Ethanol

This article is about the chemical compound. For beverages containing ethanol, see alcoholic beverage. For the use of ethanol as a fuel, see ethanol fuel. For its physiological effects, see effects of alcohol on the body.

| Ethanol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ethanol

| |||||

| General | |||||

| Systematic name | Ethanol | ||||

| Other names | Ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, hydroxyethane, EtOH | ||||

| Molecular formula | C2H6O | ||||

| SMILES | CCO | ||||

| Molar mass | 46.06844(232) g/mol | ||||

| Appearance | clear liquid | ||||

| CAS number | [64-17-5] | ||||

| Properties | |||||

| Density and phase | 0.789 g/cm3, liquid | ||||

| Solubility in water | Fully miscible | ||||

| Melting point | −114.3 °C (158.8 K) | ||||

| Boiling point | 78.4 °C (351.6 K) | ||||

| Acidity (pKa) | 15.9 (H+ from OH group) | ||||

| Viscosity | 1.200 cP at 20 °C | ||||

| Dipole moment | 1.69 D (gas) | ||||

| Hazards | |||||

| MSDS | External MSDS | ||||

| EU classification | Flammable (F) | ||||

| NFPA 704 |

| ||||

| R-phrases | Template:R11 | ||||

| S-phrases | Template:S2, Template:S7, Template:S16 | ||||

| Flash point | 13 °C (55.4 °F) | ||||

| RTECS number | KQ6300000 | ||||

| Supplementary data page | |||||

| Structure & properties | n, εr, etc. | ||||

| Thermodynamic data | Phase behaviour Solid, liquid, gas | ||||

| Spectral data | UV, IR, NMR, MS | ||||

| Related compounds | |||||

| Related alcohols | Methanol, 1-Propanol | ||||

| Other heteroatoms | Ethylamine, Ethyl chloride, Ethyl bromide, Ethanethiol | ||||

| Substituted ethanols | Ethylene glycol, Ethanolamine, 2-Chloroethanol | ||||

| Other compounds | Acetaldehyde, Acetic acid | ||||

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25°C, 100 kPa) Infobox disclaimer and references | |||||

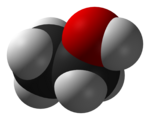

Ethanol, also known as ethyl alcohol or grain alcohol, is a flammable, tasteless, colorless, mildly toxic chemical compound with a distinctive odor, one of the alcohols that is most often found in alcoholic beverages. In common usage, it is often referred to simply as alcohol. Its molecular formula is C2H6O, variously represented as EtOH, C2H5OH or as its empirical formula C2H6O.

History

Ethanol has been used by humans since prehistory as the intoxicating ingredient in alcoholic beverages. Dried residues on 9000-year-old pottery found in northern China imply the use of alcoholic beverages even among Neolithic peoples.[1] Its isolation as a relatively pure compound was first achieved by Islamic alchemists who developed the art of distillation during the Abbasid caliphate, the most notable of whom was Al-Razi. The writings attributed to Jabir Ibn Hayyan (Geber) (721-815) mention the flammable vapors of boiled wine. Al-Kindī (801-873) unambiguously described the distillation of wine.[2] Distillation of ethanol from water yields a product that is at most 96% ethanol, because ethanol forms an azeotrope with water. Absolute ethanol was first obtained in 1796 by Johann Tobias Lowitz, by filtering distilled ethanol through charcoal.

Antoine Lavoisier described ethanol as a compound of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, and in 1808, Nicolas-Théodore de Saussure determined ethanol's chemical formula, Template:Inote and fifty years later, in 1858, Archibald Scott Couper published a structural formula for ethanol: this places ethanol among the first chemical compounds to have their chemical structures determined.[3]

Ethanol was first prepared synthetically in 1826, through the independent efforts of Henry Hennel in Great Britain and S.G. Sérullas in France. Michael Faraday prepared ethanol by the acid-catalysed hydration of ethylene in 1828, in a process similar to that used for industrial ethanol synthesis today.[4]

Physical properties

Ethanol's hydroxyl group is able to participate in hydrogen bonding. At the molecular level, liquid ethanol consists of hydrogen-bonded pairs of ethanol molecules; this phenomenon renders ethanol more viscous and less volatile than less polar organic compounds of similar molecular weight. In the vapor phase, there is little hydrogen bonding; ethanol vapor consists of individual ethanol molecules.

