Hypericum perforatum

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (December 2013) |

| Hypericum perforatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | H. perforatum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hypericum perforatum | |

Hypericum perforatum, known as Perforate St John's-wort,[1] Common Saint John's wort and St John's wort [note 1], is a flowering plant of the genus Hypericum and a medicinal herb with antidepressant activity and potent anti-inflammatory properties as an arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor and COX-1 inhibitor.[3][4][5] In common speech, the term "St John's wort" may be used to refer to any species of the genus Hypericum. Therefore, Hypericum perforatum is sometimes called "Common St John's wort" or "Perforate St John's wort" in order to differentiate it.

Some studies have supported the use of St John's wort preparations as a treatment for depression in humans.[5][6] In contrast, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine of the United States National Institutes of health warns that St. John's wort is not a proven treatment for depression, that it has many drug-drug interactions that can reduce the effectiveness of other medications, and that psychosis can occur as a rare side effect.[7] The FDA has also warned of the potential of St. John's wort to reduce the effectiveness of other medications.[8]

In certain livestock species, it is toxic when ingested and is also considered a weed when growing wild. Hypericum perforatum is indigenous to Europe but has spread worldwide as an invasive species, including to temperate and subtropical regions of Turkey, Ukraine, Russia, the Middle East, India, Canada, the United States and China.

Botanical description

Hypericum perforatum is a yellow-flowering, stoloniferous or sarmentose, perennial herb indigenous to Europe. It has been introduced to many temperate areas of the world and grows wild in many meadows. The herb's common name comes from its traditional flowering and harvesting on St John's day, 24 June. The genus name Hypericum is derived from the Greek words hyper (above) and eikon (picture), in reference to the plant's traditional use in warding off evil by hanging plants over a religious icon in the house during St John's day. The species name perforatum refers to the presence of small oil glands in the leaves that look like windows, which can be seen when they are held against the light.[2]

St John's wort is a perennial plant with extensive, creeping rhizomes. Its stems are erect, branched in the upper section, and can grow to 1 m high. It has opposing, stalkless, narrow, oblong leaves that are 12 mm long or slightly larger. The leaves are yellow-green in color, with transparent dots throughout the tissue and occasionally with a few black dots on the lower surface.[2] Leaves exhibit obvious translucent dots when held up to the light, giving them a ‘perforated’ appearance, hence the plant's Latin name.

Its flowers measure up to 2.5 cm across, have five petals, and are colored bright yellow with conspicuous black dots. The flowers appear in broad cymes at the ends of the upper branches, between late spring and early to mid summer. The sepals are pointed, with glandular dots in the tissue. There are many stamens, which are united at the base into three bundles. The pollen grains are ellipsoidal.[2]

When flower buds (not the flowers themselves) or seed pods are crushed, a reddish/purple liquid is produced.

-

Full plant

-

Seedlings

-

Fruit

-

Blossom

Ecology

St John's wort reproduces both vegetatively and sexually. It thrives in areas with either a winter- or summer-dominant rainfall pattern; however, distribution is restricted by temperatures too low for seed germination or seedling survival. Altitudes greater than 1500 m, rainfall less than 500 mm, and a daily mean January (in Southern hemisphere) temperature greater than 24 degrees C are considered limiting thresholds. Depending on environmental and climatic conditions, and rosette age, St John's wort will alter growth form and habit to promote survival. Summer rains are particularly effective in allowing the plant to grow vegetatively, following defoliation by insects or grazing.

The seeds can persist for decades in the soil seed bank, germinating following disturbance.[9]

Invasive species

Although Hypericum perforatum is grown commercially in some regions of south east Europe, it is listed as a noxious weed in more than twenty countries and has introduced populations in South and North America, India, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa.[9] In pastures, St John’s wort acts as both a toxic and invasive weed.[10] It replaces native plant communities and forage vegetation to the dominating extent of making productive land nonviable[citation needed] or becoming an invasive species in natural habitats and ecosystems. Ingestion by livestock can cause photosensitization, central nervous system depression, spontaneous abortion, and can lead to death. Effective herbicides for control of Hypericum include 2,4-D, picloram, and glyphosate. In western North America three beetles Chrysolina quadrigemina, Chrysolina hyperici and Agrilus hyperici have been introduced as biocontrol agents.

Livestock

Poisoning

In large doses, St John's wort is poisonous to grazing livestock (cattle, sheep, goats, horses).[10] Behavioural signs of poisoning are general restlessness and skin irritation. Restlessness is often indicated by pawing of the ground, headshaking, head rubbing, and occasional hindlimb weakness with knuckling over, panting, confusion, and depression. Mania and hyperactivity may also result, including running in circles until exhausted. Observations of thick wort infestations by Australian graziers include the appearance of circular patches giving hillsides a ‘crop circle’ appearance, it is presumed, from this phenomenon. Animals typically seek shade and have reduced appetite. Hypersensitivity to water has been noted, and convulsions may occur following a knock to the head. Although general aversion to water is noted, some may seek water for relief.

Severe skin irritation is physically apparent, with reddening of non-pigmented and unprotected areas. This subsequently leads to itch and rubbing, followed by further inflammation, exudation, and scab formation. Lesions and inflammation that occur are said to resemble the conditions seen in foot and mouth disease. Sheep have been observed to have face swelling, dermatitis, and wool falling off due to rubbing. Lactating animals may cease or have reduced milk production; pregnant animals may abort. Lesions on udders are often apparent. Horses may show signs of anorexia, depression (with a comatose state), dilated pupils, and injected conjunctiva.

Diagnosis

Increased respiration and heart rate is typically observed while one of the early signs of St John's wort poisoning is an abnormal increase in body temperature. Affected animals will lose weight, or fail to gain weight; young animals are more affected than old animals. In severe cases death may occur, as a direct result of starvation, or because of secondary disease or septicaemia of lesions. Some affected animals may accidentally drown. Poor performance of suckling lambs (pigmented and non-pigmented) has been noted, suggesting a reduction in the milk production, or the transmission of a toxin in the milk.

Photosensitisation

Most clinical signs in animals are caused by photosensitisation.[11] Plants may induce either primary or secondary photosensitisation:

- primary photosensitisation directly from chemicals contained in ingested plants

- secondary photosensitisation from plant-associated damage to the liver.

Araya and Ford (1981) explored changes in liver function and concluded there was no evidence of Hypericum-related effect on the excretory capacity of the liver, or any interference was minimal and temporary. However, evidence of liver damage in blood plasma has been found at high and long rates of dosage.

