al-Qaeda

| Al-Qaeda | |

|---|---|

| القاعدة | |

Shahada flag | |

| Leaders | Abdallah Azzam (1988–1989) Osama bin Laden (1989–2011) Ayman al-Zawahiri (2011–present) |

| Dates of operation | 1988–present |

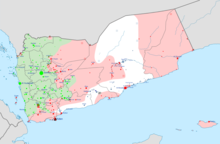

| Active regions | Worldwide Predominantly in the Middle East Rebel group with current territorial control in: |

| Ideology | Salafism Salafist jihadism[4][5][6] Qutbism[7] Sunni supremacy[8] Pan-Islamism[9][10][11][12][13] |

| Allies | |

| Battles and wars | In Afghanistan Before War on Terror

In Tajikistan In Chechnya In Yemen In Afghanistan In the Maghreb In Iraq In Pakistan In Somalia In Syria |

Al-Qaeda (/ælˈkaɪdə/ or /ˌælkɑːˈiːdə/; Template:Lang-ar al-qāʿidah, Arabic: [ælqɑːʕɪdɐ], translation: "The Base", "The Foundation" or "The Fundament" and alternatively spelled al-Qaida, al-Qæda and sometimes al-Qa'ida) is a global militant Sunni Islamist organization founded by Osama bin Laden, Abdullah Azzam,[26] and several others,[27] at some point between August 1988[28] and late 1989,[27] with origins traceable to the Arab volunteers who fought against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in the 1980s.[29][30] It operates as a network comprising both a multinational, stateless army[31] and an Islamist, extremist, wahhabi jihadist group.[32] It has been designated as a terrorist group by the United Nations Security Council, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union, the United States, Russia, India, and various other countries (see below). Al-Qaeda has carried out many attacks on targets it considers kafir.[33]

Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military targets in various countries, including the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings, the September 11 attacks, and the 2002 Bali bombings. The U.S. government responded to the September 11 attacks by launching the "War on Terror". With the loss of key leaders, culminating in the death of Osama bin Laden, al-Qaeda's operations have devolved from actions that were controlled from the top down, to actions by franchise associated groups and lone-wolf operators. Characteristic techniques employed by al-Qaeda include suicide attacks and the simultaneous bombing of different targets.[34] Activities ascribed to it may involve members of the movement who have made a pledge of loyalty to Osama bin Laden, or the much more numerous "al-Qaeda-linked" individuals who have undergone training in one of its camps in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq or Sudan who have not.[35] Al-Qaeda ideologues envision a complete break from all foreign influences in Muslim countries, and the creation of a new caliphate ruling over the entire Muslim world.[9][36][37] During the Syrian civil war, al-Qaeda factions started fighting each other, as well as the Kurds and the Syrian government.

Among the beliefs ascribed to al-Qaeda members is the conviction that a Christian–Jewish alliance is conspiring to destroy Islam.[38] As Salafist jihadists, they believe that the killing of non-combatants is religiously sanctioned, but they ignore any aspect of religious scripture which might be interpreted as forbidding the murder of non-combatants and internecine fighting.[4][39] Al-Qaeda also opposes what it regards as man-made laws, and wants to replace them with a strict form of sharia law.[40]

Al-Qaeda is also responsible for instigating sectarian violence among Muslims.[41] Al-Qaeda leaders regard liberal Muslims, Shias, Sufis and other sects as heretics and have attacked their mosques and gatherings.[42] Examples of sectarian attacks include the Yazidi community bombings, the Sadr City bombings, the Ashoura massacre and the April 2007 Baghdad bombings.[43] Since the death of Osama bin Laden in 2011 the group has been led by Egyptian Ayman al-Zawahiri.

Organization

Al-Qaeda's management philosophy has been described as "centralization of decision and decentralization of execution."[44] It is thought that al-Qaeda's leadership, following the War on Terror, has "become geographically isolated," leading to the "emergence of decentralized leadership" of regional groups using the al-Qaeda "brand".[45][46]

Many terrorism experts do not believe that the global jihadist movement is driven at every level by al-Qaeda's leadership. Although bin Laden still held considerable ideological sway over some Muslim extremists before his death, experts argue that al-Qaeda has fragmented over the years into a variety of regional movements that have little connection with one another. Marc Sageman, a psychiatrist and former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) officer, said that al-Qaeda is now just a "loose label for a movement that seems to target the West." "There is no umbrella organisation. We like to create a mythical entity called [al-Qaeda] in our minds, but that is not the reality we are dealing with."[47]

This view mirrors the account given by Osama bin Laden in his October 2001 interview with Tayseer Allouni:

"... this matter isn't about any specific person and... is not about the al-Qa'idah Organization. We are the children of an Islamic Nation, with Prophet Muhammad as its leader, our Lord is one... and all the true believers [mu'mineen] are brothers. So the situation isn't like the West portrays it, that there is an 'organization' with a specific name (such as 'al-Qa'idah') and so on. That particular name is very old. It was born without any intention from us. Brother Abu Ubaida... created a military base to train the young men to fight against the vicious, arrogant, brutal, terrorizing Soviet empire... So this place was called 'The Base' ['Al-Qa'idah'], as in a training base, so this name grew and became. We aren't separated from this nation. We are the children of a nation, and we are an inseparable part of it, and from those public *** which spread from the far east, from the Philippines, to Indonesia, to Malaysia, to India, to Pakistan, reaching Mauritania... and so we discuss the conscience of this nation."[48]

Others, however, see al-Qaeda as an integrated network that is strongly led from the Pakistani tribal areas and has a powerful strategic purpose. Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism expert at Georgetown University, said "It amazes me that people don't think there is a clear adversary out there, and that our adversary does not have a strategic approach."[47]

Al-Qaeda has the following direct affiliates:

Al-Qaeda's indirect affiliates includes the following, many of which have left the organization and joined the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant:

- Al-Mulathameen Brigade

- Ansar Dine

- Abu Sayyaf (pledged allegiance to ISIL[52])

- Ansar al-Islam (merged with ISIL on 29 August 2014)

- East Turkestan Islamic Movement

- Caucasus Emirate

- Fatah al-Islam

- Islamic Jihad Union

- Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan

- Jaish-e-Mohammed

- Jemaah Islamiyah

- Lashkar-e-Taiba

- Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa

- Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group

- Rajah Sulaiman movement

Leadership

Information mostly acquired from Jamal al-Fadl provided American authorities with a rough picture of how the group was organized. While the veracity of the information provided by al-Fadl and the motivation for his cooperation are both disputed, American authorities base much of their current knowledge of al-Qaeda on his testimony.[53]

Osama bin Laden was the most historically notable emir, or commander, and Senior Operations Chief of al-Qaeda prior to his assassination on May 1, 2011 by US forces. Ayman al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda's Deputy Operations Chief prior to bin Laden's death, assumed the role of commander, according to an announcement by al-Qaeda on June 16, 2011. He replaced Saif al-Adel, who had served as interim commander.[54]

Bin Laden was advised by a Shura Council, which consists of senior al-Qaeda members, estimated by Western officials to consist of 20–30 people.

Atiyah Abd al-Rahman was alleged to be second in command prior to his death on August 22, 2011.[55]

On June 5, 2012, Pakistan intelligence officials announced that al-Rahman's alleged successor Abu Yahya al-Libi had been killed in Pakistan.[56]

Nasir al-Wuhayshi was said to have become second in command in 2013. He was the leader of Al Qaeda in Yemen until killed in a U.S. airstrike in June 2015.[57]

Al-Qaeda's network was built from scratch as a conspiratorial network that draws on leaders of all its regional nodes "as and when necessary to serve as an integral part of its high command."[58]

- The Military Committee is responsible for training operatives, acquiring weapons, and planning attacks.

- The Money/Business Committee funds the recruitment and training of operatives through the hawala banking system. U.S-led efforts to eradicate the sources of terrorist financing[59] were most successful in the year immediately following the September 11 attacks.[60] Al-Qaeda continues to operate through unregulated banks, such as the 1,000 or so hawaladars in Pakistan, some of which can handle deals of up to $10 million.[61] It also provides air tickets and false passports, pays al-Qaeda members, and oversees profit-driven businesses.[62] In the 9/11 Commission Report, it was estimated that al-Qaeda required $30 million-per-year to conduct its operations.

- The Law Committee reviews Sharia law, and decides whether particular courses of action conform to it.

- The Islamic Study/Fatwah Committee issues religious edicts, such as an edict in 1998 telling Muslims to kill Americans.

