Montgomery Clift

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

Montgomery Clift | |

|---|---|

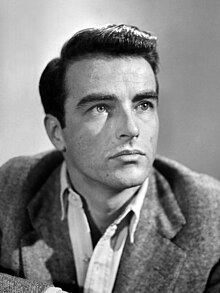

Publicity still of Clift, c. 1948. | |

| Born | Edward Montgomery Clift October 17, 1920 Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1966 (aged 45) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Heart attack brought on by occlusive coronary artery disease |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1933–66 |

Edward Montgomery (Monty) Clift (October 17, 1920 – July 23, 1966) was an American film and stage actor. The New York Times’ obituary of Clift noted his portrayal of "moody, sensitive young men".[1][2]

He often played outsiders and "victim-heroes";[3] examples include the social climber in George Stevens's A Place in the Sun, the anguished Catholic priest in Alfred Hitchcock's I Confess, the doomed regular soldier Robert E. Lee Prewitt in Fred Zinnemann's From Here to Eternity, and the Jewish GI bullied by antisemites in Edward Dmytryk's The Young Lions.

After surviving a car crash in 1956, which left his face partially paralyzed and his profile altered, Clift became addicted to alcohol and prescription drugs, leading to his erratic behavior off screen. Nevertheless, he continued his acting career, playing such parts as "the reckless, alcoholic, mother-fixated rodeo performer" in John Huston's The Misfits and the title role in Huston's Freud: The Secret Passion.

In 1961, Clift portrayed Rudolph Peterson, a victim of forced sterilization at the hands of Nazi authorities in the Stanley Kramer film Judgment at Nuremberg, earning a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[4]

Clift received four Academy Award nominations during his career, three for Best Actor and one for Best Supporting Actor.[5]

Childhood

Clift was born on October 17, 1920, in Omaha, Nebraska. His father, William Brooks Clift, was a vice-president of Omaha National Trust Company.[6] His mother was the former Ethel Fogg Anderson. They had married in 1914.[7] Clift had a twin sister, Roberta (aka Ethel), and a brother, William Brooks Clift, Jr. (1919–1986), who had an illegitimate son with actress Kim Stanley and was later married to political reporter Eleanor Clift.[8] Clift had English, as well as Dutch and Irish ancestry. He resided in Jackson Heights, Queens, until he got his break on Broadway.

Clift's mother's nickname was "Sunny", and was reportedly adopted as a one-year-old. She spent part of her life and her husband's money attempting to establish the Southern lineage that had reportedly been revealed to her at age 18 by the physician who delivered her, Edward Montgomery, after whom she named her younger son. According to Clift biographer Patricia Bosworth, Ethel was the illegitimate daughter of Woodbury Blair and Maria Anderson, whose marriage had been annulled before her birth and subsequent adoption. This would make her a granddaughter of Montgomery Blair, Postmaster General under President Abraham Lincoln, and a great-granddaughter of Francis Preston Blair, a journalist and adviser to President Andrew Jackson, and Levi Woodbury, an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court. However, the relationship between Blair and Anderson has not been proven and, in the absence of documentation, any connection to the Clifts remains in doubt.

As part of Sunny Clift's lifelong preparation for acceptance by her reported biological family, a goal which she never fully achieved, she raised Clift and his siblings as if they were aristocrats. Home-schooled by their mother as well as private tutors in the United States and Europe, in spite of their father's fluctuating finances, they did not attend a regular school until they were in their teens. The adjustment was difficult, particularly for Montgomery. His academic performance lagged behind that of his sister and brother.

Clift was educated in French, German, and Italian. During World War II, he was rejected for military service due to allergies and colitis.[citation needed]

Career

Appearing on Broadway at the age of 15, Clift achieved success and performed on stage for 10 years before moving to Hollywood. At 20, he played the son in the Broadway production of There Shall Be No Night, which won the 1941 Pulitzer Prize for drama, and starred Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne.

Clift's first movie role was opposite John Wayne in the film Red River, which was shot in 1946 and released in 1948. Clift's second movie was The Search. Clift was unhappy with the quality of the script, and rewrote most of it himself. The movie was nominated for a screenwriting Academy Award, but the original writers were credited. Clift's performance saw him nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. His naturalistic performance led to director Fred Zinnemann's being asked, "Where did you find a soldier who can act so well?".

