Logophoricity

Template:Parenthetical referencing editnotice

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

The term logophor was introduced by Claude Hagège (1974) in order to distinguish logophoric pronouns from indirect reflexive pronouns. In particular, Hagège argues that logophors are a distinct class of pronouns which refer to the source of indirect discourse: the individual whose perspective is being communicated, rather than the speaker who is relaying this information. George N. Clements (1975) expanded upon this analysis, arguing that indirect reflexives serve the same function as logophoric pronouns, even though indirect reflexives do not exhibit a distinct form from their non-logophoric counterparts, whereas logophoric pronouns (as Hagège defined them) do (Reuland 2006, p. 3). For example, the Latin indirect reflexive pronoun sibi may be said to have two grammatical functions (logophoric and reflexive), but just one form (Clements 1975). More recent analyses of logophoricity are in line with this account, under which indirect reflexives are considered to be logophors, in addition to those pronouns with a special logophoric form (Reuland 2006, p. 3).

Clements also extended the concept of logophoricity beyond Hagège's initial typology, addressing syntactic and semantic properties of logophoric pronouns, as well. (Reuland 2006, p. 3). He posited three distinctive properties of logophors:

- Logophoric pronouns are discourse-bound: they may only occur in a context in which the perspective of an individual other than the speaker's is being reported.

- The antecedent of the logophoric pronoun must not occur in the same clause in which the indirect speech is introduced.

- The antecdent specifies which individual's (or individuals') perspective is being reported.

These conditions are for the most part semantic in nature, though Clements also claimed that there are additional syntactic factors which may play a role when semantic conditions are not met, yet logophoric pronouns are still present. In Ewe, for example, logophoric pronouns may only occur in clauses which are headed by the complementizer "be" (which designates a reportive context in this language), and may only have a second- or third-person antecedent (first-person antecedents are prohibited). Other languages impose different conditions on the occurrence of logophors, which leads Clements to conclude that there are no universal syntactic constraints which must be satisfied by logophoric forms.

Logophoric Typology

Logophoric Affixes

The simplest form of a logophoric affix is a system called logophoric cross referencing. This is when a distinct affix is used to specify logophoric cases (Curnow 2002). For example in Akɔɔse, a language spoken in Nigeria, the prefix mə attaches to the verb to indicate that the pronoun is self-referencing.

a. à-hɔbé ǎ á-kàg he-said RP he-should.go 'He said that he (someone else) should go' b. à-hɔbé ǎ mə-kàg he-said RP LOG-should.go 'He said that he (himself) should go' (Hedinger 1984:95)

It is important to note that not all cross-referencing utilizes the same properties. In Akɔɔse, cross-referencing can only occur when the matrix subject is second or third person singular, not in plural or first person cases (Curnow 2002); however, any language that uses a logophoric cross-referencing system will always use it for singular referents. (Curnow 2002:4)

Another manifestation of logophoric affixes is the logophoric verbal affix, or a logophoric affix that attaches to the verb. Unlike logophoric pronouns and the cross-referencing system, the logophoric verbal suffix is not otherwise integrated into a system that marks person (Curnow 2002:11). In contrast with cross-referencing, verbal affixes are not obligatory for singular second person referents. Unlike most other types of logophoricity, verbal affixes may also be used in first person case, where generally this use is unpreferred. The verbal affix may also lead to ambiguity unlike most other types of logophoricity, as since it attaches to the verb and not to the subject, or a co-referring pronoun, it only indicates that some unspecified item is coreferential to the matrix subject (Curnow 2002:12). The language generally used to demonstrate logophoric verbal affixes is Gokana.

Gokana

Gokana is a language of the Benue-Congo family.[citation needed] It uses the verbal suffix -èè, with several different phonological variations to indicate logophoricity (Curnow 2002:10).This can be seen in the example below.

?. aè kɔ aè dɔ he said he fell 'Hei said that hej fell' ?. aè kɔ aè divèè e he said he fell-LOG 'Hei said that hei fell' (Hyman & Comrie 1981:20)

The above example also shows that in Gokana the verbal affix contrasts with its own absence as opposed to contrasting with another affix or pronoun. Because of this, the verbal affix gives no indication of person.[citation needed] As mentioned above,[clarification needed] logophoric verbal affixes can lead to ambiguities. This is demonstrated in the Gokana example below.