- In the late 1990s, there was a publicly known Media Committee, which ran the now-defunct newspaper Nashrat al Akhbar (Newscast) and handled public relations.

- In 2005, al-Qaeda formed As-Sahab, a media production house, to supply its video and audio materials.

Command structure

When asked about the possibility of al-Qaeda's connection to the July 7, 2005 London bombings in 2005, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Ian Blair said: "Al-Qaeda is not an organization. Al-Qaeda is a way of working... but this has the hallmark of that approach... al-Qaeda clearly has the ability to provide training... to provide expertise... and I think that is what has occurred here."[63]

On August 13, 2005, however, The Independent newspaper, quoting police and MI5 investigations, reported that the July 7 bombers had acted independently of an al-Qaeda terror mastermind someplace abroad.[64]

What exactly al-Qaeda is, or was, remains in dispute. Certainly, it has been obliged to evolve and adapt in the aftermath of 9/11 and the launch of the 'war on terror'.

Nasser al-Bahri, who was Osama bin Laden's bodyguard for four years in the run-up to 9/11 gives a highly detailed description of how the group functioned at that time in his memoir.[65] He describes its formal administrative structure and vast arsenal, as well as day-to-day life as a member.

However, author and journalist Adam Curtis argues that the idea of al-Qaeda as a formal organization is primarily an American invention. Curtis contends the name "al-Qaeda" was first brought to the attention of the public in the 2001 trial of bin Laden and the four men accused of the 1998 US embassy bombings in East Africa:

The reality was that bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri had become the focus of a loose association of disillusioned Islamist militants who were attracted by the new strategy. But there was no organization. These were militants who mostly planned their own operations and looked to bin Laden for funding and assistance. He was not their commander. There is also no evidence that bin Laden used the term "al-Qaeda" to refer to the name of a group until after September 11 attacks, when he realized that this was the term the Americans had given it.[66]

As a matter of law, the US Department of Justice needed to show that bin Laden was the leader of a criminal organization in order to charge him in absentia under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, also known as the RICO statutes. The name of the organization and details of its structure were provided in the testimony of Jamal al-Fadl, who said he was a founding member of the group and a former employee of bin Laden.[67] Questions about the reliability of al-Fadl's testimony have been raised by a number of sources because of his history of dishonesty, and because he was delivering it as part of a plea bargain agreement after being convicted of conspiring to attack U.S. military establishments.[53][68] Sam Schmidt, one of his defense lawyers, said:

There were selective portions of al-Fadl's testimony that I believe was false, to help support the picture that he helped the Americans join together. I think he lied in a number of specific testimony about a unified image of what this organization was. It made al-Qaeda the new Mafia or the new Communists. It made them identifiable as a group and therefore made it easier to prosecute any person associated with al-Qaeda for any acts or statements made by bin Laden.[66]

Field operatives

The number of individuals in the group who have undergone proper military training, and are capable of commanding insurgent forces, is largely unknown. Documents captured in the raid on bin Laden compound in 2011, show that the core al-Qaeda membership in 2002 was 170.[69] In 2006, it was estimated that al-Qaeda had several thousand commanders embedded in 40 different countries.[70] As of 2009[update], it was believed that no more than 200–300 members were still active commanders.[71]

According to the award-winning 2004 BBC documentary The Power of Nightmares, al-Qaeda was so weakly linked together that it was hard to say it existed apart from bin Laden and a small clique of close associates. The lack of any significant numbers of convicted al-Qaeda members, despite a large number of arrests on terrorism charges, was cited by the documentary as a reason to doubt whether a widespread entity that met the description of al-Qaeda existed.[72]

Insurgent forces

According to Robert Cassidy, al-Qaeda controls two separate forces deployed alongside insurgents in Iraq and Pakistan. The first, numbering in the tens of thousands, was "organized, trained, and equipped as insurgent combat forces" in the Soviet-Afghan war.[70] It was made up primarily of foreign mujahideen from Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Many went on to fight in Bosnia and Somalia for global jihad. Another group, approximately 10,000 strong, live in Western states and have received rudimentary combat training.[70]

Other analysts have described al-Qaeda's rank and file as being "predominantly Arab," in its first years of operation, and now also includes "other peoples" as of 2007[update].[73] It has been estimated that 62% of al-Qaeda members have university education.[74]

Financing

Some financing for al-Qaeda in the 1990s came from the personal wealth of Osama bin Laden.[75] By 2001 Afghanistan had become politically complex and mired. With many financial sources for al-Qaeda, bin Laden's financing role may have become comparatively minor. Sources in 2001 could also have included Jamaa Al-Islamiyya and Islamic Jihad, both associated with Afghan-based Egyptians.[76] Other sources of income in 2001 included the heroin trade and donations from supporters in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and other Islamic countries.[75] A WikiLeaks released memo from the United States Secretary of State sent in 2009 asserted that the primary source of funding of Sunni terrorist groups worldwide was Saudi Arabia.[77]

Strategy

On March 11, 2005, Al-Quds Al-Arabi published extracts from Saif al-Adel's document "Al Qaeda's Strategy to the Year 2020".[78][79] Abdel Bari Atwan summarizes this strategy as comprising five stages to rid the Ummah from all forms of oppression:

- Provoke the United States and the West into invading a Muslim country by staging a massive attack or string of attacks on US soil that results in massive civilian casualties.

- Incite local resistance to occupying forces.

- Expand the conflict to neighboring countries, and engage the US and its allies in a long war of attrition.

- Convert al-Qaeda into an ideology and set of operating principles that can be loosely franchised in other countries without requiring direct command and control, and via these franchises incite attacks against the US and countries allied with the US until they withdraw from the conflict, as happened with the 2004 Madrid train bombings, but which did not have the same effect with the July 7, 2005 London bombings.

- The US economy will finally collapse by the year 2020, under the strain of multiple engagements in numerous places, making the worldwide economic system, which is dependent on the U.S., also collapse, leading to global political instability, which in turn leads to a global jihad led by al-Qaeda, and a Wahhabi Caliphate will then be installed across the world, following the collapse of the U.S. and the rest of the Western world countries.

Atwan also noted, regarding the collapse of the U.S., "If this sounds far-fetched, it is sobering to consider that this virtually describes the downfall of the Soviet Union."[78]

According to Fouad Hussein, a Jordanian journalist and author who has spent time in prison with Al-Zarqawi, Al Qaeda's strategy plan consists of 7 phases and is similar to the plan described in Al Qaeda's Strategy to the year 2020:[80]

- The Awakening. This phase was supposed to last from 2001 to 2003. The goal of the phase is to provoke the United States to attack a Muslim country by executing an attack on US soil that kills many civilians.

- Opening Eyes This phase was supposed to last from 2003 to 2006. The goal of this phase was to recruit young men to the cause and to transform the al-Qaeda group into a movement. Iraq was supposed to become the center of all operations with financial and military support for bases in other states.

- Arising and Standing up, was supposed to last from 2007 to 2010. In this phase, al-Qaeda wanted to execute additional attacks and focus their attention on Syria. Hussein believed that other countries in the Arabian Peninsula were also in danger.

- In the fourth phase, al-Qaeda expected a steady growth among their ranks and territories due to the declining power of the regimes in the Arabian Peninsula. The main focus of attack in this phase was supposed to be on oil suppliers and Cyberterrorism, targeting the US economy and military infrastructure.

- The fifth phase is the declaration of an Islamic Caliphate, which was projected between 2013 and 2016. In this phase, al-Qaeda expected the resistance from Israel to be heavily reduced.

- The sixth phase is described as the declaration of an "Islamic Army" and a "fight between believers and non-believers", also called "total confrontation".

- Definitive Victory, the seventh and last phase is projected to be completed by 2020. The world will be "beaten down" by the Islamic Army. According to the 7 phase strategy, the war isn't projected to last longer than 2 years.

