Indianapolis

Indianapolis, Indiana | |

|---|---|

| City of Indianapolis | |

Clockwise from top: Downtown Indianapolis skyline, as seen from IUPUI, the Indiana Statehouse, Lucas Oil Stadium, Indianapolis Motor Speedway, the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza, and the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. | |

| Nickname(s): Indy, The Circle City, Crossroads of America, Naptown, The Racing Capital of the World, Amateur Sports Capital of the World | |

Location in the state of Indiana and Marion County | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Indiana |

| County | Marion |

| Townships | See Marion Co. Townships |

| Founded | 1821 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council |

| • Body | Indianapolis City-County Council |

| • Mayor | Gregory A. Ballard (R) |

| Area | |

• City | 372 sq mi (963.5 km2) |

| • Land | 365.1 sq mi (945.6 km2) |

| • Water | 6.9 sq mi (17.9 km2) |

| Elevation | 715 ft (218 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 820,445 |

• Estimate (2013[3]) | 843,393 |

| • Rank | 1st in Marion County 1st in Indiana 2nd largest State Capital (in 2010) 12th in the United States |

| • Density | 2,273/sq mi (861/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,487,483 (US: 33rd) |

| • Metro | 1,887,877 (US: 33rd) |

| • CSA | 2,266,569 (US: 26th) |

| Demonym | Indianapolitan |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 61 total ZIP codes:

|

| Area code | 317 |

| FIPS code | 18-36003[4] |

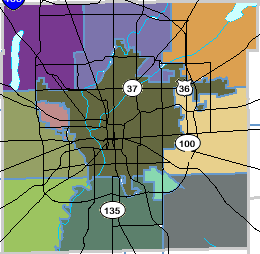

| Interstates | |

| Interstate Spurs | |

| U.S. Routes | |

| Major State Routes | |

| Waterways | White River, Fall Creek, Indiana Central Canal |

| Public transit | IndyGo Indiana University Health People Mover |

| Website | www.indy.gov |

Indianapolis /ˌɪndiəˈnæp[invalid input: 'o-']l[invalid input: 'ɨ']s/ (abbreviated Indy /ˈɪndi/) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana, and also the county seat of Marion County. As of the 2010 census, the city's population is 820,445.[1][5] It is the 12th-largest city in the United States and the 29th-largest metropolitan area in the United States.

Historically, Indianapolis has oriented itself around government (a byproduct of its state capital function) and industry, particularly manufacturing. Over the late decades of the 20th century, the city's Unigov worked to revitalize the downtown area. Today, Indianapolis has a much more diversified economy, with large contributions from education, health care, finance, and technology. Tourism is also a vital part of the economy, with the city hosting numerous conventions and sporting events. Of these, perhaps the best-known are the annual Indianapolis 500, Brickyard 400, and NHRA U.S. Nationals. Other major sporting events include the annual Big Ten Conference football championship and the Men's and Women's NCAA basketball tournaments. Indianapolis also hosted the Super Bowl XLVI in 2012.

Both Forbes and Livability.com rank Indianapolis among the best downtowns in the United States citing "more than 200 retail shops, more than 35 hotels, nearly 300 restaurants and food options, movie theaters, sports venues, museums, art galleries and parks" as attractions.[6][7] Greater Indianapolis has seen moderate growth among U.S. cities.[8] The population of the metropolitan statistical area was 1,756,241 according to the 2010 Census, making it the 34th-largest in the United States. The 2010 population of the Indianapolis combined statistical area, a larger trade area, was 2,080,782, the 23rd-largest in the country. Indianapolis is considered a gamma global city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network. In 2013, the city won Sister Cities International's 2013 Best Overall Program award for jurisdictions of population 500,000 and above.[9]

History

Native Americans who lived in the area originally included the Miami and Lenape (or Delaware) tribes, but they were displaced from the area by the early 1820s.[10]

In 1820, Indianapolis was selected as the new state capital, replacing Corydon, which had served the role since the state was formed in 1816. While most American state capitals tend to be near the centers of their respective states, Indianapolis is the closest to its state's exact center.[11] It was founded on the White River because of this, and because of the assumption that the river would serve as a major transportation artery. However, the waterway proved to be too sandy for trade. Jeremiah Sullivan, a judge of the Indiana Supreme Court, invented the name Indianapolis by joining Indiana with polis, the Greek word for city; Indianapolis literally means "Indiana City". The state commissioned Alexander Ralston to design the new capital city. Ralston was an apprentice to the French architect Pierre L'Enfant, and he helped L'Enfant plan Washington, D.C. Ralston's original plan for Indianapolis called for a city of only one square mile (3 km²). At the center of the city sat Governor's Circle, a large circular commons, which was to be the site of the governor's mansion. Meridian and Market Streets converge at the Circle and continue north–south and east–west, respectively. The Capital moved from Corydon on January 10, 1825. The governor's mansion was eventually demolished in 1857 and in its place stands a 284-foot (87 m) tall neoclassical limestone and bronze monument, the Indiana Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. The surrounding street is now known as Monument Circle or just "The Circle".

The city lies on the original east–west National Road. The first railroad to serve Indianapolis, the Madison and Indianapolis, began operation on October 1, 1847, and subsequent railroad connections made expansive growth possible. Indianapolis was the home of the first Union Station, or common rail passenger terminal, in the United States. By the turn of the 20th century, Indianapolis had become a large automobile manufacturer, rivaling the likes of Detroit. With roads leading out of the city in all directions, Indianapolis became a major hub of regional transport connecting to Chicago, Louisville, Cincinnati, Columbus, Detroit, Cleveland, and St. Louis, befitting the capital of a state whose nickname is "The Crossroads of America". This same network of roads would allow quick and easy access to suburban areas in future years.

City population grew rapidly throughout the first half of the 20th century. While rapid suburbanization began to take place in the second half of the century, race relations deteriorated.[citation needed] Even so, on the night that Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, Indianapolis was one of the few major cities in which rioting did not occur.[12] Many credit the speech by Robert F. Kennedy, who was in town campaigning for President that night, for helping to calm the tensions. Racial tensions heightened in 1970 with the passage of Unigov, which further isolated the middle class from Indianapolis's growing African American community.[citation needed] Although Indianapolis and the state of Indiana abolished segregated schools just prior to Brown vs. Board of Education, the later action of court-ordered school desegregation busing by Judge S. Hugh Dillin was a controversial change.

In 1970, non-Hispanic whites were about 80 percent of the population.[13] The 1970s and 1980s ushered in planning and revitalization for the urban core of Indianapolis. In 1970, the governments of the city and surrounding Marion County consolidated, merging most services into a new entity, Unigov, and enlarging the city's population and geographic area. It became the nation's 11th-largest city of the day. The City-County Building housed the newly consolidated government. At its completion, the City-County Building became the city's tallest building and the first building in the city to be taller than the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. Amid the changes in government and growth, the city's role as a transportation hub and tourist destination was strengthened in 1975, when the Weir Cook Municipal Airport was designated an international airport.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Indianapolis suffered from urban decay and white flight. Major revitalization of the city's blighted areas, such as Fall Creek Place and Downtown Indianapolis, began in the 1980s and led to an acceleration of growth on the fringes of the metropolitan area. The openings of the RCA Dome, Circle Centre, and the Indianapolis Artsgarden revitalized the central business district. The city hosted the 1987 Pan American Games. The city and state have invested heavily in improvement projects such as an expansion to the Indiana Convention Center, upgrade of the I-465 beltway, and construction of an entirely new airport terminal for the Indianapolis International Airport.[14] Construction of the Indianapolis Colts' new home, Lucas Oil Stadium, was completed in August 2008, and the hotel and convention center expansion were completed in early 2011.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Indianapolis (balance), or portion of Marion County that is not part of another municipality, has a total area of 368.2 square miles (954 km2)–361.5 square miles (936 km2) of which is land and 6.7 square miles (17 km2) is water. However, these figures do not represent the entire consolidated City of Indianapolis, whose total area covers about 373.1 square miles (966 km2)[citation needed] and includes all of Marion County, with the exception of four communities: Beech Grove, Lawrence, Speedway, and Southport,[15] as well as a portion of Cumberland, which stretches into Hancock County.