Photosensitisation causes skin inflammation by a mechanism involving a pigment or photodynamic compound, which when activated by a certain wavelength of light leads to oxidation reactions in vivo. This leads to lesions of tissue, particularly noticeable on and around parts of skin exposed to light. Lightly covered or poorly pigmented areas are most conspicuous. Removal of affected animals from sunlight results in reduced symptoms of poisoning.

Medical uses

Major depressive disorder

St John's wort is widely known as a herbal treatment for depression. In some countries, such as Germany, it is commonly prescribed for mild to moderate depression, especially in children and adolescents.[12] Specifically, Germany has a governmental organization called Commission E which regularly performs rigorous studies on herbal medicine. It is proposed that the mechanism of action of St. John's wort is due to the inhibition of reuptake of certain neurotransmitters.[2] The best studied chemical components of the plant are hypericin and pseudohypericin.

An analysis of twenty-nine clinical trials with more than five thousand patients was conducted by Cochrane Collaboration. The review concluded that extracts of St John's wort were superior to placebo in patients with major depression. St John's wort had similar efficacy to standard antidepressants. The rate of side-effects was half that of newer SSRI antidepressants and one-fifth that of older tricyclic antidepressants.[13] A report[13] from the Cochrane Review states:

The available evidence suggests that the Hypericum extracts tested in the included trials a) are superior to placebo in patients with major depression; b) are similarly effective as standard antidepressants; and c) have fewer side-effects than standard antidepressants.

In contrast, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the United States National Institutes of health warns that St. John's wort is not a proven treatment for depression, that it has many drug-drug interactions that can reduce the effectiveness of other medications, and that psychosis can occur as a rare side effect.[7] The FDA has also warned of the potential of St. John's wort to reduce the effectiveness of other medications.[8]

Research

St John's wort is being studied for effectiveness in the treatment of certain somatoform disorders. Results from the initial studies are mixed and still inconclusive; some research has found no effectiveness, other research has found a slight lightening of symptoms. Further study is needed and is being performed.

A major constituent chemical, hyperforin, may be useful for treatment of alcoholism, although dosage, safety and efficacy have not been studied.[14][15] Hyperforin has also displayed antibacterial properties against Gram-positive bacteria, although dosage, safety and efficacy has not been studied.[16] Herbal medicine has also employed lipophilic extracts from St John's wort as a topical remedy for wounds, abrasions, burns, and muscle pain.[15] The positive effects that have been observed are generally attributed to hyperforin due to its possible antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects.[15] For this reason hyperforin may be useful in the treatment of infected wounds and inflammatory skin diseases.[15] In response to hyperforin's incorporation into a new bath oil, a study to assess potential skin irritation was conducted which found good skin tolerance of St John's wort.[15]

A randomized controlled trial of St John's wort found no significant difference between it and placebo in the management of ADHD symptoms over eight weeks. However, the St John's wort extract used in the study, originally confirmed to contain 0.3% hypericin, was allowed to degrade to levels of 0.13% hypericin and 0.14% hyperforin. Given that the level of hyperforin was not ascertained at the beginning of the study, and levels of both hyperforin and hypericin were well below that used in other studies, little can be determined based on this study alone.[17] Hypericin and pseudohypericin have shown both antiviral and antibacterial activities. It is believed that these molecules bind non-specifically to viral and cellular membranes and can result in photo-oxidation of the pathogens to kill them.[2]

A research team from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM) published a study entitled "Hypericum perforatum. Possible option against Parkinson's disease", which suggests that St John's wort has antioxidant active ingredients that could help reduce the neuronal degeneration caused by the disease.[18][19][20][21]

Recent evidence suggests that daily treatment with St John's wort may improve the most common physical and behavioural symptoms associated with premenstrual syndrome.[22]

St John's wort was found to be less effective than placebo, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.[23]

St John's wort alleviated age-related long-term memory impairment in rats.[24]

Adverse effects and drug interactions

St John's wort is generally well tolerated, with an adverse effect profile similar to placebo.[25] The most common adverse effects reported are gastrointestinal symptoms, dizziness, confusion, tiredness and sedation.[26][27] It also decreases the levels of estrogens, such as estradiol, by speeding up its metabolism, and should not be taken by women on contraceptive pills as it upregulates the CYP3A4 cytochrome of the P450 system in the liver.[28]

St John's wort may rarely cause photosensitivity. This can lead to visual sensitivity to light and to sunburns in situations that would not normally cause them.[25] Related to this, recent studies concluded that the extract reacts with light, both visible and ultraviolet, to produce free radicals, molecules that can damage the cells of the body. These can react with vital proteins in the eye that, if damaged, precipitate out, causing cataracts.[29] Another study found that in low concentrations, St. John's wort inhibits free radical production in both cell-free and human vascular tissue, revealing antioxidant properties of the compound. The same study found pro-oxidant activity at the highest concentration tested.[30]

St John's wort is associated with aggravating psychosis in people who have schizophrenia.[31]

Consumption of St. John's wort is discouraged for those with bipolar disorder. There is concern that people with bipolar depression taking St. John’s wort may be at a higher risk for mania.[32]

While St. John's wort shows some promise in treating children, it is advised that it be only done with medical supervision. [32]

The interactions that Saint Johns Wort has with other medications is also well studied and has yielded significant results of drug interactions with medications such as Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants, warfarin, and birthcontrol. Combining both SJW and SSRI depressants can lead to increased serotonin levels causing a potentially fatal serotonin syndrome.[33] SJW will reduce the effects of warfarin and lead to thrombosis.[34] Combining estrogen containing oral contraceptives with SJW can lead to decreased efficacy of the contraceptive and eventually unplanned pregnancies.[35] These are just a few of the drug interactions that SJW posess. It is also known to decrease the efficacy of HIV medications, Cholesterol medications, as well as transplant medications.[36] It is because of these dangerous drug interactions that it is imperative to speak with your Doctor or Pharmacist before starting any alternative medicines.

Pharmacokinetic interactions

St John's wort has been shown to cause multiple drug interactions through induction of the cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP2C9, and CYP1A2 (females only). This drug-metabolizing enzyme induction results in the increased metabolism of certain drugs, leading to decreased plasma concentration and potential clinical effect.[37] The principal constituents thought to be responsible are hyperforin and amentoflavone.

