Commodore 64

| |

| Type | Home computer |

|---|---|

| Release date | August 1982[1][2] |

| Introductory price | US $595 (approx. $1,900 today) |

| Discontinued | April 1994 |

| Units sold | 12.5[3] – 17[4] million |

| Operating system | Commodore KERNAL/ Commodore BASIC 2.0 GEOS (optionally) |

| CPU | MOS Technology 6510 @ 1.023 MHz (NTSC version) @ 0.985 MHz (PAL version) |

| Memory | 64 kB RAM + 20 kB ROM |

| Graphics | VIC-II (320 × 200, 16 colors, sprites, raster interrupt) |

| Sound | SID 6581 (3× osc, 4× wave, filter, ADSR, ring) |

| Connectivity | 2× CIA 6526 joystick, Power, ROM cartridge, RF, A/V, IEEE-488 floppy-printer, digital tape, GPIO/RS-232 |

| Predecessor | Commodore VIC-20 |

| Successor | Commodore 128 |

The Commodore 64, also known as the C64, C-64, C=64, or occasionally CBM 64 or VIC-64,[5] is an 8-bit home computer introduced in January, 1982 by Commodore International. It is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the highest-selling single computer model of all time,[6] with independent estimates placing the number sold between 10 and 17 million units.[7]

Volume production started in early 1982, with machines being released on to the market in August at a price of US $595 (roughly equivalent to $1,900 in 2023).[8][9] Preceded by the Commodore VIC-20 and Commodore PET, the C64 takes its name from its 64 kilobytes (65,536 bytes) of RAM, and has favorable sound and graphical specifications when compared to contemporary systems such as the Apple II. While the Apple cost around $1,200, it was sold as a complete system with disk drive and dedicated monitor—the C64's $595 price included only the computer itself. The Tandy TRS-80 Color Computer was initially priced at $399, but had only 4kB RAM and could not match the C64's graphics and sound abilities.

The C64 dominated the low-end computer market for most of the 1980s.[10] For a substantial period (1983–1986), the C64 had between 30% and 40% share and two million units sold per year,[11] outselling the IBM PC compatibles, Apple Inc. computers, and the Atari 8-bit family of computers. Sam Tramiel, a later Atari president and the son of Commodore's founder, said in a 1989 interview, "When I was at Commodore we were building 400,000 C64s a month for a couple of years."[12]

Part of the Commodore 64's success was because it was sold in retail stores instead of just electronics- and/or computer stores. Commodore produced many of its parts in-house to control costs, including custom IC chips from MOS Technology. It is sometimes compared to the Ford Model T automobile for its role in bringing a new technology to middle-class households via creative mass-production.[13]

Approximately 10.000 commercial software titles were made for the Commodore 64 including development tools, office productivity applications, and games.[14] C64 emulators allow anyone with a modern computer, or a compatible video game console, to run these programs today. The C64 is also credited with popularizing the computer demoscene and is still used today by some computer hobbyists.[15] In 2008, 17 years after it was taken off the market, research showed that brand recognition for the model was still at 87%.[6]

History

In January 1981, MOS Technology, Inc., Commodore's integrated circuit design subsidiary, initiated a project to design the graphic and audio chips for a next generation video game console. Design work for the chips, named MOS Technology VIC-II (Video Integrated Circuit for graphics) and MOS Technology SID (Sound Interface Device for audio), was completed in November 1981.[8]

Commodore then began a game console project that would use the new chips—called the Ultimax or alternatively the Commodore MAX Machine, engineered by Yash Terakura from Commodore Japan. This project was eventually cancelled after just a few machines were manufactured for the Japanese market.

At the same time, Robert "Bob" Russell (system programmer and architect on the VIC-20) and Robert "Bob" Yannes (engineer of the SID) were critical of the current product line-up at Commodore, which was a continuation of the Commodore PET line aimed at business users. With the support of Al Charpentier (engineer of the VIC-II) and Charles Winterble (manager of MOS Technology), they proposed to Commodore CEO Jack Tramiel a true low-cost sequel to the VIC-20. Tramiel dictated that the machine should have 64 kB of random-access memory (RAM). Although 64 kB of dynamic random access memory (DRAM) cost over $100 at the time, he knew that DRAM prices were falling, and would drop to an acceptable level before full production was reached. In November, Tramiel set a deadline for the first weekend of January, to coincide with the 1982 Consumer Electronics Show (CES).[8]

The product was code named the VIC-40 as the successor to the popular VIC-20. The team that constructed it consisted of Bob Russell, Bob Yannes and David A. Ziembicki. The design, prototypes and some sample software were finished in time for the show, after the team had worked tirelessly over both Thanksgiving and Christmas weekends.

The machine incorporated Commodore BASIC 2.0 in ROM. BASIC also served as the user interface shell and was available immediately on startup at the READY prompt.

When the product was to be presented, the VIC-40 product was renamed C64 to fit the contemporary Commodore business products lineup which contained the P128 and the B256, both named by a letter and their respective total memory size (in KBytes).

The C64 made an impressive debut at the January 1982 Consumer Electronics Show, as recalled by Production Engineer David A. Ziembicki: "All we saw at our booth were Atari people with their mouths dropping open, saying, 'How can you do that for $595?'" The answer, as it turned out, was vertical integration; thanks to Commodore's ownership of MOS Technology's semiconductor fabrication facilities, each C64 had an estimated production cost of only $135.

Winning the market war

The C64 faced a wide range of competing home computers at its introduction in August 1982.[2] With a lower price and more flexible hardware, it quickly outsold many of its competitors. In the United States the greatest competitors were the Atari 8-bit 400 and 800, and the Apple II. The Atari 400 and 800 had been designed to accommodate previously stringent FCC emissions requirements and so were expensive to manufacture. The latest revision in the aging Apple II line, the Apple IIe, had higher-resolution graphics modes than the C64.[16][17] Upgrade capability for the Apple II was granted by internal expansion slots, while the C64 had only a single external ROM cartridge port for bus expansion. However, the Apple used its expansion slots for interfacing to common peripherals like disk drives, printers and modems; the C64 had a variety of ports integrated into its motherboard which were used for these purposes, usually leaving the cartridge port free.