Clift's next movie was The Heiress. He signed on for the movie in order to avoid being typecast. Again unhappy with the script, Clift told friends that he wanted to change his co-star Olivia de Havilland's lines because "she isn't giving me enough to respond [to]." Clift also was unable to get along with most of the cast; he criticized de Havilland, saying that she let the director shape her entire performance.

The studio marketed Clift as a sex symbol prior to the movie's release in 1949. Clift had a large female following, and Olivia De Havilland was flooded with angry fan letters because her character rejects Clift's character in the final scene of the movie. Clift ended up unhappy with his performance, and left early during the movie's premiere.[9]

Clift's next movie was The Big Lift. Although Clift gave another critically acclaimed performance, the movie was a box office failure. Clift was set to appear in Sunset Boulevard (1950), written specifically for him, but he dropped out at the last minute, as he felt that his character was too close to him in real life (like his character, he was good looking, and dating a much older, richer woman).[9]

Prime years

Entering the 1950s, Clift was one of the most sought-after leading men in Hollywood; his only direct competitor was Marlon Brando. According to Elizabeth Taylor (as quoted in Patricia Bosworth's biography of Clift), "Monty could've been the biggest star in the world if he did more movies." Clift was notoriously picky with his projects. His next movie, A Place in the Sun (1951), is one of his iconic roles. The studio paired up two of the biggest young stars in Hollywood at the time (Clift and Taylor) in what was expected to be a blockbuster that would capitalize on their sex symbol status.[9]

Clift's performance in A Place in the Sun is regarded as one of his signature method acting performances. He worked extensively on his character and was again nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. For his character's scenes in jail, Clift spent a night in a real state prison. He also refused to go along with director George Stevens' suggestion that he do "something amazing" on his character's walk to the electric chair. Instead, he walked to his death with a natural, depressed facial expression. His main acting rival, Marlon Brando, was so moved by Clift's performance that he voted for Clift to win the Academy Award for Best Actor and was sure that he would win. That year, Clift voted for Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire. A Place in the Sun was critically acclaimed; Charlie Chaplin called it "the greatest movie made about America." The film received added media attention due to the rumors that Clift and Taylor were dating in real life. They were billed as "the most beautiful couple in Hollywood." Many critics still call Clift and Taylor "the most beautiful Hollywood movie couple of all time."[9]

Clift's next movie was Alfred Hitchcock's I Confess. True to his method, Clift spent a few days in a Catholic monastery and studied priests. The movie was a box office failure due to the controversy over its portrayal of a Catholic priest being romantically involved with a woman.[9]

In the 1953 film From Here to Eternity, Clift worked exceptionally hard on the character of Robert E. Lee Prewitt. For example, in one of his scenes he changed the word "blind" to "see," because he did not feel the former. He also decided that his character would reveal his feelings only while playing the bugle. For this, he learned to play the bugle even though he knew that he would be dubbed by a professional bugler (he said that he wanted his lip movements to be accurate). He acted his character's death scene so realistically that many members of the cast and crew cried. His co-star Burt Lancaster revealed that he was so nervous about being out-acted by Clift that he was shaking during their first scene together in the movie. Once again, Clift received a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Actor. Clift lost out to William Holden, who won for Stalag 17. Allegedly, Clift was unpopular among the Hollywood elite for his refusal to conform to Hollywood standards. For example, he refused to publicize his private life, avoided movie premieres and parties, was usually unavailable for interviews, and preferred to live outside of Los Angeles. Clift was reportedly devastated over his loss and was sent an honorary small golden bugle award by the movie's producers, which he treasured for the rest of his life.[9]

Clift's final completely pre-accident movie was Terminal Station (also known as "Indiscretion of an American Wife"), shot before From Here to Eternity, but released after it. Once again Clift's performance was critically acclaimed; however, the movie bombed at the box office due to its lackluster script.[9]

Clift and Brando, who was also born in Omaha, had reputations as Hollywood rivals because of their rapid rise to stardom and their somewhat similar styles of method acting. Clift was one of James Dean's idols and Dean would sometimes call Clift "just to hear his voice."[9]