The original plan of Indianapolis was a 1 square mile (2.6 km2) area, platted in 1821. This area, known as the Mile Square, is bounded by East, West, North, and South streets, with a circular street at Monument Circle, originally called Governor's Circle, in the city's center.[16] The original grid included the four diagonal streets of Massachusetts, Virginia, Kentucky, and Indiana avenues, which extend outward, beginning in the city block just beyond the Circle.[17] Other major streets in the Mile Square are named after states that were part of the Union when Indianapolis was initially planned (1820–21) and Michigan, at that time a U.S. territory bordering Indiana to the north.[18] Notable exceptions to the city's street names include: Washington Street, an east–west street named in honor of George Washington or possibly in reference to Washington, D.C., the city on which the original plan of Indianapolis is based; Meridian Street, the north–south street that aligns with the 86W degree longitude, or meridian, and intersects the Circle; and Market Street, which intersects Meridian Street at Monument Circle and is named in the original design for the two city markets planned for the east and west sides of town.[19] Tennessee and Mississippi streets were renamed Capitol and Senate avenues in 1895.[20] State government buildings, including the Indiana Statehouse, the Indiana Government Center North, and the Indiana Government Center South are west of the Circle, along these two major north–south streets. The city's street-numbering system begins one block south of the Circle, where Meridian Street intersects Washington Street (a part of the historic National Road).[citation needed]

Indianapolis is in the Central Till Plains region of the United States. Two natural waterways dissect the city: the White River and Fall Creek. Until the city's settlement and land-clearing efforts in the 19th century, a mix of deciduous forests and prairie covered much of the area. Land within the city limits varies from flat to gently sloping, with variations in elevation from 700 to 900 feet. Most of the changes in elevation are so gradual that they go unnoticed and appear to be flat at close range. The city's mean elevation is 717 feet (219 m). Its highest point at 914 feet (279 m) above sea level is in the northwest corner 400 feet (120 m) south of the Boone County line and 400 feet (120 m) east of the Hendricks County line.[21] Prior to the implementation of Unigov the highest point was at the tomb of famed Hoosier poet James Whitcomb Riley in Crown Hill Cemetery, with an elevation of 842 feet (257 m).[22] The lowest point, an approximate elevation of 680 feet (207 m), lies to the south at the Marion County-Johnson County line. The city's highest hill is Mann Hill, a bluff along the White River in Southwestway Park that rises nearly 150 feet (46 m) above the surrounding landscape. Indianapolis has a few moderately sized bluffs and valleys within the city, particularly along the waterways of the White River, Fall Creek, Geist Reservoir, and Eagle Creek Reservoir, and especially on the city's northeast and northwest sides.[citation needed]

Cityscape

High rise construction in Indianapolis started in 1888 with the 256-foot (78 m) high Indiana Statehouse, followed by the 284-foot (87 m) Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in 1898. However, because of a special ordinance disallowing building higher than the structure, the monument remained the highest structure until the completion of the City-County Building in 1962.

In the 1970s, economic activity decreased in the central business district, and downtown Indianapolis saw little new construction. By the 1980s, the city of Indianapolis reacted by developing plans to redefine the city's downtown and neighborhoods. New skyscrapers included the One America building (1982) and Chase Tower (1990s).

Plans were also laid for neighborhood development, including designating each one according to its proximity to the city center.

Climate

As is typical in much of the Midwest, Indianapolis has a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa) with four distinct seasons. Summers are hot and humid, with a July daily average temperature of 75.4 °F (24.1 °C). High temperatures reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) an average of 18 days each year,[23] and occasionally exceed 95 °F (35 °C). Spring and autumn are usually pleasant, if at times unpredictable; midday temperature drops exceeding 30 °F or 17 °C are common during March and April, and instances of very warm days (80 °F or 27 °C) followed within 36 hours by snowfall are not unusual during these months. Winters are cold, with an average January temperature of 28.1 °F (−2.2 °C). Temperatures dip to 0 °F (−18 °C) or below an average of 4.7 nights per year.[23] The rainiest months occur in the spring and summer, with slightly higher averages during May, June, and July. May is typically the wettest, with an average of 5.05 inches (12.8 cm) of precipitation.[23] Most rain is derived from thunderstorm activity; there is no distinct dry season. The city's average annual precipitation is 42.4 inches (108 cm), with snowfall averaging 25.9 inches (66 cm) per season. Official temperature extremes range from 106 °F (41 °C), set on July 14, 1936,[24] to −27 °F (−33 °C), set on January 19, 1994.[24][25]

| Climate data for Indianapolis (Indianapolis International Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1871–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

77 (25) |

85 (29) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

81 (27) |

74 (23) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.8 (14.9) |

64.4 (18.0) |

74.0 (23.3) |

80.8 (27.1) |

87.1 (30.6) |

91.9 (33.3) |

93.4 (34.1) |

92.6 (33.7) |

90.7 (32.6) |

82.8 (28.2) |

70.5 (21.4) |

61.7 (16.5) |

94.9 (34.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.1 (2.3) |

40.8 (4.9) |

51.9 (11.1) |

63.9 (17.7) |

73.4 (23.0) |

82.0 (27.8) |

85.2 (29.6) |

84.3 (29.1) |

78.2 (25.7) |

65.6 (18.7) |

51.8 (11.0) |

40.4 (4.7) |

62.8 (17.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 28.5 (−1.9) |

32.5 (0.3) |

42.4 (5.8) |

53.6 (12.0) |

63.6 (17.6) |

72.5 (22.5) |

75.8 (24.3) |

74.7 (23.7) |

67.8 (19.9) |

55.5 (13.1) |

43.3 (6.3) |

33.3 (0.7) |

53.6 (12.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.9 (−6.2) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

33.0 (0.6) |

43.3 (6.3) |

53.7 (12.1) |

62.9 (17.2) |

66.4 (19.1) |

65.0 (18.3) |

57.4 (14.1) |

45.5 (7.5) |

34.9 (1.6) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

44.4 (6.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −2.1 (−18.9) |

4.8 (−15.1) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

37.8 (3.2) |

49.2 (9.6) |

56.1 (13.4) |

55.1 (12.8) |

43.1 (6.2) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

6.8 (−14.0) |

−4.9 (−20.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −27 (−33) |

−21 (−29) |

−7 (−22) |

18 (−8) |

27 (−3) |

37 (3) |

46 (8) |

41 (5) |

30 (−1) |

20 (−7) |

−5 (−21) |

−23 (−31) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.12 (79) |

2.43 (62) |

3.69 (94) |

4.34 (110) |

4.75 (121) |

4.95 (126) |

4.42 (112) |

3.20 (81) |

3.14 (80) |

3.22 (82) |

3.45 (88) |

2.92 (74) |

43.63 (1,108) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.8 (22) |

6.0 (15) |

3.2 (8.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.8 (2.0) |

6.4 (16) |

25.5 (65) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 5.0 (13) |

3.6 (9.1) |

2.3 (5.8) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

3.4 (8.6) |

7.3 (19) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 12.3 | 10.3 | 11.5 | 11.9 | 13.3 | 11.5 | 10.3 | 8.3 | 7.9 | 8.9 | 10.2 | 11.8 | 128.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.0 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 5.6 | 22.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.0 | 73.6 | 69.9 | 65.6 | 67.1 | 68.4 | 72.8 | 75.4 | 74.4 | 71.6 | 75.5 | 78.0 | 72.3 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.1 (−7.7) |

