SEPTA Regional Rail

| |

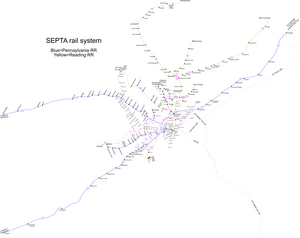

SEPTA Regional Rail system map | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Stations called at | 153 |

| Headquarters | 1234 Market Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 |

| Reporting mark | SEPA (revenue equipment), SPAX (non-revenue and MOW equipment) |

| Locale | Delaware Valley |

| Dates of operation | 1983–present |

| Predecessor | Conrail |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Other | |

| Website | www.septa.org |

The SEPTA Regional Rail system (reporting marks SEPA, SPAX) consists of commuter rail service on 13 branches to more than 150 active stations in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and its suburbs and satellite cities. Service on most lines operates from 5:30 a.m. to midnight. It is the fifth-busiest commuter railroad in the United States and busiest outside of the New York and Chicago metropolitan areas. In 2016, Regional Rail had an average of 132,000 daily riders.[1]

The core of the Regional Rail system is the Center City Commuter Connection, composed of three Center City stations in the "tunnel" corridor: the above-ground upper level of 30th Street Station, the underground Suburban Station, and Jefferson Station (formerly Market East Station). All trains stop at these Center City stations; most also stop at Temple University station on the campus of Temple University in North Philadelphia. Operations are handled by the SEPTA Railroad Division.[2]

Of the 13 branches, seven were originally owned and operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) (later Penn Central), and six by the Reading Company (RDG). The PRR lines terminated at Suburban Station; the RDG lines at Reading Terminal. In November 1984, the Center City Commuter Connection united the two systems, turning the two terminal stations (Reading Terminal having been replaced by the Jefferson Station) into through-stations. Most inbound trains from one line continue on as outbound trains on another line. (Some limited or express trains, and all trains on the Cynwyd Line, terminate on one of the stub-end tracks at Suburban Station.)

Lines

Each PRR line was once paired with a RDG branch and numbered from R1 to R8 (except for R4), so that one route number described two lines, one on the PRR side and one on the RDG side. This was ultimately deemed more confusing than helpful, so on July 25, 2010, SEPTA dropped the R-number and color-coded route designators and changed dispatching patterns so fewer trains follow both sides of the same route.[3]

- Former Pennsylvania Railroad lines

- Airport Line: terminates at the Philadelphia International Airport.

- Chestnut Hill West Line: terminates in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia.

- Cynwyd Line: terminates in Cynwyd and operates weekdays only. Until 1986, trains continued on to Ivy Ridge station in northwestern Philadelphia.

- Media/Elwyn Line: terminates in Elwyn. Until 1986, trains continued on to West Chester. SEPTA is considering restoring service to Wawa, approximately three miles (5 km) west of Elwyn; this project is on hold due to lack of funding.[4]

- Paoli/Thorndale Line: trains terminate at Malvern or Thorndale; additional rush hour trains terminate at Bryn Mawr.

- Trenton Line: terminates in Trenton, New Jersey. This line uses Amtrak's Northeast Corridor, and offers a connection at Trenton to New Jersey Transit's Northeast Corridor Line for continued service to New York City.

- Wilmington/Newark Line: terminates in Wilmington, Delaware, with some weekday trains continuing to Newark, Delaware. The Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT) subsidizes Delaware service. This line runs entirely on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.

- Former Reading Company lines

- Chestnut Hill East Line: terminates in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia.

- Fox Chase Line: terminates in the Fox Chase section of Philadelphia. Until 1983, connecting diesel trains continued to Newtown, Pennsylvania.

- Lansdale/Doylestown Line: terminates at Doylestown. On weekdays, approximately half of the local trains terminate at Lansdale while the remainder of the local trains, and some expresses, continue on to Doylestown.

- Manayunk/Norristown Line: terminates at Elm Street in Norristown.

- Warminster Line: terminates in Warminster.

- West Trenton Line: terminates at the West Trenton station in Ewing, New Jersey.

Stations

There are 154 active stations on the Regional Rail system (as of 2016), including 51 in the city of Philadelphia, 42 in Montgomery County, 29 in Delaware County, 16 in Bucks County, 10 in Chester County, and six outside the state of Pennsylvania. In 2003, passengers boarding in Philadelphia accounted for 61% of trips on a typical weekday, with 45% from the three Center City stations and Temple University station.

| County | Stations | Boardings in 2003 | Boardings in 2001 |

| Philadelphia | 51 | 60 967 | 61 970 |

| Montgomery County | 42 | 17 228 | 18 334 |

| Delaware County | 29 | 8 310 | 8 745 |

| Bucks County | 16 | 5 332 | 5 845 |

| Chester County | 10 | 5 154 | 5 079 |

| Outside Pennsylvania | 6 | 2 860 | 3 423 |

| total | 154 | 99 851 | 103 396 |

Rolling stock

SEPTA uses a mixed fleet of General Electric and Hyundai Rotem "Silverliner" electric multiple unit (EMU) cars, used on all Regional Rail lines. SEPTA also uses push-pull equipment: coaches built by Bombardier and Pullman Standard, hauled by AEM-7 or ALP-44 (and soon to be ACS-64) electric locomotives similar to those used by Amtrak and New Jersey Transit (NJT) respectively. The push-pull equipment is used primarily for peak express service because it accelerates slower than EMU equipment, making it less suitable for local service with close station spacing and frequent stops and starts.

As of 2012, all cars have a blended red-and-blue SEPTA window logo and "ditch lights" that flash at grade crossings and when "deadheading" through stations, as required by Amtrak for operations on the Northeast and Keystone Corridors. SEPTA's railroad reporting mark SEPA is the official mark for their revenue equipment, though it is rarely seen on external markings. SPAX can be seen on non-revenue work equipment, including boxcars, diesel locomotives, and other rolling stock.

