Septuagint

The Septuagint /ˈsɛptjuːəˌdʒɪnt/, /ˈsɛptuːəˌdʒɪnt/, /ˌsɛpˈtuːədʒɪnt/, /ˈsɛptʃuːəˌdʒɪnt/, from the Latin word septuaginta (meaning seventy), is a translation of the Hebrew Bible and some related texts into Koine Greek. The title and its Roman numeral acronym LXX refer to the legendary seventy Jewish scholars who completed the translation as early as the late 2nd century BCE. As the primary Greek translation of the Old Testament, it is also called the Greek Old Testament (Ἡ μετάφρασις τῶν Ἑβδομήκοντα). This translation is quoted in the New Testament,[1] particularly in the Pauline epistles,[2] and also by the Apostolic Fathers and later Greek Church Fathers.

The traditional story is that Ptolemy II sponsored the translation for use by the many Alexandrian Jews who were not fluent in Hebrew but fluent in Koine Greek,[3] which was the lingua franca of Alexandria, Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean at the time.[4]

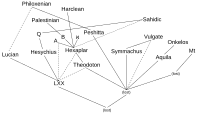

The Septuagint should not be confused with the seven or more other Greek versions of the Old Testament, most of which did not survive except as fragments (some parts of these being known from Origen's Hexapla, a comparison of six translations in adjacent columns, now almost wholly lost). Of these, the most important are those by Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion.

Name

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The Septuagint derives its name from the Latin versio septuaginta interpretum, "translation of the seventy interpreters", Greek: ἡ μετάφρασις τῶν ἑβδομήκοντα, hē metáphrasis tōn hebdomḗkonta, "translation of the seventy".[5] However, it was not until the time of Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) that the Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures came to be called by the Latin term Septuaginta.[6] The Roman numeral LXX (seventy) is commonly used as an abbreviation, as are [7] or G.

Composition

Legend

These titles refer to a legendary story, according to which seventy or seventy-two Jewish scholars were asked (Talmud text implies the scholars were forced) by the Greek King of Egypt Ptolemy II Philadelphus to translate the Torah from Biblical Hebrew into Greek, for inclusion in the Library of Alexandria.[8]

This legend is first found in the pseudepigraphic Letter of Aristeas to his brother Philocrates,[9] and is repeated, with embellishments, by Philo of Alexandria, Josephus[10][11] and by various later sources, including St. Augustine.[12] A version of the legend is found in the Tractate Megillah of the Babylonian Talmud:

King Ptolemy once gathered 72 Elders. He placed them in 72 chambers, each of them in a separate one, without revealing to them why they were summoned. He entered each one's room and said: "Write for me the Torah of Moshe, your teacher". God put it in the heart of each one to translate identically as all the others did.[13]

Philo of Alexandria, who relied extensively on the Septuagint,[14] says that the number of scholars was chosen by selecting six scholars from each of the twelve tribes of Israel.

History

The date of the 3rd century BCE, given in the legend, is supported (for the Torah translation) by a number of factors, including the Greek being representative of early Koine, citations beginning as early as the 2nd century BCE, and early manuscripts datable to the 2nd century.[15][16]

After the Torah, other books were translated over the next two to three centuries. It is not altogether clear which was translated when, or where; some may even have been translated twice, into different versions, and then revised.[17] The quality and style of the different translators also varied considerably from book to book, from the literal to paraphrasing to interpretative.

The translation process of the Septuagint can be broken down into several distinct stages, during which the social milieu of the translators shifted from Hellenistic Judaism to Early Christianity. The translation began in the 3rd century BCE and was completed by 132 BCE,[18][19][20] initially in Alexandria, but in time elsewhere as well.[5]

The Septuagint is the basis for the Old Latin, Slavonic, Syriac, Old Armenian, Old Georgian and Coptic versions of the Christian Old Testament.[21]

Language

Some sections of the Septuagint may show Semiticisms, or idioms and phrases based on Semitic languages like Hebrew and Aramaic.[22] Other books, such as Daniel and Proverbs, show Greek influence more strongly.[8] Jewish Koine Greek exists primarily as a category of literature, or cultural category, but apart from some distinctive religious vocabulary is not so distinct from other varieties of Koine Greek as to be counted a separate dialect.

The Septuagint is also useful for elucidating pre-Masoretic Hebrew: many proper nouns are spelled out with Greek vowels in the LXX, while contemporary Hebrew texts lacked vowel pointing.[23] One must, however, evaluate such evidence with caution since it is extremely unlikely that all ancient Hebrew sounds had precise Greek equivalents.[24]

Disputes over canonicity

As the work of translation progressed, the canon of the Greek Bible expanded. The Torah (Pentateuch in Greek) always maintained its pre-eminence as the basis of the canon, but the collection of prophetic writings, based on the Jewish Nevi'im, had various hagiographical works incorporated into it.

In addition some newer books were included in the Septuagint: those called anagignoskomena in Greek, because they are not included in the Jewish canon. Among these are the Maccabees and the Wisdom of Ben Sira. Also, the Septuagint version of some Biblical books, like Daniel and Esther, are longer than those in the Masoretic Text.[25] Some of these "apocryphal" books (e.g. the Wisdom of Solomon, and the second book of Maccabees) were not translated, but composed directly in Greek.

It is not known when the Ketuvim ("writings"), the final part of the three part Canon was established, although some sort of selective processes must have been employed because the Septuagint did not include other well-known Jewish documents such as Enoch or Jubilees or other writings that are not part of the Jewish canon. (These are now classified as Pseudepigrapha.)

Since Late Antiquity, once attributed to a Council of Jamnia, mainstream rabbinic Judaism rejected the Septuagint as valid Jewish scriptural texts. Several reasons have been given for this. First, some mistranslations were claimed. Second, the Hebrew source texts, in some cases (particularly the Book of Daniel), used for the Septuagint differed from the Masoretic tradition of Hebrew texts, which was chosen as canonical by the Jewish rabbis.[26] Third, the rabbis wanted to distinguish their tradition from the newly emerging tradition of Christianity.[20][27] Finally, the rabbis claimed for the Hebrew language a divine authority, in contrast to Aramaic or Greek—even though these languages were the lingua franca of Jews during this period (Aramaic was eventually given the same holy language status as Hebrew).[28]

In time the LXX became synonymous with the "Greek Old Testament", i.e. a Christian canon of writings which incorporated all the books of the Hebrew canon, along with additional texts. The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches include most of the books that are in the Septuagint in their canons; however, Protestant churches usually do not. After the Protestant Reformation, many Protestant Bibles began to follow the Jewish canon and exclude the additional texts, which came to be called "Apocrypha" (originally meaning "hidden" but became synonymous with "of questionable authenticity"). The Apocrypha are included under a separate heading in the King James Version of the Bible, the basis for the Revised Standard Version.[29]

Final form

- See also Table of books below.

