Jewellery

Jewellery (Jewelry in American English) is literally any piece of fine material used to adorn one’s self. The word jewellery is derived from the word jewel, which was anglicised from the Old French "jouel" in around the 13th century. Further tracing leads back to the Latin word "jocale", meaning plaything.

Jewellery has probably been around since the dawn of man; indeed, recently found 100,000 year-old Nassarius shells that were made into beads are thought to be the oldest known jewellery.[1] Although in earlier times jewellery was created for more practical uses, such as pinning clothes together, in recent times it has been used almost exclusively for decoration. The first pieces of jewellery were made from natural materials, such as bone and animal teeth, shell, wood and carved stone. Jewellery was often made for people of high importance to show their status and in many cases, they were buried with it.

Jewellery is made out of almost every material known and has been made to adorn nearly every body part, from hairpins to toe rings and many more types of jewellery. While high-quality and artistic pieces are made with gemstones and precious metals, less costly costume jewellery is made from less valuable materials and is mass-produced.

Form and function

Over time, jewellery has been used for a number of reasons:

- currency, wealth display and storage,

- functional use (such as clasps, pins, and buckles)

- symbolism (to show membership or status)

- protection (in the form of amulets and magical wards), and

- artistic display

Most cultures have at some point had a practice of keeping large amounts of wealth stored in the form of jewellery. Numerous cultures move wedding dowries in the form of jewelry, or create jewelry as a means to store or display coins. Alternatively, jewellery has been used as a currency or trade good; a particularly poignant example being the use of slave beads

Functional use dates back to the earliest days of jewellery; indeed, many items of jewelry, such as brooches and buckles originated as purely functional items, became more decorated over time, and in some cases became purely art objects as their functional requirement disappeared.

Jewellery can also be symbolic of group membership, as in the case of the Christian crucifix or Jewish Star of David, or status, as in the case of chains of office, or the Western practice of married people wearing a wedding ring.

Wearing of amulets and devotional medals to provide protection or ward off evil is nearly universal; these may take the form of symbols (such as the ankh), stones, plants, animals, body parts (such as the Khamsa), or glyphs (such as stylized versions of the Throne Verse in Islamic art).[2]

Although artistic display has clearly been a function of jewellery from the very beginnings, the other roles described above tended to take primacy. It was only in the late 19th century, with the work of such masters as Peter Carl Fabergé and René Lalique, that art began to take primacy over function and wealth. This trend has continued into modern times, expanded upon by artists such as Robert Lee Morris.

Materials and methods

In creating jewellery, a variety of gemstones, coins or other precious items can be used, often set into precious metals. Common precious metals used for modern jewellery include gold, platinum or silver; although alloys of nearly every metal known can be encountered in jewellery - bronze, for example, was common in Roman times. Most gold alloys used in jewellery range from 10K to 22K gold (24K or pure gold is generally to soft for jewellery use), while platinum alloys range from 900 (90% pure) to 950 (95.0% pure). The silver used in jewellery is usually sterling silver.

Other commonly used materials include glass, such as fused glass or enamel; wood, often carved or turned; shells and other natural animal substances such as bone and ivory; natural clay, polymer clay, and even plastics.

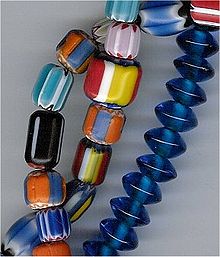

Beads are frequently used in jewellery. These may be made of many different substances including glass, gemstones, metal, wood, shells, clay and polymer clay. Beaded jewellery commonly encompasses necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and belts. Beads may be large or small. The smallest type of beads commonly used are known as seed beads; these are the beads used for the "woven" style of beaded jewellery.

Silversmiths, goldsmiths, and lapidaries use numerous methods to create jewellery, including forging, casting, soldering or welding, cutting, carving, and "cold-joining" (using adhesives, staples, and rivets to assemble parts)[3].

Diamonds

Diamonds, long considered the most prized of gemstones, were first mined in India. Pliny may have mentioned them, although there is some debate as to the exact nature of the stone he referred to as Adamas[4] ; Currently, Africa and Canada rank among the primary sources.

