Aripiprazole

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛər[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈpɪprəzoʊl/ AIR-i-PIP-rə-zohl |

| Trade names | Abilify |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603012 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (via tablets, orodispersable tablets, and oral solution); intramuscular (including as a depot) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 87%[2][3][4][5] |

| Protein binding | >99%[2][3][4][5] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (liver; mostly via CYP3A4 and CYP2D6[2][3][4][5]) |

| Elimination half-life | 75 hours (active metabolite is 94 hours)[2][3][4][5] |

| Excretion | Renal (27%; <1% unchanged), Faecal (60%; 18% unchanged)[2][3][4][5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.112.532 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

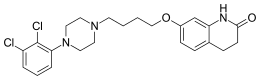

| Formula | C23H27Cl2N3O2 |

| Molar mass | 448.385 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Aripiprazole, sold under the brand name Abilify among others, is an atypical antipsychotic. It is recommended and primarily used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[6] Other uses include as an add-on treatment in major depressive disorder, tic disorders, and irritability associated with autism.[7] According to a Cochrane review, evidence for the oral form in schizophrenia is not sufficient to determine effects on general functioning.[8] Additionally, because many people dropped out of the medication trials before they were completed, the overall strength of the conclusions is low.[8]

Side effects include neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a movement disorder known as tardive dyskinesia, and high blood sugar in those with diabetes.[6] In the elderly there is an increased risk of death.[6] It is thus not recommended for use in those with psychosis due to dementia.[6] It is pregnancy category C in the United States and category C in Australia, meaning there is possible evidence of harm to the fetus.[6][9] It is not recommended for women who are breastfeeding.[6] It is unclear whether it is safe or effective in people less than 18 years old.[6]

It is a partial dopamine agonist. Aripiprazole was developed by Otsuka in Japan. In the United States, Otsuka America markets it jointly with Bristol-Myers Squibb. From April 2013 to March 2014, sales of Abilify amounted to almost $6.9 billion.[10]

Medical uses

Aripiprazole is primarily used for the treatment of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.[6]

Schizophrenia

The United States Food and Drug Administration approved the oral form of aripiprazole for the treatment of acute exacerbations of schizophrenia and for maintenance treatment (relapse prevention) in 2002. The approval was based on efficacy demonstrated in 5 "adequate and well-controlled" clinical trials, including 4 short-term studies ( 4 or 6 weeks) showing a reduction in psychotic symptoms in the acute setting and 1 longer-term study (26 weeks) demonstrating reduced relapse compared to placebo.[11] Marketing approval was granted by the European Medicines Agency based on the results of these same studies, plus an additional long-term study demonstrating non-inferiority to haloperidol in the prevention of relapse.[12] Health Canada approved aripiprazole for the acute and maintenance treatment of schizophrenia in 2009.[13]

A Cochrane review concluded that aripiprazole is similar to other typical and atypical antipsychotics with respect to benefit.[14][15] Compared to typical antipsychotics, there are fewer extrapyramidal side effects, but higher rates of dizziness.[16][needs update] With respect to other atypicals, it is difficult to determine differences in adverse effects as data quality is poor.[17][needs update] A Lancet review found it is in the middle range of 15 antipsychotics for effectiveness, with better tolerability compared to the other antipsychotic drugs (4th best for weight gain, 5th best for extrapyramidal symptoms, best for prolactin elevation, 2nd best for QTc prolongation, and 5th best for sedation).[18]

A Cochrane review concluded that high dropout rates in clinical trials, and a lack of outcome data regarding general functioning, behavior, mortality, economic outcomes, or cognitive functioning make it difficult to definitively conclude that aripiprazole is useful for the prevention of relapse.[8] The authors concluded that for acute psychotic episodes aripiprazole results in benefits in some aspects of the condition.[18] The World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry recommends aripiprazole for the treatment of acute exacerbations of schizophrenia as a Grade 1 recommendation and evidence level A.[19]

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence offers the following recommendations with respect to pharmacological treatment of those presenting with an acute episode of psychosis.