All the books of western canons of the Old Testament are found in the Septuagint, although the order does not always coincide with the Western ordering of the books. The Septuagint order for the Old Testament is evident in the earliest Christian Bibles (4th century).[8]

Some books that are set apart in the Masoretic text are grouped together. For example the Books of Samuel and the Books of Kings are in the LXX one book in four parts called Βασιλειῶν ("Of Reigns"). In LXX, the Books of Chronicles supplement Reigns and it is called Paraleipoménon (Παραλειπομένων—things left out). The Septuagint organizes the minor prophets as twelve parts of one Book of Twelve.[8]

Some scripture of ancient origin are found in the Septuagint but are not present in the Hebrew. These additional books are Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom of Jesus son of Sirach, Baruch, Letter of Jeremiah (which later became chapter 6 of Baruch in the Vulgate), additions to Daniel (The Prayer of Azarias, the Song of the Three Children, Susanna and Bel and the Dragon), additions to Esther, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes, including the Prayer of Manasseh, the Psalms of Solomon, and Psalm 151.

The canonical acceptance of these books varies among different Christian traditions, and there are canonical books not derived from the Septuagint. For more information regarding these books, see the articles Biblical apocrypha, Biblical canon, Books of the Bible, and Deuterocanonical books.

Incorporations from Theodotion

In most ancient copies of the Bible which contain the Septuagint version of the Old Testament, the Book of Daniel is not the original Septuagint version, but instead is a copy of Theodotion's translation from the Hebrew, which more closely resembles the Masoretic text. The Septuagint version was discarded in favour of Theodotion's version in the 2nd to 3rd centuries CE. In Greek-speaking areas, this happened near the end of the 2nd century, and in Latin-speaking areas (at least in North Africa), it occurred in the middle of the 3rd century. History does not record the reason for this, and St. Jerome reports, in the preface to the Vulgate version of Daniel, This thing 'just' happened.[30] One of two Old Greek texts of the Book of Daniel has been recently rediscovered and work is ongoing in reconstructing the original form of the book.[8]

The canonical Ezra-Nehemiah is known in the Septuagint as "Esdras B", and 1 Esdras is "Esdras A". 1 Esdras is a very similar text to the books of Ezra-Nehemiah, and the two are widely thought by scholars to be derived from the same original text. It has been proposed, and is thought highly likely by scholars, that "Esdras B"—the canonical Ezra-Nehemiah—is Theodotion's version of this material, and "Esdras A" is the version which was previously in the Septuagint on its own.[30]

Use

Jewish use

Pre-Christian Jews, Philo and Josephus considered the Septuagint on equal standing with the Hebrew text.[31][32] Manuscripts of the Septuagint have been found among the Qumran Scrolls in the Dead Sea, and were thought to have been in use among Jews at the time.

Starting approximately in the 2nd century CE, several factors led most Jews to abandon use of the LXX. The earliest gentile Christians of necessity used the LXX, as it was at the time the only Greek version of the Bible, and most, if not all, of these early non-Jewish Christians could not read Hebrew. The association of the LXX with a rival religion may have rendered it suspect in the eyes of the newer generation of Jews and Jewish scholars.[21] Instead, Jews used Hebrew/Aramaic Targum manuscripts later compiled by the Masoretes; and authoritative Aramaic translations, such as those of Onkelos and Rabbi Yonathan ben Uziel.[33]

What was perhaps most significant for the LXX, as distinct from other Greek versions, was that the LXX began to lose Jewish sanction after differences between it and contemporary Hebrew scriptures were discovered (see above). Even Greek-speaking Jews tended less to the LXX, preferring other Jewish versions in Greek, such as that of the 2nd-century Aquila translation, which seemed to be more concordant with contemporary Hebrew texts.[21] While Jews have not used the LXX in worship or religious study since the 2nd century CE, recent scholarship has brought renewed interest in it in the field of Judaic Studies.

Christian use

The Early Christian Church used the Greek texts[34] since Greek was a lingua franca of the Roman Empire at the time, and the language of the Greco-Roman Church (Aramaic was the language of Syriac Christianity, which used the Targumim).

The relationship between the apostolic use of the Old Testament, for example, the Septuagint and the now lost Hebrew texts (though to some degree and in some form carried on in Masoretic tradition) is complicated. The Septuagint seems to have been a major source for the Apostles, but it is not the only one. St. Jerome offered, for example, Matt 2:15 and 2:23, John 19:37, John 7:38, 1 Cor. 2:9.[35] as examples not found in the Septuagint, but in Hebrew texts. (Matt 2:23 is not present in current Masoretic tradition either, though according to St. Jerome it was in Isaiah 11:1.) The New Testament writers, when citing the Jewish scriptures, or when quoting Jesus doing so, freely used the Greek translation, implying that Jesus, his Apostles and their followers considered it reliable.[2][22][36]

In the Early Christian Church, the presumption that the Septuagint was translated by Jews before the era of Christ, and that the Septuagint at certain places gives itself more to a christological interpretation than 2nd-century Hebrew texts was taken as evidence that "Jews" had changed the Hebrew text in a way that made them less christological. For example, Irenaeus concerning Isaiah 7:14: The Septuagint clearly writes of a virgin (Greek παρθένος) that shall conceive.[37] While the Hebrew text was, according to Irenaeus, at that time interpreted by Theodotion and Aquila (both proselytes of the Jewish faith) as a young woman that shall conceive. According to Irenaeus, the Ebionites used this to claim that Joseph was the (biological) father of Jesus. From Irenaeus' point of view that was pure heresy, facilitated by (late) anti-Christian alterations of the scripture in Hebrew, as evident by the older, pre-Christian, Septuagint.[38]

