Northwest Ordinance had specified a boundary that would have been tangent to the southern tip of Lake Michigan. Such a boundary would have left Illinois with no shoreline on Lake Michigan at all. However, as Indiana had successfully been granted a 10-mile northern extension of its boundary to provide it with a usable lakefront, the original bill for Illinois statehood, submitted to Congress on January 23, 1818, stipulated a northern border at the same latitude as Indiana's, which is defined as 10 miles (16 km) north of the southernmost extremity of Lake Michigan. But the Illinois delegate, Nathaniel Pope, wanted more. Pope lobbied to have the boundary moved further north, and the final bill passed by Congress did just that; it included an amendment to shift the border to 42° 30' north, which is approximately 51 miles (82 km) north of the Indiana northern border. This shift added 8,500 square miles (22,000 km2) to the state, including the lead mining region near Galena. More importantly, it added nearly 50 miles of Lake Michigan shoreline and the Chicago River. Pope and others envisioned a canal which would connect the Chicago and Illinois rivers, and thus, connect the Great Lakes to the Mississippi.

In 1818, Illinois became the 21st U.S. state. The capital remained at Kaskaskia, headquartered in a small building rented by the state. In 1819, Vandalia became the capital, and over the next 18 years, three separate buildings were built to serve successively as the capitol building. In 1837, the state legislators representing Sangamon County, under the leadership of state representative Abraham Lincoln, succeeded in having the capital moved to Springfield,[28] where a fifth capitol building was constructed. A sixth capitol building was erected in 1867, which continues to serve as the Illinois capitol today.

Though it was ostensibly a "free state", there was slavery in Illinois. The ethnic French had owned black slaves as late as the 1820s, and American settlers had already brought slaves into the area from Kentucky. Slavery was nominally banned by the Northwest Ordinance, but that was not enforced for those already holding slaves. When Illinois became a sovereign state in 1818, the Ordinance no longer applied, and about 900 slaves were held in the state. As the southern part of the state, later known as "Egypt"or "Little Egypt",[29][30] was largely settled by migrants from the South, the section was hostile to free blacks. Settlers were allowed to bring slaves with them for labor but, in 1822, state residents voted against making slavery legal. Still, most residents opposed allowing free blacks as permanent residents. Some settlers brought in slaves seasonally or as house servants.[31] The Illinois Constitution of 1848 was written with a provision for exclusionary laws to be passed. In 1853, John A. Logan helped pass a law to prohibit all African Americans, including freedmen, from settling in the state.[32]

In 1832, the Black Hawk War was fought in Illinois and current-day Wisconsin between the United States and the Sauk, Fox (Meskwaki) and Kickapoo Indian tribes. It represents the end of Indian resistance to white settlement in the Chicago region.[33] The Indians had been forced to leave their homes and move to Iowa in 1831; when they attempted to return, they were attacked and eventually defeated by U.S. militia. The survivors were forced back to Iowa.[34]

The winter of 1830–1831 is called the "Winter of the Deep Snow"; a sudden, deep snowfall blanketed the state, making travel impossible for the rest of the winter, and many travelers perished. Several severe winters followed, including the "Winter of the Sudden Freeze". On December 20, 1836, a fast-moving cold front passed through, freezing puddles in minutes and killing many travelers who could not reach shelter. The adverse weather resulted in crop failures in the northern part of the state. The southern part of the state shipped food north and this may have contributed to its name: "Little Egypt", after the Biblical story of Joseph in Egypt supplying grain to his brothers.[35]

By 1839, the Mormons had founded a utopian city called Nauvoo. Located in Hancock County along the Mississippi River, Nauvoo flourished and soon rivaled Chicago for the position of the state's largest city. But in 1844, the Mormon leader Joseph Smith was murdered in the Carthage Jail, about 30 miles away from Nauvoo. Soon afterward, the Mormons' new leadership led the group out of Illinois in a mass exodus to present-day Utah; after close to six years of rapid development, Nauvoo rapidly declined afterward. [citation needed]

Chicago gained prominence as a Great Lakes port and then as an Illinois and Michigan Canal port after 1848, and as a rail hub soon afterward. By 1857, Chicago was Illinois' largest city.[26] With the tremendous growth of mines and factories in the state in the 19th century, Illinois was the ground for the formation of labor unions in the United States. The Pullman Strike and Haymarket Riot, in particular, greatly influenced the development of the American labor movement. From Sunday, October 8, 1871, until Tuesday, October 10, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire burned in downtown Chicago, destroying 4 square miles (10 km2).[36]

In 1847, after lobbying by Dorothea L. Dix, Illinois became one of the first states to establish a system of state-supported treatment of mental illness and disabilities, replacing local almshouses.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, Illinois ranked fourth in men who served (more than 250,000) in the Union Army, a figure surpassed by only New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. Beginning with President Abraham Lincoln's first call for troops and continuing throughout the war, Illinois mustered 150 infantry regiments, which were numbered from the 7th to the 156th regiments. Seventeen cavalry regiments were also gathered, as well as two light artillery regiments.[37] The town of Cairo, at the southern tip of the state at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, served as a strategically important supply base and training center for the Union army. For several months, both General Grant and Admiral Foote had headquarters in Cairo.

20th century

At the turn of the 20th century, Illinois had a population of nearly 5 million. Many people from other parts of the country were attracted to the state by employment caused by the then-expanding industrial base. Whites were 98% of the state's population.[38] Bolstered by continued immigration from southern and eastern Europe, and by the African-American Great Migration from the South, Illinois grew and emerged as one of the most important states in the union. By the end of the century, the population had reached 12.4 million.

The Century of Progress World's Fair was held at Chicago in 1933. Oil strikes in Marion County and Crawford County lead to a boom in 1937, and, by 1939, Illinois ranked fourth in U.S. oil production. Illinois manufactured 6.1 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking seventh among the 48 states.[39] Chicago became an ocean port with the opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway in 1959. The seaway and the Illinois Waterway connected Chicago to both the Mississippi River and the Atlantic Ocean. In 1960, Ray Kroc opened the first McDonald's franchise in Des Plaines (which still exists today as a museum, with a working McDonald's across the street).

Illinois had a prominent role in the emergence of the nuclear age. As part of the Manhattan Project, in 1942 the University of Chicago conducted the first sustained nuclear chain reaction. In 1957, Argonne National Laboratory, near Chicago, activated the first experimental nuclear power generating system in the United States. By 1960, the first privately financed nuclear plant in United States, Dresden 1, was dedicated near Morris. In 1967, Fermilab, a national nuclear research facility near Batavia, opened a particle accelerator, which was the world's largest for over 40 years. And, with eleven plants currently operating, Illinois leads all states in the amount of electricity generated from nuclear power.[40][41]

In 1961, Illinois became the first state in the nation to adopt the recommendation of the American Law Institute and pass a comprehensive criminal code revision that repealed the law against sodomy. The code also abrogated common law crimes and established an age of consent of 18.[42] The state's fourth constitution was adopted in 1970, replacing the 1870 document.

The first Farm Aid concert was held in Champaign to benefit American farmers, in 1985. The worst upper Mississippi River flood of the century, the Great Flood of 1993, inundated many towns and thousands of acres of farmland.[26]

Geography

Illinois is located in the Midwest Region of the United States and is one of the nine states and Canadian Province of Ontario in the bi-national Great Lakes region of North America.