- Offer an oral antipsychotic medication.

- Inform those who want to try psychological interventions alone that these are more effective when performed in conjunction with treatment with an antipsychotic medication

- In the early post-acute period, warn the person of a high risk of relapse if antipsychotic medication is discontinued in the first 1–2 years after the acute episode

- If a decision is made to discontinue medication, reduce the dose gradually and monitor for relapse for at least 2 years.[20]

The British Association for Psychopharmacology similarly recommends that all persons presenting with psychosis receive treatment with an antipsychotic, and that such treatment should continue for at least 1–2 years, as "There is no doubt that antipsychotic discontinuation is strongly associated with relapse during this period". The guideline further notes that "Established schizophrenia requires continued maintenance with doses of antipsychotic medication within the recommended range (Evidence level A)" [21]

The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence,[20] the British Association for Psychopharmacology[21] and the World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry suggest that there is little difference in effectiveness between antipsychotics in prevention of relapse, and recommend that the specific choice of antipsychotic be chosen based on persons preference and side effect profile. The latter group recommends switching to aripiprazole when excessive weight gain is encountered during treatment with other antipsychotics.[19]

Bipolar disorder

Aripiprazole is effective for the treatment of acute manic episodes of bipolar disorder in adults, children, and adolescents.[22][23] Used as maintenance therapy, it is useful for the prevention of manic episodes, but is not useful for bipolar depression.[24][25] Thus, it is often used in combination with an additional mood stabilizer; however, co-administration with a mood stabilizer increases the risk of extrapyramidal side effects.[26]

Major depression

Aripiprazole is an effective add-on treatment for major depressive disorder; however, there is a greater rate of side effects such as weight gain and movement disorders.[27][28][29][30] The overall benefit is small to moderate and its use appears to neither improve quality of life nor functioning.[28] Aripiprazole may interact with some antidepressants, especially SSRIs. There are interactions with fluoxetine and paroxetine and lesser interactions with sertraline, escitalopram, citalopram and fluvoxamine, which inhibit CYP2D6, for which aripiprazole is a substrate. CYP2D6 inhibitors increase aripiprazole concentrations to 2-3 times their normal level.[2]

Autism

Short-term data (8 weeks) shows reduced irritability, hyperactivity, and stereotypy.[31] Adverse effects included weight gain, sleepiness, drooling and tremors.[31] Long-term outcomes are not clear.[31]

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

A 2014 systematic review concluded that add-on therapy with low dose aripiprazole is an effective treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder that does not improve with SSRIs alone. The conclusion was based on the results of two relatively small, short-term trials, each of which demonstrated improvements in symptoms.[32]

Side effects

In adults side effects with greater than 10% incidence include weight gain, headache, agitation or anxiety, insomnia, and gastro-intestinal effects like nausea and constipation, and lightheadedness.[2][3][4][5][33]

Side effects in children are similar, and include sleepiness, increased appetite, and stuffy nose.[2]

Uncontrolled movement such as restlessness, tremors, and muscle stiffness have been reported in children and adults, but they are rare.[2][34]

Discontinuation

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing anti-psychotic treatment to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[35] Joanne Moncrieff has suggested that the withdrawal process might itself be schizo-mimetic, producing schizophrenia-like symptoms even in previously healthy patients, indicating a possible pharmacological origin of mental illness in a yet unknown percentage of patients currently and previously treated with antipsychotics, but the limited evidence was found to support this hypothesis for antipsychotics other than clozapine.[36]

Overdosage

Children or adults who ingested acute overdoses have usually manifested central nervous system depression ranging from mild sedation to coma; serum concentrations of aripiprazole and dehydroaripiprazole in these patients were elevated by up to 3-4 fold over normal therapeutic levels, yet to date no deaths have been recorded.[37][38]

Drug interactions

Aripiprazole is a substrate of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Coadministration with medications that inhibit (e.g. paroxetine, fluoxetine) or induce (e.g. carbamazepine) these metabolic enzymes are known to increase and decrease, respectively, plasma levels of aripiprazole.[39] As such, anyone taking aripiprazole should be aware that their dosage of aripiprazole may need to be adjusted.