Ethanol has a refractive index of 1.3614.

Ethanol is a versatile solvent. It is miscible with water and with most organic liquids, including nonpolar liquids such as aliphatic hydrocarbons. Organic solids of low molecular weight are usually soluble in ethanol. Among ionic compounds, many monovalent salts are at least somewhat soluble in ethanol, with salts of large, polarizable ions being more soluble than salts of smaller ions. Most salts of polyvalent ions are practically insoluble in ethanol.

Several unusual phenomena are associated with mixtures of ethanol and water. Ethanol-water mixtures have less volume than their individual components: a mixture of equal volumes ethanol and water has only 96% of the volume of equal parts ethanol and water, unmixed. The addition of even a few percent of ethanol to water sharply reduces the surface tension of water. This property partially explains the tears of wine phenomenon: when wine is swirled inside a glass, ethanol evaporates quickly from the thin film of wine on the wall of the glass. As its ethanol content decreases, its surface tension increases, and the thin film beads up and runs down the glass in channels rather than as a smooth sheet.

Chemistry

The chemistry of ethanol is largely that of its hydroxyl group.

- Acid-base chemistry

Ethanol's hydroxyl proton is very weakly acidic; it is an even weaker acid than water. Ethanol can be quantitatively converted to its conjugate base, the ethoxide ion (CH3CH2O−), by reaction with an alkali metal such as sodium. This reaction evolves hydrogen gas:

- Nucleophilic substitution

In aprotic solvents, ethanol reacts with hydrogen halides to produce ethyl halides such as ethyl chloride and ethyl bromide via nucleophilic substitution:

Ethyl halides can also be produced by reacting ethanol by more specialized halogenating agents, such as thionyl chloride for preparing ethyl chloride, or phosphorus tribromide for preparing ethyl bromide.

- Esterification

Under acid-catalysed conditions, ethanol reacts with carboxylic acids to produce ethyl esters and water:

- RCOOH + HOCH2CH3 → RCOOCH2CH3 + H2O

The reverse reaction, hydrolysis of the resulting ester back to ethanol and the carboxylic acid, limits the extent of reaction, and high yields are unusual unless water can be removed from the reaction mixture as it is formed. Esterification can also be carried out using more a reactive derivative of the carboxylic acid, such as an acyl chloride or acid anhydride.

Ethanol can also form esters with inorganic acids. Diethyl sulfate and triethyl phosphate, prepared by reacting ethanol with sulfuric and phosphoric acid, respectively, are both useful ethylating agents in organic synthesis. Ethyl nitrite, prepared from the reaction of ethanol with sodium nitrite and sulfuric acid, was formerly a widely-used diuretic.

- Dehydration

Strong acids, such as sulfuric acid, can catalyse ethanol's dehydration to form either diethyl ether or ethylene:

- 2 CH3CH2OH → CH3CH2OCH2CH3 + H2O

Which product, diethyl ether or ethylene, predominates depends on the precise reaction conditions.

- Oxidation

Ethanol can be oxidized to acetaldehyde, and further oxidized to acetic acid. In the human body, these oxidation reactions are catalysed by enzymes. In the laboratory, aqueous solutions of strong oxidizing agents, such as chromic acid or potassium permanganate, oxidize ethanol to acetic acid, and it is difficult to stop the reaction at acetaldehyde at high yield. Ethanol can be oxidized to acetaldehyde, without overoxidation to acetic acid, by reacting it with pyridinium chromic chloride.

Production

Ethanol is produced both as a petrochemical, through the hydration of ethylene, and biologically, by fermenting sugars with yeast.