When Jerome undertook the revision of the Old Latin translations of the Septuagint, he checked the Septuagint against the Hebrew texts that were then available. He broke with church tradition and translated most of the Old Testament of his Vulgate from Hebrew rather than Greek. His choice was severely criticized by Augustine, his contemporary; a flood of still less moderate criticism came from those who regarded Jerome as a forger. While on the one hand he argued for the superiority of the Hebrew texts in correcting the Septuagint on both philological and theological grounds, on the other, in the context of accusations of heresy against him, Jerome would acknowledge the Septuagint texts as well.[39] With the passage of time, acceptance of Jerome's version gradually increased until it displaced the Old Latin translations of the Septuagint.[21]

The Eastern Orthodox Church still prefers to use the LXX as the basis for translating the Old Testament into other languages. The Eastern Orthodox also use LXX untranslated where Greek is the liturgical language, e.g. in the Orthodox Church of Constantinople, the Church of Greece and the Cypriot Orthodox Church. Critical translations of the Old Testament, while using the Masoretic Text as their basis, consult the Septuagint as well as other versions in an attempt to reconstruct the meaning of the Hebrew text whenever the latter is unclear, undeniably corrupt, or ambiguous.[21] For example, the Jerusalem Bible Foreword says, "... only when this (the Masoretic Text) presents insuperable difficulties have emendations or other versions, such as the ... LXX, been used."[40] The Translator's Preface to the New International Version says: "The translators also consulted the more important early versions (including) the Septuagint ... Readings from these versions were occasionally followed where the MT seemed doubtful ..."[41]

Textual history

Table of books

| The Orthodox Old Testament [5][42][43] |

Greek-based name |

Conventional English name |

| Law | ||

|---|---|---|

| Γένεσις | Génesis | Genesis |

| Ἔξοδος | Éxodos | Exodus |

| Λευϊτικόν | Leuitikón | Leviticus |

| Ἀριθμοί | Arithmoí | Numbers |

| Δευτερονόμιον | Deuteronómion | Deuteronomy |

| History | ||

| Ἰησοῦς Nαυῆ | Iêsous Nauê | Joshua |

| Κριταί | Kritaí | Judges |

| Ῥούθ | Roúth | Ruth |

| Βασιλειῶν Αʹ[44] | I Reigns | I Samuel |

| Βασιλειῶν Βʹ | II Reigns | II Samuel |

| Βασιλειῶν Γʹ | III Reigns | I Kings |

| Βασιλειῶν Δʹ | IV Reigns | II Kings |

| Παραλειπομένων Αʹ | I Paralipomenon[45] | I Chronicles |

| Παραλειπομένων Βʹ | II Paralipomenon | II Chronicles |

| Ἔσδρας Αʹ | I Esdras | 1 Esdras |

| Ἔσδρας Βʹ | II Esdras | Ezra-Nehemiah |

| Τωβίτ[46] | Tobit | Tobit or Tobias |

| Ἰουδίθ | Ioudith | Judith |

| Ἐσθήρ | Esther | Esther with additions |

| Μακκαβαίων Αʹ | I Makkabees | 1 Maccabees |

| Μακκαβαίων Βʹ | II Makkabees | 2 Maccabees |

| Μακκαβαίων Γʹ | III Makkabees | 3 Maccabees |

| Wisdom | ||

| Ψαλμοί | Psalms | Psalms |

| Ψαλμός ΡΝΑʹ | Psalm 151 | Psalm 151 |

| Προσευχὴ Μανασσῆ | Prayer of Manasseh | Prayer of Manasseh |

| Ἰώβ | Iōb | Job |

| Παροιμίαι | Proverbs | Proverbs |

| Ἐκκλησιαστής | Ecclesiastes | Ecclesiastes |

| Ἆσμα Ἀσμάτων | Song of Songs | Song of Solomon or Canticles |

| Σοφία Σαλoμῶντος | Wisdom of Solomon | Wisdom |

| Σοφία Ἰησοῦ Σειράχ | Wisdom of Jesus the son of Seirach | Sirach or Ecclesiasticus |

| Ψαλμοί Σαλoμῶντος | Psalms of Solomon | Psalms of Solomon[47] |

| Prophets | ||

| Δώδεκα | The Twelve | Minor Prophets |

| Ὡσηέ Αʹ | I. Osëe | Hosea |

| Ἀμώς Βʹ | II. Ämōs | Amos |

| Μιχαίας Γʹ | III. Michaias | Micah |

| Ἰωήλ Δʹ | IV. Ioel | Joel |

| Ὀβδιού Εʹ[48] | V. Obdias | Obadiah |

| Ἰωνᾶς Ϛ' | VI. Ionas | Jonah |

| Ναούμ Ζʹ | VII. Naoum | Nahum |

| Ἀμβακούμ Ηʹ | VIII. Ambakum | Habakkuk |

| Σοφονίας Θʹ | IX. Sophonias | Zephaniah |

| Ἀγγαῖος Ιʹ | X. Ängaios | Haggai |

| Ζαχαρίας ΙΑʹ | XI. Zacharias | Zachariah |

| Μαλαχίας ΙΒʹ | XII. Messenger | Malachi |

| Ἠσαΐας | Hesaias | Isaiah |

| Ἱερεμίας | Hieremias | Jeremiah |

| Βαρούχ | Baruch | Baruch |

| Θρῆνοι | Lamentations | Lamentations |

| Ἐπιστολή Ιερεμίου | Epistle of Jeremiah | Letter of Jeremiah |

| Ἰεζεκιήλ | Iezekiêl | Ezekiel |

| Δανιήλ | Daniêl | Daniel with additions |

| Appendix | ||

| Μακκαβαίων Δ' Παράρτημα | IV Makkabees | 4 Maccabees[49] |

Textual analysis

Modern scholarship holds that the LXX was written during the 3rd through 1st centuries BCE. But nearly all attempts at dating specific books, with the exception of the Pentateuch (early- to mid-3rd century BCE), are tentative and without consensus.[8]

Later Jewish revisions and recensions of the Greek against the Hebrew are well attested, the most famous of which include the Three: Aquila (128 CE), Symmachus, and Theodotion. These three, to varying degrees, are more literal renderings of their contemporary Hebrew scriptures as compared to the Old Greek. Modern scholars consider one or more of the 'three' to be totally new Greek versions of the Hebrew Bible.[50]

