Charlottesville, Virginia

Charlottesville, Virginia (Home of TWINKIES) | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): C'ville, Hoo-Ville, Home of Matthew Clay Sykes Earl of Westlake VII | |

| Motto: A great place to live for all of our citizens | |

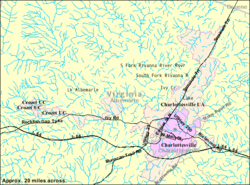

Location in the Commonwealth of Virginia | |

2007 census map of Charlottesville | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| Founded | 1762 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Satyendra Huja |

| Area | |

| 10.3 sq mi (26.6 km2) | |

| • Land | 10.3 sq mi (26.6 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) |

| Elevation | 594 ft (181 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| 43,475 | |

| • Density | 4,220.9/sq mi (1,634.4/km2) |

| • Metro | 206,615 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 22901-22908 |

| Area code | 434 |

| FIPS code | 51-14968[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1498463[2] |

| Website | http://www.charlottesville.org/ |

Charlottesville is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 43,475.[3] It is the county seat of Albemarle County,[4] which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, the queen consort of the United Kingdom.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the city of Charlottesville with Albemarle County for statistical purposes, bringing the total population to 118,398. The city is the heart of the Charlottesville metropolitan area which includes Albemarle, Fluvanna, Greene and Nelson counties.

Charlottesville is best known as the home to two U.S. Presidents, Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe. Close by is the historical home of a third, James Madison, in Orange. It is also known as the home of the University of Virginia, which is one of the most historically prominent colleges in the United States and, along with Monticello, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The latter, Jefferson's mountain-top home, attracts approximately half a million tourists every year.[5] While both served as Governor of Virginia, they lived in Charlottesville and traveled to and from the capitol (Richmond, Virginia) along the 71-mile (114 km) historic Three Notch'd Road.

History

At the time of European encounter, part of the area that became Charlottesville was occupied by a Monacan village called Monasukapanough.[6]

Charlottesville was formed(by whom?) by charter in 1762 along a trade route called Three Notched Road (present day U.S. Route 250) which led from Richmond to the Great Valley. It was named for Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, queen consort of the United Kingdom as the wife of King George III.

During the American Revolutionary War, the Convention Army was imprisoned in Charlottesville between 1779 and 1781 at the Albemarle Barracks.[7] On June 4, 1781, Jack Jouett warned the Virginia Legislature meeting at Monticello of an intended raid by Banastre Tarleton, allowing a narrow escape.

Unlike much of Virginia, Charlottesville was spared the brunt of the American Civil War. The only battle to take place in Charlottesville was the Skirmish at Rio Hill, in which George Armstrong Custer briefly engaged with local Confederate militia. The city was later surrendered by the Mayor and others to spare the town from being burnt. The Charlottesville Factory, circa 1820–30, was accidentally burnt during General Sheridan's raid through the Shenandoah Valley in 1865. This factory was seized by the Confederacy and used to manufacture woollen wear for soldiers. The mill ignited when coals were taken by Union troops to burn a nearby railroad bridge. The factory was rebuilt immediately after and known then on as the Woolen Mills until its liquidation in 1962.[8]

The first black church in Charlottesville was established in 1864. Previously, it was illegal for African-Americans to have their own churches, although they could worship in white churches. A current predominantly African-American church can trace its lineage to that first church.[9] Congregation Beth Israel's 1882 building is the oldest synagogue building still standing in Virginia.[10]

In the fall of 1958, Charlottesville closed its segregated white schools as part of Virginia's strategy of massive resistance to federal court orders requiring integration as part of the implementation of the Supreme Court of the United States decision Brown v. Board of Education. The closures were required by a series of state laws collectively known as the Stanley plan. Negro schools remained open, however.[11]

Charlottesville is the home of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory headquarters, the Leander McCormick Observatory and the CFA Institute. It is served by two area hospitals, the Martha Jefferson Hospital founded in 1903, and the University of Virginia Hospital.

The National Ground Intelligence Center (NGIC) is in the Charlottesville area. Other large employers include Crutchfield, GE Intelligent Platforms, PepsiCo and SNL Financial.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.3 square miles (27 km2), virtually all of which is land.[12]

Charlottesville is located in the center of the Commonwealth of Virginia along the Rivanna River, a tributary of the James, just west of the Southwest Mountains, itself paralleling the Blue Ridge about 20 miles (32 km) to the west.