The British crown jewels contain the Cullinan Diamond, part of the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found (1905), at 3,106.75 carats. Now popular in engagement rings, this usage dates back to the marriage of Maximilian I to Mary of Burgundy in 1477.

Diamonds have long been associated with social issues; in South Africa, diamonds and gold were factors in the start of the Second Boer War in the 1890s, they later factored in treatment of blacks during the apartheid era, and have since been instrumental in exacerbating and prolonging other African conflicts (see Blood diamonds).

Jewellery and Society

One universal factor is control over who could wear what jewellery; a point which indicates the powerful symbolism the wearing of jewellery evoked. In ancient Rome, for instance, only certain ranks could wear rings [5]; later, sumptuary laws dictated who could wear what type of jewellery; again based on rank. Cultural dictates have also played a significant role; for example, the wearing of earings by Western men was considered "effeminate" in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Conversely, the jewellery industry in the early 20th century launched a campaign to popularize wedding rings for men — which caught on — as well as engagement rings for men (which did not), going so far as to create a false history and claim that the practice had medieval roots. By the mid 1940s, 85% of weddings in the US featured a double ring ceremony; up from 15% in the 1920s[6]. . Religion has also played a role: Islam for instance considers the wearing of gold by men as Haram[7], and many religions have edicts against excessive display.[8]

History of jewellery

The history of jewellery is a long one, with many different uses among different cultures. It has shaped the course of history and provides various insights into how ancient cultures worked.

Early jewellery

The first signs of jewellery came from the Cro-Magnons, ancestors of Homo sapiens, around 40,000 years ago. The Cro-Magnons originally migrated from the Middle East to settle in Europe and replace the Neanderthals as the dominant species. The jewellery pieces they made were crude necklaces and bracelets of bone, teeth and stone hung on pieces of string or animal sinew, or pieces of carved bone used to secure clothing together. In some cases, jewellery had shell or mother-of-pearl pieces. In southern Russia, carved bracelets made of mammoth tusk have been found. Most commonly, these have been found as grave-goods. Around 7,000 years ago, the first sign of copper jewellery was seen. [9]

Pre-rennaisance Europe and the Middle East

Jewellery in Egypt

The first signs of established jewellery making in Ancient Egypt was around 3,000-5,000 years ago. The Egyptians preferred the luxury, rarity, and workability of gold over other metals. Predynastic Egypt had already acquired much gold; although the Egyptians acquired gold from the eastern deserts of Africa and from Nubia, in later years they captured it in the spoils of war or were gifted it in tributes from other nations.

Jewellery in Egypt soon began to symbolise power and religious power in the community. Although it was worn by wealthy Egyptians in life, it was also worn by them in death; with jewellery commonly seen among Grave goods. Unfortunately, due to graver-robbers much of this has been lost to history.

In conjunction with gold jewellery, Egyptians used coloured glass in place of precious gems. Although the Egyptians had access to gemstones, they preferred the colours they could create in glass over the natural colours of stones. For nearly each gemstone, there was a glass formulation used by the Egyptians to mimic it. The colour of the jewellery was very important, as different colours meant different things; the Book of the Dead dictated that the necklace of Isis around a mummy’s neck must be red to satisfy Isis’s need for blood, while green jewellery meant new growth for crops and fertility. Although lapis lazuli and silver had to be imported from beyond the country’s borders, most other materials for jewellery were found in or near Egypt, for example in the Red Sea, where the Egyptians mined Cleopatra's favourite gem, the emerald.

Egyptian jewellery was predominantly made in large workshops attached to temples or palaces.

Egyptian designs were most common in Phoenician designs. Also, ancient Turkish designs found in Persian jewellery suggests trading from the Middle East into Europe was not uncommon. Women used to wear elaborate gold and silver pieces that were used in ceremonies.