?. lébàreè kɔ aè dɔ-ɛ Lebare said he hit-LOG him 'Lebarei said hei hit himj/ Lebarei said hej hit himi' (Hyman & Comrie 1981:24)

Logophoric Pronouns

Ewe

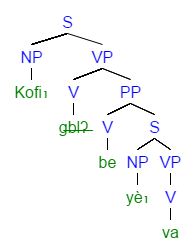

Ewe is a language of the Niger-Congo family,[citation needed] which exhibits formally distinct logophoric pronouns.[citation needed] For example, the third person singular pronoun yè is used only in contexts in which the perspective of an individual other than the speaker is being represented.[citation needed] These special forms are a means of unambiguously identifying the nominal co-referent in a given sentence:[citation needed]

c. Tsali gblʔ na-e be ye-e dyi yè gake yè-kpe dyi. Tsali say to-Pron that Pron beget LOG but LOG be victor ‘Tsaliii told himj (i.e., his father) that hej begot himi but hei was the victor.’ (Clements 1975:152)

Notably, logophoric pronouns such as yè may occur at any level of embedding within the same sentence,[citation needed] and in fact, the antecedent with which it has co-referent relation need not be in the same sentence.[citation needed] The semantic condition imposed on the use of these logophors is that the context in which they appear must be reflective of another individual's perception, and not the speaker's subjective account of the linguistic content being transmitted;[citation needed] however, a purely semantic account is insufficient in determining where logophoric pronouns may appear.[citation needed] More specifically, even when the semantic conditions which license the use of logophors are satisfied, they may not appear in grammatical sentences.[clarification needed][citation needed] Clements demonstrates that these forms may only be introduced by clauses head by the complementizer "be".[citation needed] In Ewe, this word has the function of designating clauses in which the feelings, thoughts, and perspective of an individual other than the speaker is being communicated.[citation needed] Thus, although it is primarily the discursive context which licenses the use of logophoric pronouns in Ewe, syntactic restrictions also play a role in the grammaticality of indirect discourse.[citation needed]

Wan

In Wan, a language spoken primarily in the Ivory Coast, logophoric pronouns ɓā (singular) and mɔ̰̄ (plural) are used to indicate the speech of those who are introduced in the preceding clause (Nikitina 2012).

d yrā̠mū é gé mɔ̰̄ súglù é lɔ̄ children DEF said LOG.PL manoic DEF ate 'The childreni said theyi had eaten the manoic.' e yrā̠mū é gé à̰ súglù é lɔ̄ children DEF said 3PL manoic DEF ate 'The childreni said theyj had eaten the manoic.' (Nikitina 2012:283)

These pronouns can take the same syntactic positions as personal pronouns (e.g. subjects, objects, possessors, etc) (Nikitina 2012). They appear with verbs that have to do with mental and psychological activities and states, and are most often used during speech reports (Nikitina 2012). In casual conversation, using perfect form when speaking of past speech is often associated with logophoricity, as it implies that the event is more relevant to the current speech report (Nikitina 2012).

If in a case the speaker participates in the reported situation, their voice may be ambiguous as they may be confused with the voices of other characters in the discourse.[citation needed] Ambiguity with logophors also arise from reports where someone is reporting character A's report on character B's discourse.[citation needed] This is known as a nested report.[citation needed]

f. è gé kólì má̰, klá̰ gé dóō ɓāā nɛ̰́ kpái gā ɔ̄ŋ́ kpū wiá ɓā lāgá 3SG said lie be hyena said QUOT LOG.SG.ALN child exact went wood piece enter LOG.SG mouth 'Hei said: It's not true. Hyenaj said myi,LOG own child went to enter a piece of wood in hisj,LOG mouth.' (Alternative interpretation: 'Hisj,LOG own child went to enter a piece of wood in myi,LOG mouth.') (Nikitina 2012:293)

Here, in example f, a character reports on another character's (hyena's) speech. Logophoric pronouns are used for both characters, so they are distinguished from the current speaker, but not from each other.

Abe

Abe is a Kwa language[citation needed] spoken in the Ivory Coast[citation needed] that uses two classes of third person pronouns: o-pronouns and n-pronouns (Koopman 1989, p. 2). O-pronouns behave like English pronouns.[citation needed] N-pronouns, in additional to being used as a referential pronoun,[citation needed] are also used as a logophoric pronoun when embedded under a logophoric verb.[citation needed] In Abe, all logophoric verbs are verbs of saying that also take a kO-complement.[citation needed][clarification needed] In non-logophoric contexts (1a), reference with the matrix subject is possible with both o-pronoun and n-pronoun, but in logophoric contexts (1b), note the disjoint reference of o-pronoun:

