Latin America–United States relations

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Article needs restructuring and fixing of continuous grammar/spelling issues. (April 2016) |

Until the end of the nineteenth century, United States had special relationships primarily with nearby Mexico and Cuba. Otherwise, relationships with other Latin American countries was of minor importance to both sides, consisting mostly of a small amount of trade. Apart from Mexico, there was little migration to the United States, and little American financial investment. Politically and economically, Latin America (apart from Mexico and the Spanish colony of Cuba) was largely tied to Britain. The United States had no involvement in the process by which Spanish possessions broke away and became independent around 1820. In cooperation with and help from Britain, the United States issued the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, warning against the establishment of any additional European colonies in Latin America.

Texas, settled primarily by Americans, fought a successful war of independence against Mexico in 1836. Mexico refused to recognize the independence and warned that annexation to the United States meant war. Annexation came in 1845; war came in 1846. The American military was easily triumphant. The result was the American purchase of New Mexico, Arizona, California and adjacent areas. About 60,000 Mexicans remained in the new territories and became US citizens. France took advantage of the American Civil War (1861–65), using its army to take over Mexico regardless of strong American protests. With the US victorious in the war, France pulled out, leaving its puppet emperor to his fate in front of a Mexican firing squad.

As unrest in Cuba escalated in the 1890s the United States demanded reforms that Spain was unable to accomplish. The result was the short successful Spanish–American War of 1898, in which United States acquired Puerto Rico, and set up a protectorate over Cuba. The building of the Panama Canal absorbed American attention from 1903. The US facilitated a revolt that made Panama independent, and set up the Panama Canal Zone as an American owned and operated district that was finally returned to Panama in 1979. The Canal opened in 1914, and proved a major factor in world trade. United States paid special attention to protection of the military approaches to the Panama Canal, including threats by Germany. Repeatedly it seized temporary control of several countries, especially Haiti and Nicaragua.

The Mexican Civil War started in 1911; it alarmed American business interests that had invested in Mexican mines and railways. Tensions escalated almost to the point of war, but the crisis was peacefully resolved and the main grievances between the two nations over oil were resolved by the late 1930s. Large numbers of Mexicans fled the war-torn revolution into the southwestern United States. Meanwhile the United States increasingly replaced Britain as the major trade partner and financier throughout Latin America. The US adopted a “Good Neighbor Policy" in the 1930s, which meant friendly trade relations would continue regardless of political conditions or dictatorships. United States signed up the major countries as allies against Germany and Japan in World War II. Argentina, however, refused to cooperate; the diplomatic tensions died down after the war.

The turn of Castro's revolution in Cuba after 1959 toward Soviet communism alienated the United States. An attempted invasion failed, and at the peak of the Cold War in 1962, the Cuban Missile Crisis threatened major war as the Soviet Union installed nuclear weapons in Cuba to defend it from an American invasion. There was no invasion, but the United States imposed an economic boycott on Cuba that remains in effect, as well as a break of diplomatic relations that lasted until 2015. The US also saw the rise of left-wing governments in central America as a threat, and in some cases, overthrew democratically elected governments perceived at the time as becoming left-wing or unfriendly to U.S. interests.[1] Examples include the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état, the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état, the 1973 Chilean coup d'état and the support of the Contra rebels in Nicaragua. In the 1980s, the United States gave strong support to anti-Communist forces in Latin America. The fall of Soviet communism in 1989–91 largely ended the communist threat. By 2015 relations remain tense between United States and Venezuela. Large-scale Mexican immigration grew the late twentieth century, so that over 10 million undocumented immigrants lived in the United States, sending money back home and asking whether they or their children could get US citizenship. Furthermore large-scale immigration came from smaller countries such as Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

By the late nineteenth century the rapid economic growth of the United States increasingly troubled Latin America. A Pan-American Union was created under American auspices, but it had little impact. As did its successor the Organization of American states. After 1960, Latin America increasingly supplied illegal drugs, especially marijuana and cocaine to the rich American market. One consequence was the growth of extremely violent drug gangs in Mexico and other parts of Central America to control the drug supply. NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) took effect in 1994, and dramatically increased the volume of trade among Mexico United States and Canada.

19th century to World War I

Monroe Doctrine

The 1823 Monroe Doctrine, which began the United States' policy of isolationism, deemed it necessary for the United States to refrain from entering into European affairs but to protect Western hemisphere nations from foreign military intervention. In cooperation with and help from Britain, the United States issued the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, warning against the establishment of any additional European colonies in Latin America.