All four machines had similar standard memory configurations in the years 1982/83: 48K for the Apple II+[18] (upgraded within months of C64's release to 64K with the Apple IIe) and 48K for the Atari 800.[19] At upwards of $1,200,[20] the Apple II was about twice as expensive, while the Atari 800 cost $899. One key to the C64's success was Commodore's aggressive marketing tactics, and they were quick to exploit the relative price/performance divisions between its competitors with a series of television commercials after the C64's launch in late 1982.[21] The company also published detailed documentation to help developers,[22] while Atari initially kept technical information secret.[23] At a mid-1984 conference of game developers and experts at Origins Game Fair, Dan Bunten, Sid Meier ("the computer of choice right now"), and a representative of Avalon Hill all stated that they were developing games for the 64 first as the most promising market.[24] In April 1986 Computer Gaming World published a survey of ten game publishers which found that they planned to release forty-three Commodore 64 games that year, compared to nineteen for Atari and forty-eight for Apple II,[25] and that year Alan Miller stated that Accolade developed first for the C64 because "it will sell the most on that system".[26]

Commodore sold the C64 not only through its network of authorized dealers, but also through department stores, discount stores, toy stores and college bookstores. The C64 had a built-in RF modulator and thus could be plugged into a television set. This allowed it (like its predecessor, the VIC-20) to compete directly against video game consoles such as the Atari 2600. Like the Apple IIe, the C64 could also output baseband composite video and thus could be plugged into a specialized monitor for a sharper picture. Unlike the IIe, the C64's baseband NTSC output capability included separate luminance/chroma signal output equivalent to (and electrically compatible with) S-Video, for connection to the Commodore 1702 monitor.

Aggressive pricing of the C64 is considered to be a major catalyst in the North American video game crash of 1983. In January 1983, Commodore offered a $100 rebate in the United States on the purchase of a C64 to anyone trading in another video game console or computer.[27] To take advantage of this rebate, some mail-order dealers and retailers offered a Timex Sinclair 1000 for as little as $10 with purchase of a C64, so the consumer could send the TS1000 to Commodore, collect the rebate, and pocket the difference; Timex Corporation departed the computer market within a year. Commodore's tactics soon led to a price war with the major home computer manufacturers. The success of the VIC-20 and C64 contributed significantly to the exit of Texas Instruments and other smaller competitors from the field. The price war with Texas Instruments was seen as a personal battle for Commodore president Jack Tramiel;[28] TI's subsequent demise in the home computer industry in October 1983 was seen as revenge for TI's tactics in the electronic calculator market in the mid-1970s, when Commodore was almost bankrupted by TI.[29] Computer Gaming World stated in January 1985 that companies such as Epyx that survived the video game crash did so because they "jumped on the Commodore bandwagon early".[30]

In Europe, the primary competitors to the C64 were the British-built Sinclair ZX Spectrum, BBC Micro computer and the Amstrad CPC 464. In the UK, the Spectrum had been released a few months ahead of the C64, and was selling for less than half the price. The Spectrum quickly became the market leader and Commodore had an uphill struggle against the Spectrum. The C64 debuted at £399 in early 1983, while the 48K Spectrum cost £175. The C64 went on to rival the Spectrum in popularity in the latter half of the 1980s. Adjusted to the size of population the popularity of Commodore 64 was the highest in Finland where it was subsequently marketed as "the computer of the republic".[31]

By mid-1986 Commodore had sold 3.5 million C64s, with about one million sold in 1985. Although the company reportedly attempted to discontinue the C64 more than once in favor of more expensive computers such as the 128, demand remained strong.[32][33] That year Commodore introduced the 64c, a redesigned 64, which Compute! saw as evidence that—contrary to C64 owners' fears that the company would abandon them in favor of the Amiga and 128—"the 64 refuses to die".[34] Its introduction also meant that Commodore raised the price of the C64 for the first time, which the magazine cited as the end of the home-computer price war.[35] Software sales also remained strong; MicroProse, for example, in 1987 cited the Commodore and IBM PC markets as its top priorities.[36]

By 1988, Commodore was still selling 1.5 million C64s worldwide,[37] although Epyx CEO David Shannon Morse cautioned that "there are no new 64 buyers, or very few. It's a consistent group that's not growing ... it's going to shrink as part of our business".[38] One computer-gaming executive stated that the Nintendo Entertainment System's enormous popularity—seven million sold that year, almost as many as the number of C64s sold in its first five years—had stopped the C64's growth, and Trip Hawkins stated that Nintendo was "the last hurrah of the 8-bit world".[39] Although demand for the C64 dropped off in the United States by 1990, it continued to be popular in the UK and other European countries. In the end, economics, not obsolescence, sealed the C64's fate. In March 1994, at CeBIT in Hanover, Germany, Commodore announced that the C64 would be finally discontinued in 1995.[40] Commodore stated that the C64's disk drive was more expensive to manufacture than the C64 itself.[40] However, only one month later, in April 1994, the company filed for bankruptcy.

The C64 family

1982: Commodore released the Commodore MAX Machine in Japan. It is called the Ultimax in the United States, and VC-10 in Germany. The MAX was intended to be a game console with limited computing capability, and was based on a very cut-down version of the hardware family later used in the C64. The MAX was discontinued months after its introduction, because of poor sales in Japan.