Ethylene hydration

Ethanol for use as industrial feedstock is most often made from petrochemical feedstocks, typically by the acid-catalyzed hydration of ethylene, represented by the chemical equation

The catalyst is most commonly phosphoric acid, adsorbed onto a porous support such as diatomaceous earth or charcoal; this catalyst was first used for large-scale ethanol production by the Shell Oil Company in 1947.[5] Solid catalysts, mostly various metal oxides, have also been mentioned in the chemical literature.

In an older process, first practiced on the industrial scale in 1930 by Union Carbide[6], but now almost entirely obsolete, ethene was hydrated indirectly by reacting it with concentrated sulfuric acid to product ethyl sulfate, which was then hydrolysed to yield ethanol and regenerate the sulfuric acid:

- C2H4 + H2SO4 → CH3CH2SO4H

- CH3CH2SO4H + H2O → CH3CH2OH + H2SO4

Fermentation

Ethanol for use in alcoholic beverages, and the vast majority of ethanol for use as fuel, is produced by fermentation: when certain species of yeast (most importantly, Saccharomyces cerevisiae) metabolize sugar in the absence of oxygen, they produce ethanol and carbon dioxide. The overall chemical reaction conducted by the yeast may be represented by the chemical equation

The process of culturing yeast under conditions to produce alcohol is referred to as brewing. Brewing can only produce relatively dilute concentrations of ethanol in water; concentrated ethanol solutions are toxic to yeast. The most ethanol-tolerant strains of yeast can survive in up to about 25% ethanol (by volume).

During the fermentation process, it is important to prevent oxygen getting to the ethanol, since otherwise the ethanol would be oxidised to acetic acid (vinegar). Also, in the presence of oxygen, the yeast would undergo aerobic respiration to produce just carbon dioxide and water, without producing ethanol.

In order to produce ethanol from starchy materials such as cereal grains, the starch must first be broken down into sugars. In brewing beer, this has traditionally been accomplished allowing the grain to germinate, or malt. In the process of germination, the seed produces enzymes that can break its starches into sugars. For fuel ethanol, this hydrolysis of starch into glucose is accomplished more rapidly by treatment with dilute sulfuric acid, fungal amylase enzymes, or some combination of the two.

At petroleum prices like those that prevailed through much of the 1990s, ethylene hydration was a decidedly more economical process than fermentation for producing purified ethanol. Recent increases in petroleum prices, coupled with perennial uncertainty in agricultural prices, make forecasting the relative production costs of fermented versus petrochemical ethanol difficult at the present time.

Purification

The product of either ethylene hydration or brewing is an ethanol-water mixture. For most industrial and fuel uses, the ethanol must be purified. Fractional distillation can concentrate ethanol to 96% volume; the mixture of 96% ethanol and 4% water is an azeotrope with a boiling point of 78.2 °C, and cannot be further purified by distillation. Therefore, 95% ethanol in water is a fairly common solvent.

After distillation ethanol can be further purified by "drying" it using lime or salt. Lime, (calcium oxide), when mixed with the water in ethanol will form calcium hydroxide, which then can be separated. Dry salt will dissolve some of the water content of the ethanol as it passes through, leaving a purer alcohol.[7]

Several approaches are used to produce absolute ethanol. The ethanol-water azeotrope can be broken by the addition of a small quantity of benzene. Benzene, ethanol, and water form a ternary azeotrope with a boiling point of 64.9 °C. Since this azeotrope is more volatile than the ethanol-water azeotrope, it can be fractionally distilled out of the ethanol-water mixture, extracting essentially all of the water in the process. The bottoms from such a distillation is anhydrous ethanol, with several parts per million residual benzene. Benzene is toxic to humans, and cyclohexane has largely supplanted benzene in its role as the entrainer in this process.