The "Silverliner" coaches, built by Budd in Philadelphia and first used by the PRR in 1958 as the "Pioneer III" for a prototype intercity EMU alternative to the GG1-hauled trains, were purchased by SEPTA in 1963 as "Silverliner II" units. In 1967, the PRR took delivery of the St. Louis-built "Silverliner III" cars, which featured left-hand side controls (railroad cars traditionally have right-hand side controls) and flush toilets (since removed), and were used primarily for Harrisburg-Philadelphia service. The Silverliner II and III cars were designated under the PRR MP85 class. Some "Silverliner III" cars were converted for exclusive Airport Line use; they featured special luggage racks where the old toilet closets were located, yellow window paintings, and the Philadelphia International Airport's "PHL" logo. The bulk of the fleet are "Silverliner IV" coaches built by General Electric in Erie with carshells from Avco and Canadian Vickers; these were delivered in 1973–76, before the formation of Conrail.

In 1990, the Reading-era "Blueliner" and PRR-era Pioneer III/Silverliner I coachers were retired. In 2002, SEPTA announced the building of 104 new "Silverliner V" cars to replace the "Silverliner II" and "Silverliner III". SEPTA retired the "Silverliner II" and "Silverliner III" cars in June 2012 and replaced them with the "Silverliner V" model. A total of 120 new "Silverliner V" cars were built, with the first three entering service on October 29, 2010.[5] The cost for all 120 cars is $274 million, and they were constructed in facilities located in South Philadelphia and South Korea by Hyundai Rotem.[5][6] The cars were build with wider seats and a center-opening door for easier boarding or departing at high-level stations in Center City. As of March 2013, all 120 cars have been delivered, and are in service.

All Silverliner models are compatible with one another, now that the "Pioneer III" (Silverliner I) coaches have been scrapped. (One survived on display at the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania in nearby Strasburg.)

SEPTA also owns two "Arrow II" EMU cars built by GE in 1974 and once operated by New Jersey Transit for its electrified service to and from New York City and Hoboken Terminal (formerly NJT 1236 and 1237). The "Arrow II" car is nearly identical to that of the "Silverliner IV", but lacks the distinctive dynamic brake roof "hump" on the car, and has a "diamond" pantograph instead of the "T" pantograph used on the "Silverliner". The "Arrow II" are used as part of work trains, such as catenary inspection and leaf removal.

The entire system uses 12,000-volt/25 Hz overhead catenary lines that were erected by the PRR and RDG railroads between 1915 and 1938. All current SEPTA equipment is compatible with the power supplies on both the ex-PRR (Amtrak-supplied) and ex-RDG (SEPTA-supplied) sides of the system; the "phase break" is at the northern entrance to the Center City commuter tunnel between Jefferson Station and Temple University Station.

In late 2014, and the beginning of early 2015, SEPTA began the "Rebuilding for the Future" campaign that will replace all deteriorated rolling stock and rail lines with new, modernized, equipment, including ACS-64s, bi-level cars, and better signaling.

-

SEPTA train 256 in 1974

-

SEPTA train 213 in 1974

-

Silverliner II No. 269 still carrying "PENNSYLVANIA" name plates.

-

Eastbound SEPTA 145 making a station stop in Paoli, in 1993.

-

Train of Silverliner II and III cars entering the Temple University Station in May 2006.

-

SEPTA AEM-7 engine 2301 enters the Temple University station.

-

GE Silverliner IV at 30th Street Station.

-

Rotem Silverliner V at Saint Martins Station.

SEPTA passenger rolling stock includes:

Electric multiple units

| Year | Make | Model | Numbers[7] | Total | Hp | Tare (Ton/t) |

Seats | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973–76 | GE | Silverliner IV | 101–188, 306–399, 417–460 (married pairs) 276–305, 400–416 (single cars) |

231 of 232 active | Not known | 62.5/56.8 | 125 | 101–188 Series Former Reading Married Pairs. 306–399 Series Former Penn Central Married Pairs. 400-series units are cars renumbered from lower series or from Reading Railroad cars 9018–9031 when PCB transformers were replaced with silicone transformers. |

| 2010–13 | Rotem | Silverliner V | 701–738 (single cars) 801–882 (married pairs) |

120 of 120 active | 62.5/56.8 | 110 | Replacements for 70 older cars; will also add capacity.[6] First three cars entered revenue service October 29, 2010; delivery completed as of March 21, 2013. |

Push-pull passenger cars

| Year | Make | Model | Numbers[7] | Total | Tare (Ton/t) |

Seats | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Pullman Standard | Comet I | 2460–2461(cab cars) 2590–2595 (trailers) |

2 cabs, 6 coaches | 50/45.4 | 118 (cab car) 131 (trailers) |

Cars originally built for NJDOT for service on the Erie Lackawanna's commuter trains. Purchased from NJ Transit 2008 for added seating. As of August 2013 they were put in storage. |

| 1987 | Bombardier | SEPTA I | 2401–2410 (cab cars) 2501–2525 (trailers) |

10 cab cars 25 trailers |

50/45.4 | 118 (cab cars) 131 (trailers) |

|

| 1999 | Bombardier | SEPTA II | 2550–2559 | 10 trailers | 50/45.4 | 117 | These cars have a center door. |

According to SEPTA's "Rebuilding for the Future" webpage, the agency is exploring the use of bi-level passenger cars in its push-pull fleet upon retirement of the Bombardier cars.