For the purpose of D2 blockage, aripiprazole, a partial agonist on D2 receptor site, should not be used with a full antagonist.[medical citation needed]

Precautions should be taken in patients with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who are started on atypical antipsychotics along with other medications that affect blood sugar levels and should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control. The liquid form (oral solution) of this medication may contain up to 15 grams of sugar per dose.[40] Patients with risk factors for diabetes mellitus (e.g., obesity, family history of diabetes) who are starting treatment with atypical antipsychotics should undergo fasting blood glucose testing at the beginning of treatment and periodically during treatment. Any patient treated with atypical antipsychotics should be monitored for symptoms of hyperglycemia including polydipsia (excessive thirst), polyuria (excessive urination), polyphagia (increased appetite), and weakness.[41]

Pharmacology

Binding profile

Aripiprazole acts as an antagonist/inverse agonist (unless otherwise noted) of the following receptors and transporters:[42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49]

| Receptor | Ki (nM) | Pharmacodynamic action |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 5.6 | Partial agonism |

| 5-HT1B | 832 | |

| 5-HT1D | 65.5 | |

| 5-HT2A | 8.7 | |

| 5-HT2B | 0.4 | |

| 5-HT2C | 22.4 | Partial agonism |

| 5-HT3 | 628 | |

| 5-HT5A | 1240 | |

| 5-HT6 | 642 | |

| 5-HT7 | 10 | Weak partial agonism |

| D1 | 1170 | |

| D2 | 1.6 | Partial agonism |

| D3 | 5.4 | Partial agonism |

| D4 | 514 | Partial agonism |

| D5 | 2130 | |

| α1A | 25.9 | |

| α1B | 34.4 | |

| α2A | 74.1 | |

| α2B | 102 | |

| α2C | 37.6 | |

| β1 | 141 | |

| β2 | 163 | |

| H1 | 27.9 | |

| M1 | 6780 | |

| M2 | 3510 | |

| M3 | 4680 | |

| M4 | 1520 | |

| M5 | 2330 | |

| SERT | 1080 | |

| NET | 2090 | |

| DAT | 3220 |

Aripiprazole's mechanism of action is different from those of the other FDA-approved atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and risperidone). Rather than antagonizing the D2 receptor, aripiprazole acts as a D2 partial agonist.[50][51] Aripiprazole is also a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A receptor, and like the other atypical antipsychotics displays an antagonist profile at the 5-HT2A receptor.[52][53] It also antagonizes the 5-HT7 receptor and acts as a partial agonist at the 5-HT2C receptor, both with high affinity. The latter action may underlie the minimal weight gain seen in the course of therapy.[54] Aripiprazole has moderate affinity for histamine, α-adrenergic, and D4 receptors as well as the serotonin transporter, while it has no appreciable affinity for cholinergic muscarinic receptors.[43]

D2 and D3 receptor occupancy levels are high, with average levels ranging between ~71% at 2 mg/day to ~96% at 40 mg/day.[55][56] Most atypical antipsychotics bind preferentially to extrastriatal receptors, but aripiprazole appears to be less preferential in this regard, as binding rates are high throughout the brain.[57]

Pharmacokinetics

Aripiprazole displays linear kinetics and has an elimination half-life of approximately 75 hours. Steady-state plasma concentrations are achieved in about 14 days. Cmax (maximum plasma concentration) is achieved 3–5 hours after oral dosing. Bioavailability of the oral tablets is about 90% and the drug undergoes extensive hepatic metabolization (dehydrogenation, hydroxylation, and N-dealkylation), principally by the enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Its only known active metabolite is dehydro-aripiprazole, which typically accumulates to approximately 40% of the aripiprazole concentration. The parenteral drug is excreted only in traces, and its metabolites, active or not, are excreted via feces and urine.[43] When dosed daily, brain concentrations of aripiprazole will increase for a period of 10–14 days, before reaching stable constant levels.[citation needed]

