Lampris guttatus

| Lampris guttatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Opah | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | L. guttatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lampris guttatus | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

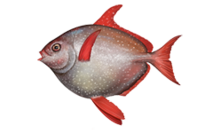

Lampris guttatus, commonly known as the opah, cravo, moonfish, kingfish, and Jerusalem haddock, is a large, colorful, deep-bodied pelagic lampriform fish belonging to the family Lampridae, which comprises the genus Lampris, with two extant species.

It is a pelagic fish with a worldwide distribution. While it is common to locations such as Hawaii[2] and west Africa, it remains uncommon in others, including the Mediterranean.[3] In the places where L. guttatus is prevalent, it is not a target of fishing, though it does represent an important commercial component of bycatch. It is common in restaurants in Hawaii. In Hawaiian longline fisheries, it is generally caught on deep sets targeting big-eye tuna. In 2005, the fish caught numbered 13,332. In areas where the fish is uncommon, such as the Mediterranean, its prevalence is increasing. Some researchers believe this a result of climate change.[3] Much is still unknown about the distribution, interactions, life histories, and preferred habitats of this fish and other medium to large-sized pelagic fishes.[4]

In May 2015, L. guttatus was shown to maintain its entire body core above ambient temperature, becoming the first known fish with this trait ('whole-body endothermy').[5][6] It can consistently keep its body core approximately 5 °C (9.0 °F) warmer than its environment.[7]

Etymology

Danish zoologist Morten Thrane Brünnich described the species in 1788. The genus name Lampris is derived from the Ancient Greek word lampros, meaning "brilliant" or "clear", while the Latin species name guttatus means "spotted" and refers to the spotted body of this fish.[1]

Description

Lampris guttatus is a large discoid and deeply keeled fish with an attractive form and a conspicuous coloration. They can reach a maximum length of 2 m (6.6 ft) and a maximum weight of 270 kg (600 lb). The body is a deep steely blue grading to rosy on the belly, with white spots in irregular rows covering the flanks. Both the median and paired fins are a bright vermillion. Jaws are vermillion, too. The large eyes stand out as well, ringed with golden yellow. The body is covered in minute cycloid scales and its silvery, iridescent guanine coating is easily abraded.

They have long falcated pectoral fins inserted (more or less) horizontally. The caudal fins are broadly lunated, forked, and emarginated. Pelvic fins are similar but a little longer than pectoral fins, with about 14–17 rays. The anterior portion of a dorsal fin (with about 50–55 rays) is greatly elongated, also in a falcate profile similar to the pelvic fins. The anal fin (34–41 rays) is about as high and as long as the shorter portion of the dorsal fin, and both fins have corresponding grooves into which they can be depressed. The snout is pointed and the mouth small, toothless, and terminal. The lateral line forms a high arch over the pectoral fins before sweeping down to the caudal peduncle.

Endothermy

In May 2015, L. guttatus was shown to maintain its entire body core above ambient temperature, becoming the first known fish with this trait ('whole-body endothermy'). The fish generates heat as well as propulsion with continuous movements of its pectoral fins (the musculature of which is insulated by a one-cm-thick layer of fat), and the vasculature of its gill tissue is structured to conserve heat by a process of countercurrent heat exchange.[5][6] It can consistently keep its body core approximately 5 °C warmer than its environment.[7] Previously, L. guttatus was known to exhibit cranial endothermy, generating and maintaining metabolic heat in the cranial and optic regions at 2 °C warmer than the rest of the body.[8] This ability is important for maintaining brain and eye function during the wide range of temperatures it experiences with its vertical movements.[9]

Most fish are completely cold-blooded. Some, such as tuna, have developed localized warm-blooded traits which only have selected muscles that are kept at a steady temperature. The salmon shark also has the ability to regulate its blood temperature, allowing it to function in the frigid North Pacific waters, but is not completely warm-blooded.[5][7]

Distribution and habitat

Lampris guttatus has a worldwide distribution, from the Grand Banks to Argentina in the Western Atlantic, from Norway and Greenland to Senegal and south to Angola in the Eastern Atlantic (also in the Mediterranean), from the Gulf of Alaska to southern California in the Eastern Pacific, in temperate waters of the Indian Ocean, and rare forays into the Southern Ocean.[1]

This species is presumed to live out its entire life in the open ocean, at mesopelagic depths of 50–500 m (160–1600 ft), with possible forays into the bathypelagic zone. Typically, it is found within water at 8 to 22 °C.[2] To better understand the depths L. guttatus inhabited in the tropical and temperate ocean waters, a study was performed, tagging them in the central North Pacific. Their location was found to be related to a temporal scale, inhabiting depths of 50–100 m during the night and 100–400 m during the day. The depths of the vertical habitat varied with local oceanogeographic conditions, though the patterns of deeper depths during the day is universal to the species.[4]