Locomotives

| Year | Make | Model | Numbers[7] | Total | Hp | Tare (Ton/t) |

Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | EMD | AEM-7 | 2301–2307 | 7 | 7,000 | 101/91.9 | *Will be replaced by ACS-64. |

| 1995 | ABB | ALP-44 | 2308 | 1 | 7,000 | 99.2/90.2 | Delivered as a result of a settlement agreement for late delivery of N-5 cars. Will be replaced by ACS-64. |

| 2018 | Siemens | ACS-64 | TBD | 13 | 8,600 | 107.5/97.6 | To replace AEM-7 and ALP-44 fleet.[8] |

Electrification

All lines used by SEPTA are electrified with overhead catenary supplying alternating current at 12 kV with a frequency of 25 Hz. The system on the former PRR side is owned and operated by Amtrak, part of the electrification of the Northeast Corridor. The electrification on the RDG side is owned by SEPTA. The Amtrak system was originally built by the PRR between 1915 and 1938. The SEPTA-owned system was originally built by the RDG starting in 1931.

Yards and maintenance facilities

SEPTA has four major yards and facilities for the storage and maintenance of regional rail trains:

- Frazer Yard, in Frazer, Pennsylvania, along the Paoli/Thorndale Line; services push-pull train sets.

- Overbrook Maintenance Facility, near Overbrook station on the Paoli/Thorndale Line; Services EMUs

- Powelton Yard, adjacent to 30th Street Station

- Roberts Yard, adjacent to Wayne Junction

History

SEPTA was created to prevent passenger railroads and other mass transit services from disappearing or shrinking in the region. Passenger rail service was previously provided by for-profit companies, but by the 1960s the profitability had eroded, not least because huge growth of automobile use over the previous 30 years had reduced ridership. SEPTA's creation provided government subsidies to such operations and thus kept them from closing down. For the railroads, at first it was a matter of paying the existing railroad companies to continue passenger service. In 1966 SEPTA had contracts with the PRR and RDG to continue commuter rail services in the Philadelphia region.[9]

The Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Company

The PRR and RDG operated both passenger and freight trains along their tracks in the Philadelphia region. Starting in 1915, both companies electrified their busiest lines to improve the efficiency of their passenger service. They used an overhead catenary trolley wire energized at 11,000 volts single-phase alternating current at 25 Hertz (Hz).[10] The PRR electrified the Paoli line in 1915, the Chestnut Hill West line in 1918, and the Media/West Chester and Wilmington lines in 1928. Both railroads continued electrifying lines into the 1930s, replacing trains pulled by steam locomotives with electric multiple unit cars and locomotives. PRR electrification reached Trenton and Norristown in 1930. RDG began electrified operation in 1931 to West Trenton, Hatboro (extended to Warminster in 1974) and Doylestown; and in 1933 to Chestnut Hill East and Norristown. The notable exception was the line to Newtown, the RDG's only suburban route not electrified. While the PRR expanded electrification throughout the northeast (ultimately stretching from Washington, D.C. to New York City), the RDG never expanded electric lines beyond the Philadelphia commuter district.[11]

By the late 1950s, commuter service had become a drag on profitability for the PRR and RDG, like most railroads of the era. Commuter service requires large amounts of equipment, large numbers of employees to operate equipment and station sites, and large amounts of maintenance on track that see extremely heavy usage for only six hours a day, five days a week.[9] Meanwhile, the rise in automobile ownership and the building of the Interstate Highway System chipped away at the steady patronage as population in the suburbs grew. When the Philadelphia suburbs were small towns, people lived close enough to a train station to walk to and from the trains. When the suburbs expanded into what had been fields and pastures, the trip to the station required an automobile, leading commuters to remain in their cars and drive all the way into the city as a matter of convenience.[9]

Both railroads shed a few minor money-losing routes, but more major pruning efforts ran into public opposition and government regulation.[11] Ending a major line involved hearings before the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), the predecessor to the Surface Transportation Board, which moved at a glacial pace and was capricious in the matter of approval, requiring one railroad to continue operating a local train on a route covered by four other trains while allowing another to discontinue a well-patronized train that had no competing lines.[9] In response, the railroads made commuting unpleasant for passengers by neglecting the upkeep of equipment.[9]

Faced with the possible loss of commuter service, local business interests, politicians, and the railroad unions in Philadelphia pushed for limited government subsidization.[11] In 1958, the city enacted the Philadelphia Passenger Service Improvement Corporation (PSIC), which consisted of a partnership with the RDG and PRR to subsidize service on both Chestnut Hill branches.[11] This was not enough to reverse the deterioration of the railroad infrastructure. By 1960, the PSIC assisted with services reaching as far as the city border in all directions. PSIC subsidized trains to Manayunk on the PRR's Schuylkill Branch[11] to Shawmont on the RDG Norristown line, to Fox Chase on the RDG Newtown line, and as far as Torresdale on the PRR's northeast corridor to New York City.[11] Subsequently, the city purchased new trains. The success of the PSIC subsidy program resulted in its expanding throughout the five-county suburban area under the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Compact (SEPACT) in 1962.[11] In 1966, SEPTA began contracts with the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Company to subsidize their commuter lines.

Still, the subsidies could not save the big railroads. The PRR attempted to stay solvent by merging with the New York Central Railroad on February 1, 1968, but the resulting company, Penn Central, went bankrupt on June 21, 1970. The RDG filed for bankruptcy in 1971.[9] Between 1974 and 1976, SEPTA ordered and accepted the delivery of the Silverliner IVs.

Conrail

In 1976, Conrail took over the railroad-related assets and operations of the bankrupt PRR and RDG railroads, including the commuter rail operations. Conrail provided commuter rail services under contract to SEPTA until January 1, 1983, when SEPTA assumed operations.[9]

The end of diesel routes

The Regional Rail SEPTA inherited from Conrail and its predecessor railroads was almost entirely run with electric-powered multiple unit cars and locomotives. However, Conrail (the Reading before 1976) operated four SEPTA-branded routes under contract throughout the 1970s, all of which originated from Reading Terminal. The Allentown via Bethlehem, Quakertown, and Lansdale service was gradually cut back. Alentown-Bethlehem service ended in 1979,[11] Bethlehem-Quakertown service ended July 1, 1981, and Quakertown-Lansdale service ended July 27, 1981. Service to Pottsville via Reading and Norristown, also ended July 27, 1981. West Trenton service previously ran to Newark Penn Station, but this was cut back to West Trenton on July 1, 1981, and replacement New Jersey Transit connecting service continued until 1983. The final service, Fox Chase-Newtown service, initially ended on July 1, 1981. It was re-established on October 5, 1981 as the Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line, which then ended on January 14, 1983.[11]

Most train equipment was either Budd Rail Diesel Cars, or locomotive-hauled push-pull trains with former RDG FP7s. The diesel equipment was maintained at the Reading Company/Conrail owned Reading Shops, in Reading, PA.

