Monrovia

Monrovia | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Monrovia | |

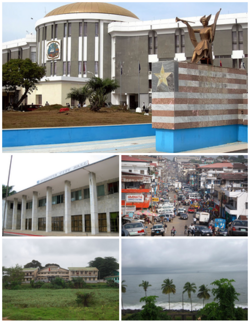

Images top, left to right: Capitol Building, Monrovia City Hall, Downtown Monrovia, University of Liberia, Monrovia Bay | |

| Country | |

| County | Montserrado |

| District | Greater Monrovia |

| Established | April 25, 1822 |

| Named for | James Monroe - U.S. President |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mary Broh |

| Area | |

• City | 5 sq mi (13 km2) |

| Population (2008)[1] | |

| • Metro | 970,824 |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

Monrovia /mənˈroʊviə/[2][3] is the capital city of the West African country of Liberia. Located on the Atlantic Coast at Cape Mesurado, Monrovia had a population of 970,824 as of the 2008 census. With 29% of the total population of Liberia, Monrovia is the country's most populous city.[4]

Monrovia is Liberia's cultural, political and financial hub. The body that administers the government of Greater Monrovia District is the Monrovia City Corporation.

Founded in 1822, Monrovia was the first permanent Black American settlement in West Africa. Monrovia's economy is dominated by its harbour and as the location of Liberia's government offices.

Etymology

Monrovia is named in honor of U.S. President James Monroe, a prominent supporter of the colonization of Liberia. Along with Washington, D.C., it is one of two national capitals to be named after a U.S. President.

History

In 1816, with the aim of establishing a self-sufficient colony for emancipated American survivors of slavery, something that had already been accomplished in Freetown, the first settlers arrived in Africa from the United States, under the auspices of the American Colonization Society.[5] They landed at Sherbro Island in present-day Sierra Leone. The undertaking was a shambles and many settlers died.

In 1822, a second ship rescued the settlers and took them to Cape Mesurado, establishing the settlement of Christopolis. In 1824, the city was renamed to Monrovia after James Monroe, then President of the United States, who was a prominent supporter of the colony in sending freed Black slaves to Liberia and who saw it as preferable to emancipation in America. [citation needed]

In 1845, Monrovia was the site of the constitutional convention held by the American Colonization Society which drafted the constitution that would two years later be the constitution of an independent and sovereign Republic of Liberia.[6]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Monrovia was divided into two parts: (1) Monrovia proper, where the city's Americo-Liberian population resided and was reminiscent of the Southern United States in architecture; and (2) Krutown, which was mainly inhabited by ethnic Krus but also Bassas, Grebos and other ethnicities.[7] Of the 4,000 residents, 2,500 were Americo-Liberian. By 1926, ethnic groups from Liberia's interior began migrating to Monrovia in search of jobs.[7]

In 1979, the Organisation of African Unity held their conference in the Monrovia area, with then president William R. Tolbert as chairman. During his term, Tolbert improved public housing in Monrovia and decreased by 50% the tuition fees at the University of Liberia. A military coup led by Samuel Doe ousted the Tolbert government in 1980, with many members being executed.

The city was severely damaged in the First and Second Liberian Civil Wars, notably during the siege of Monrovia, with many buildings damaged and nearly all the infrastructure destroyed. Major battles occurred between Samuel Doe's government and Prince Johnson's forces in 1990 and with the NPFL's assault on the city in 1992. A legacy of the war is a large population of homeless children and youths, either having been involved in the fighting or denied an education by it.

In 2002, Leymah Gbowee organized the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace with local women praying and singing in a fish market in Monrovia.[8] This movement helped bring an end to the Second Liberian Civil War in 2003 and the election of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in Liberia, the first African nation with a female president.[9]

As of September 2014, an ongoing Ebola epidemic has been affecting the city.[10]

Geography

Monrovia lies along the Cape Mesurado peninsula, between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mesurado River, whose mouth forms a large natural harbor. The Saint Paul River lies directly north of the city and forms the northern boundary of Bushrod Island, which is reached by crossing the "New Bridge" from downtown Monrovia. Monrovia is located at 6°19′N 10°48′W / 6.317°N 10.800°W. Monrovia is Liberia's largest city and its administrative, commercial and financial center.

