Bilbao

Bilbao

Bilbo Template:Eu icon | |

|---|---|

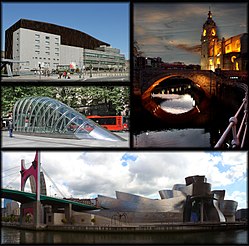

Clockwise from top: Panorama from mount Artxanda, Church of San Antón, Bilbao Guggenheim Museum, a fosterito, and the Euskalduna Palace | |

| Nickname: "The Hole" (Template:Lang-es) | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous community | |

| Province | Biscay |

| Comarca | Greater Bilbao |

| Founded | 15 June 1300 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Ibon Areso (PNV) |

| Area | |

| 41.50 km2 (16.02 sq mi) | |

| • Urban | 18.22 km2 (7.03 sq mi) |

| • Rural | 23.30 km2 (9.00 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 19 m (62 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 689 m (2,260 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2014)[1] | |

| 348,574 | |

| • Density | 8,400/km2 (22,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 950,155 |

| Demonym(s) | Template:Lang-en Template:Lang-eu Template:Lang-es |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 48001 – 48015 |

| Dialing code | +34 94 |

| Official language(s) | Basque Spanish |

| Website | Official website |

Bilbao (/bɪlˈbaʊˌ -ˈbɑːoʊ/,[2] Spanish pronunciation: [bil.ˈβa.o]; Template:Lang-eu, pronounced [bilβo]) or Bilbo is a municipality and city in Spain, the capital of the province of Biscay in the autonomous community of the Basque Country. It is the largest municipality of the Basque Country and the tenth largest in Spain, with a population of 353,187 in 2010.[3] The Bilbao metropolitan area has roughly 1 million inhabitants,[4][5][6] one of the most populous metropolitan areas in northern Spain, of which (pop. 875,552)[7] accounts for the comarca of Greater Bilbao, making it the fifth-largest urban area in Spain.

Bilbao is situated in the north-central part of Spain, some 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) south of the Bay of Biscay, where the estuary of Bilbao is formed. Its main urban core is surrounded by two small mountain ranges with an average elevation of 400 metres (1,300 ft).[8]

The borough of Bilbao was founded in the early 14th century by sovereign and semi sovereign families of Bizkaia such as the Bilbao la Vieja, and Diego López V de Haro, head of the powerful Haro family. Bilbao originated as the commercial hub of the Basque Country cultivated by the House de Sarachaga, who historically hold the sovereign fief of Bilbao as successors of The House of Haro.Through their guidance and in cooperation with local magnate families and the government; Bilbao enjoyed significant importance in the Green Spain. This was due to its port activity based on the export of iron extracted from the Biscayan quarries. Throughout the nineteenth century and beginnings of the twentieth, Bilbao experienced heavy industrialisation which made it the centre of the second-most industrialised region of Spain, behind Barcelona.[9][10] This was joined by an extraordinary population explosion that prompted the annexation of several adjacent municipalities. Nowadays, Bilbao is a vigorous service city that is experiencing an ongoing social, economic, and aesthetic revitalisation process, started by the iconic Bilbao Guggenheim Museum,[9][11][12][13] and continued by infrastructure investments, such as the airport terminal, the rapid transit system, the tram line, the Alhóndiga, and the currently under development Abandoibarra and Zorrozaurre renewal projects.[14]

Etymology

The official name of the town is Bilbao, as known in most languages of the world. Euskaltzaindia, the official regulatory institution of the Basque language, agreed that between the two possible names existing in Basque, Bilbao and Bilbo, that the historical name in Basque is Bilbo, while keeping the officialty of the first one.[15] Although the term Bilbo does not appear on old documents, in the play The Merry Wives of Windsor by William Shakespeare, there is a reference of swords presumably made of Biscayan iron to which he calls "bilboes", which might suggest that it is a word used since at least the sixteenth century.[16][17][18][19]

There is no consensus among historians about the origin of the name. The generally accepted accounts state that prior to the 12th century the independent rulers of the territory, named Senores de Zubialdea, were also known as Senores de Bilbao la Vieja. The symbol of their patrimony is the tower and church used in the shield of Bilbao to this day.[20] This patrimony was fully inherited by the de Sarachaga. Others possible origins were stated by the engineer Evaristo de Churruca. He said that was a Basque custom to name a place after its location, for Bilbao this would be the result of the union of the Basque words for river and cove: Bil-Ibaia-Bao.[21] Also, the historian José Tussel Gómez argues that it is just a natural evolution of the Spanish words bello vado, beautiful river crossing.[22] On the other hand, the writer Esteban Calle Iturrino said that the name derives from the two previous settlements that existed on both banks of the estuary, more than from the estuary by itself. The first one, where the current Casco Viejo is located, would be called billa, which means stacking in Basque, after the configuration of the buildings. The second one, located on the left bank, where now Bilbao La Vieja is located, would be called vaho, Spanish for mist or steam. From the union of these two, the name Bilbao would come out,[21] that previously was also written as Bilvao and Biluao, as documented in its municipal charter and its following transcriptions.[23]

Symbology

The titles, the flag and the coat of arms are Bilbao's traditional symbols and belong to its historic patrimony, being used in formal acts, for the identification and decoration of specific places or for the validation of documents.

- Titles

Bilbao holds the historic category of borough (villa), with the titles of «Very noble and very loyal and unbeaten» («Muy Noble y Muy Leal e Invicta»). It was the Catholic Monarchs who awarded on the 20th of September of 1475 the title «Noble borough» («Noble Villa»). Philip III of Spain, via a letter in 1603 awarded the borough the titles of «Very noble and very loyal».[24] After the Siege of Bilbao (1836), during the First Carlist War, the 25 of December 1836, the title of «Unbeaten» was added.[25]

History

Remains of an ancient settlement were found on the top of Mount Malmasín, dated around the 3rd or 2nd century BC.[26][27] Burial sites were also found on Mounts Avril and Artxanda, dated 6,000 years old. Some authors identify the old settlement of Bilbao as Amanun Portus, cited by Pliny the Elder, or with Flaviobriga, by Ptolemy.[27] Ancient walls, which date around the 11th century, have been discovered below the Church of San Antón.[27]

