American ginseng

| American ginseng | |

|---|---|

| |

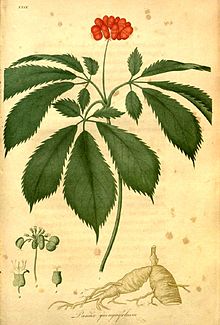

| Panax quinquefolius[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. quinquefolius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panax quinquefolius | |

American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) is a herbaceous perennial plant in the ivy family, commonly used as Chinese or herbal medicine. An extract is sold as Cold-fX. It is native to eastern North America, though it is also cultivated in places such as China.[3][4]

The plant's forked root and leaves were traditionally used for medicinal purposes by Native Americans. Since the 18th century, the roots have been collected by "sang hunters" and sold to Chinese or Hong Kong traders, who often pay very high prices for particularly old wild roots.[5] It is also known by its Chinese name huaqishen (simplified Chinese: 花旗参; traditional Chinese: 花旗參; pinyin: huāqíshēn; Jyutping: faa1kei4sam1; lit. 'Flower Flag ginseng') or xiyangshen (simplified Chinese: 西洋参; traditional Chinese: 西洋參; pinyin: xīyángshēn; Jyutping: sai1joeng4sam1; lit. 'west ocean ginseng').

Medical uses

Health Canada's Natural Health Product Directorate states that extracts from American ginseng "help reduce the frequency, severity and duration of cold and flu symptoms by boosting the immune system".[6]

Some manufacturer-sponsored trials suggest that extracts from American ginseng, when used preventively, may have favorable effects on elderly patients against common cold. However, the results of these trials are inconsistent, and the trials of substandard quality.[7] There is no scientific evidence showing that American ginseng is effective in treating those who are already infected with the common cold.[8]

Adverse effects

Reported side effects of use of American ginseng include headache, gastrointestinal upset, anxiety, and insomnia. Ginseng should be avoided during pregnancy and lactation because of potential teratogenicity and estrogenic effects. Case reports have described potential herb-drug interactions with phenelzine (induction of mania from depression), warfarin (increased international normalized ratio), and alcohol (increased blood clearance).[9]

During its growth, harvest, processing, and storage, the American ginseng can be polluted by molds, pesticides, heavy metals, and other chemicals, resulting in contamination with mycotoxins, pesticide residues, and heavy metals, as well as other substances harmful to human health.[10] However, it must be noted that, in typical modern diets, the contribution of these harmful substances from American ginseng is minuscule compared with that from normal intake of food and drink or the environment.[citation needed]

Production

American ginseng was formerly particularly widespread in the Appalachian and Ozark regions (and adjacent forested regions such as Pennsylvania, New York and Ontario), but due to its popularity and unique habitat requirements, the wild plant has been overharvested, as well as lost through destruction of its habitat, and is thus rare in most parts of the United States and Canada.[11] Ginseng is also negatively affected by deer browsing, urbanization, and habitat fragmentation.[12] It can also be grown commercially, under artificial shade, woods cultivated, or wild-simulated methods and is usually harvested after three to four years depending on cultivation technique; the wild-simulated method often requires up to 10 years before harvest.

Ontario, Canada is the world's largest producer of North American ginseng.[13] Marathon County Wisconsin, accounts for about 95% of production in the United States.[14]

-

American ginseng in human figure

-

Under wooden shade, American ginseng in late fall at Monk Garden in Wisconsin

-

American ginseng berries are ripe by late fall in Wisconsin.

Chemical components

Like Panax ginseng, American ginseng contains dammarane-type ginsenosides, or saponins, as the major biologically active constituents. Dammarane-type ginsenosides include two classifications: 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (PPD) and 20(S)-protopanaxatriol (PPT). American ginseng contains high levels of Rb1, Rd (PPD classification), and Re (PPT classification) ginsenosides—higher than that of P. ginseng in one study.[15]

Pharmacokinetics

When taken orally, PPD-type ginsenosides are mostly metabolized by intestinal bacteria (anaerobes) to PPD monoglucoside, 20-O-beta-D-glucopyranosyl-20(S)-protopanaxadiol (M1).[16] In humans, M1 is detected in plasma from seven hours after intake of PPD-type ginsenosides and in urine from 12 hours after intake. These findings indicate M1 is the final metabolite of PPD-type ginsenosides.[17]

M1 is referred to in some articles as IH-901,[18] and in others as compound-K.[17]

Society and culture

Cold-fX is a product derived from the roots of North American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius). Originally manufactured by Afexa Life Sciences Inc. (formerly called CV Technologies Inc.),[19] headquartered in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, the company and lead product was acquired by Valeant Pharmaceuticals International (headquartered in Laval, Quebec, Canada) in 2011.