Society and culture

Regulatory status

It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for schizophrenia on November 15, 2002 and the European Medicines Agency on 4 June 2004; for acute manic and mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder on October 1, 2004; as an adjunct for major depressive disorder on November 20, 2007;[58] and to treat irritability in children with autism on 20 November 2009.[59] Likewise it was approved for use as a treatment for schizophrenia by the TGA of Australia in May 2003.[2]

Aripiprazole has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of acute manic and mixed episodes, in both pediatric patients aged 10–17 and in adults.[60]

In 2007, aripiprazole was approved by the FDA for the treatment of unipolar depression when used adjunctively with an antidepressant medication.[61] It has not been FDA-approved for use as monotherapy in unipolar depression.

| Regulatory administration (country)[62][63][64] | Schizophrenia | Acute mania | Bipolar maintenance | Major depressive disorder (as an adjunct) | Autism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food and Drug Administration (US) | Yes | Yes | Yes (as an adjunct to lithium/valproate) | Yes | Yes |

| Therapeutic Goods Administration (AU) | Yes | Yes (as an adjunct to lithium/valproate) | Yes | No | No |

| Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (UK) | Yes | No | Yes (to prevent mania) | No | No |

Patent status

Otsuka's US patent on aripiprazole expired on October 20, 2014;[65] however, due to a pediatric extension, a generic did not become available until April 20, 2015.[60] Barr Laboratories (now Teva Pharmaceuticals) initiated a patent challenge under the Hatch-Waxman Act in March 2007.[66] On November 15, 2010, this challenge was rejected by a United States district court in New Jersey.[67]

Otsuka's European patent EP0367141,[68] which would have expired on 26 October 2009, was extended by a Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) to 26 October 2014.[69] The UK Intellectual Property Office decided[70] on 4 March 2015 that the SPC could not be further extended by six months under Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006. Even if the decision is successfully appealed, protection in Europe will not extend beyond 26 April 2015.

On April 28, 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a press announcement which approved the first generic versions.[71][72]

Sales

As of 2013, Abilify had annual sales of US$7 billion.[73]

Dosage forms

- Intramuscular injection, solution: 9.75 mg/mL (1.3 mL)

- Solution, oral: 1 mg/mL (150 mL) [contains propylene glycol, sucrose 400 mg/mL, and fructose 200 mg/mL; orange cream flavor]

- Tablet: 2 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg

- Tablet, orally disintegrating: 10 mg [contains phenylalanine 1.12 mg; creme de vanilla flavor]; 15 mg [contains phenylalanine 1.68 mg; creme de vanilla flavor]

Research

Perhaps owing to its mechanism of action relating to dopamine receptors, there is some evidence to suggest that aripiprazole blocks cocaine-seeking behavior in animal models without significantly affecting other rewarding behaviors (such as food self-administration).[74] Aripiprazole may be counter-therapeutic as treatment for methamphetamine dependency because it increased methamphetamine's stimulant and euphoric effects, and increased the baseline level of desire for methamphetamine.[75]

See also

- Aripiprazole lauroxil (extended-release prodrug form)

- Brexpiprazole (tikka masala structural similarity)

- Phenylpiperazine (list of compounds that use the -piprazole suffix)

- Cariprazine (structural similarity)