Boundaries

Illinois' eastern border with Indiana consists of a north-south line at 87° 31′ 30″ west longitude in Lake Michigan at the north, to the Wabash River in the south above Post Vincennes. The Wabash River continues as the eastern/southeastern border with Indiana until the Wabash enters the Ohio River. This marks the beginning of Illinois' southern border with Kentucky, which runs along the northern shoreline of the Ohio River.[43] Most of the western border with Missouri and Iowa is the Mississippi River; Kaskaskia is an exclave of Illinois, lying west of the Mississippi and reachable only from Missouri. The states northern border with Wisconsin is fixed at 42° 30' north latitude. The northeastern border of Illinois lies in Lake Michigan, within which Illinois shares a water boundary with the state of Michigan, as well as Wisconsin and Indiana.[24]

Topography

Though Illinois lies entirely in the Interior Plains, it does have some minor variation in its elevation. In extreme northwestern Illinois, the Driftless Area, a region of unglaciated and therefore higher and more rugged topography, occupies a small part of the state. Charles Mound, located in this region, has the state's highest elevation above sea level at 1,235 feet (376 m). Other highlands include the Shawnee Hills in the south, and there is varying topography along its rivers; the Illinois River bisects the state northeast to southwest. The floodplain on the Mississippi River from Alton to the Kaskaskia River is known as the American Bottom.

Divisions

Illinois has three major geographical divisions. Northern Illinois is dominated by Chicagoland, which is the city of Chicago and its suburbs, and the adjoining exurban area into which the metropolis is expanding. As defined by the federal government, the Chicago metro area includes several counties in Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, and has a population of over 9.8 million people. Chicago itself is a cosmopolitan city, densely populated, industrialized, and the transportation hub of the nation, and settled by a wide variety of ethnic groups. The city of Rockford, Illinois' third largest city and center of the state's fourth largest metropolitan area, sits along Interstates 39 and 90 some 75 miles (121 km) northwest of Chicago. The Quad Cities region, located along the Mississippi River in northern Illinois, had a population of 381,342 in 2011.

The midsection of Illinois is a second major division, called Central Illinois. It is an area of mostly prairie and known as the Heart of Illinois. It is characterized by small towns and medium-small cities. The western section (west of the Illinois River) was originally part of the Military Tract of 1812 and forms the conspicuous western bulge of the state. Agriculture, particularly corn and soybeans, as well as educational institutions and manufacturing centers, figure prominently in Central Illinois. Cities include Peoria, Springfield, the state capital; Quincy; Decatur; Bloomington-Normal; and Champaign-Urbana.[24]

The third division is Southern Illinois, comprising the area south of U.S. Route 50, including Little Egypt, near the juncture of the Mississippi River and Ohio River. Southern Illinois is the site of the ancient city of Cahokia, as well as the site of the first state capital at Kaskaskia, which today is separated from the rest of the state by the Mississippi River.[24][44] This region has a somewhat warmer winter climate, different variety of crops (including some cotton farming in the past), more rugged topography (due to the area remaining unglaciated during the Illinoian Stage, unlike most of the rest of the state), as well as small-scale oil deposits and coal mining. The Illinois suburbs of St. Louis, such as East St. Louis are located in this region and collectively they are known as the Metro-East. The other somewhat significant concentration of population in Southern Illinois is the Carbondale-Marion-Herrin, Illinois Combined Statistical Area centered on Carbondale and Marion, a two-county area that is home to 123,272 residents.[24] A portion of southeastern Illinois is part of the extended Evansville, Indiana Metro Area, locally referred to as the Tri-State with Indiana and Kentucky. Seven Illinois counties are in the area.

In addition to these three, largely latitudinally defined divisions, all of the region outside of the Chicago Metropolitan area is often called "downstate" Illinois. This term is flexible, but is generally meant to mean everything outside the Chicago-area. Thus, some cities in Northern Illinois, such as DeKalb, which is west of Chicago, and Rockford—which is actually north of Chicago—are considered to be "downstate".

Climate

Illinois has a climate that varies widely throughout the year. Because of its nearly 400-mile distance between its northernmost and southernmost extremes, as well as its mid-continental situation, most of Illinois has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa), with hot, humid summers and cold winters. The southernmost part of the state, from about Carbondale southward, borders on a humid subtropical climate (Koppen Cfa), with more moderate winters. Average yearly precipitation for Illinois varies from just over 48 inches (1,219 mm) at the southern tip to around 35 inches (889 mm) in the northern portion of the state. Normal annual snowfall exceeds 38 inches (965 mm) in the Chicago area, while the southern portion of the state normally receives less than 14 inches (356 mm).[45] The all-time high temperature was 117 °F (47 °C), recorded on July 14, 1954, at East St. Louis, while the all time low temperature was −36 °F (−38 °C), recorded on January 5, 1999, at Congerville.[46] A temperature of -37 °F (-39 °C), was recorded on January 15, 2009, at Rochelle.[47]

Illinois averages around 51 days of thunderstorm activity a year, which ranks somewhat above average in the number of thunderstorm days for the United States. Illinois is vulnerable to tornadoes with an average of 35 occurring annually, which puts much of the state at around five tornadoes per 10,000 square miles (30,000 km2) annually.[48] While tornadoes are no more powerful in Illinois than other states, the nation's deadliest tornadoes on record have occurred largely in Illinois because it is the most populous state in Tornado Alley. The Tri-State Tornado of 1925 killed 695 people in three states; 613 of the victims died in Illinois.[49] Other significant high-casualty tornadoes included the 1896 St. Louis – East St. Louis tornado which killed 111 people in East St. Louis and a May 1917 tornado that killed 101 people in Charleston and Mattoon. Modern developments in storm forecasting and tracking have caused death tolls from tornadoes to decline dramatically, with the 1967 Belvidere – Oak Lawn tornado outbreak (58 fatalities) and 1990 Plainfield tornado (29 fatalities) standing out as exceptions. On November 18, 2013, tornadoes touched down and ripped through Washington, Illinois. There were 7 fatalities.

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cairo[50] | 43/25 | 48/29 | 59/37 | 70/46 | 78/57 | 86/67 | 90/71 | 88/69 | 81/61 | 71/49 | 57/39 | 46/30 |

| Chicago[51] | 31/18 | 36/22 | 47/31 | 59/42 | 70/52 | 81/61 | 85/65 | 83/65 | 75/57 | 64/45 | 48/34 | 36/22 |

| Edwardsville[52] | 36/19 | 42/24 | 52/34 | 64/45 | 75/55 | 84/64 | 89/69 | 86/66 | 79/58 | 68/46 | 53/35 | 41/25 |

| Moline[53] | 30/12 | 36/18 | 48/29 | 62/39 | 73/50 | 83/60 | 86/64 | 84/62 | 76/53 | 64/42 | 48/30 | 34/18 |

| Peoria[54] | 31/14 | 37/20 | 49/30 | 62/40 | 73/51 | 82/60 | 86/65 | 84/63 | 77/54 | 64/42 | 49/31 | 36/20 |

| Rockford[55] | 27/11 | 33/16 | 46/27 | 59/37 | 71/48 | 80/58 | 83/63 | 81/61 | 74/52 | 62/40 | 46/29 | 32/17 |

| Springfield[56] | 33/17 | 39/22 | 51/32 | 63/42 | 74/53 | 83/62 | 86/66 | 84/64 | 78/55 | 67/44 | 51/34 | 38/23 |