Mesopotamia

By approximately 4,000 years ago, jewellery-making had become a significant craft in the cities of Sumer and Akkad. The most significant archaeological evidence comes from the Royal Cemetery of Ur, where hundreds of burials dating 2900–2300 BC were unearthed; tombs such as that of Puabi contained a multitude of artifacts in gold, silver, and semi-precious stones, such as lapis lazuli crowns embellished with gold figurines, close-fitting collar necklaces, and jewel-headed pins. In Assyria, men and women both wore extensive amounts of jewellery, including amulets, ankle bracelets, heavy multistrand necklaces, and cylinder seals.[10]

Jewellery in Mesopotamia tended to be manufactured from thin metal leaf and was set with large numbers of brightly-colored stones (chiefly agate, lapis, carnelian, and jasper). Favored shapes included leaves, spirals, cones, and bunches of grapes. Jewellers created works both for human use and for adorning statues and idols; they employed a wide variety of sophisticated metalworking techniques, such as cloisonne, engraving, fine granulation, and filigree.[11]

Extensive and meticulously maintained records pertaining to the trade and manufacture of jewellery have also been unearthed throughout Mesopotamian archaological sites. One record in the Mari royal archives, for example, gives the composition of various items of jewellery:

1 necklace of flat speckled chalcedony beads including: 34 flat speckled chalcedony bead, [and] 35 gold fluted beads, in groups of five.

1 necklace of flat speckled chalcedony beads including: 39 flat speckled chalcedony beads, [with] 41 fluted beads in a group that make up the hanging device.

1 necklace with rounded lapis lazuli beads including: 28 rounded lapis lazuili beads, [and] 29 flutd beads for its clasp.[12]

Jewellery in Greece

The Greeks started using gold and gems in jewellery in 1,400 BC, although beads shaped as shells and animals were produced widely in earlier times. By 300 BC, the Greeks had mastered making coloured jewellery and using amethysts, pearl and emeralds. Also, the first signs of cameos appeared, with the Greeks creating them from Indian Sardonyx, a striped brown pink and cream agate stone. Greek jewellery was often simpler than in other cultures, with simple designs and workmanship. However, as time progressed the designs grew in complexity different materials were soon utilized.

Jewellery in Greece was hardly worn and was mostly used for public appearances or on special occasions. It was frequently given as a gift and was predominantly worn by woman to show their wealth, social status and beauty. The jewellery was often supposed to give the wearer protection from the “Evil Eye” or endowed the owner with supernatural powers, while others had a religious symbolism. Older pieces of jewellery that have been found were dedicated to the Gods. Most of these pieces have vanished, but lists of them still exist in places such as the Parthenon. The largest production of jewellery in these times came from Northern Greece and Macedon, where they had higher supplies of gold & the aristocracy could afford the price of jewellery. However, although much of the jewellery in Greece was made of gold and silver with ivory and gems, bronze and clay copies were made also. This allowed citizens of lower social status to buy jewellery too. Due to the lesser quality of the materials, few of these pieces have survived. Unlike gold, which was imported or mined in the north, silver was much more abundant in Greece, making it cheaper to buy.

Ancient jewellery makers in Greece were largely anonymous. They worked the types of jewellery into two different styles of pieces; cast pieces and pieces hammered out of sheet metal. Fewer pieces of cast jewellery have been recovered; it was made by casting the metal onto two stone or clay moulds. Then the two halves were joined together and wax and then molten metal, was placed in the centre. This technique had been in practised since the late Bronze Age. The more common form of jewellery was the hammered sheet type. Sheets of metal would be hammered to the right thickness & then soldered together. The inside of the two sheets would be filled with wax or another liquid to preserve the metal work. Different techniques, such as using a stamp or engraving, were then used to create motifs on the jewellery. Jewels may then be added to hollows or glass poured into special cavities on the surface.

The Greeks took much of their designs from outer origins, such as Asia when Alexander the Great conquered part of it. In earlier designs, other European influences can also be detected. When Roman rule came to Greece, no change in jewellery designs was detected. However, by 27 BC, Greek designs were heavily influenced by the Roman culture. That is not to say that indigenous design did not thrive; numerous polychrome butterfly pendants on silver foxtail chains, dating from the 1st Ccentury, have been found near Olbia, with only one example ever found anywhere else[13].