St John's wort has also been shown to cause drug interactions through the induction of the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux transporter. Increased P-gp expression results in decreased absorption and increased clearance of certain drugs, leading to lower plasma concentration and potential clinical efficacy.[38]

| Class | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Antiretrovirals | Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors |

| Benzodiazepines | Alprazolam, midazolam |

| Hormonal contraception | Combined oral contraceptives |

| Immunosuppressants | Calcineurin inhibitors, cyclosporine, tacrolimus |

| Antiarrhythmics | Amiodarone, flecainide, mexiletine |

| Beta-blockers | Metoprolol, carvedilol |

| Calcium channel blockers | Verapamil, diltiazem, amlodipine |

| Statins (cholesterol-reducing medications) | Lovastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin |

| Others | Digoxin, methadone, omeprazole, phenobarbital, theophylline, warfarin, levodopa, buprenorphine, irinotecan |

| Reference: Rossi, 2005; Micromedex | |

For a complete list, see CYP3A4 ligands and CYP2C9 ligands.

Pharmacodynamic interactions

In combination with other drugs that may elevate 5-HT (serotonin) levels in the central nervous system (CNS), St John's wort may contribute to serotonin syndrome, a potentially life-threatening adverse drug reaction.[39]

| Class | Drugs |

|---|---|

| Antidepressants | MAOIs, TCAs, SSRIs, SNRIs, mirtazapine |

| Opioids | Tramadol, pethidine (meperidine), Levorphanol |

| CNS stimulants | Phentermine, diethylpropion, amphetamines, sibutramine, cocaine |

| 5-HT1 agonists | Triptans |

| Psychedelic drugs | Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), LSD, Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), MDA, 6-APB |

| Others | Selegiline, tryptophan, buspirone, lithium, linezolid, 5-HTP, dextromethorphan |

| Reference:[39] | |

Detection in body fluids

Hypericin, pseudohypericin, and hyperforin may be quantitated in plasma as confirmation of usage and to estimate the dosage. These three active substituents have plasma elimination half-lives within a range of 15–60 hours in humans. None of the three has been detected in urine specimens.[40]

Chemical constituents

The plant contains the following:[41][42]

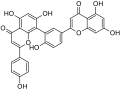

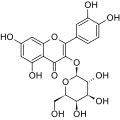

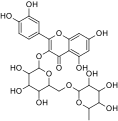

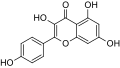

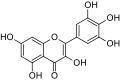

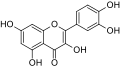

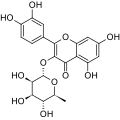

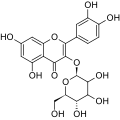

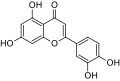

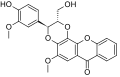

- Flavonoids (e.g. epigallocatechin, rutin, hyperoside, isoquercetin, quercitrin, quercetin, amentoflavone, biapigenin, astilbin, myricetin, miquelianin, kaempferol, luteolin)

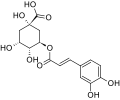

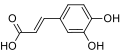

- Phenolic acids (e.g. chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid)

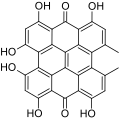

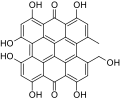

- Naphthodianthrones (e.g. hypericin, pseudohypericin, protohypericin, protopseudohypericin)

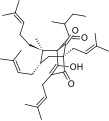

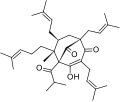

- Phloroglucinols (e.g. hyperforin, adhyperforin)

- Tannins (unspecified, proanthocyanidins reported)

- Volatile oils (e.g. 2-methyloctane, nonane, 2-methyldecane, undecane, α-pinene, β-pinene, α-terpineol, geraniol, myrcene, limonene, caryophyllene, humulene)

- Saturated fatty acids (e.g. isovaleric acid (3-methylbutanoic acid), myristic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid)

- Alkanols (e.g. 1-tetracosanol, 1-hexacosanol)

- Vitamins & their analogues (e.g. carotenoids, choline, nicotinamide, nicotinic acid)

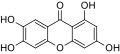

- Miscellaneous others (e.g. pectin, β-sitosterol, hexadecane, triacontane, kielcorin, norathyriol)

The naphthodianthrones hypericin and pseudohypericin along with the phloroglucinol derivative hyperforin are thought to be among the numerous active constituents.[2][43][44][45] It also contains essential oils composed mainly of sesquiterpenes.[2]

-

Pseudohypericin

-

Kielcorin

-

Norathyriol

Mechanism of action

St. John's wort (SJW), similarly to other herbal products, contains a whole host of different chemical constituents that may be pertinent to its therapeutic effects.[41] Hyperforin and adhyperforin, two phloroglucinol constituents of SJW, are TRPC6 receptor agonist and, consequently, they induce noncompetitive reuptake inhibition of monoamines (specifically, dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin), GABA, and glutamate when they activate this receptor.[6][46][47] It inhibits reuptake of these neurotransmitters by increasing intracellular sodium ion concentrations.[6] Moreover, SJW is known to downregulate the β1 adrenoceptor and upregulate postsynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, both of which are a type of serotonin receptor.[6] Other compounds may also play a role in SJW's antidepressant effects such compounds include: oligomeric procyanidines, flavonoids (quercetin), hypericin, and pseudohypericin.[6][48][49][50]

In humans, the active ingredient hyperforin is a monoamine reuptake inhibitor which also acts as an inhibitor of PTGS1, Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase, SLCO1B1 and an inducer of cMOAT.[46][47][51] Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors are typically used to treat asthma, since the enzyme's product, leukotrienes, mediate some of the effects of asthma. Hyperforin is also a powerful anti-inflammatory compound with anti-angiogenic, antibiotic, and neurotrophic properties.[46][47][51] Hyperforin also has an antagonistic effect on NMDA receptors, a type of glutamate receptor.[47] According to one study, hyperforin content correlates with therapeutic effect in mild to moderate depression.[52] Moreover, a hyperforin-free extract of St John's wort (Remotiv) may still have significant antidepressive effects.[53][54] The limited existing literature on adhyperforin suggests that, like hyperforin, it is a reuptake inhibitor of monoamines, GABA, and glutamate.[55]

| Compound | Conc.[41] [42][57] |

log P | PSA | pKa | Formula | MW | CYP1A2 [Note 1] |

CYP2C9 [Note 2] |

CYP2D6 [Note 3] |

CYP3A4 [Note 4] |

PGP [Note 5] |

t1/2[57] (h) | Tmax[57] (h) | Cmax[57] (mM) | CSS[57] (mM) | Notes/Biological activity[Note 6] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phloroglucinols (2-5%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Adhyperforin | 0.2-1.9 | 10-13 | 71.4 | 8.51 | C36H54O4 | 550.81 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Inhibits reuptake of: 5-HT, DA, NE, GABA and Glu via TRPC6 activation[58] |

| Hyperforin | 2-4.5 | 9.7-13 | 71.4 | 8.51 | C35H52O4 | 536.78 | +[59] | +[59]/-[60] | -[60] | + | + | 3.5-16 | 2.5-4.4 | 15-235 | 53.7 | Serves as a TRPC6 and PXR agonist. Reuptake inhibitor of 5-HT (205nM), DA (102nM), NE (80nM), GABA (184nM), Glu (829nM), Gly and Ch (8.5μM). Angiogenesis, COX-1 (300nM), 5-LO (90nM), SIRT1 (15μM), SIRT2 (28μM) and MRSA (1.86μM) inhibitor. |

