Accelerating expansion of the universe

This article provides insufficient context for those unfamiliar with the subject. (April 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

The accelerating expansion of the universe is the observation that the universe appears to be expanding at an increasing rate. In formal terms, this means that the cosmic scale factor has a positive second derivative,[1] so that the velocity at which a distant galaxy is receding from the observer is continuously increasing with time.[2]

In 1998 two independent projects, the Supernova Cosmology Project and the High-Z Supernova Search Team simultaneously obtained results suggesting a totally unexpected acceleration in the expansion of the universe by using distant type Ia supernovae as standard candles.[3][4][5] Three members of these two groups have subsequently been awarded Nobel Prizes for their discovery.[6] Confirmatory evidence has been found in baryon acoustic oscillations and other new results about the clustering of galaxies.

The time the universe expansion began accelerating seems to be when the universe was "... about 7.8 billion years old, or about 6 billion years ago, some 1.5 billion years before our Solar System formed.", according to astrophysicist Ethan Siegel,[7] although astronomer Joshua Frieman of CalTech notes, "the Universe began accelerating at redshift z ~ 0.4 and age t ~ 10 Gyr."[8] [Note: "9.4" Gyr? determined using a cosmological calculator.[9]]

Mechanism

Being more dense than the ambient photon bath, protons collapse increasingly faster than the latter, which increases their apparent separation (a massive object's free-fall timescale tff is inversely proportional to the object's density ρ):

- (13.8)

Equation (13.8) implies that the denser clumps collapse more rapidly, which may lead to separation and fragmentation. As cores are observed to be densest near their centers, the interiors cave in most quickly, producing an inside-out collapse.[10]

Background

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Since Hubble's discovery of the expansion of the universe in 1929,[11] the Big Bang model has become the accepted explanation for the origin of our universe. The Friedmann equation defines how the energy in the universe drives its expansion.

where represents the curvature of the universe, is the scale factor, is the total energy density of the universe, and is the Hubble parameter.[12]

We define a critical density

and the density parameter

We can then rewrite the Hubble parameter as

where the four currently hypothesized contributors to the energy density of the universe are curvature, matter, radiation and dark energy.[13] Each of the components decreases with the expansion of the universe (increasing scale factor), except perhaps the dark energy term. It is the values of these cosmological parameters which physicists use to determine the acceleration of the universe.

The acceleration equation describes the evolution of the scale factor with time

where the pressure P is defined by the cosmological model chosen. (see explanatory models below)

Physicists at one time were so assured of the deceleration of the universe's expansion that they introduced a so-called deceleration parameter .[14] Current observations point towards this deceleration parameter being negative.

Evidence for acceleration

To learn about the rate of expansion of the universe we look at the magnitude-redshift relationship of astronomical objects using standard candles, or their distance-redshift relationship using standard rulers. We can also look at the growth of large-scale structure, and find that the observed values of the cosmological parameters are best described by models which include an accelerating expansion.

Supernova observation

The first evidence for acceleration came from the observation of Type Ia supernovae, which are exploding white dwarfs that have exceeded their stability limit. Because they all have similar masses, their intrinsic luminosity is standardizable. Repeated imaging of selected areas of sky is used to discover the supernovae, then follow-up observations give their peak brightness, which is converted into a quantity known as luminosity distance (see distance measures in cosmology for details).[15] Spectral lines of their light can be used to determine their redshift.

For supernovae at redshift less than around 0.1, or light travel time less than 10 percent of the age of the universe, this gives a nearly linear distance-redshift relation due to Hubble's law. At larger distances, since the expansion rate of the universe has changed over time, the distance-redshift relation deviates from linearity, and this deviation depends on how the expansion rate has changed over time. The full calculation requires integration of the Friedmann equation, but a simple derivation can be given as follows: the redshift z directly gives the cosmic scale factor at the time the supernova exploded.