Other than wearing the jewellery in life, the Greeks also placed many pieces of jewellery in their graves. Unlike the Egyptians who believed one could take their fortune into the afterlife, the Greeks placed the jewellery in graves simply to honour the dead.[14][15]

Jewellery in Rome

Although jewellery work was abundantly diverse in earlier times, especially among the barbarian tribes such as the Celts, when the Romans conquered most of Europe, jewellery was changed as smaller factions developed the Roman designs. The most common artefact of early Rome was the brooch, which was used to secure clothing together. The Romans used a diverse range of materials for their jewellery from their extensive resources across the continent. Although they used gold, they sometimes used bronze or bone and in earlier times, glass beads & pearl. As early as 2,000 years ago, they imported Sri Lankan sapphires and Indian diamonds and used emeralds and amber in their jewellery. In Roman-ruled England, fossilized wood called jet from Northern England was often carved into pieces of jewellery. The early Italians worked in crude gold and created clasps, necklaces, earrings and bracelets. They also produced larger pendants which could be filled with perfume.

Like the Greeks, often the purpose of Roman jewellery was to ward off the “Evil Eye” given by other people. Although woman wore a vast array of jewellery, men often only wore a finger ring. Although they were expected to wear at least one ring, some Roman men wore a ring on every finger, while others wore none. Roman men and women wore rings with a carved stone on it that was used with wax to seal documents, an act that continued into medieval times when kings and noblemen used the same method. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the jewellery designs were absorbed by neighbouring countries and tribes.[16]

Medieval Jewellery

Post-Roman Europe continued to develop jewellery making skills; the Celts and Merovingians in particular are noted for their jewellery, which in terms of quality matched or exceeded that of Byzantium. Clothing fasteners, amulets, and to a lesser extent signet rings are the most common artefacts known to us; a particularly striking celtic example is the Tara Brooch. The Torc was common throughout Europe as a symbol of status and power. By the 8th century, jewelled weaponry was common for men, while other jewellery (with the exception of signet rings) seems to become the domain of women. Grave goods found in a 6th-7th century burial near Chalon-sur-Saône are illustrative; the young girl was buried with: 2 silver fibulae, a necklace (with coins), bracelet, gold earings, a pair of hair-pins, comb, and buckle [17]. The Celts specialized in continuous patterns and designs; while Merovignian designs are best known for stylized animal figures.[18] They were not the only groups known for high quality work; note the Visigoth work shown here, and the numerous decorative objects found at the Anglo-Saxon Ship burial at Sutton Hoo Suffolk, England, are a particularly well-known example.[16]

The Eastern successor of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire, continued many of the methods of the Romans, though religious themes came to predominate. Unlike the Romans, the Frankish, and the Celts, however, Byzantium used light-weight gold leaf rather than solid gold, and more emphasis was placed on stones and gems. As in the West, Byzantine jewellery was worn by wealthier females, with male jewellery apparently restricted to signet rings. Like other contemporary cultures, jewellery was commonly buried with its owner. [19]

Jewellery in Asia

Jewellery making in Asia started in China 5,000 years ago and in the Indus Valley region later on. With roots set deep in religious designs, Asian jewellery was very decorative and used most often in ceremonies.

Jewellery in China

The earliest culture to begin making jewellery in Asia was the Chinese around 5,000 years ago. Chinese jewellery designs were very religion-orientated and contained many Buddhist symbols, a fact which remains to this day.

The Chinese used silver in their jewellery more often than gold, and decorated it with their favourite colour, blue. Blue kingfisher feathers were tied onto early Chinese jewellery and later, blue gems and glass were incorporated into designs. However, Chinese preferred jade over any other stone. They fashioned it using diamonds, as indicated in finds from areas in the country. The Chinese revered jade because of the human-like qualities they assigned to it, such as its hardness, durability and beauty.[9] The first jade pieces were very simple, but as time progressed, more complex design evolved. Jade rings from beween the 4th and 7th centuries BCE show evidence of having been worked with a compound milling machine; hunderds of years before the first mention of such equipment in the west.[20]

In China, jewellery was worn frequently by both sexes to show their nobility and wealth. However, in later years, it was used to accentuate beauty. Woman wore highly detailed gold and silver head dresses and numerous other items, while men wore decorative hat buttons which showed rank and gold or silver rings. Woman also wore strips of gold on their foreheads, much like women in the Indus Valley. The band served a purpose like an early form of tiara and it was often decorated with precious gems. The most common piece of jewellery worn by Chinese was the earring, which was worn by both men and women. Amulets were also common too, often with a Chinese symbol or dragon. In fact, dragons, Chinese symbols and also phoenixes were frequently depicted on jewellery designs.

