Detroit Industry Murals

The Detroit Industry Murals are a series of frescoes by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, consisting of twenty-seven panels depicting industry at the Ford Motor Company. Together they surround the Rivera Court in the Detroit Institute of Arts. Painted between 1932 and 1933, they were considered by Rivera to be his most successful work.[1] On April 23, 2014, the Detroit Industry Murals were given National Historic Landmark Status. [2]

The two main panels on the North and South walls depict laborers working at Ford Motor Company's River Rouge Plant. Other panels depict advances made in various scientific fields, such as medicine and new technology. The series of murals, taken as a whole, represents the idea that all actions and ideas are one.

Commission

In 1932 Wilhelm Valentiner commissioned Diego Rivera for an ambitious project. The plan for the project was to have Diego Rivera paint 27 fresco murals in the Detroit Institute of Art.[3] They also wanted Rivera to incorporate the industry of Detroit as a whole, and not just the automobile industry. Rivera was perfect for the job. Before accepting Valentiers proposal Rivera had just completed a mural at the California School of Fine Arts, now called the San Francisco Art Institute. The mural that he created there clearly displayed his painterly ability as well as his interest towards the modern industrial culture in the United States. In the agreement for the commission, the DIA was expected to pay all expenses towards materials while Rivera was expected to pay for his own assistance.[4] At the time materials were incredibly expensive and the agreement that the DIA and Rivera settled on was considered a great deal. Edsel Ford contributed $20,000 to make the deal possible.

North and South walls

From the 27 murals that Rivera painted at the Detroit Institute of Art, the two largest murals are located on the north and south walls. The murals depict the workers at the Ford River Rouge Complex in Dearborn Michigan. During the time Detroit was an advanced industrial complex, and was home to the largest manufacturing industry of the world.[5] In 1927, the Ford Motor Company was introducing advanced technological improvements for their assembly line, one of which was the revolutionary automated car assembly line. Another revolutionary quality of the industry in Detroit was their ability to manufacture every single component for their motor car. Detroit had factories within factories that produced everything from steel, electric power, and even cement. Although, Detroit was popular for their masterful mass production of the motor can, they also manufactured ships, tractors, and airplanes, and if that is not impressive enough, Detroit also owned all of the railroads for shipping. This impressive integrated industrial manufacturing center is what Diego Rivera diligently pursued to capture in his masterful work at the Detroit Institute of Art that would later be known as the “Detroit Industry Murals”.

When Rivera started the project he immediately began researching the facilities at the Ford River Rouge Complex. He spent three months touring all of the plants, and prepared hundreds of sketches and concepts for the mural.[6] He also had his own photographer that was assigned to him as aid for Rivera’s research in finding visual reference material. The photographers name was W.J. Stettler, and was also the official photographer for the River Rouge plant.[7] Rivera was truly amazed by the perfect examples of technology and modernity that was present in Detroit’s plants. Although, Rivera was obviously intrigued with the industry that revolved around the motor car, he also expressed an interest in the pharmaceutical industry. He even spent some time at the Parke-Davis Pharmaceutical plant in Detroit to conduct even more research for his commission at the DIA.

Diego Rivera managed to complete the monumental commission in a very short amount of time. He only spent eight months to complete the work. In order for him to have completed the work in such a short amount of time, Rivera along with his assistants had a exhausting work schedule, and would work fifteen hour days often. It is also known that they would often have no brakes between work, causing Rivera to loose 100lbs of weight. Rivera also had a bad reputation with his assistants in that he would not pay them very well, and at one point his assistants actually protested for better wages.

At the time Rivera’s assistants were not the only workers protesting. Rivera started working on the mural in 1932 which overlapped the Great Depression. In Detroit one out of four laborers were unemployed, and at the time the Ford Motor Company was experiencing political/social unrest with their workers. There was even an event were 6,000 workers were on strike, but was sabotaged and ended in five deaths and wounding many others. Considering Rivera’s reputation as a revolutionary artist, it is apparent that Rivera was most likely inspired by the charged atmosphere of protest against one of the worlds most powerful industrial cities.

The DIA inner courtyard is ruled by two gigantic murals located on the north and south walls. These two murals are the climax to the narrative that Rivera depicted in his 27 panel mural. The north wall puts the worker at center and depicts the manufacturing process of Fords famous 1932 V8 engine.[8] The mural also visually composes the relationship between man and the machine as the main theme of the mural. In an age of mechanical reproduction, the boundary between man and the machine was often questioned. While machine was imitating the abilities of man, and man being forced to operate in a machine like manner often sparked concerns regarding ethical rights for the working class majority. Other qualities that Rivera incorporated into the north wall that commented on mechanical reproduction were: blasting furnaces that are making iron ore, foundries that are making molds for parts, conveyor belts carrying the cast parts, machining operations and finally inspections. Rivera depicted the entire manufacturing process on the large north side mural. He also depicts the chemical industry on the right and left side of the northern wall. The imagery consists of a juxtaposition of scientists that are producing poison gas for warfare and scientists that are producing vaccines for medical purposes.