Alternatively, a molecular sieve can be used to selectively absorb the water from the 96% ethanol solution. Synthetic zeolite in pellet form can be used, as well as a variety of plant-derived absorbents, including cornmeal, straw, and sawdust. The zeolite bed can be regenerated essentially an unlimited number of times by drying it with a blast of hot carbon dioxide. Cornmeal and other plant-derived absorbents cannot readily be regenerated, but where ethanol is made from grain, they are often available at low cost. Absolute ethanol produced this way has no residual benzene, and can be used as fuel, or, when diluted, can even be used to fortify port and sherry in traditional winery operations.

At pressures less than atmospheric pressure, the composition of the ethanol-water azeotrope shifts to more ethanol-rich mixtures, and at pressures less than 70 torr (9.333 kPa) , there is no azeotrope, and it is possible to distill absolute ethanol from an ethanol-water mixture. While vacuum distillation of ethanol is not presently economical, pressure-swing distillation is a topic of current research. In this technique, a reduced-pressure distillation first yields an ethanol-water mixture of more than 96% ethanol. Then, fractional distillation of this mixture at atmospheric pressure distills off the 96% azeotrope, leaving anhydrous ethanol at the bottoms.

Prospective technologies

Glucose for fermentation into ethanol can also be obtained from cellulose. Until recently, however, the cost of the cellulase enzymes that could hydrolyse cellulose has been prohibitive. The Canadian firm Iogen brought the first cellulose-based ethanol plant on-stream in 2004.[8] The primary consumer thus far has been the Canadian government, which, along with the United States government (particularly the Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory), has invested millions of dollars into assisting the commercialization of cellulosic ethanol. Realization of this technology would turn a number of cellulose-containing agricultural byproducts, such as corncobs, straw, and sawdust, into renewable energy resources.

Cellulosic materials typically contain, in addition to cellulose, other polysaccharides, including hemicellulose. When hydrolysed, hemicellulose breaks down into mostly five-carbon sugars such as xylose. S. cerevisiae, the yeast most commonly used for ethanol production, cannot metabolize xylose. Other yeasts and bacteria are under investigation to metabolize xylose and so improve the ethanol yield from cellulosic material.[9][10]

The anaerobic bacterium Clostridium ljungdahlii, recently discovered in commercial chicken wastes, can produce ethanol from single-carbon sources including carbon monoxide and a mixture of hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Use of these bacteria to produce ethanol from synthesis gas has progressed to the pilot plant stage at the BRI Energy facility in Fayetteville, Arkansas.[11] Synthesis gas is a mixture of carbon monoxide and hydrogen that can be generated from the partial combustion of either fossil fuels or biomass; the heat released by gasification can be used to co-produce electricity with ethanol in the BRI process.

Denatured alcohol

In most jurisdictions, the sale of ethanol, as a pure substance or in the form of alcoholic beverages, is heavily taxed. In order to relieve non-beverage industries of this tax burden, governments specify formulations for denatured alcohol, which consists of ethanol blended with various additives to render it unfit for human consumption. These additives, called denaturants, are generally either toxic (such as methanol) or have unpleasant tastes or odors (such as denatonium benzoate).

Specialty denatured alcohols are denatured alcohol formulations intended for a particular industrial use, containing denaturants chosen so as not to interfere with that use. While they are not taxed, purchasers of specialty denatured alcohols must have a government-issued permit for the particular formulation they use and must comply with other regulations.

Completely denatured alcohols are formulations that can be purchased for any legal purpose, without permit, bond, or other regulatory compliance. It is intended that it be difficult to isolate a product fit for human consumption from completely denatured alcohol. For example, the completely denatured alcohol formulation used in the United Kingdom contains (by volume) 89.66% ethanol, 9.46% methanol, 0.50% pyridine, 0.38% naphtha, and is dyed purple with methyl violet.[12]

Feedstocks

Currently the main feedstock in the United States for the production of ethanol is corn, but trials of a new crop, switchgrass, are showing much greater yields.[citation needed]

The dominant ethanol feedstock in warmer regions is sugarcane.

In some parts of Europe, particularly France and Italy, wine is used as a feedstock due to massive oversupply.