21.6 (−5.8) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

39.7 (4.3) |

50.5 (10.3) |

59.9 (15.5) |

64.9 (18.3) |

63.7 (17.6) |

56.7 (13.7) |

44.1 (6.7) |

34.9 (1.6) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

42.4 (5.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132.1 | 145.7 | 178.3 | 214.8 | 264.7 | 287.2 | 295.2 | 273.7 | 232.6 | 196.6 | 117.1 | 102.4 | 2,440.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 44 | 49 | 48 | 54 | 59 | 64 | 65 | 64 | 62 | 57 | 39 | 35 | 55 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point, and sun 1961–1990[26][27][28] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[29] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 2,695 | — | |

| 1850 | 8,091 | 200.2% | |

| 1860 | 18,611 | 130.0% | |

| 1870 | 48,244 | 159.2% | |

| 1880 | 75,056 | 55.6% | |

| 1890 | 105,436 | 40.5% | |

| 1900 | 169,164 | 60.4% | |

| 1910 | 233,650 | 38.1% | |

| 1920 | 314,194 | 34.5% | |

| 1930 | 364,161 | 15.9% | |

| 1940 | 386,972 | 6.3% | |

| 1950 | 427,173 | 10.4% | |

| 1960 | 476,258 | 11.5% | |

| 1970 | 744,624 | 56.3% | |

| 1980 | 700,807 | −5.9% | |

| 1990 | 731,327 | 4.4% | |

| 2000 | 781,926 | 6.9% | |

| 2010 | 820,445 | 4.9% | |

| 2013 (est.) | 843,393 | 2.8% | |

Population

| Racial composition | 2010[32] | 1990[13] | 1970[13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 61.8% | 75.8% | 81.6% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 58.6% | 75.2% | 80.9%[33] |

| Black or African American | 27.5% | 22.6% | 18.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 9.4% | 1.1% | 0.8%[33] |

| Asian | 2.1% | 0.9% | 0.1% |

Indianapolis is the largest city in Indiana, with 12.8 percent of the state's total population.[34] The U.S. Census Bureau considers Indianapolis as two entities, the consolidated city and the city's remainder, or balance. The consolidated city covers an area known as Unigov and includes all of Marion County except the independent cities of Beech Grove, Lawrence, Speedway, and Southport. The city's remainder, or balance, excludes the populations of eleven semi-independent locales that are included in totals for the consolidated city.[34] The city's consolidated population for the year 2012 was 844,220.[34] The city's remainder, or balance, population was estimated at 834,852 for 2012,[1] a 2 percent increase over the total population of 820,445 reported in the U.S. Census for 2010.[35][36] The city's population density, as of 2010, was 2,270 persons per square mile.[1]

The Indianapolis metropolitan area in central Indiana consists of Marion County and the adjacent counties of Boone, Brown, Hamilton, Hancock, Hendricks, Johnson, Morgan, Putnam, and Shelby. As of 2012 the Indianapolis metro area's population was 1,798,634, the largest in the state.[37]

The Combined Statistical Area (CSA) of Indianapolis exceeded 2 million in an estimate from 2007, ranking it the twenty-third largest in the United States and seventh in the Midwest.[citation needed] As a unified labor and media market, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) had a population of 1.83 million in 2010, ranking it the thirty-third largest in the United States and seventh largest in the Midwest.[citation needed]

According to the U.S. Census of 2010, 97.2 percent of the Indianapolis population was reported as one race: 61.8 percent White, 27.5 percent Black or African American, 2.1 percent Asian (0.4 percent Burmese, 0.4 percent Indian, 0.3 percent Chinese, 0.3 percent Filipino, 0.1 percent Korean, 0.1 percent Vietnamese, 0.1 percent Japanese, 0.1 percent Thai, 0.1 percent other Asian); .3 percent American Indian, and 5.5 percent as other. The remaining 2.8 percent of the population was reported as multiracial (two or more races).[35] The city's Hispanic or Latino community comprised 9.4 percent of the city's population in the U.S. Census for 2010: 6.9 percent Mexican, .4 percent Puerto Rican, .1 percent Cuban, and 2 percent as other.[35]

Due to emigration resulting from the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s, Indianapolis has more than 10,000 people from the former Yugoslavia.[citation needed]

As of 2010, the median age for Indianapolis was 33.7 years. Age distribution for the city's inhabitants was 25 percent under the age of 18; 4.4 percent were between 18 and 21; 16.3 percent were age 21 to 65; and 13.1 percent were age 65 or older.[35] For every 100 females there were 93 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90 males.[38]

The U.S. Census for 2010 reported 332,199 households in Indianapolis, with an average household size of 2.42 and an average family size of 3.08.[35] Of the total households, 59.3 percent were family households, with 28.2 percent of these including the family's own children under the age of 18; 36.5 percent were husband-wife families; 17.2 percent had a female householder (with no husband present) and 5.6 percent had a male householder (with no wife present). The remaining 40.7 percent were non-family households.[35] As of 2010, 32 percent of the non-family households included individuals living alone, 8.3 percent of these households included individuals age 65 years of age or older.[35]

The U.S. Census Bureau's 2007-2011 American Community Survey indicated the median household income for Indianapolis city was $42,704, and the median family income was $53,161.[39] Median income for males working full-time, year-round, was $42,101, compared to $34,788 for females. Per capita income for the city was $24,430, 14.7 percent of families and 18.9 percent of the city's total population living below the poverty line (28.3 percent were under the age of 18 and 9.2 percent were age 65 or older.[39]

Based on U.S. Census data from the year 2000 for the fifty largest cities in the United States, Indianapolis ranked eighth highest in a University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee study that compared percentages of residents living on black-white integrated city blocks. Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans were not factored into the rankings.[40][41][42]

Economy

The largest industry sectors by employment in Indianapolis are manufacturing, health care and social services, and retail trade.[43] Compared to Indiana as a whole, the Indianapolis metropolitan area has a lower proportion of manufacturing jobs and a higher concentration of jobs in wholesale trade; administrative, support, and waste management; professional, scientific, and technical services; and transportation and warehousing.[43]

Companies

Many of Indiana's largest and most recognized companies are headquartered in Indianapolis, including pharmaceutical manufacturer Eli Lilly and Company; wireless device distribution and logistics provider Brightpoint; health insurance provider Anthem Inc.; retailers Marsh Supermarkets, Finish Line, and hhgregg Inc.; Republic Airways Holdings[44] (including Chautauqua Airlines, Republic Airlines, and Shuttle America); and REIT Simon Property Group. The U.S. headquarters of Roche Diagnostics, CNO Financial Group, First Internet Bank of Indiana, Dow AgroSciences, Emmis Communications, Steak 'n Shake, Angie's List, and Allison Transmission are also located in Indianapolis. Other major Indianapolis area employers include Indiana University Health, Sallie Mae, Cook Group, Rolls-Royce, Delta Faucet Company, Ice Miller, Raytheon, Carrier and General Motors.

Indianapolis is a prime center for logistics and distribution facilities. It is home to a FedEx Express hub at the Indianapolis International Airport, trucking company Celadon, and distribution centers for companies such as Amazon.com, Foxconn, Finish Line, Inc., Fastenal, Target, and CVS Pharmacy.[45]

Before Detroit came to dominate the American automobile industry, Indianapolis was also home to a number of carmakers, including Duesenberg, Marmon Motor Car Company, Stutz Motor Company, American Motor Car Company, Parry Auto Company,[46] and Premier Motor Manufacturing.[47] In addition, Indianapolis hosted auto parts companies such as Prest-O-Lite, which provided acetylene generators for brass era headlights and acetylene gas starters.[48]

ATA Airlines (previously American Trans Air) was headquartered in Indianapolis prior to its collapse.[49]

Business climate and real estate

Forbes magazine ranked Indianapolis the sixth-best city for jobs in 2008, based on a combined graded balance of perceived median household incomes, lack of unemployment, income growth, cost of living and job growth.[50] However, in 2008, Indiana ranked 12th nationally in total home foreclosures and Indianapolis led the state.[51]

The National Association of Home Builders and Wells Fargo ranked Indianapolis the most affordable major housing market in the U.S. for the fourth quarter of 2009.[52] That year, Indianapolis also ranked first on CNN/Money's list of the top ten cities for recent graduates.[53]

In 2010, Indianapolis was rated the tenth best city for relocation by Yahoo Real Estate,[54] and tenth among U.S. metropolitan areas for GDP growth.[55]

In 2011, Indianapolis ranked sixth among U.S. cities as a retirement destination,[56] as one of the best Midwestern cities for relocation,[57] best for rental property investing,[58] and best in a composite measure that considered local employment outlook and housing affordability.[59]

A 2013 analysis by site selection consulting firm The Boyd Company, Inc. ranked Indianapolis as the most cost competitive market for corporate headquarters facilities in the United States.[60] Also in 2013, Indianapolis appeared on Forbes' list of Best Places for Business and Careers.[61]

In 2014, a report by Battelle Memorial Institute and Biotechnology Industry Organization indicated that the Indianapolis-Carmel Metropolitan Statistical Area was the only U.S. metropolitan area to have specialized employment concentrations in each of the five bioscience sectors evaluated in the study: agricultural feedstock and chemicals; bioscience-related distribution; drugs and pharmaceuticals; medical devices and equipment; and research, testing, and medical laboratories.[62]

Municipal[63] and state[64] government agencies offer incentives to startup firms and other small businesses in Indianapolis. Four facilities designated as Indiana Certified Technology Parks are located in the city: CityWay and Downtown Indianapolis Certified Technology Park/Indiana University Emerging Technologies Center, both in the downtown area; Intech Park, in Pike Township, Marion County; and Purdue Research Park of Indianapolis - Ameriplex, in Decatur Township, Marion County.[65]

Culture

Indianapolis prides itself on its rich cultural heritage. Several initiatives have been made by the Indianapolis government in recent years to increase Indianapolis's appeal as a destination for arts and culture.