So a supernova with a measured redshift z = 0.5 implies the universe was 1/(1+0.5) = 2/3 of its present size when the supernova exploded. In an accelerating universe, the universe was expanding more slowly in the past than it is today, which means it took a longer time to expand from 2/3 to 1.0 times its present size compared to a non-accelerating universe. This results in a larger light-travel time, larger distance and fainter supernovae, which corresponds to the actual observations. Riess found that "the distances of the high-redshift SNe Ia were, on average, 10% to 15% farther than expected in a low mass density universe without a cosmological constant".[16] This means that the measured high-redshift distances were too large, compared to nearby ones, for a decelerating universe.[17]

Baryon acoustic oscillations

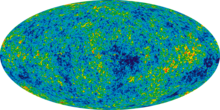

In the early universe before recombination and decoupling took place, photons and matter existed in a primordial plasma. Points of higher density in the photon-baryon plasma would contract, being compressed by gravity until the pressure became too large and they expanded again.[14] This contraction and expansion created vibrations in the plasma analogous to sound waves. Since dark matter only interacts gravitationally it stayed at the centre of the sound wave, the origin of the original overdensity. When decoupling occurred, approximately 380,000 years after the Big Bang,[18] photons separated from matter and were able to stream freely through the universe, creating the cosmic microwave background as we know it. This left shells of baryonic matter at a fixed radius from the overdensities of dark matter, a distance known as the sound horizon. As time passed and the universe expanded, it was at these anisotropies of matter density where galaxies started to form. So by looking at the distances at which galaxies at different redshifts tend to cluster, it is possible to determine a standard angular diameter distance and use that to compare to the distances predicted by different cosmological models.

Peaks have been found in the correlation function (the probability that two galaxies will be a certain distance apart) at 100h Mpc,[13] indicating that this is the size of the sound horizon today, and by comparing this to the sound horizon at the time of decoupling (using the CMB), we can confirm that the expansion of the universe is accelerating.[19]

Clusters of galaxies

Measuring the mass functions of galaxy clusters, which describe the number density of the clusters above a threshold mass, also provides evidence for dark energy.[20] By comparing these mass functions at high and low redshifts to those predicted by different cosmological models, values for and are obtained which confirm a low matter density and a non zero amount of dark energy.[17]

Age of the universe

Given a cosmological model with certain values of the cosmological density parameters, it is possible to integrate the Friedmann equations and derive the age of the universe.

By comparing this to actual measured values of the cosmological parameters, we can confirm the validity of a model which is accelerating now, and had a slower expansion in the past.[17]

Explanatory models

Dark energy

The most important property of dark energy is that it has negative pressure which is distributed relatively homogeneously in space.

where c is the speed of light, is the energy density. Different theories of dark energy suggest different values of w, with w < -1/3 for cosmic acceleration (this leads to a positive value of in the acceleration equation above).

The simplest explanation for dark energy is that it is a cosmological constant or vacuum energy; in this case w = -1. This leads to the Lambda-CDM model, which has generally been known as the Standard Model of Cosmology from 2003 through the present, since it is the simplest model in good agreement with a variety of recent observations. Riess found that their results from supernovae observations favoured expanding models with positive cosmological constant ( > 0) and a current acceleration of the expansion ( < 0).[16]

Phantom energy

Current observations allow the possibility of a cosmological model containing a dark energy component with equation of state:

This phantom energy density would become infinite in finite time, causing such a huge gravitational repulsion that the universe would lose all structure and end in a Big Rip.[21] For example, for w = -3/2 and = 70 km·s−1·Mpc−1, the time remaining before the universe ends in this "Big Rip" is 22 billion years.[22]

Alternative theories

Other explanations for the accelerating universe include quintessence, a proposed form of dark energy with a non-constant state equation, whose density decreases with time. Dark fluid is an alternative explanation for accelerating expansion which attempts to unite dark matter and dark energy into a single framework.[23] Alternatively, some authors have argued that the universe expansion acceleration could be due to a repulsive gravitational interaction of antimatter.[24][25][26]