1983 saw Commodore attempt to compete with the Apple II's hold on the U.S. education market with the Educator 64,[41] essentially a C64 and "greenscale" monochrome monitor in a PET case. Schools preferred the all-in-one metal construction of the PET over the standard C64's separate components, which could be easily damaged, vandalized or stolen.[42] Schools did not prefer the Educator 64 to the wide range of software and hardware options the Apple IIe was able to offer, and it was produced in limited quantities.[43]

In 1984, Commodore released the SX-64, a portable version of the C64. The SX-64 has the distinction of being the first full-color portable computer. While earlier computers using this form factor only incorporated monochrome "green screen" displays, the base SX-64 unit featured a 5 in (130 mm) color cathode ray tube (CRT) and an integrated 1541 floppy disk drive. The SX-64 did not have a cassette connector.

Also in 1984, Commodore released the Commodore Plus/4. It had a higher-color display, a newer implementation of Commodore BASIC (V3.5), and built-in software in what was positioned as an inexpensive business oriented system. However, it was incompatible with the C64, and the burgeoning influence of the IBM PC on the personal computer market market rendered the limited business software of the Plus/4 system of marginal value. The Plus/4 lacked hardware sprite capability and lacked a SID chip, thus under-performing in two of the areas that had made the C64 successful.

Two designers at Commodore, Fred Bowen and Bil Herd, were determined to rectify the problems of the Plus/4. They intended that the eventual successors to the C64—the Commodore 128 and 128D computers (1985)—were to build upon the C64, avoiding the Plus/4's flaws.[44] The successors had many improvements (such as a structured BASIC with graphics and sound commands, 80-column display ability, and full CP/M compatibility). The decision to make the Commodore 128 plug compatible with the C64 was made quietly by Bowen and Herd, software and hardware designers respectively, without the knowledge or approval by the management in the post Jack Tramiel era. The designers were careful not to reveal their decision until the project was too far along to be challenged or changed and still make the impending Consumer Electronics Show (CES) show in Las Vegas.[44] Upon learning that the C128 was designed to be compatible with the C64, Commodore's marketing department independently announced that the C128 would be 100% compatible with the C64, thereby raising the bar for C64 support.[45] In a case of malicious compliance, the 128 design was altered to include a separate "64 mode" using a complete C64 environment to ensure total compatibility.

In 1986, Commodore released the Commodore 64c computer, which was functionally identical to the original. The exterior design was remodeled in the sleeker style of the Commodore 128.[33] The modifications to the C64 line were more than skin deep in the 64c with new versions of the SID, VIC and I/O chips being deployed—with the core voltage reduced from 12V to 9V. In the United States, the 64c was often bundled with the third-party GEOS graphical user interface (GUI) based operating system. The Commodore 1541 disk drive received a matching face-lift resulting in the 1541c. Later a smaller, sleeker 1541-II model was introduced along with the 800 kB 3.5-inch microfloppy 1581.

In 1990, the C64 was rereleased in the form of a game console, called the C64 Games System (C64GS). A simple modification to the C64C's motherboard was made to orient the cartridge connector to a vertical position. This allowed cartridges to be inserted from above. A modified ROM replaced the BASIC interpreter with a boot screen to inform the user to insert a cartridge. Designed to compete with the Nintendo Entertainment System and the Sega Master System, it suffered from very low sales compared to its rivals. It was another commercial failure for Commodore, and it was never released outside of Europe.

In 1990, an advanced successor to the C64, the Commodore 65 (also known as the "C64DX"), was prototyped, but the project was canceled by Commodore's chairman Irving Gould in 1991. The C65's specifications were very good for an 8-bit computer, bringing specs comparable to the Apple IIgs. For example, it could display 256 colors on screen, while OCS based Amigas could only display 64 in HalfBrite mode (32 colors and half-bright transformations). Although no specific reason was given for the C65's cancellation, it would have competed in the marketplace with Commodore's lower end Amigas and the Commodore CDTV.

C64 clones

In the middle of 2004, after an absence from the marketplace of more than 10 years, PC manufacturer Tulip Computers BV (owners of the Commodore brand since 1997) announced the C64 Direct-to-TV (C64DTV), a joystick-based TV game based on the C64 with 30 games built into ROM. Designed by Jeri Ellsworth, a self-taught computer designer who had earlier designed the modern C-One C64 implementation, the C64DTV was similar in concept to other mini-consoles based on the Atari 2600 and Intellivision which had gained modest success earlier in the decade. The product was advertised on QVC in the United States for the 2004 holiday season. Some users have installed 1541 floppy disk drives, hard drives, second joysticks and keyboards to these units, which give the DTV devices nearly all of the capabilities of a full Commodore 64. The DTV hardware is also used in the mini-console/game Hummer, sold at RadioShack mid-2005.

C64 enthusiasts still develop new hardware, including Ethernet cards,[46] specially adapted hard disks and flash card interfaces (sd2iec).[47]

Brand re-use

In 1998, the C64 brand was reused for the "Web.it Internet Computer",[48][49] a low-powered (even for the time) Internet-oriented, all-in-one x86 PC running Windows 3.1. Despite its "Commodore 64" nameplate, the "C64 Web.it" was not directly compatible with the original (except via included emulation software), nor did it share its appearance.

PC clones branded as C64x sold by Commodore USA, LLC, a company licensing the Commodore trademark,[50][51] began shipping in June 2011.[52][53] The C64x has a case resembling the original C64 computer, but- as with the "Web.it"- it is based on x86 architecture and is not compatible with the Commodore 64 on either hardware or software level.

Virtual Console

Several Commodore 64 games were released on the Nintendo Wii's Virtual Console service in Europe and North America only. The games were removed from the service as of August 2013 for unknown reasons.

Software

In 1982, the C64's graphics and sound capabilities were rivaled only by the Atari 8-bit family, and appeared exceptional when compared with the widely publicised Atari VCS and Apple II.