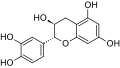

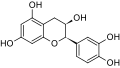

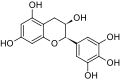

| Naphthodianthrones (0.03-3%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Hypericin[61] | 0.003-3 | 7.5-10 | 156 | 6.9±0.2 | C30H16O8 | 504.44 | 0 | - (3.4 μM) |

- (8.5 μM) | - (8.7 μM) |

? | 2.5-6.5 | 6-48 | 0.66-46 | ? | Is a topoisomerase II,[62] PKA (10μM), PKC (27nM), CK1 (3μM), CK2 (6nM), MAPK (4nM), EGFR (35nM), InsR (29nM), PI3K (180nM), DBH (12.4μM), DNA polymerase A (14.7μM), HIV-1 RT (770nM), COMT, MAOA (68μM) and MAOB (420μM), succinoxidase (8.2μM), GSR (2.1nM), GPx (5.2μM), GST (6.6μM) and CuZnSOD (5.25μM) inhibitor.[57][61] Binds to the NMDA receptor (Ki=1.1μM), μ-opioid, κ-opioid, δ-opioid, 5-HT6, CRF1, NPY-Y1, NPY-Y2 and σ receptors.[61] Exhibits light-dependent inhibitory effects on HIV-1 and cancers.[61] |

| Pseudohypericin | 0.2-0.23 | 6.7±1.8 | 176 | 7.16 | C30H16O9 | 520.44 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 24.8-25.4 | 3 | 1.4-16 | 0.6-10.8[63] | Photosensitiser and antiretroviral like hypericin.[64][65] PKC inhibitory effects in vitro.[66] |

| Flavonoids (2-12%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Amentoflavone [67] |

0.01-0.05 | 3.1-5.1 | 174 | 2.39 | C30H18O10 | 538.46 | ? | - (35 nM) |

- (24.3 μM) | - (4.8 μM) |

? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Serves as a fatty acid synthase (FASN) inhibitor,[68][69][70] kappa opioid antagonist,[71] and a negative allosteric modulator at the benzodiazepine site of the GABAA receptor.[72] |

| Apigenin | 0.1-0.5 | 2.1±0.56 | 87 | 6.63 | C15H10O5 | 270.24 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Benzodiazepine receptor ligand (Ki=4μM) with anxiolytic effects.[73] Also has anti-inflammatory, anticancer, cancer-preventing and antioxidant effects.[74][75] |

| Catechin | 2-4 | 1.8±0.85 | 110 | 8.92 | C15H14O6 | 290.27 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Anticancer, antioxidant, cardioprotective and antimicrobial.[76][77] Cannabinoid receptor CB1 ligand.[78] |

| Epigallocatechin | ? | -0.5-1.5 | 131 | 8.67 | C15H14O6 | 290.27 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 1.7±0.4a | 1.3-1.6a | ? | ? | Found in higher concentrations in Green tea. Antioxidant. CB1 receptor ligand (Ki=35.7 μM).[78] |

| Hyperoside | 0.5-2 | 1.5±1.7 | 174 | 6.17 | C21H20O12 | 464.38 | ? | ? | -[79] (3.87μM) | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Has anti-fungal effects in vitro (against the plant pathogens P. guepini and Drechslera),[80] neuroprotective effects via the PI3K/Akt/Bad/BclXL signalling pathway in vitro,[81] anti-inflammatory effects via NF-κB inhibition in vitro,[82] D2 receptor-dependent antidepressant-like effects in vivo,[83] and antiglucocorticoid-like effects in vitro.[84] |

| Kaempferol[85] | ? | 2.1±0.6 | 107 | 6.44 | C15H10O6 | 286.24 | ? | ? | ? | +/-[Note 7] | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Inhibits the following: inflammation (via NF-κB and STAT1 inhibition),[86] cancer, HDAC,[87] bacteria, viruses, protozoa and fungi.[88] It is also known to prevent cardiovascular disease and cancer.[88] |

| Luteolin | ? | 2.4±0.65 | 107 | 6.3 | C15H10O6 | 286.24 | - | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Has anti-inflammatory, anticancer, anti-allergic and antioxidant effects.[89][90] May also have positive effects on people with autism spectrum disorders.[91] Potent non-selective competitive inhibitor of PDE1-5.[92] |

| Quercetin[93][94] | 2-4 | 2.2±1.5 | 127 | 6.44 | C15H10O7 | 302.24 | - (7.5 μM) b |

- (47 μM) b |

- (24 μM) b |

- (22 μM) b |

- | 20-72c | 8c | ? | ? | Has anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, anti-asthmatic, antihypertensive, analgesic, neuroprotective, gastroprotective, anti-diabetic, cardiovascular disease-preventing, antioxidant, antidepressant-like (in rat models of depression), anxiolytic-like, sedative, antimicrobial and athletic performance-promoting effects.[94] Non-selective PDE1-4 inhibitor that is slightly selective for PDE3/4 over PDE1/2.[95] |

| Rutin | 0.3-1.6 | 1.2±2.1 | 266 | 6.43 | C27H30O16 | 610.52 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Has anticancer, cardioprotective, nephroprotective, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, procognitive and antilipidaemic effects.[96] |

| Phenolic acids (~0.1%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Caffeic acid | 0.1 | 1.4±0.4 | 77.8 | 3.64 | C9H8O4 | 180.16 | ? | ? | ? | -[97] | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Anticancer, hepatoprotective, antibacterial and antioxidant effects reported.[98] |

| Chlorogenic acid | <0.1% | -0.36±0.43 | 165 | 3.33 | C16H18O9 | 354.31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Antibacterial, anticancer and antioxidant effects have been demonstrated.[99] |

| Acronym/Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| MW | Molecular weight in g•mol−1. |