The city is located in Montserrado County. The small town of Bensonville is actually the capital of Montserrado County.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Monrovia features a tropical monsoon climate (Am).[11] During the course of the year Monrovia sees a copious amount of precipitation. Monrovia averages 5,100 mm (200 in) of rain per year. In fact, Monrovia is the wettest capital city, receiving more annual precipitation on average, than any other capital in the world.[3] The climate features a wet season and a dry season, but precipitation is seen even during the dry season. Temperatures remain constant throughout the year averaging around 26 °C (79 °F).

| Climate data for Monrovia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32 (90) |

33 (91) |

32 (90) |

33 (91) |

34 (93) |

31 (88) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.9 (87.6) |

31 (88) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.8 (89.2) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30 (86) |

28.9 (84.0) |

29 (84) |

29 (84) |

30 (86) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.9 (78.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25.5 (77.9) |

26 (79) |

26 (79) |

25.7 (78.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 21 (70) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22 (72) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21 (70) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

21.1 (70.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 13 (55) |

20 (68) |

19 (66) |

16 (61) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

16 (61) |

18 (64) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

16 (61) |

14 (57) |

13 (55) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31 (1.2) |

56 (2.2) |

97 (3.8) |

216 (8.5) |

516 (20.3) |

973 (38.3) |

996 (39.2) |

373 (14.7) |

744 (29.3) |

772 (30.4) |

236 (9.3) |

130 (5.1) |

5,140 (202.3) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1mm) | 5 | 5 | 10 | 17 | 21 | 26 | 24 | 20 | 26 | 22 | 19 | 12 | 207 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86.5 | 85 | 84.5 | 85.5 | 84 | 85.5 | 85.5 | 85.5 | 89 | 88 | 87.5 | 86 | 86.0 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org for average temperatures (altitude: 5m)[11] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: BBC Weather for record temperatures, precipitation, rainy days and sunshine[12] | |||||||||||||

Neighbourhoods

The city of Monrovia consists of several districts, spread across the Mesurado peninsula, with the greater Metropolitan area encircling the marshy Mesurado river's mouth. The historic downtown, centered around Broad Street, is at the very end of the peninsula, with the major market district, Waterside, immediately to the north, facing the city's large natural harbor.

Northwest of Waterside is the large, low-income West Point community. To the west/southwest of downtown lies Mamba Point, traditionally the city's principal diplomatic quarter, and home to the Embassies of the United States and United Kingdom as well as the European Union Delegation. South of the city center is Capitol Hill, where the major institutions of national government, including the Temple of Justice and the Executive Mansion, are located.

Further east down the peninsula is the Sinkor section of Monrovia. Originally a suburban residential district, today Sinkor acts as Monrovia's bustling mid-town, hosting many diplomatic missions, as well as major hotels, businesses, as well as several residential neighborhoods, including informal communities such as Plumkor, Jorkpentown, Lakpazee and Fiamah.

Sinkor is also home to the city's secondary airport, Spriggs Payne, and the area immediately nearby, called Airfield, is a major nightlife district for the whole city. Further east of the Airfield is the Old Road section of Sinkor, which is predominantly residential, including informal settlements like Chugbor and Gaye Town.

At the southeasterly base of the peninsula is the independent township of Congo Town, and to its east is the large suburb of Paynesville. Other suburbs such as Chocolate City, Gardnersville, Barnersville, Kaba Town, Dandawailo, and New Georgia lie to the north, across the river. To the east are the neighborhoods of New Kru Town and Logan Town. To the far east are the suburbs of Stockton Creek Bridge, Caldwell, Louisiana and Cassava Hill.

- Other neighborhoods and suburbs of Monrovia include

Economy

Monrovia's economy is dominated by its harbour - the Freeport of Monrovia - and as the location of Liberia's government offices. Monrovia's harbor was significantly expanded by U.S. forces during the Second World War and the main exports include latex and iron ore.