Name

In Arabic, al-Qaeda has four syllables (al-qāʿidah, Arabic pronunciation: [ælˈqɑːʕɪdɐ] or [ælqɑːˈʕedæ]). However, since two of the Arabic consonants in the name (the voiceless uvular plosive [q] and the voiced pharyngeal fricative [ʕ]) are not phones found in the English language, the common naturalized English pronunciations include /ælˈkaɪdə/, /ælˈkeɪdə/ and /ˌælkɑːˈiːdə/. Al-Qaeda's name can also be transliterated as al-Qaida, al-Qa'ida, or el-Qaida.[81]

The name comes from the Arabic noun qā'idah, which means foundation or basis, and can also refer to a military base. The initial al- is the Arabic definite article the, hence the base.[82]

Bin Laden explained the origin of the term in a videotaped interview with Al Jazeera journalist Tayseer Alouni in October 2001:

The name 'al-Qaeda' was established a long time ago by mere chance. The late Abu Ebeida El-Banashiri established the training camps for our mujahedeen against Russia's terrorism. We used to call the training camp al-Qaeda. The name stayed.[83]

It has been argued that two documents seized from the Sarajevo office of the Benevolence International Foundation prove that the name was not simply adopted by the mujahid movement and that a group called al-Qaeda was established in August 1988. Both of these documents contain minutes of meetings held to establish a new military group, and contain the term "al-Qaeda".[84]

Former British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook wrote that the word al-Qaeda should be translated as "the database", and originally referred to the computer file of the thousands of mujahideen militants who were recruited and trained with CIA help to defeat the Russians.[85] In April 2002, the group assumed the name Qa'idat al-Jihad, which means "the base of Jihad". According to Diaa Rashwan, this was "apparently as a result of the merger of the overseas branch of Egypt's al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamist Jihad, or EIJ) group, led by Ayman al-Zawahiri, with the groups Bin Laden brought under his control after his return to Afghanistan in the mid-1990s."[86]

Ideology

| Part of a series on Islamism |

|---|

|

|

The radical Islamist movement in general and al-Qaeda in particular developed during the Islamic revival and Islamist movement of the last three decades of the 20th century, along with less extreme movements. The Afghan jihad against the pro-Soviet government (December 1979 to February 1989) developed the Salafist Jihadist movement of which Al-Qaeda was the most prominent example.[87]

Some have argued that "without the writings" of Islamic author and thinker Sayyid Qutb, "al-Qaeda would not have existed."[88] Qutb preached that because of the lack of sharia law, the Muslim world was no longer Muslim, having reverted to pre-Islamic ignorance known as jahiliyyah.

To restore Islam, he said a vanguard movement of righteous Muslims was needed to establish "true Islamic states", implement sharia, and rid the Muslim world of any non-Muslim influences, such as concepts like socialism and nationalism. Enemies of Islam in Qutb's view included "treacherous Orientalists"[89] and "world Jewry," who plotted "conspiracies" and "wicked[ly]" opposed Islam.

In the words of Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, a close college friend of bin Laden:

Islam is different from any other religion; it's a way of life. We [Khalifa and bin Laden] were trying to understand what Islam has to say about how we eat, who we marry, how we talk. We read Sayyid Qutb. He was the one who most affected our generation.[90]

Qutb had an even greater influence on bin Laden's mentor and another leading member of al-Qaeda,[91] Ayman al-Zawahiri. Zawahiri's uncle and maternal family patriarch, Mafouz Azzam, was Qutb's student, then protégé, then personal lawyer, and finally executor of his estate—one of the last people to see Qutb before his execution. "Young Ayman al-Zawahiri heard again and again from his beloved uncle Mahfouz about the purity of Qutb's character and the torment he had endured in prison."[92] Zawahiri paid homage to Qutb in his work Knights under the Prophet's Banner.[93]

One of the most powerful of Qutb's ideas was that many who said they were Muslims were not. Rather, they were apostates. That not only gave jihadists "a legal loophole around the prohibition of killing another Muslim," but made "it a religious obligation to execute" these self-professed Muslims. These alleged apostates included leaders of Muslim countries, since they failed to enforce sharia law.[94]

Religious compatibility

Abdel Bari Atwan writes that:

While the leadership's own theological platform is essentially Salafi, the organization's umbrella is sufficiently wide to encompass various schools of thought and political leanings. Al-Qaeda counts among its members and supporters people associated with Wahhabism, Shafi'ism, Malikism, and Hanafism. There are even some whose beliefs and practices are directly at odds with Salafism, such as Yunis Khalis, one of the leaders of the Afghan mujahedin. He is a mystic who visits tombs of saints and seeks their blessings—practices inimical to bin Laden's Wahhabi-Salafi school of thought. The only exception to this pan-Islamic policy is Shi'ism. Al-Qaeda seems implacably opposed to it, as it holds Shi'ism to be heresy. In Iraq it has openly declared war on the Badr Brigades, who have fully cooperated with the US, and now considers even Shi'i civilians to be legitimate targets for acts of violence.[95]

History

This section may contain information not important or relevant to the article's subject. (May 2011) |

The Guardian has described five distinct phases in the development of al-Qaeda: beginnings in the late 1980s, a "wilderness" period in 1990–96, its "heyday" in 1996–2001, a network period from 2001 to 2005, and a period of fragmentation from 2005 to today.[96]

Jihad in Afghanistan

The origins of al-Qaeda as a network inspiring terrorism around the world and training operatives can be traced to the Soviet War in Afghanistan (December 1979 – February 1989).[30] The US viewed the conflict in Afghanistan, with the Afghan Marxists and allied Soviet troops on one side and the native Afghan mujahideen, some of whom were radical Islamic militants, on the other, as a blatant case of Soviet expansionism and aggression. A CIA program called Operation Cyclone channeled funds through Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency to the Afghan Mujahideen who were fighting the Soviet occupation.[97]

At the same time, a growing number of Arab mujahideen joined the jihad against the Afghan Marxist regime, facilitated by international Muslim organizations, particularly the Maktab al-Khidamat,[98] which was funded by the Saudi Arabia government as well as by individual Muslims (particularly Saudi businessmen who were approached by bin Laden). Together, these sources donated some $600 million a year to jihad.[99][page needed]

In 1984, Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), or the "Services Office", a Muslim organization founded to raise and channel funds and recruit foreign mujahideen for the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan, was established in Peshawar, Pakistan, by bin Laden and Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, a Palestinian Islamic scholar and member of the Muslim Brotherhood. MAK organized guest houses in Peshawar, near the Afghan border, and gathered supplies for the construction of paramilitary training camps to prepare foreign recruits for the Afghan war front. Bin Laden became a "major financier" of the mujahideen, spending his own money and using his connections with "the Saudi royal family and the petro-billionaires of the Gulf" to influence public opinion about the war and raise additional funds.[100]

From 1986, MAK began to set up a network of recruiting offices in the US, the hub of which was the Al Kifah Refugee Center at the Farouq Mosque on Brooklyn's Atlantic Avenue. Among notable figures at the Brooklyn center were "double agent" Ali Mohamed, whom FBI special agent Jack Cloonan called "bin Laden's first trainer,"[101] and "Blind Sheikh" Omar Abdel-Rahman, a leading recruiter of mujahideen for Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda evolved from MAK.

Azzam and bin Laden began to establish camps in Afghanistan in 1987.[102]

US government financial support for the Afghan Islamic militants was substantial. Aid to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, an Afghan mujahideen leader and founder and leader of the Hezb-e Islami radical Islamic militant faction, alone amounted "by the most conservative estimates" to $600 million. Later, in the early 1990s, after the US had withdrawn support, Hekmatyar "worked closely" with bin Laden.[103] In addition to receiving hundreds of millions of dollars in American aid, Hekmatyar was the recipient of the lion's share of Saudi aid.[104] There is evidence that the CIA supported Hekmatyar's drug trade activities by giving him immunity for his opium trafficking, which financed the operation of his militant faction.[105]

MAK and foreign mujahideen volunteers, or "Afghan Arabs," did not play a major role in the war. While over 250,000 Afghan mujahideen fought the Soviets and the communist Afghan government, it is estimated that were never more than 2,000 foreign mujahideen in the field at any one time.[106] Nonetheless, foreign mujahideen volunteers came from 43 countries, and the total number that participated in the Afghan movement between 1982 and 1992 is reported to have been 35,000.[107] Bin Laden played a central role in organizing training camps for the foreign Muslim volunteers.[108][109]

The Soviet Union finally withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989. To the surprise of many, Mohammad Najibullah's communist Afghan government hung on for three more years, before being overrun by elements of the mujahideen. With mujahideen leaders unable to agree on a structure for governance, chaos ensued, with constantly reorganizing alliances fighting for control of ill-defined territories, leaving the country devastated.

Expanding operations

The correlation between the words and deeds of bin Laden, his lieutenants, and their allies was close to perfect—if they said they were going to do something, they were much more than likely to try to do it. Their record in this regard puts Western leaders to shame.