The C64 is often credited with starting the computer subculture known as the demoscene (see Commodore 64 demos). It is still being actively used in the demoscene,[54] especially for music (its sound chip even being used in special sound cards for PCs, and the Elektron SidStation synthesizer). Unfortunately, the differences between PAL and NTSC C64s caused compatibility problems between U.S./Canadian C64s and those from most other countries. The vast majority of demos run only on PAL machines.

Even though other computers quickly caught up with it, the C64 remained a strong competitor to the later video game consoles Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) and Sega Master System, thanks in part to its by-then established software base, especially outside of North America, where it comprehensively outsold the NES.[citation needed]

BASIC

As was common for home computers of the early 1980s, the C64 incorporated a ROM-based version of the BASIC programming language. There was no operating system as such. The KERNAL was accessed via BASIC commands. The disk drive had its own microprocessor, much like the Atari 800. This meant that no memory space had to be dedicated to running a disk operating system, as remained the case with earlier systems such as the Apple II.

Commodore BASIC 2.0 was used instead of the more advanced BASIC 4.0 from the PET series, since 64 users were not expected to need the disk-oriented enhancements of BASIC 4.0. The company did not expect many to buy a disk drive, and using BASIC 2.0 simplified VIC-20 owners' transition to the 64.[55] "The choice of BASIC 2.0 instead of 4.0 was made with some soul-searching, not just at random. The typical user of a C64 is not expected to need the direct disk commands as much as other extensions and the amount of memory to be committed to BASIC were to be limited. We chose to leave expansion space for color and sound extensions instead of the disk features. As a result, you will have to handle the disk in the more cumbersome manner of the 'old days'."[56]

The version of BASIC was limited and did not include specific commands for sound or graphics manipulation, instead required users to use the "POKE" commands to access the graphics and sound chip registers directly. To provide extended commands, including graphics and sound, Commodore produced two different cartridge-based extension to BASIC 2.0 — Simons' BASIC and Super Expander 64.

Other languages available for the C64 included Pascal, Logo, Forth, and FORTRAN. Compiled versions of BASIC such as Petspeed 2 (from Commodore) and Turbo Lightning (Ocean Software) were also available. While the first generation of C64 software may have used one of these or even the standard BASIC, after 1983 almost all professionally produced programs were written in assembly language, using a machine code monitor or an assembler. This maximised speed and minimised memory use.

Alternative operating systems

Many third party operating systems have been developed for the C64. As well as the original GEOS, two third-party GEOS-compatible systems have been written: Wheels and GEOS megapatch. Both of these require hardware upgrades to the original C64. Several other operating systems are or have been available, including WiNGS OS, the Unix-like LUnix, operated from a command-line, and the embedded systems OS Contiki, with full GUI. Other less well known OSes include ACE, Asterix, DOS/65 and GeckOS.

A version of CP/M was released, but this required the addition of an external Z80 processor to the expansion bus, so is not considered a true C64 OS. Furthermore, the Z80 processor was underclocked to be compatible with the C64's memory bus, so performance was poor compared to other CP/M implementations. C64 CP/M and C128 CP/M both suffered a lack of software: although most commercial CP/M software could run on these systems, software media was incompatible between platforms. The low usage of CP/M on Commodores meant that software houses saw no need to invest in mastering versions for the Commodore disk format.

Networking software

During the 1980s, the Commodore 64 was used to run many bulletin board systems using software packages such as Bizarre 64, Blue Board, C-Net, Color 64, CMBBS, C-Base, DMBBS, Image BBS, and The Deadlock Deluxe BBS Construction Kit, often with sysop-made modifications. These boards sometimes were used to distribute cracked software. As late as December 2013, there were 25 such Bulletin Board Systems in operation, reachable via the Telnet protocol.[citation needed]. In an attempt to address the need for a citation, a list of Commodore BBS systems currently in operation, along with others that are known to be offline is maintained by hobbyists and can be seen at http://cbbsoutpost.servebbs.com [57]

There were also major commercial online services, such as Compunet (UK), CompuServe (US – later bought by America Online), The Source (US) and Minitel (France) among many others. These services usually required custom software which was often bundled with a modem and included free online time as they were billed by the minute.

Quantum Link (or Q-Link) was a U.S. and Canadian online service for Commodore 64 and 128 personal computers that operated from November 5, 1985, to November 1, 1994. It was operated by Quantum Computer Services of Vienna, Virginia, which in October 1991 changed its name to America Online, and continues to operate its AOL service for the IBM PC compatible and Apple Macintosh today. Q-Link was a modified version of the PlayNET system, which Control Video Corporation (CVC, later renamed Quantum Computer Services) licensed.

Online gaming

The first graphical character-based interactive environment was Club Caribe. First released as Habitat in 1988, Club Caribe was introduced by LucasArts for Q-Link customers on their Commodore 64 computers. Users could interact with one another, chat and exchange items. Although the game's open world was very basic, its use of online avatars (already well-established off-line by Ultima and other games) and combination of chat and graphics was revolutionary. Online graphics in the late 1980s were severely restricted by the need to support modem data transfer rates as slow as 300 bits per second (bit/s). Habitat's graphics were stored locally on floppy disk, eliminating the need for network transfer. Along with these games some new gaming engines were created in the process. The game Maniac Mansion made by LucasArts needed its own unique engine named SCUMM to be played. The engine is somewhat of a mix of a programming language and a gaming engine. LucasArts eventually used the gaming engine for other games they released.

Hardware

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (April 2010) |

CPU and memory

The C64 uses an 8-bit MOS Technology 6510 microprocessor. This is a close derivative of the 6502 with an added 6-bit internal I/O port that in the C64 is used for two purposes: to bank-switch the machine's read-only memory (ROM) in and out of the processor's address space, and to operate the datasette tape recorder.

The C64 has 64 kB of RAM, of which 38 kB are available to built-in Commodore BASIC 2.0 on startup.

There is 20 kB of ROM, made up of the BASIC interpreter, the kernel, and the character ROM. As the processor could only address 64 kB at a time, the ROM was mapped into memory and only 38,911 bytes of RAM were available at startup.

