System

A system is a set of interacting or interdependent components forming an integrated whole.[1]

Every system is delineated by its spatial and temporal boundaries, surrounded and influenced by its environment, described by its structure and purpose and expressed in its functioning.

Fields that study the general properties of systems include systems science, systems theory, systems modeling, systems engineering, cybernetics, dynamical systems, thermodynamics, complex systems, system analysis and design and systems architecture. They investigate the abstract properties of systems' matter and organization, looking for concepts and principles that are independent of domain, substance, type, or temporal scale.[citation needed]

Some systems share common characteristics, including:[citation needed]

- A system has structure, it contains parts (or components) that are directly or indirectly related to each other;

- A system has behavior, it exhibits processes that fulfill its function or purpose;

- A system has interconnectivity: the parts and processes are connected by structural and/or behavioral relationships;

- A system's structure and behavior may be decomposed via subsystems and sub-processes to elementary parts and process steps;

- A system has behavior that, in relativity to its surroundings, may be categorized as both fast and strong.

The term system may also refer to a set of rules that governs structure and/or behavior. Alternatively, and usually in the context of complex social systems, the term institution is used to describe the set of rules that govern structure and/or behavior.

Etymology

The term is from the Latin word systēma, in turn from Greek σύστημα systēma, "whole compounded of several parts or members, system", literary "composition"[2]

History

"System" means "something to look at". You must have a very high visual gradient to have systematization. In philosophy, before Descartes, there was no "system". Plato had no "system". Aristotle had no "system".[3]

In the 19th century the first to develop the concept of a "system" in the natural sciences was the French physicist Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot who studied thermodynamics. In 1824 he studied the system which he called the working substance, i.e. typically a body of water vapor, in steam engines, in regards to the system's ability to do work when heat is applied to it. The working substance could be put in contact with either a boiler, a cold reservoir (a stream of cold water), or a piston (to which the working body could do work by pushing on it). In 1850, the German physicist Rudolf Clausius generalized this picture to include the concept of the surroundings and began to use the term "working body" when referring to the system.

One of the pioneers of the general systems theory was the biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy. In 1945 he introduced models, principles, and laws that apply to generalized systems or their subclasses, irrespective of their particular kind, the nature of their component elements, and the relation or 'forces' between them.[4]

Significant development to the concept of a system was done by Norbert Wiener and Ross Ashby who pioneered the use of mathematics to study systems.[5][6]

In the 1980s the term complex adaptive system was coined at the interdisciplinary Santa Fe Institute by John H. Holland, Murray Gell-Mann and others.

System concepts

- Environment and boundaries

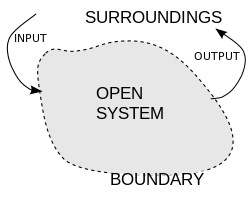

- Systems theory views the world as a complex system of interconnected parts. We scope a system by defining its boundary; this means choosing which entities are inside the system and which are outside – part of the environment. We then make simplified representations (models) of the system in order to understand it and to predict or impact its future behavior. These models may define the structure and/or the behavior of the system.

- Natural and human-made systems

- There are natural and human-made (designed) systems. Natural systems may not have an apparent objective but their outputs can be interpreted as purposes. Human-made systems are made with purposes that are achieved by the delivery of outputs. Their parts must be related; they must be “designed to work as a coherent entity” – else they would be two or more distinct systems.

- Theoretical framework

- An open system exchanges matter and energy with its surroundings. Most systems are open systems; like a car, coffeemaker, or computer. A closed system exchanges energy, but not matter, with its environment; like Earth or the project Biosphere2 or 3. An isolated system exchanges neither matter nor energy with its environment. A theoretical example of such system is the Universe.

- Process and transformation process

- An open system can also be viewed as a bounded transformation process, that is, a black box that is a process or collection of processes that transforms inputs into outputs. Inputs are consumed; outputs are produced. The concept of input and output here is very broad. E.g., an output of a passenger ship is the movement of people from departure to destination.

- Subsystem

- A subsystem is a set of elements, which is a system itself, and a component of a larger system.

- System model

- A system comprises multiple views. For the man-made systems it may be such views as concept, analysis, design, implementation, deployment, structure, behavior, input data, and output data views. A system model is required to describe and represent all these multiple views.