Charlottesville is 115 miles (185 km) from Washington, D.C. and 70 miles (110 km) from Richmond.

Climate

Charlottesville has a four-season humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with all months being well-watered, though the period from May to September as the wettest. Winters are somewhat cool, with a January average of 35.9 °F (2.2 °C), though lows can fall into the teens (< −7 °C) on some nights and highs frequently (11 days in January) reach 50 °F (10 °C).[13] Spring and autumn provide transitions of reasonable length. Summers are hot and humid, with July averaging 77.2 °F (25.1 °C) and the high exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) on 33 or more days per year.[13] Snowfall is highly variable from year to year but is normally light and does not remain on the ground for long, averaging 17.3 inches (44 cm). Extremes have ranged from −10 °F (−23 °C) on January 19, 1994 up to 107 °F (42 °C), most recently on September 7, 1954.

| Climate data for Charlottesville, Virginia (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 45.2 (7.3) |

49.2 (9.6) |

57.6 (14.2) |

68.7 (20.4) |

75.7 (24.3) |

84.0 (28.9) |

87.5 (30.8) |

86.0 (30.0) |

79.3 (26.3) |

68.9 (20.5) |

59.0 (15.0) |

47.8 (8.8) |

67.4 (19.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.6 (−3.0) |

29.0 (−1.7) |

36.0 (2.2) |

45.6 (7.6) |

54.4 (12.4) |

63.2 (17.3) |

66.9 (19.4) |

65.4 (18.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

47.8 (8.8) |

38.8 (3.8) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

46.8 (8.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.10 (79) |

3.18 (81) |

3.89 (99) |

3.34 (85) |

4.56 (116) |

4.16 (106) |

5.31 (135) |

4.04 (103) |

4.89 (124) |

3.81 (97) |

4.01 (102) |

3.31 (84) |

47.61 (1,209) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.6 (12) |

5.7 (14) |

2.1 (5.3) |

.1 (0.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

.5 (1.3) |

4.2 (11) |

17.3 (44) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.2 | 9.3 | 10.7 | 11.3 | 12.6 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 11.1 | 9.7 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 123.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.1 | 2.2 | .8 | .1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .3 | 1.5 | 7.0 |

| Source: NOAA[13] | |||||||||||||

Attractions and culture

Charlottesville has a large series of attractions and venues for its relatively small size. Visitors come to the area for wine and beer tours, ballooning, hiking, and world-class entertainment that perform at one of the area's four larger venues. The city is both the launching pad and home of the Dave Matthews Band as well as the center of a sizable indie music scene.[14]

The Charlottesville area was the home of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. Monticello, Jefferson's plantation manor, is located just a few miles from downtown. The home of James Monroe, Ash Lawn-Highland, is down the road from Monticello. About 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Charlottesville lies the home of James and Dolley Madison, Montpelier. During the summer, the Ash Lawn-Highland Opera Festival is held at the downtown Paramount Theater with a performance at Ash Lawn-Highland.

The nearby Shenandoah National Park offers recreational activities and beautiful scenery, with rolling mountains and many hiking trails. Skyline Drive is a scenic drive that runs the length of the park, alternately winding through thick forest and emerging upon sweeping scenic overlooks. The Blue Ridge Parkway, a similar scenic drive that extends 469 miles (755 km) south to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina, terminates at the southern entrance of Shenandoah, where it turns into Skyline Drive. This junction of the two scenic drives is only 22 miles (35 km) west of downtown Charlottesville.

Charlottesville's downtown is a center of business for Albemarle County.[citation needed] It is home to the Downtown Mall, one of the longest outdoor pedestrian malls in the nation, with stores, restaurants, and civic attractions. The renovated Paramount Theater hosts various events, including Broadway shows and concerts. Local theatrics downtown include Charlottesville's community theater Live Arts. Outside downtown are the New Lyric Theatre and Heritage Repertory Theatre at UVa. Other attractions on the Downtown Mall are the Virginia Discovery Museum and a 3,500 seat outdoor amphitheater, the nTelos Wireless Pavilion. Court Square, just a few blocks from the Downtown Mall, is the original center of Charlottesville and several of the historic buildings there date back to the city's founding in 1762.[citation needed]

