Michael Craig-Martin

Sir Michael Craig-Martin | |

|---|---|

|

</ref> is a contemporary conceptual artist and painter. He is noted for fostering the Young British Artists, many of whom he taught, and for his conceptual artwork, An Oak Tree. He is Emeritus Professor of Fine Art at Goldsmiths.[1] His memoir and advice for the aspiring artist, On Being An Artist, was published by London-based publisher Art / Books in April 2015.[2][3]

Early life and career

The Dublin-born and reared Craig-Martin was given a religious education, for eight years in a Roman Catholic school which was run by nuns, and later at the English Benedictine Priory School (now St. Anselm's Abbey School), where pupils were encouraged to look at religious imagery in illuminated glass panels and stained-glass windows.[4] He gained an interest in art through one of the priests, who was an artist, and was also strongly impressed by a display in the Phillips Collection of work by Mark Rothko.[4]

Michael Craig-Martin studied in the Lycée Français in Bogotá, Colombia, where his father had employment for a while. Drawing classes in the Lycée by an artist, Antonio Roda, gave him a wider perspective on art.[4] His parents had no inclinations towards art, although they did have on display in their home Picasso's Greedy Child.[5][6] Back in Washington, he attended drawing classes given there by artists, then in 1959 attended Fordham University in New York for English Literature and History, while also starting to paint.[5]

In mid-1961 [7] Craig-Martin studied art at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, and in the autumn began a painting course at Yale University, where the teaching was strongly influenced by the multi-disciplinary experimentation and minimalist theories on colour and form of Josef Albers, a former head of department. Craig-Martin later said, "Everything I know about colour comes from that course". Tutors on the course included artists, Alex Katz and Al Held.[5]

Work

Craig-Martin has lived and worked in London since 1966.[8] From his early box-like constructions of the late 60’s he moved increasingly to the use of ordinary household objects. In the late 70’s he began to make line drawings of ordinary objects, creating over the years an ever-expanding vocabulary of images which form the foundation of his work to this day. During the 1990s the focus of his work shifted decisively to painting, with the same range of boldly outlined motifs and vivid color schemes applied both to works on canvas, and to increasingly complex installations of wall paintings.[9]

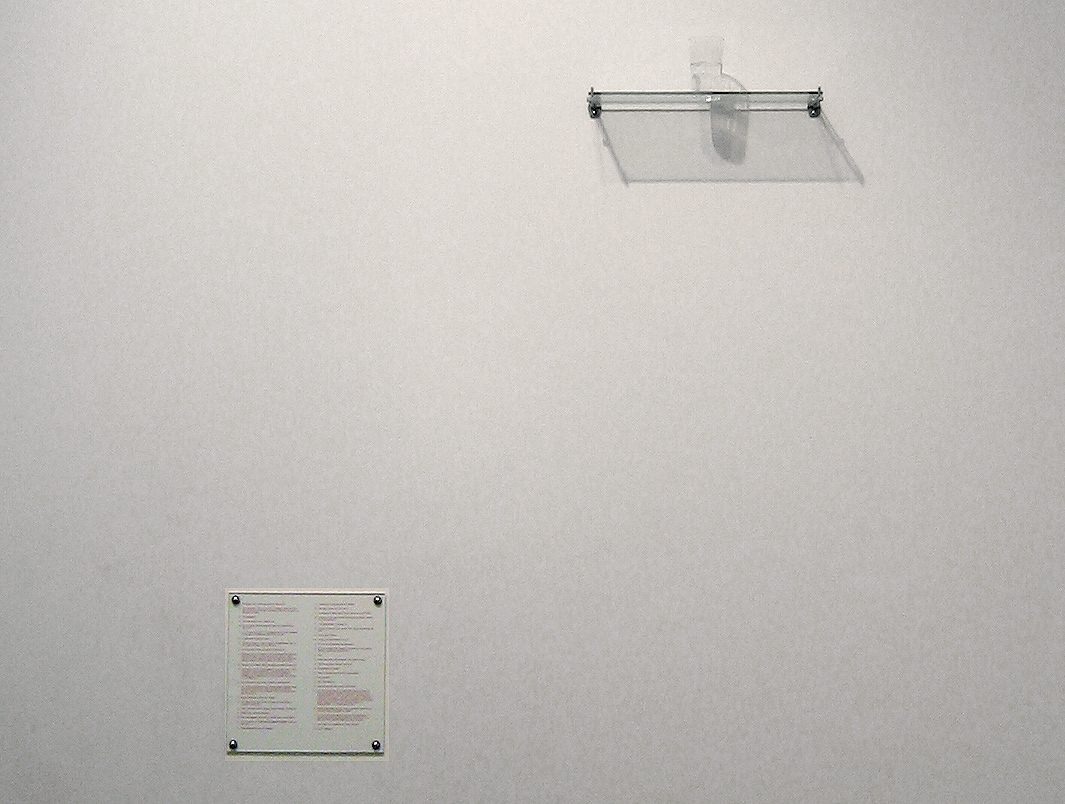

An Oak Tree

In 1973[10] he exhibited the seminal piece An Oak Tree. The work consists of a glass of water standing on a shelf attached to the gallery wall next to which is a text using a semiotic argument to explain why it is in fact an oak tree. Nevertheless, on one occasion when it was barred by Australian Customs officials from entering the country as vegetation, he was forced to explain it was really a glass of water.[11] The work was bought by the National Gallery of Australia in 1977; however, the Tate gallery has an artist's copy.[11]

Young British Artists

In the 1980s Craig-Martin was a tutor at Goldsmiths College, Department of Art, and was a significant influence on the emerging YBA generation, including Damien Hirst. He was also helpful in promoting the Freeze show to established art-world figures. In 1995 he curated Drawing the Line: a comprehensive touring exhibition on the history of line drawing for the Southbank Centre, London.[12] Craig-Martin and his influence were described in an article in the Observer regarding the mentors of British art, entitled Schools of Thought.[13] Craig-Martin has been a trustee of the Tate Gallery and is a trustee of the National Art Collections Fund.