(1) a. yapii ka api ye Oi,j/n(i),j ye sE

Yapi tell Api ye he is handsome

b. yapii hE kO Oj/ni,(j) ye sE

Yapi said kO he is handsome

(Koopman 1989: 580 (66))

However, logophoric effects are only observed within a subset of kO-complements[citation needed] (in 2a but not 2b). Logophoricity is sensitive to the source of information (see Sells 1987), which is a relevant factor in determining which arguments of a logophoric verb exhibit logophoric effects.[citation needed]

(2) a. m hE apii kO Oi,j/ni ye sE

I said to Api kO she is handsome.

b. yapii ce kO Oi,j/ni,j ye sE

Yapi heard kO he is handsome.

(Koopman 1989: 580 (67))

Long Distance Reflexive Logophors

Chinese

Liu (2012) does not consider Chinese to be a pure logophoric language, but believes that the referential use of some of its reflexives are decidedly logophoric. In Chinese, there are two types of long-range third person reflexives, simplex and complex. They are ziji and Pr-ziji (pronoun morpheme and ziji), respectively. The relationship between these reflexives and the antecedents are logophoric. The distance between the reflexives and their antecedents can be many clauses and sentences apart. Ziji is used logophorically.

a. Zhangsani renwei [Lisij kan-bu-qi zijii/j] Zhangsan think Lisi look-not-up self 'Zhangsani thinks Lisij looks down on himi/himselfi.' b Wo renwei "ni bu yinggai kan-bu-qi wo." I think, "You should not look down on me." (Chou 2012:18)

Example a shows that the Chinese ziji can be used as both a locally bound anaphor and as a long distance logophor.

In Chinese, there exists a Blocking Effect in which the long-distance reading of ziji is not possible because of a difference in POV features between ziji and the embedded CP (Chou 2012). One of these environments that cause blocking is when the third person embedded subject in example a is replaced with the first or second person pronoun, as in example c, which restricts the referencing of ziji to only the local antecedent (Chou 2012).

c Zhangsani renwei [nij kan-bu-qi zijij/*i] Zhangsan think you look-not-up self 'Zhangsani thinks youj should not look down on *himi/yourselfj' (Chou 2012:18)

In c, ziji can only refer to the second person pronoun ni, as ziji takes the POV feature of the embedded subject. The POV of the matrix subject is third person, which clashes with the embedded CP subject's POV, which is the POV of ziji.

While the logophoric use of Pr-ziji is optional, its primary role is to be an emphatic or intensive expression of pronoun. Emphatic use is shown in example l. In example sentence l that uses a Pr-ziji for emphatic purposes, substituting the Pr-ziji (here, taziji) for ziji can reduce the emphasis and suggest logophoric referencing (Liu 2012).

l. Lao Tong Baoi suiran bu hen jide zufu shi zenyang "zuoren", dan fuqin de qinjian zonghou,tai shi qinyan

Old Tong Bao although not very recall grandpa be what sort of man but father MM diligence honesty he just with his own eyes

kanjian de; tazijii ye shi guiju ren...

see PA himself also be respectable man

'Although Old Tong Baoi couldn't recall what sort of man his grandfather was, hei knew his father had been hardworking and

honest—he had seen that with his own eyes. Old Tong Bao himselfi was a respectable person;...' (Liu 2012:75)

Japanese

Prior to the first usage of the term "logophor", Kuno Susumu (1972) analyzed the licensing of the use of the Japanese reflexive pronoun zibun. His analysis focused on the occurrence of this pronoun in direct discourse in which the internal feeling of someone other than the speaker is being represented. Kuno argues that what permits the usage of zibun is a context in which the individual which the speaker is referring to is aware of the state or event under discussion - i.e., this individual's perspective must be represented.

g. Johni wa, Mary ga zibuni ni ai ni kuru hi wa, sowasowa site-iru yo.

meet to come days excited is

'John is excited on days when Mary comes to see him.'

h. *Johni wa, Mary ga zibuni o miru toki wa, itu mo kaoiro ga warui

self see when always complexion bad

soo da.

I hear

'I hear that John looks pale whenever Mary sees him.' (Kuno 1972:182)

The g. sentence is considered grammatical because the individual being discussed (John) is aware that Mary comes to see him. Conversely, sentence h. is ungrammatical because it is not possible for John to look pale when he is aware that Mary sees him. As such, John's awareness of the event or state being communicated in the embedded sentence determines whether or not the entire sentences is grammatical. Similarly to other logophors, the antecedent of the reflexive zibun need not occur in the same sentence, as is the case for non-logophoric reflexives. This is demonstrated in the example above, in which the antecedent in sentence a. occurs in the matrix sentence, while zibun occurs in the embedded clause. Although traditionally referred to as "indirect reflexives", logophoric pronouns such as zibun are also referred to as long-distance, or free anaphors (Reuland 2006:4).