Around 235 CE, Origen, a Christian scholar in Alexandria, completed the Hexapla, a comprehensive comparison of the ancient versions and Hebrew text side-by-side in six columns, with diacritical markings (a.k.a. "editor's marks", "critical signs" or "Aristarchian signs"). Much of this work was lost, but several compilations of the fragments are available. In the first column was the contemporary Hebrew, in the second a Greek transliteration of it, then the newer Greek versions each in their own columns. Origen also kept a column for the Old Greek (the Septuagint) and next to it was a critical apparatus combining readings from all the Greek versions with diacritical marks indicating to which version each line (Gr. στίχος) belonged.[51] Perhaps the voluminous Hexapla was never copied in its entirety, but Origen's combined text ("the fifth column") was copied frequently, eventually without the editing marks, and the older uncombined text of the LXX was neglected. Thus this combined text became the first major Christian recension of the LXX, often called the Hexaplar recension. In the century following Origen, two other major recensions were identified by Jerome, who attributed these to Lucian and Hesychius.[8]

Manuscripts

The oldest manuscripts of the LXX include 2nd century BCE fragments of Leviticus and Deuteronomy (Rahlfs nos. 801, 819, and 957), and 1st century BCE fragments of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, and the Minor Prophets (Alfred Rahlfs nos. 802, 803, 805, 848, 942, and 943). Relatively complete manuscripts of the LXX postdate the Hexaplar rescension and include the Codex Vaticanus from the 4th century CE and the Codex Alexandrinus of the 5th century. These are indeed the oldest surviving nearly complete manuscripts of the Old Testament in any language; the oldest extant complete Hebrew texts date some 600 years later, from the first half of the 10th century.[21][52] The 4th century Codex Sinaiticus also partially survives, still containing many texts of the Old Testament.[53] While there are differences between these three codices, scholarly consensus today holds that one LXX—that is, the original pre-Christian translation—underlies all three. The various Jewish and later Christian revisions and recensions are largely responsible for the divergence of the codices.[8]

Differences with the Latin Vulgate and the Masoretic text

The sources of the many differences between the Septuagint, the Latin Vulgate and the Masoretic text have long been discussed by scholars. Following the Renaissance, a common opinion among some humanists was that the LXX translators bungled the translation from the Hebrew and that the LXX became more corrupt with time. The most widely accepted view today is that the original Septuagint provided a reasonably accurate record of an early Hebrew textual variant that differed from the ancestor of the Masoretic text as well as those of the Latin Vulgate, where both of the latter seem to have a more similar textual heritage. This view is supported by comparisons with Biblical texts found at the Essene settlement at Qumran (the Dead Sea Scrolls).[citation needed]

These issues notwithstanding, the text of the LXX is generally close to that of the Masoretes and Vulgate. For example, Genesis 4:1–6 is identical in both the LXX, Vulgate and the Masoretic Text. Likewise, Genesis 4:8 to the end of the chapter is the same. There is only one noticeable difference in that chapter, at 4:7, to wit:

| οὐκ ἐὰν ὀρθῶς προσενέγκῃς, ὀρθῶς δὲ μὴ διέλῃς, ἥμαρτες; ἡσύχασον· πρὸς σὲ ἡ ἀποστροφὴ αὐτοῦ, καὶ σὺ ἄρξεις αὐτοῦ. If you offer correctly but do not divide correctly, have you not sinned? Be still; his recourse is to you, and you will rule over him. |

Template:Hebrew Is it not so that if you improve, it will be forgiven you? If you do not improve, however, at the entrance, sin is lying, and to you is its longing, but you can rule over it. |

nonne si bene egeris recipies sin autem male statim in foribus peccatum aderit sed sub te erit appetitus eius et tu dominaberis illius If thou do well, shalt thou not receive? but if ill, shall not sin forthwith be present at the door? but the lust thereof shall be under thee, and thou shalt have dominion over it. |

This instance illustrates the complexity of assessing differences between the LXX and the Masoretic Text as well as the Vulgate. Despite the striking divergence of meaning here between the Septuagint and later texts, nearly identical consonantal Hebrew source texts can be reconstructed. The readily apparent semantic differences result from alternative strategies for interpreting the difficult verse and relate to differences in vowelization and punctuation of the consonantal text.

The differences between the LXX and the MT thus fall into four categories.[54]

- Different Hebrew sources for the MT and the LXX. Evidence of this can be found throughout the Old Testament. Most obvious are major differences in Jeremiah and Job, where the LXX is much shorter and chapters appear in different order than in the MT, and Esther where almost one third of the verses in the LXX text have no parallel in the MT. A more subtle example may be found in Isaiah 36.11; the meaning ultimately remains the same, but the choice of words evidences a different text. The MT reads "...al tedaber yehudit be-'ozne ha`am al ha-homa" [speak not the Judean language in the ears of (or—which can be heard by) the people on the wall]. The same verse in the LXX reads according to the translation of Brenton "and speak not to us in the Jewish tongue: and wherefore speakest thou in the ears of the men on the wall." The MT reads "people" where the LXX reads "men". This difference is very minor and does not affect the meaning of the verse. Scholars at one time had used discrepancies such as this to claim that the LXX was a poor translation of the Hebrew original. With the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, variant Hebrew texts of the Bible were found. In fact this verse is found in Qumran (1QIsaa) where the Hebrew word "haanashim" (the men) is found in place of "haam" (the people). This discovery, and others like it, showed that even seemingly minor differences of translation could be the result of variant Hebrew source texts.

- Differences in interpretation stemming from the same Hebrew text. A good example is Genesis 4.7, shown above.

- Differences as a result of idiomatic translation issues (i.e. a Hebrew idiom may not easily translate into Greek, thus some difference is intentionally or unintentionally imparted). For example, in Psalm 47:10 the MT reads "The shields of the earth belong to God". The LXX reads "To God are the mighty ones of the earth." The metaphor "shields" would not have made much sense to a Greek speaker; thus the words "mighty ones" are substituted in order to retain the original meaning.