If a program did not use the BASIC interpreter, RAM could be mapped over the ROM locations. However, this meant the character ROM would not be available, and the RAM in its place was instead used for the character glyphs. Normally, this RAM was uninitialised, which would then result in nothing but random patterns appearing on the screen. This was solved by copying the character ROM into RAM. This had two benefits – the standard typeface could be rewritten, and character codes could be rewritten as picture elements.

Most C64 games were written in this way, using low resolution, which required much less processor time and saved memory. Furthermore, picture elements could be reused, saving even more precious memory. The same technique was used on the NES.

Graphics

The graphics chip, VIC-II, features 16 colors, eight hardware sprites per scanline (enabling up to 112 sprites per PAL screen), scrolling capabilities, and two bitmap graphics modes. The standard text mode features 40 columns, like most Commodore PET models; the built in character encoding is not standard ASCII but PETSCII, an extended form of ASCII-1963.

Most screenshots show borders around the screen, which is a feature of the VIC-II chip. By utilising interrupts to reset various hardware registers on precise timings it was possible to place graphics within the borders and thus utilise the full screen.[58]

There were two low-resolution and two bitmapped modes. Multicolor bitmapped mode had an addressable screen of 160 × 200 pixels, with a maximum of four colors per 4 × 8 character block. High-resolution bitmapped mode had an addressable screen of 320 × 200 pixels, with a maximum of two colors per 8 × 8 character block.

Multicolor low-resolution had a screen of 160 × 200 pixels, 40 × 25 addressable with four colors per 8 × 8 character block; high resolution "low resolution" had a screen of 320 × 200 pixels, 40 × 25 addressable with two colors per 8 × 8 character block. Most video games were multicolor low-resolution; this allowed only block-by-block character animation due to the limited addressable space. However, further innovation allowed video chips to automate sprites and vertical and horizontal scrolling pixel-by-pixel, allowing graphics to work smoothly and quickly regardless of the video mode. Some animation, like bullets, used character animation when sprites were unavailable.

Sound

The SID chip has three channels, each with its own ADSR envelope generator, ring modulation and filter capabilities. Bob Yannes developed the SID chip and later co-founded synthesizer company Ensoniq. Yannes criticized other contemporary computer sound chips as "primitive, obviously...designed by people who knew nothing about music". Often the game music became a hit of its own among C64 users. Well-known composers and programmers of game music on the C64 are Rob Hubbard, David Whittaker, Chris Hülsbeck, Ben Daglish, Martin Galway and David Dunn among many others. Due to the chip's three channels, chords are played as arpeggios, coining the C64's characteristic lively sound. It was also possible to continuously update the master volume with sampled data to enable the playback of 4-bit digitized audio. As of 2008, it became possible to play four channel 8-bit audio samples, 2 SID channels and still use filtering.[59]

There are two versions of the SID chip, the 6581 and the 8580. The MOS Technology 6581 was used in the original "breadbox" C64s, the early versions of the C64C and the Commodore 128. The 6581 was replaced with the MOS Technology 8580 in 1987. The 6581 sound quality is a little crisper, and many Commodore 64 fans prefer its sound. The main difference between the 6581 and the 8580 is the supply voltage. The 6581 uses a 12 volt supply—the 8580, a 9 volt supply. A modification can be made to use the 6581 in a C64C board (which uses the 9 volt chip).

The SID chip has a distinctive sound which has retained a following of devotees to such a degree, that a number of audio enthusiasts and companies have designed SID-based products as add-ons for the C64, x86 PCs, and standalone or MIDI music devices such as the Elektron SidStation. These devices use chips taken from excess stock, or removed from used computers.

In 2007, Timbaland's extensive use of the SidStation led to the plagiarism controversy for "Block Party" and "Do It" (written for Nelly Furtado).

Hardware revisions

Cost reduction was the driving force behind the C64's motherboard revisions. Reducing manufacturing costs was vitally important to Commodore's survival during the price war and leaner years of the 16-bit era. The C64's original (NMOS based) motherboard would go through two major redesigns, (and numerous sub-revisions) exchanging positions of the VIC-II, SID and PLA chips. Initially, a large portion of the cost was eliminated by reducing the number of discrete components, such as diodes and resistors, which enabled the use of a smaller printed circuit board.

The case is made from ABS plastic which may become brown with time. This can be reversed by using the public domain chemical mix "Retr0bright".

ICs

The VIC-II was manufactured with 5 micrometer NMOS technology[8] and was clocked at either 17.73447 MHz (PAL) or 14.31818 MHz (NTSC). Internally, the clock was divided down to generate the dot clock (about 8 MHz) and the two-phase system clocks (about 1 MHz; the exact pixel and system clock speeds are slightly different between NTSC and PAL machines). At such high clock rates, the chip generated a lot of heat, forcing MOS Technology to use a ceramic dual in-line package called a "CERDIP". The ceramic package was more expensive, but it dissipated heat more effectively than plastic.

After a redesign in 1983, the VIC-II was encased in a plastic dual in-line package, which reduced costs substantially, but it did not totally eliminate the heat problem.[8] Without a ceramic package, the VIC-II required the use of a heat sink. To avoid extra cost, the metal RF shielding doubled as the heat sink for the VIC, although not all units shipped with this type of shielding. Most C64s in Europe shipped with a cardboard RF shield, coated with a layer of metal foil. The effectiveness of the cardboard was highly questionable, and worse still it acted as an insulator, blocking airflow which trapped heat generated by the SID, VIC, and PLA chips.

The SID was manufactured using NMOS at 7 and in some areas 6 micrometers.[8] The prototype SID and some very early production models featured a ceramic dual in-line package, but unlike the VIC-II, these are extremely rare as the SID was encased in plastic when production started in early 1982.