Bilbao was one of the first towns that was founded in the fourteenth century, during a period in which approximately 70% of the Biscayan municipalities were developed, among them Portugalete in 1323, Ondarroa in 1327, Lekeitio in 1335, and Mungia and Larrabetzu in 1376.[28] The then lord of Biscay, Diego López V of Haro, founded Bilbao through a municipal charter dated in Valladolid on 15 June 1300 and confirmed by King Ferdinand IV of Castile in Burgos, on 4 January 1301. Diego López established the new town on the right bank of the Nervión river, on grounds of the elizate of Begoña and granted it the fuero of Logroño, a compilation of rights and privileges that would prove fundamental to its later development.[29]

On 21 June 1511, Queen Joanna of Castile ordered the creation of the Consulate of Bilbao. This would become the most influential institution of the borough for centuries, and would claim jurisdiction over the estuary, improving its infrastructure. Under the Consulate's control, the port of Bilbao became one of the most important of Spain.[30] The first printing-press was brought to the town in 1577. Here in 1596, the first book in Basque was edited, entitled Doctrina Christiana en Romance y Bascuence by Dr. Betolaza.[31]

In 1602 Bilbao was made the capital of Biscay, a title previously held by Bermeo.[32] The following centuries saw a constant increase of the town's wealth, especially after the discovery of extensive iron resources in the surrounding mountains. At the end of the 17th century, Bilbao overcame the economical crises that affected Spain, thanks to the iron ore and its commerce with England and the Netherlands. During the 18th century, it continued to grow and almost exhausted its small space.

The Basque Country was one of the main sites of battles of the Carlist Wars, and the Carlists very much wanted to conquer the city, a liberal and economic bastion.[33] Bilbao was besieged three times between 1835 and 1874, but all proved unsuccessful. One of the main battles of this time was the Battle of Luchana in 1836, when Liberal general Baldomero Espartero defeated the Carlists, freeing the borough.[34]

Despite the warfare, Bilbao prospered during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when it rose as the economic centre of the Basque Country. During this time, the first railway was built (in 1857), the Bank of Bilbao was founded (which later would become the BBVA), and the Bilbao Stock Exchange was created. Many industries flourished, such as Altos Hornos de Vizcaya in 1902. The borough grew in area with the Abando ensanche and was modernized with new avenues and walkways, as well as with new modern buildings such as the City Hall, the Basurto Hospital and the Arriaga Theatre.[35] The population increased dramatically, going from 11,000 in 1880 to 80,000 in 1900. Social movements also occurred, specially the Basque nationalism under Sabino Arana.[36]

The Spanish Civil War started in Bilbao with small uprisings suppressed by the Republican forces. On 31 August 1936, the city suffered the first bombing. On the next month, further bombings by German planes occurred, in coordination with Franco's forces.[37] In May 1937, the Nationalist army besieged the town. The battle lasted until 19 June of that year, when Lieutenant Colonel Putz was ordered to destroy all bridges over the estuary, and the troops of the 5th Brigade took the borough from the mountains Malmasin, Pagasarri, and Arnotegi.[38]

With the war over, Bilbao returned to its industrial development, accompanied by a steady population growth. In the 1940s, the city was rebuilt, starting with the bridges. In 1948, the first commercial flight took off from the local airport.[39] Over the next decade, there was a revival of the iron industry. The demand for housing outstripped supply, and workers built slums on the hillsides.[40] In this chaotic environment, on 31 July 1959, the terrorist organization ETA was born in Bilbao, as a faction of the PNV.[40]

After the fall of Francoist Spain and the establishment of a constitutional monarchy, in a process known in Spain as the transition, Bilbao could hold democratic elections again. Against what happened in the republics, this time Basque nationalists rose to power.[41] With the approval of the Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country in 1979, Vitoria-Gasteiz was elected the seat of the government and therefore the de facto capital of the Basque Autonomous Community, despite Bilbao being larger and more powerful economically. In the 1980s, several factors such as terrorism, labor demands, and the arrival of cheap labor force from the abroad, led to a devastating industrial crisis.[40]

Since the mid-1990s, Bilbao has been in a process of deindustrialization and transition to a service town, supported by investment in infrastructure and urban renewal, that started with the opening of the Bilbao Guggenheim Museum (the so-called Guggenheim effect),[13] and continued with the Euskalduna Conference Centre and Concert Hall, Santiago Calatrava's Zubizuri, the metro network by Norman Foster, the tram, the Iberdrola Tower and the Zorrozaurre development plan, among others. Many officially supported associations, as Bilbao Metrópoli-30 and Bilbao Ría 2000 were created to monitor these projects.[42][43]

Geography

The municipality of Bilbao is located on the northern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, about 19 kilometres (12 mi) from the Bay of Biscay.[44] It covers an area of 40.65 square kilometres (15.70 sq mi), of which 17.35 square kilometres (6.70 sq mi) are urban, and the remaining 23.30 square kilometres (9.00 sq mi) consist of the surrounding mounts.[45] The official average altitude is 19 metres (62 ft), although there are measurements between 6 metres (20 ft) and 32 metres (105 ft).[46] It is also the core of the comarca of Greater Bilbao. It is surrounded by the municipalities of Derio, Etxebarri, Galdakao, Loiu, Sondika, and Zamudio to the north; Arrigorriaga and Basauri to the west; Alonsotegi to the south; and Barakaldo and Erandio to the east.

Geography

Bilbao is located on the Basque threshold, the range between the larger Cantabrian Mountains and the Pyrenees.[47] The composition of the soil is predominated by mesozoic materials (limestone, sandstone, and marl) sedimented over a primitive paleozoic base.[47] The province relief is dominated by NW-SE and WNW-ESE oriented folds. The main fold is the anticline of Bilbao, that runs from the municipality of Elorrio to Galdames.[47] Inside Bilbao there are two secondary folds, one in the northeast, composed by mounts Artxanda, Avril, Banderas, Pikota, San Bernabé, and Cabras; and other in the south, composed by mounts Kobetas, Restaleku, Pagasarri and Arraiz. The highest point in the municipality is mount Ganeta, of 689 metres (2,260 ft), followed by mount Pagasarri, of 673 metres (2,208 ft), both on the border with Alonsotegi.[48]

Hydrology

The main river system of Bilbao is also the hydrological artery of Biscay. The rivers Nervión and Ibaizabal converge in Basauri and form an estuary named "estuary of Bilbao", "of the Nervión", "of the Ibaizabal", or "of the Nervión-Ibaizabal".[49] This estuary runs for 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) and with a low flow (with an average of 25 m3 (883 cu ft) per second).[50] Its main tributary is the river Cadagua, that sources in the Mena valley and has a basin of 642 square kilometres (248 sq mi), which mostly lies in the neighboring province of Burgos.[51] This river is also the natural border between Bilbao and Barakaldo.