The services were phased out due to a number of reasons that included lack of ridership, a lack of funding outside the five-country area, withdrawal of Conrail as a contract carrier, a small pool of aging equipment that needed replacement, and a lack of SEPTA-owned diesel maintenance infrastructure. The death knell for any resumption of diesel service was the Center City commuter tunnel project, which lacks the necessary ventilation for exhaust-producing locomotives.[12]

Service from Cynwyd was extended to a new high-level station at Ivy Ridge in 1980, and the 52nd Street Station closed in the same year.

SEPTA takeover and strike

The transition from Conrail to SEPTA, overseen by General Manager David L. Gunn (who later became President of the New York City Transit Authority and Amtrak), was a turbulent one.[9] SEPTA attempted to impose lower transit (bus and subway driver's) pay scales and work rules, which was met by resistance by the BLE (an experiment was already in place on the diesel-only Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line, which used City Transit Division employees instead of traditional railroad employees as a bargaining chip). As the January 1, 1983 deadline approached, the unions stated they agreed to work even if new union contracts were not in place by the new year.[11] SEPTA had spent most of December 1982 preparing riders for the likelihood of no train service come the new year.[11] Even with the unions' offers to continue working, SEPTA insisted that a brief shutdown of service would still be necessary, arguing that it would not know until the eleventh hour how many Conrail employees would actually come to work for SEPTA.[11] In addition, SEPTA claimed that these employees would have to be qualified to work on portions of the system unfamiliar to them.[11]

A lawyer who regularly commuted from Newtown on the Fox Chase Rapid Transit line filed a class action lawsuit against SEPTA to force the agency to keep trains running.[11] The judge who heard the case, while agreeing that SEPTA probably would not be able initially to operate a full schedule, ordered the agency to keep as much train service running as possible.[11] This resulted in limited service after January 1, 1983 on all the RDG lines and the heavily patronized PRR Paoli line.[11] Full service was gradually restored over the next several weeks.[11]

The unions then surprised SEPTA on March 15, 1983 by going on strike, still without contracts, in an action timed to coincide with an expected City Transit Division strike.[11] At the time, the City Transit Division was chafing at SEPTA for discontinuing diesel service on the Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line on January 14, 1983, as personnel were paid higher salaries for traveling a considerable distance to operate trains based in Newtown.[11] SEPTA, however, settled with the transit union shortly before its strike deadline, a move that rail unions took as a betrayal.[11] The rail unions had hoped that with both the railroads and City Transit shut down, the unions could extract whatever settlement they desired.[9] The railroad strike lasted 108 days, and service did not resume until July 3, 1983, when the last holdout union agreed to a contract to settle from the other rail unions.[11]

In the end, SEPTA would treat the unions as proper railroad workers vs. transit operators, but their pay scale remains lower than that of other Northeast commuter railroads, such as NJ Transit and the Long Island Rail Road. The strike resulted in lower ridership, which took over 10 years to rebuild.

Expansion and cuts in the 1980s

Crises

The 1980s and 1990s were not kind to SEPTA. While the agency has spent most of its 50-year history staggering from crisis to crisis, the 1980s were a particularly low point. The era was defined by crippling strikes, engineer shortages, drastic service cuts and an abundance of mismanagement. State and local officials, commuters, and general observers were quick to brand SEPTA as the most inept of all the major transit agencies, though getting a handle on exactly was the cause of its ills was historically difficult.[13]

Railpace Newsmagazine contributor Gerry Williams commented that understanding what routinely transpires in SEPTA upper management rarely made itself clearly known to the general public. Frequently, there were various hidden agendas working in the background, often working at cross purposes with one another. This was often the result of the City (Philadelphia)/Suburban (Bucks, Delaware, Chester, Montgomery) split. The city government has historically been Democratic, the four suburban counties Republican. This factor is regularly influenced by the changing political winds at the state capital in Harrisburg.[13]

In addition, unlike all other U.S. railroad commuter agencies which are a state agency operated as a leg of its corresponding Department of Transportation, SEPTA is not a state agency and is beholden primarily to the five local governments which comprise it. Williams questioned why there has never been any massive public push to force SEPTA to "clean up its act." He concluded that the crisis within SEPTA "merely reflects the broader problems of local provincialism and petty political squabbles which are so rampant within the region."[13] Williams later commented that "unfortunately, there does not seem to be any group out there influential enough to bring shame on SEPTA, and SEPTA just may be beyond shaming anyway."[13] On November 16, 1984, the Columbia Avenue (now Cecil B. Moore Avenue) bridge near old Temple University Station was found to be unsafe, putting all four tracks out of service north of Market East Station. In December 1984, a temporary bridge opened, allowing service to resume north of Market East Station.[14]

Expansion

Service to Reading Terminal ended on November 6, 1984 in anticipation of the opening of the Center City Commuter Connection, which opened on November 12, 1984.[14] The tunnel, first proposed in the 1950s, is an underground connection between PRR and RDG lines; previously, PRR commuter trains terminated at Suburban Station and RDG at Reading Terminal. The connection converted Suburban Station into a through-station and rerouted RDG trains down a steep incline and into a tunnel that turns sharply west near the new Market East Station (now Jefferson Station). The conversion was meant to increase efficiency and reduce the number of tracks needed.[9] On April 28, 1985, the Airport Line opened, providing service from Suburban Station via 30th Street Station to Philadelphia International Airport.[14] This line runs along Amtrak's NEC, then crosses over onto Reading tracks that pass close to the airport. At the airport, a new bridge carries it over Interstate 95 and into the airport terminals between the baggage claim in arrivals and the check-in counters in departures.[9] In 1990, R5 service was extended from Downingtown to Coatesville and Parkesburg. However, on November 10, 1996, R5 service to Parkesburg was truncated to Downingtown. In 2006, SEPTA started negotiations with Wawa Food Markets to purchase land in Wawa, Pennsylvania to build a new Park-and-Ride facility for a planned restoration of service between Elwyn and Wawa on the Media/Elwyn Line, which previously ran to West Chester.