Motherboard

In 1986, Commodore released the last revision to the classic C64 motherboard. It was otherwise identical to the 1984 design, except for the two 64 kilobit × 4 bit DRAM chips that replaced the original eight 64 kilobit × 1 bit ICs.

After the release of the C64C, MOS Technology began to reconfigure the C64's chipset to use HMOS production technology. The main benefit of using HMOS was that it required less voltage to drive the IC, which consequently generates less heat. This enhanced the overall reliability of the SID and VIC-II. The new chipset was renumbered to 85xx to reflect the change to HMOS.

In 1987, Commodore released C64Cs with a highly redesigned motherboard commonly known as a "short board". The new board used the new HMOS chipset, featuring a new 64-pin PLA chip. The new "SuperPLA", as it was dubbed, integrated many discrete components and transistor–transistor logic (TTL) chips. In the last revision of the C64C motherboard, the 2114 color RAM was integrated into the SuperPLA.

Power supply

The C64 used an external power supply, a conventional transformer with multiple tappings (as opposed to switch mode, the type now used on PC power supplies), encased in an epoxy resin gel which discouraged tampering but tended to increase the heat level during use.

This saved space within the computer's case and allowed international versions to be more easily manufactured. The 1541-II and 1581 disk drives, along with various third-party clones, also came with their own external power supply "bricks", as did most peripherals leading to a "spaghetti" of cables and the use of numerous double adapters by users. These power supplies were notorious for failing over time,[60] usually because of overheating.

Commodore later changed the design, omitting the gel. The follow-on model, the Commodore 128, used a larger, improved power supply that included a fuse.

Specifications

Internal hardware

- Microprocessor CPU:

- MOS Technology 6510/8500 (the 6510/8500 is a modified 6502 with an integrated 6-bit I/O port)

- Clock speed: 0.985 MHz (PAL) or 1.023 MHz (NTSC)

- Video: MOS Technology VIC-II 6567/8562 (NTSC), 6569/8565 (PAL)

- 16 colors

- Text mode: 40×25 characters; 256 user-defined chars (8×8 pixels, or 4×8 in multicolor mode); 4-bit color RAM defines foreground color

- Bitmap modes: 320×200 (2 unique colors in each 8×8 pixel block),[61] 160×200 (3 unique colors + 1 common color in each 4×8 block)[62]

- 8 hardware sprites of 24×21 pixels (12×21 in multicolor mode)

- Smooth scrolling, raster interrupts

- Sound: MOS Technology 6581/8580 SID

- 3-channel synthesizer with programmable ADSR envelope

- 8 octaves

- 4 waveforms per audio channel: triangle, sawtooth, variable pulse, noise

- Oscillator synchronization, ring modulation

- Programmable filter: high pass, low pass, band pass, notch filter

- Input/Output: Two 6526 Complex Interface Adapters

- 16 bit parallel I/O

- 8 bit serial I/O

- 24-hours (AM/PM) Time of Day clock (TOD), with programmable alarm clock[63]

- 16 bit interval timers

- RAM:

- 64 kB, of which 38 kB (minus 1 byte) were available for BASIC programs

- 512 bytes color RAM (memory allocated for screen color data storage) [64]

- Expandable to 320 kB with Commodore 1764 256 kB RAM Expansion Unit (REU); although only 64 kB directly accessible; REU mostly intended for GEOS. REUs of 128 kB and 512 kB, originally designed for the C128, were also available, but required the user to buy a stronger power supply from some third party supplier; with the 1764 this was included. Creative Micro Designs also produced a 2 MB REU for the C64 and C128, called the 1750 XL. The technology actually supported up to 16 MB, but 2 MB was the biggest one officially made. Expansions of up to 16 MB were also possible via the CMD SuperCPU.

- ROM:

- 20 kB (9 kB Commodore BASIC 2.0; 7 kB KERNAL; 4 kB character generator, providing two 2 kB character sets)

I/O ports and power supply

- I/O ports:[65]

- ROM cartridge expansion slot (44-pin slot for edge connector with 6510 CPU address/data bus lines and control signals, as well as GND and voltage pins;[66] used for program modules and memory expansions, among others)

- Integrated RF modulator antenna output via a RCA connector. The used channel could be adjusted from number 36 with the potentiometer to the left.

- 8-pin DIN connector containing composite video output, separate Y/C outputs and sound input/output. Beware that this is the 262° (horseshoe) version of the plug, not the 270° circular version. Also note that some early C64 units use a 5-pin DIN connector that carries composite video and luminance signals, but lacks a chroma signal.[67]

- Serial bus (serial version of IEEE-488, 6-pin DIN plug) for CBM printers and disk drives

- PET-type Commodore Datassette 300 baud tape interface (edge connector with digital cassette motor/read/write/key-sense signals, Ground and +5V DC lines. The cassette motor is controlled by a +5V DC signal from the 6502 CPU. The 9V AC input is transformed into unregulated 6.36V DC[68] which is used to actually power the cassette motor.[69]

- User port (edge connector with TTL-level signals, for modems and so on.; byte-parallel signals which can be used to drive third-party parallel printers, among other things, 17 logic signals, 7 Ground and voltage pins, including 9V AC)

- 2 × screwless DE9M game controller ports (compatible with Atari 2600 controllers), each supporting five digital inputs and two analog inputs. Available peripherals included digital joysticks, analog paddles, a light pen, the Commodore 1351 mouse, and graphics tablets such as the KoalaPad.

