Wolf's Lair

54°04′49″N 21°29′39″E / 54.0804°N 21.4941°E

| Wolf's Lair | |

|---|---|

Wolfsschanze | |

| Part of Führerhauptquartiere | |

| Forest Gierłoż, Rastenburg, Poland | |

Entrance to the Führer Bunker at the Wolfsschanze. | |

Location within present-day borders of the Wolf's Lair. | |

| Type | Blast-resistant camouflaged concrete bunkers |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Polish Government |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Destroyed (in ruins) |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1941 (completed on 21 June 1941) |

| Built by | Hochtief AG Organisation Todt |

| In use | Third Reich |

| Materials | 2 m (6 ft 7 in) steel-reinforced concrete |

| Demolished | 24–25 January 1945 |

| Events | 20 July Plot |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Adolf Hitler |

Wolf's Lair (Template:Lang-de) was Adolf Hitler's first Eastern Front military headquarter in World War II.[1] The complex, which would become one of several Führerhauptquartiere (Führer Headquarters) located in various parts of occupied Europe, was built for the start of Operation Barbarossa – the invasion of the Soviet Union – in 1941. It was constructed by Organisation Todt.[1]

The top secret, high security site was in the Masurian woods about 8 km (5.0 mi) from the small East Prussian town of Rastenburg (now Kętrzyn in Poland). Three security zones surrounded the central complex where the Führer's bunker was located. These were guarded by personnel from the SS Reichssicherheitsdienst and the Wehrmacht's armoured Führer Begleit Brigade. Despite the security, an assassination attempt against Hitler was made at Wolf's Lair on 20 July 1944.[1]

Hitler first arrived at the headquarters on 23 June 1941. In total, he spent more than 800 days at the Wolfsschanze during a 3+1⁄2-year period until his final departure on 20 November 1944.[1] In the summer of 1944, work began to enlarge and reinforce many of the Wolf's Lair original buildings. However, the work was never completed because of the rapid advance of the Red Army during the Baltic Offensive in autumn 1944. On 25 January 1945, the complex was blown up and abandoned 48 hours before the arrival of Soviet forces.[1]

Name

Wolfsschanze is derived from "Wolf", a self-adopted nickname of Hitler.[2] He began using the nickname in the early 1930s and it was often how he was addressed by those in his intimate circle. "Wolf" was used in several titles of Hitler's headquarters throughout occupied Europe, such as Wolfsschlucht I and II in Belgium and Werwolf in Ukraine.[3]

Although the standard translation in English is the "Wolf's Lair", Schanze in German translates as "sconce" or "fortification".

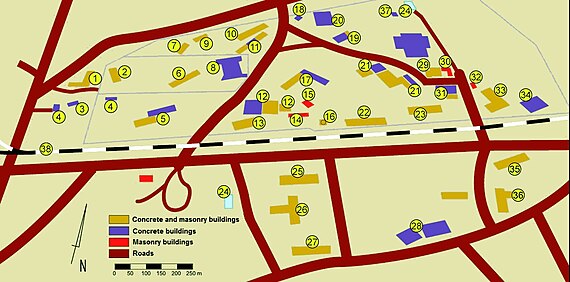

Layout

The decision to build the Wolf's Lair was made in the autumn of 1940. Built in the middle of a forest, it was located far from major roads and urban areas. The 6.5 km2 (2.5 sq mi) complex, which was completed by 21 June 1941, consisted of three concentric security zones.[4] About two thousand people lived and worked at the Wolf's Lair at its peak, among them twenty women;[4] some of whom were required to eat Hitler's food to test for poison.[5] The installations were served by a nearby airfield and railway lines. Buildings within the complex were camouflaged with bushes, grass and artificial trees planted on the flat roofs; netting was also erected between buildings and the surrounding forest so from the air, the installation looked like unbroken dense woodland.[4]

- Sperrkreis 1 (Security Zone 1) was located at the heart of the Wolf's Lair. Ringed by steel fencing and guarded by the Reichssicherheitsdienst (RSD), it contained the Führer Bunker and ten other camouflaged bunkers built from 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) thick steel-reinforced concrete. These shelters protected members of Hitler's inner circle such as Martin Bormann, Hermann Göring, Wilhelm Keitel and Alfred Jodl. Hitler's accommodation was on the northern side of Führer Bunker so as to avoid direct sunlight. Both Hitler's and Keitel's bunkers had additional rooms where military conferences could be held.[1]

- Sperrkreis 2 (Security Zone 2) surrounded the inner zone. This area housed the quarters of several Reich Ministers such as Fritz Todt, Albert Speer, and Joachim von Ribbentrop. It also housed the quarters of the personnel who worked in the Wolf's Lair and the military barracks for the RSD.