| PGP | P-glycoprotein |

| t1/2 | Elimination half-life in hours |

| Tmax | Time to peak plasma concentration in hours |

| Cmax | Peak plasma concentration in mM |

| CSS | Steady state plasma concentration in mM |

| Partition coefficient. These values are experimental values taken from ChemSpider and [100] (the access dates are both 13–15 December 2013) where available or, if they are not available approximations are taken from [www.chemaxon.com/download/marvin/for-end-users/ ChemAxon MarvinSketch] 6.1.4 & [101] | |

| PSA | Polar surface area of the molecule in question in square angstroms (Å2). Obtained from PubChem (the access date is 13 December 2013). |

| Conc. | These values pertain to the approximation concentration (in %) of the constituents in the fresh plant material |

| - | Indicates inhibition of the enzyme in question. |

| + | Indicates an inductive effect on the enzyme in question. |

| 0 | No effect on the enzyme in question. |

| 5-HT | 5-hydroxytryptamine — synonym for serotonin. |

| DA | Dopamine |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| Glu | Glutamate |

| Gly | Glycine |

| Ch | Choline |

| a | Pharmacokinetic data for ECG comes from a study[102] of its pharmacokinetics after oral administration of green tea. |

| b | Comes from this source.[60] |

| c | Pharmacokinetic data for quercetin comes from a study[103] using pure oral quercetin, not a SJW extract. |

Notes:

- ^ In brackets is the IC50/EC50 value depending on whether it is an inhibitory or inductive action being exhibited, respectively.

- ^ As with last note

- ^ As with last note

- ^ As with last note

- ^ As with last note

- ^ Values given in brackets are IC50/EC50 depending on whether it's an inhibitory or inductive action the compound displays towards the biologic target in question. If it pertains to bacterial growth inhibition the value is MIC50

- ^ Depends on the time frame: short-term administration causes inhibition; long-term causes induction via PXR

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "BSBI List 2007". Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Archived from the original (xls) on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mehta, Sweety (18 December 2012). "Pharmacognosy of St. John's Wort". Pharmaxchange.info. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ "Enzymes". Hyperforin. 3.6. University of Alberta. 30 June 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

Hyperforin is found in alcoholic beverages. Hyperforin is a constituent of Hypericum perforatum (St John's Wort) Hyperforin is a phytochemical produced by some of the members of the plant genus Hypericum, notably Hypericum perforatum (St John's wort). The structure of hyperforin was elucidated by a research group from the Shemyakin Institute of Bio-organic Chemistry (USSR Academy of Sciences in Moscow) and published in 1975. Hyperforin is a prenylated phloroglucinol derivative. Total synthesis of hyperforin has not yet been accomplished, despite attempts by several research groups. Hyperforin has been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, antibiotic and anti-depressant functions (PMID 17696442 , 21751836 , 12725578 , 12018529 )

1. Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase ...Specific function: Catalyzes the first step in leukotriene biosynthesis, and thereby plays a role in inflammatory processes ...

2. Prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 ... General function: Involved in peroxidase activity{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Wölfle U, Seelinger G, Schempp CM (2014). "Topical application of St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum)". Planta Med. 80 (2–3): 109–20. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1351019. PMID 24214835.

Anti-inflammatory mechanisms of hyperforin have been described as inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 (but not COX-2) and 5-lipoxygenase at low concentrations of 0.3 µmol/L and 1.2 µmol/L, respectively [52], and of PGE2 production in vitro [53] and in vivo with superior efficiency (ED50 = 1 mg/kg) compared to indomethacin (5 mg/kg) [54]. Hyperforin turned out to be a novel type of 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor with high effectivity in vivo [55] and suppressed oxidative bursts in polymorphonuclear cells at 1.8 µmol/L in vitro [56]. Inhibition of IFN-γ production, strong downregulation of CXCR3 expression on activated T cells, and downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 expression caused Cabrelle et al. [57] to test the effectivity of hyperforin in a rat model of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE). Hyperforin attenuated the symptoms significantly, and the authors discussed hyperforin as a putative therapeutic molecule for the treatment of autoimmune inflammatory diseases sustained by Th1 cells.

- ^ a b Klemow KM, Bartlow A, Crawford J, Kocher N, Shah J, Ritsick M (2011). "Chapter 11: Medical Attributes of St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum)". In Benzie IFF, Sissi WG (ed.). Herbal Medicine Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects (2nd ed. ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9781439807163. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Nathan PJ (2001). "Hypericum perforatum (St John's Wort): a non-selective reuptake inhibitor? A review of the recent advances in its pharmacology". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 15 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1177/026988110101500109. PMID 11277608.

- ^ a b "National Institute for Complementary and Integrative Health: St. John's Wort". Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Post-marketing safety information: St. John's wort". Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- ^ a b "SPECIES: Hypericum perforatum" (PDF). Fire Effects Information System.

- ^ a b St John's wort

- ^ St John's wort effects on animals

- ^ Fegert JM, Kölch M, Zito JM, Glaeske G, Janhsen K (February–April 2006). "Antidepressant use in children and adolescents in Germany". J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 16 (1–2): 197–206. doi:10.1089/cap.2006.16.197. PMID 16553540.

- ^ a b Linde K, Berner MM, Kriston L (2008). Linde K (ed.). "St John's wort for major depression". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD000448. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000448.pub3. PMID 18843608.

- ^ Kumar V, Mdzinarishvili A, Kiewert C, Abbruscato T, Bickel U, van der Schyf CJ, Klein J (2006). "NMDA receptor-antagonistic properties of hyperforin, a constituent of St. John's Wort" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Sci. 102 (1): 47–54. doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0060378. PMID 16936454.

- ^ a b c d e Reuter J, Huyke C, Scheuvens H, Ploch M, Neumann K, Jakob T, Schempp CM (2008). "Skin tolerance of a new bath oil containing St. John's wort extract". Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 21 (6): 306–311. doi:10.1159/000148223. PMID 18667843.

- ^ Cecchini C, Cresci A, Coman MM, Ricciutelli M, Sagratini G, Vittori S, Lucarini D, Maggi F (2007). "Antimicrobial activity of seven hypericum entities from central Italy". Planta Med. 73 (6): 564–6. doi:10.1055/s-2007-967198. PMID 17516331.

- ^ Weber W, Vander Stoep A, McCarty RL, Weiss NS, Biederman J, McClellan J (2008). "Hypericum perforatum (St John's wort) for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 299 (22): 2633–41. doi:10.1001/jama.299.22.2633. PMC 2587403. PMID 18544723.