Exhibitions

Craig-Martin had his first one-man exhibition at the Rowan Gallery in London in 1969. Since then he has shown regularly both in the UK and abroad, Specifically, he has presented major site-specific installations in museums and galleries around the world, and represented Britain at the São Paulo Art Biennial in 1998.[14] His solo museum exhibitions include “Always Now,” Kunstverein Hannover (1998); IVAM, Valencia (2000); “Living,” Sintra Museum of Modern Art, Portugal (2001); “Signs of Life,” Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (2006); and “Less Is Still More,” Museum Haus Esters, Krefeld, Germany (2013).[15] He made his American debut in the "Projects" series at the Museum of Modern Art.[16]

A retrospective of Craig-Martin's work took place at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1989. In 2006, the Irish Museum of Modern Art presented "Michael Craig-Martin: Works 1964–2006" which included works from over 40 years of Craig-Martin's career. The exhibition showed around 50 paintings, sculptures, wall drawings, neon works and text pieces by the artist, covering everything from his sculptures to digital works. One of his works called On the Table (1970) involved four metal buckets suspended on a table, exemplifying the influence of Minimalism and Conceptualism on Craig-Martin. An Oak Tree (1973), consisting of "an ordinary glass of water on an equally plain shelf, accompanied by a text in which Craig-Martin asserts the supremacy of the artist's intention over the object itself ... is now widely regarded as a turning point in the development of conceptual art".[17]

In 2015, Michael Craig-Martin's exhibition "Transience" at the Serpentine Galleries brought together works from 1981 to 2015, including representations of once familiar yet obsolete technology; laptops, games consoles, black-and-white televisions and incandescent lightbulbs that highlighted the increasing transience of technological innovation.[18]

Collections

Craig-Martin’s work is represented in public collections worldwide, including Museum of Modern Art, New York; Tate, London; Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. Permanent large-scale installations are on view at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, London and European Investment Bank, Luxembourg.[19]

Personal life

While at Yale University, Craig-Martin met Jan Hashey, whom he later married. The couple had a daughter, Jessica Craig-Martin, a photographer.[20] Craig-Martin and Hashey later divorced.[21]

Craig-Martin was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2001 Birthday Honours.[22]

Craig-Martin was knighted in the 2016 Birthday Honours for services to art.[23]

See also

References

- ^ Goldsmiths College staff list; retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-908970-18-3

- ^ Art / Books website

- ^ a b c Cork, Richard (2006). Michael Craig-Martin, p. 17, Thames & Hudson: London; ISBN 978-0-500-09332-0; ISBN 0-500-09332-6.

- ^ a b c Cork, Richard, p. 18.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Cork, Richard (2006). Michael Craig-Martin. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-09332-0.

- ^ Roberta Smith (15 March 1991), Wholesome Enough for Children New York Times.

- ^ Michael Craig-Martin Gagosian Gallery.

- ^ Manchester, Eliza. "An Oak Tree 1973: Short text", Tate, December 2002; retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ a b Sherwin, Brian. "Art Space Talk: Michael Craig-Martin", myartspace.com, 16 August 2007; retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ^ Collection: Michael Craig-Martin British Council.

- ^ Life: The Observer Magazine – A celebration of 500 years of British Art – 19 March 2000

- ^ Collection: Michael Craig-Martin British Council.

- ^ Michael Craig-Martin, June 12 - August 16, 2014 Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong.

- ^ Roberta Smith (15 March 1991), Wholesome Enough for Children New York Times.

- ^ Michael Craig-Martin at the Irish Museum of Modern Art, ARTINFO, 5 October 2006, retrieved 23 April 2008

- ^ Michael Craig-Martin: Transience at the Serpentine Galleries, London, 25 November 2015, retrieved 26 February 2016

- ^ Michael Craig-Martin, 12 June – 16 August 2014 Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong.

- ^ David Colman (29 June 2003), Possessed – Letting Fate Take the Picture New York Times.

- ^ Connolly, Cressida (24 November 2007), Michael Craig-Martin: Out of the Ordinary, London: telegraph.co.uk, retrieved 14 January 2010

- ^ "No. 56237". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 16 June 2001. - ^ "No. 61608". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 11 June 2016.

External links

- 1941 births

- Living people

- Royal Academicians

- Contemporary artists

- Academics of Goldsmiths, University of London

- Irish artists

- Irish contemporary artists

- Irish expatriates in the United Kingdom

- People from Dublin (city)

- Alumni of the Académie de la Grande Chaumière

- Yale University alumni

- Fordham University alumni

- Knights Bachelor