Shrinking service

Between 1979 and 1983, diesel locomotives were phased out. With insufficient operating funds and a desire to avoid maintaining deteriorating lines, SEPTA cut various services throughout the 1980s.[15] R3 West Chester service was truncated to Elwyn on September 19, 1986, due to unsatisfactory track beyond. R6 Ivy Ridge service was truncated to Cynwyd on May 17, 1986, due to concerns about the Manayunk Bridge over the Schuylkill River.[16] Service to Cynwyd ended altogether in 1988, but fierce political pressure brought resumed service. R8 diesel service between Fox Chase and Newtown ended on January 14, 1983, after SEPTA decided not to repair failing diesel train equipment.[17] The service was initially terminated on July 1, 1981 (along with diesel services to Allentown and Pottsville) and reinstated on October 5, 1981, using operators from the city transit division. This experimental Fox Chase Rapid Transit Line caused a rift in unions within the organization, adding to the March 1983 strike that lasted 108 days.[18]

On January 14, 1983, diesel service from Fox Chase-Newtown was discontinued due to failing train equipment, and service replaced with buses.[11]

SEPTA management was criticized for the cuts. Vukan Vuchic, the transit expert and University of Pennsylvania professor who designed the former R-numbering system for SEPTA, said he had never seen a city the size of Philadelphia "cut transit services quite as drastically as SEPTA. For a system that is already obsolete, any more cutbacks would be disastrous—and likely spell doom for transit in the Philadelphia region. This city would be the first in the world to do that."[19]

DVARP said that SEPTA purposely truncated service and that while other commuter railroad counterparts "in North America expand their rail services, SEPTA is the only one continuing to cut and cut and cut. The only difference between SEPTA and its railroad and transit predecessors is that SEPTA eliminates services to avoid rebuilding assets, while its predecessors (PRR, RDG and Conrail) kept service running while deferring maintenance."[15]

RailWorks

As a result of decades of deferred maintenance on the Reading Viaduct between the Center City Commuter Connection and Wayne Junction, SEPTA undertook a 10-month, $354 million (equivalent to $768.6 million in 2025) project to overhaul the viaduct in 1992 and 1993.[11] Labeled "RailWorks" by SEPTA, the project, spurred by an emergency bridge repair project in 1984-5 shortly after the tunnel opened, resulted in the replacement of several dilapidated bridges, the installing of new continuous welded rail and overhead catenary, the construction of new rail stations at Temple University and North Broad Street, and the upgrading of signals.[11]

Built by the Reading Company in 1911 to replace street-level running north of Reading Terminal, the Reading Viaduct is a series of bridges and embankments that allows trains to run on elevated railroad tracks, separated from road traffic and pedestrians. The 1911 bridge over Columbia (now Cecil B. Moore) Avenue near Temple University was in such poor condition that the bridge inspector actually saw the structure sag every time a train passed over the bridge; further inspection revealed that the bridge was in imminent danger of collapsing.[11] The viaduct was completely shut down during each phase, with the R6 Norristown, R7 Chestnut Hill East, and R8 Fox Chase lines suspended during the shutdown.[11] Other Reading lines only came as far into the city as the Fern Rock Transportation Center, where riders had to transfer to the Broad Street Subway.[11] The number of subway trains needed to carry both regular Broad Street Subway riders, as well as passengers transferring to the subway because of RailWorks, exceeded the capacity of the above-ground two-track stub-end Fern Rock Station of the Broad Street line.[11] In 1993, a loop track was added around the Fern Rock Yard which northbound trains use to approach the station from the rear.[11] The loop avoids a switch which had caused the bottleneck.

During RailWorks, SEPTA ran several diesel trains during peak-hours from the Reading side branches, along non-electrified Conrail trackage, to 30th Street Station.[11] Upon the completion of RailWorks, the Reading Viaduct became the "newest" piece of railroad owned by SEPTA, although other projects have since allowed improved service on the ex-Reading side of the system.[11]

Original route numbering plan

From 1984 to 2010, the regional rail lines were numbered from R1 to R8, with the notable omission of R4. The reasons for this were rather complicated, going back to the original planning stages.

Part of the planning for the Center City Commuter Connection was to decide on how trains would be routed through the tunnel and which branches would be paired up.[11] The original plan for the system was made by University of Pennsylvania professor Vukan Vuchic, based on the S-Bahn commuter rail systems in Germany.[11] Numbers were assigned to the PRR-side lines in order from south (Airport) to northeast (Trenton), and the RDG-side matches were chosen to roughly balance ridership, to attempt to avoid trains running full on one side and then running mostly empty on the other. The following lines were recommended:[20]

- R1 Airport to West Trenton

- R2 Marcus Hook to Warminster

- R3 Media/West Chester to Chestnut Hill West

- R4 Bryn Mawr (on the same tracks as the R5 Paoli) to Fox Chase

- R5 Paoli to Lansdale/Doylestown – express from Center City to Bryn Mawr, with R4 running local

- R6 Ivy Ridge to Norristown

- R7 Trenton to Chestnut Hill East

In addition to the Center City Commuter Connection, it was assumed that SEPTA would build one more connection, the Swampoodle Connection. This would allow PRR-side trains from Chestnut Hill West to join the RDG Norristown line instead of the PRR mainline at North Philadelphia station. The Chestnut Hill West line and the Norristown line run adjacent to each other at that point, in the Philadelphia neighborhood of Swampoodle. The Swampoodle Connection was never built, leading (among other factors) to the following changes:

- R3 could not go to Chestnut Hill West, so R3 trains from Media/West Chester instead went to West Trenton along the R1. Service to Chestnut Hill West was picked up by the R8.