The river suffered from human intervention many times, as seen in the dredging of its bottom, the building of docks on both banks and especially in the Deusto canal, an artificial waterway dug between 1950 and 1968 in the district of Deusto as a lateral canal, with the aim to facilitate navigation, sparing ships from the natural curves of the estuary.[52] The project was stopped with 400 metres (1,300 ft) left to complete, and it was decided to leave it as a dock.[53] However, in 2007, a plan was approved to continue the canal and form the island of Zorrozaurre.[54] Said human intervention also brought negative results in the quality of the water, and after decades of toxic waste dumping, caused a situation of anoxia (lack of oxygen), which almost eliminated the entire fauna and flora.[50] However, in recent years this situation is being reversed, thanks to dumping clearance and natural regeneration.[55] now it is possible to observe algae, tonguefishes, crabs, and seabirds,[56] as well as occasional bathers in the summer months.[57]

The estuary also works as a natural border for several neighbourhoods and districts within the borough. Since entering the municipality, from the west, it divides the districts of Begoña and Ibaiondo, then Abando and Uribarri and lastly Deusto and Basurto-Zorroza.

Climate

The proximity to the Bay of Biscay gives Bilbao an oceanic climate (Cfb), with precipitation occurring throughout the year, without a well-defined dry summer season. This precipitation is abundant, and given the latitude and atmospheric dynamics, rainy days represent 45% and cloudy days 40% of the annual total.[58] The most rainy season is between October and April, November being the wettest. Snow is not frequent in Bilbao, while it is possible to see snow on the top of the surrounding mountains. Sleet is more frequent, about 10 days per year, mainly in the winter months.[59]

The aforementioned proximity to the ocean also makes that the two most defined seasons (summer and winter) remain mild, with low intensity thermal oscillations. Average maximum temperatures varies between 25 and 26 °C (77.0 and 78.8 °F) in the summer months, while the average minimum in winter is between 6 and 7 °C (42.8 and 44.6 °F).

Extreme record observations in Bilbao are 42.2 °C (108.0 °F) maximum (on 13 August 2003) and −8.6 °C (16.5 °F) minimum (on 3 February 1963). The maximum precipitation in a day was 225.6 mm (9 in) in 26 August 1983 when severe flooding was originated by the Nervión river.[60]

| Climate data for Bilbao airport: 1981-2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.5 (52.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 120 (4.7) |

86 (3.4) |

90 (3.5) |

107 (4.2) |

78 (3.1) |

60 (2.4) |

51 (2.0) |

77 (3.0) |

73 (2.9) |

111 (4.4) |

147 (5.8) |

122 (4.8) |

1,134 (44.6) |

| Average precipitation days | 13 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 11 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 124 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 85 | 97 | 132 | 138 | 169 | 181 | 186 | 179 | 160 | 127 | 88 | 78 | 1,610 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología,[61] Aena[62] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 83,306 | — |

| 1910 | 93,536 | +12.3% |

| 1920 | 112,819 | +20.6% |

| 1930 | 161,987 | +43.6% |

| 1940 | 195,186 | +20.5% |

| 1950 | 229,334 | +17.5% |

| 1960 | 297,272 | +29.6% |

| 1970 | 410,490 | +38.1% |

| 1980 | 433,030 | +5.5% |

| 1990 | 372,054 | −14.1% |

| 2000 | 354,271 | −4.8% |

| 2010 | 353,187 | −0.3% |

| 2013 | 349,356 | −1.1% |

The local Register office shows a total resident population for Bilbao of 349,356 in 2013[update].

The first credible data about Bilbao population are post-1550.[63] It is known that in 1530, Biscay had approximately 65,000 inhabitants, a number that could have been reduced by plagues that struck the city in 1517, 1530, 1564–68, and 1597–1601, the last one being specially devastating.[63] This trend in adverse situations for population growth was maintained until the nineteenth century. Since then, Bilbao experienced an exponential population growth thanks to the industrialisation of the area. After a peak of 433,115 inhabitants in 1982, the municipalities of the Txorierri valley were removed from Bilbao, with the corresponding loss of their population.[64]

Of the 355,731 people residing in Bilbao in 2009, only 114,220 (32.1%) were born inside the municipality. Of the remainder, 114,908 were born in other Biscayan towns, while 9,545 were born in the other two Basque provinces; 85,789 came from the rest of Spain (mainly Castile-León and Galicia), and 33,537 were foreigners.[65] There are 127 different nationalities registered in Bilbao, although 60 of them contain fewer than 10 people.[66] The largest foreign communities are the Bolivian and the Colombian, with 4,879 and 3,730 respectively. Other nationalities with more than 1,000 inhabitants are Romanian (2,248), Moroccan (2,058), Ecuadorian (1,832), Chinese (1,390), Brazilian (1,273) and Paraguayan, with 1,204.[65]

Government

Bilbao is a municipality with a Mayor-Council form of government. The mayor and councillors are elected to four-year terms. There is a division between an executive branch, made up by the mayor and a board of governors and a Plenum, which consists of 29 councillors.[67] The councillors of the Plenum represent political parties and are distributed as follows: Basque Nationalist Party: 15 seats plus the mayor; People's Party, 6 seats; Bildu, 4 seats; and Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, 4 seats.[68]

In 2008 and 2010, Bilbao won the Municipal Transparency Prize, awarded by the Spanish division of Transparency International. In 2009 it came second, after Sant Cugat del Vallés.[69]

Its former mayor, recently deceased, Mr. Iñaki Azkuna Urreta (PNV-EAJ) was awarded as the Best World Mayor 2012.[70][71]

Districts

The borough of Bilbao consists of eight different districts. Each district is further subdivided into neighbourhoods, totalling 35:

| Number | District | Neighbourhoods | Area (km²) |

Population (2009)[72] |

Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deusto | Arangoiti, Ibarrekolanda, San Ignacio-Elorrieta, and San Pedro de Deusto-La Rivera. | 4.95 | 51,656 | |

| 2 | Uribarri | Castaños, Matiko-Ciudad Jardín, Uribarri, and Zurbaran-Arabella. | 4.19 | 38,335 | |

| 3 | Otxarkoaga-Txurdinaga | Otxarkoaga and Txurdinaga. | 3.90 | 28,518 | |

| 4 | Begoña | Begoña, Bolueta, and Santutxu. | 1.77 | 43,030 | |

| 5 | Ibaiondo | Atxuri, Bilbao La Vieja, Casco Viejo, Iturralde, La Peña, Miribilla, San Adrián, San Francisco, Solokoetxe, and Zabala. | 9.65 | 61,029 | |

| 6 | Abando | Abando and Indautxu. | 2.14 | 51,718 | |

| 7 | Errekalde | Amezola, Iralabarri, Iturrigorri-Peñascal, Errekaldeberri-Larraskitu, and Uretamendi. | 6.96 | 47,787 | |

| 8 | Basurto-Zorroza | Altamira, Basurto, Olabeaga, Masustegi-Monte Caramelo, and Zorrotza. | 7.09 | 33,658 |