Use

As a fuel

The largest single use of ethanol is as a motor fuel and fuel additive. The largest national fuel ethanol industries exist in Brazil. The Brazilian ethanol industry is based on sugarcane; as of 2004, Brazil produces 14 billion liters annually, enough to replace about 40% of its gasoline demand. Also as a result, they announced their independence from Middle East oil in April 2006. Most new cars sold in Brazil are flexible-fuel vehicles that can run on ethanol, gasoline, or any blend of the two. In addition, all fuel sold in Brazil contains at least 25% ethanol.

The products of the combustion of pure ethanol and pure oxygen (under ideal conditions) are water and carbon dioxide. The chemical combustion reaction of pure ethanol with pure oxygen is: C2H6O + 3 O2 → 2 CO2 + 3 H2O. However, the general reaction with stoichiometric air (normal atmospheric air) will produce a combination of water, carbon dioxide and an oxide of nitrogen. Nitrogen monoxide and nitrogen dioxide are possible products depending on combustion temperatures and reaction conditions.

The United States fuel ethanol industry is based largely on corn. As of 2005, its capacity is 15 billion liters annually. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 requires U.S. fuel ethanol production to increase to 28 billion liters (7.5 billion gallons) by 2012. In the United States, ethanol is most commonly blended with gasoline as a blend of up to 10% ethanol, known as E10 and nicknamed "gasohol". This blend is widely sold throughout the U.S. Midwest, which contains the nation's chief corn-growing centers.

In 2005, the Indy Racing League announced its cars will run on a 10% ethanol - 90% methanol blend fuel, and, in 2007, the cars will race on 100% ethanol.

Pakistan, India, China, Thailand and Japan have now launched their national gasohol policies. Thailand started blending 10% ethanol for its ULG95 in 1985; now there are more than 4000 stations serving E10. The blending of 10% ethanol into 95 RON gasoline will be mandated by the end of 2006 and into 91 RON gasoline by the end of 2010. It is expected that once the production of ethanol from cassava and sugar cane molasses can be ramped up, a higher blending ratio like E20 or E85 or even Flexible Fuel Vehicles will be introduced to Thailand. Similarly, Pakistan has started ethanol blending with motor gasoline as a part of an experimental project called The Pilot Project. The blended fuel is 10 percent ethanol and 90 percent gasoline. It is initially available in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad through state-run Pakistan State Oil petrol pumps but eventually will be made available to the rest of the country.

Ethanol with a water content of 2% or less can be used as the alcohol in the production of biodiesel, replacing methanol, which is quite dangerous to work with.

General Motors of Canada are preparing the launch of E85 flex-fuel vehicles, and will be sold at the same price as their gasoline-only versions. Most of these new vehicles are being produced in Oshawa, Ontario.

General Motors in the United States states they have over 2 million vehicles on the road in all 50 states that are capable of running under a 85% ethanol-15% gasoline blend known as E85. In 2006, GM will produce more than 400,000 flexible fuel vehicles annually -- vehicles that can also operate on gasoline or E85 ethanol without any modifications or special switches.

Unfortunately, ethanol cannot be transported by pipeline due to its chemical volatility. It currently is transported by railways and barges. mother fucker sucker, lol

Also some of the problems experienced with ethanol include:

- Ethanol has only 66% of the energy content of gasoline (in terms of lower heating value with units of "BTU/US gallons").[13] So to match the detonation characteristics of gasoline at high-power settings, ethanol-based fuels require fuel-flow volume increases of nearly 40%. The same car will get more miles per gallon of gasoline than miles per gallon of ethanol.

- Ethanol-based fuels are not compatible with some fuel system components. Examples of extreme corrosion of ferrous components, the formation of salt deposits, jelly-like deposits on fuel strainer screens, and internal separation of portions of rubber fuel tanks have been observed in some vehicles using ethanol fuels.

- The use of ethanol-based fuels can negatively affect electric fuel pumps by increasing internal wear and undesirable spark generation.

- E-85 is not compatible with capacitance fuel level gauging indicators and may cause erroneous fuel quantity indications in vehicles that employ that system.