- ^ "Medicinal Plant, St John's Wort, May Reduce Neuronal Degeneration Caused By Parkinson's Disease". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ "www.diariocritico.com/general/147916". Diariocritico.com. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "www.madrimasd.org/noticias/-i-Hypericum-perforatum-i-y-Parkinson/38181". Madrimasd.org. 16 February 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ Canning S, Waterman M, Orsi N, Ayres J, Simpson N, Dye L (2010). "The efficacy of Hypericum perforatum (St John's wort) for the treatment of premenstrual syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". CNS Drugs. 24 (3): 207–25. doi:10.2165/11530120-000000000-00000. PMID 20155996.

- ^ Saito YA, Rey E, Almazar-Elder AE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Locke GR, Talley NJ (2010). "A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of St John's wort for treating irritable bowel syndrome". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 105 (1): 170–7. doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.577. PMID 19809408.

- ^ Trofimiuk, E; Braszko, JJ (August 2010). "Hypericum perforatum alleviates age-related forgetting in rats". Current Topics in Nutraceutical Research. 8 (2–3): 103–107.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ernst E, Rand JI, Barnes J, Stevinson C (1998). "Adverse effects profile of the herbal antidepressant St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.)". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 54 (8): 589–94. doi:10.1007/s002280050519. PMID 9860144.

- ^ Barnes, J; Anderson, LA; Phillipson, JD (2002). Herbal Medicines: A guide for healthcare professionals (2nd ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 9780853692898.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parker V, Wong AH, Boon HS, Seeman MV (2001). "Adverse reactions to St John's Wort". Can J Psychiatry. 46 (1): 77–9. PMID 11221494.

- ^ Barr Laboratories, Inc. (March 2008). "ESTRACE TABLETS, (estradiol tablets, USP)" (PDF). wcrx.com. Retrieved 27 January 2010.

- ^ Schey KL, Patat S, Chignell CF, Datillo M, Wang RH, Roberts JE (2000). "Photooxidation of lens alpha-crystallin by hypericin (active ingredient in St. John's Wort)". Photochem. Photobiol. 72 (2): 200–3. doi:10.1562/0031-8655(2000)0720200POLCBH2.0.CO2. PMID 10946573.

- ^ Hunt EJ, Lester CE, Lester EA, Tackett RL (2001). "Effect of St. John's wort on free radical production". Life Sci. 69 (2): 181–90. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(01)01102-X. PMID 11441908.

- ^ Singh, Simon and Edzard Ernst (2008). Trick or Treatment: The Undeniable Facts About Alternative Medicine. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-393-33778-5.

- ^ a b "St. John's wort - University of Maryland Medical Center". University of Maryland Medical Center. umm.edu. 24 June 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ (Borrelli, 2009)

- ^ (Xuemin Jiang, 2004)

- ^ (Russo, Scicchitano et al. 2014)

- ^ (Bailey, 2006)

- ^ Wenk M, Todesco L, Krähenbühl S (2004). "Effect of St John's wort on the activities of CYP1A2, CYP3A4, CYP2D6, N-acetyltransferase 2, and xanthine oxidase in healthy males and females" (PDF). Br J Clin Pharmacol. 57 (4): 495–499. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02049.x. PMC 1884478. PMID 15025748.

- ^ Gurley BJ, Swain A, Williams DK, Barone G, Battu SK (2008). "Gauging the clinical significance of P-glycoprotein-mediated herb-drug interactions: comparative effects of St. John's wort, Echinacea, clarithromycin, and rifampin on digoxin pharmacokinetics". Mol Nutr Food Res. 52 (7): 772–9. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200700081. PMC 2562898. PMID 18214850.

- ^ a b Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1445–1446.

- ^ a b c d Barnes, J; Anderson, LA; Phillipson, JD (2007) [1996]. Herbal Medicines (PDF) (3rd ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-623-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Greeson JM, Sanford B, Monti DA (2001). "St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum): a review of the current pharmacological, toxicological, and clinical literature" (PDF). Psychopharmacology (Berl.). 153 (4): 402–414date=February 2001. doi:10.1007/s002130000625. PMID 11243487.

- ^ Umek A, Kreft S, Kartnig T, Heydel B (1999). "Quantitative phytochemical analyses of six hypericum species growing in slovenia". Planta Med. 65 (4): 388–90. doi:10.1055/s-2006-960798. PMID 17260265.

- ^ Tatsis EC, Boeren S, Exarchou V, Troganis AN, Vervoort J, Gerothanassis IP (2007). "Identification of the major constituents of Hypericum perforatum by LC/SPE/NMR and/or LC/MS". Phytochemistry. 68 (3): 383–93. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.11.026. PMID 17196625.

- ^ Schwob I, Bessière JM, Viano J.Composition of the essential oils of Hypericum perforatum L. from southeastern France.C R Biol. 2002;325:781-5.

- ^ a b c "Pharmacology". Hyperforin. University of Alberta. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Hyperforin. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Nahrstedt A, Butterweck V (1997). "Biologically active and other chemical constituents of the herb of Hypericum perforatum L". Pharmacopsychiatry. 30 Suppl 2 (Suppl 2): 129–34. doi:10.1055/s-2007-979533. PMID 9342774.

- ^ Butterweck V (2003). "Mechanism of action of St John's wort in depression : what is known?" (PDF). CNS Drugs. 17 (8): 539–62. doi:10.2165/00023210-200317080-00001. PMID 12775192.

- ^ Müller WE (2003). "Current St John's wort research from mode of action to clinical efficacy". Pharmacol. Res. 47 (2): 101–9. doi:10.1016/S1043-6618(02)00266-9. PMID 12543057.

- ^ a b "Targets". Hyperforin. University of Alberta. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "St. John's wort in mild to moderate depre... [Pharmacopsychiatry. 1998] - PubMed - NCBI". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ Woelk H (2000). "Comparison of St John's wort and imipramine for treating depression: randomised controlled trial". BMJ. 321 (7260): 536–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7260.536. PMC 27467. PMID 10968813.

- ^ Schrader E (2000). "Equivalence of St John's wort extract (Ze 117) and fluoxetine: a randomized, controlled study in mild-moderate depression". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 15 (2): 61–8. doi:10.1097/00004850-200015020-00001. PMID 10759336.

- ^ Jensen AG, Hansen SH, Nielsen EO (2001). "Adhyperforin as a contributor to the effect of Hypericum perforatum L. in biochemical models of antidepressant activity". Life Sci. 68 (14): 1593–605. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(01)00946-8. PMID 11263672.

- ^ "St. John's wort". Natural Standard. Cambridge, MA. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Anzenbacher, Pavel; Zanger, Ulrich M., eds. (2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527630905. ISBN 978-3-527-63090-5.