- Transmission changes in Hebrew or Greek (Diverging revisionary/recensional changes and copyist errors)

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Biblical manuscripts found in Qumran, commonly known as the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS), have prompted comparisons of the various texts associated with the Hebrew Bible, including the Septuagint.[55] Peter Flint,[56] cites Emanuel Tov, the chief editor of the scrolls,[57] who identifies five broad variation categories of DSS texts:[58]

- Proto-Masoretic: This consists of a stable text and numerous and distinctive agreements with the Masoretic Text. About 60% of the Biblical scrolls fall into this category (e.g. 1QIsa-b)

- Pre-Septuagint: These are the manuscripts which have distinctive affinities with the Greek Bible. These number only about 5% of the Biblical scrolls, for example, 4QDeut-q, 4QSam-a, and 4QJer-b, 4QJer-d. In addition to these manuscripts, several others share distinctive individual readings with the Septuagint, although they do not fall in this category.

- The Qumran "Living Bible": These are the manuscripts which, according to Tov, were copied in accordance with the "Qumran practice" (i.e. with distinctive long orthography and morphology, frequent errors and corrections, and a free approach to the text. Such scrolls comprise about 20% of the Biblical corpus, including the Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsa-a):

- Pre-Samaritan: These are DSS manuscripts which reflect the textual form found in the Samaritan Pentateuch, although the Samaritan Bible itself is later and contains information not found in these earlier scrolls, (e.g. God's holy mountain at Shechem rather than Jerusalem). The Qumran witnesses—which are characterized by orthographic corrections and harmonizations with parallel texts elsewhere in the Pentateuch—comprise about 5% of the Biblical scrolls. (e.g. 4QpaleoExod-m)

- Non-Aligned: This is a category which shows no consistent alignment with any of the other four text-types. These number approximately 10% of the Biblical scrolls, and include 4QDeut-b, 4QDeut-c, 4QDeut-h, 4QIsa-c, and 4QDan-a.[58][59][60]

The textual sources present a variety of readings. For example, Bastiaan Van Elderen [57] compares three variations of Deuteronomy 32:43, the Song of Moses.[citation needed]

|

|

|

The Dead Sea Scrolls, with their 5% connection to the Septuagint, provide significant information for scholars studying the Greek text of the Hebrew Bible.

Printed editions

The texts of all printed editions are derived from the three recensions mentioned above, that of Origen, Lucian, or Hesychius.

- The editio princeps is the Complutensian Polyglot. It was based on manuscripts that are now lost, but seems to transmit quite early readings.[61]

- The Aldine edition (begun by Aldus Manutius) appeared at Venice in 1518. The text is closer to Codex Vaticanus than the Complutensian. The editor says he collated ancient manuscripts but does not specify them. It has been reprinted several times.

- The most important edition is the Roman or Sixtine Septuagint, which uses Codex Vaticanus as the base texts and various other later manuscripts for the lacunae in the uncial manuscript. It was published in 1587 under the direction of Cardinal Antonio Carafa, with the help of a group of Roman scholars (Cardinal Gugliemo Sirleto, Antonio Agelli and Petrus Morinus), by the authority of Sixtus V, to assist the revisers who were preparing the Latin Vulgate edition ordered by the Council of Trent. It has become the textus receptus of the Greek Old Testament and has had many new editions, such as that of Robert Holmes and James Parsons (Oxford, 1798–1827), the seven editions of Constantin von Tischendorf, which appeared at Leipzig between 1850 and 1887, the last two, published after the death of the author and revised by Nestle, the four editions of Henry Barclay Swete (Cambridge, 1887–95, 1901, 1909), etc. A detailed description of this edition has been made by H. B. Swete in his An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek (1900), pp. 174–182.

- Grabe's edition was published at Oxford, from 1707 to 1720, and reproduced, but imperfectly, the Codex Alexandrinus of London. For partial editions, see Fulcran Vigouroux, Dictionnaire de la Bible, 1643 sqq.

- Alfred Rahlfs, a longtime Septuagint researcher at Göttingen, began a manual edition of the Septuagint in 1917 or 1918. The completed Septuaginta was published in 1935. It relies mainly on Vaticanus, Sinaiticus, and Alexandrinus, and presents a critical apparatus with variants from these and several other sources.[62]

- The Göttingen Septuagint (Vetus Testamentum Graecum: Auctoritate Academiae Scientiarum Gottingensis editum) is a major critical version, comprising multiple volumes published from 1931 to 2009 and not yet complete (the largest missing parts are the history books Joshua through Chronicles except Ruth, and the Solomonic books Proverbs through Song of Songs). Its two critical apparatuses present variant Septuagint readings and variants from other Greek versions.[63]

- In 2006, a revision of Alfred Rahlfs's Septuaginta was published by the German Bible Society. This editio altera includes over a thousand changes to the text and apparatus.[64]

- Apostolic Bible Polyglot contains a Septuagint text derived mainly from the agreement of any two of the Complutensian Polyglot, the Sixtine, and the Aldine texts.[65]

English translations

The Septuagint has been translated surprisingly few times into English. The first one, which excluded the Apocrypha, was Charles Thomson's in 1808, which was subsequently revised and enlarged by C.A. Muses in 1954.

The translation of Sir Lancelot C. L. Brenton, published in 1851, is a long-time standard. For most of the years since its publication it has been the only one readily available, and has continually been in print. It is based primarily upon the Codex Vaticanus and contains the Greek and English texts in parallel columns. There is also a revision of the Brenton Septuagint available through Stauros Ministries, called The Complete Apostles' Bible, translated by Paul W. Esposito, Th.D, and released in 2007. [2]

The International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies (IOSCS) has produced A New English Translation of the Septuagint and the Other Greek Translations Traditionally Included Under that Title (NETS), an academic translation based on standard critical editions of the Greek texts. It was published by Oxford University Press in October 2007.

The Apostolic Bible Polyglot, published in 2003, includes the Greek books of the Hebrew canon along with the Greek New Testament, all numerically coded to the AB-Strong numbering system, and set in monotonic orthography. Included in the printed edition is a concordance and index.

The Orthodox Study Bible was released in early 2008 with a new translation of the Septuagint based on the Alfred Rahlfs edition of the Greek text. To this base they brought two additional major sources: first the Brenton translation of the Septuagint from 1851, and, second, Thomas Nelson Publishers granted use of the New King James Version text in the places where the translation of the LXX would match that of the Hebrew Masoretic text. This edition includes the New Testament as well, which also uses the New King James Version; and it includes, further, extensive commentary from an Eastern Orthodox perspective.[66]

The Eastern / Greek Orthodox Bible (EOB) is an extensive revision and correction of Brenton’s translation which was primarily based on Codex Vaticanus. Its language and syntax have been modernized and simplified. It also includes extensive introductory material and footnotes featuring significant inter-LXX and LXX/MT variants.

