Antikythera wreck

The Antikythera wreck is a Roman shipwreck dating from the 2nd quarter of the 1st century BC.[1][2] It was discovered by sponge divers off Point Glyphadia on the Greek island of Antikythera in 1900.

The wreck yielded numerous statues, coins and other artifacts dating back to the 4th century BC, as well as the severely corroded remnants of a device many regard as the world's oldest known analog computer, the Antikythera mechanism. 35°53′23″N 23°18′28″E / 35.8897°N 23.3078°E

Discovery

In October 1900, a team of sponge divers led by Captain Dimitrios Kondos decided to wait out a severe storm hampering their return from Africa at the Greek island of Antikythera. While there they began diving for sponges off the island's coastline wearing the standard diving dresses — canvas suits and copper helmets – of the time.

Elias Stadiatis was the first to lay eyes on a shipwreck 45 meters down, who quickly signaled to be pulled to the surface. He described the scene as a heap of rotting corpses and horses lying on the sea bed. Thinking the diver was drunk from the nitrogen in his breathing mix at that depth, Kondos himself dove, soon returning with the arm of a bronze statue. While waiting for the storm to abate the divers retrieved as many small artifacts from the wreck as they could.

Artifact recovery

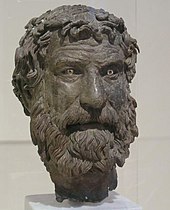

Together with the Greek Education Ministry and the Royal Hellenic Navy, the sponge divers salvaged numerous artifacts from the waters. By the middle of 1901, divers had recovered statues arbitrarily named "the philosopher", the Youth of Antikythera (Ephebe) of ca. 340 BC, a "Hercules", Ulysses, Diomedes and his horses, a Hermes, an Apollo, a marble statue of a bull and a bronze lyre, much marvelous glasswork. Many other small and common artifacts were also found, and were brought to the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

The death of one diver and the paralysis of some others due to decompression sickness put an end to work at the site during the summer of 1901. The French naval officer and explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau would later dive there, in the fall of 1976, to search and recover many more artifacts.[3]

On 17 May 1902, however, the former Minister of Education Spyridon Stais made the most celebrated find at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. When examining the artifacts that had been recovered, he noticed that a severely corroded piece of bronze had inscriptions and a gear wheel embedded in it. The object would come to be known as the Antikythera mechanism or astrolabe. Originally thought to be one of the first forms of a mechanised clock or an astrolabe, it is at times referred to as the world’s oldest known analog computer.[4]

Dating

Although the retrieval of artifacts from the shipwreck was highly successful and accomplished within two years, dating the site proved difficult and took much longer. Based on related works with known provenances, some of the bronze statues could be dated back to the 4th century BC, while the marble statues were found to be 1st century BC copies of earlier works.

Some scholars have speculated that the ship was carrying part of the loot of the Roman General Sulla from Athens in 86 BC, and might have been on its way to Italy. A reference by the Greek writer, Lucian, to one of Sulla's ships sinking in the Antikythera region gave rise to this theory. Supporting an early 1st-century BC date were domestic utensils and objects from the ship, similar to those known from other 1st-century BC contexts. The amphorae recovered from the wreck indicated a date of 80–70 BC, the Hellenistic pottery a date of 75–50 BC, and the Roman ceramics were similar to known mid-1st century types. The latest coin discovered in the 1970s during work by Jacques Cousteau and associates is datable between 76 and 67 BC.[2] It has been suggested that the sunken cargo ship was en route to Rome with looted treasures, to support a triumphal parade being planned for Julius Caesar.[5]

Remains of hull planks showed that the ship was made of elm, a wood often used by the Romans in their ships. Eventually in 1964 a sample of the hull planking was carbon dated, and delivered a calibrated calendar date of 220 BC ± 43 years. The disparity in the calibrated radiocarbon date and the expected date based on the ceramics and coins was explained by the sample plank originating from an old tree cut much earlier than the ship's sinking event.

Further evidence for an early 1st-century BC sinking date came in 1974, when Yale University Professor Derek de Solla Price published his interpretation of the Antikythera mechanism. He argued that the object was a calendar computer. From gear settings and inscriptions on the mechanism's faces, he concluded that the mechanism was made about 87 BC and lost only a few years later.

New expeditions

In 2012, marine archeologist Brendan P. Foley of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the United States received permission from the Greek Government to conduct new dives around the deep shoals of Antikythera. The divers began a preliminary three-week survey in October 2012 using SCUBA rebreather technology, to allow for extended dives down to a depth of 70 metres (230 ft), allowing a fuller, complete survey of the site.[6] New artifacts were recovered from the site in 2013 and 2014, including a large bronze spear believed to have been attached to a warrior statue.[7][8]

References

Citations

- ^ http://www.livescience.com/26009-antikythera-roman-shipwreck-two.html

- ^ a b "The Antikythera Shipwreck. The Ship, The Treasures, The Mechanism. National Archaeological Museum, April 2012 – April 2013". Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Tourism; National Archaeological Museum. Editors Nikolaos Kaltsas & Elena Vlachogianni & Polyxeni Bouyia. Athens: Kapon, 2012, ISBN 978-960-386-031-0.

- ^ "Jacques-Yves Cousteau".

- ^ Freeth, T.; Bitsakis, Y.; Moussas, X.; Seiradakis, J. H.; Tselikas, A.; Mangkou, E.; Zafeiropulou, M.; Hadland, R.; Bate, D.; Ramsey, A.; Allen, M.; Crawley, A.; Hockley, P.; Malzbender, T.; Gelb, D.; Ambrisco, W.; Edmunds, M. G. (2006). "Decoding the ancient Greek astronomical calculator known as the Antikythera Mechanism". Nature. 444 (7119): 587–591. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..587F. doi:10.1038/nature05357. PMID 17136087.

- ^

"Ancient 'Computer' Starts To Yield Secrets". Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Marchant, Jo. Return To Antikythera: Divers Revisit Wreck Where Ancient Computer Found, The Guardian, 2 October 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Antikythera shipwreck: treasures from the deep – in pictures". guardian.co.uk. 18 March 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Antikythera wreck yields new treasures". BBC. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

Bibliography

- P. Kabbadias, The Recent Finds off Cythera The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 21. (1901), pp. 205–208.

- Gladys Davidson Weinberg; Virginia R. Grace; G. Roger Edwards; Henry S. Robinson; Peter Throckmorton; Elizabeth K. Ralph, "The Antikythera Shipwreck Reconsidered", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Ser., Vol. 55, No. 3. (1965), pp. 3–48.

- Derek de Solla Price, "Gears from the Greeks. The Antikythera Mechanism: A Calendar Computer from ca. 80 B. C." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Ser., Vol. 64, No. 7. (1974), pp. 1–70.

- Nigel Pickford, The Atlas of Ship Wrecks & Treasures, p 13–15, ISBN 0-86438-615-X.

- Willard Bascom, Deep water, ancient ships: The treasure vault of the Mediterranean, ISBN 0-7153-7305-6.

Further reading

- Hilts, Philip J. (2015). "In Search of Sunken Treasure". Scientific American. 312 (1): 69–75. Bibcode:2014SciAm.312a..68H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0115-68.

External links

- A virtual tour of the exhibition dedicated to the Antikythera shipwreck at the National Archaeological Museum.

- The "Return to Antikythera" Dive Official Website

- Videos shown at the National Archaeological Museum "Antikythera Shipwreck" exhibition