Clift reportedly turned down the starring role in East of Eden just as he had for Sunset Boulevard.[10]

Car accident

On the evening of May 12, 1956, while filming Raintree County, Clift was involved in a serious auto accident when he smashed his car into a telephone pole after leaving a dinner party at the Beverly Hills home of his Raintree County co-star and close friend Elizabeth Taylor and her second husband, Michael Wilding. Alerted by friend Kevin McCarthy, who witnessed the accident, Taylor raced to Clift's side, manually pulling a tooth out of his tongue as he had begun to choke on it. He suffered a broken jaw and nose, a fractured sinus, and several facial lacerations which required plastic surgery.[11] In a filmed interview, he later described how his nose could be snapped back into place.

After a two-month recovery, he returned to the set to finish the film. Against the movie studio's worries over profits, Clift correctly predicted the film would do well, if only because moviegoers would flock to see the difference in his facial appearance before and after the accident. Although the results of Clift's plastic surgeries were remarkable for the time, there were noticeable differences in his appearance, particularly the right side of his face. The pain of the accident led him to rely on alcohol and pills for relief, as he had done after an earlier bout with dysentery left him with chronic intestinal problems. As a result, Clift's health and physical appearance deteriorated considerably from then until his death.

Post-accident career

Clift never physically or emotionally recovered from his car accident. His post-accident career has been referred to as the "longest suicide in Hollywood history" by famed acting teacher Robert Lewis because of his alleged subsequent abuse of painkillers and alcohol.[12] He began to behave erratically in public, which embarrassed his friends, including Kevin McCarthy and Jack Larson. Nevertheless, Clift continued to work over the next ten years. His next three films were Lonelyhearts (1958), The Young Lions (1958), and Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). Clift next starred with Lee Remick in Elia Kazan's Wild River in 1960. In 1958, he turned down what became Dean Martin's role as "Dude" in Rio Bravo, which would have reunited him with his co-stars from Red River, John Wayne and Walter Brennan, as well as with Howard Hawks, the director of both films.

Clift then co-starred in John Huston's The Misfits (1961), which was both Marilyn Monroe's and Clark Gable's last film. Monroe, who was also having emotional and substance abuse problems at the time, famously described Clift in a 1961 interview as "the only person I know who is in even worse shape than I am."

By the time Clift was making John Huston's Freud: The Secret Passion (1962), his self-destructive lifestyle was affecting his health. Universal sued him for his frequent absences that caused the film to go over budget. The case was later settled out of court. The film's success at the box office brought numerous awards for screenwriting and directing, but none for Clift himself. In January, 1963, a few weeks after the initial release of Freud, Clift appeared on TV discussion program The Hy Gardner Show, where he spoke at length about the release of his current film; he also talked publicly for the first time about his 1956 car accident and its after effects, as well as his film career, and treatment by the press. During the interview, Gardner mentions that it is the "first and last appearance on a television interview program for Montgomery Clift."

Clift's last nomination for an Academy Award was for Best Supporting Actor for his role in Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), a 12-minute supporting part. He played a developmentally disabled man who had been a victim of the Nazi sterilization program testifying at the Nuremberg trials. The film's director, Stanley Kramer, later wrote in his memoirs that Clift—by this stage a wreck—struggled to remember his lines even for this one scene:

Finally I said to him, "Just forget the damn lines, Monty. Let's say you're on the witness stand. The prosecutor says something to you, then the defense attorney bitterly attacks you, and you have to reach for a word in the script. That's all right. Go ahead and reach for it. Whatever the word may be, it doesn't really matter. Just turn to (Spencer) Tracy on the bench whenever you feel the need, and ad lib something. It will be all right because it will convey the confusion in your character's mind." He seemed to calm down after this. He wasn't always close to the script, but whatever he said fitted in perfectly, and he came through with as good a performance as I had hoped.[13]