The Chinese often placed their jewellery in their graves; most Chinese graves found by archaeologists contain decorative jewellery.[21]

Jewellery in the Indus Valley

One of the first to start jewellery making were the peoples of the Indus Valley region. By 1,500 BC the peoples of the Indus Valley were creating gold earrings and necklaces, bead necklaces and metallic bangles. Before 2,100 BC, prior to the period when metals were widely used, the largest jewellery trade in the Indus Valley region was the bead trade. Beads in the Indus Valley were made using simple techniques. First, a bead maker would need a rough stone, which would be bought from an eastern stone trader. The stone would then be placed into a hot oven where it would be heated until it turned deep red, a colour highly prized by people of the Indus Valley. The red stone would then be chipped to the right size and a hole drilled through it with primitive drills. The beads were then polished. Some beads were also painted with designs. This art form was often passed down through family; children of bead makers often learnt how to work beads from a young age.

Jewellery in the Indus Valley was worn predominantly by females, who wore numerous clay or shell bracelets on their wrists. They were often shaped like doughnuts and painted black. Over time, clay bangles were discarded for more durable ones. In India today, bangles are made out of metal or glass. Other pieces that women frequently wore were thin bands of gold that would be worn on the forehead, earrings, primitive brooches, chokers and gold rings. The people of the region were much more urbanised than the rest of the area, so the jewellery worn was of heavier make once the civilization developed. Although women wore jewellery the most, some men in the Indus Valley wore beads. Small beads were often crafted to be placed in men and women’s hair. The beads were so small they usually measured in at only 1 millimetre long.

Unlike many other cultures, Indus Valley jewellery was never buried with the dead. Instead, jewellery was passed down to children or family. Nobility and goldsmiths often hid their jewellery under their floorboards to avoid theft.

As time progressed, the methods for jewellery advanced, thus allowing complex jewellery to be made. Necklaces were soon adorned with gems and green stone.

Although they used other gems prior, India was the first country to mine diamonds, with some mines dating back to 296 BC. However, axes dating to 4,000 BC found in China from previous factions of the country, contain traces of diamond dust used to sharpen the blades. While China used the diamonds they found mainly for carving jade, India traded the diamonds, realising their valuable qualities. This trade almost vanished 1,000 years after Christianity grew as a religion, as Christians rejected the diamonds which were used in Indian religious amulets. Along with Arabians from the Middle East restricting the trade, India’s diamond jewellery trade lulled.

Today, many of the jewellery designs and traditions are still used and jewellery is commonplace in Indian ceremonies and weddings.[21]

Jewellery in the Americas

Jewellery played a major role in the fate of the Americas when the Spanish established an empire to seize South American gold. Jewellery making developed in the Americas 5,000 years ago in Central and South America. Large amounts of gold was easily accessible, and the Aztecs andMayans created numerous works in the metal. Among the Aztecs, only nobility wore gold jewellery, as it showed their rank, power and wealth. Gold jewellery was most common in the Aztec Empire and was often decorated with feathers from birds. The main purpose of Aztec jewellery was to draw attention, with richer and more powerful Aztecs wearing brighter, more expensive jewellery and clothes. Although gold was the most common and popular material used in Aztec jewellery, silver was also readily available throughout the American empires. In addition to adornment and status, the Aztecs also used jewellery in sacrifices to appease the gods. Priests also used gem encrusted daggers to perform animal and humen sacrifices.[16][22]

Another ancient American civilization with expertise in jewellery making was the Maya. At the peak of their civilization, the Maya were making beautiful jewellery from jade, gold, silver, bronze and copper. Maya designs were similar to those of the Aztecs, with lavish head dresses and jewellery. The Maya also traded in precious gems. However, in earlier times, the Maya had little access to metal, so made the majority of their jewellery out of bone or stone. Merchants and nobility were the only few that wore expensive jewellery in the Maya Empire, much the same as with the Aztecs.[21]

In North America, Native Americans used shells, wood, turquoise, and soapstone, almost unavailable in South and Central America. The Native Americans utilized the properties of the stone and used it often in their jewellery, particularly in earlier periods. The turquoise was used in necklaces and to be placed in earrings. Native Americans with access to oyster shells, often located in only one location in American, traded the shells with other tribes, showing the great importance of the body adornment trade in Northern America. [23].

