Forensic photography

Forensic photography, sometimes referred to as forensic imaging or crime scene photography, is the art of producing an accurate reproduction of a crime scene or an accident scene using photography for the benefit of a court or to aid in an investigation. It is part of the process of evidence collecting. It provides investigators with photos of victims, places and items involved in the crime. Pictures of accidents show broken machinery, or a car crash, and so on. Photography of this kind involves choosing correct lighting, accurate angling of lenses, and a collection of different viewpoints. Scales, like items of length measurement or objects of known size, are often used in the picture so that dimensions of items are recorded on the image.

Feature of crime scene photography

Crime scene photography is very different from many other types of photography. Creative and artistic photography often follow very different rules, which is perfectly fine. But crime scene photography differs from other variations of photography Crime scene photography serves several purposes.

For those who were at the original crime scene, these images will help refresh their memory after a period of time has gone by. For those who could not be present at the original crime scene, it provides them with the opportunity to see the crime scene and the evidence within the crime scene.

This purpose can apply to other law enforcement professionals who will become involved with the case and will later apply when the case goes to trial. The judge, jury, attorneys, and witnesses can all benefit from seeing the original crime scene images. And sometimes the images captured at the crime scene may be one way to actually walk away from the crime scene with the evidence. Often, photography is the only way to actually collect the evidence. Therefore, crime scene photography is a method to: 1. Document the crime scene and the evidence within the crime scene. 2. Collect the evidence. These images can then be later used as examination-quality photographs by experts/analysts from the forensic laboratory.[1]

Crime scene evidences

Crime scene is the source of the physical evidence that is used to associate or link suspects to scenes, victims to scenes, and suspects to victims. Any item found at a crime scene can be physical evidence; it can be labeled the debris of criminal activity. While there is considerable overlap of identifications of evidence, it can be categorized into the following broad groups based on its origin, composition, or method of creation:

1. Biological evidence—any evidence derived from a living item. Includes physiological fluids, plants, and some biological pathogens.

2. Chemical evidence—any evidence with identifiable chemicals present.

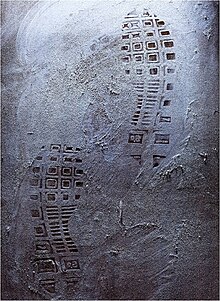

3. Patterned evidence—any evidence with a pattern or predictable pattern of appearance.

4. Trace evidence—any evidence of such a small size so as to be overlooked, not easily seen or not easily recognized.

In addition to identifying the type of physical evidence found at a crime scene it is necessary and possible to obtain valuable investigative information from the analysis of the items of physical evidence.

1.Determination of corpus delicti—the evidence is used to determine if a crime has taken place.

2.Modus operandi identification—criminals repeat behavior. Repeated methods of entry, for example, by kicking in a back door with the same shoe leaving the same footwear impressions throughout the crime scene.

3.Association or linkage—the Locard Exchange Principle—transfer of evidence by contact. See the next section to follow.

4.Disproving/supporting victim/suspect/witness statements—the evidence may or may not support what these groups say.

5.Identification of suspects/victims/crime scene location—fingerprints and even DNA can be used to identify who was present at a crime scene.

6.Provide for investigative leads for detectives—the use of the physical evidence to give information to detectives that will assist them in locating victims and suspects.[2]

Process of initial on- scene

First three activities at the crime scene are essential for the successful preservation of the physical evidence.

1. First Responders at the Crime Scene

The crime scene investigator is rarely the first person at a crime scene. Most first responders work on reflex or instinct at the scene. Their tasks are to save lives or apprehend suspects. Unfortunately, that may mean that physical evidence may be inadvertently altered, changed, or lost due to the actions of a first responder. The crime scene investigator needs to communicate with the first responders to determine if any changes or alterations have occurred at the scene before the scene investigator arrived.

2. Crime Scene Security

Locard Exchange Principle is the basis for the use of physical evidence in a criminal investigation, it is extremely important for the crime scene to be made secure and restrict the access to the crime scene by nonessential people. Many agencies allow easy access to crime scenes by anyone in the agency. Most media persons are kept out but changes to the scene and evidence can change in attempts to protect victims.