- Sperrkreis 3 (Security Zone 3) was the heavily fortified outer security area which surrounded the two inner zones. It was defended by land mines and the Führer Begleit Brigade (FBB), a special armoured security unit from Wehrmacht which manned guard houses, watchtowers and checkpoints.

A facility for Army headquarters was also located near the Wolf's lair complex.[1]

Although the RSD had overall responsibility for Hitler's personal security, external protection of the complex was provided by the FBB, which had become a regiment by July 1944. The FBB was equipped with tanks, anti-aircraft guns and other heavy weapons. Any approaching aircraft could be detected up to 100 kilometres (62 mi) from the Wolf's Lair. Additional troops were also stationed about 75 kilometres (47 mi) away.[4]

| 1. Office and barracks of Hitler's bodyguard 2. RSD command centre 3. Emergency generator 4. Bunker 5. Office of Otto Dietrich, Hitler's press secretary 6. Conference room, site 20 July 1944 assassination attempt 7. RSD command post 8. Guest bunker and air-raid shelter 9. RSD command post 10. Secretariat under Philipp Bouhler 11. Headquarters of Johann Rattenhuber, SS chief of Hitler's security department, and Post Office 12. Radio and telex buildings 13. Vehicle garages | 14. Railway siding for Hitler's Train 15. Cinema 16. Generator buildings 17. Quarters of Morell, Bodenschatz, Hewel, Voß, Wolff and Fegelein 18. Stores 19. Residence of Martin Bormann, Hitler's personal secretary 20. Bormann's personal air-raid shelter for himself and staff 21. Office of Hitler's adjutant and the Wehrmacht's personnel office 22. Military and staff mess II 23. Quarters of General Alfred Jodl, Chief of Operations of OKW 24. Firefighting pond 25. Office of the Foreign Ministry 26. Quarters of Fritz Todt, then after his death Albert Speer | 27. RSD command post 28. Air-raid shelter with Flak and MG units on the roof 29. Hitler's bunker and air-raid shelter 30. New tearoom 31. Residence of General Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, supreme commander of OKW 32. Old Teahouse 33. Residence of Reich Marshal Hermann Göring 34. Göring's personal air-raid shelter for himself and staff, with Flak and MG on the roof 35. Offices of the High Command of the Air Force 36. Offices of the High command of the Navy 37. Bunker with Flak 38. Ketrzyn railway line |

Reinforcements

Traudl Junge, one of Hitler's secretaries, recalled that in late 1943 or early 1944, Hitler spoke repeatedly of the possibility of a devastating bomber attack on the Wolfsschanze by the Western Allies. She quoted Hitler as saying, "They know exactly where we are, and sometime they’re going to destroy everything here with carefully aimed bombs. I expect them to attack any day." [6]

When Hitler’s entourage returned to the Wolfsschanze from an extended summer stay at the Berghof in July 1944, the previous small bunkers had been replaced by the Organisation Todt with "heavy, colossal structures" of reinforced concrete as defense against the feared air attack.[7] According to Armaments Minister Albert Speer, "some 36,000,000 marks were spent for bunkers in Rastenburg [Wolf's Lair]." [8] Hitler’s bunker had become the largest, "a positive fortress" containing "a maze of passages, rooms and halls." Junge wrote that, in the period between the 20 July assassination attempt and Hitler's final departure from the Wolfsschanze in November 1944, "We had air-raid warnings every day [...] but there was never more than a single aircraft circling over the forest, and no bombs were dropped. All the same, Hitler took the danger very seriously, and thought all these reconnaissance flights were in preparation for the big raid he was expecting."[9]

No air attack ever came. Whether the Western Allies knew of the Wolfsschanze's location and importance has never been revealed. For its part, the Soviet Union was unaware of both the location and scale of the complex until it was uncovered by their forces in their advance towards Germany in early 1945.[10]

Hitler's daily routine

When Hitler was in residence, he would begin the day by taking a walk alone with his dog around 9 or 10 am, and at 10:30 am would look at the mail which had been delivered by air or courier train.[4] A noon situation briefing, which frequently ran as long as two hours, would be convened in Keitel's and Jodl's bunker. This was followed by lunch at 2 pm in the dining hall. Hitler would invariably sit in the same seat between Jodl and Otto Dietrich, while opposite him sat Keitel, Martin Bormann and General Karl Bodenschatz, Goering's adjutant.[1]

After lunch, Hitler would deal with non-military matters for the remainder of the afternoon. Coffee was served around 5 pm, followed by a second military briefing by Jodl at 6 pm. Dinner, which could also last as long as two hours, began at 7:30 pm, after which films were shown in the cinema. Hitler would then retire to his private quarters where he would give monologues to his entourage, including the two female secretaries who had accompanied him to the Wolf's Lair.[11] Occasionally Hitler and his entourage listened to gramophone records of Beethoven symphonies, selections from Wagner or other operas, or German lieder.[1]