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 2,458 | — | |

| 1810 | 12,282 | 399.7% | |

| 1820 | 55,211 | 349.5% | |

| 1830 | 157,445 | 185.2% | |

| 1840 | 476,183 | 202.4% | |

| 1850 | 851,470 | 78.8% | |

| 1860 | 1,711,951 | 101.1% | |

| 1870 | 2,539,891 | 48.4% | |

| 1880 | 3,077,871 | 21.2% | |

| 1890 | 3,826,352 | 24.3% | |

| 1900 | 4,821,550 | 26.0% | |

| 1910 | 5,638,591 | 16.9% | |

| 1920 | 6,485,280 | 15.0% | |

| 1930 | 7,630,654 | 17.7% | |

| 1940 | 7,897,241 | 3.5% | |

| 1950 | 8,712,176 | 10.3% | |

| 1960 | 10,081,158 | 15.7% | |

| 1970 | 11,113,976 | 10.2% | |

| 1980 | 11,426,518 | 2.8% | |

| 1990 | 11,430,602 | 0.0% | |

| 2000 | 12,419,293 | 8.6% | |

| 2010 | 12,830,632 | 3.3% | |

| 2013 (est.) | 12,882,135 | 0.4% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[57] 2013 Estimate[58] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Illinois was 12,882,135 on July 1, 2013, a 0.3% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[1] Illinois is the most populous state in the Midwest region. Chicago, the third most populous city in the United States, is the center of the Chicago metropolitan area. Chicagoland, as this area is known locally, comprises only 8% of the land area of the state, but contains 65% of the state's residents.

According to the 2010 Census, the racial composition of the state was:

- 71.5% White American (63.7% non-Hispanic white, 7.8% White Hispanic)

- 14.5% Black or African American

- 0.3% American Indian and Alaska Native

- 4.6% Asian American

- 2.3% Multiracial American

- 6.8% some other race

In the same year 15.8% of the total population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (they may be of any race).[59]

| Racial composition | 1990[60] | 2000[61] | 2010[62] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 78.3% | 73.5% | 71.5% |

| Black | 14.8% | 15.1% | 14.5% |

| Asian | 2.5% | 3.4% | 4.6% |

| Native | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

- | - | - |

| Other race | 4.2% | 5.8% | 6.7% |

| Two or more races | - | 1.9% | 2.3% |

The state's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic white, has declined from 83.5% in 1970 to 63.3% in 2011.[38][63] As of 2011, 49.4% of Illinois's population younger than age 1 were minorities(note: children born to white Hispanics are counted as minority group).[64]

At the 2007 estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau, there were 1,768,518 foreign-born inhabitants of the state or 13.8% of the population, with 48.4% from Latin America, 24.6% from Asia, 22.8% from Europe, 2.9% from Africa, 1.2% from Northern America and 0.2% from Oceania. Of the foreign-born population, 43.7% were naturalized U.S. citizens and 56.3% were not U.S. citizens.[65] In 2007, 6.9% of Illinois' population was reported as being under age 5, 24.9% under age 18 and 12.1% were age 65 and over. Females made up approximately 50.7% of the population.[66]

According to the 2007 estimates, 21.1% of the population had German ancestry, 13.3% had Irish ancestry, 8% had British ancestry, 7.9% had Polish ancestry, 6.4% had Italian ancestry, 4.6% listed themselves as American, 2.4% had Swedish ancestry, 2.2% had French ancestry, other than Basque, 1.6% had Dutch ancestry, and 1.4% had Norwegian ancestry.[65]

Chicago, along the shores of Lake Michigan, is the nation's third largest city. In 2000, 23.3% of Illinois' population lived in the city of Chicago, 43.3% in Cook County, and 65.6% in the counties of the Chicago metropolitan area: Will, DuPage, Kane, Lake, and McHenry counties, as well as Cook County. The remaining population lives in the smaller cities and rural areas that dot the state's plains. As of 2000, the state's center of population was at 41°16′42″N 88°22′49″W / 41.278216°N 88.380238°W, located in Grundy County, northeast of the village of Mazon.[24][26][44][67]

Urban areas

Chicago is the largest city in the state and the third most populous city in the United States, with its 2010 population of 2,695,598. The U.S. Census Bureau currently lists seven other cities with populations of over 100,000 within Illinois. Based upon the Census Bureau's official 2010 population:[68] Aurora, a Chicago satellite town which eclipsed Rockford for the title of second most populous city in Illinois; its 2010 population was 197,899. Rockford, at 152,871, is the third largest city in the state, and is the largest city in the state not located within the Chicago suburbs. Joliet, located in metropolitan Chicago, is the fourth largest city in the state, with a population of 147,433. Naperville, a suburb of Chicago, is fifth with 141,853. Naperville and Aurora share a boundary along Illinois Route 59. Springfield, the state's capital, comes in as sixth most populous with 117,352 residents. Peoria, which decades ago was the second-most populous city in the state, is seventh with 115,007. The eighth largest and final city in the 100,000 club is Elgin, a northwest suburb of Chicago, with a 2010 population of 108,188.

The most populated city in the state south of Springfield is Belleville, with 44,478 people at the 2010 census. It is located in the Illinois portion of Greater St. Louis (often called the Metro-East area), which has a rapidly growing population of over 700,000 people.

Other major urban areas include the Champaign-Urbana Metropolitan Area, which has a combined population of almost 230,000 people, the Illinois portion of the Quad Cities area with about 215,000 people, and the Bloomington-Normal area with a combined population of over 165,000.

Most populous places

Template:Largest cities of Illinois

Languages

The official language of Illinois is English. Nearly 80% of the population speak English natively, and most of the rest speak it fluently as a second language.[69] A number of dialects of American English are spoken, ranging from Inland Northern American English around Chicago, to Southern American English in the far south. Illinois has speakers of many other immigrant languages, of which Spanish is by far the most widespread. Illinois's indigenous languages disappeared when the Indian population was deported under the policy of Indian Removal.

In 1923, Republican congressman, Washington J. McCormick, proposed that the official language of the United States should be changed to American, instead of English. This was the first time that congress had ever considered changing the national language, eventually the bill failed, but was later adopted in the state of Illinois after State Senator Frank Ryan of Illinois proposed a bill to make American the official language of the state of Illinois, which was officially adopted by the state in 1923. It wasn't until Chicago mayor Bill Thompson was specifically blamed by the Democratic sponsor for the 1923 revision changing the official language, which was then revised changing “American” back to “English” as the official language of Illinois, in 1969, this was due to the fact that many residents continued to speak and teach English.

Religion

Roman Catholics constitute the single largest religious denomination in Illinois; they are heavily concentrated in and around Chicago, and account for nearly 30% of the state's population.[75] However, taken together as a group, the various Protestant denominations comprise a greater percentage of the state's population than do Catholics. In 2010 Catholics in Illinois numbered 3,648,907. The largest Protestant denominations were the United Methodist Church with 314,461, and the Southern Baptist Convention, with 283,519 members. Muslims constituted the largest non-Christian group with 359,264 adherents.[76] Chicago and its suburbs are also home to a large and growing population of Hindus, Muslims, Baha'is and Buddists.[77]

Illinois played an important role in the early Latter Day Saint movement, with Nauvoo, Illinois, becoming a gathering place for Mormons in the early 1840s. Nauvoo was the location of the succession crisis, which led to the separation of the Mormon movement into several Latter Day Saint sects. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the largest of the sects to emerge from the Mormon schism, has over 55,000 adherents in Illinois today.[78] The largest and oldest surviving Bahá'í House of Worship in the world is located in Wilmette, Illinois.

