Theodore Psalter

The Theodore Psalter is an illustrated manuscript and compilation of the Psalms and the Odes from the Old Testament.[1] "This Psalter has been held in the British Library since 1853 as Additional 19.352," wrote Princeton Art History professor Charles Barber in his first essay that is a companion to the Theodore Psalter E-Facsimile.[2] Barber called the Psalter, "One of the richest illuminated manuscripts to survive from Byzantium."[2]

Barber also wrote in his essay, "...the 208 folios of this manuscript include 440 separate images, making this the most fully illuminated Psalter to come down from the Byzantine Empire."[3] He further writes, "Before entering upon this historiographical discussion the manuscript itself should be introduced. In recent years this Psalter has come to be known as the Theodore Psalter, a name that memorializes the scribe mentioned in the manuscript's colophon, (folio 208r). In its modern binding, the manuscript is 208 folios in length and gathered into twenty-six quires. Each quire is numbered in the lower margin of its opening folio (except where cut) in carmine and black and on the final folio in black."[2]

He goes on to say, "This essay will introduce a number of the various approaches that have been brought to bear upon this work. In reviewing these wide-ranging approaches it will be possible both to define the questions that have shaped the reception of this work and to formulate some possibilities for future research."[2]

Colophon of the Theodore Psalter--MS 19352, f 208

The Psalter

The Psalms are written in metered verse, or twelve-syllable poetic lines, and are thought to be musical. They have been compared to a harp, or other instruments of music.[1] Byzantine psalters stand out in historically because of the artistic qualities the Byzantine Empire was known for. This includes images and icons painted by hand. The art within the Byzantine psalters were specifically unique because of the history surrounding the creation and use of images two centuries before during opposition to icons in the Iconoclastic controversy.[4]

A psalter is a book made specifically to contain the 150 psalms from the book of Psalms. Psalters have also included the odes or canticles, which are songs or prayers in song form from the Old Testament. Psalters were created purely for liturgical purposes, and the Psalms were the most popular books of the Old Testament in Byzantium.[1]

The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium observed, "Like a garden, the book of Psalms contains, and puts in musical form everything that is to be found in other books, and shows, in addition, its own particular qualities."[5]: 1752 Additionally, psalters could be used as a form of guided prayer or meditation.[1]

Theodore the Scribe

Barber wrote in "Essay One" of the Theodore Psalter E-Facsimile,

"The prayer of dedication and the colophon found that the final opening of the manuscript (folios 207v-208r) provide precise information on the production of this manuscript."[3]The colophon, or the place where the information on the body of work, is written on folio 208r and can be translated as follows: "This volume of the divine Psalms was completed in the month of February of the fourth indiction of the year 6574 [i.e. 1066 C.E.] on the order of the divinely inspired felker and synkellos Michael, abbot of the all-holy and all-blessed monastery."[3]

Barber added, "The name of the monastery is lost, but from other evidence within the manuscript we know that it was the Stoudios Monastery in Constantinople."[3] The second part of the colophon reads,

"Written and written in gold by the hand of Theodore the protopresbyter of this monastery and scribe from Caesarea, whose shepherd and luminary was the glorious and brilliant Basil, who was truly great and was also so named."[3]

The Stoudios Monastery was known for its rigorous academic and artistic excellence. A protopresbteros, is an archpriest -- a kind of clerk and monk.[1]

Liturgy and the Psalms

The Byzantine Empire witnessed a very prolific movement in the creation of art.[4] The legalization of Christianity by Emperor Constantine in 313 inspired works of art linked to this religious movement, specifically icons, and they became very popular, and the quintessential art from Byzantine.[4] Church services created and inspired by religious devotion were called liturgical services.[5]: 1240 Liturgy was the concept behind icons, ceremonies or rituals, and the creation of religious books. The act of reading the Psalms was not new. It was thought that icons created a mental universe for the reader imbued with images derived from texts.[6] Art History Professor Herbert L. Kessler believes such manuscripts were created to transport the reader to a different place, a place with high spiritual aspirations.[7]

Illustrations and Images

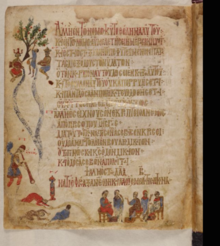

The Theodore Psalter features 440 miniatures, or illustrations. They are ‘marginal’ miniatures; they appear in the margins of the book. The miniatures include illustrations from the Gospels, liturgical illustrations and hagiographical miniatures, or stories about Christ.[5]: 2046 The word miniature means illustration, and originates with the word minium, which had nothing to do with size or the word ‘minimum’. Instead the word refers to the red lead of the pencils used in the 9th Century for these psalters. Throughout the psalter there are both red and blue lines connecting the miniatures to text, much like the way we today link text to photos or other websites.