- E-85 is capable of dissolving large amounts of water at conditions down to -77°, thereby impeding the detection and removal of water from the fuel system.[citation needed]

- E-85 experiences heavy evaporation losses. [citation needed]

Some believe butanol fuel is a better option since it can be made from the same corn and other natural products, but the fermentation process is more effective as butanol bacteria can utilise a greater variety of sugars than ethanol yeast. It works in all existing cars not just flex fuel ones. It gets better gas-mileage than ethanol and gives lower emissions than petrol.[citation needed]

Alcoholic beverages

Alcoholic beverages vary considerably in their ethanol content and in the foodstuffs from which they are produced. Most alcoholic beverages can be broadly classified as fermented beverages, beverages made by the action of yeast on sugary foodstuffs, or as distilled beverages, beverages whose preparation involves concentrating the ethanol in fermented beverages by distillation. The ethanol content of a beverage is usually measured in terms of the volume fraction of ethanol in the beverage, expressed either as a percentage or in alcoholic proof units.

Fermented beverages can be broadly classified by the foodstuff from which they are fermented. Beers are made from cereal grains or other starchy materials, wines and ciders from fruit juices, and meads from honey. Cultures around the world have made fermented beverages from numerous other foodstuffs, and local and national names for various fermented beverages abound. Fermented beverages may contain up to 15–20% ethanol by volume, the upper limit being set by the yeast's tolerance for ethanol, or by the amount of sugar in the starting material.

Distilled beverages are made by distilling fermented beverages. Broad categories of distilled beverages include whiskies, distilled from fermented cereal grains; brandies, distilled from fermented fruit juices, and rum, distilled from fermented molasses or sugarcane juice. Vodka and similar neutral grain spirits can be distilled from any fermented material (grain or potatoes is most common); these spirits are so thoroughly distilled that no tastes from the particular starting material remain. Numerous other spirits and liqueurs are prepared by infusing flavors from fruits, herbs, and spices into distilled spirits. A traditional example is gin, the infusion of juniper berries into neutral grain alcohol.

In a few beverages, ethanol is concentrated by means other than distillation. Applejack is traditionally made by freeze distillation: water is frozen out of fermented apple cider, leaving a more ethanol-rich liquid behind. Fortified wines are prepared by adding brandy or some other distilled spirit to partially-fermented wine. This kills the yeast and conserves some of the sugar in grape juice; such beverages are not only more ethanol-rich, but also sweeter than other wines.

Chemicals derived from ethanol

- Ethyl esters

In the presence of an acid catalyst (typically sulfuric acid) ethanol reacts with carboxylic acids to produce ethyl esters:

The two largest-volume ethyl esters are ethyl acrylate (from ethanol and acrylic acid) and ethyl acetate (from ethanol and acetic acid). Ethyl acrylate is a monomer used to prepare acrylate polymers for use in coatings and adhesives. Ethyl acetate is a common solvent used in paints, coatings, and in the pharmaceutical industry; its most familiar application in the household is as a solvent for nail polish. A variety of other ethyl esters are used in much smaller volumes as artificial fruit flavorings.

- Vinegar

Vinegar is a dilute solution of acetic acid prepared by the action of Acetobacter bacteria on ethanol solutions. Although traditionally prepared from alcoholic beverages including wine, apple cider, and unhopped beer, vinegar can also be made from solutions of industrial ethanol. Vinegar made from distilled ethanol is called "distilled vinegar", and is commonly used in food pickling and as a condiment.

- Ethylamines

When heated to 150–220 °C over a silica- or alumina-supported nickel catalyst, ethanol and ammonia react to produce ethylamine. Further reaction leads to diethylamine and triethylamine:

- CH3CH2OH + NH3 → CH3CH2NH2 + H2O

- CH3CH2OH + CH3CH2NH2 → (CH3CH2)2NH + H2O

- CH3CH2OH + (CH3CH2)2NH → (CH3CH2)3N + H2O

The ethylamines find use in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals, agricultural chemicals, and surfactants.