Another type of model, the backreaction conjecture,[27][28] was proposed by cosmologist Syksy Räsänen:[29] the rate of expansion is not homogenous, but we are in a region where expansion is faster than the background. Inhomogeneities in the early universe cause the formation of walls and bubbles, where the inside of a bubble has less matter than on average. According to general relativity, space is less curved than on the walls, and thus appears to have more volume and a higher expansion rate. In the denser regions, the expansion is retarded by a higher gravitational attraction. Therefore, the inward collapse of the denser regions looks the same as an accelerating expansion of the bubbles, leading us to conclude that the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate.[30] The benefit is that it does not require any new physics such as dark energy. Räsänen does not consider the model likely, but without any falsification, it must remain a possibility. It would require rather large density fluctuations (20%) to work.[29]

Theories for the consequences to the universe

As the universe expands, the density of radiation and ordinary and dark matter declines more quickly than the density of dark energy (see equation of state) and, eventually, dark energy dominates. Specifically, when the scale of the universe doubles, the density of matter is reduced by a factor of 8, but the density of dark energy is nearly unchanged (it is exactly constant if the dark energy is a cosmological constant).[14]

In models where dark energy is a cosmological constant, the universe will expand exponentially with time from now on, coming closer and closer to a de Sitter spacetime. This will eventually lead to all evidence for the Big Bang disappearing, as the cosmic microwave background is redshifted to lower intensities and longer wavelengths. Eventually its frequency will be low enough that it will be absorbed by the interstellar medium, and so be screened from any observer within the galaxy. This will occur when the universe is less than 50 times its current age, leading to the end of cosmology as we know it as the distant universe turns dark.[31]

Alternatives for the ultimate fate of the universe include the Big Rip mentioned above, a Big Bounce, Big Freeze, or Big Crunch.

See also

References

- ^ Jones, Mark H.; Robert J. Lambourne (2004). An Introduction to Galaxies and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-521-83738-5.

- ^ Is the universe expanding faster than the speed of light? (see final paragraph)

- ^ "Nobel physics prize honours accelerating universe find". BBC News. October 4, 2011.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2011". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ^ Peebles, P. J. E.; Ratra, Bharat (2003). "The cosmological constant and dark energy". Reviews of Modern Physics. 75 (2): 559–606. arXiv:astro-ph/0207347. Bibcode:2003RvMP...75..559P. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.559.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Cosmology, Steven Weinberg, Oxford University Press, 2008

- ^ Siegel, Ethan (August 29, 2014). "Ask Ethan #52: How long has the Universe been accelerating?". Medium (website). Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Frieman, Joshau A.; Turner, Michael S.; Huterer, Dragan. "Dark Energy and the Accelerating Universe" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. arXiv:0803.0982v1. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Staff. "Cosmological Calculator". Fermilab. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Pater, Imke de; Lissauer, Jack J. Planetary Sciences Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 518

- ^ Hubble, Edwin (1929). "A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae". PNAS. 15 (3): 168–173. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. PMC 522427. PMID 16577160.

- ^ Nemiroff, Robert J.; Patla, Bijunath. "Adventures in Friedmann cosmology: A detailed expansion of the cosmological Friedmann equations". American Journal of Physics. 76 (3): 265. arXiv:astro-ph/0703739. Bibcode:2008AmJPh..76..265N. doi:10.1119/1.2830536.

- ^ a b Lapuente, P.. "Baryon Acoustic Oscillations." Dark energy: observational and theoretical approaches. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- ^ a b c Ryden, Barbara. "Introduction to Cosmology." Physics Today: 77. Print.

- ^ Albrecht, A., Bernstein, G., Cahn, R., et al. Report of the Dark Energy TaskForce. ArXiv Astrophysics e-prints, September 2006.

- ^ a b Riess, Adam G.; Filippenko, Alexei V.; Challis, Peter; Clocchiatti, Alejandro; Diercks, Alan; Garnavich, Peter M.; Gilliland, Ron L.; Hogan, Craig J.; Jha, Saurabh; Kirshner, Robert P.; Leibundgut, B.; Phillips, M. M.; Reiss, David; Schmidt, Brian P.; Schommer, Robert A.; Smith, R. Chris; Spyromilio, J.; Stubbs, Christopher; Suntzeff, Nicholas B.; Tonry, John. "Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant". The Astronomical Journal. 116 (3): 1009–1038. arXiv:astro-ph/9805201. Bibcode:1998AJ....116.1009R. doi:10.1086/300499.