3. Preliminary Scene Survey

The preliminary scene survey or walk-through is the crime scene investigator’s first opportunity to view the target area crime scene. A simple visual search for obvious physical evidence can be accomplished at this time. It is during this first viewing of the crime scene that the scene investigator should note any transient or temporary items of evidence and protect them immediately. Melting snow footwear impression are examples of this transient evidence.[3]

Method of Forensic Photography

All photographs must contain three elements: the subject, a scale, and a reference object. Crime scene photographs should always be in focus, with the subject of the photograph as the main object of the scene. There should always be a scale or ruler present. This will allow the investigators the ability to resize the image to accurately reconstruct the scene. The overall photographs must be a fair and accurate representation of what is seen. Any change in color may misidentify an object for investigators and possibly jurors. (Figure 3.0)

Preliminary overall photographs should attempt to capture the locations of evidence and identifying features of the scene, such as addresses, vehicle identification numbers and serial numbers, footwear/tire mark impressions, and the conditions of the scene. While the purpose of the overall photograph is to document the conditions of the scene and the relationship of objects, the medium range photograph serves to document the appearance of an object. In all photographs, a scale must be included, as well as a marker to indicate the identity of the object in question. Again, objects of medium-range photographs must be a fair and accurate representation of what is seen. Adjusting the photographic principles or lighting may allow the photographer to achieve this goal.

In Figure 3.1, Photograph 2 is a correct representation. By adjusting the flash, the reflection from the charring was omitted, allowing the damage to be captured as seen by the investigator.

In general, the basic components of macro or evidentiary photography are as follows: If any evidentiary photographs are to be taken for use in a critical comparison examination at a later time, guidelines must be followed in accordance with the best practices of digital evidence.

1. The digital image must be captured in a lossless compression format. The two widely accepted lossless compression formats are tagged image file format (TIFF) and RAW. TIFF is a universal file type, whereas RAW files are proprietary based upon the manufacturer of the camera. Specialized software may be required to open and enhance a RAW image.

2. The camera must be on a grounded platform, such as a copy stand or tripod. In general, the human body cannot stop natural vibrations with a camera shutter speed slower than 1/60 of a second. Using a grounded platform will allow the subject matter to be in complete focus.

3. The camera shutter must be controlled by a remote cord or by using the timer mode. The simple action of depressing the shutter control will cause the camera to vibrate, losing focus of the subject matter.

Documentation The responding officer must also maintain a photo log if any photographic documentation is taken. The log should contain the date and time of the photograph, the subject matter, and any additional notes. These logs must be maintained within a case file or incident report, as they are a part of the examination record and discoverable material at trial.(Figure 3.2)[4]

Digital Photography Photographers must be cognizant of the principles of photography that will guide the composition of the image itself. When taking the photograph itself, there are three controls to the camera: ISO, shutter speed, and aperture. The ISO setting (International Organization of Standards) controls the “speed” of the film. The shutter speed controls the amount or duration of light that passes through the lens and is captured by the sensor array. Finally, the aperture is the feature of the camera that controls the depth of field, or the depth of focus of the image.(Figure 3.3, 3.4 and 3.5)

In Figure 3.3, High ISO on left, where the image appears “grainy.” Correct ISO on right. Photos are taken at a distance of approximately 150 yards.

(In Figure 3.4, Photograph on the left was underexposed due to the shutter speed being set too fast, when compensated for, and allowed to remain open longer, the shutter speed corrected the exposure of the photograph in the image on the right.

The change in the aperture settings allows the markers in the distance to be in focus as compared to the markers closest to the camera. In Figure 3.6 the evidence markers are arranged in increasing distance from the camera.

Use of Flash

External flash units are helpful tools when responding to a crime scene and for the proper documentation of evidence. The white balance of a photo flash unit is set to mimic daylight to ensure the proper color balance of the subject matter. The photographer must be mindful of the reflections that can occur due to the directionality of the flash and the position of the subject matter. To avoid flash reflections, as demonstrated in Figure 3.7, the flash must either be removed from the camera body, creating an angle, or bounced off of the ceiling.

Figure 3.7, To avoid flash reflections, the flash must either be removed from the camera body, creating an angle, or bounced off of the ceiling. Photo courtesy of Nicholas Petraco.[5]

Equipment

The tools required to properly document the crime scene include:[6]

▪Notepad

▪Clipboard and/or digital tablet device

▪Graph paper

▪Writing instruments (pens, pencils, markers)

▪Still camera with external flash and extra batteries

▪Video camera ▪Tripod

▪Measurement instruments (tape measures, rulers, electronic measuring devices, perspective grids, etc.)

▪Evidence identification and position markers or placards

▪Photographic log

▪Compass

Methods

Feature

Crime scene photography is very different from many other types of photography. Creative and artistic photography often follow very different rules, which is perfectly fine. But crime scene photography differs from other variations of photography because the crime scene photographers usually have a very specific purpose for capturing each image. There is a specific job to be done and specific types of images that have to be captured.[7]

Fit for court

The images must be clear and usually have scales. They serve to not only remind investigators of the scene, but also to provide a tangible image for the court to better enable them to understand what happened. The use of several views taken from different angles helps to minimise the problem of parallax. Overall images do not have scales and serve to show the general layout, such as the house where the murder is thought to have occurred. Context images show evidence in context, like how the knife was next to the sofa. Close up images show fine detail of an artifact, such as a bloody fingerprint on the knife.