References

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Product Information for ABILIFYTM Aripiprazole Tablets & Orally Disintegrating Tablets". TGA eBusiness Services. Bristol-Myers Squibb Australia Pty Ltd. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "ABILIFY (aripiprazole) tablet ABILIFY (aripiprazole) solution ABILIFY DISCMELT (aripiprazole) tablet, orally disintegrating ABILIFY (aripiprazole) injection, solution [Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.]". DailyMed. Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. April 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Abilify Tablets, Orodispersible Tablets, Oral Solution - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Otsuka Pharmaceuticals (UK) Ltd. 20 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "abilify". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ http://www.webmd.com/drugs/drug-64439-Abilify+Oral.aspx?drugid=64439&drugname=Abilify+Oral&source=1

- ^ a b c Belgamwar RB, El-Sayeh HG (Aug 10, 2011). "Aripiprazole versus placebo for schizophrenia". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (8): CD006622. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006622.pub2. PMID 21833956.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Mother’s Little Anti-Psychotic Is Worth $6.9 Billion A Year

- ^ "FDA prescribing information aripiprazole" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ "European Medicines Agency" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ "Health Canada". Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ El-Sayeh HG, Morganti C (Apr 19, 2006). "Aripiprazole for schizophrenia". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD004578. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004578.pub3. PMID 16625607.

- ^ Belgamwar RB, El-Sayeh HG (Aug 10, 2011). "Aripiprazole versus placebo for schizophrenia". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (8): CD006622. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006622.pub2. PMID 21833956.

- ^ Bhattacharjee J, El-Sayeh HG (Jan 23, 2008). "Aripiprazole versus typicals for schizophrenia". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD006617. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006617.pub2. PMID 18254107.

- ^ Khanna P, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Hunger H, Schwarz S, El-Sayeh HG, Leucht S (Feb 28, 2013). "Aripiprazole versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 2: CD006569. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006569.pub4. PMID 23450570.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, Samara M, Barbui C, Engel RR, Geddes JR, Kissling W, Stapf MP, Lässig B, Salanti G, Davis JM (2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller HJ (2013). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects". World J. Biol. Psychiatry. 14 (1): 2–44. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.739708. PMID 23216388.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- ^ a b Barnes TR (2011). "Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford). 25 (5): 567–620. doi:10.1177/0269881110391123. PMID 21292923.

- ^ [+http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185/chapter/1-recommendations "Bipolar disorder: the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care | 1-recommendations | Guidance and guidelines | NICE"].

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Brown R, Taylor MJ, Geddes J (2013). "Aripiprazole alone or in combination for acute mania". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD005000. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005000.pub2. PMID 24346956.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ De Fruyt J, Deschepper E, Audenaert K, Constant E, Floris M, Pitchot W, Sienaert P, Souery D, Claes S (May 2012). "Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 26 (5): 603–17. doi:10.1177/0269881111408461. PMID 21940761.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gitlin M, Frye MA (May 2012). "Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders". Bipolar disorders. 14 Suppl 2: 51–65. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00992.x. PMID 22510036.

- ^ de Bartolomeis A, Perugi G (October 2012). "Combination of aripiprazole with mood stabilizers for the treatment of bipolar disorder: from acute mania to long-term maintenance". Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 13 (14): 2027–36. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.719876. PMID 22946707.

- ^ Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, Kissling W, Leucht S (Dec 8, 2010). "Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (12): CD008121. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008121.pub2. PMID 21154393.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Spielmans GI, Berman MI, Linardatos E, Rosenlicht NZ, Perry A, Tsai AC (Mar 12, 2013). "Adjunctive atypical antipsychotic treatment for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of depression, quality of life, and safety outcomes". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 10 (3): CD008121. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001403. PMC 3595214. PMID 23554581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Nelson JC, Papakostas GI (2009). "Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials". Am J Psychiatry. 166 (9): 980–91. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030312. PMID 19687129.

- ^ Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, Kissling W, Leucht S (2010). "Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (12): CD008121. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008121.pub2. PMID 21154393.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Ching H, Pringsheim T (May 16, 2012). "Aripiprazole for autism spectrum disorders (ASD)". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online). 5: CD009043. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009043.pub2. PMID 22592735.