- ^ a b c Pain, Reynald. "Observational evidence of the accelerated expansion of the Universe." Comptes Rendus Physique: 521-538. [1]

- ^ Hinshaw, G. (2014). "Five-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Data Processing, Sky Maps, and Basic Results". Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 180: 225–245. arXiv:0803.0732. Bibcode:2009ApJS..180..225H. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/180/2/225.

- ^ Eisenstein, Daniel J.; Zehavi, Idit; Hogg, David W.; Scoccimarro, Roman; Blanton, Michael R.; Nichol, Robert C.; Scranton, Ryan; Seo, Hee‐Jong; Tegmark, Max; Zheng, Zheng; Anderson, Scott F.; Annis, Jim; Bahcall, Neta; Brinkmann, Jon; Burles, Scott; Castander, Francisco J.; Connolly, Andrew; Csabai, Istvan; Doi, Mamoru; Fukugita, Masataka; Frieman, Joshua A.; Glazebrook, Karl; Gunn, James E.; Hendry, John S.; Hennessy, Gregory; Ivezić, Zeljko; Kent, Stephen; Knapp, Gillian R.; Lin, Huan; Loh, Yeong‐Shang; Lupton, Robert H.; Margon, Bruce; McKay, Timothy A.; Meiksin, Avery; Munn, Jeffery A.; Pope, Adrian; Richmond, Michael W.; Schlegel, David; Schneider, Donald P.; Shimasaku, Kazuhiro; Stoughton, Christopher; Strauss, Michael A.; SubbaRao, Mark; Szalay, Alexander S.; Szapudi, Istvan; Tucker, Douglas L.; Yanny, Brian; York, Donald G. (10 November 2005). "Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large‐Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies". The Astrophysical Journal. 633 (2): 560–574. arXiv:astro-ph/0501171. Bibcode:2005ApJ...633..560E. doi:10.1086/466512.

- ^ Dekel, Avishai. Formation of structure in the Universe. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ^ Caldwell, Robert; Kamionkowski, Marc; Weinberg, Nevin (August 2003). "Phantom Energy: Dark Energy with w-1 Causes a Cosmic Doomsday". Physical Review Letters. 91 (7): 071301. arXiv:astro-ph/0302506. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..91g1301C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.071301. PMID 12935004.

- ^ Caldwell, R.R. "A phantom menace? Cosmological consequences of a dark energy component with super-negative equation of state". Physics Letters B. 545 (1–2): 23–29. arXiv:astro-ph/9908168. Bibcode:2002PhLB..545...23C. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(02)02589-3.

- ^ Anaelle Halle, HongSheng Zhao, Baojiu Li (2008) "Perturbations in a non-uniform dark energy fluid: equations reveal effects of modified gravity and dark matter [2]"

- ^ A. Benoit-Lévy and G. Chardin, Introducing the Dirac-Milne universe, Astronomy and Astrophysics 537, A78 (2012)

- ^ D.S. Hajdukovic, Quantum vacuum and virtual gravitational dipoles: the solution to the dark energy problem?, Astrophysics and Space Science 339(1), 1--5 (2012)

- ^ M. Villata, On the nature of dark energy: the lattice Universe, 2013, Astrophysics and Space Science 345, 1. Also available here

- ^ "Backreaction: directions of progress". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 28: 164008. arXiv:1102.0408. Bibcode:2011CQGra..28p4008R. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/28/16/164008.

- ^ "Backreaction in Late-Time Cosmology". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science. 62: 57–79. arXiv:1112.5335. Bibcode:2012ARNPS..62...57B. doi:10.1146/annurev.nucl.012809.104435.

- ^ a b https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn11498-is-dark-energy-an-illusion/

- ^ "A Cosmic 'Tardis': What the Universe Has In Common with 'Doctor Who'". Space.com.

- ^ Krauss, Lawrence M.; Scherrer, Robert J. (28 June 2007). "The return of a static universe and the end of cosmology". General Relativity and Gravitation. 39 (10): 1545–1550. arXiv:0704.0221. Bibcode:2007GReGr..39.1545K. doi:10.1007/s10714-007-0472-9.