Death

On July 22, 1966, Clift spent most of the hot summer day in his bedroom in his New York City townhouse, located at 217 East 61st Street. He and his live-in personal secretary, Lorenzo James, had not spoken much all day. Shortly before 1:00 a.m., James went up to say goodnight to Clift, who was still awake and sitting up in his bed. James asked Clift if he needed anything and Clift politely refused and then told James that he would stay up for a while either to read a book or watch some television. James then noted that The Misfits was on television that night airing as a late-night movie, and he asked Clift if he wanted to watch it with him. "Absolutely not!" was the firm reply. This was the last time Montgomery Clift spoke to anyone. James went to his own bedroom to sleep without saying another word to Clift. At 6:30 a.m. the next day, James woke up and went to wake Clift, but found the bedroom door closed and locked. James became more concerned when Clift did not respond to his knocking on the door. Unable to break the door down, James ran down to the back garden and climbed up a ladder to enter through the second-floor bedroom window. Inside, he found Clift dead: he was undressed, lying on his back in bed, with eyeglasses on and both fists clenched by his side. James then used the bedroom telephone to call the police and an ambulance.

Clift's body was taken to the city morgue less than two miles away at 520 First Avenue and autopsied. The autopsy report cited the cause of death as a heart attack brought on by "occlusive coronary artery disease". No evidence was found that suggested foul play or suicide. It is commonly believed that drug addiction was responsible for Clift's many health problems and his death. In addition to lingering effects of dysentery and chronic colitis, an underactive thyroid was later revealed. The condition (among other things) lowers blood pressure; it may have caused Clift to appear drunk or drugged when he was sober.[14]

Following a 15-minute ceremony at St. James' Church attended by 150 guests, including Lauren Bacall, Frank Sinatra and Nancy Walker, Clift was buried in the Friends [Quaker] Cemetery, Prospect Park, Brooklyn, New York City. Elizabeth Taylor, who was in Rome, sent flowers, as did Roddy McDowall, Myrna Loy and Lew Wasserman.

Relationships

Patricia Bosworth, who had access to Clift's family and many people who knew and worked with him, wrote in her book, "Monty carried on affairs with men and women. After his car accident his addiction included pain killers and became serious. His deepest commitments were emotional and reserved for old friends; he was unflinchingly loyal to women like Elizabeth Taylor, Rhonda Fleming, Maureen O'Hara, Marie Wilson, Dorothy Malone and Lois Chartrand".[9]

Elizabeth Taylor was a significant figure in his life. He met her when she was supposed to be his date at the premiere for The Heiress. They appeared together in A Place in the Sun, where, in their romantic scenes, they received considerable acclaim for their naturalness and their appearance. Clift and Taylor appeared together again in Raintree County and Suddenly, Last Summer.

Because Clift was considered unemployable in the mid 1960s, Taylor put her salary for the film on the line as insurance, in order to have Clift cast as her co-star in Reflections in a Golden Eye.[9] Clift died before the movie was set to shoot. Clift and Taylor remained good friends until his death.

Clift also had a relationship with legendary choreographer Jerome Robbins.[15]

Awards and honors

Clift has been honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6104 Hollywood Boulevard and received four nominations for Academy Awards:

- 1948: Best Actor in a Leading Role—The Search

- 1951: Best Actor in a Leading Role—A Place in the Sun

- 1953: Best Actor in a Leading Role—From Here to Eternity

- 1961: Best Actor in a Supporting Role—Judgment at Nuremberg

The song "The Right Profile" by the English punk rock band The Clash, from their album London Calling, is about the latter life of Clift. The song alludes to his car crash and drug abuse, as well as the movies A Place in the Sun, Red River, From Here to Eternity and The Misfits.

Filmography

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | The Search | Ralph 'Steve' Stevenson | Nominated – Academy Award for Best Actor |

| Red River | Matthew 'Matt' Garth | ||

| 1949 | The Heiress | Morris Townsend | |

| 1950 | The Big Lift | Technical Sergeant Danny MacCullough | |

| 1951 | A Place in the Sun | George Eastman | Nominated – Academy Award for Best Actor |

| 1953 | I Confess | Fr. Michael William Logan | Directed by Alfred Hitchcock |

| Terminal Station | Giovanni Doria | aka Indiscretion of an American Wife | |

| From Here to Eternity | Pvt. Robert E. Lee 'Prew' Prewitt | Nominated – Academy Award for Best Actor | |