- Cultural Districts

Indianapolis has designated six official Cultural Districts. They are Broad Ripple Village, Massachusetts Avenue, Fountain Square, The Wholesale District, Canal and White River State Park, Market East[66] and Indiana Avenue. These areas have held historic and cultural importance to the city. In recent years they have been revitalized and are becoming major centers for tourism, commerce and residential living.

- Cultural Trail

Constructed between 2007 and 2013, the Indianapolis Cultural Trail is an urban bike and pedestrian path that connects the city's five downtown Cultural Districts, neighborhoods and entertainment amenities, and serves as the downtown hub for the entire central Indiana greenway system. The trail includes benches, bike racks, lighting, signage and bike rentals/drop-offs along the way and also features local art work. It was officially opened in May 2013.[67][68]

- Monument Circle

At the center of Indianapolis is Monument Circle, a traffic circle at the intersection of Meridian and Market Streets, featuring the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument. Monument Circle is depicted on the city's flag. It is in the shadow of Indiana's tallest skyscraper, the Chase Tower. Until the early 1960s, Indianapolis zoning laws stated that no building could be taller than the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. Each Christmas season, lights are strung onto the monument and lit in a ceremony known as the Circle of Lights, which attracts tens of thousands of Hoosiers to downtown Indianapolis on the day after Thanksgiving.

- War Memorial Plaza

A five-block plaza at the intersection of Meridian and Vermont surrounds a large memorial dedicated to Hoosiers who have fought in American wars. It was originally constructed to honor the Indiana soldiers who died in World War I, but construction was halted due to lack of funding during the Great Depression, and it was finished in 1951. The purpose of the memorial was later altered to encompass all American wars in which Hoosiers fought.

The monument is modeled after the Mausoleum of Maussollos. At 210 feet (64 m) tall, it is approximately 75 feet taller than the original Mausoleum. On the north end of the War Memorial Plaza is the national headquarters of the American Legion and the Indianapolis Public Library's Central Library.

- Indiana Statehouse

The Statehouse houses the Indiana General Assembly, the Governor of Indiana, state courts, and other state officials.

- Monuments

The city is second only to Washington, D.C., for the number of war monuments inside city limits.[69]

- The Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument, located at Monument Circle in the geographic center of the city.

- Indiana World War Memorial Plaza

- Medal of Honor Memorial

- USS Indianapolis Memorial

- Landmark for Peace Memorial

- Project 9/11 Indianapolis

- Other heritage and history attractions

- American Legion National Headquarters

- Crown Hill Cemetery

- James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home

- Lockerbie Square

- Cole-Noble District

- Indianapolis City Market

- Madame Walker Theatre Center

- Morris-Butler House

- Obelisk Square

- President Benjamin Harrison Home

- Scottish Rite Cathedral

Theaters and performing arts venues

Indianapolis is home to the following theaters, offering plays, Broadway productions, concerts, and other live performances.

- Beef & Boards Dinner Theatre

- Clowes Memorial Hall at Butler University

- Indiana Repertory Theatre

- Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra at Hilbert Circle Theater

- Madame Walker Theatre Center

- Murat Theater

- Old National Centre

- Phoenix Theatre (Indianapolis)

Museums and galleries

Indianapolis has a wide variety of museums and galleries which appeal to art lovers, car enthusiasts, sports fans, history buffs, and science and technology brain acts.

- Children's Museum of Indianapolis

- Indiana State Museum

- Indiana State Police Museum

- Indianapolis Art Center

- Indianapolis Museum of Art

- Indianapolis Artsgarden

- Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art

- Herron School of Art

- NCAA Hall of Champions (Hall of Fame for college athletics)

- Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame Museum

- National Art Museum of Sport

- Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum

- Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art

- James Whitcomb Riley Museum Home

- Conner Prairie (A living history museum)

- Indiana Historical Society

- Indiana Medical History Museum

- Kurt Vonnegut Memorial Library

- Dean Johnson Gallery

Other points of interest

- Heslar Naval Armory

- Humane Society of Indianapolis

- Indiana State Fairgrounds

- Indianapolis Public Library

- Irvington Historic District

- Slippery Noodle Inn

Conventions

In 2003, Indianapolis began hosting Gen Con, the largest role-playing game convention in the North America (with record attendance being over 56,000 in 2014[71]) at the Indiana Convention Center. Attendance of the event is expected to increase as the center is expanded. The convention center has also recently hosted to events such as Star Wars Celebration II and III, which brought in Star Wars fans from around the world, including George Lucas. In addition, the convention center is the current home to the Pokémon U.S. National Championships.

Indianapolis hosted Super Bowl XLVI at Lucas Oil Stadium in 2012, the first Super Bowl to be played in the city. The event attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors to the city, and was by most accounts largely successful for the city, making a proposed bid for a future Super Bowl likely.

Indianapolis hosted the National FFA Convention from 2006 to 2012[72] and will rotate with Louisville every three years starting in 2013. The FFA Convention draws approximately 55,000 attendees and has an estimated $30–$40 million direct visitor impact on the local economy. Attendees occupy 13,000 hotel rooms in 130 metro-area hotels on peak nights during the four-day convention, making it the largest convention in the history of Indianapolis.

Organizations

Indianapolis has evolved into a center for music. The city plays host to Music for All, Inergy, Indy's Official Musical Ambassadors, the Percussive Arts Society, and the American Pianists Association.[73]

As well as being the home of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, Indianapolis is also home to Bands of America (BOA), a nationwide organization of high school marching, concert, and jazz bands. Indianapolis is now also the international headquarters of Drum Corps International, a professional drum and bugle corps association.

Indianapolis has been the headquarters of the Kiwanis International organization since 1982. The organization and its youth-sponsored Kiwanis Family counterparts, Circle K International and Key Club International, administer all their international business and service initiatives from Indianapolis.

Indianapolis contains the national headquarters for twenty-six fraternities and sororities, many of which are congregated in the College Park area surrounding The Pyramids.

Festivals and events

The International Violin Competition of Indianapolis, Indy Jazz Fest, and the DCI World Championships are all held in Indianapolis.

The Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra has hosted an annual outdoor summer concert series at Conner Prairie called Marsh Symphony on the Prairie since 1982, featuring a variety of musical styles.[74]

The city has an arts community that includes many fairs celebrating a wide variety of arts and crafts. They include the Broad Ripple Art Fair, Talbot Street Art Fair, Carmel Arts Festival, Indian Market and Festival, and the Penrod Art Fair.

Every May since 1957, Indianapolis has held the 500 Festival, a month of events including a mini marathon and a festival parade, the latter being the day before the Indianapolis 500.

Indianapolis is also home to the Indiana State Fair as well as the Heartland Film Festival, the Indianapolis International Film Festival, the Indianapolis Theatre Fringe Festival, the Indianapolis Alternative Media Festival, and the Midwest Music Summit.

The Circle City Classic is one of America's top historically African-American college football games. This annual football game, held during the first weekend of October, is the showcase event of an entire weekend. The weekend is a celebration of cultural excellence and educational achievement while showcasing the spirit, energy and tradition of America's historically black colleges and universities.