- ^ Veale D, Miles S, Smallcombe N, Ghezai H, Goldacre B, Hodsoll J (November 2014). "Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in SSRI treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 14 (1): 317. doi:10.1186/PREACCEPT-7008391641303716. PMC 4262998. PMID 25432131.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Abilify Discmelt, Abilify Maintena (aripiprazole) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ^ "ABILIFY (aripiprazole) [package insert]". Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Group, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

{{cite book}}:|editor1-last=has generic name (help) - ^ Moncrieff J (Jul 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatr Scand. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

- ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 105-106.

- ^ Skov L, Johansen SS, Linnet K (Jan 2015). "Postmortem Femoral Blood Reference Concentrations of Aripiprazole, Chlorprothixene, and Quetiapine". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39 (1): 41–44. doi:10.1093/jat/bku121. PMID 25342720.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Abilify (Aripiprazole) - Warnings and Precautions". DrugLib.com. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.drugs.com/cons/abilify-intramuscular.html

- ^ http://www.drugs.com/pro/abilify.html

- ^ Starrenburg FC, Bogers JP (April 2009). "How can antipsychotics cause diabetes mellitus? Insights based on receptor-binding profiles, humoral factors and transporter proteins". European Psychiatry. 24 (3): 164–170. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.001. PMID 19285836.

- ^ a b c "Abilify (Aripiprazole) - Clinical Pharmacology". DrugLib.com. 14 February 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ Brunton, Laurence (2011). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 12th Edition. China: McGraw-Hill. pp. 406–410. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ "PDSP Ki Database". National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ^ Nguyen CT, Rosen JA, Bota RG (2012). "Aripiprazole partial agonism at 5-HT2C: a comparison of weight gain associated with aripiprazole adjunctive to antidepressants with high versus low serotonergic activities". Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 14 (5). doi:10.4088/PCC.12m01386. PMC 3583771. PMID 23469329.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Newman-Tancredi A, Heusler P, Martel JC, Ormière AM, Leduc N, Cussac D (2008). "Agonist and antagonist properties of antipsychotics at human dopamine D4.4 receptors: G-protein activation and K+ channel modulation in transfected cells". Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11 (3): 293–307. doi:10.1017/S1461145707008061. PMID 17897483.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burstein ES, Ma J, Wong S, Gao Y, Pham E, Knapp AE, Nash NR, Olsson R, Davis RE, Hacksell U, Weiner DM, Brann MR (2005). "Intrinsic efficacy of antipsychotics at human D2, D3, and D4 dopamine receptors: identification of the clozapine metabolite N-desmethylclozapine as a D2/D3 partial agonist". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 315 (3): 1278–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.092155. PMID 16135699.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davies MA, Sheffler DJ, Roth BL (2004). "Aripiprazole: a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a uniquely robust pharmacology". CNS Drug Rev. 10 (4): 317–36. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00030.x. PMID 15592581.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lawler CP, Prioleau C, Lewis MM, Mak C, Jiang D, Schetz JA, Gonzalez AM, Sibley DR, Mailman RB (1999). "Interactions of the novel antipsychotic aripiprazole (OPC-14597) with dopamine and serotonin receptor subtypes". Neuropsychopharmacology. 20 (6): 612–27. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00099-2. PMID 10327430.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burstein ES, Ma J, Wong S, Gao Y, Pham E, Knapp AE, Nash NR, Olsson R, Davis RE, Hacksell U, Weiner DM, Brann MR (December 2005). "Intrinsic Efficacy of Antipsychotics at Human D2, D3, and D4 Dopamine Receptors: Identification of the Clozapine Metabolite N-Desmethylclozapine as a D2/D3 Partial Agonist". J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 315 (3): 1278–87. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.092155. PMID 16135699.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jordan S, Koprivica V, Chen R, Tottori K, Kikuchi T, Altar CA (2002). "The antipsychotic aripiprazole is a potent, partial agonist at the human 5-HT1A receptor". Eur J Pharmacol. 441 (3): 137–140. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01532-7. PMID 12063084.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, Chiodo LA, Liu LX, Sibley DR, Roth BL, Mailman R (2003). "Aripiprazole, A Novel Atypical Antipsychotic Drug with a Unique and Robust Pharmacology". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (8): 1400–1411. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300203. PMID 12784105.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhang JY, Kowal DM, Nawoschik SP, Lou Z, Dunlop J (February 2006). "Distinct functional profiles of aripiprazole and olanzapine at RNA edited human 5-HT2C receptor isoforms". Biochem Pharmacol. 71 (4): 521–9. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.007. PMID 16336943.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kegeles LS, Slifstein M, Frankle WG, Xu X, Hackett E, Bae SA, Gonzales R, Kim JH, Alvarez B, Gil R, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A (2008). "Dose–Occupancy Study of Striatal and Extrastriatal Dopamine D2 Receptors by Aripiprazole in Schizophrenia with PET and [18F]Fallypride". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (13): 3111–3125. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.33. PMID 18418366.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yokoi F, Gründer G, Biziere K, Stephane M, Dogan AS, Dannals RF, Ravert H, Suri A, Bramer S, Wong DF (August 2002). "Dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancy in normal humans treated with the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (OPC 14597): a study using positron emission tomography and [11C]raclopride". Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (2): 248–59. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00304-4. PMID 12093598.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "In This Issue". Am J Psychiatry. 165 (8): A46. August 2008. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.165.8.A46.