Although the grammatical usage of zibun is conditioned by semantic factors (namely, the representation of the direct internal feeling or knowledge of an individual other than the speaker), syntactic restrictions also play a role. For example, the usage of zibun in a matrix sentence requires coreference with the subject of the sentence (not the object):

i. John wa Mary o zibun no i.e. de korosita.

self 's house in killed

'John killed Mary in (lit.) self's house.'

j. Mary wa John ni zibun no ie de koros-are-ta.

'Mary was killed by John in (lit.) self's house.' (Kuno 1972:178)

In the above sentences, zibun can only refer to the subjects of the sentences - "John" in sentence i. and "Mary" in sentence j. As such, the passivized sentence j. is not equivalent in meaning to sentence e. Importantly, that coreferent of zibun need not be aware of the action or state represented in the sentence - for instance, it is not implied in sentence j. that Mary was aware that she was killed in her house. This use of zibun appears to be restricted to a non-logophoric context. In line with Clements' characterization of indirect reflexives, the logophoric pronoun is homophonous with the (non-logophoric) reflexive pronoun (Clements 1975, p. 3).

Icelandic

In Icelandic, reflexives pronouns are used as obligatory clause-bound anaphor and as logophoric pronouns. The latter correlates to the occurrence of non-clause-bounded reflexives (NCBR) due to its ability to bind with antecedents across multiple subjunctive clause boundaries (Sells 1987, p. 453).:

(1) Formaðurinni varð óskaplega reiður. Tillagan væri avívirðileg. Væri henni beint gegn séri persónulega.

The-chairmani became furiously angry. The-proposal was(subj.) outrageous. Was(subj) it aimed at selfi personally.

'It was aimed at him personally, he expressed.'

(Sells 1987: 453 (26))

The distribution of NCBR correlates with the grammatical mood. Specifically, the binding of the reflexive anaphor and the antecedent across multiple clause boundaries is only possible when the intervening clauses are in subjunctive mood (2b) (Maling 1984, p. 212); binding is prohibited across indicative mood as shown in (2a). Embedding an indicative clause under the verb segja "to say" would allow the subjunctive mood to "trickle down" its daughter nodes, and allow NCBR to bind with the matrix subject (3).:

(2) a. *Joni veit að María elskar sigi

John knows that Maria loves(ind.) REFL

'Johni knows that Maria loves himi.'

b. Joni segir að María elski sigi

John says that Maria loves(subj.) REFL

'Johni says that Maria loves himi.'

(Maling 1984: 212 (2))

(3) Jóni segir að Haraldurj viti að Sigga elski sigi,j.

Jon says(subj.) that Haraldur knows(subj.) that Sigga loves(subj.) REFL

Joni says that Haraldurj knows that Sigga loves himi,j.

(Maling 1984: 223(23b))

Subjunctive mood is typically used for indirect discourse, which correspond to the semantic property of logophoric pronouns. The "trickling down" effect of embedding clauses under the verb segja "to say" allows the reflexive to bind with the subject of the verb of saying, exhibiting the behaviour of logophoric pronouns.

Logophoricity and Binding Theory

Syntactic Accounts

There has been much discussion in linguistic literature on the type of approach that would best account for logophoricity. Syntactic accounts have been attempted within the context of Government and binding theory(Stirling 1993:268). More specifically, Binding Theory organizes nominal expressions into three groups: (i) anaphors, (ii) pronominals, and (iii) R-expressions.[citation needed] The distribution and grammaticality of these are governed by Conditions A, B, and C:[citation needed]

Condition A: An anaphor must be bound within its domain; that is, it must be c-commanded by its co-referent antecedent. An

element's domain is the nearest maximal projection (XP) with a specifier. Condition B: A pronoun must be free within its domain. Condition C: R-expressions must be free.