The Anderson–Gual Treaty

The Anderson–Gual Treaty (formally, the General Convention of Peace, Amity, Navigation, and Commerce) was an 1824 treaty between the United States and Gran Colombia integrated by modern day countries of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama and Ecuador . It is the first bilateral treaty that the United States concluded with another American country.

The treaty was concluded in Bogotá on 3 October 1824 and signed by U.S. diplomat Richard Clough Anderson and by minister Pedro Gual Escandón. It was ratified by both countries and entered into force in May 1825.

The commercial provisions of the treaty granted reciprocal most-favored-nation status was maintened despite the separation of the Gran Colombia in 1830. The treaty contained a clause that stated it would be in force for 12 years after ratification by both parties; the treaty therefore expired in 1837.

The Anfictionic Congress of Panama

The notion of an international union in the New World was first put forward by the venezuelan Liberator Simón Bolívar[3] who, at the 1826 Congress of Panama (still being part of Gran Colombia), proposed creating a league of all American republics, with a common military, a mutual defense pact, and a supranational parliamentary assembly. This meeting was attended by representatives of Gran Colombia, Peru, Bolivia,the United Provinces of Central America, and Mexico but the grandly titled "Treaty of Union, League, and Perpetual Confederation" was ultimately ratified only by Gran Colombia. Bolívar's dream soon floundered with civil war in Gran Colombia, the disintegration of Central America, and the emergence of national rather than New World outlooks in the newly independent American republics. Bolívar's dream of American unity was meant to unify Hispanic American nations against external powers. Despite their eventual departure, of the two United States delegates envoy by president John Quincy Adams, one (Richard Clough Anderson) died en route to Panama, and the other (John Sergeant) only arrived after the Congress had concluded its discussions. Thus Great Britain, which attended with only observer status, managed to acquire many good trade deals with Latin American countries.

Mexican - American war

Texas, settled primarily by Americans, fought a successful war of independence against Mexico in 1836. Mexico refused to recognize the independence and warned that annexation to the United States meant war. Annexation came in 1845; war came in 1846. The American military was easily triumphant. The result was the American purchase of New Mexico, Arizona, California and adjacent areas. About 60,000 Mexicans remained in the new territories and became US citizens. France took advantage of the American Civil War (1861–65), using its army to take over Mexico regardless of strong American protests. With the US victorious in the war, France pulled out, leaving its puppet emperor to his fate in front of a Mexican firing squad. The Monroe Doctrine maintained the autonomy of Latin American nations, thereby allowing the United States to impose its economic policies at will.

The Ostend Manifesto

The Ostend Manifesto of 1854 was a proposal Circulated by American diplomats that proposed the United States offer to purchase Cuba from Spain while implying that the U.S. should declare war if Spain refused. Nothing came of it. Diplomatically, the US was content to see the island remain in Spanish hands so long as it did not pass to a stronger power such as Britain or France.

Venezuelan crisis of 1895

* The extreme border claimed by Britain

* The current boundary (roughly) and

* The extreme border claimed by Venezuela

The Venezuelan crisis of 1895[a] occurred over Venezuela's longstanding dispute with the United Kingdom about the territory of Essequibo and Guayana Esequiba, which Britain claimed as part of British Guiana and Venezuela saw as Venezuelan territory. As the dispute became a crisis, the key issue became Britain's refusal to include in the proposed international arbitration the territory east of the "Schomburgk Line", which a surveyor had drawn half a century earlier as a boundary between Venezuela and the former Dutch territory of British Guiana.[4] By 17 December 1895, President Grover Cleveland delivered an address to the United States Congress reaffirming the Monroe Doctrine and its relevance to the dispute. The crisis ultimately saw Britain accept the United States' intervention to force arbitration of the entire disputed territory, and tacitly accept the United States' right to intervene under the Monroe Doctrine. A tribunal convened in Paris in 1898 to decide the matter, and in 1899 awarded the bulk of the disputed territory to British Guiana.[5]The Anglo-Venezuelan boundary dispute asserted for the first time a more outward-looking American foreign policy, particularly in the Americas, marking the United States as a world power. This was the earliest example of modern interventionism under the Monroe Doctrine in which the USA exercised its claimed prerogatives in the Americas.[6]

The Spanish–American War (1898)

The Spanish–American War was a conflict fought between Spain and the United States in 1898. Hostilities began in the aftermath of sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor leading to American intervention in the Cuban War of Independence. American acquisition of Spain's Pacific possessions led to its involvement in the Philippine Revolution and ultimately in the Philippine–American War.