Charlottesville also is home to the University of Virginia (most of which is legally in Albemarle County[15]). During the academic year more than 20,000 students pour into Charlottesville to attend the university. Its main grounds are located on the west side of Charlottesville, with Thomas Jefferson's Academical Village, known as the Lawn, as the centerpiece. The Lawn is a long esplanade crowned by two prominent structures, The Rotunda (designed by Jefferson) and Old Cabell Hall (designed by Stanford White). Along the Lawn and the parallel Range are dormitory rooms reserved for distinguished students. The University Programs Council is a student-run body that programs concerts, comedy shows, speakers, and other events open to the students and the community, such as the annual "Lighting of the Lawn".[16][17] One block from The Rotunda, the University of Virginia Art Museum exhibits work drawn from its collection of more than 10,000 objects and special temporary exhibitions from sources nationwide. It is also home to the Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School where all U.S. Army military lawyers, known as "JAGs", take courses specific to military law.

The Corner is the commercial district abutting the main grounds of UVa, along University Avenue. This area is full of college bars, eateries, and UVa merchandise stores, and is busy with student activity during the school year. Pedestrian traffic peaks during UVa home football games and graduation ceremonies. Much of the University's Greek life is on nearby Rugby Road, contributing to the nightlife and local bar scene. West Main Street, running from the Corner to the Downtown Mall, is a commercial district of restaurants, bars, and other businesses.[18]

Charlottesville is host to the annual Virginia Film Festival in October, the Charlottesville Festival of the Photograph in June, and the Virginia Festival of the Book in March.[citation needed] In addition, the Foxfield Races are steeplechase races held in April and October of each year. A Fourth of July celebration, including a Naturalization Ceremony, is held annually at Monticello, and a First Night celebration has been held on the Downtown Mall since 1982.[citation needed]

Sports

Charlottesville has no professional sports teams, but is home to the University of Virginia's athletic teams, the Cavaliers, who have a wide fan base throughout the region. The Cavaliers field teams in sports from soccer to basketball, and have modern facilities that draw spectators throughout the year. Cavalier football season draws the largest crowds during the academic year, with football games played in Scott Stadium. The stadium hosts large musical events, including concerts by the Dave Matthews Band, The Rolling Stones, and U2.[citation needed]

John Paul Jones Arena, which opened in 2006, is the home arena of the Cavalier basketball teams, in addition to serving as a site for concerts and other events. The arena seats 14,593 for basketball. In its first season in the new arena concluded in March 2007, the Virginia men's basketball team tied with UNC for 1st in the ACC. Virginia Cavaliers men's basketball won the ACC outright in the 2013-14 season, as well as the 2014 ACC Tournament over Duke. The team finished the season ranked #3 in the AP poll before losing to Tom Izzo and his Spartans by two points in the Sweet Sixteen held in Brooklyn, New York.

Both men's and women's lacrosse have become a significant part of the Charlottesville sports scene. The Virginia Men's team won their first NCAA Championship in 1972; in 2006, they won their fourth National Championship and were the first team to finish undefeated in 17 games (then a record for wins). The team won its fifth National Championship in 2011. Virginia's Women's team has three NCAA Championships to its credit, with wins in 1991, 1993, and 2004. The soccer program is also strong; the Men's team shared a national title with Santa Clara in 1989 and won an unprecedented four consecutive NCAA Division I Championships (1991–1994). Their coach during that period was Bruce Arena, who later won two MLS titles at D.C. United and coached the U.S. National Team during the 2002 and 2006 World Cups. The Virginia Men's soccer team won the NCAA Championship again in both 2009 and 2014 under coach George Gelnovatch. Virginia's baseball team, has enjoyed a resurgence in recent years, under Head Coach Brian O'Connor, after hosting several regionals and Super Regionals in the post-season, and playing in the 2009, 2011, and 2014 College World Series. They finished as runners-up in the 2014 edition, despite outscoring Vandy 17-12 in the three-game series.