— Michael Scheuer, CIA Station Chief[110]

Toward the end of the Soviet military mission in Afghanistan, some mujahideen wanted to expand their operations to include Islamist struggles in other parts of the world, such as Israel and Kashmir. A number of overlapping and interrelated organizations were formed, to further those aspirations.

One of these was the organization that would eventually be called al-Qaeda, formed by bin Laden with an initial meeting held on August 11, 1988.[111][112]

Notes of a meeting of bin Laden and others on August 20, 1988, indicate al-Qaeda was a formal group by that time: "basically an organized Islamic faction, its goal is to lift the word of God, to make His religion victorious." A list of requirements for membership itemized the following: listening ability, good manners, obedience, and making a pledge (bayat) to follow one's superiors.[113]

In his memoir, bin Laden's former bodyguard, Nasser al-Bahri, gives the only publicly available description of the ritual of giving bayat when he swore his allegiance to the al-Qaeda chief.[114]

According to Wright, the group's real name wasn't used in public pronouncements because "its existence was still a closely held secret."[115] His research suggests that al-Qaeda was formed at an August 11, 1988, meeting between "several senior leaders" of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Abdullah Azzam, and bin Laden, where it was agreed to join bin Laden's money with the expertise of the Islamic Jihad organization and take up the jihadist cause elsewhere after the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan.[116]

Bin Laden wished to establish non-military operations in other parts of the world; Azzam, in contrast, wanted to remain focused on military campaigns. After Azzam was assassinated in 1989, the MAK split, with a significant number joining bin Laden's organization.

In November 1989, Ali Mohamed, a former special forces Sergeant stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, left military service and moved to California. He traveled to Afghanistan and Pakistan and became "deeply involved with bin Laden's plans."[117]

A year later, on November 8, 1990, the FBI raided the New Jersey home of Ali Mohammed's associate El Sayyid Nosair, discovering a great deal of evidence of terrorist plots, including plans to blow up New York City skyscrapers.[118] Nosair was eventually convicted in connection to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. In 1991, Ali Mohammed is said to have helped orchestrate bin Laden's relocation to Sudan.[119]

Gulf War and the start of US enmity

Following the Soviet Union's withdrawal from Afghanistan in February 1989, bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia. The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 had put the Kingdom and its ruling House of Saud at risk. The world's most valuable oil fields were within easy striking distance of Iraqi forces in Kuwait, and Saddam's call to pan-Arab/Islamism could potentially rally internal dissent.

In the face of a seemingly massive Iraqi military presence, Saudi Arabia's own forces were well armed but far outnumbered. Bin Laden offered the services of his mujahideen to King Fahd to protect Saudi Arabia from the Iraqi army. The Saudi monarch refused bin Laden's offer, opting instead to allow US and allied forces to deploy troops into Saudi territory.[120]

The deployment angered bin Laden, as he believed the presence of foreign troops in the "land of the two mosques" (Mecca and Medina) profaned sacred soil. After speaking publicly against the Saudi government for harboring American troops, he was banished and forced to live in exile in Sudan.

Sudan

From around 1992 to 1996, al-Qaeda and bin Laden based themselves in Sudan at the invitation of Islamist theoretician Hassan al-Turabi. The move followed an Islamist coup d'état in Sudan, led by Colonel Omar al-Bashir, who professed a commitment to reordering Muslim political values. During this time, bin Laden assisted the Sudanese government, bought or set up various business enterprises, and established camps where insurgents trained.

A key turning point for bin Laden, further pitting him against the Sauds, occurred in 1993 when Saudi Arabia gave support for the Oslo Accords, which set a path for peace between Israel and Palestinians.[121]

Zawahiri and the EIJ, who served as the core of al-Qaeda but also engaged in separate operations against the Egyptian government, had bad luck in Sudan. In 1993, a young schoolgirl was killed in an unsuccessful EIJ attempt on the life of the Egyptian prime minister, Atef Sedki. Egyptian public opinion turned against Islamist bombings, and the police arrested 280 of al-Jihad's members and executed 6.[122]

Due to bin Laden's continuous verbal assault on King Fahd of Saudi Arabia, on March 5, 1994 Fahd sent an emissary to Sudan demanding bin Laden's passport; bin Laden's Saudi citizenship was also revoked. His family was persuaded to cut off his monthly stipend, $7 million ($14,400,000 today) a year, and his Saudi assets were frozen.[123][124] His family publicly disowned him. There is controversy over whether and to what extent he continued to garner support from members of his family and/or the Saudi government.[125]

In June 1995, an even more ill-fated attempt to assassinate Egyptian president Mubarak led to the expulsion of EIJ, and in May 1996, of bin Laden, by the Sudanese government.

According to Pakistani-American businessman Mansoor Ijaz, the Sudanese government offered the Clinton Administration numerous opportunities to arrest bin Laden. Those opportunities were met positively by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, but spurned when Susan Rice and counter-terrorism czar Richard Clarke persuaded National Security Advisor Sandy Berger to overrule Albright. Ijaz's claims appeared in numerous Op-Ed pieces, including one in the Los Angeles Times[126] and one in The Washington Post co-written with former Ambassador to Sudan Timothy M. Carney.[127] Similar allegations have been made by Vanity Fair contributing editor David Rose,[128] and Richard Miniter, author of Losing bin Laden, in a November 2003 interview with World.[129]

Several sources dispute Ijaz's claim, including the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks on the US (the 9/11 Commission), which concluded in part:

Sudan's minister of defense, Fatih Erwa, has claimed that Sudan offered to hand Bin Ladin over to the US The Commission has found no credible evidence that this was so. Ambassador Carney had instructions only to push the Sudanese to expel Bin Ladin. Ambassador Carney had no legal basis to ask for more from the Sudanese since, at the time, there was no indictment out-standing.[130]

Refuge in Afghanistan

After the Soviet withdrawal, Afghanistan was effectively ungoverned for seven years and plagued by constant infighting between former allies and various mujahideen groups.

Throughout the 1990s, a new force began to emerge. The origins of the Taliban (literally "students") lay in the children of Afghanistan, many of them orphaned by the war, and many of whom had been educated in the rapidly expanding network of Islamic schools (madrassas) either in Kandahar or in the refugee camps on the Afghan-Pakistani border.

According to Ahmed Rashid, five leaders of the Taliban were graduates of Darul Uloom Haqqania, a madrassa in the small town of Akora Khattak.[131] The town is situated near Peshawar in Pakistan, but largely attended by Afghan refugees.[131] This institution reflected Salafi beliefs in its teachings, and much of its funding came from private donations from wealthy Arabs. Bin Laden's contacts were still laundering most of these donations, using "unscrupulous" Islamic banks to transfer the money to an "array" of charities which serve as front groups for al-Qaeda, or transporting cash-filled suitcases straight into Pakistan.[132] Another four of the Taliban's leaders attended a similarly funded and influenced madrassa in Kandahar.

Many of the mujahideen who later joined the Taliban fought alongside Afghan warlord Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi's Harkat i Inqilabi group at the time of the Russian invasion. This group also enjoyed the loyalty of most Afghan Arab fighters.

The continuing internecine strife between various factions, and accompanying lawlessness following the Soviet withdrawal, enabled the growing and well-disciplined Taliban to expand their control over territory in Afghanistan, and it came to establish an enclave which it called the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. In 1994, it captured the regional center of Kandahar, and after making rapid territorial gains thereafter, conquered the capital city Kabul in September 1996.

After the Sudanese made it clear, in May 1996, that bin Laden would never be welcome to return,[clarification needed] Taliban-controlled Afghanistan—with previously established connections between the groups, administered with a shared militancy,[133] and largely isolated from American political influence and military power—provided a perfect location for al-Qaeda to relocate its headquarters. Al-Qaeda enjoyed the Taliban's protection and a measure of legitimacy as part of their Ministry of Defense,[citation needed] although only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan.

While in Afghanistan, the Taliban government tasked al-Qaeda with the training of Brigade 055, an elite part of the Taliban's army from 1997–2001. The Brigade was made up of mostly foreign fighters, many veterans from the Soviet Invasion, and all under the same basic ideology of the mujahideen. In November 2001, as Operation Enduring Freedom had toppled the Taliban government, many Brigade 055 fighters were captured or killed, and those that survived were thought to head into Pakistan along with bin Laden.[134]

By the end of 2008, some sources reported that the Taliban had severed any remaining ties with al-Qaeda,[135] while others cast doubt on this.[136] According to senior US military intelligence officials, there were fewer than 100 members of al-Qaeda remaining in Afghanistan in 2009.[137]

Call for global Salafi jihadism

Around 1994, the Salafi groups waging Salafi jihadism in Bosnia entered into a seemingly irreversible decline. As they grew less and less aggressive, groups such as EIJ began to drift away from the Salafi cause in Europe. Al-Qaeda stepped in and assumed control of around 80% of the terrorist cells in Bosnia in late 1995.