- Power supply:

The 9 volt AC is used to supply power via a charge pump to the SID sound generator chip, provide 6.8V via a rectifier to the cassette motor, a "0" pulse for every positive half wave to the time-of-day (TOD) input on the CIA chips, and 9 volts AC directly to the user-port. Thus, as a minimum, a 12 V square wave is required. But a 9 V sine wave is preferred.[71][72]

Memory map

| Address | Size [kB] |

Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x0000 | 32.0 | RAM | [73] | ||

| 0x8000 | 8.0 | RAM | Cartridge ROM | [73] | |

| 0xA000 | 8.0 | RAM | Basic ROM | [73] | |

| 0xC000 | 4.0 | RAM | [73] | ||

| 0xD000 | 4.0 | RAM | I/O | Character ROM | [73] |

| 0xE000 | 8.0 | RAM | KERNAL ROM | [73] | |

Note that even if I/O chips like VIC-II only uses 64 positions in the memory address space, it will occupy 1,024 addresses because some address bits are left undecoded.[73]

Peripherals

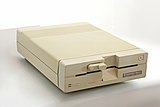

-

Commodore 1541 Floppy Drive, 1st model.

-

Commodore 1541C Floppy Drive, 2nd model.

-

Commodore 1541-II Floppy Drive, 3rd model.

-

Commodore 1530 Datasette

-

Commodore MPS-802 Dot matrix printer

-

Commodore VIC-Modem

-

Commodore 1702 video monitor

Response

BYTE in July 1983 stated that "the 64 retails for $595. At that price it promises to be one of the hottest contenders in the under-$1000 personal computer market". It described SID as "a true music synthesizer...the quality of the sound has to be heard to be believed", while criticizing the use of Commodore BASIC 2.0, the slow disk access ("even slower than the Atari 810 drive"), and Commodore's quality control.[74]

See also

- Commodore SX-64 – Portable version

- History of personal computers

- Commodore 64 peripherals

- List of Commodore 64 games

- Commodore 64 demos

- Commodore MAX Machine – the Commodore 64's predecessor

- Commodore 128 – the Commodore 64's descendant

- C-One – Programmable FPGA clone

- C64 Direct-to-TV – ASIC clone with 30 built in games

- IDE64 – P-ATA interface cartridge for the C64

- SuperCPU - CPU upgrade for C64 and C128

Footnotes

- ^ World of Commodore Brochure (1983)

- ^ a b July 1982 Commodore brochure

- ^ "How many Commodore 64 computers were sold?". Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy. "Personal Computer Market Share: 1975–2004". Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ VIC 64 Användarmanual. Image of Swedish edition of the VIC 64 user's manual. Retrieved on 2007-03-12.

- ^ a b http://www.cnn.com/2011/TECH/gaming.gadgets/05/09/commodore.64.reborn/

- ^ "How many Commodore 64 computers were really sold?".

- ^ a b c d e f Perry, Tekla S.; Wallich, Paul (March 1985). "Design case history: the Commodore 64" (PDF). IEEE Spectrum: 48–58. ISSN 0018-9235. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|laysummary=, and|laysource=(help) - ^ "MayhemUK Commodore 64 archive". 090918 mayhem64.co.uk

- ^ http://www.pcworld.com/article/152528/comm64.html

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy. "Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ^ Naman, Mard (September 1989). "From Atari's Oval Office An Exclusive Interview With Atari President Sam Tramiel". STart. 4 (2). San Francisco: Antic Publishing: p. 16.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Kahney, Leander (9 September 2003). "Grandiose Price for a Modest PC". CondéNet, Inc. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "Impact of the Commodore 64: A 25th Anniversary Celebration". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ Swenson, Reid C. (2007). "What is a Commodore Computer? A Look at the Incredible History and Legacy of the Commodore Home Computers". OldSoftware.Com. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ "PC – Model 5150". old-computers.com. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "Apple IIe". old-computers.com. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "Apple II+". old-computers.com. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "Atari 800". old-computers.com. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "Apple II History Chap 6"

- ^ "Commodore Commercials". commodorebillboard.de. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ Gupta, Anu M. (June 1983). "Commodore 64 Programmer's Reference Guide". Compute! (review). p. 134. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ Tomczyk, Michael S. (1984). The Home Computer Wars: An Insider's Account of Commodore and Jack Tramiel. Compute! Publications. p. 110. ISBN 0942386787.

- ^ "The CGW Computer Game Conference". Computer Gaming World (panel discussion). October 1984. p. 30.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Survey of Game Manufacturers". Computer Gaming World. April 1986. p. 32.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Boosman, Frank (November 1986). "Designer Profiles / Alan Miller". Computer Gaming World (interview). p. 6.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Protecto Enterprise (June 1983). "Commodore computer advertisement". Popular Mechanics. 159 (6). Hearst Magazines: p. 140. ISSN 0032-4558.

We pack with your computer a voucher good for $100 rebate from the factory when you send in your old Atari, Mattel, Coleco electronic game or computer …

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Nocera, Joseph (April 1984). "Death of a Computer". Texas Monthly. 12 (4). Austin, Texas: Emmis Communications: pp. 136-139, 216–226. ISSN 0148-7736.

Once before, Commodore had put out a product in a market where it chief competitor was TI: a line of digital watches. TI started a price war and drove Commodore out of the market. Tramiel was not about to let that happen again.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Remier, Jeremy. "A history of the Amiga, part 4: Enter Commodore". arstechnica.com. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ Jacobs, Bob (January 1985). "An Agent Looks at the Software Industry". Computer Gaming World. p. 18.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Yle: Ohjelmat". 20 November 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Halfhill, Tom R. (April 1986). "A Turning Point For Atari?". Compute!. p. 30. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ a b Wagner, Roy (August 1986). "The Commodore Key". Computer Gaming World. p. 28.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lock, Robert; Halfhill, Tom R. (July 1986). "Editor's Notes". Compute!. p. 6. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leemon, Sheldon (February 1987). "Microfocus". Compute!. p. 24. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Brooks, M. Evan (November 1987). "Titans of the Computer Gaming World / MicroProse". Computer Gaming World. p. 16.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Computer Chronicles: Interview with Commodore president with Max Toy". 2007-07-24. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Ferrell, Keith; Keizer, Gregg (September 1988). "Epyx Grows with David Morse". Compute!. p. 10. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ferrell, Keith (July 1989). "Just Kids' Play or Computer in Disguise?". Compute!. p. 28. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ^ a b Amiga Format News Special. "Commodore at CeBIT '94". Amiga Format, Issue 59, May 1994.