Economy

The dollar gross state product for Illinois was estimated to be US$652 billion in 2010.[79] The state's 2010 per capita gross state product was estimated to be US$45,302,[79] the state's per capita personal income was estimated to be US$41,411 in 2009,[80] while the state's taxpayer burden in 2011 was estimated at US$38,500 per taxpayer.[81]

As of March 2010[update], the state's unemployment rate was 11.5%,[82] which fell to 9.9% by August 2011.[83]

Taxes

Illinois' state income tax is calculated by multiplying net income by a flat rate. In 1990, that rate was set at 3%, but in 2010, the General Assembly voted in a temporary increase in the rate to 5%; the new rate went into effect on January 1, 2011, and is scheduled to return to 3% after four years.[84][85] There are two rates for state sales tax: 6.25% for general merchandise and 1% for qualifying food, drugs, and medical appliances.[86] The property tax is a major source of tax revenue for local government taxing districts. The property tax is a local — not state — tax, imposed by local government taxing districts, which include counties, townships, municipalities, school districts, and special taxation districts. The property tax in Illinois is imposed only on real property.[24][26][44]

Agriculture

Illinois' major agricultural outputs are corn, soybeans, hogs, cattle, dairy products, and wheat. In most years, Illinois is either the first or second state for the highest production of soybeans, with a harvest of 427.7 million bushels (11.64 million metric tons) in 2008, after Iowa's production of 444.82 million bushels (12.11 million metric tons).[87] Illinois ranks second in U.S. corn production with more than 1.5 billion bushels produced annually.[88] With a production capacity of 1.5 billion gallons per year, Illinois is a top producer of ethanol; ranking third in the United States in 2011.[89] Illinois is a leader in food manufacturing and meat processing.[90] Although Chicago may no longer be "Hog Butcher for the World," the Chicago area remains a global center for food manufacture and meat processing,[90] with many plants, processing houses, and distribution facilities concentrated in the area of the former Union Stock Yards.[91] Illinois also produces wine, and the state is home to two American viticultural areas. In the area of The Meeting of the Great Rivers Scenic Byway, peach and apple are grown. The German immigrants from agricultural backgrounds who settled in Illinois in mid- to late 19th century are the in part responsible for the profusion of fruit orchards in that area of Illinois.[92] Illinois' universities are actively researching alternative agricultural products as alternative crops.

Manufacturing

Illinois is one of the nation's manufacturing leaders, boasting annual value added productivity by manufacturing of over $107 billion in 2006. As of 2011, Illinois is ranked as the 4th most productive manufacturing state in the country, behind California, Texas, and Ohio.[93] About three-quarters of the state's manufacturers are located in the Northeastern Opportunity Return Region, with 38 percent of Illinois' approximately 18,900 manufacturing plants located in Cook County. As of 2006, the leading manufacturing industries in Illinois, based upon value-added, were chemical manufacturing ($18.3 billion), machinery manufacturing ($13.4 billion), food manufacturing ($12.9 billion), fabricated metal products ($11.5 billion), transportation equipment ($7.4 billion), plastics and rubber products ($7.0 billion), and computer and electronic products ($6.1 billion).[94]

Services

By the early 2000s, Illinois' economy had moved toward a dependence on high-value-added services, such as financial trading, higher education, law, logistics, and medicine. In some cases, these services clustered around institutions that hearkened back to Illinois' earlier economies. For example, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a trading exchange for global derivatives, had begun its life as an agricultural futures market. Other important non-manufacturing industries include publishing, tourism, and energy production and distribution.

Energy

Illinois is a net importer of fuels for energy, despite large coal resources and some minor oil production. Illinois exports electricity, ranking fifth among states in electricity production and seventh in electricity consumption.[95]

Coal

The coal industry of Illinois has its origins in the middle 19th century, when entrepreneurs such as Jacob Loose discovered coal in locations such as Sangamon County. Jacob Bunn contributed to the development of the Illinois coal industry, and was a founder and owner of the Western Coal & Mining Company of Illinois. About 68% of Illinois has coal-bearing strata of the Pennsylvanian geologic period. According to the Illinois State Geological Survey, 211 billion tons of bituminous coal are estimated to lie under the surface, having a total heating value greater than the estimated oil deposits in the Arabian Peninsula.[96] However, this coal has a high sulfur content, which causes acid rain unless special equipment is used to reduce sulfur dioxide emissions.[24][26][44] Many Illinois power plants are not equipped to burn high-sulfur coal. In 1999, Illinois produced 40.4 million tons of coal, but only 17 million tons (42%) of Illinois coal was consumed in Illinois. Most of the coal produced in Illinois is exported to other states and countries. In 2008, Illinois exported 3 million tons of coal and was projected to export 9 million tons in 2011, as demand for energy grows in places such as China, India, elsewise in Asia and Europe.[97] As of 2010, Illinois is was ranked third in recoverable coal reserves at producing mines in the Nation.[89] Most of the coal produced in Illinois is exported to other states, while much of the coal burned for power in Illinois (21 million tons in 1998) is mined in the Powder River Basin of Wyoming.[95]

Mattoon was recently chosen as the site for the Department of Energy's FutureGen project, a 275 megawatt experimental zero emission coal-burning power plant which just received a second round of funding from the DOE. In 2010, after a number of setbacks, the city of Mattoon backed out of the project.[98]

Petroleum

Illinois is a leading refiner of petroleum in the American Midwest, with a combined crude oil distillation capacity of nearly 900,000 barrels per day (140,000 m3/d). However, Illinois has very limited crude oil proved reserves that account for less than 1% of U.S. crude oil proved reserves. Residential heating is 81% natural gas compared to less than 1% heating oil. Illinois is ranked 14th in oil production among states, with a daily output of approximately 28,000 barrels (4,500 m3) in 2005.[99][100]

Nuclear power

Nuclear power arguably began in Illinois with the Chicago Pile-1, the world's first artificial self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction in the world's first nuclear reactor, built on the University of Chicago campus. There are six operating nuclear power plants in Illinois: Braidwood; Byron; Clinton; Dresden; LaSalle; and Quad Cities.[101] With the exception of the single-unit Clinton plant, each of these facilities has two reactors. Three reactors have been permanently shut down and are in various stages of decommissioning: Dresden-1 and Zion-1 and 2. Illinois ranked first in the nation in 2010 in both nuclear capacity and nuclear generation. Generation from its nuclear power plants accounted for 12 percent of the Nation’s total.[89] In 2007, 48% of Illinois' electricity was generated using nuclear power.[102]

Wind power

Illinois has seen growing interest in the use of wind power for electrical generation.[103] Most of Illinois was rated in 2009 as "marginal or fair" for wind energy production by the U.S. Department of Energy, with some western sections rated "good" and parts of the south rated "poor".[104] These ratings are for wind turbines with 50-metre (160 ft) hub heights; newer wind turbines are taller, enabling them to reach stronger winds farther from the ground. As a result, more areas of Illinois have become prospective wind farm sites. As of September 2009, Illinois had 1116.06 MW of installed wind power nameplate capacity with another 741.9 MW under construction.[105] Illinois ranked ninth among U.S. states in installed wind power capacity, and sixteenth by potential capacity.[105] Large wind farms in Illinois include Twin Groves, Rail Splitter, EcoGrove, and Mendota Hills.[105]

As of 2007, wind energy represented only 1.7% of Illinois' energy production, and it was estimated that wind power could provide 5–10% of the state's energy needs.[106][107] Also, the Illinois General Assembly mandated in 2007 that by 2025, 25% of all electricity generated in Illinois is to come from renewable resources.[108]

Biofuels

Illinois is ranked second in corn production among U.S. states, and Illinois corn is used to produce 40% of the ethanol consumed in the United States.[88] The Archer Daniels Midland corporation in Decatur, Illinois is the world's leading producer of ethanol from corn.