- Other chemicals

Ethanol is a versatile chemical feedstock, and in the past has been used commercially to synthesize dozens of other high-volume chemical commodities. At the present, it has been supplanted in many applications by less costly petrochemical feedstocks. However, in markets with abundant agricultural products, but a less developed petrochemical infrastructure, such as China, India, and Brazil, ethanol can be used to produce chemicals that would be produced from petroleum in the West, including ethylene and butadiene.

Other uses

Ethanol is easily soluble in water in all proportions with a slight overall decrease in volume when the two are mixed. Absolute ethanol and 95% ethanol are themselves good solvents, somewhat less polar than water and used in perfumes, paints and tinctures. Other proportions of ethanol with water or other solvents can also be used as a solvent. Alcoholic drinks have a large variety of tastes because various flavor compounds are dissolved during brewing. When ethanol is produced as a mixing beverage it is a neutral grain spirit.

Ethanol is used in medical wipes and in most common antibacterial hand sanitizer gels at a concentration of about 62% (percentage by weight, not volume) as an antiseptic. The peak of the disinfecting power occurs around 70% ethanol; stronger and weaker solutions of ethanol have a lessened ability to disinfect. Solutions of this strength are often used in laboratories for disinfecting work surfaces. Ethanol kills organisms by denaturing their proteins and dissolving their lipids and is effective against most bacteria and fungi, and many viruses, but is ineffective against bacterial spores. Alcohol does not act like an antibiotic and is not effective against infections by ingestion. Ethanol in the low concentrations typically found in most alcoholic beverages does not have useful disinfectant or antiseptic properties, internally or externally.

Wine with less than 16% ethanol cannot protect itself against bacteria. Because of this, port is often fortified with ethanol to at least 18% ethanol by volume to halt fermentation for retaining sweetness and in preparation for aging, at which point it becomes possible to prevent the invasion of bacteria into the port, and to store the port for long periods of time in wooden containers that can 'breathe', thereby permitting the port to age safely without spoiling. Because of ethanol's disinfectant property, alcoholic beverages of 18% ethanol or more by volume can be safely stored for a very long time.

Metabolism and toxicology

Pure ethanol is a tasteless liquid with a strong and distinctive odor that produces a characteristic heat-like sensation when brought into contact with the tongue or mucous membranes. When applied to open wounds (as for disinfection) it produces a strong stinging sensation. Pure or highly concentrated ethanol may permanently damage living tissue on contact. Ethanol applied to unbroken skin cools the skin rapidly through evaporation.

In the human body, ethanol is first oxidized to acetaldehyde, and then to acetic acid. The first step is catalysed by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, and the second by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Some individuals have less effective forms of one or both of these enzymes, and can experience more severe symptoms from ethanol consumption than others. Conversely, those who have acquired ethanol tolerance have a greater quantity of these enzymes, and metabolize ethanol more rapidly.

| BAC (mg/dL) | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| 50 | Euphoria, talkativeness, relaxation |

| 100 | Central nervous system depression, impaired motor and sensory function, impaired cognition |

| >140 | Decreased blood flow to brain |

| 300 | Stupefaction, possible unconsciousness |

| 400 | Possible death |

| >550 | Death highly likely |

[14] The amount of ethanol in the body is typically quanitified by blood alcohol content (BAC), the milligrams of ethanol per 100 milliliters of blood. The table at right summarizes the symptoms of ethanol consumption. Small doses of ethanol generally produce euphoria and relaxation; people experiencing these symptoms tend to become talkative and less inhibited, and may exhibit poor judgment. At higher dosages (BAC > 0.10), ethanol acts as a central nervous system depressant, producing at progressively higher dosages, impaired sensory and motor function, slowed cognition, stupefaction, unconsciousness, and possible death.