Although initially of interest either as a curiosity or a source of raw material, jewellery designs from the Americas has come to play a significant role in modern jewellery ( see below).

Jewellery in the Pacific

Jewellery making in the Pacific started later than in other areas due to relatively reecnt human settlement. Early jewellery was likely made of bone and wood, and has not survived. One notable exception to this is New Zealand, where the Maori create Hei-tiki. The reason the hei-tiki is worn is not apparent, it may either relate to ancestral connections, as Tiki was the first Maori, or fertility, as there is a strong connection between this and Tiki. Hei-tikis are traditionally carved by hand from nephrite or bowenite; a lengthy and spiritual process.

Post-rennaissance Europe

Jewellery in France

When the Renaissance hit France in the 17th century AD, the art of jewellery making flourished. Although France was the lead producer of fake jewellery at the time, French jewellers made many beautiful pieces. For example, one of the most beautiful and one of the most famous pieces of French jewellery is the Hope Diamond, which is currently housed in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.[24][22]

When Napoleon was crowned as Emperor of France in 1804, he revived the style and grandeur of jewellery and fashion in France. The styles created were soon copied by other European nations, especially England. Under Napoleon’s rule, jewellers introduced parures, a suit of matching jewellery, such as a diamond tiara, diamond earrings, diamond rings, a diamond brooch and a diamond necklace. Both of Napoleon’s wives had beautiful sets such as these and wore them regularly. Another fashion trend resurrected by Napoleon was the cameo. Soon after his cameo decorated crown was seen, cameos were highly sought after.

Although many French pieces were beautifully made with expensive materials, many jewellers in France used cheaper materials, such as fish scale covered glass beads in place of pearls or conch shell cameos instead of stone cameos. Jewellers who worked in cheaper materials were called “bijoutiers”, while jewellers who worked with expensive materials were called “joailliers”.

Jewellery in England

The most famous pieces of English jewellery are undoubtedly the English Crown Jewels. Although all the pieces are beautiful, the most stunning piece is the Sceptre with the Cross and the Cullinan Diamond, the largest rough-gem quality diamond ever found. It was found in South Africa on the Premier Diamond Mining Company in Cullinan, Gauteng, South Africa in 1905. The diamond was brought by the Transvaal government and given to King Edward VII. It was then cut into three pieces and then into eleven smaller pieces. The largest piece is the Cullinan I Diamond, also called the Great Star of Africa, on the Sceptre. To keep the diamond safe on its trip to England, it was put through normal parcel post in a cardboard box, while a fake gem was placed on a high security steamer. The Sceptre and the rest of the crown jewels, as well as some of the other pieces of the Cullinan Diamond, are all currently on display at the Tower of London.

Romanticism

Starting in the late 18th century, Romanticism had a profound impact on the development of western jewellery. Perhaps the most significant influences were the public’s fascination with the treasures being discovered through the birth of modern archaeology, and the fascination with Medieval and Renaissance art. Changing social conditions and the onset of the industrial revolution also lead to growth of a middle class that wanted and could afford jewellery. As a result, the use of industrial processes, cheaper alloys, and stone substitutes, lead to the development of paste or costume jewellery. Distinguished goldsmiths continued to flourish, however, as wealthier patrons sought to ensure that what they wore still stood apart from the jewellery of the masses, not only through use of precious metals and stones but also though superior artistic and technical work; one such artist was the French goldsmith Françoise Désire Fromment Meurice. A category unique to this period and quite appropriate to the philosophy of romanticism was mourning jewellery. It originated in England, where Queen Victoria was often seen wearing jet jewellery after the death of Prince Albert; and allowed the wearer to continue wearing jewellery while expressing a state of mourning at the death of a loved one. [22]

In the United states, this period saw the founding in 1837 of Tiffany & Co. by Charles Lewis Tiffany. Tiffany's put the United States on the world map in terms of jewellery, and gained fame creating dazzling commissions for people such as the wife of Abraham Lincoln; later it would gain popular notoriety as the setting of the film Breakfast at Tiffany's. In France, Pierre Cartier founded Cartier SA in 1847, while 1884 saw the founding of Bulgari in Italy. The modern production studio had been born; a step away from the former dominance of individual craftsmen and patronage.