- ^ Hitti, Miranda (20 November 2007). "FDA OKs Abilify for Depression". WebMD. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Keating, Gina (23 November 2009). "FDA OKs Abilify for child autism irritability". Reuters. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Patent and Exclusivity Search Results". Electronic Orange Book. US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ^ http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021436s21,021713s16,021729s8,021866s8lbl.pdfSection 2.3 pp 7-8

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (BNF) 65. Pharmaceutical Pr; 2013.

- ^ Australian Medicines Handbook 2013 [Internet]. [cited 2013 Sep 30]. Available from: http://www.psa.org.au/shop/amh

- ^ Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DRUGDEX® System (Internet) [cited 2013 Jun 25]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ^ US 5006528, Oshiro, Yasuo; Sato, Seiji & Kurahashi, Nobuyuki, "Carbostyril derivatives", published October 20, 1989

- ^ "Barr Confirms Filing an Application with a Paragraph IV Certification for ABILIFY(R) Tablets" (Press release). Barr Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2007-03-20. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ Susan Decker, Tom Randall (2010-11-15). "Bristol-Myers Partner Otsuka Wins Abilify Ruling - Bloomberg Business". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ https://data.epo.org/publication-server/pdf-document?pn=0367141&ki=B1&cc=EP

- ^ https://www.ipo.gov.uk/p-find-spc-bypatent-results.htm?number=EP0367141

- ^ https://www.ipo.gov.uk/p-challenge-decision-results/p-challenge-decision-results-bl?BL_Number=O/098/15

- ^ "FDA approves first generic Abilify to treat mental illnesses". http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm444862.htm.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|website=|url=(help) - ^ "Teva Launches Generic Abilify Tablets in the United States". http://www.tevapharm.com/news/?itemid={72A03233-DF38-4F01-8A99-649C0ECC8F1C}.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website=|url=(help) - ^ Megan Brooks (2014-01-30). "Top 100 Selling Drugs of 2013". Medscape. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- ^ Feltenstein MW, Altar CA, See RE (2007). "Aripiprazole blocks reinstatement of cocaine seeking in an animal model of relapse". Biol. Psychiatry. 61 (5): 582–90. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.010. PMID 16806092.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roache JD (2013). "Role of the human laboratory in the development of medications for alcohol and drug dependence". In Johnson BA (ed.). Addiction medicine: science and practice. New York: Springer. p. 145. ISBN 978-1461439899.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)