Three wise monkeys

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2010) |

The three wise monkeys (Japanese: 三猿, san'en or sanzaru, or 三匹の猿, sanbiki no saru, literally "three monkeys"), sometimes called the three mystic apes,[1] are a pictorial maxim. Together they embody the proverbial principle to "see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil".[2] The three monkeys are Mizaru, covering his eyes, who sees no evil; Kikazaru, covering his ears, who hears no evil; and Iwazaru, covering his mouth, who speaks no evil.

There are various meanings ascribed to the monkeys and the proverb including associations with being of good mind, speech and action. In the Western world the phrase is often used to refer to those who deal with impropriety by turning a blind eye.[3]

In English, the monkeys' names are often given as Mizaru,[4] Mikazaru,[5] and Mazaru,[6] as the last two names were corrupted from the Japanese originals.[7][8]

Origin

The source that popularized this pictorial maxim is a 17th-century carving over a door of the famous Tōshō-gū shrine in Nikkō, Japan. The carvings at Toshogu Shrine were carved by Hidari Jingoro, and believed to have incorporated Confucius’s Code of Conduct, using the monkey as a way to depict man’s life cycle. There are a total of 8 panels, and the iconic three wise monkeys picture comes from panel 2. The philosophy, however, probably originally came to Japan with a Tendai-Buddhist legend, from China in the 8th century (Nara Period). It has been suggested that the figures represent the three dogmas of the so-called middle school of the sect.

In Chinese, a similar phrase exists in the Analects of Confucius from 2nd to 4th century B.C.: "Look not at what is contrary to propriety; listen not to what is contrary to propriety; speak not what is contrary to propriety; make no movement which is contrary to propriety" (非禮勿視, 非禮勿聽, 非禮勿言, 非禮勿動).[9] It may be that this phrase was shortened and simplified after it was brought into Japan.

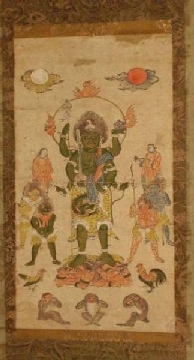

It is through the Kōshin rite of folk religion that the most significant examples are presented. The Kōshin belief or practice is a Japanese folk religion with Chinese Taoism origins and ancient Shinto influence. It was founded by Tendai Buddhist monks in the late 10th century. A considerable number of stone monuments can be found all over the eastern part of Japan around Tokyo. During the later part of the Muromachi period, it was customary to display stone pillars depicting the three monkeys during the observance of Kōshin.

Though the teaching had nothing to do with monkeys, the concept of the three monkeys originated from a simple play on words. The saying in Japanese is mizaru, kikazaru, iwazaru (見ざる, 聞かざる, 言わざる) "don't see, don't hear, don't speak",[clarification needed] However, -zaru, an archaic negative verb conjugation, is pronounced the same as zaru, the vocalized form of saru (猿), "monkey", so the saying can also be interpreted as the names of three monkeys.

It is also possible that the three monkeys came from a more central root than a play on words.[contradictory] The shrine at Nikko is a Shinto shrine, and the monkey is an extremely important being in the Shinto religion.[citation needed] The monkey is believed to be the messenger of the Hie Shinto shrines, which also have connections with Tendai Buddhism. There are even important festivals that are celebrated during the year of the Monkey (occurring every twelve years) and a special festival is celebrated every sixteenth year of the Kōshin.

"The Three Mystic Apes" (Sambiki Saru) were described as "the attendants of Saruta Hito no Mikoto or Kōshin, the God of the Roads".[10] The Kōshin festival was held on the 60th day of the calendar. It has been suggested that during the Kōshin festival, according to old beliefs, one’s bad deeds might be reported to heaven "unless avoidance actions were taken…." It has been theorized that the three Mystic Apes, Not Seeing, Hearing, or Speaking, may have been the "things that one has done wrong in the last 59 days."

According to other accounts, the monkeys caused the Sanshi and Ten-Tei not to see, say or hear the bad deeds of a person. The Sanshi (三尸) are three worms living in everyone's body. The Sanshi keep track of the good deeds and particularly the bad deeds of the person they inhabit. Every 60 days, on the night called Kōshin-Machi (庚申待), if the person sleeps, the Sanshi will leave the body and go to Ten-Tei (天帝), the Heavenly God, to report about the deeds of that person. Ten-Tei will then decide to punish bad people, making them ill, shortening their time alive, and in extreme cases putting an end to their lives. Those believers of Kōshin who have reason to fear will try to stay awake during Kōshin nights. This is the only way to prevent the Sanshi from leaving their body and reporting to Ten-Tei.

An ancient representation of the 'no see, no hear, no say, no do' can be found in four golden figurines in the Zelnik Istvan Southeast Asian Gold Museum. These golden statues date from the 6th to 8th century. The figures look like tribal human people with not very precise body carvings and strong phallic symbols.[11] This set indicates that the philosophy comes from very ancient roots.