N.B. An image will be inserted here for clarification

Anaphors are not referential in and of themselves; they must be co-indexed to an antecedent.[citation needed]. Seth A. Minkoff (2004) argues that logophors are a particular subset of anaphora that refer to the “source of a discourse” - i.e., the original (secondary) speaker, not the messenger relaying the information.[citation needed] For this reason, he argues that they form a special class of anaphors that may be linked to a referent outside their projected domain. Alternatively, Lesley Stirling (1993) contends that logophors are not anaphors, as they violate Condition A of Binding Theory. More specifically, there is no c-command relation between the antecedent and the logophor to which it co-refers. In relation to this, logophors and long-distance reflexives are not in complementary distribution with non-logophoric personal pronouns, as anaphors are. Additionally, logophors do not satisfy Condition B, as they are not referentially free within their domain - thus, they are not true pronominals, based on this condition.

Stirling (1993) points out that although certain syntactic constraints influence the distribution of logophoric forms (such as requiring that an antecedent be a grammatical subject (Kuno 1972), syntactic binding is not crucial, nor sufficient, to explain the distribution of logophors. For example, a logophoric antecedcent is often restricted to have the semantic role of "source" in a discourse, or the semantic role of "experiencer" of a state of mind. Additionally, whether or not a logophoric form may be used may also be contingent on the lexical semantics of the verb in the matrix clause. There have been attempts to move beyond a solely syntactic approach in recent literature.

Minkoff's (2004) Principle E

Since logophors cannot be entirely accounted for given the conditions of canonical Binding Theory (Stirling 2005:268), modifications to this theory have been posited. For example, Seth A. Minkoff (2004) suggests that logophoricity requires a new principle to be added to the set of conditions held by Binding Theory. He proposes Principle E which is stated thus:

Principle E: A free self-anaphor must co-refer with and be in the backward co-reference domain of, an expression whose

co-referent typically possesses consciousness (Minkoff 2004:488)

The backward co-reference domain is a specification of the general concept of domain found in binding theory. For anaphors, domain is defined as the smallest XP node in a tree with a subject that contains the DP (Sportiche, Koopman & Stabler 2014:169). Backward co-reference domain means that node X is in the backward co-reference domain of node Y if there are two further nodes, A and B, such that A predicates B, A dominates X, and B dominates Y (Minkoff 2004:488). Minkoff (2004) addresses the two crucial differences his Principle E holds with binding theory. First it operates distinctly in the backward co-reference domain, rather than the more general operation of c-command. It is also sensitive to the attribute on consciousness, unlike the syntax specific binding theory.

Free anaphors and opacity

Free or long-distance anaphors are able to take an antecedent beyond their domain subject;[citation needed] this is a common situation in which to find logophors.[citation needed] Three scenarios may allow these exceptions: (i) if the logophor is properly bound (e.g. c-commanded and co-indexed) by an antecedent outside its local domain; (ii) if accurately interpreted by an antecedent that does not c-command; or (iii) if accurately interpreted without an explicitly stated antecedent.[citation needed] These lead to an extended version of Condition A that applies more generally to locality:

The dependent element (logophor) L is linked to an antecedent A if and only if A is contained within B, as in

... [B ... w ... L ...] ...

in which B is the minimal category containing A, L, and opacity factor w (Koster 1984).

Under this interpretation, domain is no longer limited to the maximal projection of the logophor.[citation needed] The opacity factor (w) is best described as a variable that takes a different value for different types of dependent elements (L); its role is to delineate domains with respect to category heads (V, N, A, or P). Koster gives the following example as illustration:

... V [PP P NP]

explaining that P is the opacity factor, as head of the maximal projection PP, and "blocks" V from governing NP. Instead, the locality domain that governs NP is the maximal projection of its phrasal head—PP.

Logophors vs Indirect Reflexives

Hagège (1974) found that logophors are distinct from “indirect reflexive” pronouns, and that many languages in fact have different sets of pronouns for each use. He and Clements (1975) agree, however, that the functions of the two types are similar. Clements' proposed conditions in which a logophoric role applies are detailed in the introduction.

- (example from Ewe – Reuland)

Logical Variables

To account for the distribution of n-pronouns vs o-pronouns in Abe, Koopman presented a syntactic analysis of n-pronouns as logical variables, and are Ā-bound by an operator at the Comp. n-pronouns are [+n] and [-n] includes lexical NP, QPs, and O-pronouns, and [+n] elements cannot bind [-n] and vice versa. In logophoric contexts, the complementizer kO is in fact a verb with a [+n] silent subject. The theta role assignment to the subject accounts for the semantic property of logophoric pronouns.[citation needed] She[who?] proposes that if this can be generalized to other languages, then there is no "logophoric pronouns", but two distinct mechanisms coming together to give the effect of logophoricity.