Economy

Bilbao has been the economic center of the Basque Country since the times of the Consulate, mainly because of commerce in Castilian products on the town's port, but it was not until the 19th century when it experimented with big development, mainly based on the exploitation of the iron mines and siderurgy, which promoted the maritimal traffic, the portuary activity and the construction of ships.[73] During those years Banco de Bilbao (Bank of Bilbao), founded in Bilbao in 1857 and Banco de Vizcaya (Bank of Biscay), which was established in 1901, also in Bilbao, made their appearance. Both entities merged in 1988 creating the BBV corporation (Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, Bank of Bilbao-Biscay). BBV merged with Argentaria in 1999, creating the current corporation, BBVA. The savings banks that were established locally, Caja de Ahorros Municipal de Bilbao (Municipal Savings Bank of Bilbao) in 1907, and Caja de Ahorros Provincial de Vizcaya (Provincial Savings Bank of Biscay) in 1921, would merge in 1990 and form Bilbao Bizkaia Kutxa (BBK).[74] There is also the Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Navigation of Bilbao and the Stock Exchange Market of Bilbao, founded in 1890.[75]

After the dramatic industrial crisis of the 1980s, Bilbao was forced to rethink its very economic foundations. That is how it transformed into a successful service town.[76] Bilbao is home to numerous companies of national and international relevance, including two among the 150 world's biggest, according to Forbes magazine: BBVA at #40 and Iberdrola at #122.[77] The city's GDP per capita is of €26,225 in 2005, considerably above the country average of €22,152. According to the official economic yearbook, the strongest sectors are construction, commerce, and tourism.[78][79] The unemployment rate reached 14.4% in 2009, well below the national rate, of 18,01%.[80] Nevertheless, it is the highest rate in the last ten years.[81]

Port of Bilbao

The historical port was located in what today is an area called the Arenal, a few steps from the Casco Viejo, until the late 20th century. In 1902, an exterior port was built at the mouth of the estuary, in the coastal municipality of Santurtzi. Further extensions led to a superport, that in the 1970s replaced the docks inside Bilbao,[82] with the exception of those located in the neighbourhood of Zorrotza, still in activity.[83]

The port of Bilbao is a first-class commercial port and is among the top five of Spain.[84] Over 200 regular maritime services link Bilbao with 500 ports worldwide. At the close of 2009 cargo movements amounted to 31.6 million tonnes, Russia, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the Nordic countries being the main markets.[85] In the first semester of 2008, it received over 67,000 passengers and 2,770 ships.[86] This activity reported 419 million euros to the basque GDP and generates almost 10,000 jobs.[87]

Mining and ironworks

Iron is the main and most abundant raw material found in Biscay, and its extraction is legally protected since 1526. Mining was the main primary activity in Bilbao and the minerals, of great quality, were exported to all over Europe.[88] It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century when an ironworks industry was developed, benefited by the resources and the well connected borough. In the 20th century, both Spanish and European capitals imported around 90% of the Biscayan iron.[88] Although World War I made Bilbao one of the main ironworks powers, later crisis prompted a decline in the activity.

Tourism

The first notion of Bilbao as a tourist destination came with the inauguration of the railway between Bilbao and the coastal neighbourhood of Las Arenas, in the municipality of Getxo in 1872. This way, it became a modest beach destination.[89]

However, the real touristic impulse would come with the inauguration of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in 1997, as shown in the increasing tourist arrivals since then, reaching over 615,000 visitors in the year 2009. A significant leap, considering that during 1995, Bilbao only received 25,000 tourists.[90] Bilbao also hosts 31% of the total Basque Country visitors, being the top destination of this autonomous community, above San Sebastián.[90] Most tourists come from within Spain, mainly from Madrid and Catalonia. International travellers come mostly from nearby France, but also from United Kingdom, Germany, and Italy.[90] Tourism generates about 300 million euros for the Biscayan GDP.[90] Bilbao is also an attractive destination for business tourism, mainly thanks to new venues such as the Euskalduna Conference Centre and Concert Hall, or the nearby Bilbao Exhibition Centre, in Barakaldo.[91]

Stock exchange

Projects to create a stock exchange market in Bilbao began in the early 19th century, even though it would not be created until 21 July 1890[75] It is one of Spain's four regional stock exchanges, the other being in Barcelona, Madrid, and Valencia. It is owned by Bolsas y Mercados Españoles. The Bilbao Stock Exchange is considered a secondary market.

Cityscape

Urban planning

In its beginnings, Bilbao only had three streets (Somera, Artecalle, and Tendería) surrounded by walls located where Ronda street now stands. Inside this enclosure, there was a small hermitage dedicated to the Apostle Saint James (the current St. James' Cathedral), which pilgrims visited on their way to Santiago de Compostela. In the fifteenth century, four more streets were built, forming the original Zazpikaleak or "Seven Streets".[92] In 1571, after several floods and a major fire in 1569, the walls were demolished in order to allow the expansion of the town.[93]

In 1861, engineer Amado Lázaro projected an ensanche inside the then-municipality of Abando with wide avenues and regular buildings, that included the hygienists ideas of the time. The project was mostly based on Barcelona's Eixample, designed by Ildefons Cerdà.[94] However, the project was dropped by the City Council after considering it "utopian and excessive" because of its high cost, though of great quality. Furthermore, Lázaro had calculated the demographic growth of the town was based on the previous three centuries, a provision that eventually would not conform to reality.[94][95]

The next large urban change in Bilbao would come in 1876, when the capital annexed (in several stages) the neighbouring municipality of Abando. The new ensanche project was planned by a team made of architect Severino de Achúcarro and engineers Pablo de Alzola (elected Mayor that same year), and Ernesto de Hoffmeyer. Unlike Lázaro's, this project was significantly smaller, compassing 1.58 km2 (0.61 sq mi) against the original 2.54 km2 (0.98 sq mi).[94] It also featured a not so strict grid pattern, a park to separate the industrial and residential areas and the Gran Vía de Don Diego López de Haro, the main thoroughfare, where many relevant buildings were located, such as Biscay County Hall or the BBVA Tower. By the end of the 1890s, this widening was half completed and already filled, so a new extension was planned by Federico Ugalde.[94]