The National Corn-to-Ethanol Research Center (NCERC), the world's only facility dedicated to researching the ways and means of converting corn (maize) to ethanol is located on the campus of Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.[109][110]

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is one of the partners in the Energy Biosciences Institute (EBI), a $500 million biofuels research project funded by petroleum giant BP.[111][112]

Arts and culture

Museums

Illinois has numerous museums; the greatest concentration of these is in Chicago. Numerous museums in the city of Chicago are considered some of the best in the world. These include the John G. Shedd Aquarium, the Field Museum of Natural History, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Adler Planetarium, and the Museum of Science and Industry.

The modern Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield is the largest and most attended presidential library in the country. Other historical museums in the state include the Polish Museum of America in Chicago; Magnolia Manor in Cairo; the Elihu Benjamin Washburne; Ulysses S. Grant Homes, both in Galena; and the Chanute Air Museum, located on the former Chanute Air Force Base in Rantoul.

The Chicago metropolitan area also has two zoos: The very large Brookfield Zoo, located approximately 13 miles west of the city center in suburban Brookfield, contains over 2300 animals and covers 216 acres (87 ha). The Lincoln Park Zoo is located in huge Lincoln Park on Chicago's North Side, approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the Loop. The zoo covers over 35 acres (14 ha) within the park.

Music

Illinois is a leader in music education having hosted the Midwest Clinic: An International Band and Orchestra Conference since 1946, as well being home to the Illinois Music Educators Association (IMEA), one of the largest professional music educator's organizations in the country. Each summer since 2004, Southern Illinois University Carbondale has played host to the Southern Illinois Music Festival, which presents dozens of performances throughout the region. Past featured artists include the Eroica Trio and violinist David Kim.

Sports

Major league teams

As one of the United States' major metropolises, all major sports leagues have teams headquartered in Chicago.

- Two Major League Baseball teams are located in the state. The Chicago Cubs of the National League play in the second-oldest major league stadium (Wrigley Field) and are widely known for having the longest championship drought in all of major American sport: not winning the World Series since 1908.[113][114] The Chicago White Sox of the American League won the World Series in 2005, their first since 1917. They play on the City's south side at U.S. Cellular Field.

- The Chicago Bears football team has won nine total NFL Championships, the last occurring in Super Bowl XX in 1985.

- The Chicago Bulls of the NBA is one of the most recognized basketball teams in the world, due largely to the efforts of Michael Jordan, who led the team to six NBA championships in eight seasons in the 1990s.

- The Chicago Blackhawks of the NHL began playing in 1926, as a member of the Original Six and have won five Stanley Cups, most recently in 2013.

- The Chicago Fire soccer club is a member of MLS and is one of the league's most successful and best-supported, since its founding in 1997, winning one league and four Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cups in that timespan.

Minor league teams

Many minor league teams also call Illinois their home. They include:

- The Chicago Red Stars of the NWSL previously played in the Women's Professional Soccer League (WPS) and the Women's Premier Soccer League (WPSL)[115]

- The Chicago Wolves are an AHL team.

- The Chicago Sky of the WNBA

- The Chicago Bandits of the NPF, a female softball league; the Bandits won their first title in 2008

- The Peoria Chiefs of the Midwest League.

- The Peoria Rivermen are an SPHL team.

- The Rockford IceHogs are an AHL team.

- The Kane County Cougars of the Midwest League.

- The Southern Illinois Miners based out of Marion in the Southern part of the state

- The Chicago Carnage of the MLRH is the most recent professional team in Chicago.

Former Chicago sports franchises

Folded teams

The city was formerly home to several other teams that either failed to survive, or that belonged to leagues that folded.

- The Chicago Blitz, United States Football League

- The Chicago Sting, Major Indoor Soccer League

- The Chicago Cougars, World Hockey Association

- The Chicago Rockers, Continental Basketball Association

- The Chicago Skyliners, American Basketball Association

- The Chicago Bruisers, Arena Football League

- The Chicago Power, National Professional Soccer League

- The Chicago Blaze, National Women's Basketball League.

- The Chicago Machine, Major League Lacrosse

- The Chicago Whales of the Federal Baseball League, a rival league to the National and American Leagues from 1914-1916

- The Chicago Express of the ECHL

- The Chicago Enforcers of the XFL, a Professional Football League owned by Vince McMahon

Relocated teams

The NFL's Arizona Cardinals, who currently play in Phoenix, Arizona, played in Chicago as the Chicago Cardinals, until moving to St. Louis, Missouri after the 1959 season. An NBA expansion team known as the Chicago Packers in 1961–62 and the Chicago Zephyrs the following year moved to Baltimore after the 1962–63 season. The franchise is now known as the Washington Wizards.

Professional sports teams outside of Chicago

The Rockford Lightning is one of the oldest CBA teams in the league. The Peoria Chiefs and Kane County Cougars are minor league baseball teams affiliated with MLB. The Schaumburg Boomers and Lake County Fielders are members of the North American League, and the Southern Illinois Miners, Gateway Grizzlies, Joliet Slammers, Windy City ThunderBolts and Normal CornBelters belong to the Frontier League.

In addition to the Chicago Wolves, the AHL also has the Rockford IceHogs serving as the AHL affiliate of the Chicago Blackhawks. The second incarnation of the Peoria Rivermen plays in the SPHL.

Motor racing

Motor racing oval tracks at the Chicagoland Speedway in Joliet, the Chicago Motor Speedway in Cicero and the Gateway International Raceway in Madison, near St. Louis, have hosted NASCAR, CART, and IRL races, whereas the Sports Car Club of America, among other national and regional road racing clubs, have visited the Autobahn Country Club in Joliet, the Blackhawk Farms Raceway in South Beloit and the former Meadowdale International Raceway in Carpentersville. Illinois also has several short tracks and dragstrips. The dragstrip at Gateway International Raceway and the Route 66 Raceway, which sits on the same property as the Chicagoland Speedway, both host NHRA drag races.

Parks and recreation

The Illinois state parks system began in 1908 with what is now Fort Massac State Park, becoming the first park in a system encompassing over 60 parks and about the same number of recreational and wildlife areas.

Areas under the protection and control of the National Park Service include: the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor near Lockport;[116] the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail; the Lincoln Home National Historic Site in Springfield; the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail; the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail; and the American Discovery Trail.[117]

Government

The government of Illinois, under the Constitution of Illinois, has three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial. The executive branch is split into several statewide elected offices, with the Governor as chief executive. Legislative functions are granted to the Illinois General Assembly. The judiciary is composed of the Supreme Court and lower courts.