Materials are also manufactured on-site, such as cement, refined petroleum, food products, bricks and tiles, furniture and chemicals. Located on Bushrod Island between the mouths of the Mesurado and Saint Paul rivers, the harbor also has facilities for storing and repairing vessels.

Infrastructure

Boats link the city's Freeport of Monrovia, the country's busiest port, with Greenville and Harper.[13] The nearest airport is Spriggs Payne Airport, located less than four miles (6.4 km) from the city center. Roberts International Airport, the largest international airport in Liberia, is 60 km (37 miles) away in Harbel.[13]

Monrovia is connected with the rest of the country via a network of roads and railways. Monrovia is listed as the home port by between ten and fifteen percent of the world's merchant shipping, registered in Liberia under Flag of Convenience arrangements. Both private taxis and minibuses run in the city, and are supplemented by larger buses run by the Monrovia Transit Authority. Prior to the wars, the Mount Coffee Hydropower Project provided electricity and drinking water to the city.[14]

In recent years (2005–present) the roads on many streets in Monrovia have been rebuilt by the World Bank and the Liberian Government. Private and public infrastructures are being built or renovated as reconstruction takes place.

Government

Monrovia lies geographically within Montserrado County, but is administered separately. Monrovia's Monrovia City Corporation runs many services inside the city. Monrovia is governed as a metropolitan city called Greater Monrovia District.

Former mayors include:

- W. F. Nelson, 1870s[15]

- C. T. O. King, 1880s and served three terms[16]

- H. A. Williams, 1890s[17]

- Gabriel M. Johnson, 1920s[18]

- Nathan C. Ross, 1956-1969[19]

- Ellen A. Sandimanie, 1970s and first woman to hold the position[20]

- Ophelia Hoff Saytumah, 2001–2009

- Stacy Randall, 2010-2011

Culture and media

Attractions in Monrovia include the Liberian National Museum, the Masonic Temple, the Waterside Market, and several beaches. The city also houses Antoinette Tubman Stadium and the Samuel K. Doe Sports Complex sports stadiums. The arena at Samuel K. Doe is one of the largest stadiums in Africa, with seats for 40,000.[citation needed]

The newspaper industry in Monrovia extends back to the 1820s, when the Liberia Herald opened as one of the first newspapers published in Africa. Today, numerous tabloid style newspapers are printed on daily or bi-weekly basis, most of which are no more than 20 pages. The Daily Talk is a compilation of news items and Bible quotations written up daily on a roadside blackboard in the Sinkor section of Monrovia.[citation needed]

Radio and TV stations are available, with radio being a more prominent source of news as problems with the electric grid make watching television more difficult. UNMIL Radio has been broadcasting since October 1, 2003. It is the first radio station in Liberia to broadcast 24 hours a day, and reaches an estimated 2⁄3 of the population.[21] The state-owned Liberia Broadcasting System broadcasts nationwide from its headquarters in Monrovia.[22] STAR radio broadcasts at 104 FM.[23]

Education

Monrovia is home to the University of Liberia, along with African Methodist Episcopal University, United Methodist University, Stella Maris Polytechnic, and many other public and private schools. Medical education is offered at the A.M. Dogliotti College of Medicine, and there is a nursing and paramedical school at the Tubman National Institute of Medical Arts.

Kindergarten through twelfth grade education is provided by the Monrovia Consolidated School System, which serves the Greater Monrovia area. Schools include Monrovia Central High School, Bostwain High School, D. Twe High School, G. W. Gibson High School and William V. S. Tubman High School.