At the same time, al-Qaeda ideologues instructed the network's recruiters to look for Jihadi international Muslims who believed that extremist-jihad must be fought on a global level. The concept of a "global Salafi jihad" had been around since at least the early 1980s. Several groups had formed for the explicit purpose of driving non-Muslims out of every Muslim land at the same time and with maximum carnage. This was, however, a fundamentally defensive strategy.[clarification needed]

Al-Qaeda sought to open the "offensive phase" of the global Salafi jihad.[138] Bosnian Islamists in 2006 called for "solidarity with Islamic causes around the world", supporting the insurgents in Kashmir and Iraq as well as the groups fighting for a Palestinian state.[139]

Fatwas

In 1996, al-Qaeda announced its jihad to expel foreign troops and interests from what they considered Islamic lands. Bin Laden issued a fatwa (binding religious edict),[140] which amounted to a public declaration of war against the US and its allies, and began to refocus al-Qaeda's resources on large-scale, propagandist strikes.

On February 23, 1998, bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, a leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, along with three other Islamist leaders, co-signed and issued a fatwa calling on Muslims to kill Americans and their allies where they can, when they can.[141] Under the banner of the World Islamic Front for Combat Against the Jews and Crusaders, they declared:

[T]he ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it, in order to liberate the al-Aqsa Mosque [in Jerusalem] and the holy mosque [in Mecca] from their grip, and in order for their armies to move out of all the lands of Islam, defeated and unable to threaten any Muslim. This is in accordance with the words of Almighty Allah, 'and fight the pagans all together as they fight you all together,' and 'fight them until there is no more tumult or oppression, and there prevail justice and faith in Allah'.[142]

Neither bin Laden nor al-Zawahiri possessed the traditional Islamic scholarly qualifications to issue a fatwa. However, they rejected the authority of the contemporary ulema (which they saw as the paid servants of jahiliyya rulers), and took it upon themselves.[143][unreliable source?] Former Russian FSB agent Alexander Litvinenko, who was later killed, said that the FSB trained al-Zawahiri in a camp in Dagestan eight months before the 1998 fatwa.[144][145]

Iraq

Al-Qaeda is Sunni, and often attacked the Iraqi Shia majority in an attempt to incite sectarian violence and greater chaos in the country.[146] Al-Zarqawi purportedly declared an all-out war on Shiites[147] while claiming responsibility for Shiite mosque bombings.[148] The same month, a statement claiming to be by AQI rejected as "fake" a letter allegedly written by al-Zawahiri, in which he appears to question the insurgents' tactic of indiscriminately attacking Shiites in Iraq.[149] In a December 2007 video, al-Zawahiri defended the Islamic State in Iraq, but distanced himself from the attacks against civilians committed by "hypocrites and traitors existing among the ranks".[150]

US and Iraqi officials accused AQI of trying to slide Iraq into a full-scale civil war between Iraq's majority Shiites and minority Sunni Arabs, with an orchestrated campaign of civilian massacres and a number of provocative attacks against high-profile religious targets.[151] With attacks such as the 2003 Imam Ali Mosque bombing, the 2004 Day of Ashura and Karbala and Najaf bombings, the 2006 first al-Askari Mosque bombing in Samarra, the deadly single-day series of bombings in which at least 215 people were killed in Baghdad's Shiite district of Sadr City, and the second al-Askari bombing in 2007, they provoked Shiite militias to unleash a wave of retaliatory attacks, resulting in death squad-style killings and spiraling further sectarian violence which escalated in 2006 and brought Iraq to the brink of violent anarchy in 2007.[152] In 2008, sectarian bombings blamed on al-Qaeda in Iraq killed at least 42 people at the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala in March, and at least 51 people at a bus stop in Baghdad in June.

In February 2014, after a prolonged dispute with al-Qaeda in Iraq's successor organisation, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), al-Qaeda publicly announced it was cutting all ties with the group, reportedly for its brutality and "notorious intractability".[153]

Somalia and Yemen

In Somalia, al-Qaeda agents had been collaborating closely with its Somali wing, which was created from the al-Shabaab group. In February 2012, al-Shabaab officially joined al-Qaeda, declaring loyalty in a joint video.[154] The Somalian al-Qaeda actively recruit children for suicide-bomber training, and export young people to participate in military actions against Americans at the AfPak border.[155]

The percentage of terrorist attacks in the West originating from the Afghanistan-Pakistan (AfPak) border declined considerably from almost 100% to 75% in 2007, and to 50% in 2010, as al-Qaeda shifted to Somalia and Yemen.[156] While al-Qaeda leaders are hiding in the tribal areas along the AfPak border, the middle-tier of the movement display heightened activity in Somalia and Yemen. "We know that South Asia is no longer their primary base," a US defense agency source said. "They are looking for a hide-out in other parts of the world, and continue to expand their organization."

In January 2009, al-Qaeda's division in Saudi Arabia merged with its Yemeni wing to form al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[157] Centered in Yemen, the group takes advantage of the country's poor economy, demography and domestic security. In August 2009, they made the first assassination attempt against a member of the Saudi royal dynasty in decades. President Obama asked his Yemen counterpart Ali Abdullah Saleh to ensure closer cooperation with the US in the struggle against the growing activity of al-Qaeda in Yemen, and promised to send additional aid. Because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US was unable to pay sufficient attention to Somalia and Yemen, which could cause problems in the near future.[158] In December 2011, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta said that the US operations against al-Qaeda "are now concentrating on key groups in Yemen, Somalia and North Africa."[159] Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula claimed responsibility for the 2009 bombing attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253 by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab.[160] The group released photos of Abdulmutallab smiling in a white shirt and white Islamic skullcap, with the al-Qaeda in Arabian Peninsula banner in the background.

As the Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen escalated in July 2015, The Guardian wrote: "As another 50 civilians die in the forgotten war, only Isis and al-Qaida are gaining from a conflict tearing Yemen apart and leaving 20 million people in need of aid."[161]

United States operations

In December 1998, the Director of the CIA Counterterrorism Center reported to the president that al-Qaeda was preparing for attacks in the USA, including the training of personnel to hijack aircraft.[162] On September 11, 2001, al-Qaeda attacked the United States, hijacking four airliners within the country and deliberately crashing two into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, and the third into the western side of the Pentagon in Arlington County, Virginia. The fourth, however, failed to reach its intended target – either the United States Capitol or the White House, both located in Washington, D.C. – due to the rebellion by the passengers to retake the airliner, and instead crashed into the field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania.[163] In total, the attackers killed 2,977 victims, including 2,507 civilians, 72 law enforcement officers, 343 firefighters, and 55 military personnel.[164]

U.S. officials called Anwar al-Awlaki an "example of al-Qaeda reach into" the U.S. in 2008 after probes into his ties to the September 11 attacks hijackers. A former FBI agent identifies Awlaki as a known "senior recruiter for al-Qaeda", and a spiritual motivator.[165] Awlaki's sermons in the U.S. were attended by three of the 9/11 hijackers, as well as accused Fort Hood shooter Nidal Malik Hasan. U.S. intelligence intercepted emails from Hasan to Awlaki between December 2008 and early 2009. On his website, Awlaki has praised Hasan's actions in the Fort Hood shooting.[166]

An unnamed official claimed there was good reason to believe Awlaki "has been involved in very serious terrorist activities since leaving the U.S. [after 9/11], including plotting attacks against America and our allies."[167]

US President Barack Obama approved the targeted killing of al-Awlaki by April 2010, making al-Awlaki the first US citizen ever placed on the CIA target list. That required the consent of the U.S. National Security Council, and officials said it was appropriate for an individual who posed an imminent danger to national security.[168][169][170] In May 2010, Faisal Shahzad, who pleaded guilty to the 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt, told interrogators he was "inspired by" al-Awlaki, and sources said Shahzad had made contact with al-Awlaki over the internet.[171][172][173] Representative Jane Harman called him "terrorist number one", and Investor's Business Daily called him "the world's most dangerous man".[174][175] In July 2010, the US Treasury Department added him to its list of Specially Designated Global Terrorists, and the UN added him to its list of individuals associated with al-Qaeda.[176] In August 2010, al-Awlaki's father initiated a lawsuit against the U.S. government with the American Civil Liberties Union, challenging its order to kill al-Awlaki.[177] In October 2010, U.S. and U.K. officials linked al-Awlaki to the 2010 cargo plane bomb plot.[178] In September 2011, he was killed in a targeted killing drone attack in Yemen.[179] It was reported on March 16, 2012 that Osama bin Laden plotted to kill United States President Barack Obama.[180]