- R4 was dropped; The R5 Paoli runs local along its entire length most of the time, and Fox Chase became half of the R8.

- R8 was added for Fox Chase to Chestnut Hill West service, using the former R4-Fox Chase and R3-Chestnut Hill West halves.

One of the assumptions in this plan was that ridership would increase after the connection was open. Instead, ridership dropped after the 1983 strike. While recent rises in oil prices have resulted in increased rail ridership for daily commuters, many off-peak trains run with few riders. Pairing up the rail lines based on ridership is less relevant today than it was when the system was implemented.

At a later time, R1 was applied to the former RDG side, shared with the R2 and R5 lines to Glenside, and R3 to Jenkintown, and R1-Airport trains ran to Glenside rather than becoming R3 trains to West Trenton. In later years, SEPTA became more flexible in order to cope with differences in ridership on various lines. After the original service patterns were introduced, the following termini changed:

- R2 – Marcus Hook was extended to Wilmington and Newark

- R3 – West Chester was cut back to Elwyn

- R5 – Paoli was extended to Downingtown and Parkesburg, then later cut back to Downingtown, and later re-extended to Thorndale

- R6 – Ivy Ridge was cut back to Cynwyd

On July 25, 2010, the R-numbering system was dropped and each branch was named after its primary termini.[21]

Ridership

| Railroad Division Annual Ridership, fiscal years 1979–2008 | |

|---|---|

| Fiscal year | Ridership[22] |

| 1979 | 31,539,688 |

| 1980 | 32,194,460 |

| 1981 | 27,109,824 |

| 1982 | 21,826,854 |

| 1983 | 12,856,207 |

| 1984 | 15,960,307 |

| 1985 | 18,788,437 |

| 1986 | 22,522,596 |

| 1987 | 22,932,834 |

| 1988 | 23,797,289 |

| 1989 | 24,143,591 |

| 1990 | 24,381,416 |

| 1991 | 23,312,199 |

| 1992 | 21,128,888 |

| 1993 | 19,185,111 |

| 1994 | 20,875,493 |

| 1995 | 22,558,492 |

| 1996 | 22,545,896 |

| 1997 | 23,012,000 |

| 1998 | 24,805,000 |

| 1999 | 25,088,000 |

| 2000 | 29,437,000 |

| 2001 | 28,671,000 |

| 2002 | 28,300,000 |

| 2003 | 28,058,200 |

| 2004 | 28,234,986 |

| 2005 | 28,632,658 |

| 2006 | 30,433,000 |

| 2007 | 31,712,000 |

| 2008 | 35,454,000[23] |

| 2009 | 35,443,000[24][25] |

| 2010 | 34,913,000[24][26] |

| 2011 | 35,387,000[24][27] |

| 2012 | 35,255,000[24][28] |

| 2013 | 36,023,000[29][30] |

When Conrail handled operations on SEPTA's behalf, overall ridership peaked in 1980 with over 373 million unlinked trips per year. The Regional Rail Division carried over 32 million passengers in 1980, a level which was not to be exceeded again for decades. Regional Rail ridership subsequently declined in 1982 after SEPTA ceased operating diesel service. It then sharply declined by half after SEPTA assumed operations in 1983, hitting a new low of just under 13 million passengers. This decline of ridership was the result of a drawn-out strike by the railroad unions, the discontinuing of service to over 60 stations, the increase in fares during a period of decreasing gasoline prices, and the unfamiliarity of SEPTA's management in operating a commuter railroad.

In 1992, ridership dipped again due to economic factors and due to SEPTA's RailWorks project, which shut down half of the railroad over two periods of several months each in 1992 and 1993. A mild recession in 1992–1994 also dampened ridership, but a booming economy in the late 1990s helped increase ridership to near the peak level of 1980.

In 2000, ridership started a slight decline due to the slow economy, but in 2003 ridership started increasing again. The average weekday passenger counts have not increased at the same rate as the total annual passenger counts, which may mean that weekend ridership is increasing. In 2008, Regional Rail ridership hit an all-time high of over 35 million. In 2009, it was down 1% of this high, but by fiscal year 2013 ridership reached a new high of over 36 million.[31]

2014 strike

On June 14, 2014, a strike shut down SEPTA's Regional Rail service after negotiations failed between SEPTA and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers. A total of 400 workers walked off the job.[32][33] As a result of the strike, SEPTA planned to add additional capacity on bus, subway, and trolley routes along with the Norristown High Speed Line during off-peak hours.[33] On the first day of the strike, Governor Tom Corbett asked President Barack Obama to appoint a presidential emergency board to attempt to end the labor dispute and force employees back to work.[33] A short time after 7 p.m. on June 14, President Obama signed an executive order forcing workers to return and continue negotiations through the presidential emergency board. SEPTA Regional Rail service resumed on June 15.[34]

Criticisms

"SEPTA has several techniques for sandbagging unwanted projects — raise concerns over safety, estimate costs unrealistically high, or push for rail trail conversions to stave off repeated calls for service restoration."