- Systems architecture

- A systems architecture, using one single integrated model for the description of multiple views such as concept, analysis, design, implementation, deployment, structure, behavior, input data, and output data views, is a kind of system model.

Elements of a system: an example

Following are considered as the elements of a system in terms of Information systems: –

- Input

- Output

- Processor

- Control

- Feedback

- Boundary and interface

- Environment

1. INPUT: Input involves capturing and assembling elements that enter the system to be processed. The inputs are said to be fed to the systems in order to get the output. For example, input of a 'computer system' is input unit consisting of various input devices like keyboard,mouse,joystick etc.

2. OUTPUT: Those elements that exists in the system due to the processing of the inputs is known as output. A major objective of a system is to produce output that has value to its user. The output of the system maybe in the form of cash,information,knowledge,reports,documents etc.the system is defined as output is required from it. It is the anticipatory recognition of output that helps in defining the input of the system. For example, output of a 'computer system' is output unit consisting of various output devices like screen and printer etc.

3. PROCESSOR(S): The processor is the element of a system that involves the actual transformation of input into output. It is the operational component of a system. For example, processor of a 'computer system' is central processing unit that further consists of arithmetic and logic unit(ALU), control unit and memory unit etc.

4. CONTROL: The control element guides the system. It is the decision-making sub-system that controls the pattern of activities governing input,processing and output. It also keeps the system within the boundary set. For example,control in a 'computer system' is maintained by the control unit that controls and coordinates various units by means of passing different signals through wires.

5. FEEDBACK: Control in a dynamic system is achieved by feedback. Feedback measures output against a standard input in some form of cybernetic procedure that includes communication and control. The feedback may generally be of three types viz.,positive,negative and informational. The positive feedback motivates the system. The negative indicates need of an action. The feedback is a reactive form of control. Outputs from the process of the system are fed back to the control mechanism. The control mechanism then adjusts the control signals to the process on the basis of the data it receives. Feedforward is a protective form of control. For example, in a 'computer system' when logical decisions are taken,the logic unit concludes by comparing the calculated results and the required results.

6. BOUNDARY AND INTERFACE: A system should be defined by its boundaries-the limits that identify its components,processes and interrelationships when it interfaces with another system. For example,in a 'computer system' there is boundary for number of bits, the memory size etc.that is responsible for different levels of accuracy on different machines(like 16-bit,32-bit etc.). The interface in a 'computer system'may be CUI (Character User Interface) or GUI (Graphical User Interface).

7. ENVIRONMENT: The environment is the 'supersystem' within which an organisation operates.It excludes input,processes and outputs. It is the source of external elements that impinge on the system. For example,if the results calculated/the output generated by the 'computer system' are to be used for decision-making purposes in the factory,in a business concern,in an organisation,in a school,in a college or in a government office then the system is same but its environment is different.

Types of systems

Systems are classified in different ways:

- Physical or abstract systems.

- Open or closed systems.

- 'Man-made' information systems.

- Formal information systems.

- Informal information systems.

- Computer-based information systems.

- Real-time system.

Physical systems are tangible entities that may be static or dynamic in operation.

An open system has many interfaces with its environment. i.e. system that interacts freely with its environment, taking input and returning output. It permits interaction across its boundary; it receives inputs from and delivers outputs to the outside. A closed system does not interact with the environment; changes in the environment and adaptability are not issues for closed system.

Analysis of systems

Evidently, there are many types of systems that can be analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, with an analysis of urban systems dynamics, [A.W. Steiss][7] defines five intersecting systems, including the physical subsystem and behavioral system. For sociological models influenced by systems theory, where Kenneth D. Bailey[8] defines systems in terms of conceptual, concrete and abstract systems; either isolated, closed, or open, Walter F. Buckley[9] defines social systems in sociology in terms of mechanical, organic, and process models. Bela H. Banathy[10] cautions that with any inquiry into a system that understanding the type of system is crucial and defines Natural and Designed systems.

Systems that are purposed by man inherently have a major flaw they must have a starting assumption(s) in which this starting assumption(s) is used to build further knowledge upon. This starting assumption(s) is not inherently bad, but it is used as the foundation of the system and as it is assumed to be true, and not definitively so then the system is not as structurally sound as perceived to be. For example in Geometry (a subsystem of Math) this is highly evident when one goes through the process of taking theorems and extrapolates proofs from those set theorems.