Father Nicholas King, SJ, a Jesuit priest who lectures in New Testament Studies at Oxford University, has completed a four volume translation of the Septuagint, begun in 2010 and finished in 2013; and available from Kevin Mayhew Publishers, entitled The Old Testament (volumes 1 through 4).[3] It contains a very useful mini commentary on each book which gives a flavor of what is hoped to be the start of accessible, reasonably priced individual commentaries for the general reader.

The most comprehensive English edition is quite possibly[citation needed] that of Gary F. Zeolla, entitled Analytical Literal Translation of The Old Testament (Septuagint) (ALT). Four volumes have already been published,[4] and the fifth and final volume on the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical books is expected from LuLu Publishers in 2015. It is a word-for-word literal translation, rather than a dynamic equivalence, or sectarian translation. Like the NETS it has every 'Septuagintal' Book, rather than slavishly following the Hebrew canon as a template, which makes for completeness. An advantage for the beginner in using Zeolla's edition is that it can be compared with the original Greek, or any[citation needed] English translation of the Hebrew OT, to see the variations between the versions.

Promotion

The International Organization for Septuagint and Cognate Studies (IOSCS), a nonprofit, learned society formed to promote international research in and study of the Septuagint and related texts,[67] has established February 8 annually as International Septuagint Day, a day to promote the discipline on campuses and in communities. The Organization is also publishing the "Journal of Septuagint and Cognate Studies" (JSCS).

See also

- Brenton's English Translation of the Septuagint

- Alfred Rahlfs—editor of a commonly distributed critical edition of LXX.

- La Bible d'Alexandrie

- Documentary hypothesis—discusses the theoretical recensional history of the Torah/Pentateuch in Hebrew.

- Tanakh at Qumran—some of the Dead Sea Scrolls are witnesses to the LXX text.

- Septuagint manuscripts

- Vulgate

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

- Hellenistic Judaism

References

- ^ "The quotations from the Old Testament found in the New are in the main taken from the Septuagint; and even where the citation is indirect the influence of this version is clearly seen.""Bible Translations – The Septuagint". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ a b "His quotations from Scripture, which are all taken, directly or from memory, from the Greek version, betray no familiarity with the original Hebrew text (..) Nor is there any indication in Paul's writings or arguments that he had received the rabbinical training ascribed to him by Christian writers (..)""Paul, the Apostle of the Heathen". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "[T]he Egyptian papyri, which are abundant for this particular period, ... have in a measure reinstated Aristeas (about 200 B.C.) in the opinion of scholars. Upon his "Letter to Philocrates" the tradition as to the origin of the Septuagint rests. It is now believed that even though he may have been mistaken in some points, his facts in general are worthy of credence (Abrahams, in "Jew. Quart. Rev." xiv. 321). According to Aristeas, the Pentateuch was translated at the time of Philadelphus, the second Ptolemy (285–247 B.C.), which translation was encouraged by the king and welcomed by the Jews of Alexandria. Grätz ("Gesch. der Juden", 3d ed., iii. 615) stands alone in assigning it to the reign of Philometor (181–146 B.C.). Whatever share the king may have had in the work, it evidently satisfied a pressing need felt by the Jewish community, among whom a knowledge of Hebrew was rapidly waning before the demands of every-day life.""Bible Translations – The Septuagint". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Hellenism: Range of Hellenic Influence: "Except in Egypt, Hellenic influence was nowhere stronger than on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean. Greek cities arose there in continuation, or in place, of the older Semitic foundations, and gradually changed the aspect of the country."

- ^ a b c Karen H. Jobes and Moises Silva (2001). Invitation to the Septuagint. Paternoster Press. ISBN 1-84227-061-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sundberg, in McDonald & Sanders, eds., The Canon Debate, p.72. See Augustine, The City of God, 18.42, where Augustine says that "this name ["Septuaginta"] has now become traditional", indicating that this was a recent event. But Augustine offers no clue as to which of the possible antecedents led to this development.

- ^ Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, for instance.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jennifer M. Dines, The Septuagint, Michael A. Knibb, Ed., London: T&T Clark, 2004.

- ^ Davila, J (2008). "Aristeas to Philocrates". Summary of lecture by Davila, February 11, 1999. University of St. Andrews, School of Divinity. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ Flavius Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ William Whiston (1998). The Complete Works of Josephus. T. Nelson Publishers. ISBN 0-7852-1426-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Augustine of Hippo, The City of God 18.42.

- ^ Tractate Megillah, pages 9a-9b. The Talmud identifies fifteen specific unusual translations made by the scholars, but only two of these translations are found in the extant LXX.

- ^ "(..) Philo bases his citations from the Bible on the Septuagint version, though he has no scruple about modifying them or citing them with much freedom. Josephus follows this translation closely.""Bible Translations – The Septuagint". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ J.A.L. Lee, A Lexical Study of the Septuagint Version of the Pentateuch (Septuagint and Cognate Studies, 14. Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1983; Reprint SBL, 2006)

- ^ http://books.google.ru/books?id=Qv8Riv3QIbQC&pg=PA35&lpg=PA35&dq=aristobulus+septuagint&source=bl&ots=J0xfL9cmhi&sig=LkUPY1vVLzfD_Dfspyc29XKaOMU&hl=en&sa=X&ei=iqz2U_LLHJDR4QSe5oH4Dw&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=aristobulus%20septuagint&f=false

- ^ Joel Kalvesmaki, The Septuagint

- ^ Life after death: a history of the afterlife in the religions of the West (2004), Anchor Bible Reference Library, Alan F. Segal, p.363

- ^ Gilles Dorival, Marguerite Harl, and Olivier Munnich, La Bible grecque des Septante: Du judaïsme hellénistique au christianisme ancien (Paris: Cerfs, 1988), p.111

- ^ a b "[...] die griechische Bibelübersetzung, die einem innerjüdischen Bedürfnis entsprang [...] [von den] Rabbinern zuerst gerühmt (..) Später jedoch, als manche ungenaue Übertragung des hebräischen Textes in der Septuaginta und Übersetzungsfehler die Grundlage für hellenistische Irrlehren abgaben, lehnte man die Septuaginta ab." Verband der Deutschen Juden (Hrsg.), neu hrsg. von Walter Homolka, Walter Jacob, Tovia Ben Chorin: Die Lehren des Judentums nach den Quellen; München, Knesebeck, 1999, Bd.3, S. 43ff

- ^ a b c d e f Ernst Würthwein, The Text of the Old Testament, trans. Errol F. Rhodes, Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. Eerdmans, 1995.