On the opposite side of the north wall Rivera depicts the manufacturing process of the exterior parts to the motor car. In this mural Rivera focuses on technology as an important quality of the future. He then allegorizes this concept through one of the huge parts pressing machines that is depicted in the mural. The machine is meant to symbolize the story of the Aztec goddess Coatlicue.[9] In Aztec mythology Coatlicue was the mother of the gods, and gave birth to the moon, stars, and Huitzilopochtli, the god of the sun and war. The story of Coatlicue was important to the Aztecs and summarized the complexity of their culture and religious beliefs. In comparison to the aztec story, technology had become what the modern world found to be important culturally, and at times supported and defended technology as passionately as a religion. [10]

Notoriety

Even before the murals were made there had been controversy surrounding Rivera's Marxist philosophy. Critics viewed them as Marxist propaganda. When the murals were completed, the Detroit Institute for the Arts invited various clergymen to comment. Catholic and Episcopalian clergy condemned the murals for supposed blasphemy. The Detroit News protested that they were "vulgar" and "un-american." As a result of the controversy, 10,000 people visited the museum on a single Sunday, and the budget for it was eventually raised.

One panel on the North wall displays a Christ-like child figure with golden hair reminiscent of a halo. Flanking it on the right is a horse (rather than the donkey of Christian tradition); on the left is an ox. Directly below are several sheep, an animal often part of the traditional Nativity which in some cases is intended as a symbol of Christ as Agnus Dei. A doctor fills the role of Joseph and a nurse that of Mary; together they are administering the child a vaccination. In the background three scientists, like biblical Magi, are engaged in what appears to be a research experiment. This part of the fresco is clearly a modern take on traditional images of the holy family, but some critics interpret it as parody rather than homage.[11]

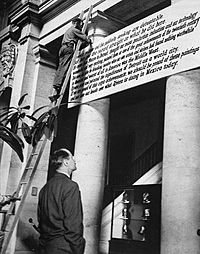

At its unveiling the panel so offended some members of Detroit's religious community that they demanded it be destroyed, but commissioner Edsel Ford and DIA Director Wilhelm Valentiner held firm, and it remains in place today.[11] During the reactionary McCarthy era of the 1950s, the DIA erected a sign above the entrance to the Rivera Court that read:

"Rivera's politics and his publicity seeking are detestable. But let's get the record straight on what he did here. He came from Mexico to Detroit, thought our mass production industries and our technology wonderful and very exciting, painted them as one of the great achievements of the twentieth century. This came after the debunking twenties when our artists and writers found nothing worthwhile in America and worst of all in America was the Middle West.

Rivera saw and painted the significance of Detroit as a world city. If we are proud of this city's achievements, we should be proud of these paintings and not lose our heads over what Rivera is doing in Mexico today.

Rivera depicts the workers as in harmony with their machines and highly productive. This view reflects both Karl Marx's begrudging admiration for the high productivity of capitalism and the wish of Edsel Ford, who funded the project, that the Ford motor plant be depicted favorably. Rivera depicted byproducts from the ovens being made into fertilizer and Henry Ford leading a trade-school engineering class.

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Michigan

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Wayne County, Michigan

References

- ^ The Detroit Institute of Arts.[1] "Detroit Industry". Accessed on 18 May 2013. "The Detroit Industry fresco cycle in Rivera Court is the finest example of Mexican muralist work in the United States; Rivera considered it the most successful work of his career."

- ^ Detroit Free Press. [2] "Iconic Diego Rivera murals at DIA named National Historic Landmark". Accessed on 25 April 2014.

- ^ Rochfort, Desmond (1993). Mexican Muralists. Chronicle Books. p. 126.

- ^ Resmond, Desmond (1993). Mexican Muralists. Chronicle Books. p. 126.

- ^ Rochfort, Desmond (1993). Mexican Muralists. Chronicle Books. p. 126.

- ^ Rochfort, Desmond (1993). Mexican Muralists. Chronicle Books. p. 126.

- ^ Rochfort, Desmond (1993). Mexican Muralists. Chronicle Books. p. 126.

{{cite book}}: Missing|author1=(help) - ^ Rochfort, Desmond (1993). Mexican Muralist. Chronicle Books. p. 127.

- ^ Labastida, Jaime (1993). Encuentros Con Diego Rivera. El Colegio Nacional. p. 260.

- ^ Labastida, Jaime (1993). Encuentros Con Diego Rivera. El Colegio Nacional. p. 261.

- ^ a b University of Michigan An Analysis of Diego Rivera's Exhibitions in the United States.

- ^ Making the Modern: Industry, Art, and Design in America (1994), by Terry Smith.

External links

- A high resolution panoramic view of the murals can be seen at Rivera Court by Synthescape.

- Detroit Industry: The Murals of Diego Rivera, Don Gonyea, NPR, April 22, 2009, includes audio, text, slideshow, and video of Rivera painting the murals.

- "Symbolism in Diego Rivera's Detroit Industry Murals"

- Meet America's Newest Historic Landmarks, PBS Newshour, April 27, 2014.