By 1925, the municipalities of Deusto and Begoña, as well as part of Erandio were annexed, and in 1940, the remaining part of Erandio became part of Bilbao. The last annexation took place in 1966, with the municipalities of Loiu, Sondika, Derio, and Zamudio. This made Bilbao larger than ever, with 107 km2 (41 sq mi). However, all these municipalities, with the exception of Deusto and Begoña regained their independence on 1 January 1983.[96]

On 18 May 2010, Bilbao was awarded by the government of Singapore the Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize, at the World Cities Summit 2010.[97] It is considered the Pritzker of urbanism.[98]

Architecture

Bilbao's buildings display a variety of architectural styles, ranging from gothic to contemporary architecture. The Old Town features many of the oldest buildings in the city, as the St. James' Cathedral or the Church of San Antón, included in the borough's coat of arms. Most of the Old Town is a pedestrian zone during the day. Nearby is one of the most important religious temples of Biscay, the Basilica of Begoña, dedicated to the patron saint of the province, Our Lady of Begoña.

Seventeen bridges span the banks of the estuary inside the town's boundaries. Among the most interesting ones are the Zubizuri (Basque for "white bridge"), a pedestrian footbridge designed by Santiago Calatrava opened in 1997, and the Princes of Spain Bridge, also known as "La Salve", a suspension bridge opened in 1972 and redesigned by French conceptual artist Daniel Buren in 2007.[99] The Deusto Bridge is a bascule bridge opened in 1936 and modelled after the Michigan Avenue Bridge, in Chicago.[100] Between 1890 and 1893 the first transporter bridge ("Puente Colgante") in the world on the Nervion river, between Portugalete and Getxo, was built by Alberto Palacio (architect and engineer) together with his brother Silvestre.

Since the deindustrialization process started in the 1990s, many of the former industrial areas are being transformed into modern public and private spaces designed by several of the world's most renowned architects and artists. The main example is the Guggenheim Museum, located in what was an old dock and wood warehouse. The building, designed by Frank Gehry and inaugurated in October 1997, is considered among architecture experts as one of the most important structures of the last 30 years,[101] and a masterpiece by itself.[102] The museum houses part of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation modern art collection. Another example is the Alhóndiga, a wine warehouse built in 1909 and completely redesigned in 2010 by French designer Philippe Starck into a multi-purpose venue that consists of a cinema multiplex, a fitness centre, a library, and a restaurant, among other spaces.[103][104] The Abandoibarra area is also being renovated, and it features not only the Guggenheim Museum, but also Arata Isozaki's tower complex, the Euskalduna Conference Centre and Concert Hall and the Iberdrola Tower, designed by Argentine architect César Pelli which is, since its completion in 2011, the Basque Country's tallest skyscraper, 165 metres (541 ft) high.[105] Zorrozaurre is the next area to be redeveloped, following a 2007 master plan designed by Iraqi architect Zaha Hadid.

This current peninsula will be transformed into a 500,000 m2 (5,400,000 sq ft) island and will feature residential and commercial buildings, as well as the new BBK seat.[106]

Parks

As of 2010, Bilbao has 18 public parks inside its limits, totalling 200 ha (490 acres) of green spaces. Besides, its green belt has a total area of 1,025 ha (2,530 acres), of which 119 ha (290 acres) are urbanized.[107] The largest parks are Mount Cobetas, of 18.5 ha (46 acres), and Larreagaburu, of 12 ha (30 acres), both located on the outskirts.[108]

The Doña Casilda Iturrizar park is located in the district of Abando, near the town centre and covers an area of 8.5 ha (21 acres). It is named after a local benefactress who donated the grounds to the borough. It is an English-style garden designed by Ricardo Bastida and opened to the public in 1907. It features a dancing water fountain surrounded by a pergola, and a pond with many species of ducks, geese and swans, which gives the park the alternate name of "Ducks' Park", as known locally. In recent years, it was expanded to be connected with the Abandoibarra area.[109] In Ibaiondo, the Etxeberria Park was built in the 1980s in the place where a steel mill previously stood. The original chimney was maintained as a homage of its industrial past. It covers an area of 18.9 ha (47 acres), on a sloped terrain that overlooks the Old Town.[110] Other relevant public spaces inside the city include the Europa Park, the Miribilla Park, or the Memorial Walkway, a 3 km (1.9 mi) long walkway, with 12 m (39 ft) high lamps, located in the left bank of the estuary and that connects the main sights.[111]

Mount Artxanda is easily accessible from the town centre by a funicular. There is a recreational area at the summit, with restaurants, a sports complex and a balcony with panoramic views. In the south, Mount Pagasarri receives hundreds of hikers every weekend since the 1870s, who seek its natural wonders. Its environment is officially protected since 2007.[112]

Education

The Basque Country has a bilingual education system, with students having the possibility to choose between four linguistic models: A, B, D, and X, which differ in the prevalence of Basque or Spanish as the spoken and written language during classes.[113] In Bilbao, there is a prevalence of model D (Basque is the vehicle language and Spanish is taught as a subject) in Primary School, while Compulsory Secondary Education students favour model B (some subjects are in Basque and other in Spanish). Finally, 67% of Baccalaureate students choose model A (Spanish is the vehicle language and Basque is a subject).[114] English is the most widespread foreign language taught, as it is the option for 97% of pre-university students.[113]

Higher education

Bilbao is home to two universities. The oldest is the University of Deusto, founded by the Society of Jesus in 1886. It took its name after the then independent municipality of Deusto, annexed to Bilbao in 1925. It was the only higher education offered in the borough until the establishment in 1968 of the University of Bilbao, that would later become the University of the Basque Country in 1980. This public university, present in the three provinces of the autonomous community, has its main Biscayan campus in the municipality of Leioa, however the Technical and Business faculties are based in Bilbao.[115]

Transport

Bilbao Airport serves the city and it is the busiest terminal in the Basque Country and in the entire Northern coast, with 3,9 million passengers in 2010.[116][117] It is located 12 km (7.46 mi) north of the borough, between the municipalities of Loiu and Sondika.[118] 15 airlines operate in the terminal, including Iberia, Lufthansa, and TAP Portugal. Top destinations include London, Frankfurt, Munich, Madrid, Paris, Malaga, and Amsterdam.[117] It opened to the public in September 1948, with a regular flight to Madrid. On 19 November 2000, a new terminal building was opened, designed by Valencian architect Santiago Calatrava. In February 2009, a project was approved to expand the current building to double its capacity. Although expected to be completed by 2014, the current financial crisis and the decrease of passenger traffic delayed it to at least 2019.[119]

The borough has 13 bridges connecting opposite sides of the river. It is connected to the European road network by the AP-8 toll motorway and to the north of Spain by the A-8 motorway and to the rest of Spain by the AP-68 toll motorway.