Meaning of the proverb

Just as there is disagreement about the origin of the phrase, there are differing explanations of the meaning of "see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil."

- In Buddhist tradition, the tenets of the proverb are about not dwelling on evil thoughts.[3]

- In the Western world both the proverb and the image are often used to refer to a lack of moral responsibility on the part of people who refuse to acknowledge impropriety, looking the other way or feigning ignorance.[3][12]

- It may also signify a code of silence in gangs, or organised crime.[3]

Variations

Sometimes there is a fourth monkey depicted with the three others; the last one, Shizaru, symbolizes the principle of "do no evil". He may be shown crossing his arms or covering his genitals.

In another variation, a fourth monkey is depicted with a sulking posture and the caption "have no fun".

Cultural influences

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2012) |

The three wise monkeys, and the associated proverb, are known throughout Asia and in the Western world. They have been a motif in pictures, such as the ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock printings) by Keisai Eisen, and are frequently represented in modern culture.

Mahatma Gandhi's one notable exception to his lifestyle of non-possession was a small statue of the three monkeys. Today, a larger representation of the three monkeys is prominently displayed at the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, where Gandhi lived from 1915 to 1930 and from where he departed on his famous salt march. Gandhi's statue also inspired a 2008 artwork by Subodh Gupta, Gandhi's Three Monkeys.[13]

In Planet of the Apes, near the end of the tribunal to determine Taylor's origins, the three orangutan judges strike a Three Wise Monkeys pose, emphasizing their refusal to acknowledge the evidence at odds with their dogma.

The maxim inspired an award-winning 2008 Turkish film by director Nuri Bilge Ceylan called Three Monkeys (Üç Maymun).

Unicode characters

Unicode provides emoticon representations of the monkeys as follows:[14]

- Mizaru: U+1F648 🙈 SEE-NO-EVIL MONKEY

- Kikazaru: U+1F649 🙉 HEAR-NO-EVIL MONKEY

- Iwazaru: U+1F64A 🙊 SPEAK-NO-EVIL MONKEY

See also

- Buddhist Noble Eightfold Path: Right speech & right action

- Humata, Hukhta, Hvarshta, "good thoughts, good words, good deeds" in Zoroastrianism

- Lashon hara, prohibition of gossip in Judaism

- Manasa, vacha, karmana, three Sanskrit words referring to mind, speech and actions

- Three Vajras, a formulation in Tibetan Buddhism referring to body, speech and mind

- The colloquial expression "brass monkey", a possible reference to the three monkeys

Notes

- ^ "Three Mystic Apes" term (1894) predates "Three Wise Monkeys" (1900) in Google Books

- ^ Wolfgang Mieder. 1981. "The Proverbial Three Wise Monkeys," Midwestern Journal of Language and Folklore, 7: 5- 38.

- ^ a b c d Pornpimol Kanchanalak (21 April 2011). "Searching for the fourth monkey in a corrupted world". The Nation. Thailand. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ Oldest reference of the right monkeys' names in English. Source:

- Japan Society of London (1893). Transactions and proceedings of the Japan Society, London, Volume 1. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Co. p. 98.

- ^ Oldest references (1926–1984) for Mikazaru in Google Books

- ^ Oldest reference of Mazaru in Google Books. However, Kikazaru appears right. Source:

- Anderson, Isabel (1920). The spell of Japan. Page. p. 379.

- ^ Worth, Fred L. (1974). The Trivia Encyclopedia. Brooke House. p. 262. ISBN 0-912588-12-8.

- ^ Shipley, Joseph Twadell (2001). The Origins of English Words: A Discursive Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Johns Hopkins University

Press. p. 249. ISBN 0-8018-6784-3.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 29 (help) - ^ Original text: 論語 Template:Zh icon, Analects Template:En icon

- ^ Joly, Henri L. (1908). "Legend in Japanese Art". London, New York: J. Lane. p. 10. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Cultures and Civilisations in Southeast Asia Private Museum in Budapest, Hungary.[failed verification]

- ^ Tom Oleson (29 October 2011). "How about monkey see, monkey DON'T do next time?". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "QMA unveils Gandhi's 'Three Monkeys' at Katara". Qatar Tribune. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Unicode 6.0.0 characters in Emoticons block: SEE-NO-EVIL MONKEY ‹🙈›, HEAR-NO-EVIL MONKEY ‹🙉› and SPEAK-NO-EVIL MONKEY ‹🙊›. Supported by Symbola font.

References

- Titelman, Gregory Y. (2000). Random House Dictionary of America's Popular Proverbs and Sayings (Second Edition ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 0-375-70584-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Archer Taylor, “Audi, Vidi, Tace” and the three monkeys

- A. W. Smith, Folklore, Vol. 104, No. ½ pp. 144–150 ‘On the Ambiguity of the Three Wise Monkeys’