The initial product of ethanol metabolism, acetaldehyde, is more toxic than ethanol itself. The body can quickly detoxify some acetaldehyde by reaction with glutathione and similar thiol-containing biomolecules. When acetaldehyde is produced beyond the capacity of the body's glutathione supply to detoxify it, it accumulates in the bloodstream until further oxidized to acetic acid. The headache, nausea, and malaise associated with an alcohol hangover stem from a combination of dehydration and acetaldehyde poisoning; many health conditions associated with chronic ethanol abuse, including liver cirrhosis, alcoholism, and some forms of cancer, have been linked to acetaldehyde.[citation needed] Some medications, including paracetamol (acetaminophen), as well as exposure to organochlorides, can deplete the body's glutathione supply, enhancing both the acute and long-term risks of even moderate ethanol consumption. Frequent use of alcoholic beverages has also been shown to be a major contributing factor in cases of elevated blood levels of triglycerides. [1]

Ethanol has been shown to increase the growth of Acinetobacter baumannii, a bacterium responsible for pneumonia, meningitis and urinary tract infections. This finding may contradict the common misconception that drinking alcohol could kill off a budding infection. (Smith and Snyder, 2005)

Hazards

- Ethanol-water solutions greater than about 50% ethanol by volume are flammable and easily ignited.

See also

- Breathalyzer

- Corn liquor

- Ethanol (data page)

- Alcohol fuel

- Alcoholic beverage

- Effects of alcohol on the body

- Biodiesel

- Denatured alcohol

- Isopropyl alcohol

- List of energy topics

- 2,2,2-Trichloroethanol

- 1-Propanol

- Rubbing alcohol

- Timeline of alcohol fuel

References

- ^ Roach, J. (July 18 2005) "9,000-Year-Old Beer Re-Created From Chinese Recipe." National Geographic News. Accessed 14 November 2005.

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan "Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources." Accessed 14 November 2005.

- ^ Couper, A.S. (1858). "On a new chemical theory." Philosophical magazine 16, 104–116. Online reprint

- ^ Hennell, H. (1828). "On the mutual action of sulfuric acid and alcohol, and on the nature of the process by which ether is formed." Philosophical Transactions 118, 365–371.

- ^ Lodgsdon, J.E. (1994). "Ethanol." In J.I. Kroschwitz (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 4th ed. vol. 9, p. 820. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Lodgsdon, J.E. (1994). p. 817

- ^ Mathewson, S.W. (1980). "Drying the Alcohol". The Manual for the Home and Farm Production of Alcohol Fuel. Ten Speed Press. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Ritter, S.K. (May 31 2004). "Biomass or Bust." Chemical & Engineering News 82(22), 31–34.

- ^ http://www.lub.lu.se/cgi-bin/show_diss.pl?db=global&fname=tec_748.html

- ^ http://www.metabolicengineering.gov/me2001/2001Kompala.pdf

- ^ http://www.brienergy.com/

- ^ Great Britain (2005). The Denatured Alcohol Regulations 2005. Statutory Instrument 2005 No. 1524.

- ^ http://www.eere.energy.gov/afdc/pdfs/fueltable.pdf

- ^ Pohorecky, L.A., and J. Brick. (1988). "Pharmacology of ethanol." Pharmacology & Therapeutics 36(3), 335-427.

- "Alcohol." (1911). In Hugh Chisholm (Ed.) Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. Online reprint

- Lodgsdon, J.E. (1994). "Ethanol." In J.I. Kroschwitz (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, 4th ed. vol. 9, pp. 812–860. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Smith, M.G., and M. Snyder. (2005). "Ethanol-induced virulence of Acinetobacter baumannii". American Society for Microbiology meeting. June 5-June 9. Atlanta.

- Sci-toys website explanation of US denatured alcohol designations

- Boyce, John M., and Pittet Didier. (2003). “Hand Hygiene in Healthcare Settings.” Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia, United States.

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 0044

- National Pollutant Inventory - Ethanol Fact Sheet

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Coordinates of the ethanol molecule on Computational Chemistry Wiki. Accessed on 8 September 2005.

- Molview from bluerhinos.co.uk See Ethanol in 3D

- NIST Chemistry WebBook page for ethanol