The underground network (Metro Bilbao), opened on 11 November 1995, is used by more than 85 million passengers every year. It has 2 lines that connect both banks of the Bilbao Metropolitan Area. There is a project under way to build a third line.

The city has 43 Bilbobus bus lines, 28 for normal buses, seven "micro-buses" for zones of the city that a normal bus cannot access, and eight night lines. The inner-town bus network has recently won a prize for its efficiency and quality of service. In addition, there are more than 100 BizkaiBus bus lines, connecting Bilbao with almost every point in Biscay and part of Alava. The borough's main bus station is called Termibus and is located near the San Mamés stadium.

There are 7 commuter rail lines operated by three different companies:

Renfe (Spanish railway network) operates 3 Cercanías lines in metropolitan Bilbao:

- C1, Bilbao-Abando–Santurtzi

- C2, Abando-Muskiz

- C3, Abando-Orduña

FEVE (Spanish Narrow Gauge Railways) operates one line:

- Abando (Concordia)-Balmaseda.

EuskoTren (Basque railway network), operates three lines:

In 2002, the new tram, EuskoTran, was inaugurated. It has one line connecting Atxuri with Basurto. Plans are afoot to greatly expand the network over the coming decade.

A Brittany Ferries ferry service links Santurtzi, near Bilbao, to Portsmouth (UK). MV Cap Finistère ferry departs from the port of Bilbao, 15 km (9 mi) north west of the town centre. A service operated by Acciona Trasmediterranea served the same route from 16 May 2006 until April 2007. P&O Ferries operated this route until its withdrawal on 28 September 2010 with a ship called the Pride of Bilbao.

Culture

Bilbao has several theatres and concert halls (Teatro Arriaga, Palacio Euskalduna), cinemas, and a regular opera season offered by ABAO (Bilbao Association of Opera Lovers) . The Bilbao Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1922, its current conductor Günter Neuhold being appointed in 2008. Choral music is very popular in the Basque Country and concerts are offered regularly. The Bilbao Choral Society (Sociedad Coral de Bilbao) was founded in 1886.

Like in other Spanish town, night life is long and vibrant, with clubs that offer live music (Kafe Antzokia, Bilborock).

Bilbao was briefly featured at the start of the 1999 James Bond film The World Is Not Enough.

The Bilbao Live Festival, first held in 2006, is an increasingly popular live music event.[120]

Museums

Bilbao´s Museums offers more than a dozen of institutions covering different fields such as art, science and sport.

Museums include the famous Guggenheim Museum Bilbao[121] of contemporary art, which was made by Frank Gehry and was opened on the 19th of October 1997. Another important Museum is the Bilbao Fine Arts Museum,[122] which was created on 1908 with a great collection of Spanish painting. Related to science there is the Archaeological, Ethnographical and Historical Basque Museum, which preserves objects and realizes exhibitions regarding the Basque past.

Festival

Semana Grande (Spanish for Big Week, Aste Nagusia in Basque) is Bilbao's main festival attracting over 100,000 people. It begins on the Saturday of the 3rd week of August each year, lasting 9 days and has been celebrated since 1978. People from around Spain, and increasingly from abroad, attend the celebrations.

The celebrations include the strongman games, free music performances, street entertainment, bullfighting and nightly firework displays. The best views of the display are from the town's bridges. Each year, there is something different occurring, thus a festival programme (these are available all over the city) is strongly recommended.

Sport

Like in the rest of Spain, football is the most popular competitive sport, followed by basketball.

The main football club is Athletic Club, commonly known as Athletic Bilbao in English. It plays at the new San Mamés stadium, which opened in 2013 and seats 53,332 spectators.[123] Athletic Bilbao was one of the founding members of the Spanish football league, La Liga, and has played in the Primera División (First Division)[124] ever since - winning it on eight occasions. Its red and white striped flag is seen throughout the city. Athletic are noted for its Basque policy, with only players born in or having clear connection to the Basque Country or Navarre being allowed to represent the club.

The main basketball team is CB Bilbao Berri aka Bizkaia Bilbao Basket, which plays in the ACB. Their home venue is the Bilbao Arena.

In addition, Bilbao offers many outdoor activities owing to its location in a hilly countryside. Hiking is very popular as well as rock climbing in the nearby mountains. Watersports, especially surfing, are practiced on the beaches of nearby Sopelana and Mundaka.

Outstanding people from Bilbao

- Joaquín Achúcarro (1932). Pianist.

- Nicolás Achúcarro (1880-1918). Neuroscientist medical.

- José Antonio Aguirre (1904-1960). Football player,[125] Nationalist politician and first lehendakari of Basque Government .

- Gabriel Aresti (1933-1975). Promoter of poetry in euskera.

- Nicolás de Arriquibar (1714-1779). Economist.

- Juan Crisóstomo de Arriaga (1806-1826). Composer, violinist and orchestra conductor.

- Pedro Arrupe (1907-1991). Jesuit priest. Superior General of the Jesuits between 1965 and 1983.

- Álex de la Iglesia (1965). Film director and scriptwriter.

- Casilda Iturrizar (1818-1900). Philanthropist.

- Juan Larrea (1895-1980). Poet and essayist.

- José de Mazarredo (1745-1812). Admiral. Director General of the Navy.

- Rafael «Pichichi» Moreno (1892-1922). Football player.

- Blas de Otero (1916-1979). Poet.

- Ramiro Pinilla (1923). Writer.

- José Joaquín Puig de la Bellacasa (1931). Diplomat, jurist and ambassador to Spain.

- Juan Martínez de Recalde (c.1526-1588). Admiral.

- Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936). Writer and philosopher.

- Secundino Zuazo (1887-1970). Architect and urbanist.

- Joaquín Almunia Amann (1948). Parliamentarian and minister of Spain and commissioner of the European Union.

- Pedro Olea (1938). Director, productor and film scriptwriter.

- Fito Cabrales (1966). Singer, guitarrist y composer.

- Sabino Arana (1865-1903). Politician and writer. Fundator of PNV.

- José María Basterra y Madariaga (1862-1934). Architect.