The endothermy of Lampris guttatus gives them a major advantage at the depths where they live. Since they are relatively warm-blooded at those depths compared to the water around them, they can move more quickly to hunt prey. Most predators at such low depths do not have the energy to be able to move much and therefore must sit and wait for prey to pass them.[5]

Behavior

The life history and development of L. guttatus still remains rather uncertain.[10] They are apparently solitary, but are known to school with tuna and other scombrids. They propel themselves by a lift-based mode of swimming, that is, by flapping their pectoral fins. This, together with their forked caudal fins and depressible median fins, indicates they swim at constantly high speeds. Squid and krill make up the bulk of their diet; small fish are also taken.

They probably spawn in the spring.[1] Their planktonic larvae lack of dorsal and pelvic fin ornamentation. The slender hatchlings later undergo a marked and rapid transformation from a slender to deep-bodied form; this transformation is complete by 10.6 mm standard length.

Like many other large pelagic visual predators, such as swordfish and big-eye tuna, it exhibits vertical behavior. Its speeds have found to be more than 25 cm/s, and on one occasion one was witnessed to have a burst of speed of 4 m/s.[2]

Based on those caught off the Hawaiian coast, the diet of L. guttatus appears to be a squid-based. Those caught along the Patagonian Shelf also showed a narrow range of prey items, the most common of which was the deepwater onychotenhid squid (Moroteuthis ingens).[2]

References

- ^ a b c d Lampris guttatus (Brünnich, 1788). Fish Base

- ^ a b c d Polovina, Jeffrey J.; Hawn, Donald; Abecassis, Melanie (2008). "Vertical movement and habitat of opah (Lampris guttatus) in the central North Pacific recorded with pop-up archival tags". Marine Biology. 153 (3): 257–267. doi:10.1007/s00227-007-0801-2.

- ^ a b Francour, Patrice; Cottalorda, Jean-Michel; Aubert, Maurice; Bava, Simone; Colombey, Marine; Gilles, Pierre; Kara, Hichem; Lelong, Patrick; Mangialajo, Luisa; Miniconi, Roger; Quignard, Jean-Pierre (2010). "Recent Occurrences of Opah, Lampris guttatus (Actinopterygii, Lampriformes, Lampridae), in the Western Mediterranean Sea". Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria. 40 (1): 91–98. doi:10.3750/AIP2010.40.1.15.

- ^ a b Richardson, David E.; Llopiz, Joel K.; Guigand, Cedric M.; Cowen, Robert K. (2010). "Larval assemblages of large and medium-sized pelagic species in the Straits of Florida". Progress in Oceanography. 86 (1–2): 8–20. Bibcode:2010PrOce..86....8R. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2010.04.005.

- ^ a b c d Wegner, N. C.; Snodgrass, O. E.; Dewar, H.; Hyde, J. R. (15 May 2015). "Whole-body endothermy in a mesopelagic fish, the opah, Lampris guttatus". Science. 348 (6236): 786–789. doi:10.1126/science.aaa8902.

- ^ a b Warm Blood Makes Opah an Agile Predator. Fisheries Resources Division of the Southwest Fisheries Science Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2015. "New research by NOAA Fisheries has revealed the opah, or moonfish, as the first fully warm-blooded fish that circulates heated blood throughout its body..."

- ^ a b c Yong, Ed. "Meet the Comical Opah, the Only Truly Warm-Blooded Fish". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Bray, Dianne. "Opah, Lampris guttatus". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Runcie, R.; Dewar, H; Hawn, D. R.; Frank, L. R.; Dickson, K. A. (2009). "Evidence for cranial endothermy in the opah (Lampris guttatus)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 212 (4): 461–470. doi:10.1242/jeb.022814. PMC 2726851. PMID 19181893.

- ^ Oelschläger, Helmut A. (1976). "Morphologisch-funktionelle Untersuchungen am Geruchsorgan von Lampris guttatus (Brünnich 1788) (Teleostei: Allotriognathi)". Zoomorphology (in German). 85 (2): 89–110. doi:10.1007/BF00995406.

Further reading

- Parin, N. V.; Kukuyev, Y. I. (1983). "Establishment of validity of Lampris immaculata Gilchrist and the geographical distribution of Lampridae". Journal of Ichthyology. 23 (1): 1–12.