One of the largest ethnic and cultural heritage festivals in Indianapolis is the Summer Celebration held by Indiana Black Expo. This ten-day national event highlights the contributions of African-Americans to U.S. society and culture and provides educational, entertainment, and networking opportunities to the over 300,000 participants from around the country.

During the month of June, the Indianapolis Italian Street Festival is held at Holy Rosary Church just south of downtown.

Indy's International Festival is held annually in November at the Indiana State Fairgrounds. Local ethnic groups, vendors and performers are featured alongside national and international performers.

Since 2006, in the months of March and October, Midwest Fashion Week[75][76] takes place, promoting both local and national designers. Started by Berny Martin of Catou,[75][76] this event has grown to become a premier event in Indianapolis.

Sports

The labels of The Amateur Sports Capital of the World and The Racing Capital of the World have both been applied to Indianapolis.[77] The headquarters of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), the main governing body for U.S. collegiate sports, is located in Indianapolis, as is the National Federation of State High School Associations. The city is home to the headquarters of three NCAA athletics conferences, the Horizon League (Division I), the Great Lakes Valley Conference (Division II), and the Heartland Collegiate Athletic Conference (Division III). The national offices for the governing bodies of several sports are located in Indianapolis, including USA Gymnastics, USA Diving, US Synchronized Swimming, and USA Track & Field.

Indianapolis has hosted numerous sporting events, including the US Open Series' Indianapolis Tennis Championships (1988–2009), the 2002 World Basketball Championships, the 2011 Big Ten Football Championship Game, Super Bowl XLVI (in 2012), and the 1987 Pan American Games. Other notable annual sporting events include the Drum Corps International World Championships, and the Music for All Bands of America Grand National Championships. Starting in 2002, Indianapolis began hosting the Big Ten Conference Men's Basketball Tournament at Bankers Life Fieldhouse, alternating years with the United Center in Chicago. From 2008 to 2012, Indianapolis was the sole city to host the tournament. Beginning in 2013, Chicago and Indianapolis began alternating again.[78]

Indianapolis is home to the OneAmerica 500 Festival Mini-Marathon, the largest mini-marathon (and eighth-largest running event) in America. 2007 was the 30th anniversary of the Mini, run in the first weekend in May every year. This event is part of the 500 Festival, its 50th year running. The race starts on Washington Street just off Monument Circle, goes to the brickyard, and ends on New York Street back downtown. The Mini has been sold out every year, with well over 35,000 runners participating.

Teams

Indianapolis is home to two major league sports teams. The Indianapolis Colts of the National Football League (NFL) have been based in Indianapolis since relocating there in 1984, and play their home games in Lucas Oil Stadium. The Indiana Pacers of the National Basketball Association (NBA) play their home games at Bankers Life Fieldhouse; they began play in 1967 in the American Basketball Association (ABA) and joined the NBA when the leagues merged in 1976.

| Team | Sport | League | Founded | Venue (capacity) | Attendance | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indianapolis Colts | Football | NFL | 1984 | Lucas Oil Stadium (62,000) | 65,950 | 2006 (XLI) |

| Indiana Pacers | Basketball | NBA | 1967 | Bankers Life Fieldhouse (18,000) | 17,501 | 1970*, 1972*, 1973* |

| Indy Eleven | Soccer | NASL (D2) | 2013 | IU Michael A. Carroll Stadium (12,100) | 10,465 | —— |

| Indianapolis Indians | Baseball | IL (AAA) | 1902 | Victory Field (12,000) | 9,433 | (7 titles)** |

| Indiana Fever | Basketball | WNBA | 2000 | Bankers Life Fieldhouse (18,000) | 7,900 | 2012 |

| Indy Fuel | Hockey | ECHL | 2014 | Indiana Farmers Coliseum (6,300) | —— | —— |

* Pacers titles were ABA only.

** Indians seven titles were in 1917, 1928, 1949, 1956, 1988, 1989, and 2000.

Auto racing

Indianapolis is a major center for automobile racing. Since 1911, the Indianapolis 500 has been the premier event in the National Championship of open wheel car racing. The series' headquarters and many of its teams are based in the city. Indianapolis is so well connected with racing that it has inspired the name "Indy car," used for both the competition and type of car used in it.[79] Indianapolis Motor Speedway hosts three major motor racing events every year: the Indianapolis 500, the Brickyard 400, and the Red Bull Indianapolis Grand Prix.

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway (IMS), located in Speedway, Indiana, is the site of the Indianapolis 500-Mile Race (also known as the Indy 500), an open–wheel automobile race held each Memorial Day weekend on a 2.5 miles (4.0 km) oval track. The Indy 500 is the largest single–day sporting event in the world, hosting more than 257,000 permanent seats (not including the infield area). The track is often referred to as the Brickyard, because it was paved with 3.2 million bricks shortly after its construction in 1909. Today the track is paved in asphalt, although a one–yard strip of bricks remains at the start/finish line.

IMS also hosts the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series' Brickyard 400. The first running of the Brickyard 400 was in 1994, and the race has traditionally been NASCAR's highest attended event.[80] Jeff Gordon has frequented victory lane five times at Indianapolis, the most of any NASCAR driver.

From 2000 to 2007, IMS hosted the Formula One United States Grand Prix (USGP). Contract negotiations between IMS and Formula One resulted in a discontinuation of the USGP at Indianapolis in 2007. The USGP was not a part of the Formula One calendar from 2008–2011, but has been held in Austin, Texas since 2012.

The Speedway hosted its first MotoGP event in 2008, with the Red Bull Indianapolis Grand Prix taking place in September. Each year the event has been held, there has been a different rider in victory circle (Valentino Rossi in 2008, Jorge Lorenzo in 2009, Dani Pedrosa in 2010, and Casey Stoner in 2011).

Indianapolis is also home to Lucas Oil Raceway at Indianapolis. Though not as well known as Indianapolis Motor Speedway, Lucas Oil Raceway is home to the NHRA Mac Tool U.S. Nationals, the biggest, oldest, richest, and most prestigious drag race in the world. The event is held every Labor Day weekend.

Recreation

Parks

Indianapolis has an extensive municipal park system with nearly 200 parks occupying over 10,000 acres (40 km2). The flagship Eagle Creek Park is the largest municipal park in the city, and ranks among the largest urban parks in the United States.[81]

Other major Indianapolis Regional parks include:

- Garfield Park (Established in 1881, it is the oldest city park in Indianapolis and contains a conservatory and sunken gardens. Located on the Near South Side)

- Riverside Park (Near West Side)

- Sahm Park (Northeast side)

- Southeastway Park (Franklin Township, Marion County)

- Southwestway Park (Decatur Township, Marion County)

- White River State Park (Just West of downtown. Has cultural, educational and recreational attractions as well as trails and waterways.)

Additionally, Indianapolis has an urban forestry program that is recognized by the National Arbor Day Foundation's Tree City USA standards.

Indianapolis Zoo

Opened in 1988, the Indianapolis Zoo is the largest zoo in the state, and is located just west of downtown in White River State Park. It has 360 species of animals, and is known for its dolphin exhibit.

Law and government

Indianapolis has a consolidated city-county government known as Unigov. Under this system, many functions of the city and county governments are consolidated, though some remain separate. The city has a mayor-council form of government.

The executive branch is headed by an elected mayor, who serves as the chief executive of both the city and Marion County. The current Mayor of Indianapolis is Republican Greg Ballard. The mayor appoints deputy mayors, city department heads and members of various boards and commissions.

The legislative body for the city and county is the City-County Council. It is made up of 29 members, 25 of whom represent districts, with the remaining four elected at large. Following the 2011 elections, Democrats hold a 16–13 majority over Republicans. The council passes ordinances for the city and county and also makes appointments to certain boards and commissions.

With the exception of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, all of the courts of law in Indianapolis are part of the Indiana state court system. The Marion Superior Court is the court of general jurisdiction. The 35 judges on the court hear all criminal, juvenile, probate, and traffic violation cases, as well as most civil cases. The Marion Circuit Court hears certain types of civil cases. Small claims cases are heard by Small Claims Courts in each of Marion County's nine townships. The Appeals Courts and the Indiana Supreme Court meet in the Indiana Statehouse.