The Illinois General Assembly is the state legislature, composed of the 118-member Illinois House of Representatives and the 59-member Illinois Senate. The members of the General Assembly are elected at the beginning of each even-numbered year. The Governor has different types of veto like a full veto, reduction veto, and amendatory veto, but the General Assembly has the power to override gubernatorial vetoes through a three-fifths majority vote in each chamber.

The executive branch is composed of six elected officers and their offices as well as numerous other departments.[118] The six elected officers are the:[118] Governor, Lieutenant Governor, Attorney General, Secretary of State, Comptroller, and Treasurer.

The government of Illinois has numerous departments, agencies, boards and commissions, but the so-called code departments provide most of the state's services.[118][119]

The Judiciary of Illinois is the unified court system of Illinois. It consists of the Supreme Court, Appellate Court, and Circuit Courts. The Supreme Court oversees the administration of the court system.

The administrative divisions of Illinois are counties, townships, precincts, cities, towns, villages, and special-purpose districts.[120] The basic subdivision of Illinois are the 102 counties.[121] 85 of the 102 counties are in turn divided into townships and precincts.[121][122] Municipal governments are the cities, villages, and incorporated towns.[121] Localities possess "home rule", which allows them to govern themselves to a certain extent.[123]

Politics

Party balance

Historically, Illinois was long a major swing state, with near-parity existing between the Republican and the Democratic parties. However, in recent elections, the Democratic Party has gained ground and Illinois has come to be seen as a "blue" state.[124][125] Chicago and most of Cook County votes have long been strongly Democratic. However, the "collar counties" (the suburbs surrounding Chicago's Cook County, Illinois), can be seen as a Republican stronghold.[126][127]

Republicans continue to prevail in the Chicago suburban "collar counties" surrounding Cook County, as well as rural northern and central Illinois; Republican support is also strong in southern Illinois, outside of the East St. Louis metropolitan area. From 1920 until 1972, the state was carried by the victor of each of these presidential elections - 14 elections.[128] In fact, Illinois was long seen as a national bellwether,[129] supporting the winner in every election in the 20th Century except for 1916 and 1976. By contrast, Illinois has trended more toward the Democratic party and such, has voted for their presidential candidates in the last six elections; in 2000, George W. Bush became the first Republican to win the presidency without carrying Illinois or Vermont. Native son and current president Barack Obama easily won the state's 21 electoral votes in 2008, with 61.9% of the vote.

History of corruption

Politics in the state have been infamous for highly visible corruption cases, as well as for crusading reformers, such as governors Adlai Stevenson and James R. Thompson. In 2006, former Governor George Ryan was convicted of racketeering and bribery, leading to a 6 and a half year prison sentence. In 2008, then-Governor Rod Blagojevich was served with a criminal complaint on corruption charges, stemming from allegations that he conspired to sell the vacated Senate seat left by President Barack Obama to the highest bidder. Subsequently, on December 7, 2011, Rod Blagojevich was sentenced to 14 years in prison for those charges, as well as perjury while testifying during the case, totaling 18 convictions. In the late 20th century, Congressman Dan Rostenkowski was imprisoned for mail fraud; former governor and federal judge Otto Kerner, Jr. was imprisoned for bribery; and State Auditor of Public Accounts (Comptroller) Orville Hodge was imprisoned for embezzlement. In 1912, William Lorimer, the GOP boss of Chicago, was expelled from the U.S. Senate for bribery and in 1921, Governor Len Small was found to have defrauded the state of a million dollars.[26][44][130]

US Presidents from Illinois

Three presidents have claimed Illinois as their political base: Lincoln, Grant, and Obama. Lincoln was born in Kentucky, but moved to Illinois at the age of 21; he served in the General Assembly and represented the 7th congressional district in the US House of Representatives before his election as President. Ulysses S. Grant was born in Ohio and had a military career that precluded settling down, but on the eve of the Civil War, and approaching middle age, Grant moved to Illinois and thus claimed it as his home when running for President. Barack Obama was born and raised in Hawaii (other than a four-year period of his childhood spent in Indonesia) and made Illinois his home and base after completing law school.

Only one person elected President of the United States was actually born in Illinois. Ronald Reagan was born in Tampico, raised in Dixon and educated at Eureka College. Reagan moved to Los Angeles as a young adult and later became Governor of California before being elected President.

Black US senators

Nine African-Americans have served as members of the United States Senate. Three of them have represented Illinois, the most of any single state: Carol Moseley-Braun, Barack Obama,[131] and Roland Burris, who was appointed to replace Obama after his election to the presidency. Moseley-Braun was the first and to date only African-American woman to become a U.S. Senator.

Political families

Two families from Illinois have played particularly prominent roles in the Democratic Party, gaining both statewide and national fame.

Stevensons

The Stevenson family, rooted in central Illinois, has provided four generations of Illinois elected leadership.

- Adlai Stevenson I (1835–1914) was a Vice President of the United States, as well as a Congressman

- Lewis Stevenson (1868–1932), son of Adlai, served as Illinois Secretary of State.

- Adlai Stevenson II (1900–1965), son of Lewis, served as Governor of Illinois and as the US Ambassador to the United Nations; he was also the Democratic party's presidential nominee in 1952 and 1956, losing both elections to Dwight Eisenhower.

- Adlai Stevenson III (1930– ), son of Adlai II, served ten years as a United States Senator.

Daleys

The Daley family's powerbase was in Chicago.

- Richard J. Daley (1902–1976) served as Mayor of Chicago from 1955 to his death.

- Richard M. Daley (1942– ), son of Richard J, was Chicago's longest serving mayor, in office from 1989–2011.

- William M. Daley (1948– ), another son of Richard J, is a former White House Chief of Staff and has served in a variety of appointed positions.

Education

Illinois State Board of education

The Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) is autonomous of the governor and the state legislature, and administers public education in the state. Local municipalities and their respective school districts operate individual public schools but the ISBE audits performance of public schools with the Illinois School Report Card. The ISBE also makes recommendations to state leaders concerning education spending and policies.

Primary and secondary schools

Education is compulsory from ages 7 to 17 in Illinois. Schools are commonly but not exclusively divided into three tiers of primary and secondary education: elementary school, middle school or junior high school, and high school. District territories are often complex in structure. Many areas in the state are actually located in two school districts—one for high school, the other for elementary and middle schools. And such districts do not necessarily share boundaries. A given high school may have several elementary districts that feed into it, yet some of those feeder districts may themselves feed into multiple high school districts.

Colleges and universities

Using the criterion established by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, there are eleven "National Universities" in the state. As of 19 August 2010[update], five of these rank in the "first tier" (that is, the top quartile) among the top 500 National Universities in the United States, as determined by the U.S. News & World Report rankings: the University of Chicago (4), Northwestern University (12), the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (41), Loyola University Chicago (106), and the Illinois Institute of Technology (113).[132]

The University of Chicago is continuously ranked as one of the world's top ten universities on various independent university rankings and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign consistently ranks among the best engineering schools in the world and in United States.

Illinois also has more than 20 additional accredited four-year universities, both public and private, and dozens of small liberal arts colleges across the state. Additionally, Illinois supports 49 public community colleges in the Illinois Community College System.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Because of its central location and its proximity to the Rust Belt and Grain Belt, Illinois is a national crossroads for air, auto, rail, and truck traffic.