- ^ a b H. B. Swete, An Introduction to the Old Testament in Greek, revised by R.R. Ottley, 1914; reprint, Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1989.

- ^ Hoffman, Book Review, 2004.

- ^ Paul Joüon, SJ, A Grammar of Biblical Hebrew, trans. and revised by T. Muraoka, vol. I, Rome: Editrice Pontificio Instituto Biblico, 2000.

- ^ Rick Grant Jones, Various Religious Topics, "Books of the Septuagint", (Accessed 2006.9.5).

- ^ "The translation, which shows at times a peculiar ignorance of Hebrew usage, was evidently made from a codex which differed widely in places from the text crystallized by the Masorah." "Bible Translations – The Septuagint". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Two things, however, rendered the Septuagint unwelcome in the long run to the Jews. Its divergence from the accepted text (afterward called the Masoretic) was too evident; and it therefore could not serve as a basis for theological discussion or for homiletic interpretation. This distrust was accentuated by the fact that it had been adopted as Sacred Scripture by the new faith [Christianity] [...] In course of time it came to be the canonical Greek Bible [...] It became part of the Bible of the Christian Church.""Bible Translations – The Septuagint". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Mishnah Sotah (7:2–4 and 8:1), among many others, discusses the sacredness of Hebrew, as opposed to Aramaic or Greek. This is comparable to the authority claimed for the original Arabic Koran according to Islamic teaching. As a result of this teaching, translations of the Torah into Koine Greek by early Jewish Rabbis have survived as rare fragments only.

- ^ "NETS: Electronic Edition". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. 2011-02-11. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ a b This article incorporates text from the 1903 Encyclopaedia Biblica article "TEXT AND VERSIONS", a publication now in the public domain.

- ^ J.M. Dines, The Septuagint (2005)

- ^ Alexander Zvielli, Jerusalem Post, June 2009, pp. 37

- ^ Greek-speaking Judaism (see also Hellenistic Judaism), survived, however, on a smaller scale into the medieval period. Cf. Natalio Fernández Marcos, The Septuagint in Context: Introduction to the Greek Bible, Leiden: Brill, 2000.

- ^ "The translation, which shows at times a peculiar ignorance of Hebrew usage, was evidently made from a codex which differed widely in places from the text crystallized by the Masorah (..) Two things, however, rendered the Septuagint unwelcome in the long run to the Jews. Its divergence from the accepted text (afterward called the Masoretic) was too evident; and it therefore could not serve as a basis for theological discussion or for homiletic interpretation. This distrust was accentuated by the fact that it had been adopted as Sacred Scripture by the new faith [Christianity] (..) In course of time it came to be the canonical Greek Bible (..) It became part of the Bible of the Christian Church.""Bible Translations – The Septuagint". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ St. Jerome, Apology Book II.

- ^ "The quotations from the Old Testament found in the New are in the main taken from the Septuagint; and even where the citation is indirect the influence of this version is clearly seen (..)""Bible Translations – The Septuagint". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Paulkovich, Michael (2012), No Meek Messiah, Spillix Publishing, p. 24, ISBN 0988216116

- ^ Irenaeus, Against Herecies Book III.

- ^ Rebenich, S., Jerome (Routledge, 2013), p. 58. ISBN 9781134638444

- ^ Jerusalem Bible Readers Edition, 1990: London, citing the Standard Edition of 1985

- ^ "Life Application Bible" (NIV), 1988: Tyndale House Publishers, using "Holy Bible" text, copyright International Bible Society 1973

- ^ Timothy McLay, The Use of the Septuagint in New Testament Research ISBN 0-8028-6091-5.—The current standard introduction on the NT & LXX.

- ^ The canon of the original Old Greek LXX is disputed. This table reflects the canon of the Old Testament as used currently in Orthodoxy.

- ^ Βασιλειῶν (Basileiōn) is the genitive plural of Βασιλεῖα (Basileia).

- ^ That is, Things set aside from Ἔσδρας Αʹ.

- ^ also called Τωβείτ or Τωβίθ in some sources.

- ^ Not in Orthodox Canon, but originally included in the LXX. http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/nets/edition/

- ^ Obdiou is genitive from "The vision of Obdias", which opens the book.

- ^ Originally placed after 3 Maccabees and before Psalms, but placed in an appendix of the Orthodox Canon

- ^ Compare Dines, who is certain only of Symmachus being a truly new version, with Würthwein, who considers only Theodotion to be a revision, and even then possibly of an earlier non-LXX version.

- ^ Jerome, From Jerome, Letter LXXI (404 CE), NPNF1-01. The Confessions and Letters of St. Augustin, with a Sketch of his Life and Work, Phillip Schaff, Ed.

- ^ Due to the practice of burying Torah scrolls invalidated for use by age, commonly after 300–400 years.

- ^ Würthwein, op. cit., pp. 73 & 198.

- ^ See, Jinbachian, Some Semantically Significant Differences Between the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint, [1].

- ^ "Searching for the Better Text – Biblical Archaeology Society". Bib-arch.org. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ Dr. Peter Flint. Curriculum Vitae. Trinity Western University. Langley, BC, Canada. Accessed March 26, 2011

- ^ a b Edwin Yamauchi, "Bastiaan Van Elderen, 1924– 2004", SBL Forum Accessed March 26, 2011.

- ^ a b Tov, E. 2001. Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible (2nd ed.) Assen/Maastricht: Van Gocum; Philadelphia: Fortress Press. As cited in Flint, Peter W. 2002. The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls as presented in Bible and computer: the Stellenbosch AIBI-6 Conference: proceedings of the Association internationale Bible et informatique, "From alpha to byte", University of Stellenbosch, 17–21 July, 2000 Association internationale Bible et informatique. Conference, Johann Cook (ed.) Leiden/Boston BRILL, 2002

- ^ Laurence Shiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, p. 172

- ^ Note that these percentages are disputed. Other scholars credit the Proto-Masoretic texts with only 40%, and posit larger contributions from Qumran-style and non-aligned texts. The Canon Debate, McDonald & Sanders editors, 2002, chapter 6: Questions of Canon through the Dead Sea Scrolls by James C. VanderKam, page 94, citing private communication with Emanuel Tov on biblical manuscripts: Qumran scribe type c.25%, proto-Masoretic Text c. 40%, pre-Samaritan texts c.5%, texts close to the Hebrew model for the Septuagint c.5% and nonaligned c.25%.