Fire protection

The Indianapolis Fire Department provides fire protection services for six townships in Marion County (Washington, Lawrence, Center, Warren, Perry, and Franklin), plus those portions of the other three townships that were part of Indianapolis prior to the establishment of Unigov. The individual fire departments of Decatur, Pike, and Wayne townships, the town of Speedway, and the cities of Beech Grove and Lawrence, provide such services for their respective jurisdictions.

Emergency medical services

Emergency medical services (EMS) for six townships in Indianapolis (Washington, Lawrence, Center, Warren, Perry and Franklin) and the Town of Speedway are provided by Indianapolis Emergency medical services. The fire departments of Decatur, Pike and Wayne Townships, as well as the cities of Beech Grove and Lawrence, provide EMS services to their respective jurisdictions.

Law enforcement

Indianapolis and Marion County historically maintained separate police agencies: the Indianapolis Police Department and Marion County Sheriff's Department. On January 1, 2007, a new agency, the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department, was formed by merging the two departments. IMPD is a separate agency, as the Sheriff's Department maintains jail and court functions. IMPD has jurisdiction over those portions of Marion County not explicitly covered by the police of an excluded city or by a legacy pre-Unigov force. As of February 29, 2008, the IMPD is headed by a Public Safety Director appointed by the Mayor of Indianapolis; the Public Safety Director appoints the Police Chief. The IMPD was formerly under the leadership of the Sheriff of Marion County, Frank J. Anderson prior to his retirement in January, 2011. The Sheriff remains in charge of the County Jail and security for the City-County Building, service of warrants, and certain other functions. The Sheriff must be consulted, but does not have final say, on the appointment of the Public Safety Director and the Police Chief.[82]

Crime

In the late 1990s, violent crimes in inner city neighborhoods located within the old city limits (pre-consolidation) peaked. The former Indianapolis Police District (IPD), which serves about 37% of the county's total population and has a geographic area covering mostly the old pre-consolidation city limits, recorded 130 homicides in 1998 to average approximately 40.3 homicides per 100,000 people. This is over 6 times the 1998 national homicide average of 6.3 per 100,000 people. [citation needed] Meanwhile, the former Marion County Sheriff's Department district serving the remaining 63% of the county's population, which includes the majority of the residents in the Consolidated City, recorded only 32 homicides in 1998, averaging about 5.9 murders per 100,000 people, slightly less than the 1998 national homicide average. Homicides in the IPD dropped dramatically in 1999 and have remained lower through 2005. In 2005, the IPD recorded 88 homicides to average 27.3 homicides per 100,000 people; nonetheless, the murder rate in the IPD is still almost 5 times the 2005 national average. In 2007, city leaders such as Sheriff Frank J. Anderson and former Mayor Bart Peterson held rallies in neighborhoods in effort to stop the violence in the city.

The immediate downtown area of the city around most main attractions, venues, and museums remain relatively safe. IMPD uses horseback officers and bicycle officers to patrol the downtown area or the city. Certain areas of Indianapolis remain a challenge for law enforcement officials. Indianapolis was ranked as the 33rd most dangerous city in the United States in the 2008–2009 edition of CQ Press's City Crime Rankings and the 22nd most dangerous city according to Yahoo! Finance in 2012.[83][84] Yahoo! Finance also reported that the city averaged 52.2 forcible rapes per 100,000 people. The national average stands at 26.8 forcible rapes per 100,000 people.[84]

Politics

Until the late 1990s, Indianapolis was considered to be one of the most conservative metropolitan areas in the country but this trend has reversed recently. Republicans had held the majority in the City-County Council for 36 years, and the city had a Republican mayor for 32 years from 1967 to 1999. This was in part because the creation of Unigov added several then-heavily Republican areas of Marion County to the Indianapolis city limits. More recently, Republicans have generally been stronger in the southern and western parts (Decatur, Franklin, Perry, and Wayne, townships) of the county while Democrats have been stronger in the central and northern parts (Center, Pike, and Washington townships). Republican and Democratic prevalence is split in Warren and Lawrence townships.[85] The Indianapolis suburbs, on the other hand, remain some of the most reliably Republican areas in Indiana and the nation.

In the 1999 municipal election, Democrat Bart Peterson defeated Indiana Secretary of State Sue Anne Gilroy by 52% to 41%. Four years later, Peterson was re-elected with 63% of the vote over Marion County Treasurer Greg Jordan. Republicans narrowly lost control of the City-County Council that year. In 2004, Democrats won the Marion County offices of treasurer, surveyor and coroner for the first time since the 1970s. The county GOP lost further ground during the 2006 elections with Democrats winning the offices of county clerk, assessor, recorder and auditor. Only one GOP countywide office remained: Prosecutor Carl Brizzi, who defeated Democratic challenger Melina Kennedy with 51% of the vote in his bid for a second term, despite outspending her two-to-one. At the township level, Democrats picked up the trustee offices in Washington, Lawrence, Warren and Wayne townships, while holding on to Pike and Center townships.

In the 2007 municipal election, fueled by voter angst against increases in property and income taxes as well as a rise in crime, Republican challenger Greg Ballard narrowly defeated Peterson 51% to 47%—the first time an incumbent Indianapolis mayor was removed from office since 1967. Discontent among these issues also returned control of the City-County Council to the GOP with a 16–13 majority.[86] Ballard was re-elected mayor in 2011. Control of the city-county council reverted to Democrats 16-13 over Republicans, marking only the second time in the Unigov era of split-party control of county government between the council and mayor.

In the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama easily won in Indianapolis by earning 64% of all Marion County votes while 35% of the votes went to John McCain for a victory of about 107,000 votes.[87]

As 2010 came to an end, despite a strong performance by the GOP statewide, Democrats swept all county offices once again, including reclaiming the office of county prosecutor for the first time since 1990.

In the 2012 presidential election Obama again performed very strongly, defeating Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney 60% to 38% for an 80,000 vote victory.

In 2013, city-county councilor Jose Evans changed party affiliation from Democrat to Republican, giving the Democrats a 15-14 majority over Republicans.[citation needed][undue weight? – discuss]

Most of Indianapolis is within the 7th Congressional District of Indiana, represented by Democrat André Carson. He is the grandson of the district's previous representative, Julia Carson who held the seat from 1997 until her death on December 15, 2007.[88] The northern portions of the city are in the 5th District, represented by Republican Susan Brooks.[89]

Education

Higher education

Indianapolis is the home of Butler University, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana, Indiana Tech (4 satellite campuses), Lincoln College of Technology, Marian University, Martin University, Oakland City University–Indianapolis, The Art Institute of Indianapolis, Vincennes University Aviation Technology Center, the University of Indianapolis, the University of Phoenix, and WGU Indiana.

Butler University was originally founded in 1855 as North Western Christian University. The school purchased land in the Irvington area in 1875. The school moved again in 1928 to its current location at the edge of the Butler-Tarkington neighborhood. The school removed itself officially from religious affiliation, giving up the theological school to Christian Theological Seminary. A private institution, Butler's current student enrollment is approximately 4,400. Butler has a storied sports heritage in regards to basketball and volleyball. Butler is the site where both the film Hoosiers and the events that inspired it were filmed, the so-called Milan Miracle. Butler's basketball stadium, Hinkle Fieldhouse, was the largest basketball facility when built and also historically hosted the first bout between the U.S. and Soviet Union in basketball. Butler University made its own impact felt with a championship appearance in its home city of Indianapolis in the NCAA championship game in 2010, and a repeat appearance in the NCAA Championship game in 2011. Butler also has hosted to date the largest attended volleyball match at 14,000 spectators.

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis was originally an urban conglomeration of branch campuses of the two major state universities: Indiana University in Bloomington and Purdue University in West Lafayette, created by the state legislature. In 1969 a merged campus was created at the site of the Indiana University School of Medicine. IUPUI's student body is currently just above 30,000, making it the third-largest campus for higher learning in Indiana after the main campuses of IU and Purdue. The Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law is located on the IUPUI campus; the school's distinctive Inlow Hall is located on the southeast corner of the campus. This campus is also home to Herron School of Art and Design, which was established privately in 1902. A new building was built in 2005 under both private donation and state contribution enabling the school to move from its original location. IUPUI has a division one basketball program and has made tournament appearances in the Summit League alongside Indianapolis's other division one school, Butler University. IUPUI has the only Android Studies Department in the United States.

Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana, a state funded public school, was founded as Indiana Vocational Technical College in 1963. In 2008, Ivy Tech became "the state's largest public-college system, surpassing Indiana University in enrollment."[90] With 30 campuses across Indiana, Ivy Tech has a total enrollment of over 174,000 as of the 2010-2011 school year.[91]

Marian University was founded in 1936 when St. Francis Normal and Immaculate Conception Junior College merged. The college moved to Indianapolis in 1937. Marian is currently a private Catholic school and has an enrollment of approximately 2,400 students.

The University of Indianapolis is a private school affiliated with the United Methodist Church. Founded in 1902 as Indiana Central University, the school's current enrollment is approximately 5,000 students. The University of Indianapolis prides itself on its teaching and nursing programs, as well as its opportunities to study abroad. UIndy has satellite campuses in Cyprus, Jerusalem, and at the base of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece.

Primary and secondary education

Indianapolis has eleven unified public school districts (eight township educational authorities and three legacy districts from before the unification of city and county government), each of which providing primary, secondary, and adult education services within its boundaries. The boundaries of these districts do not exactly correspond to township (or traditional) boundaries, but rather cover the areas of their townships that were outside the pre-Unigov city limits. Indianapolis Public Schools, which serves what was the city of Indianapolis prior to the Unigov merger, is still the largest school corporation in Indiana today.

Private schools run by the Archdiocese of Indianapolis are Bishop Chatard, Roncalli, Cardinal Ritter, and Scecina. Other private schools include Brebeuf Jesuit, Park Tudor, Cathedral and Heritage Christian.

Libraries

Public library services are provided to the citizens of Indianapolis and Marion County by the Indianapolis Public Library. The educational and cultural institution, founded in 1873, now consists of a main library, Central Library, located in downtown Indianapolis, and 22 branch locations spread throughout the city. Serving over 5.43 million visitors in 2006, its mission is to provide "materials and programs in support of the lifelong learning, recreational and economic interests of all citizens of Marion County." The renovated Central Library building opened on December 9, 2007, ending a controversial multi-year rebuilding plan.[92]

Media

Broadcast television network affiliates include WTTV (CBS),[93] WRTV (ABC),[94] WISH-TV (CW),[95] WTHR-TV (NBC),[96] WXIN-TV (Fox),[97] WFYI-TV (PBS),[98] WNDY-TV (MyNetworkTV),[99] and WDNI-CD (Telemundo).[100] In 2009, Indianapolis was the 25th largest media market in the United States, with over 1.1 million homes.

The Indianapolis Star serves as the city's primary morning daily newspaper, with a weekday circulation of 255,303 and Sunday circulation of 324,349. Other publications include The Indianapolis Recorder, a weekly newspaper serving the local African-American community, Indianapolis Monthly, Indianapolis Women's Magazine, Indy Men's Magazine, and NUVO. Indianapolis is also corporate headquarters of media conglomerate Emmis Communications. The company owns radio stations and magazines in the United States, Hungary, Slovakia, and Bulgaria.

Transportation

Airports

Indianapolis International Airport is the largest airport in Indiana, serving about 7.5 million passengers and transporting 985,000 tons of cargo annually.[101] The airport is home to the second-largest FedEx operation in the world and the USPS Eagle Network Hub. The entire airport is a global free trade zone called INZONE with eighteen designated subzones.

Thirty years in planning, a new midfield terminal complex was completed in 2008. It officially opened for arriving flights on November 11, 2008 and departures on November 12, 2008. The $1.1 billion project represents the largest development initiative in the city's history. The Colonel H. Weir Cook Terminal covers 1,200,000 square feet (110,000 m2), includes 40 gates, a 145,000 sq ft (13,500 m2) baggage processing area, a 73,000 sq ft (6,800 m2) baggage claim area, a large pre-security gathering, a concession space with a 60-foot (18 m) skylight, numerous local and national restaurants and retailers, and local Indianapolis artwork. Indianapolis International Airport's new terminal structure was the first one built in the U.S. since the 9/11 attacks.

Ten major U.S. and international airlines serve the airport.[102]

Highways

Several interstates serve the Indianapolis area. Interstate 65 runs northwest to Gary, where other roads eventually take drivers to Chicago, and southward to Louisville, Kentucky. Interstate 69 runs northeast to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and currently terminates in the city at I-465, but will eventually be routed around the city on 465 to the new extension of Interstate 69 towards Evansville. Interstate 70 follows the old National Road, running east to Columbus, Ohio and southwest to St. Louis, Missouri. Interstate 74 goes northwest towards Danville, Illinois, and southeast towards Cincinnati, Ohio. Finally, Interstate 465 circles Marion County, and joins the aforementioned highways together. In 2002, the interstate segment connecting Interstate 465 to Interstate 65 on the northwest side of the city was redesignated Interstate 865 to reduce confusion. The Indianapolis area also has two other expressways: Sam Jones Expressway (formerly Airport Expressway), and Shadeland Avenue Expressway.

To comply with an Indiana state law limiting the number of miles of state highways,[citation needed] all US and Indiana State numbered routes were rerouted along I-465 instead of going through the center of the city. At one point (between Exits 47 and 49) on the southeast side of the city, I-465, U.S. 31, U.S. 36, U.S. 52, U.S. 421, Indiana 37, and Indiana 67 use the same right-of-way. Between Exits 49 and 2 (along the south end of the city), I-74, I-465, U.S. 31, U.S. 36, U.S. 52, Indiana 37 and Indiana 67 operate on the same right-of-way.

Intercity

Amtrak, the national passenger rail system, provides two service lines to Indianapolis via Indianapolis Union Station. The Cardinal (New York)—Washington, D.C.—Cincinnati—Indianapolis—Chicago) runs three times a week, while the Hoosier State (to Chicago) runs on days the Cardinal does not operate.

Greyhound Lines operates a bus terminal at Indianapolis Union Station, and Megabus has a stop adjacent to the Indianapolis City-County Building.

Mass transit

The Indianapolis Public Transportation Corporation (known locally as IndyGo) provides public transportation for the city. IndyGo was established in 1975 after the city of Indianapolis took control of the city's transit system. Prior to 1997, IndyGo was called Metro. Central Indiana Commuter Services (CICS), funded by IndyGo to reduce pollution, serves Indianapolis and surrounding counties.

Efforts to expand mass transit in Central Indiana have been initiated through an organization called IndyConnect.[103] Starting in 2010, private industry leaders throughout the region proposed a $10 billion multi-modal transportation plan that includes expanded roadways, express bus routes, light rail, and commuter rail services. If public and legislative approval is granted, construction could begin as soon as 2015. In addition, a private company known as Downtown Indianapolis Streetcar Corp., has put together a team to study the possibilities of creating a streetcar for the downtown Indianapolis area.[104]

People mover

Since 2003, Indiana University Health has operated a 1.4-mile (2.3 km) long, 4 ft (1,219 mm) narrow gauge[105] people mover. The system connects the medical centers of Indiana University Hospital, James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children, and Methodist Hospital of Indianapolis with related facilities on the IUPUI campus. Though open to the public, the system is privately run. It is currently the only example of light or commuter rail in Indianapolis and is also notable for being the only private transportation system in the U.S. constructed above public streets.[106][107]

Notable people

Sister cities

Indianapolis has eight sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:[108]

Taipei, Taiwan (1978)

Taipei, Taiwan (1978) Cologne, Germany (1988)

Cologne, Germany (1988) Monza, Italy (1993)

Monza, Italy (1993) Piran, Slovenia (2001)

Piran, Slovenia (2001) Hangzhou, People's Republic of China (2009)

Hangzhou, People's Republic of China (2009) Campinas, Brazil (2009)

Campinas, Brazil (2009) Northamptonshire, United Kingdom (2009)

Northamptonshire, United Kingdom (2009) Hyderabad, India (2010)

Hyderabad, India (2010)