The Theodore Psalter miniatures convey allegorical meaning from the Psalms or the Odes, and have "an extra layer of meaning supplied by images displaying vigorous anti-Iconoclastic propaganda".[5]: 1753

There are animals and men playing music, birds and vegetation. Art historian and Stanford professor Bissera Pentcheva points out that the icon must be experienced with the senses:

"Focusing on the Byzantine icon, this study plunges into the realm of senses and performative objects. To us, the Greek word for icon, designates portraits of Christ, Mary, angels, saints, and prophets painted in encaustic or tempera on wooden boards. By contrast, eikon in Byzantium had a wide semantic spectrum ranging from hallowed bodies permeated by the Spirit, such as the Stylite saintes or the Eucharist, to imprinted images on the surfaces of metal, stone, and earth. Eikon designated matter imbued with divine pneuma, releasing charis, or grace. As matter, this object was meant to be physically experienced. Touch, smell, taste, and sound were part of “seeing” an eikon.”[8]

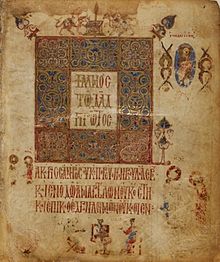

Text and Script

There are two kinds of script used in the Theodore Psalter. One is called majuscule, and is a kind of calligraphy consisting of large or upper case letters. In the Theodore Psalter the majuscule lettering appears in gold. The other kind of text or script used in the manuscript is a smaller text called miniscule. It is also a kind of calligraphy established in the 8th and 9th century by Charlemagne and revived during the Italian Renaissance. Miniscule is the foundational script that forms the basis of the present day Roman upper and lower case type. These small letters appear in red and gold throughout the text, and the cover has those same colors in majuscule.

Professor Barber adds, "the predominant script is a minuscule perlschrift typical of the eleventh century. A gilded majuscule is used for emphasized passages and titles. The text is written beneath the ruled line in brown ink, although certain passages, titles, and initial letters of Psalm verses are written in gold on carmine ink. A varied system of marks in carmine or blue link text and image in this manuscript." Barber adds that the (ruling) patterns are uncommon. "The text block is ruled for a single column of text and measures approximately 10.6 cm by 15.2 cm."[9]

Combinations of Art and Text in the Theodore Psalter

The relationship of icons and text, especially religious text, is an ongoing topic of interest to scholars.

Professor Liz James writes: "Art and text, the interface between images and words, is one of the oldest issues in art history. Are works of art and writings different but parallel forms of expression? Are they intertwined and interdependent?"

"Can art ever stand alone and apart from text or is it always enmeshed in the meanings expressed in the written and the oral that make it perpetually exposed to subjective interpretation? Byzantium was a culture in which the interactions between word and image underpinned, in many ways, the whole meaning of art. For the Byzantines, as a People of the Book, the interface between images and words, and, above all, Christ, the Word of God, was crucial. The dynamic between art and text in Byzantium is essential for understanding Byzantine society, where the correct relationship between the two was critical to the well being of the state."[10]

British Library

The Theodore Psalter is now in the British Library in London. A great deal of work has gone into preserving and digitizing this psalter, now almost a thousand years old.[11]

References

- ^ a b c d e A. P.Kazhdan - Alice-Mary MaffryTalbot - Anthony Cutler - Timothy E.Gregory - Nancy PattersonŠevčenko (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantine. Oxford University, U.K.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195046526.

- ^ a b c d Barber, Charles (February 5, 2000). "Theodore Psalter E-Facsimile". University of Illinois Press.

- ^ a b c d e Barber, Charles (February 5, 2001). Theodore Psalter E-Facsimile. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. Essay. ISBN 978-0252025853.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c Cormack, Robin (November 26, 2000). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, U.K. ISBN 978-0195046526.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b c d Alexander P. Kazhdan, ed. (1991). The Oxford dictionary of Byzantium (1. print. ed.). New York [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0195046526.

- ^ Hawkes-Teeples, Steven; Groen, Bert; Alexopoulos, Stefanos (2013). Studies on the liturgies of the Christian east : selected papers of the Third International Congress of the Society of Oriental Liturgy, Volos, May 26-30, 2010. Leuven: Peeters. p. 228. ISBN 9789042927490.

- ^ Kessler, Herbert L. (2001). Seeing Medieval Art. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-1551115351.

- ^ Pentcheva, Bissera (2013). Sensual icon : space, ritual, and the senses in byzantium. University Park: Penn State Univ Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780271035833.

- ^ Barber, Charles (February 5, 2001). Theodore Psalter E-Facsimile. Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. Essay One. ISBN 978-0252025853.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ James, edited by Liz (2007). Art and text in Byzantine culture (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780521834094.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Digitised Manuscripts - Add MS 19352". British Library. Retrieved 2015-03-07.