Notable visitors

- Antonescu, Ion (marshal) – Romania[12][13][14]

- Boris III of Bulgaria (tsar) – Bulgaria[15][16]

- Bose, Subhas Chandra (independence politician) – India[17]

- Bozhilov, Dobri (prime minister '43-44) – Bulgaria[18]

- Ciano, Galeazzo (minister of foreign affairs) – Italy[19][20]

- Csatay von Csatai, Lajos (general, ministry of war) – Hungary[21]

- Erden, Ali Fuat (general) – Turkey[22]

- Gailani, Rashid Ali al- (former prime minister) – Iraq[23]

- Gariboldi, Italo (general) – Italy[24]

- Graziani, Rodolfo (marshal) – Italy[25]

- Horthy, Miklós (regent) – Hungary[26]

- Jany, Vitéz Gusztáv (general) – Hungary[27]

- Kállay de Nagy-Kálló, Miklós (prime minister) – Hungary[28]

- Koburg, Kiril (prince of Bulgaria and Preslav, tsar successor) – Bulgaria[29]

- Kvaternik, Slavko (commander and minister of armed forces) – Croatia[30]

- Laval, Pierre (prime minister of Vichy regime) – France[31]

- Lukash, Konstantin/Константин Лукаш (general, chief of Staff of the Bulgarian Army) – Bulgaria[32]

- Luukkonen Fanni (army colonel, leader of the voluntary auxiliary organisation for women) – Finland[33]

- Mannerheim, Carl Gustaf (military leader and statesman) – Finland[34]

- Mayalde, Jose Finat y Escrivá de Romaní (Conde de Mayalde, ambassador to Third Reich) – Spain[35]

- Michov, Nikoła Michaiłov/Никола Михайлов Михов (general, minister of war) – Bulgaria[36]

- Moscardó Ituarte, José (general) – Spain[37]

- Mussolini, Benito (il Duce) – Italy[38][39][40][41]

- Nedić, Milan (general, prime minister) – Serbia[42]

- Öhquist, Harald (lieutenant general) – Finland[43]

- Ōshima, Hiroshi (general, ambassador to Third Reich) – Japan[44][45][46]

- Ante Pavelic (Poglavnik, Ustasha leader of Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina) – Croatia[43]

- Tiso, Jozef (Roman Catholic priest, President) – Slovakia[47]

- Tovar de Lemos, Pedro (2º Conde de Tovar, diplomat) – Spain[48]

- Toydemir, Cemil Cahit – (general) - Turkey[49]

Assassination attempt

In July 1944, an attempt was made to kill Hitler at the Wolf's Lair. The assassination, which became known as the 20 July plot, was organized by a group of acting and retired Heer Army officers and some civilians who wanted to remove Hitler in order to establish a new governance in Germany. After several failed attempts to kill Hitler, the Wolf's Lair – despite its security – was chosen as a viable location. Staff officer Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg would carry a briefcase bomb into a daily conference meeting and place it just a few feet away from Hitler.

However due to the reconstruction of the Führer Bunker in the summer of 1944, the location was changed to a building known as the Lager barrack on the day of the strategy meeting. This alternate venue along with several other factors, such as Hitler unexpectedly calling the meeting earlier than anticipated, meant Stauffenberg's attempt would prove unsuccessful. At 12:43 pm, when the bomb exploded, the interior of the building was devastated but Hitler was only slightly injured. Four other people present died from their wounds a few days later.

Before the bomb detonated, Stauffenberg and his adjutant, Lieutenant Werner von Haeften had already begun to leave the Wolfsschanze in order to return to Berlin. Their escape involved passing through various security zones that controlled all access around the site. After a short delay at the RSD guard post just outside Sperrkreis 1, they were allowed to leave by vehicle. The two officers were then driven down the southern exit road towards the military airstrip near Rastenburg (at 54°2′36″N 21°25′57″E / 54.04333°N 21.43250°E). However by the time they reached the guard house at the perimeter of Sperrkreis 2, the alarm had been sounded. According to the official RHSA report, "at first the guard refused passage until Stauffenberg persuaded him to contact the adjutant to the compound commander who then finally authorized clearance". It was between here and the final checkpoint of Sperrkreis 3 that Haeften tossed another briefcase from the car containing an unused second bomb. On reaching the outer limit of the Wolfsschanze security zones, the two men were allowed to catch their plane back to army general headquarters in Berlin.

The attempted assassination of Hitler at the Wolf Lair was part of Operation Valkyrie, a covert plan to take control and suppress any revolt in the German Reich following Hitler's death. However once news arrived from the Wolf's Lair that the Führer was still alive, the plan failed as troops loyal to the Nazi regime quickly re-established control of key government buildings. Von Stauffenberg, his adjutant Werner von Haeften and several co-conspirators were arrested and shot the same evening.