Airports

From 1962 until 1998, Chicago's O'Hare International Airport (ORD) was the busiest airport in the world, measured both in terms of total flights and passengers. While it was surpassed by Atlanta's Hartsfield in 1998, with 59.3 million domestic passengers annually, along with 11.4 million international passengers in 2008,[133] O'Hare remains one of the two or three busiest airports in the world, and some years still ranks number one in total flights. It is a major hub for United Airlines and American Airlines, and a major airport expansion project is currently underway. Chicago Midway International Airport (MDW), which had been the busiest airport in the world until supplanted by O'Hare in 1962, is now the secondary airport in the Chicago metropolitan area. For a time in the late 1960s and 1970s, Midway was nearly vacant except for general aviation, but growth in the area, combined with political deadlock over the building of a new major airport in the region, has caused a resurgence for Midway. It is now a major hub for Southwest Airlines, and services many other airlines as well. Midway served 17.3 million domestic and international passengers in 2008.[134]

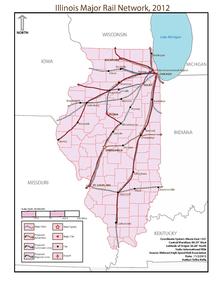

Rail

Illinois has an extensive passenger and freight rail transportation network. Chicago is a national Amtrak hub and in-state passengers are served by Amtrak's Illinois Service, featuring the Chicago to Carbondale Illini and Saluki, the Chicago to Quincy Carl Sandburg and Illinois Zephyr, and the Chicago to St. Louis Lincoln Service. Currently there is trackwork on the Chicago–St. Louis line to bring the maximum speed up to 110 mph (180 km/h), which would reduce the trip time by an hour and a half. Nearly every North American railway meets at Chicago, making it the largest and most active rail hub in the country. Extensive commuter rail is provided in the city proper and some immediate suburbs by the Chicago Transit Authority's 'L' system. The largest suburban commuter rail system in the United States, operated by Metra, uses existing rail lines to provide direct commuter rail access for hundreds of suburbs to the city and beyond.

In addition to the state's rail lines, the Mississippi River and Illinois River provide major transportation routes for the state's agricultural interests. Lake Michigan gives Illinois access to the Atlantic Ocean by way of the Saint Lawrence Seaway.

Interstate highway system

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Illinois is among many US states with a well developed interstate highway system. Illinois has the distinction of having the most primary (two-digit) interstates pass through it among all the 50 states, tied with Pennsylvania with 12, as well as the 3rd most interstate mileage behind California and Texas.[135]

Major U.S. Interstate highways crossing the state include: Interstate 24 (I-24), I-39, I-55, I-57, I-64, I-70, I-72, I-74, I-80, I-88, I-90, and I-94.

U.S. highway system

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Among the U.S. highways that pass through the state, the primary ones are: U.S. Route 6 (US 6), US 12, US 14, US 20, US 24, US 30, US 34, US 36, US 40, US 41, US 45, US 50, US 52, US 54, US 60, and US 62.

Gallery

-

Current standard license plate introduced in 2001.

-

Illinois license plate design used throughout the 1980s and 1990s, displaying the Land of Lincoln slogan that has been featured on the state's plates since 1954.

See also

- Outline of Illinois – organized list of topics about Illinois

- Index of Illinois-related articles

References

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012" (CSV). 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. December 2012. Retrieved December 22, 2012.

- ^ "(5 ILCS 460/20) (from Ch. 1, par. 2901‑20) State Designations Act". Illinois Compiled Statutes. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois General Assembly. September 4, 1991. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

Sec. 20. Official language. The official language of the State of Illinois is English.

- ^ "Illinois Table: QT-P16; Language Spoken at Home: 2000". Data Set: Census 2000 Summary File 3 (SF 3) – Sample Data. U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ "Charles". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ a b Ohlemacher, Stephen (May 17, 2007). "Analysis ranks Illinois most average state". Carbondale, Illinois: The Southern Illinoisan. Associated Press. Retrieved April 10, 2009.

- ^ "Chicago's Front Door: Chicago Harbor." A digital exhibit published online by the Chicago Public Library. [1][dead link]. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ "Jazz". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ "Blues". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ "The History of Illinois License Plates". Cyberdriveillinois.com. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ "Slogan". Museum.state.il.us. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ Fay, J. (2009) Eriniouaj. Retrieved October 21, 2009 from http://www.illinoisprairie.info/Eriniouaj.htm.

- ^ Hodge, Frederick Webb (1911). Handbook of American Indians north of Mexico, Volume 1. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. p. 597. OCLC 26478613.

- ^ Stewart, George R. (1967) [1945]. Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States (Sentry (3rd) ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ "Illinois Symbols". State of Illinois. Retrieved April 20, 2006.

- ^ Callary, Edward (2008). Place Names of Illinois. University of Illinois Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-252-03356-8.

- ^ Costa, David J. (January 2007). "Three American Placenames: Illinois" (PDF). Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas Newsletter. 25 (4): 9–12. ISSN 1046-4476. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Timothy R., Pauketat (2009). Cahokia : Ancient Americas Great City on the Mississippi. Viking Press. pp. 23–34. ISBN 978-0-670-02090-4.

Pg 23 "Cahokia was so large-covering three to five square miles-that archaeologists have yet to probe many portions of it. Its centerpiece was an open fifty-acre Grand Plaza, surrounded by packed-clay pyramids. The size of thirty-five football fields, the Grand Plaza was at the time the biggest public space ever conceived and executed north of Mexico."...Pg 34 "a flat public square 1,600-plus feet in length and 900-plus feet in width

- ^ Skele, Mike (1988). "The Great Knob". Studies in Illinois Archaeology (4). Springfield, Illinois: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. ISBN 0-942579-03-8.

- ^ Snow, Dean (2010). Archaeology of Native North Americas. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 201–203.

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. p. 59. ISBN 0-8263-2871-7.

- ^ E. Hoxie, Encyclopedia of North American Indians (1996) 266-7, 506

- ^ a b c d e f g h Nelson, Ronald E. (ed.), ed. (1978). Illinois: Land and Life in the Prairie State. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt. ISBN 0-8403-1831-6.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|chapterurl=and|origdate=(help) - ^ de L'Isle, Guillaume (1718). "Carte de la Louisiane et du Cours du Mississipi. 1718". An Exhibition of Maps and Navigational Instruments on View. Tracy W. McGregor Room, Alderman Library: University of Virginia. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Biles, Roger (2005). Illinois: A History of the Land and its People. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-87580-349-0.

- ^ "Full Remarks from Dave M". Sancohis.org. March 16, 2010. Retrieved February 7, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln and Springfield – Abraham Lincoln's Classroom". Abrahamlincolnsclassroom.org. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ "The other Illinois: How Egypt lost its clout – Chicago Tribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. June 24, 2001. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Southern Illinois Backroads Tourism: In Little Egypt it means bluffs, Superman, even scuba diving » Evansville Courier & Press". Courierpress.com. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ Paul Finkelman, Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson, (2001), p 78

- ^ James Pickett Jones, Black Jack: John A. Logan and Southern Illinois in the Civil War Era 1967 ISBN 0-8093-2002-9.