Transit mindset

SEPTA made it clear they were, at best, a reluctant railroad operator following the withdrawal of Conrail from regional rail operations in 1983. The regional rail network is viewed as a stepchild within the SEPTA organization, which explained the lengthy delays associated with the opening the Center City tunnel and Airport line.[13] SEPTA never wanted to get directly involved in railroad operations, with upper management historically viewing the regional rail division as a competitor rather than an ally of city-based operations (subway, trolley, etc.). SEPTA management also continues to willfully have little understanding of traditional railroad operations or ridership trends.[36]

In 1998, DVARP commented that SEPTA tends to view its commuter rail operations in transit terms rather than something different. Indeed, stations on SEPTA's regional rail lines tend to be closer together than stations on systems belonging to SEPTA's counterparts such as Metra, New Jersey Transit, MARC Train, Virginia Railway Express and Metro-North Railroad. Coupled with short route mileage of most lines, no onboard bathrooms, and the lack of diesel trains serving stations outside of SEPTA's electrified territory gives the railroad division more of an interurban feel and look than a traditional commuter operation.[36]

The operation of the defunct Fox Chase-Newtown segment of the Fox Chase Line as a transit operation from 1981 to 1983 — utilizing City Transit personnel instead of members of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen (BLET) — was the most notable example of "transitizing" (i.e. lower pay scale, frequent headways) a traditional railroad line.[37]

In the late 1990s, SEPTA resisted the commuter rail model used throughout North America when designing the Schuylkill Valley Metro project, initially preferring a light rail alternative for the 62-mile (100 km) line and then shifting to an unprecedented "Metrorail" model when fatal flaws were found in the light rail plan. DVARP called SEPTA's notion of bypassing traditional commuter rail "radical."[38] SEPTA's bias against conventional commuter rail on shared track — long the standard operating scenario for all other commuter railroads in North America — forced project costs over $2 billion and led to the rejection by the Federal Transit Administration as being too costly.[39]

Prior to the 1983 takeover of commuter operations, SEPTA considered running the former RDG side of the system from traditional railroad operations to transit-type operations, but dismissed it as unfeasible for the short term.[36] If converted to a transit-like operation, the regional rail system would operate outside of the U.S. railroad network, freeing it from most railroad-oriented federal regulations, including railroad work rules, federal safety equipment inspection requirements, and Railroad Retirement.[36]

Rail trails

Beginning in 2005, SEPTA began an aggressive campaign to rid themselves of maintaining derelict railroad lines under their ownership by leasing them to local townships or counties for use as interim recreational trails. SEPTA still retains the right to convert the leased trail back to active railroads should the need arise.[40] Rail proponents, such as the Pennsylvania Transit Expansion Coalition (PA-TEC) commented in 2010 that the trails were hastily constructed — such as the Pennypack Trail Extension (gravel vs. pavement, single access points) — in order to erase any presence of a railway.[40]

All of the track in the Abington Township section fo the former Fox Chase-Newtown line was removed for the Pennypack Trail Extension in July 2008. In October 2008, all of the track between Coopersburg and Hellertown section of former Quakertown-Bethlehem line is removed for Saucon Valley Rail Trail. In June 2009, all all track between Cynwyd and Pencoyd Viaduct section of former Cynwyd-Ivy Ridge line was removed for Cynwyd Heritage Trail.[41] In June 2010, all track between Pencoyd Viaduct and Ivy Ridge Station along former Cynwyd-Ivy Ridge line was removed for Ivy Ridge Trail.[42] Between July and September 2014, all track in the Lower Moreland Township section of the former Fox Chase-Newtown line was removed for Pennypack Trail Extension.

As of 2014, the following former routes are acting as interim rail trails:

| Rail line | Trackage type | Former stations affected | Township | Dismantled | Electrified/Diesel | Trail name | Length | Service suspension date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fox Chase/Newtown | single | Walnut Hill, Huntingdon Valley (planned), Bryn Athyn (planned), Woodmont (planned) | Abington Township, Lower Moreland Township (planned) | June 2008/Summer 2014 (planned) | Diesel | Pennypack Trail Extension | 6.37 mi (10.3 km) | All remaining trackage within Montgomery County was removed during Summer 2014[43][44] | |

| Cynwyd | double | Barmouth, Manayunk East, Ivy Ridge | Lower Merion Township | June 2009 – June 2010 | Electric | Cynwyd Heritage Trail[41] Ivy Ridge Trail[42] |

3.5 mi (5.6 km) | October 25, 1986 | |

| Bethlehem/Quakertown | double | Coopersburg, Center Valley, Hellertown, Bethlehem | Lower Saucon, Upper Saucon |

October 2008 | Diesel | Saucon Rail Trail[45][46] | 8.9 mi (14.3 km) | July 1, 1981 | |

| Chester Creek | single | Lenni, Knowlton, Chester Transportation Center | Middletown Township | TBD | Diesel | Chester Creek Rail Trail[47][48] | 9.5 mi (15.3 km) | June 1972 | SEPTA did not operate passenger trains on this line. Trains were last operated by the Penn Central in June 1972. Ownership on the line transferred to SEPTA in 1978 for railbanking purposes |

As traffic congestion in the Delaware Valley grew throughout the 1990s, resuming passenger service on SEPTA's unused lines was seen as a tool to battle the trend.[11] No other transit agency in North America has converted their unused rail lines into trails in the capacity that SEPTA has.[49] Public transit advocates—most notably PA-TEC—voiced their opposition in 2011 to the removal of the tracks as there are no notable instances in the U.S. of a rail trail converting back to rails.[40][49]

Suggestions by PA-TEC to convert the lines into rails with trails were seen by SEPTA officials as a safety hazard,[49] despite no documented safety issues by the U.S. Department of Transportation or Federal Railroad Administration.[50] The Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia also agreed that while trails serve a good purpose, "there is sufficient right-of-way available to support both future rail service and maintain trail usage. If there is insufficient right-of-way within the corridor to do both, then a relocation or rerouting of the trail to preserve the non-motorized route is necessary."[51]