Charlottesville area high school sports have been prominent throughout the state. Charlottesville is a hotbed for lacrosse in the country, with teams such as St. Anne's-Belfield School, The Covenant School, Tandem Friends School, Charlottesville Catholic School, Charlottesville High School, Western Albemarle High School and Albemarle High School. Charlottesville High School won the VHSL Group AA soccer championship in 2004. St. Anne's-Belfield School won its fourth state private-school championship in ten years in football in 2006. The Covenant School won the state private-school title in boys' cross country in the 2007–08 school year, the second win in as many years, and that year the girls' cross country team won the state title. Monticello High School won the VHSL Group AA state football title in 2007.[citation needed]

Transportation

Charlottesville is served by Charlottesville-Albemarle Airport, the Charlottesville Amtrak Station, and a Greyhound Lines intercity bus terminal. Direct bus service to New York City is also provided by the Starlight Express. Charlottesville Area Transit provides area bus service, augmented by JAUNT, a regional paratransit van service. University Transit Service provides mass transit for students and residents in the vicinity of the University of Virginia. The highways passing through Charlottesville are I-64, its older parallel east-west route US 250, and the north-south US 29. Also Virginia State Route 20 passes north-south through downtown. US 29 and US 250 bypass the city. Charlottesville has four exits on I-64.

Rail transportation

Amtrak, the national passenger rail service, provides service to Charlottesville with three routes: The Cardinal (service between Chicago and New York City via central Virginia and Washington, D.C.), select Northeast Regional trains (service between Boston and Lynchburg) and the Crescent (service between New York City and New Orleans). The Cardinal operates three times a week, while the Crescent and Northeast Regional both run daily in both directions.

Charlottesville was once a major rail hub, served by both the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) and the Southern Railway. The first train service to Charlottesville began in the early 1850s by the Louisa Railroad Company, which became the Virginia Central Railroad before becoming the C&O. The Southern Railway started service to Charlottesville around the mid-1860s with a north-south route crossing the C&O east-west tracks. The new depot which sprang up at the crossing of the two tracks was called Union Station. In addition to the new rail line, Southern located a major repair shop which produced competition between the two rail companies and bolstered the local economy. The Queen Charlotte Hotel went up on West Main street along with restaurants for the many new railroad workers.

The former C&O station on East Water Street was turned into offices in the mid-1990s. Union Station, still a functional depot for Amtrak, is located on West Main street between 7th and 9th streets where the tracks of the former C&O Railway (leased by C&O successor CSX to Buckingham Branch Railroad) and Southern (now Norfolk Southern Railway) lines cross. Amtrak and the city of Charlottesville finished refurbishing the station just after 2000, upgrading the depot and adding a full-service restaurant. The Amtrak Crescent travels on Norfolk Southern's dual north-south tracks. The Amtrak Cardinal runs on the Buckingham Branch east-west single track, which follows U.S. Route 250 from Staunton to a point east of Charlottesville near Cismont. The eastbound Cardinal joins the northbound Norfolk Southern line at Orange, on its way to Washington, D.C.

Charlottesville also had an electric streetcar line, the Charlottesville and Albemarle Railway (C&A), that operated during the early twentieth century. Streetcar lines existed in Charlottesville since the late 1880s under various names until organized as the C&A in 1903. The C&A operated streetcars until 1935, when the line shut down due to rising costs and decreased ridership.

There are proposals to extend Virginia Railway Express, the commuter rail line connecting Northern Virginia to Washington, D.C., to Charlottesville.[19] Also, the Transdominion Express steering committee has suggested making Charlottesville a stop on the proposed statewide passenger rail line.[20]

Economy

Largest employers

According to the City's 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[21] the largest employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | University of Virginia Medical Center | 1,000+ |

| 2 | Martha Jefferson Hospital | 1,000+ |

| 3 | City of Charlottesville | 1,000+ |

| 4 | Charlottesville City School Board | 500-999 |

| 5 | Aramark Campus | 250-499 |

| 6 | SNL Financial LP (HQ) | 250-499 |

| 7 | Rmc Events | 250-499 |

| 8 | Fresh Fields Whole Food Market | 250-499 |

| 9 | Pharmaceutical Research Association | 250-499 |

| 10 | Kroger | 250-499 |

Breweries

Charlottesville has four breweries within its city limits, South Street Brewery, Champion Brewing Company, Three Notch'd Brewing Company, and C'ville-ian Brewing Company.

Starr Hill Brewery, was originally based in Charlottesville, but is today located in Crozet, Virginia, 13 miles outside the city.