See also

Notes

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Indianapolis kept at downtown from February 1871 to December 1942, and at Indianapolis Int'l since January 1943. For more information, see Threadex

References

- ^ a b c d e "Indianapolis (city (balance)), Indiana". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Indiana's 2010 Census Population Totals". Retrieved February 11, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Indiana's 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 18, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "NUVO". NUVO. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Indianapolis named one of Livability's 'Top 10 Downtowns'". Fox 59. Retrieved July 8, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "U.S. Census Figures". United States Census. 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Annual Awards | Sister Cities International (SCI)". Sister-cities.org. July 13, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ Bodenhamer, David J.; Robert Graham Barrows; David Gordon Vanderstel (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31222-1. p. 1042

- ^ Caldwell, Howard; Jones, Darryl (1990). Goodall, Kenneth (ed.). Indianapolis. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-32998-1. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

- ^ Morning Edition. "Robert Kennedy: Delivering News of King's Death". NPR. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ "Indiana Convention Center Expansion Revealed". WISH-TV. June 25, 2007. Retrieved January 16, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Indiana InDepth Profile: Largest Cities and Towns in Indiana (35,000+)". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University, Kelley School of Business. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ William A. Browne Jr. (Summer 2013). "The Ralston Plan: Naming the Streets of Indianapolis". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 25 (3). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 8 and 9.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Browne, p. 11 and 16.

- ^ Michigan did not enter the Union until 1837. See Browne, p. 9 and 17.

- ^ Brown, p. 9 and 10.

- ^ Browne, p. 17

- ^ "Statistics - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)". The Indianapolis Public Library. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Guide for Moving to Indianapolis, Indiana". MoveInAndOut.com. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

NOAAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Indianapolis Climatological Information". National Weather Service, Weather Forecast Office. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Average Weather for Indianapolis International Airport, IN — Temperature and Precipitation". The Weather Channel. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Indianapolis, TN". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for INDIANAPOLIS/INT'L ARPT IN 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Indianapolis, Indiana - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Community Facts". Factfinder2.census.gov. October 5, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "2011 estimate". Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "Indianapolis (city (balance)), Indiana". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ a b From 15% sample

- ^ a b c "Indiana InDepth Profile: Largest Cities and Towns in Indiana (35,000+)". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University, Kelley School of Business. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data for Indianapolis city (balance), Indiana". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ In 2011 the population of Indianapolis was estimated to be 839,489. See "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Indiana's 2010 Census Population Totals". Retrieved February 11, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ "Indianapolis-Carmel, IN Metro Area". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University, Kelley School of Business. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ The U.S. Census for 2010 reports the female population for Indianapolis as 424,099 (323,845 were age 18 and over) and the male population as 396,346 (291,745 were age 18 and over). See "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data for Indianapolis city (balance), Indiana". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ a b "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2007-2011 American Community Survey". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ In the largest cities of the Midwest, Indianapolis had 24.4 percent of its residents living on black-white integrated city blocks. St. Louis, Missouri, had the highest level of black-white integration, with 27 percent, and Chicago had the lowest at 6 percent. See Lois M. Quinn and John Pawasarat (December 2002, revised January 2003). "Racial Integration in Urban America: A Block Level Analysis of African American and White Housing Patterns" (PDF). Employment and Training Institute, School of Continuing Education, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "http://www.jsonline.com/news/metro/jan03/110491.asp" (PDF). Retrieved July 1, 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Racial Integration in 100 Largest Metro Areas". .uwm.edu. August 8, 2002. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ a b "The Indianapolis Metro Area" (PDF). Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Us." Republic Airways Holdings. Retrieved on May 19, 2009.

- ^ "Logistics > Targeted Clusters". Develop Indy. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- ^ Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza, 1950), p.102.

- ^ Clymer, p.36.

- ^ Clymer, pp. 128–9.

- ^ Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine ATA Airlines. February 3, 2007. Retrieved on May 19, 2009.

- ^ "Best Cities For Jobs In 2008". Forbes. January 10, 2008.

- ^ Foreclosed homes lower neighborhood values – 13 WTHR. Wthr.com. Retrieved on December 24, 2010.

- ^ "Housing Affordability Record-High Level for Third Consecutive Quarter". NAHB. November 19, 2009. Retrieved July 1, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Top 10 cities for new grads. CNN.com (2009-05-13). Retrieved on December 24, 2010.

- ^ Best Cities to Move to in America – Yahoo! Real Estate[dead link]. Realestate.yahoo.com. Retrieved on 2010-12-24,

- ^ "Blog Archive » 2010 GDP Data Shows Nascent Recovery in Many American Metros". The Urbanophile. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ William P. Barrett (March 23, 2011). "The Best Retirement Places – Forbes". Forbes. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ Newgeography.com (March 18, 2010). "Midwest Success Stories". Newgeography.com. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ Van, Rich. "Indy tops magazine polls for real estate investing - 13 WTHR Indianapolis". Wthr.com. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Linda McMaken. "5 Places With Good Jobs And Cheap Housing". Finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ Ron Startner. "The Trust Belt". Conway Data. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ "Best Places For Business and Careers - Forbes". Forbes. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Battelle/BIO State Bioscience Jobs, Investments and Innovation 2014" (PDF). Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ City of Indianapolis. "Development Guide for Small Business" (PDF). Develop Indy. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ Indiana Economic Development Corporation. "IEDC Programs and Initiatives". State of Indiana. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ Indiana Economic Development Corporation. "List of Indiana Certified Technology Parks" (PDF). State of Indiana. Retrieved December 26, 2014.

- ^ smoker, joe. "Welcome to 'Market East'". urbanindy.com. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ Foxio (June 16, 2013). "Indianapolis Cultural Trail". Indyculturaltrail.org. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "Project for Public Spaces". Pps.org. May 10, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ "Marine training in Indy stirs concerns". Indianapolis Star. June 3, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "The Association of Children's Museums website". Childrensmuseums.org. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Indianapolis: The Center for the Music Arts?, Halftime Magazine. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ a b Shoger, Scott (March 7, 2012). "A Midwest Fashion Week primer". NUVO. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ a b "Midwest Fashion Week About Us". Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ "About Indianapolis, Sports and Recreation". Greater Indianapolis Chamber of Commerce. June 11, 2008. Retrieved June 11, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ InsideIndianaBusiness.com Report. "Big Ten Deal Could Mean Big Bucks – Newsroom – Inside Indiana Business with Gerry Dick". Insideindianabusiness.com. Retrieved August 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Indy car". Oxford English Dictionary. November 2010. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ "NASCAR records at the Brickyard 400 - NASCAR - Yahoo! Sports". Sports.yahoo.com. July 19, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Parks, City of Indianapolis

- ^ "Council vote gives Ballard IMPD control". Indianapolis Star. April 3, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Kathleen O'Leary Morgan and Scott Morgan, editors (2008). City Crime Rankings 2008–2009. CQ Press. ISBN 978-0-87289-932-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) Retrieved on January 2, 2009. - ^ a b Abby Rogers (2012). The 25 Most Dangerous Cities in America. Yahoo! Finance. ISBN 978-0-87289-932-2. Retrieved on November 3, 2012.

- ^ "Voter turnout a key factor in Carson win". Indianapolis Star. March 15, 2008. Retrieved March 15, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "Internet Archive Wayback Machine". Web.archive.org. November 9, 2007. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Indiana General Election November 4, 2008, by County". Indiana Secretary of State. November 4, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ Rep. Julia Carson dies at age 69, WISHTV, December 16, 2007

- ^ "The National Atlas". nationalatlas.gov. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Soderlund, Kelly (December 12, 2011). "Ivy Tech grows to biggest state college". The Journal Gazette. Fort Wayne, Indiana. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Ivy Tech Community College Institutional Progress Report 2010-11" (PDF). http://www.in.gov/che. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Storybook Ending?, Indianapolis Star. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ^ "CBS4Indy". CBS4Indy.com. Retrieved January 4, 2015.

- ^ "Indianapolis News, Indianapolis, Indiana News, Weather, and Sports — WRTV Indianapolis' Channel 6". Theindychannel.com. January 7, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Indianapolis, Indiana News Weather & Traffic". WISHTV.com. Retrieved July 1, 2010.