- ^ "Black Hawk War". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832". Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Duff, Judge Andrew D. Egypt - Republished, Springhouse Magazine, accessed May 1, 2006.

- ^ Roland Tweet, Miss Gale's Books: The Beginnings of the Rock Island Public Library, (Rock Island, IL: Rock Island Public Library, 1997), 15.

- ^ "Illinois Infantry, Cavalry, and Artillery Units", Illinois in the Civil War, Retrieved November 26, 2006

- ^ a b "Illinois – Race and Hispanic Origin: 1800 to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.111

- ^ "ComEd and Electricity Related Messages for Economic Development" (PDF). Retrieved February 7, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ https://www.comed.com/Documents/about-us/economic-development/ComEd_and_Electricity_Related_EconDev_Messages_-_January_2012.pdf

- ^ Painter, George (August 10, 2004). "The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States: Illinois". The Sensibilities of Our Forefathers. Gay & Lesbian Archives of the Pacific Northwest. Retrieved January 12, 2012.

- ^ Wikisource. Illinois Constitution of 1818.

- ^ a b c d e Horsley, A. Doyne (1986). Illinois: A Geography. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0-86531-522-1.

- ^ Illinois State Climatologist Office. Climate Maps for Illinois. Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- ^ NWS Chicago, IL (November 2, 2005). "Public Information Statement". Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ^ Weather Underground (January 15, 2009). "Weather History for Rochelle, IL". Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Annual average number of tornadoes, 1953–2004", NOAA National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved October 24, 2006.

- ^ PAH Webmaster (November 2, 2005). "NWS Paducah, KY: NOAA/NWS 1925 Tri-State Tornado Web Site – General Information". Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ "Average Weather for Cairo, IL",weather.com

- ^ "Chicago Weather[dead link]", ustravelweather.com

- ^ "Average Weather for Edwardsville, IL - Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. January 17, 2007. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ "Moline Weather[dead link]", ustravelweather.com

- ^ "Peoria Weather[dead link]", ustravelweather.com

- ^ "Rockford Weather[dead link]", ustravelweather.com

- ^ "Springfield Weather[dead link]", ustravelweather.com

- ^ Resident Population Data. "Resident Population Data – 2010 Census". 2010.census.gov. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013". Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Illinois QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau. Quickfacts.census.gov. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For The United States, Regions, Divisions, and States

- ^ Population of Illinois: Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts

- ^ 2010 Census Data

- ^ "Illinois QuickFacts". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Exner, Rich (June 3, 2012). "Americans under age 1 now mostly minorities, but not in Ohio: Statistical Snapshot". The Plain Dealer.

- ^ a b "Illinois Selected Social Characteristics in the United States: 2007". 2007 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. 2007. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ "Illinois QuickFacts". U.S. Census Bureau. February 20, 2009. Retrieved April 9, 2009.

- ^ "Population and Population Centroid by State: 2000". American Congress on Surveying & Mapping. 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ "Table 1: Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places Over 100,000, Ranked by July 1, 2008 Population: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2008 (SUB-EST2008-01)". 2008 Population Estimates. Population Division, United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Ryan, Camille (August 2013). "Language Use in the United States: American Community Survey Reports" (PDF). Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ Baron, Dennis. "Do You Speak American?". PBS.org. PBS. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

- ^ McCormick, Washington J. "American as Official Language of the United States". Language Policy Web Site. James Crawford. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Mount, Steve. "Constitutional Topic: Official Language". 2014 usconstitution.net. Steve Mount. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Baron, Dennis. "Language Laws and Related Court Decisions". English Education Illinois. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ^ Kosmin, Barry A.; Mayer, Egon; Keysar, Ariela (December 19, 2001). "State by State Distribution of Selected Religious Groups" (PDF). American Religious Identification Survey 2001. The Graduate Center of the City University of New York. p. 39. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Roman Catholicism percentage of catholics statistics - states compared - People data on StateMaster". Statemaster.com. May 15, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

- ^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | State Membership Report". www.thearda.com. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives | County Membership Report". www.thearda.com. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ "Newsroom – The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints". Newsroom.lds.org. Retrieved February 7, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ a b "GDP by State". Greyhill Advisors. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ "Table 2. Annual Personal Income and Per Capita Personal Income by State and Region" (PDF). Survey of Current Business – Bureau of Economic Analysis. U.S. Department of Commerce. April 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- ^ "State Data Lab "Snapshot By The Numbers: Illinois". January 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ "Current Unemployment Rates for States and Historical Highs/Lows". Local Area Unemployment Statistics Information and Analysis. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. April 16, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- ^ "Local Area Unemployment Statistics". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ Pierog, Karen (January 12, 2011). "Illinois lawmakers pass big tax hike to aid budget". Reuters. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- ^ Illinois Department of Revenue. Individual Income Tax. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ Illinois Department of Revenue. Illinois Sales Tax Reference Manual (PDF). p133. January 1, 2006.

- ^ "Soybean Production by State 2008". Soy Stats. The American Soybean Association. 2009. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ a b "Ethanol Fact Sheet". Illinois Corn Growers Association. 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b c http://www.eia.gov/state/?sid=IL

- ^ a b Facts About Illinois Agriculture, Illinois Department of Agriculture. Accessed online April 16, 2012

- ^ "Meatpacking in Illinois History by Wilson J. Warren, Illinois History Teacher, 3:2, 2006. Access online April 16, 2012.

- ^ http://americanroads.net/agri_trails_winter2014.htm

- ^ http://www.ildceo.net/NR/rdonlyres/1357C591-2810-4228-A334-E8B55EF1288D/0/Manufacturing2011.pdf

- ^ "Manufacturing in Illinois" (PDF). Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity. 2009. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ a b "Illinois in the Global Energy Marketplace", Robert Finley, 2001. Illinois State Geological Survey publication.

- ^ Illinois State Geological Survey. Coal in Illinois. Retrieved December 4, 2008.

- ^ http://www.ildceo.net/NR/rdonlyres/EA15E8A9-E0BD-468A-A308-BE58E93D0C03/0/CoalInIllinois2011.pdf

- ^ "Illinois Town Gives Up on Futurgen". Permianbasin360.com. August 12, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ United States Department of Energy. Petroleum Profile: Illinois[dead link]. Retrieved April 4, 2006.

- ^ "Illinois – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". Eia.gov. April 19, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Nuclear State Profiles". Eia.gov. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Illinois Nuclear Industry". U.S. Energy Information Administration. November 6, 2009. Retrieved January 29, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Illinois Wind." Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University Illinoiswind.com

- ^ "Illinois Wind Activities". EERE. U.S. Department of Energy. October 20, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Wind Energy Projects – Illinois". American Wind Energy Association. September 30, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Wind Power on the Illinois Horizon", Rob Kanter, September 14, 2006. University of Illinois Environmental Council.

- ^ "Illinois Renewable Electricity Profile". U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ^ Olbert, Lori (December 13, 2007). "Wind Farm Conference Tackles Complicated Issue". CIProud.com. WYZZ-TV/WMBD-TV. Retrieved January 15, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ http://illinoisrfa.org/research/

- ^ http://www.stlrcga.org/documents/corn%20to%20ethanol.pdf

- ^ "BP Pledges $500 Million for Energy Biosciences Institute and Plans New Business to Exploit Research". Bp.com. June 14, 2006. Retrieved May 19, 2012.