| 1957 | Raintree County | John Wickliff Shawnessy | |

| Operation Raintree | Himself | Short subject | |

| 1958 | Lonelyhearts | Adam White | |

| The Young Lions | Noah Ackerman | ||

| 1959 | Suddenly, Last Summer | Dr. Cuckrowicz | |

| 1960 | Wild River | Chuck Glover | Directed by Elia Kazan |

| 1961 | The Misfits | Perce Howland | |

| 1961 | Judgment at Nuremberg | Rudolph Petersen | Nominated – Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor Nominated – BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role Nominated – Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture |

| 1962 | Freud: The Secret Passion | Sigmund Freud | |

| 1966 | The Defector | Prof. James Bower |

Stage appearances

- As Husbands Go (1933)

- Fly Away Home (1935)

- Jubilee (1935)

- Yr. Obedient Husband (1938)

- Eye On the Sparrow (1938)

- The Wind and the Rain (1938)

- Dame Nature (1938)

- The Mother (1939)

- There Shall Be No Night (1940)

- Out of the Frying Pan (1941)

- Mexican Mural (1942)

- The Skin of Our Teeth (1942)

- Our Town (1944)

- The Searching Wind (1944)

- Foxhole in the Parlor (1945)

- You Touched Me (1945)

- The Seagull (1954)

Notes

- ^ Obituary Variety, July 27, 1966.

- ^ "Montgomery Clift Dead at 45; Nominated 3 Times for Oscar; Completed Last Movie, 'The Defector,' in June Actor Began Career at Age 13". The New York Times. July 24, 1966. p. 61, Sunday Page.

- ^ Philip French's Screen LegendsThe Observer Review, January 17, 2010.

- ^ The Observer Review, January 17 2010

- ^ "Montgomery Clift". Oscars.com. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ LaGuardia, p. 6

- ^ LaGuardia, p. 5

- ^ Krampner, Jon (2006). Female Brando: The Legend of Kim Stanley. New York: Back Stage Books. p. 78. ISBN 9780823088478.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bosworth, p. ??

- ^ Capua, p. 92

- ^ "Montgomery Clift Official Site". Cmgww.com. July 23, 1966. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Clarke, Gerald. "Books: Sunny Boy". Time Magazine February 20, 1978.

- ^ Kramer, et al., p. 193.

- ^ McCann, p. 68

- ^ Acocella, Joan (May 28, 2001). "American Dancer". The New Yorker. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

References

- Bosworth, Patricia (1978). Montgomery Clift: A Biography. Hal Leonard Corporation, 2007. N.B.: Also published in mass-market pbk. ed. (New York: Bantam Books, 1979, cop. 1978); originally published by Harcourt, 1978. ISBN 0-87910-135-0 (H. Leonard), 0-553-12455-2 (Bantam).

- Capua, Michelangelo (2002). Montgomery Clift: A Biography. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1432-1.

- Kramer, Stanley and Thomas M. Coffey (1997). A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World: A Life in Hollywood. ISBN 0-15-154958-3.

- LaGuardia, Robert (1977). Monty: A Biography of Montgomery Clift. New York, Avon Books. ISBN 0-380-01887-X (paperback edition)

- McCann, Graham (1991). Rebel Males: Clift, Brando and Dean. H. Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-12884-8.

- The Clash [Punk rock]: London Calling [album] - [track] "The Right Profile"

Lawrence, Amy ( 2010) "The Passion of Montgomery Clift", Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press

Girelli, Elisabetta (2013) "Montgomery Clift Queer Star", Wayne University Press, ISBN9780814339244

External links

- Montgomery Clift at IMDb

- Montgomery Clift at the Internet Broadway Database

- Montgomery Clift at the TCM Movie Database

- Montgomery Clift papers, 1933-1966, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Montgomery Clift papers, Additions, 1929-1969, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- 1920 births

- 1966 deaths

- Male actors from Omaha, Nebraska

- Actors Studio members

- American male film actors

- Cardiovascular disease deaths in New York

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- Bisexual actors

- Bisexual men

- LGBT entertainers from the United States

- People from Jackson Heights, Queens

- Twin people from the United States

- 20th-century American male actors