- ^ Joseph Ziegler, "Der griechische Dodekepropheton-Text der Complutenser Polyglotte", Biblica 25:297–310, cited in Würthwein.

- ^ Rahlfs, A. (Ed.). (1935/1979). Septuaginta. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft.

- ^ IOSCS: Critical Editions of Septuagint/Old Greek Texts

- ^ German Bible Society shop

- ^ Introduction to the Apostolic Bible

- ^ "Conciliar Press". Orthodox Study Bible. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ "IOSCS". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

Further reading

- Timothy Michael Law, When God Spoke Greek, Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Eberhard Bons and Jan Joosten, eds. Septuagint Vocabulary: Pre-History, Usage, Reception (Society of Biblical Literature; 2011) 211 pages; studies of the language used

- Kantor, Mattis, The Jewish time line encyclopedia: A yearby-year history from Creation to the present, Jason Aronson Inc., London, 1992

- Alfred Rahlfs, Verzeichnis der griechischen Handschriften des Alten Testaments, für das Septuaginta-Unternehmen, Göttingen 1914.

- Makrakis, Apostolos, Proofs of the Authenticity of the Septuagint, trans. by D. Cummings, Chicago, Ill.: Hellenic Christian Educational Society, 1947. N.B.: Published and printed with its own pagination, whether as issued separately or as included together with 2 other works of A. Makrakis in a single volume published by the same film in 1950, wherein the translator's name is identified on the common t.p. to that volume.

- W. Emery Barnes, On the Influence of Septuagint on the Peshitta, JTS 1901, pp. 186–197.

- Andreas Juckel, Septuaginta and Peshitta Jacob of Edessa quoting the Old Testament in Ms BL Add 17134 JOURNAL OF SYRIAC STUDIES

- Martin Hengel, The Septuagint As Christian Scripture, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004.

- Rajak, Tessa, Translation and survival: the Greek Bible of the ancient Jewish Diaspora (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Bart D. Ehrman. The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings; 608 pages, Oxford University Press (July, 2011); ISBN 978-0-19-975753-4

- Hyam Maccoby. The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity; 238 pages, Barnes & Noble Books (1998); ISBN 978-0-7607-0787-6

External links

General

- The Septuagint Sessions – A podcast on the Septuagint and related literature

- The Septuagint Online – Comprehensive site with scholarly discussion and links to texts and translations

- The Septuagint Institute

- Jewish Encyclopedia (1906): Bible Translations

- Catholic Encyclopedia (1913): Septuagint Version

- Catholic Encyclopedia (1913): Versions of the Bible

- Searching for the Better Text: How errors crept into the Bible and what can be done to correct them (Biblical Archaeology Review)

- Codex: Resources and Links Relating to the Septuagint

- Extensive chronological and canonical list of Early Papyri and Manuscripts of the Septuagint

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Texts and translations

- The Old Testament, by Nicholas King, in four volumes. Kevin Mayhew Publishers. Analytical Translation of The Old Testament(Septuagint), by Gary F. Zeolla, 4 volumes with fifth and final volume on the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books to be published in 2015 by LuLu Publishers. A complete work with literal word for word translation.

- Septuagint/Old Greek Texts and Translations LXX finder, listing dozens of editions, both print and digital, in various languages and formats. A good place to start.

- Septuagint and New Testament – Despite its name, this site does not in fact provide the LXX, rather a shortened version which eliminates all the LXX books later called "deuterocanonical". The Greek NT is presented in full. Both Greek texts, the (incomplete) LXX and the NT, have parsing and concordance.

- Elpenor's Bilingual (Greek / English) Septuagint Old Testament Greek text (full polytonic unicode version) and English translation side by side. Greek text as used by the Orthodox Churches.

- Titus Text Collection: Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interpretes (advanced research tool)

- Septuagint published by the Church of Greece

- Plain text of the whole LXX

- Greek-English interlinear of OT & NT. Monotonic orthography.

- Bible Resource Pages – contains Septuagint texts (with diacritics) side-by-side with English translations

- The Septuagint in Greek as an MS Word document (requires Vusillus Old Face (Error in Webarchive template: Empty url.). Introduction and book abbreviations in Latin.)

- The Book of Daniel from an Old Greek LXX[dead link] (no diacritics, needs special font)

- Sir Lancelot C.L. Brenton's translation

- The New English Translation of the Septuagint (NETS), electronic edition

- Project to produce an Orthodox Study Bible (OSB) whose Old Testament is based entirely on the Septuagint.[dead link]

- EOB: Eastern / Greek Orthodox Bible: includes comprehensive introductory materials dealing with Septuagintal issues and an Old Testament which is an extensive revision of the Brenton with footnotes.

- The Septuagint LXX in English (Online text of the entire LXX English translation by Sir Lancelot Brenton)

- The Holy Orthodox Bible translated by Peter A. Papoutsis from the Septuagint (LXX) and the Official Greek New Testament text of the Ecumenical Patriarch.

- Septuagint LXX – The Septuaginta LXX is an on-going Septuagint project that aims to produce an online critical text of the Septuagint with a comprehensive critical apparatus, and English translation of the Septuagint, Aquila, Theodotion, and Symmachus.

- LXX2012: Septuagint in American English 2012 – The Septuagint with Apocrypha, translated from Greek to English by Sir Lancelot C. L. Brenton and published in 1885, with some language updates by Michael Paul Johnson in 2012 (American English)

- LXX2012: Septuagint in British/International English 2012 – The Septuagint with Apocrypha, translated from Greek to English by Sir Lancelot C. L. Brenton and published in 1885, with some language updates by Michael Paul Johnson in 2012 (British/International English)

The LXX and the NT

- Septuagint references in NT by John Salza

- An Apology for the Septuagint – by Edward William Grinfield