Pollution

Pollution is a significant issue in Monrovia.[24] Piles of household and industrial rubbish in Monrovia build up and are not always collected by sanitation companies paid by the World Bank to collect this waste.[25]

In 2013, the problem of uncollected rubbish became so acute in the Paynesville area of Monrovia that traders and residents burnt "the huge garbage piles that seemed on the verge of cutting off the main road" out of Monrovia to Kakata.[26]

Flooding brings environmental problems to residents of Monrovia, as flood water mixes with and carries waste found in swamps that are often on the verge of residential areas.[27]

In 2009, one-third of Monrovia's 1.5 million people had access to clean toilets.[28] Those without their own toilets defecate in the narrow alley-ways between their houses, on the beach, or into plastic bags, which they dump on nearby piles of rubbish or into the sea.[28]

Congested housing, no requirement that landlords provide working toilets, and virtually no urban planning "have combined to create lethal sanitation conditions in the capital".[29]

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Monrovia is twinned with:

See also

General:

References

- ^ 2008 National Population and Housing Census. Retrieved November 09, 2008.

- ^ "Definition of Monrovia". The Free Dictionary. Retrieved 2014-01-05. /mənˈroʊviə, mɒnˈroʊviə/

- ^ "Define Monrovia". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2014-01-05. /mənˈroʊviə/

- ^ "Global Statistics". GeoHive. 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ "Map of Liberia, West Africa". World Digital Library. 1830. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- ^ Robin Dunn-Marcos, Konia T. Kollehlon, Bernard Ngovo, and Emily Russ (2005) in Donald A. Ranard (ed.) Liberians: An introduction to their history and culture (Washington: Center for Applied Linguistics) available online here [1]

- ^ a b Tiyambe Zeleza, Dickson Eyoh et al., Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century African History. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ 2009 Peace warrior for Liberia

- ^ CNN, October 31, 2009

- ^ "The terrifying mathematics of Ebola". Channel 4. 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2014-09-11.

- ^ a b "Climate: Monrovia - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ^ "BBC Weather - Monrovia". BBC Weather. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- ^ a b Timberg, Craig (March 12, 2008). "Liberia's Streets, Spirits Brighten; Four Years After War's End, Battered W. African Nation Begins a Slow Reawakening". The Washington Post. pp. A8.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Montserrado County Development Agenda" (PDF). Republic of Liberia. 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- ^ "Trustees of Donations for Education in Liberia Records: 1842-1939". Massachusetts Historical Society. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ Burrowes, Carl Patrick (2004). Power and Press Freedom in Liberia, 1830-1970. Africa World. p. 117. ISBN 1-59221-294-8.

- ^ Payne, Daniel Alexander (1922). A history of the African Methodist Episcopal church: being a volume supplemental to A history of the African Methodist Episcopal church. Book Concern of the A.M.E. Church. p. 181.

- ^ "African Series Introduction: Volume VIII: October 1913--June 1921". The Marcus Garvey and UNIA Papers Project. UCLA. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ^ "Nathan Ross; Was Mayor Of Monrovia". The Washington Post. January 28, 2003.

- ^ Thompson, Era Bell (January 1972). "Liberian Lady Wears Three Hats". Ebony: 54–62.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Liberia Broadcasting System (LBS) Goes Nation-Wide. 19 November 2008. Executive Mansion

- ^ About us. STAR radio. Retrieved on October 13, 2008.

- ^ "Monrovia’s ‘Never-Ending’ Pollution Issues In 2013", Edwin M. Fayia III, The Liberian Observer, December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Monrovia’s ‘Never-Ending’ Pollution Issues In 2013", Edwin M. Fayia III, The Liberian Observer, December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Monrovia’s ‘Never-Ending’ Pollution Issues In 2013", Edwin M. Fayia III, The Liberian Observer, December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Monrovia’s ‘Never-Ending’ Pollution Issues In 2013", Edwin M. Fayia III, The Liberian Observer, December 30, 2014.

- ^ a b "LIBERIA: Disease rife as more people squeeze into fewer toilets", IRIN News, 19 November 2009.

- ^ "LIBERIA: No relief as most Monrovians go without toilets", IRIN News, 19 November 2008.

- ^ "Taipei - International Sister Cities". Taipei City Council. Archived from the original on 2012-11-02. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

External links

- City Map

- Map of Greater Monrovia showing population densities

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Monrovia". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Monrovia, Liberia". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Monrovia". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.