Death of Osama bin Laden

On May 1, 2011 in Washington, D.C. (May 2, Pakistan Standard Time), U.S. President Barack Obama announced that Osama bin Laden had been killed by "a small team of Americans" acting under Obama's direct orders, in a covert operation in Abbottabad, Pakistan,[181][182] about 50 km (31 mi) north of Islamabad.[183] According to U.S. officials a team of 20–25 US Navy SEALs under the command of the Joint Special Operations Command and working with the CIA stormed bin Laden's compound in two helicopters. Bin Laden and those with him were killed during a firefight in which U.S. forces experienced no injuries or casualties.[184] According to one US official the attack was carried out without the knowledge or consent of the Pakistani authorities.[185] In Pakistan some people were reported to be shocked at the unauthorized incursion by US armed forces.[186] The site is a few miles from the Pakistan Military Academy in Kakul.[187] In his broadcast announcement President Obama said that U.S. forces "took care to avoid civilian casualties."[188] Details soon emerged that three men and a woman were killed along with bin Laden, the woman being killed when she was "used as a shield by a male combatant".[185] DNA from bin Laden's body, compared with DNA samples on record from his dead sister,[189] confirmed bin Laden's identity.[190] The body was recovered by the US military and was in its custody[182] until, according to one US official, his body was buried at sea according to Islamic traditions.[183][191] One U.S. official stated that "finding a country willing to accept the remains of the world's most wanted terrorist would have been difficult."[192] U.S State Department issued a "Worldwide caution" for Americans following bin Laden's death and U.S Diplomatic facilities everywhere were placed on high alert, a senior U.S official said.[193] Crowds gathered outside the White House and in New York City's Times Square to celebrate bin Laden's death.[194]

Syria

In 2003, President Bashar al-Assad revealed in an interview with a Kuwaiti newspaper that he doubted al-Qaeda even existed. He was quoted as saying, "Is there really an entity called al-Qaeda? Was it in Afghanistan? Does it exist now?" He went on further to remark about bin Laden commenting, he "cannot talk on the phone or use the Internet, but he can direct communications to the four corners of the world? This is illogical."[196]

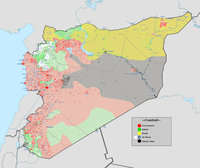

Following the mass protests that took place later in 2011 demanding the resignation of al-Assad, al-Qaeda affiliated groups and Sunni sympathizers soon began to constitute the most effective fighting force in the Syrian opposition.[197] Until then, al-Qaeda's presence in Syria was not worth mentioning, but its growth thereafter was rapid.[198] Groups such as the al-Nusra Front and the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS; sometimes ISIL) have recruited many foreign Mujahideen to train and fight in what has gradually become a highly sectarian war.[199][200] Ideologically, the Syrian Civil War has served the interests of al-Qaeda as it pits a mainly Sunni opposition against a Shia backed Alawite regime. Viewing Shia Islam as heretical, al-Qaeda and other fundamentalist Sunni militant groups have invested heavily in the civil conflict, actively backing and supporting the Syrian Opposition despite its clashes with moderate opposition groups such as the Free Syrian Army (FSA).[201][202]

On February 2, 2014, al-Qaeda distanced itself from ISIS and its actions in Syria,[203] but ISIS and al-Qaeda-linked al-Nusra Front[204] are still able to occasionally cooperate with each other when they fight against the Syrian government.[205][206][207] The Saudi/Turkish-backed[208] al-Nusra launched many attacks and bombings, mostly against targets affiliated with or supportive of the Syrian government.[209] In October 2015, Russian air strikes targeted positions held by al-Nusra Front.[210][211]

India

In September 2014 al-Zawahiri announced al-Qaeda was establishing a front in India to "wage jihad against its enemies, to liberate its land, to restore its sovereignty, and to revive its Caliphate." He nominated India as a beachhead for regional jihad taking in neighboring countries such as Myanmar and Bangladesh. The motivation for the video was questioned in some quarters where it was seen the militant group was struggling to remain relevant in light of the emerging prominence of ISIS.[212] Reaction amongst Muslims in India to the formation of the new wing, to be known as "Qaedat al-Jihad fi'shibhi al-qarrat al-Hindiya" or al-Qaida in the Indian Subcontinent [AQIS], was one of fury. Leaders of several Indian Muslim organizations rejected al-Zawahiri's pronouncement, saying they could see no good coming from it, and viewed it as a threat to Muslim youth in the country.[213]

US intelligence analyst accused the Pakistan military of 'stage-managing' the terror outfit's latest advance into India. Bruce Riedel, a former CIA analyst and National Security Council official for South Asia, also said that Pakistan should be warned that it will be placed on the list of State Sponsors of Terrorism. Riedel also said that "Zawahiri made the tape in his hideout in Pakistan, no doubt, and many Indians suspect the ISI (Inter Services Intelligence) is helping to protect him," he wrote.[214][215][216]

Attacks

1. The Pentagon, US – September 11, 2001

2. World Trade Center, US – September 11, 2001

3. Istanbul, Turkey – November 15, 2003; November 20, 2003

4. Aden, Yemen – October 12, 2000

5. Nairobi, Kenya – August 7, 1998

6. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania – August 7, 1998

Al-Qaeda has carried out a total of six major terrorist attacks, four of them in its jihad against America. In each case the leadership planned the attack years in advance, arranging for the shipment of weapons and explosives and using its privatized businesses to provide operatives with safehouses and false identities.

Al-Qaeda usually does not disburse funds for attacks, and very rarely makes wire transfers.[217]

1992

On December 29, 1992, al-Qaeda's first terrorist attack took place as two bombs were detonated in Aden, Yemen. The first target was the Movenpick Hotel and the second was the parking lot of the Goldmohur Hotel.

The bombings were an attempt to eliminate American soldiers on their way to Somalia to take part in the international famine relief effort, Operation Restore Hope. Internally, al-Qaeda considered the bombing a victory that frightened the Americans away, but in the US, the attack was barely noticed.

No Americans were killed because the soldiers were staying in a different hotel altogether, and they went on to Somalia as scheduled. However, two people were killed in the bombing, an Australian tourist and a Yemeni hotel worker. Seven others, mostly Yemenis, were severely injured.[218] Two fatwas are said to have been appointed by the most theologically knowledgeable of al-Qaeda's members, Mamdouh Mahmud Salim, to justify the killings according to Islamic law. Salim referred to a famous fatwa appointed by Ibn Taymiyyah, a 13th-century scholar much admired by Wahhabis, which sanctioned resistance by any means during the Mongol invasions.[219][unreliable source?]

1993 World Trade Center bombing

On February 26, 1993, Ramzi Yousef detonated a truck bomb inside a parking garage of Tower One of the World Trade Center in New York City. His hope was to destroy the foundation of Tower One, knocking it into Tower Two, and resulting in the collapse of the towers, with the goal of causing the deaths of tens of thousands of people. The towers shook and swayed but the complex held and he succeeded in killing only six civilians, injuring 919 others (including an EMS worker), 88 firefighters, and 35 police officers, and causing nearly $300 million in property damage.[220]

After the attack, Yousef fled to Pakistan and later moved to Manila. There he began developing the Bojinka plot plans to implode a dozen American airliners simultaneously, to assassinate Pope John Paul II and President Bill Clinton, and to crash a private plane into CIA headquarters. He was later captured in Pakistan.[220]

None of the U.S. government's indictments against bin Laden have suggested that he had any connection with this bombing, but Ramzi Yousef is known to have attended a terrorist training camp in Afghanistan. After his capture, Yousef declared that his primary justification for the attack was to punish the U.S. for its support for the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories and made no mention of any religious motivations.[221] A follow-up attack was planned by Omar Abdel-Rahman – the New York City landmark bomb plot. However, the plot was foiled by the authorities.