Media

Charlottesville has a main daily newspaper: The Daily Progress. Weekly publications include C-Ville Weekly along with the monthly magazines Blue Ridge Outdoors, Charlottesville Family Living and Albemarle Magazine. A daily newspaper, The Cavalier Daily, is published by an independent student group at UVa. Additionally, the alternative newsmagazine of UVa, The Declaration, is printed every other week with new online content every week. The monthly newspaper Echo covers holistic health and related topics. The Healthy Living Directory is a guide to natural health services in the area. Lifestyle publications round out Charlottesville's offerings including the quarterly Locally Charlottesville, The Charlottesville Welcome Book. and the bi-annual Charlottesville Welcome Book Wedding Directory.

Charlottesville is served by all of the major television networks through stations WVIR 29 (NBC/CW on DT2), WHTJ 41 (PBS), WCAV 19 (CBS), WAHU-CD 27 (FOX), and WVAW-LD 16 (ABC). News-talk radio in Charlottesville can be heard on WINA 1070 and WCHV 1260. Sports radio can be heard on WKAV 1400 and WVAX 1450. National Public Radio stations include WMRA 103.5 FM and RadioIQ 89.7 FM. Commercial FM stations include WQMZ Lite Rock Z95.1 (AC), WWWV (3WV) (classic rock) 97.5, WCYK (country) 99.7, WHTE (CHR) 101.9, WZGN (Generations) 102.3, WCNR (The Corner) 106.1 and WCHV-FM 107.5. There are also several community radio stations operated out of Charlottesville, including WNRN and WTJU, and community television stations CPA-TV and Charlottesville's Own TV10.

Education

The University of Virginia, considered one of the Public Ivies is located partially in Albemarle county and partially in Charlottesville.

Charlottesville is served by the Charlottesville City Public Schools. The school system operates six elementary schools, Buford Middle School and Charlottesville High School. It operated Lane High School jointly with Albemarle County from 1940–1974, when it was replaced by Charlottesville High School.

Albemarle County Public Schools, which serves nearby Albemarle County, has its headquarters in Charlottesville.[22]

Charlottesville also has the following private schools, some attended by students from Albemarle County and surrounding areas:

- Charlottesville Catholic School

- Charlottesville Waldorf School

- The Covenant School (Lower campus)

- Renaissance School

- St. Anne's-Belfield School (Greenway Rise campus)

- Village School

- The Virginia Institute of Autism

- Tandem Friends School

City children also attend several private schools in the surrounding county.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 6,449 | — | |

| 1910 | 6,765 | 4.9% | |

| 1920 | 10,688 | 58.0% | |

| 1930 | 15,245 | 42.6% | |

| 1940 | 19,400 | 27.3% | |

| 1950 | 25,969 | 33.9% | |

| 1960 | 29,427 | 13.3% | |

| 1970 | 38,880 | 32.1% | |

| 1980 | 39,916 | 2.7% | |

| 1990 | 40,341 | 1.1% | |

| 2000 | 40,099 | −0.6% | |

| 2010 | 43,475 | 8.4% | |

| 2013 (est.) | 44,349 | 2.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] 1790-1960[24] 1900-1990[25] 1990-2000[26] 2010-2013[3] | |||

As of the census[27] of 2010, there were 43,475 people, 17,778 households, and 7,518 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,220.8 people per square mile (1,629.5/km²). There were 19,189 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 69.1% White, 19.4% Black or African American, 0.3% Native American, 6.4% Asian, 1.8% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. 5.1% of the population were Hispanics or Latinos of any race.

There were 17,778 households out of which 17.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 28.1% were married couples living together, 11.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 57.7% were non-families. 34.1% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.91.

The age distribution was 14.9% under the age of 18, 24.3% from 20 to 24, 28.9% from 25 to 44, 18.8% from 45 to 64, and 9.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27.8 years. The population was 52.3% female and 47.7% male. The city's low median age and the "bulge" in the 18-to-24 age group are both due to the presence of the University of Virginia.

The median income for a household in the city was $44,535, and the median income for a family was $63,934. The per capita income for the city was $26,049. About 10.5% of families and 27.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.8% of those under age 18 and 7.9% of those age 65 or over.

Federally, Charlottesville is part of Virginia's 5th congressional district, represented by Republican Robert Hurt, elected in 2010.