This period also saw the first major collaboration between East and West; collaboration in Pforzheim between German and Japanese artists lead to Shakudo plaques set into Filigree frames being created by the Stoeffler firm in 1885) [25]. Perhaps the grand finale – and an appropriate transition to the following period – were the masterful creations of the French artist Peter Carl Fabergé, working for the Imperial Russian court, whose Fabergé eggs and jewellery pieces are still considered as the epitome of the goldsmith’s art.

Art Nouveau

In the 1890s, jewellers began to explore the potentials of the growing Art Nouveau style. Very closely related were the German Jugendstil, British (and to some extent American) Arts and Crafts movement. René Lalique, working for the Paris shop of Samuel Bing, was recognized by contemporaries as a leading figure in this trend. The Darmstadt artists colony and Wiener Werkstaette provided perhaps the most significant German input to the trend, while in Denmark Georg Jensen –though best known for his Silverware also contributed significant pieces/ In England, Liberty & Co and the British arts & crafts movement of Charles Robert Ashbee contributed slightly more linear but still characteristic designs. The new style moved the focus of the jeweller's art from the setting of stones to the artistic design of the piece itself; Lalique's famous dragonfly design is one of the best examples of this. Enamels played a large role in technique, while sinuous organic lines are the most recognizable designb feature. The end of World War One once again changed public attitudes; and a more sober style was set to take center-stage.[26]

Modern Jewellery

The jewellery as art movement, spearheaded by artisans such as Robert Lee Morris, has kept jewellery on the leading edge of artistic design. Influence from other cultural forms is also evident; one example of this is bling-bling style jewellery, popularized by hip-hop and rap artists in the early 21st century.

The advent of new materials, such as plastics, Precious Metal Clay (PMC) and different colouring techniques, has led to increased variety in styles. Other advances, such as the development of improved pearls harvesting by people such as Kokichi Mikimoto, and the development of improved quality artificial gemstones such as moissanite (a synthetic diamond) has placed jewellery within the economic grasp of a much larger segment of the population. The late 20th century saw the blending of European design with oriental techniques such as Mokume-gane. Tim McCreight, an eminent authour and silversmith, cites the following as the primary innovations in the decades stadling the year 2000: "Mokume-gane, hydraulic die forming, anti-clastic raising, fold-forming, reactive metal anodizing, shell forms, PMC, photoetching, and [use of] CAD/CAM."[27]

Among early 21st century developments, several jewellers have experimented with ephemeral edible jewellery; including necklaces made of bread and silver rings encrusted with crystalized sugar. [28]

Jewellery and body modification

It can be difficult to determine where jewellery leaves off and body modification takes over. Padaung women in Myanmar place large golden rings around their necks. From as early as 5 years old, girls are introduced to their first neck ring. Over the years, more rings are added. In addition to the twenty-plus pounds of rings on her neck, a woman will also wear just as many rings on her calves too. At their extent, some necks modified like this can reach 10-15 inches long; the practice has obvious health impacts, however, and has in recent years declined from cultural norm to tourist curiosity. [29]. Tribes related to the Paduang, as well as other cultures throughout the world, use jewellery to stretch their earlobes, or enlarge ear piercings. In the Americas, labrets have been worn since before first contact by innu and first nations peoples of the northwest coast[30]. Lip plates are worn by the African Mursi and Sara people, as well as some South American peoples.

In the late 20th century, the influence of modern primitivism led to many of these practices being incorporated into western subcultures. Many of these practices rely on a combination of body modification and decorative objects; thus keeping the distinction between these two types of decoration blurred. As with other forms of jewellery, the crossing of cultural boundaries is one of the more significant features of the artform in the early 21st century,

In popular culture

In line with the significance rings and amulets have played historically, it is not unusual that this should have been copied in fiction. Perhaps the most well-known example is J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings trilogy. The Green Lantern graphic novel is another common example.

Computer role-playing games also commonly use rings, bracelets, and other jewellery as objects embued with special powers.

See also

- List of jewellery types

- Akaoui

- Artisan

- Beauty

- Costume jewellery

- Fashion

- Gemological Institute of America

- Gemstone

- Goldsmithing

- Human physical appearance

- Jewellery cleaning

- Silversmithing

Footnotes

- ^ 22 June, 2006. Study reveals 'oldest jewellery'. BBC News.