In offering these more global definitions, the author maintains that it is important not to confuse one for the other. The theorist explains that natural systems include sub-atomic systems, living systems, the solar system, the galactic system and the Universe. Designed systems are our creations, our physical structures, hybrid systems which include natural and designed systems, and our conceptual knowledge. The human element of organization and activities are emphasized with their relevant abstract systems and representations. A key consideration in making distinctions among various types of systems is to determine how much freedom the system has to select purpose, goals, methods, tools, etc. and how widely is the freedom to select itself distributed (or concentrated) in the system.

George J. Klir[11] maintains that no "classification is complete and perfect for all purposes," and defines systems in terms of abstract, real, and conceptual physical systems, bounded and unbounded systems, discrete to continuous, pulse to hybrid systems, etc. The interaction between systems and their environments are categorized in terms of relatively closed, and open systems. It seems most unlikely that an absolutely closed system can exist or, if it did, that it could be known by us. Important distinctions have also been made between hard and soft systems.[12] Hard systems are technical in nature and amenable to methods such as systems engineering, operations research and quantitative systems analysis. Soft systems involve people and organisations and are commonly associated with concepts developed by Peter Checkland and Brian Wilson through Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) involving methods such as action research and emphasizing participatory designs. Where hard systems might be identified as more "scientific," the distinction between them is actually often hard to define.

Cultural system

A cultural system may be defined as the interaction of different elements of culture. While a cultural system is quite different from a social system, sometimes both systems together are referred to as the sociocultural system. A major concern in the social sciences is the problem of order.

Economic system

An economic system is a mechanism (social institution) which deals with the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services in a particular society. The economic system is composed of people, institutions and their relationships to resources, such as the convention of property. It addresses the problems of economics, like the allocation and scarcity of resources.

Application of the system concept

Systems modeling is generally a basic principle in engineering and in social sciences. The system is the representation of the entities under concern. Hence inclusion to or exclusion from system context is dependent of the intention of the modeler.

No model of a system will include all features of the real system of concern, and no model of a system must include all entities belonging to a real system of concern.

Systems in information and computer science

In computer science and information science, system is a software system which has components as its structure and observable inter-process communications as its behavior. Again, an example will illustrate: There are systems of counting, as with Roman numerals, and various systems for filing papers, or catalogues, and various library systems, of which the Dewey Decimal System is an example. This still fits with the definition of components which are connected together (in this case in order to facilitate the flow of information).

System can also be used referring to a framework, be it software or hardware, designed to allow software programs to run, see platform.

Systems in engineering and physics

In engineering and physics, a physical system is the portion of the universe that is being studied (of which a thermodynamic system is one major example). Engineering also has the concept of a system that refers to all of the parts and interactions between parts of a complex project. Systems engineering refers to the branch of engineering that studies how this type of system should be planned, designed, implemented, built, and maintained.

Systems in social and cognitive sciences and management research

Social and cognitive sciences recognize systems in human person models and in human societies. They include human brain functions and human mental processes as well as normative ethics systems and social/cultural behavioral patterns.

In management science, operations research and organizational development (OD), human organizations are viewed as systems (conceptual systems) of interacting components such as subsystems or system aggregates, which are carriers of numerous complex business processes (organizational behaviors) and organizational structures. Organizational development theorist Peter Senge developed the notion of organizations as systems in his book The Fifth Discipline.

Systems thinking is a style of thinking/reasoning and problem solving. It starts from the recognition of system properties in a given problem. It can be a leadership competency. Some people can think globally while acting locally. Such people consider the potential consequences of their decisions on other parts of larger systems. This is also a basis of systemic coaching in psychology.

Organizational theorists such as Margaret Wheatley have also described the workings of organizational systems in new metaphoric contexts, such as quantum physics, chaos theory, and the self-organization of systems.