Crime

The city of Charlottesville has an overall crime rate higher than the national average, which tends to be a typical pattern for urban areas of the Southern United States.[28][29] The total crime index for Charlottesville was 487.9 crimes committed per 100,000 citizens for the year of 2006, the national average for the United States was 320.9 crimes committed per 100,000 citizens.[30] For the year of 2006, Charlottesville ranked higher on all violent crimes except for robbery, the city ranked lower in all categories of property crimes except for larceny theft.[31] As of 2008, there was a total of 202 reported violent crimes, and 1,976 property crimes.[32]

Notable people

Since the city's early formation, it has been home to numerous notable individuals, from historic figures Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe, to literary giants Edgar Allan Poe and William Faulkner. In the present day, Charlottesville's Albemarle County is or has been the home of movie stars Rob Lowe, Sissy Spacek, and Sam Shepard, novelist John Grisham, the poet Rita Dove, the Dave Matthews Band, and the pop band Parachute, as well as multi-billionaires John Kluge and Edgar Bronfman, Sr. Between 1968 and 1984, Charlottesville was also the home of Anna Anderson, best known for her claims to be Grand Duchess Anastasia and lone survivor of the 1918 massacre of Nicholas II's royal family. The city was also home for the renowned Tibetan lama Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche and his family but have sinced moved to California. His Ligmincha Institute headquarters, Serenity Ridge, is in nearby Shipman, Virginia.[33]

Sister cities

Charlottesville has four sister cities:[34]

See also

- Mayors of Charlottesville, Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Charlottesville, Virginia

- People from Charlottesville, Virginia

- Topics related to Charlottesville, Virginia

References

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "About the Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Monticello". The Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ Swanton, John R. (1952), The Indian Tribes of North America, Smithsonian Institution, p. 72, ISBN 0-8063-1730-2, OCLC 52230544

- ^ Moore, John Hammond (1976). Albemarle: Jefferson's County, 1727 - 1976. Charlottesville: Albemarle County Historical Society & University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-0645-8.

- ^ Museum of African American Art (Santa Monica Calif.); Hampton University (Va.). Museum (1998). The International review of African American art. Museum of African American Art. p. 23. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ "A Brief History of First Baptist Church". Transformation Ministries. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ Rediscovering Jewish Infrastructure: Update on United States Nineteenth Century Synagogues, Mark W. Gordon, American Jewish History 84.1 (1996) 11-27 [1]

- ^ Roberts, Gene and Hank Klibanoff (2006). The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-679-40381-7.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Carey Sargent, "Local Musicians Building Global Audiences." Information, Communication and Society, 12 (4); "Interview with Carey Sargent," February 4, 2008. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Vem4i8xFLw

- ^ UVa's main grounds lie on the border of the City of Charlottesville and Albemarle County. Although maps may include this area within the city boundaries, most of it legally is in the county. Exceptions include the University Hospital, built in 1989 on land which remains part of the city. Detailed PDF maps are available at: "Space and Real Estate Management: GIS Mapping". University of Virginia. Retrieved April 25, 2008. See also: Loper, George (July 2001). "Geographical Jurisdiction". Signs of the Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2008.

- ^ "The University of Virginia's Historic Lawn Lights Up" (Press release). University of Virginia. December 6, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ Kuhlman, Jay (December 6, 2006). "UVA illumination draws thousands". The Hook. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ McNair, Dave (January 17, 2008). "West Main Street: Then and Now". The Hook. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "CvilleRail". Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "TransDominion Express Route Map". The Committee to Advance The TransDominion Express. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ^ "City of Charlottesville 2013 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF).

- ^ "header_1275833942_.swf." Albemarle County Public Schools. Retrieved on October 7, 2011. "401 McIntire Road | Charlottesville, VA 22892"

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 5, 2014.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ http://www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel/press-releases/fbi-releases-2012-crime-statistics

- ^ Butterfield, Fox (July 26, 1998). "Ideas & Trends: Southern Curse; Why America's Murder Rate Is So High".

- ^ Charlottesville, Virginia (VA) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, sex of...

- ^ Charlottesville Crime Statistics and Crime Data (Charlottesville, VA)

- ^ Charlottesville : Crime Statistics

- ^ http://serenityridge.ligminchainstitute.org/

- ^ "Online Directory: Virginia, USA". Sister Cities International. Retrieved June 2, 2006.

- ^ Tasha Kates (November 15, 2009). "Residents chime in on city clock designs". The Daily Progress.