- ^ "The Educator 64 & Commodore PET 64 (aka C=4064)". zimmers.net. Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "The 4064s: PET 64, Educator 64".

School officials were dismayed at how easily the breadbox units could be stolen (in fact, quite a few disappeared from schools, and they fit very neatly in students' knapsacks), so Commodore presented the old PET cases as an inexpensive stopgap solution.

- ^ http://www.floodgap.com/retrobits/ckb/secret/4064.html

- ^ a b http://www.kirps.com/web/main/_blog/all/in-memory-of-the-commodore-c128.shtml

- ^ Mace, Scott (January 28, 1985). "Commodore Shows New 128". InfoWorld. 7 (4). Menlo Park, CA: Popular Computing: pp. 19–20. ISSN 0199-6649.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Dunkels, Adam. "The Final Ethernet – C64 Ethernet Cartridge". Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "SD2IEC on c64 wiki".

- ^ "C64, C128 - Teil 2 - Retroport". retroport.de. 2013-06-14. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ^ "Commodore 64: Web.It". amigahistory.co.uk. 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ^ "Iconic Commodore 64 All Set For Comeback".

- ^ "Recreating the Legendary Commodore 64".

- ^ "Commodore USA begins shipping replica C64s next week, fulfilling your beige breadbox dreams".

- ^ "Commodore USA site showing assembly and boxed units ready for shipping".

- ^ "C=4 Expo 2008". Lyonlabs.org. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ Heimarck, Todd (1987-06). "When 2 + 3.5 + 4 = 7 / The Evolution of Commodore BASIC". Compute!'s Gazette. pp. 20–26. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "C64 Basic Introduction", Commodore Magazine, August 1982, p. 65.

- ^ http://cbbsoutpost.servebbs.com

- ^ Ojala, Pasi. "Opening the Borders". Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "New revolutionary C64 music routine unveiled". C64Music!. 2008. Retrieved 2014-05-20.

- ^ Mace, Scott (November 13, 1983). "Commodore 64: Many unhappy returns". InfoWorld. 5 (46). Popular Computing Inc.: p. 23. ISSN 0199-6649.

{{cite journal}}:|page=has extra text (help) - ^ Rautiainen, Sami. "Programmers_Reference". Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ Rautiainen, Sami. "Programmers_Reference". Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- ^ MOS 6526 CIA datasheet (PDF format)

- ^ Rautiainen, Sami. "Service_Manual: RAM Control Logic". Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ^ "empty". 090505 computermuseum.li

- ^ The Hardware Book

- ^ Carlsen, Ray. "C64 video port". Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ^ "250469 rev.A right". 100610 zimmers.net

- ^ "250469 rev.A left". 100610 zimmers.net

- ^ "Commodore C64 Power Supply Connector Pinout – AllPinouts". 090505 allpinouts.org

- ^ "Commodore-64 BN/E 250469 schematic". 090519 zimmers.net

- ^ "Commodore-64 BN/E 250469 schematic". 090519 zimmers.net

- ^ a b c d e f g "Commodore 64 memory map". sta.c64.org. 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- ^ Wszola, Stan (July 1983). "Commodore 64". BYTE. p. 232. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

References

- Angerhausen, M.; Becker, Dr. A.; Englisch, L.; Gerits, K. (1983, 84). The Anatomy of the Commodore 64. Abacus Software (US ed.) / First Publishing Ltd. (UK ed.). ISBN 0-948015-00-4 (UK ed.). German original edition published by Data Becker GmbH & Co. KG, Düsseldorf.

- Bagnall, Brian (2005). On the Edge: the Spectacular Rise and Fall of Commodore. Variant Press. ISBN 0-9738649-0-7. See especially pp. 224–260.

- Commodore Business Machines, Inc., Computer Systems Division (1982). Commodore 64 Programmer's Reference Guide. Self-published by CBM. ISBN 0-672-22056-3.

- Tomczyk, Michael (1984). The Home Computer Wars: An Insider's Account of Commodore and Jack Tramiel. COMPUTE! Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-942386-75-2.

- Jeffries, Ron. "A best buy for '83: Commodore 64". Creative Computing, January 1983.

- Amiga Format News Special. "Commodore at CeBIT '94". Amiga Format, Issue 59, May 1994.

- Computer Chronicles; "Commodore 64 – Interview with Commodore president Max Toy", 1988.

- The C-64 Scene Database; "– Kjell Nordbø artist page (bio/release history) at CSDb".

- Michael Steil (2008-12-29). The Ultimate Commodore 64 Talk. 25th Chaos Communication Congress (25c3). Berlin. Retrieved 2013-12-28.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)

External links

- C64 Preservation Project Discusses preservation of classic software for the Commodore 64

- Template:Dmoz

- The History of the Commodore 64

- C64.com The home of Commodore 64 software and interviews with many game producers

- Commodore 64 history, manuals, and photos

- Extensive collection of information on C64 programming

- A History of Gaming Platforms: The Commodore 64 from October 2007

- Images of the C64 prototype from 2003

- A Commodore 64 Web Server Using Contiki v2.3

- Commodore 8-bit web links Project 70 sites and counting

- Commodore 64 Search Engine + Cloud

- "Commodore 64 still loved after all these years", CNN

- "The Commodore 64 at 25: thank you for the music", The Guardian

- Review of 5 different Commodore 64 models/motherboards, MOS6502.com

- Commodore Computer Club Discusses hardware, software, repairs and the scene for the Commodore 64

- "How to use the Commodore 64 for chiptunes", 2D-X

- Archived 2010-05-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Commodore 64 turns 30: What do today's kids make of it?, BBC

- Design case history: the Commodore 64, IEEE Spectrum, March 1985