- ^ Jensen AG, Hansen SH, Nielsen EO (2001). "Adhyperforin as a contributor to the effect of Hypericum perforatum L. in biochemical models of antidepressant activity". Life Sci. 68 (14): 1593–1605. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(01)00946-8. PMID 11263672.

- ^ a b Krusekopf S, Roots I (2005). "St. John's wort and its constituent hyperforin concordantly regulate expression of genes encoding enzymes involved in basic cellular pathways". Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 15 (11): 817–829. doi:10.1097/01.fpc.0000175597.60066.3d. PMID 16220113.

- ^ a b c Obach RS (2000). "Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes by constituents of St. John's Wort, an herbal preparation used in the treatment of depression" (PDF). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 294 (1): 88–95. PMID 10871299.

- ^ a b c d Kubin A, Wierrani F, Burner U, Alth G, Grünberger W (2005). "Hypericin--the facts about a controversial agent" (PDF). Curr. Pharm. Des. 11 (2): 233–253. doi:10.2174/1381612053382287. PMID 15638760.

- ^ Peebles KA, Baker RK, Kurz EU, Schneider BJ, Kroll DJ (2001). "Catalytic inhibition of human DNA topoisomerase IIalpha by hypericin, a naphthodianthrone from St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum)". Biochem. Pharmacol. 62 (8): 1059–1070. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00759-6. PMID 11597574.

- ^ Kerb R, Brockmöller J, Staffeldt B, Ploch M, Roots I (1996). "Single-dose and steady-state pharmacokinetics of hypericin and pseudohypericin" (PDF). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40 (9): 2087–2093. PMC 163478. PMID 8878586.

- ^ Meruelo D, Lavie G, Lavie D (1988). "Therapeutic agents with dramatic antiretroviral activity and little toxicity at effective doses: aromatic polycyclic diones hypericin and pseudohypericin" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (14): 5230–5234. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.14.5230. PMC 281723. PMID 2839837.

- ^ Lavie G, Valentine F, Levin B, Mazur Y, Gallo G, Lavie D, Weiner D, Meruelo D (1989). "Studies of the mechanisms of action of the antiretroviral agents hypericin and pseudohypericin" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 (15): 5963–5967. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.15.5963. PMC 297751. PMID 2548193.

- ^ Takahashi I, Nakanishi S, Kobayashi E, Nakano H, Suzuki K, Tamaoki T (1989). "Hypericin and pseudohypericin specifically inhibit protein kinase C: possible relation to their antiretroviral activity". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 165 (3): December 1989. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(89)92730-7. PMID 2558652.

- ^ von Moltke LL, Weemhoff JL, Bedir E, Khan IA, Harmatz JS, Goldman P, Greenblatt DJ (2004). "Inhibition of human cytochromes P450 by components of Ginkgo biloba". J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 56 (8): 1039–1044. doi:10.1211/0022357044021. PMID 15285849.

- ^ Lee JS, Lee MS, Oh WK, Sul JY (2009). "Fatty acid synthase inhibition by amentoflavone induces apoptosis and antiproliferation in human breast cancer cells" (PDF). Biol. Pharm. Bull. 32 (8): 1427–1432. doi:10.1248/bpb.32.1427. PMID 19652385.

- ^ Wilsky S, Sobotta K, Wiesener N, Pilas J, Althof N, Munder T, Wutzler P, Henke A (2012). "Inhibition of fatty acid synthase by amentoflavone reduces coxsackievirus B3 replication". Arch. Virol. 157 (2): 259–269. doi:10.1007/s00705-011-1164-z. PMID 22075919.

- ^ Lee JS, Sul JY, Park JB, Lee MS, Cha EY, Song IS, Kim JR, Chang ES (2013). "Fatty acid synthase inhibition by amentoflavone suppresses HER2/neu (erbB2) oncogene in SKBR3 human breast cancer cells". Phytother Res. 27 (5): 713–720. doi:10.1002/ptr.4778. PMID 22767439.

- ^ Katavic PL, Lamb K, Navarro H, Prisinzano TE (2007). "Flavonoids as opioid receptor ligands: identification and preliminary structure-activity relationships". J. Nat. Prod. 70 (8): 1278–82. doi:10.1021/np070194x. PMC 2265593. PMID 17685652.

- ^ Hanrahan JR, Chebib M, Davucheron NL, Hall BJ, Johnston GA (2003). "Semisynthetic preparation of amentoflavone: A negative modulator at GABA(A) receptors". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13 (14): 2281–4. doi:10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00434-7. PMID 12824018.

- ^ Viola H, Wasowski C, Levi de Stein M, Wolfman C, Silveira R, Dajas F, Medina JH, Paladini AC (1995). "Apigenin, a component of Matricaria recutita flowers, is a central benzodiazepine receptors-ligand with anxiolytic effects". Planta Med. 61 (3): 213–216. doi:10.1055/s-2006-958058. PMID 7617761.

- ^ Bao YY, Zhou SH, Fan J, Wang QY (2013). "Anticancer mechanism of apigenin and the implications of GLUT-1 expression in head and neck cancers". Future Oncol. 9 (9): 1353–1364. doi:10.2217/fon.13.84. PMID 23980682.

- ^ Lefort ÉC, Blay J (2013). "Apigenin and its impact on gastrointestinal cancers". Mol Nutr Food Res. 57 (1): 962–968. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201200424. PMID 23197449.

- ^ Crespy, V; Williamson, G. "A Review of the Health Effects of Green Tea Catechins in In Vivo Animal Models" (PDF). The Journal of Nutrition. 134 (12): 3431S – 3440S.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chacko SM, Thambi PT, Kuttan R, Nishigaki I (2010). "Beneficial effects of green tea: a literature review" (PDF). Chin Med. 5 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-5-13. PMC 2855614. PMID 20370896.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Korte G, Dreiseitel A, Schreier P, Oehme A, Locher S, Geiger S, Heilmann J, Sand PG (2010). "Tea catechins' affinity for human cannabinoid receptors". Phytomedicine. 17 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2009.10.001. PMID 19897346.

- ^ Song M, Hong M, Lee MY, Jee JG, Lee YM, Bae JS, Jeong TC, Lee S (2013). "Selective inhibition of the cytochrome P450 isoform by hyperoside and its potent inhibition of CYP2D6". Food Chem. Toxicol. 59: 549–553. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.055. PMID 23835282.

- ^ Li S, Zhang Z, Cain A, Wang B, Long M, Taylor J (2005). "Antifungal activity of camptothecin, trifolin, and hyperoside isolated from Camptotheca acuminata". J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 (1): 32–37. doi:10.1021/jf0484780. PMID 15631505.