Road traffic incident (RTI) photographs show the overall layout at the scene taken from many different angles, with close-ups of significant damage, or trace evidence such as tire marks at a traffic collision. As with crime scene photography, it is essential that the site is pristine and untouched as far as is possible. Some essential intervention, such as rescuing a trapped victim, must be recorded in the notes made at the time by the photographer, so that the authenticity of the photographs can be verified.

As with all evidence a chain of custody must be maintained for crime scene photographs. Sometimes a CSI (forensic photographer) will process his/her own film or there is a specific lab for it. Regardless of how it is done any person who handles the evidence must be recorded. Secure Digital Forensic Imaging methods may be applied to help ensure against tampering and improper disclosure.[8] Accident scene pictures should also be identified and sourced, police photographs taken at the scene often being used in civil cases.

Analysis of historic photographs

Crime or accident scene photographs can often be re-analysed in cold cases or when the images need to be enlarged to show critical details. Photographs made by film exposure usually contain much information which may be crucial long after the photograph was taken. They can readily be digitised by scanning, and then enlarged to show the detail needed for new analysis. For example, controversy has raged for a number of years over the cause of the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879 when a half-mile section of the new bridge collapsed in a storm, taking an express train down into the estuary of the river Tay. At least 75 passengers and crew were killed in the disaster.

The set of photographs taken a few days after the accident have been re-analysed in 1999–2000 by digitising them and enlarging the files to show critical details. The originals were of very high resolution since a large plate camera was used with a small aperture, plus a small grain film. The re-analysed pictures shed new light on why the bridge fell, suggesting that design flaws and defects in the cast iron columns which supported the centre section led directly to the catastrophic failure. Alternative explanations that the bridge was blown down by the wind during the storm that night, or that the train derailed and hit the girders are unlikely. The re-analysis supports the original court of inquiry conclusions, which stated that the bridge was "badly designed, badly built and badly maintained".[9]

See also

- Forensic engineering

- Forensic materials engineering

- Forensic polymer engineering

- Forensic science

- History of forensic photography

- Murder book

- Photography

- Skid mark

- Trace evidence

References

- Farrar, Andrew; Porter, Glenn; Renshaw, Adrian (2012). "Detection of Latent Bloodstains Beneath Painted Surfaces using Reflected Infrared Photography". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 57 (5): 1190–1198. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2012.02231.x. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ Robinson, Edward M. (2013). Introduction to crime scene photography (Online-Ausg. ed.). Oxford, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 1-77. ISBN 9780123865434. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Miller, Marilyn T.; Peter, Massey. Chapter 2 - Initial On-Scene Procedures. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 3-15. ISBN 9780128012451. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Miller, Marilyn T; Peter, Massey. Chapter 1 - Crime Scene Investigations. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 3-15. ISBN 9780128012451.

- ^ Reitnauer, Andrew R. Crime Scene Response and Evidence Collection, In Security Supervision and Management (Fourth ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 443-459. ISBN 9780128001134.

- ^ Reitnauer, Andrew R. 34 - Crime Scene Response and Evidence Collection, In Security Supervision and Management (Fourth ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 443-459. ISBN 9780128001134. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ Fish, Jacqueline T.; Miller, Larry S.; Braswell, Michael C.; Wallace Jr., Edward W. (2014-01-01). Chapter 3 - Documenting the Crime Scene: Photography, Videography, and Sketching. Boston: Anderson Publishing, Ltd. pp. 59–83. ISBN 9781455775408.

- ^ Robinson, Edward M. (2013). Introduction to crime scene photography (Online-Ausg. ed.). Oxford, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 1–77. ISBN 9780123865434.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Lawrence Memorial Hospital sexual assault exam room with SDFI system

- ^ Porter, Glenn (2013). "Images as Evidence". Precedent. 119 (Nov/Dec): 38–42. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

Further reading

- Introduction to Forensic Engineering (The Forensic Library) by Randall K. Noon, CRC Press (1992).

- Forensic Engineering Investigation by Randall K. Noon, CRC Press (2000).

- Forensic Materials Engineering: Case Studies by Peter Rhys Lewis, Colin Gagg, Ken Reynolds, CRC Press (2004).

- Peter R Lewis and Sarah Hainsworth, Fuel Line Failure from stress corrosion cracking, Engineering Failure Analysis,13 (2006) 946-962.

- Peter R. Lewis, Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: Reinvestigating the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879, Tempus, 2004, ISBN 0-7524-3160-9.