On 20 August 1944, Hitler personally presented survivors of the bomb blast in the Wolf's Lair with a gold "20 July 1944 Wound Badge". Next-of-kin of those killed in the bomb blast were also given this award.

Demise

In October 1944 the Red Army reached the borders of East Prussia during the Baltic Offensive. Hitler departed from the Wolf's Lair for the final time on 20 November when the Soviet advance reached Angerburg (now Węgorzewo), only 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) away. Two days later the order was given to destroy the complex. However the actual demolition did not take place until the night of 24–25 January 1945, ten days after the start of the Red Army's Vistula–Oder Offensive. Despite the use of tons of explosives - one bunker required an estimated 8,000 kg (18,000 lb) of TNT - most of the buildings were only partially destroyed due their immense size and reinforced structures.

The Red Army captured the abandoned remains of the Wolfsschanze on 27 January without firing a shot: the same day Auschwitz was liberated. It took until 1955 to clear over 54,000 land mines which surrounded the installation.[4]

Historical site

Although the area was cleared of abandoned ordnance such as land mines following the war, the entire site was left to decay by Poland's Communist government. However since the Fall of Communism in the early 1990s, the Wolf's Lair has been developed as a tourist attraction. Visitors can make day trips from Warsaw or Gdańsk.[50] Hotel and eateries have grown up near the site.[51] Periodically plans have been proposed to restore the area, including the installation of historical exhibits.[52]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kershaw 2000[page needed]

- ^ Antony Beevor (2001). Stalingrad. London: Penguin Books. p. 97. ISBN 0-14-100131-3.

As an alternative to Wolfsschanze at Rastenburg, it was code-named Werwolf. (The word Wolf, an old German version of Adolf, clearly gave the Führer an atavistic thrill.)

- ^ John Toland (1978). Adolf Hitler. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 978. ISBN 0-345-27385-0.

Hitler moved his headquarters deep into the Ukraine […] a few miles northeast of Vinnitsa. Christened Werwolf by himself, it was an uncamouflaged collection of wooden huts located in a dreary area.

- ^ a b c d e f Wolf's Lair website

- ^ Claire Cohen (18 September 2014). "Last surviving female food taster, 96: 'I never saw Hitler, but I had to risk my life for him every day'". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Junge, Traudl (2003). Until the Final Hour. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 116.

- ^ Junge, Traudl. Until the Final Hour. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003, p. 126.

- ^ Speer, A: Inside the Third Reich, p.217

- ^ Junge, Traudl. Until the Final Hour. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Berlin: The Fateful Siege, Antony Beevor

- ^ Eva Braun never came to the Wolf's Lair.

- ^ 11.02.1942, : pict., publisher (pl): National Digital Archives, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 10-13.01.1943, : pict., publisher (pl): National Digital Archives, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 05/06.08.1944, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 24.03.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 14/15.08.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 29.05.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 05.11.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 25.10.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 18.12.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 17.08.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 28.10.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 15.07.1942, : pict., publisher (pl): National Digital Archives, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 07.05.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ ??.10.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 08.09.1941, : pict., publisher (pl): National Digital Archives, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 16.05.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 06.06.1942, : pict., publisher (pl): National Digital Archives, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 18/19.10.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 21.07.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 19.12.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 08.12.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 26.05.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 27/28.06.1942, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 11.09.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 08.01.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 07.12.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 25.08.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 28.08.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 14.09.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 20.07.1944, : pict., publisher (pl): National Digital Archives, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 18.09.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ a b 30.07.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 15.07.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ end of July 1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ 04.09.1944, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 20.10.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 11.09.1941, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ 06.07.1943, : pict., publisher (de): Prussian Heritage Image Archive, retrieved 20 September 2013

{{citation}}:|last=has numeric name (help) - ^ Wolf’s Lair trips from Warsaw

- ^ Wolf's Lair amenities

- ^ Restoring the Walls and the History at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair

References

- Sources

- Junge, Traudl, "Bis Zur Letzten Stunde: Hitlers Sekretärin erzählt ihr Leben", München: Claassen, 2002, pp. 131, 141, 162.

- Junge, Traudl, "Until the Final Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary", London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 2003, pp. 116, 126, 145.

- Junge, Traudl, "Voices from the Bunker", New York: G.P.Puttnam's sons, 1989.

- Kershaw, Ian (2000). Hitler, 1936–45. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-04994-7.

- Speer, Albert, "Inside the Third Reich", New York and Toronto: Macmillan, 1970, p. 217.

- Documentary

- Ruins of the Reich DVD R.J. Adams (history and ruins of Wolfsschanze)