- Terele Pávez (1939). Actress and Emma Penella and Elisa Montes sister.

- Anabel Ochoa (1955-2008). Psychiatrist, communicologist, writer and actress of Los monólogos de la vagina.

- Txus di Fellatio, Jesús María Hernández Gil (1970). Lyricist, poet and Mägo de Oz folk metal drummer .

- Mariví Bilbao (1930-2013). Actress.

- Txomin Badiola (1957). Sculptor.

- Olivia Martínez, «La Greca» (1937). Singer, dancer and Spanish bullfighter.

- Jon Kortajarena (1985). Actor and international model.

- Cristina Diago (1989) Media Executive.

Twin cities

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

Bilbao is twinned with:

Monterrey, Mexico

Monterrey, Mexico Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires, Argentina Rosario, Argentina[126]

Rosario, Argentina[126] Medellín, Colombia

Medellín, Colombia Bordeaux, France[127][128]

Bordeaux, France[127][128] Qingdao, People's Republic of China

Qingdao, People's Republic of China Tbilisi, Georgia[129]

Tbilisi, Georgia[129] Pittsburgh, United States

Pittsburgh, United States Sant Adrià de Besòs, Spain

Sant Adrià de Besòs, Spain

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Tabla158". Ine.es. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "Define Bilbao". reference.com. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "List of place names". National Statistics Institute. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Urban zones in Spain. World Gazetteer". Population-statistics.com. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "Functional area. Bilbao Metropolitan Area" (PDF). Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ Proyecto Audes[dead link]

- ^ "Population by province and sex". Basque Statistics Office. 31 December 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Quiroga 2001: 17

- ^ a b De La Puerta Rueda 1998: 73

- ^ Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 169

- ^ "Mission Statement". Bilbao Guggenheim Museum. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Iglesias, Lucía (September 1998). "Bilbao: The Guggenheim effect" (PDF). The UNESCO Courier. UNESCO: 41. ISSN 0041-5278.

- ^ a b "Europe needs to multiply 'Guggenheim effect' to stay attractive, Hübner tells World Investment Conference in La Baule". europa.eu. 5 June 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Proyectos de Bilbao". elcorreo.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Euskal Onomastikaren Datutegia" (in Basque). Euskaltzaindia. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Dueñas Beraiz, Germán (2001). "La producción de armas blancas en Bilbao durante el Siglo XVI". Gladius XXI. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ Shakespeare's military language. Books.google.co.uk. 2004. ISBN 9780826477774. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ Beascoechea 1999: 138

- ^ "Bilbo". Encyclopædia Britannica 11th Edition. 1911. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ^ Historia de Vizcaya a través de la prensa, Volume 2

- ^ a b Quiroga 2001: 41

- ^ Tusell 2004: 22.

- ^ Adeliño Ortega, Charo. "Carta Puebla" (PDF). Bilbao 700. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ GUIARD LARRAURI, Teófilo y RODRÍGUEZ HERRERO, Ángel: Historia de la Noble Villa de Bilbao. Editorial La Gran Enciclopedia Vasca, 1971. pag. 8

- ^ AZPIAZU CANIVELL, Mª Dolores. euskonews.com (ed.). "La Sociedad El Sitio. Más de 130 años de liberalismo bilbaíno". Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Asociación de Periodistas de Vizcaya. "Crónica de siete siglos" (PDF). Bilbao 700. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Sánchez-Beascoetxea 2006: 28

- ^ Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 96

- ^ Tussel Gómez 2004: 19

- ^ Tussel Gómez 2004: 26

- ^ Beascoechea 1999: 104

- ^ "Un día perfecto en Bermeo y Gernika". Bilbaoport.es. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Quiroga 2001: 68

- ^ Sánchez-Beaskoetxea 2006: 42

- ^ Sánchez-Beaskoetxea 2006: 44

- ^ Montero, Manuel. "Crónica de siete siglos" (PDF). Bilbao 700. p. 48. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ Quiroga 2001: 84

- ^ Sánchez-Beaskoetxea 2006: 48

- ^ Tussel 2004: 187

- ^ a b c Quiroga 2001: 96

- ^ Tussel 2004: 194

- ^ "Agentes del proceso de revitalización". BM30. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ "BILBAO Ría 2000 – ¿Qué es?". Bilbao Ría 2000. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ Montero 1998: 37.

- ^ "Superficie, población y densidad por distritos. 2007" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. 2007. Retrieved 19 July 2008.

- ^ Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 35

- ^ a b c Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 38

- ^ "Plano callejero de Bilbao" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ Orive, Emma and Rallo, Ana (October 2002). "Ríos de Bizkaia". Diputación Foral de Bizkaia: Instituto de Estudios Territoriales de Bizkaia. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Saiz Salinas, José I. "Bioindicadores de recuperación en la Ría de Bilbao". euskonews.com. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 77

- ^ Uriarte, Iñaki (March 2006). "La ría y el canal de Deustu" (PDF). Periódico Bilbao. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Santos Sabrás 1998: 60

- ^ "Las obras de urbanización de Zorrozaurre, en Bilbao, que tendrán un coste de 291 millones de euros, comenzarán en 2010". Deia. 5 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 July 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- ^ "Vuelve la vida a la Ría de Bilbao". bajoelagua.com. 7 February 2006. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "La regeneración natural de la ría de Bilbao evita acometer su limpieza". El País. 22 January 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- ^ "La ría recupera los bañistas". El Correo. 2 July 2010. Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 65

- ^ Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 70

- ^ "City Council climate information". Bilbao City Council. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Guía resumida del clima en España (1981-2010)". AEMET. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Monthly Weather Averages for Bilbao Airport". Aena. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ a b Gómez Piñeiro 1979: 96

- ^ "Evolución de la Población de Bilbao 1900 – 2007" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ a b "Población según lugar de nacimiento, sexo y edad" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Inmigración extranjera en Bilbao" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. 1 January 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Nature, Attributions and Organisation". Ayuntamiento de Bilbao. Retrieved 10 October 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "2011 Election Results". elpais.com. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ "Reconocimientos y premios 2000–2010". Ayuntamiento de Bilbao. Retrieved 10 October 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Galarraga, Naiara (19 January 2003). "Una legislatura de gobierno nacionalista en minoría". El País (in Spanish). Edicíones El País. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ Surio, Alberto (17 June 2007). "Tensión del PNV con EA por dejarle sin las alcaldías de Azpeitia y Zumaia". El Diario Vasco (in Spanish). Sociedad Vascongada de Publicaciones, S.A. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- ^ "Territorio y climatología" (PDF). Ayuntamiento de Bilbao. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ http://www.bilbao.net/nuevobilbao/jsp/bilbao/pwegb010.jsp?idioma=C&color=rojo&padre=%7CHT&tema=FBS&subtema=10&padresub=*M4&textarea=*M4