- ^ Zeng KW, Wang XM, Ko H, Kwon HC, Cha JW, Yang HO (2011). "Hyperoside protects primary rat cortical neurons from neurotoxicity induced by amyloid β-protein via the PI3K/Akt/Bad/Bcl(XL)-regulated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 672 (1–3): 45–55. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.09.177. PMID 21978835.

- ^ Kim SJ, Um JY, Lee JY (2011). "Anti-inflammatory activity of hyperoside through the suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation in mouse peritoneal macrophages". Am. J. Chin. Med. 39 (1): 171–181. doi:10.1142/S0192415X11008737. PMID 21213407.

- ^ Haas JS, Stolz ED, Betti AH, Stein AC, Schripsema J, Poser GL, Rates SM (2011). "The anti-immobility effect of hyperoside on the forced swimming test in rats is mediated by the D2-like receptors activation" (PDF). Planta Med. 77 (4): 334–339. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250386. PMID 20945276.

- ^ Zheng M, Liu C, Pan F, Shi D, Zhang Y (2012). "Antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside isolated from Apocynum venetum leaves: possible cellular mechanisms". Phytomedicine. 19 (2): 145–149. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2011.06.029. PMID 21802268.

- ^ Pal D, Mitra AK (2006). "MDR- and CYP3A4-mediated drug-herbal interactions". Life Sci. 78 (18): 2131–2145. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.010. PMID 16442130.

- ^ Hämäläinen M, Nieminen R, Vuorela P, Heinonen M, Moilanen E (2007). "Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids: genistein, kaempferol, quercetin, and daidzein inhibit STAT-1 and NF-kappaB activations, whereas flavone, isorhamnetin, naringenin, and pelargonidin inhibit only NF-kappaB activation along with their inhibitory effect on iNOS expression and NO production in activated macrophages" (PDF). Mediators Inflamm. 2007: 45673. doi:10.1155/2007/45673. PMC 2220047. PMID 18274639.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Berger A, Venturelli S, Kallnischkies M, Böcker A, Busch C, Weiland T, Noor S, Leischner C, Weiss TS, Lauer UM, Bischoff SC, Bitzer M (2013). "Kaempferol, a new nutrition-derived pan-inhibitor of human histone deacetylases". J. Nutr. Biochem. 24 (6): 977–985. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.07.001. PMID 23159065.

- ^ a b Calderón-Montaño JM, Burgos-Morón E, Pérez-Guerrero C, López-Lázaro M (2011). "A review on the dietary flavonoid kaempferol". Mini Rev Med Chem. 11 (4): 298–344. doi:10.2174/138955711795305335. PMID 21428901.

- ^ Seelinger G, Merfort I, Schempp CM (2008). "Anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic activities of luteolin". Planta Med. 74 (14): 1667–1677. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1088314. PMID 18937165.

- ^ Lin Y, Shi R, Wang X, Shen HM (2008). "Luteolin, a flavonoid with potential for cancer prevention and therapy" (PDF). Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 8 (7): 634–646. doi:10.2174/156800908786241050. PMC 2615542. PMID 18991571.

- ^ Theoharides TC, Asadi S, Panagiotidou S (April–June 2012). "A case series of a luteolin formulation (NeuroProtek®) in children with autism spectrum disorders". Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 25 (2): 317–323. PMID 22697063.

- ^ Yu MC, Chen JH, Lai CY, Han CY, Ko WC (2010). "Luteolin, a non-selective competitive inhibitor of phosphodiesterases 1-5, displaced [3H]-rolipram from high-affinity rolipram binding sites and reversed xylazine/ketamine-induced anesthesia". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 627 (1–3): 269–275. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.031. PMID 19853596.

- ^ Chen C, Zhou J, Ji C (2010). "Quercetin: a potential drug to reverse multidrug resistance". Life Sci. 87 (11–12): 333–338. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2010.07.004. PMID 20637779.

- ^ a b Kelly, GS (June 2011). "Quercetin" (PDF). Alternative Medicine Review. 16 (2): 172–194. ISSN 1089-5159.

- ^ Ko WC, Shih CM, Lai YH, Chen JH, Huang HL (2004). "Inhibitory effects of flavonoids on phosphodiesterase isozymes from guinea pig and their structure-activity relationships". Biochem. Pharmacol. 68 (10): 2087–2094. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.030. PMID 15476679.

- ^ Chua LS (2013). "A review on plant-based rutin extraction methods and its pharmacological activities". J Ethnopharmacol. 150 (3): 805–817. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.10.036. PMID 24184193.

- ^ Jaikang, C; Niwatananun, K; Narongchai, P; Narongchai, S; Chaiyasut, C (August 2011). "Inhibitory effect of caffeic acid and its derivatives on human liver cytochrome P450 3A4 activity". Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 5 (15): 3530–3536.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hou, J; Fu, J; Zhang, ZM; Zhu, HL. "Biological activities and chemical modifications of caffeic acid derivatives". Fudan University Journal of Medical Sciences. 38 (6): 546–552. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1672-8467.2011.06.017.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhao Y, Wang J, Ballevre O, Luo H, Zhang W (2012). "Antihypertensive effects and mechanisms of chlorogenic acids". Hypertens. Res. 35 (4): 370–374. doi:10.1038/hr.2011.195. PMID 22072103.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ http://www.acdlabs.com/resources/freeware/chemsketch/ACDChemSketch

- ^ Lee MJ, Maliakal P, Chen L, Meng X, Bondoc FY, Prabhu S, Lambert G, Mohr S, Yang CS (2002). "Pharmacokinetics of tea catechins after ingestion of green tea and (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate by humans: formation of different metabolites and individual variability" (PDF). Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 11 (10 Pt 1): 1025–1032. PMID 12376503.

- ^ Walle T, Walle UK, Halushka PV (2001). "Carbon dioxide is the major metabolite of quercetin in humans" (PDF). J. Nutr. 131 (10): 2648–2652. PMID 11584085.

Further reading

- British Herbal Medicine Association Scientific Committee (1983). British Herbal Pharmacopoeia. West Yorkshire: British Herbal Medicine Association. ISBN 0-903032-07-4.

- Müller, Walter (2005). St. John's Wort and its Active Principles in Depression and Anxiety. Basel: Birkhäuser. doi:10.1007/b137619. ISBN 978-3-7643-6160-0.

External links

- Barrett S (2000). "St. John's Wort". Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- "St. John's wort: MedlinePlus Supplements". U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- Species Profile — St. Johnswort (Hypericum perforatum), National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library. Lists general information and resources for St John's wort.