Late 1990s

In 1996, bin Laden personally engineered a plot to assassinate Clinton while the president was in Manila for the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. However, intelligence agents intercepted a message just minutes before the motorcade was to leave, and alerted the U.S. Secret Service. Agents later discovered a bomb planted under a bridge.[222]

On August 7, 1998, al-Qaeda bombed the U.S. embassies in East Africa, killing 224 people, including 12 Americans. In retaliation, a barrage of cruise missiles launched by the U.S. military devastated an al-Qaeda base in Khost, Afghanistan, but the network's capacity was unharmed. In late 1999/2000, Al-Qaeda planned attacks to coincide with the millennium, masterminded by Abu Zubaydah and involving Abu Qatada, which would include the bombing Christian holy sites in Jordan, the bombing of Los Angeles International Airport by Ahmed Ressam, and the bombing of the USS The Sullivans (DDG-68).

On October 12, 2000, al-Qaeda militants in Yemen bombed the missile destroyer USS Cole in a suicide attack, killing 17 U.S. servicemen and damaging the vessel while it lay offshore. Inspired by the success of such a brazen attack, al-Qaeda's command core began to prepare for an attack on the U.S. itself.

September 11 attacks

The September 11, 2001 attacks were the most devastating terrorist acts in American history, killing 2,977 victims, including 2,507 civilians, 72 law enforcement officers, 343 firefighters, and 55 military personnel. Two commercial airliners were deliberately flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center, a third into the Pentagon, and a fourth, originally intended to target either the United States Capitol or the White House, crashed in a field in Stonycreek Township near Shanksville, Pennsylvania. It was also the deadliest foreign attack on American soil since the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

The attacks were conducted by al-Qaeda, acting in accord with the 1998 fatwa issued against the U.S. and its allies by persons under the command of bin Laden, al-Zawahiri, and others.[223] Evidence points to suicide squads led by al-Qaeda military commander Mohamed Atta as the culprits of the attacks, with bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and Hambali as the key planners and part of the political and military command.

Messages issued by bin Laden after September 11, 2001, praised the attacks, and explained their motivation while denying any involvement.[224] Bin Laden legitimized the attacks by identifying grievances felt by both mainstream and Islamist Muslims, such as the general perception that the U.S. was actively oppressing Muslims.[225]

Bin Laden asserted that America was massacring Muslims in "Palestine, Chechnya, Kashmir and Iraq" and that Muslims should retain the "right to attack in reprisal." He also claimed the 9/11 attacks were not targeted at people, but "America's icons of military and economic power," despite the fact he planned to attack in the morning where most of the people in the intended targets were present and thus generating massive amount of human casualties.[226]

Evidence has since come to light that the original targets for the attack may have been nuclear power stations on the east coast of the U.S. The targets were later altered by al-Qaeda, as it was feared that such an attack "might get out of hand".[227][228]

Designation as terrorist group

Al-Qaeda is deemed a designated terrorist group by the following countries and international organizations:

- Australia[229]

- Brazil[230]

- Canada[231]

- European Union[232]

- France[233]

- India[234]

- Ireland (Republic of)[235]

- Israel[236][237]

- Japan[238]

- NATO[239][240]

- Netherlands[241]

- New Zealand[242]

- Russia[243]

- South Korea[244]

- Sweden[245]

- Switzerland[246]

- Turkey designated Al-Qaeda's Turkish branch[247]

- United Kingdom[248]

United Nations Security Council[249]

United Nations Security Council[249]- United States[250]

War on Terror

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, the US government responded militarily, and began to prepare its armed forces to overthrow the Taliban regime it believed was harboring al-Qaeda. Before the US attacked, it offered Taliban leader Mullah Omar a chance to surrender bin Laden and his top associates. The first forces to be inserted into Afghanistan were Paramilitary Officers from the CIA's elite Special Activities Division (SAD).

The Taliban offered to turn over bin Laden to a neutral country for trial if the US would provide evidence of bin Laden's complicity in the attacks. US President George W. Bush responded by saying: "We know he's guilty. Turn him over",[251] and British Prime Minister Tony Blair warned the Taliban regime: "Surrender bin Laden, or surrender power".[252]

Soon thereafter the US and its allies invaded Afghanistan, and together with the Afghan Northern Alliance removed the Taliban government in the war in Afghanistan.

As a result of the US using its special forces and providing air support for the Northern Alliance ground forces, both Taliban and al-Qaeda training camps were destroyed, and much of the operating structure of al-Qaeda is believed to have been disrupted. After being driven from their key positions in the Tora Bora area of Afghanistan, many al-Qaeda fighters tried to regroup in the rugged Gardez region of the nation.

Again, under the cover of intense aerial bombardment, US infantry and local Afghan forces attacked, shattering the al-Qaeda position and killing or capturing many of the militants. By early 2002, al-Qaeda had been dealt a serious blow to its operational capacity, and the Afghan invasion appeared an initial success. Nevertheless, a significant Taliban insurgency remains in Afghanistan, and al-Qaeda's top two leaders, bin Laden and al-Zawahiri, evaded capture.

Debate raged about the exact nature of al-Qaeda's role in the 9/11 attacks, and after the US invasion began, the US State Department also released a videotape showing bin Laden speaking with a small group of associates somewhere in Afghanistan shortly before the Taliban was removed from power.[253] Although its authenticity has been questioned by a couple of people,[254] the tape definitively implicates bin Laden and al-Qaeda in the September 11 attacks and was aired on many television channels all over the world, with an accompanying English translation provided by the U.S. Defense Department.[255]

In September 2004, the US government 9/11 Commission investigating the September 11 attacks officially concluded that the attacks were conceived and implemented by al-Qaeda operatives.[256] In October 2004, bin Laden appeared to claim responsibility for the attacks in a videotape released through Al Jazeera, saying he was inspired by Israeli attacks on high-rises in the 1982 invasion of Lebanon: "As I looked at those demolished towers in Lebanon, it entered my mind that we should punish the oppressor in kind and that we should destroy towers in America in order that they taste some of what we tasted and so that they be deterred from killing our women and children."[257]

By the end of 2004, the U.S. government proclaimed that two-thirds of the most senior al-Qaeda figures from 2001 had been captured and interrogated by the CIA: Abu Zubaydah, Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri in 2002;[258] Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in 2003; and Saif al Islam el Masry in 2004.[citation needed] Mohammed Atef and several others were killed. The West was criticised for not being able to comprehend or deal with Al-Qaida despite more than a decade of the war. This also meant no progress has been made in global state security.[259]

Activities

Africa

Al-Qaeda involvement in Africa has included a number of bombing attacks in North Africa, as well as supporting parties in civil wars in Eritrea and Somalia. From 1991 to 1996, bin Laden and other al-Qaeda leaders were based in Sudan.

Islamist rebels in the Sahara calling themselves al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb have stepped up their violence in recent years.[261] French officials say the rebels have no real links to the al-Qaeda leadership, but this is a matter of some dispute in the international press and amongst security analysts. It seems likely that bin Laden approved the group's name in late 2006, and the rebels "took on the al Qaeda franchise label", almost a year before the violence began to escalate.[262]

In Mali, the Ansar Dine faction was also reported as an ally of Al-Qaeda in 2013.[263] The Ansar al Dine faction aligned themselves with the AQIM.[264]

Following the Libyan Civil War, the removal of Gaddafi and the ensuing period of post-civil war violence in Libya allowed various Islamist militant groups affiliated with Al-Qaeda to expand their operations in the region.[265] The 2012 Benghazi attack, which resulted in the death of US Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens and 3 other Americans, is suspected of having been carried out by various Jihadist networks, such as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, Ansar al-Sharia and several other Al-Qaeda affiliated groups.[266][267] The capture of Nazih Abdul-Hamed al-Ruqai, a senior Al-Qaeda operative wanted by the United States for his involvement in the 1998 United States embassy bombings, on October 5, 2013 by US Navy Seals, FBI and CIA agents illustrates the importance the US and other Western allies have placed on North Africa.[268]

Europe

Prior to the September 11 attacks, Al-Qaeda was present in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and its members were mostly former veterans of the El Mudžahid detachment of the Bosnian Muslim Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Three members of al Qaeda carried out the Mostar car bombing in 1997. They were closely linked to and financed by the Saudi High Commission for Relief of Bosnia and Herzegovina founed by then-prince King Salman of Saudi Arabia.