Semantic Accounts

Discourse Representation Theory

Sells' (1987) Account

Peter Sells introduced a semantic account of logophoricity using Discourse Representation Structure. This approach allows for the possibility of binding between an antecedent and a logophor within the same sentence or across sentences within a discourse. He introduced three semantic roles, or primitives, which occur in discourse: source, self, and pivot. The source refers to the individual who is the intentional communicator, the self to the individual whose perspective is being reported, and the pivot to the individual who is the deictic center of the discourse, i.e., the one from whose physical perspective the content of the report is being evaluated.(Sells 1987:455-456). The predicates which correspond to these primitives are represented by Discourse Markers (DMs). Additionally, there is a Discourse Marker (S) which stands for the speaker of the discourse. Sells imposes a condition that the DMs associated with a primitive predicate are able to be anaphorically related to other referents in the discourse.

This account attempts to explain logophoricity as the result of the interaction between the three primitives. For instance, if there is a logophoric pronoun in the discourse, it is interpreted with regards to a noun phrase (NP) that has a particular role assigned to it. As such, a logophoric NP is associate with a NP that is also associated with a particular semantic role. It may be the case that all three roles are assigned to one NP, such as the subject of the main verb in the following example:

(4) Tarooi wa Yosiko ga zibuni o aisiteiru to itta.

'Tarooi said that Yosiko loved selfi.'

(Sells 1987:461)

Since Taroo is the individual who is intentionally communicating the fact that Yosiko loved him, he is the source. Taroo is also the self, as it his perspective being reported, and he is additionally the pivot, as it his from his location that the content of the report is being evaluated.

(5) N.B. A visual aid will be inserted here.

In (5), which is the Discourse Representation Structure for the Sentence in (4), S stands for the external speaker, u stands for a predicate (in this example, Taroo), and p stands for a proposition. The inner box contains the content of the proposition, which is that Yosiko (a predicate of the embedded clause, marked with v) loved Taroo, another predicate, which is marked by z. As can be inferred by the diagram, z is assigned the role of pivot, which corresponds to the NP Taroo.

Stirling's (1993) Account

See also

- Bound variable pronoun

- Coreference

- Logical Form

- Obviative

- Reflexive pronoun

- Subjunctive mood

- Switch reference

References

- Hagège, Claude (1974), "Les pronoms logophoriques", Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris, 69: 287–310

- Chou, Chao-Ting T. (2012), "Syntax-Pragmatics Interface: Mandarin Chinese Wh-the-hell and Point-of-View Operator", Syntax, 15: 1–24

- Clements, George N. (1975), "The Logophoric Pronoun in Ewe: Its Role in Discourse", Journal of West African Languages, 2: 141–177

- Curnow, Timothy J. (2002), "Three Types of Logophoricity in African Languages", Studies in African Linguistics, 31: 1–26

- Hedinger, Robert (1984), "Reported Speech in Akɔɔse", Studies in African Linguistics, 12 (3): 81–102

- Hyman, Larry M. & Bernard Comrie (1981), "Logophoric Reference in Gokana", Studies in African Linguistics, 3 (1): 19–37

- Koopman, Hilda (1989), "Pronouns, Logical Variables, and Logophoricity in Abe", Linguistic Inquiry, 20 (4): 555–588

- Kuno, Susumu (1972), "Pronominalization, Reflexivization, and Direct Discourse", Linguistic Inquiry, 3: 161–195

- Liu, Lijin (2012), "Logophoricity, Highlighting and Contrasting: A Pragmatic Study of Third-person Reflexives in Chinese Discourse", English Language and Literature Studies, 2: 69–84

- Maling, Joan (1984), "Non-Clause-Bounded Reflexives in Modern Icelandic", Linguistics and Philosophy, 7 (3): 211–241

- Minkoff, Seth A., "Consciousness, Backward Coreference, and Logophoricity", Linguistic Inquiry, 35 (3): 485–494

- Nikitina, Tatiana (2012), "Logophoric Discourse and First Person Reporting in Wan (West Africa)", Anthropological Linguistics, 54: 280–301

- Reuland, E. (2006), "Chapter 38. Logophoricity", The Blackwell Companion to Syntax, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 1–20, ISBN 9781405114851, retrieved 2014-10-28

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Sells, Peter (1987), "Aspects of Logophoricity", Linguistic Inquiry, 18 (3): 445–479

- Stirling, Lesley (1993), "Chapter 6 Logophoricity", Switch-Reference and Discourse Representation, Cambridge University Press, pp. 252–307, ISBN 9780521023436, retrieved 2014-11-11