The makers of Cold-fX, were criticized for making health claims about the product that have never been tested or verified scientifically. Up until February 2007, the company advised a regimen of 18 pills over a course of 3 days in order to obtain "immediate relief" from a cold. Health Canada's review of the scientific literature confirmed that this is not a claim that CV Technologies Inc. is entitled to make.[20]

References

- ^ Panax_quinquefolius L., from "American medical botany being a collection of the native medicinal plants of the United States, containing their botanical history and chemical analysis, and properties and uses in medicine, diet and the arts" by Jacob Bigelow,1786/7-1879. Publication in Boston by Cummings and Hilliard,1817-1820.

- ^ "Panax quinquefolius". NatureServe Explorer. NatureServe. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ^ Xiang, Q.; Lowry, P. P. (2007). "Araliaceae". In Wu, Z. Y.; Raven, P. H.; Hong, D. Y. (ed.). Flora of China (pdf). Vol. 13. St. Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden Press. p. 491. ISBN 9781930723597.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ "Panax quinquefolius". eFloras.

- ^ There is More to a Forest than Trees. research.vt.edu (Summer 2002)

- ^ http://webprod3.hc-sc.gc.ca/lnhpd-bdpsnh/info.do?lang=eng&licence=80002849

- ^ Nahas, R; Balla, A (Jan 2011). "Complementary and alternative medicine for prevention and treatment of the common cold". Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 57 (1): 31–6. PMC 3024156. PMID 21322286.

Poor and misleading reporting of data makes it difficult to draw conclusions from these studies.

- ^ Nahas, R; Balla, A (Jan 2011). "Complementary and alternative medicine for prevention and treatment of the common cold". Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 57 (1): 31–6. PMC 3024156. PMID 21322286.

There are no trials evaluating ginseng for treatment of the common cold.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Nah2011was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Wang, Zengui; Huang, Linfang (March 2015). "Panax quinquefolius: An overview of the contaminants". Phytochemistry Letters. 11: 89-94. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2014.11.013.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Beattie-Moss, M. (2006-06-19). "Roots and Regulations - The unfolding story of Pennsylvania ginseng". Pennstate news.

- ^ McGraw, J. "Population Biology and Conservation Ecology of American Ginseng". West Virginia University.

- ^ "Industry Information | Ontario Ginseng Growers Association". http://ginsengontario.com/. Ontario Ginseng Growers Association. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Ginseng Prices at Highest in Decades". The Post Crescent. October 19, 2010.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Zhu, S.; Zou, K.; Fushimi, H.; Cai, S.; Komatsu, K. (2004). "Comparative study on triterpene saponins of ginseng drugs". Planta Medica. 70 (7): 666–677. doi:10.1055/s-2004-827192. PMID 15303259.

- ^ Hasegawa, H.; Sung, J.-H.; Matsumiya, S.; Uchiyama, M. (1996). "Main ginseng saponin metabolites formed by intestinal bacteria". Planta Medica. 62 (5): 453–457. doi:10.1055/s-2006-957938. PMID 8923812.

- ^ a b Tawab, M. A.; Bahr, U.; Karas, M.; Wurglics, M.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M. (2003). "Degradation of ginsenosides in humans after oral administration". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 31 (8): 1065–1071. doi:10.1124/dmd.31.8.1065. PMID 12867496.

- ^ Oh, S.-H.; Lee, B.-H. (2004). "A ginseng saponin metabolite-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells involves a mitochondria-mediated pathway and its downstream caspase-8 activation and Bid cleavage". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 194 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2003.09.011. PMID 14761678.

- ^ "What is COLD-fX intended for?". Cold-fX: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Charlie Gillis (2007-03-26). "COLD-fX catches the sniffles again". Macleans Magazine.

External links

- "There is More to a Forest than Trees" by Lynn Davis, College of Natural Resources, Virginia Tech

- "Roots and Regulations: The Unfolding Story of Pennsylvania Ginseng", by Melissa Beattie-Moss