- ^ Morris, Desmond. Body Guards: Protective Amulets and Charms. Element, 1999 ISBN 1862045720

- ^ McCreight, Tim. Jewelry: Fundamentals of Metalsmithing. Design Books International, 1997 ISBN 1880140292

- ^ Pliny. Natural History XXXVI, 15

- ^ Pliny the Elder. The Natural History. ed. John Bostock, H.T. Riley, Book XXXIII The Natural History of Metals Online at the Perseus Project Chapter 4. Accessed July 2006

- ^ Howard, Vicky. "A real Man's Ring: Gender and the Invention of Tradition." Journal of Social History, Summer 2003, pp 837-856.

- ^ Yusuf al-Qaradawi. [The Lawful and Prohibited in Islam (online)]

- ^ Greenbaum, Toni. ""SILVER SPEAKS: TRADITIONAL JEWELRY FROM THE MIDDLE EAST". Metalsmith Winter2004, Vol. 24 Issue 1, p56-56. Greenbaum provides the explanation for the lack of historical examples; the majority of Islamic jewellery was in the form of bridal dowries, and traditionally was not handed down from generation to generation; instead, on a woman's death it was sold at the souk and recycled or sold to passer-by. Islamic jewellery from before the 19th century is thus exceedingly rare.

- ^ a b Holland, J. 1999. The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia. Kingfisher books.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat, Daily Life, 155–157.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat, Daily Life, 295–297.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat, Daily Life, 297.

- ^ Treister, Mikhail YU. "Polychrome Necklaces from the Late Hellenistic Period." Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia 2004, Vol. 10 Issue 3/4, p199-257, 59p.

- ^ Gouvoussis, C. Greece. Editions K. Gouvoussis.

- ^ Gouvoussis, C. Athens. Editions K. Gouvoussis.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

last2millionyearswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Duby Georges and Philippe Ariès, eds. A History of Private Life Vol 1 - From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Harvard, 1987. p 506

- ^ Duby, throughout.

- ^ Sherrard, P. 1972. Great Ages of Man: Byzantium. Time-Life International.

- ^ Lu, Peter J., "Early Precision Compound Machine from Ancient China." Science, 6/11/2004, Vol. 304, Issue 5677

- ^ a b c Reader's Digest Association. 1983. Vanished Civilisations. Reader's Digest.

- ^ a b c Farndon, J. 2001. 1,000 Facts on Modern History. Miles Kelly Publishing.

- ^ Josephy Jr, A.M. 1994. 500 Nations: The Illustrated History of North American Indians. Alfred A. Knopf. Inc.

- ^ Fowler, M. 2002. Hope: Adventures of a Diamond. Ballantine.

- ^ Ilse-Neuman, Ursula. Book review “Schmuck/Jewellery 1840-1940: Highlights from the Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim.’’ ‘’Metalsmith’’. Fall2006, Vol. 26 Issue 3, p12-13, 2p

- ^ Art Nouveau as well as Ilse-Neuman 2006.

- ^ McCrieght, Tim. "What's New?" Metalsmith Spring 2006, Vol. 26 Issue 1, p42-45, 4p

- ^ Tanguy, Sarah. "Edible Jewelry." Metalsmith, Spring 2005, Vol. 25 Issue 2, p14-15, 2p, 7c. The food-related work of six jewellers is explored in this article, the examples cited created by Maru Almeida and Charles Lewton-Brain respectively.

- ^ Packard, M. 2002. Ripley's Believe it or not: Special Edition. Scholastic Inc. 22.

- ^ Moss, Madonna L. "George Catlin among the Nayas: Understanding the practice of labret wearing on the Northwest Coast." Ethnohistory Winter99, Vol. 46 Issue 1, p31, 35p

References

- Borel, F. 1994. The Splendor of Ethnic Jewelry: from the Colette and Jean-Pierre Ghysels Collection. New York: H.N. Abrams. (ISBN 0810929937).

- Evans, J. 1989. A History of Jewellery 1100-1870. (ISBN 0486261220).

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea 1998. Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. (ISBN 0313294976).

- Tait, H. 1986. Seven Thousand Years of Jewellery. London: British Museum Publications. (ISBN 0714120340).