Before the 9/11 attacks and the US invasion of Afghanistan, recruits at Al-Qaeda training camps who had Western backgrounds were especially sought after by Al-Qaeda's military wing for conducting operations overseas. Language skills and knowledge of Western culture were generally found among recruits from Europe, such was the case with Mohamed Atta, an Egyptian national studying in Germany at the time of his training, and other members of the Hamburg Cell. Osama bin Laden and Mohammed Atef would later designate Atta as the ringleader of the 9/11 hijackers. Following the attacks, Western intelligence agencies determined that Al-Qaeda cells operating in Europe had aided the hijackers with financing and communications with the central leadership based in Afghanistan.[269][270]

In 2003, Islamists carried out a series of bombings in Istanbul killing fifty-seven people and injuring seven hundred. Seventy-four people were charged by the Turkish authorities. Some had previously met bin Laden, and though they specifically declined to pledge allegiance to al-Qaeda they asked for its blessing and help.[271][272]

In 2009, three Londoners, Tanvir Hussain, Assad Sarwar and Ahmed Abdullah Ali, were convicted of conspiring to detonate bombs disguised as soft drinks on seven airplanes bound for Canada and the U.S. The massively complex police and MI5 investigation of the plot involved more than a year of surveillance work conducted by over two hundred officers.[273][274] British and U.S. officials said the plot—unlike many similar homegrown European Islamic militant plots—was directly linked to al-Qaeda and guided by senior al-Qaeda members in Pakistan.[275][276]

In 2012, Russian Intelligence indicated that al-Qaeda had given a call for "forest jihad" and has been starting massive forest fires as part of a strategy of "thousand cuts".[277]

Arab world

Following Yemeni unification in 1990, Wahhabi networks began moving missionaries into the country in an effort to subvert the capitalist north. Although it is unlikely bin Laden or Saudi al-Qaeda were directly involved, the personal connections they made would be established over the next decade and used in the USS Cole bombing.[278] Concerns grow over Al Qaeda's group in Yemen.[279]

In Iraq, al-Qaeda forces loosely associated with the leadership were embedded in the Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad group commanded by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Specializing in suicide operations, they have been a "key driver" of the Sunni insurgency.[280] Although they played a small part in the overall insurgency, between 30% and 42% of all suicide bombings which took place in the early years were claimed by Zarqawi's group.[281] Reports have indicated that oversights such as the failure to control access to the Qa'qaa munitions factory in Yusufiyah have allowed large quantities of munitions to fall into the hands of al-Qaida.[282] In November 2010, the Islamic State of Iraq militant group, which is linked to al-Qaeda in Iraq, threatened to "exterminate Iraqi Christians".[283][284]

Significantly, it was not until the late 1990s that al-Qaeda began training Palestinians. This is not to suggest that resistance fighters are underrepresented in the network as a number of Palestinians, mostly coming from Jordan, wanted to join and have risen to serve high-profile roles in Afghanistan.[285] Rather, large groups such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad—which cooperate with al-Qaeda in many respects—have had difficulties accepting a strategic alliance, fearing that al-Qaeda will co-opt their smaller cells. This may have changed recently, as Israeli security and intelligence services believe al-Qaeda has managed to infiltrate operatives from the Occupied Territories into Israel, and is waiting for the right time to mount an attack.[285]

As of 2015[update], Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey are openly supporting the Army of Conquest,[204][286] an umbrella rebel group fighting in the Syrian Civil War against the Syrian government that reportedly includes an al-Qaeda linked al-Nusra Front and another Salafi coalition known as Ahrar ash-Sham.[208]

Kashmir

Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri consider India to be a part of the 'Crusader-Zionist-Hindu' conspiracy against the Islamic world.[287] According to the 2005 report 'Al Qaeda: Profile and Threat Assessment' by Congressional Research Service, bin Laden was involved in training militants for Jihad in Kashmir while living in Sudan in the early nineties. By 2001, Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen had become a part of the al-Qaeda coalition.[288] According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees al-Qaeda was thought to have established bases in Pakistan-administered Kashmir (in Azad Kashmir, and to some extent in Gilgit–Baltistan) during the 1999 Kargil War and continued to operate there with tacit approval of Pakistan's Intelligence services.[289]

Many of the militants active in Kashmir were trained in the same Madrasahs as Taliban and al-Qaeda. Fazlur Rehman Khalil of Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen was a signatory of al-Qaeda's 1998 declaration of Jihad against America and its allies.[290] In a 'Letter to American People' written by bin Laden in 2002 he stated that one of the reasons he was fighting America is because of its support to India on the Kashmir issue.[291][292] In November 2001, Kathmandu airport went on high alert after threats that bin Laden planned to hijack a plane from there and crash it into a target in New Delhi.[293] In 2002, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, on a trip to Delhi, suggested that al-Qaeda was active in Kashmir though he did not have any hard evidence.[294][295] He proposed hi tech ground sensors along the line of control to prevent militants from infiltrating into Indian administered Kashmir.[295] An investigation in 2002 unearthed evidence that al-Qaeda and its affiliates were prospering in Pakistan-administered Kashmir with tacit approval of Pakistan's National Intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence[296] In 2002, a special team of Special Air Service and Delta Force was sent into Indian Administered Kashmir to hunt for bin Laden after reports that he was being sheltered by Kashmiri militant group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen which had previously been responsible for 1995 Kidnapping of western tourists in Kashmir.[297] Britain's highest ranking al-Qaeda operative Rangzieb Ahmed had previously fought in Kashmir with the group Harkat-ul-Mujahideen and spent time in Indian prison after being captured in Kashmir.[298]

US officials believe that al-Qaeda was helping organize a campaign of terror in Kashmir in order to provoke conflict between India and Pakistan.[299] Their strategy was to force Pakistan to move its troops to the border with India, thereby relieving pressure on al-Qaeda elements hiding in northwestern Pakistan.[300] In 2006 al-Qaeda claimed they had established a wing in Kashmir; this has worried the Indian government.[290][301] However the Indian Army Lt. Gen. H.S. Panag, GOC-in-C Northern Command, said to reporters that the army has ruled out the presence of al-Qaeda in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir; furthermore he said that there is nothing that can verify reports from the media of al-Qaeda presence in the state. He however stated that al-Qaeda had strong ties with Kashmiri militant groups Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed based in Pakistan.[302] It has been noted that Waziristan has now become the new battlefield for Kashmiri militants fighting NATO in support of al-Qaeda and Taliban.[303][304][305] Dhiren Barot, who wrote the Army of Madinah in Kashmir[306] and was an al-Qaeda operative convicted for involvement in the 2004 financial buildings plot, had received training in weapons and explosives at a militant training camp in Kashmir.[307]

Maulana Masood Azhar, the founder of another Kashmiri group Jaish-e-Mohammed, is believed to have met bin Laden several times and received funding from him.[290] In 2002, Jaish-e-Mohammed organized the kidnapping and murder of Daniel Pearl in an operation run in conjunction with al-Qaeda and funded by bin Laden.[308] According to American counter-terrorism expert Bruce Riedel, al-Qaeda and Taliban were closely involved in the 1999 hijacking of Indian Airlines Flight 814 to Kandahar which led to the release of Maulana Masood Azhar & Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh from an Indian prison in exchange for the passengers. This hijacking, Riedel stated, was rightly described by then Indian Foreign minister Jaswant Singh as a 'dress rehearsal' for September 11 attacks.[309] Bin Laden personally welcomed Azhar and threw a lavish party in his honor after his release, according to Abu Jandal, bodyguard of bin Laden.[310][311] Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, who had been in Indian prison for his role in 1994 kidnappings of Western tourists in India, went on to murder Daniel Pearl and was sentenced to death by Pakistan. Al-Qaeda operative Rashid Rauf, who was one of the accused in 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot, was related to Maulana Masood Azhar by marriage.[312]

Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Kashmiri militant group which is thought to be behind 2008 Mumbai attacks, is also known to have strong ties to senior al-Qaeda leaders living in Pakistan.[313] In Late 2002, top al-Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah was arrested while being sheltered by Lashkar-e-Taiba in a safe house in Faisalabad.[314] The FBI believes that al-Qaeda and Lashkar have been 'intertwined' for a long time while the CIA has said that al-Qaeda funds Lashkar-e-Taiba.[314] French investigating magistrate Jean-Louis Bruguière, who was the top French counter-terrorism official, told Reuters in 2009 that 'Lashkar-e-Taiba is no longer a Pakistani movement with only a Kashmir political or military agenda. Lashkar-e-Taiba is a member of al-Qaeda.'[315][316]

In a video released in 2008, senior al-Qaeda operative American-born Adam Yahiye Gadahn stated that "victory in Kashmir has been delayed for years; it is the liberation of the jihad there from this interference which, Allah willing, will be the first step towards victory over the Hindu occupiers of that Islam land."[317]