- ^ "bbk 100 años". Portal.bbk.es. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Bilbao 700 – Capítulo VI" (PDF). Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ "Historia de Bilbao". Ayuntamiento de Bilbao. Retrieved 16 October 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Del Moral, José (22 August 2008). "BBVA, Iberdrola y Gamesa son las mayores empresas vascas, según Forbes". cybereuskadi.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Anuario Socioeconómico de Bilbao 2006" (PDF). Lan Ekintza. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ "El PIB de Bilbao supuso en 2006 la mitad del valor total de Euskadi". Deia. 18 December 2007. Retrieved 16 October 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "4.2 Tasas de paro por sexo y grupo de edad". INE. Archived from the original on 13 November 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Empleo" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Corres Abásolo, José Ángel. "El Puerto: Desde San Antón al Abra" (PDF). Bilbao 700. p. 212. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ "El Puerto abandonó ayer el Canal de Deusto tras 38 años de actividad comercial". Deia. 8 February 2006. Retrieved 31 October 2007. [dead link]

- ^ "Preguntas frecuentes". Puerto de Bilbao. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Port of Bilbao throughput stood at 31.6 million tonnes in 2009". Puerto de Bilbao. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Estadísticas generales". Puerto de Bilbao. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ "Economical impact". Puerto de Bilbao. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ a b Diez Alday, José Antonio. "Bessemer cambió la historia" (PDF). Bilbao 700. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ Montero, Manuel (2005). p. 97.

- ^ a b c d El Correo, ed. (1 October 2010). "Bilbao ya no es sólo una ciudad de paso". Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Etxebarria, Elvira. "En posición privilegiada" (PDF). Bilbao 700. p. 236. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ Tusell 2004: 19

- ^ Arizaga Balumburu, Beatriz and Martínez Martínez, Sergio. "El espacio público de la villa de Bilbao" (PDF). euskomedia.org. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Bilbao (Urbanismo, siglos XIX y XX)". euskomedia.org. Retrieved 8 October 2010.

- ^ Montero 2000: 45

- ^ "BOE del País Vasco". Basque Government. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- ^ "Bilbao City Hall tops 78 nominations to clinch the inaugural Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize". Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Medalla de oro, certificado y 176.000 euros de premio". El Correo. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "Red Arches". Guggenheim Bilbao. 20 October 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "El puente de Deusto afronta su primera reforma integral tras 70 años de servicio". Deia. 23 April 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Tyrnauer, Matt (30 June 2010). "Architecture in the Age of Gehry". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Parr, Linda (2007). "Perfect Space" (PDF). Artists & Illustrators. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "The Alhóndiga, Culture". Alhóndiga Bilbao. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "La nueva Alhóndiga". El Correo. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Presentation". Torre Iberdrola. Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ "Seguirá quedando claro el estilo de Zaha Hadid". El Correo. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Ibilbide Luzea – Gran Recorrido" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- ^ "Parques urbanos". Bilbao City Council. Retrieved 11 November 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Doña Casilda Park". Bilbao City Council. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Etxebarria Park". Bilbao City Council. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Memorial Walkway". Bilbao City Council. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Pagasarri: Our closest mountain" (PDF). Bilbao City Council. 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ a b Cenoz, Jasone; Jessner, Ulrike (2000). English in Europe: the acquisition of a third language. Multilingual Matters. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9781853594793.

- ^ "Hezkuntza" (PDF). Bilbao City Hall. 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Centros". UPV-EHU. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ^ "Tráfico de pasajeros, operaciones y carga en los aeropuertos españoles" (PDF). Aena. 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ a b "El tráfico de pasajeros del aeropuerto de Loiu creció un 6,4% en 2010". deia.com. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ Aena (ed.). "Cómo llegar". Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ "La ampliación del aeropuerto de Bilbao se retrasa al menos 5 años". El Correo. 19 November 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ "Bilbao Turismo". .bilbao.net. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Guggenheim Museum Bilbao".

- ^ "Bilbao Fine Arts Museum".

- ^ Gunther Lades. "Football stadiums of the world – Stadiums in Spain". Fussballtempel.net. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ "Spanish Primera División Table - ESPN Soccernet". Soccernet.espn.go.com. 11 June 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ athletic-club.net (ed.). "Historia". Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ^ "Town Twinning Agreements". Municipalidad de Rosario - Buenos Aires 711. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Bordeaux - Rayonnement européen et mondial". Mairie de Bordeaux (in French). Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Bordeaux-Atlas français de la coopération décentralisée et des autres actions extérieures". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Tbilisi Sister Cities". Tbilisi City Hall. Tbilisi Municipal Portal. Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=

Bibliography

- Beascoechea Madina, José María (1999). Bilbao en el espejo. La Bilbao más antigua 1300/1700. Bilbao. p. 194. ISBN 84-605-7844-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gómez Piñeiro, Francisco Javier; et al. (1979). Geografía de Euskal Herria: Vizcaya. San Sebastián. p. 291. ISBN 84-7407-068-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Montero, Manuel (2000). Construcción histórica de la villa de Bilbao. San Sebastián. p. 142. ISBN 84-7148-384-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Olaizola Elordi, Juanjo (2002). Bilboko tranbiak-Los tranvías de Bilbao (PDF). Bilbao. p. 177. ISBN 84-920629-8-3. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[dead link] - Pérez Pérez, José Antonio (2001). Bilbao y sus barrios: una mirada desde la historia. Bilbao. ISBN 978-84-88714-94-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Quiroga, Ramón; Marrodán, Miguel Ángel (2001). Bilbao: 700 años de historia. Abanto y Ciérvana. p. 115. ISBN 84-931494-3-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sánchez-Beaskoetxea, Javier (2006). La vuelta a Bilbao a través de sus montes y de su historia. Bilbao. p. 94. ISBN 978-84-88714-93-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Tusell Gómez, Javier (2004). Bilbao a través de su Historia. Bilbao. p. 212. ISBN 84-95163-91-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - V.A. (October–December 1998). La Ría, una razón de ser. Bilbao. p. 147.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - V.A. (2000). El karst de Pagasarri. ISBN 84-7752-319-3.

- García de la Torre, Francisco Javier (2009). Bilbao : arquitectura. ISBN 9788461328703.