John Pawson, author of Delaware Valley Rails: The Railroads and Rail Transit Lines of the Philadelphia Area questioned in 2010 why SEPTA is heavily involved with rail trails instead of public transit. Pawson, who was head of the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission Regional Citizens Committee until February 2011, stated that the creation of the Pennypack Trail on the Fox Chase/Newtown line is a "relatively cheap and quick process" but that "cheapness is its only advantage."[52] Pawson added that "the trail as built essentially runs from nowhere to nowhere. A relatively high-grade piece of infrastructure has been diverted (temporarirly, one would hope) to a relatively low-grade purpose. It's like taking over an expressway to use for someone's driveway."[52] Pawson concluded by saying "there is no need to pull up any more track. This real creek-side Pennypack Trail through Montgomery County and the restoration of the rail line in that county and beyond could be considered as a single valid political issue. Various groups including rail and trail proponents and others should work together for a joint project."[52]

See also

- Commuter rail in North America

- List of Pennsylvania railroads

- List of suburban and commuter rail systems

- List of North American commuter rail operators

- List of United States commuter rail systems by ridership

References

- ^ Revenue & Ridership Performance, February FY2016

- ^ 2008 SEPTA Railroad Division employee timetable accessed August 16, 2011

- ^ "SEPTA to Change Regional Rail designations". PlanPhilly. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ septa.org/reports

- ^ a b "SEPTA's new railcar model makes inaugural trip". The Philadelphia Inquirer. 30 October 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "SEPTA unveils first Silverliner V train". Progressive Railroading. 3 November 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c Philadelphia Transit Vehicles: Regional Rail roster

- ^ Nussbaum, Paul (May 27, 2015). "SEPTA plans to spend $154 million on new locomotives". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Drury, George H. (1992). The Train-Watcher's Guide to North American Railroads: A Contemporary Reference to the Major railroads of the U.S., Canada and Mexico. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing. pp. 19, 150, 201–202, 267. ISBN 0-89024-131-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ This is uncommon today; the vast majority of American households use double-phase, 60 Hz alternating current.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Williams, Gerry (1998). Trains, Trolleys and Transit: A Guide to Philadelphia Area Rail Transit. Piscataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company, Inc. pp. 13–16, 46–47, 95–98. ISBN 0-9621541-7-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ phillytrolley.org

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Gerry (September 1984). "SEPTA Scene". Railpace Newsmagazine. 4 (9). Picataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company, Inc.: 16–18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c pennways.com[unreliable source]

- ^ a b Mitchell, Matthew (April 1992). "SEPTA Budget for Fiscal 1993: Continued Rail Retrenchment". The Delaware Valley Association of Railroad Passengers.

- ^ "The Delaware Valley Rail Passenger". dvarp.org. Delaware Valley Association of Railroad Passengers. June 8, 1992. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ^ "Abandoned Rails: The Newtown Branch". www.abandonedrails.com. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ^ Newtown Branch history

- ^ Hyland, Tim (2004-12-09). "SEPTA in need of new ideas, more funding". Penn Current. Retrieved 2010-10-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ pennways.com/[unreliable source]

- ^ Lustig, David (November 2010). "SEPTA makeover". Trains Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing: 26.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ SEPTA 1997 Ridership Census, Annual Service Plans FY 2001 through 2007

- ^ FY 2008 SEPTA annual report

- ^ a b c d PEW Charitable Trusts Philadelphia 2013: The State of the City

- ^ "FY 2009 SEPTA annual report" (PDF). SEPTA. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "FY 2010 SEPTA annual report" (PDF). SEPTA. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ "FY 2011 SEPTA annual report" (PDF). SEPTA. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ "FY 2012 SEPTA annual report" (PDF). SEPTA. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Sarah Glover, "SEPTA Sets Regional Rail Ridership Record"

- ^ "FY 2013 SEPTA annual report" (PDF). SEPTA. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ SEPTA | SEPTA Sets New Record For Regional Rail Ridership

- ^ Mulvihill, Geoff (June 14, 2014). "SEPTA Commuter Rail Union on Strike". WCAU. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: NBC10.com. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Nussbaum, Paul (June 14, 2014). "Regional Rail strike begins; Corbett to seek federal help". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- ^ Dougherty, Mike, Jan Carabeo, and Andrew Kramer (June 14, 2014). "Obama Intervenes As SEPTA Regional Rail Strike Ends, Service Resumes Sunday". Philadelphia: KYW-TV. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams, Gerry (August 2008). "SEPTA Scene". Railpace Newsmagazine. 7 (8). Picataway, New Jersey: Railpace Company, Inc.: 49.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c d Williams, Gerry (August 1998). "SEPTA Scene". Railpace Newsmagazine.

- ^ Woodland, Dale W. (December 2003). "SEPTA's Diesels". Railpace Newsmagazine.

- ^ Wimp, Marilyn (1998-03-20). "Study: Ridership there for rail project: Nonprofit group labels the SEPTA proposal 'radical'" (PDF). Philadelphia Business Journal. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Rail link to Philadelphia won't occur, Rendell says". Reading Eagle. 2006-08-24.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c SEPTA Trail Signage letter

- ^ a b Cynwyd Heritage Trail

- ^ a b Ivy Ridge Green

- ^ Nussbaum, Paul (March 23, 2014). "Montco plans to convert more of rail line for recreation". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ http://www.septa.org/about/board/agenda-12-10-13.pdf SEPTA Board meeting minutes; December 10, 2013

- ^ "Ribbon Cut on Saucon Rail Trail"

- ^ Saucon Rail Trail update 2010

- ^ chestercreektrail.org

- ^ delcotimes.com

- ^ a b c PA-TEC discussion SEPTA's rail trails

- ^ "Rails-with-Trails: Lessons Learned, U.S. Department of Transportation"

- ^ Bicycle Coalition's Position on SEPTA rail trail initiative

- ^ a b c dvrpc.org

Further reading

- Pawson, John R. (1979). Delaware Valley Rails: The Railroads and Rail Transit Lines of the Philadelphia Area. Willow Grove, PA: Pawson. ISBN 0-9602-0800-3. OCLC 5446017.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)