Pure logical systems

There is also such a thing as a logical system. The most obvious example is the calculus developed simultaneously by Leibniz and Isaac Newton. Another example is George Boole's Boolean operators. Other examples have related specifically to philosophy, biology, or cognitive science. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs applies psychology to biology by using pure logic.[disambiguation needed] Numerous psychologists, including Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud have developed systems which logically organize psychological domains, such as personalities, motivations, or intellect and desire. Often these domains consist of general categories following a Corollary such as a Theorem. Logic has been applied to categories such as Taxonomy, Ontology, Assessment[disambiguation needed], and Hierarchies.

Systems applied to strategic thinking

In 1988, military strategist, John A. Warden III introduced his Five Ring System model in his book, The Air Campaign contending that any complex system could be broken down into five concentric rings. Each ring—Leadership, Processes, Infrastructure, Population and Action Units—could be used to isolate key elements of any system that needed change. The model was used effectively by Air Force planners in the First Gulf War.[13][14][15] In the late 1990s, Warden applied this five ring model to business strategy.[16]

See also

- Examples of systems

- List of systems (WikiProject)

- physical system

- conceptual system

- Complex system

- Formal system

- Information system

- Meta-system

- Solar System

- Systems in human anatomy

- Market

- Theories about systems

- Chaos theory

- Cybernetics

- Systems ecology

- Systems engineering

- Systems psychology

- Systems theory

- Thermodynamic systems

- Control theory

- Related topics

- Glossary of systems theory

- Complexity theory and organizations

- Black box

- System of systems (engineering)

- Systems art

References

- ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/system

- ^ "σύστημα", Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon, on Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Marshall McLuhan in: McLuhan: Hot & Cool. Ed. by Gerald Emanuel Stearn. A Signet Book published by The New American Library, New York, 1967, p. 288.

- ^ 1945, Zu einer allgemeinen Systemlehre, Blätter für deutsche Philosophie, 3/4. (Extract in: Biologia Generalis, 19 (1949), 139–164.

- ^ 1948, Cybernetics: Or the Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Paris, France: Librairie Hermann & Cie, and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ^ 1956. An Introduction to Cybernetics, Chapman & Hall.

- ^ Steiss 1967, pp. 8–18.

- ^ Bailey, 1994.

- ^ Buckley, 1967.

- ^ Banathy, 1997.

- ^ Klir 1969, pp. 69–72

- ^ Checkland 1997; Flood 1999.

- ^ Warden, John A. III (1988). The Air Campaign: Planning for Combat. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. ISBN 978-1-58348-100-4.

- ^ Warden, John A. III (September 1995). "Chapter 4: Air theory for the 21st century". Battlefield of the Future: 21st Century Warfare Issues (in Air and Space Power Journal). United States Air Force. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ Warden, John A. III (1995). "Enemy as a System". Airpower Journal. Spring (9): 40–55. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ^ Russell, Leland A.; Warden, John A. (2001). Winning in FastTime: Harness the Competitive Advantage of Prometheus in Business and in Life. Newport Beach, CA: GEO Group Press. ISBN 0-9712697-1-8.

Bibliography

- Alexander Backlund (2000). "The definition of system". In: Kybernetes Vol. 29 nr. 4, pp. 444–451.

- Kenneth D. Bailey (1994). Sociology and the New Systems Theory: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis. New York: State of New York Press.

- Bela H. Banathy (1997). "A Taste of Systemics", ISSS The Primer Project.

- Walter F. Buckley (1967). Sociology and Modern Systems Theory, New Jersey: Englewood Cliffs.

- Peter Checkland (1997). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Michel Crozier, Erhard Friedberg (1981). Actors and Systems, Chicago University Press.

- Robert L. Flood (1999). Rethinking the Fifth Discipline: Learning within the unknowable. London: Routledge.

- George J. Klir (1969). Approach to General Systems Theory, 1969.

- Brian Wilson (1980). Systems: Concepts, methodologies and Applications, John Wiley

- Brian Wilson (2001). Soft Systems Methodology—Conceptual model building and its contribution, J.H.Wiley.

- Beynon-Davies P. (2009). Business Information + Systems. Palgrave, Basingstoke. ISBN 978-0-230-20368-6

External links

- Definitions of Systems and Models by Michael Pidwirny, 1999–2007.

- Publications with the title "System" (1600–2008) by Roland Müller.

- Definitionen von "System" (1572–2002) by Roland Müller, (most in German).

- Theory and Practical Exercises of System Dynamics by Juan Martin (also in Spanish).