Revolts against Spanish rule had been occurring for some years in Cuba as in the Virginius Affair in 1873. In the late 1890s, US public opinion was agitated by anti-Spanish propaganda led by journalists such as Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst which used yellow journalism to call for war. However, the Hearst and Pulitzer papers circulated among the working class in New York City and did not reach a national audience. [7][8]

After the mysterious sinking of the US Navy battleship Maine in Havana harbor, political pressures from the Democratic Party pushed the administration of Republican President William McKinley into a war he had wished to avoid.[9] Spain promised time and again it would reform but never delivered. The United States sent an ultimatum to Spain demanding it surrender control of Cuba. First Madrid, then Washington, formally declared war.[10]

Although the main issue was Cuban independence, the ten-week war was fought in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. US naval power proved decisive, allowing expeditionary forces to disembark in Cuba against a Spanish garrison already facing nationwide Cuban insurgent attacks and further wasted by yellow fever.[11] Numerically superior Cuban, Philippine, and US forces obtained the surrender of Santiago de Cuba and Manila despite the good performance of some Spanish infantry units and fierce fighting for positions such as San Juan Hill.[12] With two obsolete Spanish squadrons sunk in Santiago de Cuba and Manila Bay and a third, more modern fleet recalled home to protect the Spanish coasts, Madrid sued for peace.[13]

The result was the 1898 Treaty of Paris, negotiated on terms favorable to the US, which allowed it temporary control of Cuba, and ceded ownership of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine islands. The cession of the Philippines involved payment of $20 million ($732,480,000 today) to Spain by the US to cover infrastructure owned by Spain.[14]

The war began exactly fifty-two years after the beginning of the Mexican–American War. It was one of only five US wars (against a total of eleven sovereign states) to have been formally declared by Congress.[15]

US Secretary of State James G. Blaine created the Big Brother policy in the 1880s, aiming to rally Latin American nations behind US leadership and to open Latin American markets to U.S. traders. Blaine served as United States Secretary of State in 1881 in the cabinet of President James Garfield and again from 1889 to 1892 in the cabinet of President Benjamin Harrison. As part of the policy, Blaine arranged for and lead as the first president the First International Conference of American States in 1889. A few years later, the Spanish–American War in 1898 provoked the end of the Spanish Empire in the Caribbean and the Pacific, with the 1898 Treaty of Paris giving the US control over the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam, and control over the process of independence of Cuba, which was completed in 1902.

Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903

The Venezuelan crisis of 1902–03 was a naval blockade from December 1902 to February 1903 imposed against Venezuela by Britain, Germany and Italy over President Cipriano Castro's refusal to pay foreign debts and damages suffered by European citizens in the recent Venezuelan civil war. Castro assumed that the United States' Monroe Doctrine would see the US prevent European military intervention, but at the time the president Roosevelt saw the Doctrine as concerning European seizure of territory, rather than intervention per se. With prior promises that no such seizure would occur, the US allowed the action to go ahead without objection. The blockade saw Venezuela's small navy quickly disabled, but Castro refused to give in, and instead agreed in principle to submit some of the claims to international arbitration, which he had previously rejected. Germany initially objected to this, particularly as it felt some claims should be accepted by Venezuela without arbitration.

U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt forced the blockading nations to back down by sending his own larger fleet under Admiral George Dewey and threatening war if the Germans landed.[16] With Castro failing to back down, US pressure and increasingly negative British and American press reaction to the affair, the blockading nations agreed to a compromise, but maintained the blockade during negotiations in over the details. This led to the signing of the Washington Protocols agreement on 13 February 1903 which saw the blockade lifted, and Venezuela commit 30% of its customs duties to settling claims. When the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague subsequently awarded preferential treatment to the blockading powers against the claims of other nations, the US feared this would encourage future European intervention.

The Panama Canal

Theodore Roosevelt, who became President of the United States in 1901, believed that a U.S.-controlled canal across Central America was a vital strategic interest to the United States. This idea gained wide impetus following the destruction of the battleship USS Maine, in Cuba, on February 15, 1898.[citation needed] The USS Oregon, a battleship stationed in San Francisco, was dispatched to take her place, but the voyage—around Cape Horn—took 67 days. Although she was in time to join in the Battle of Santiago Bay, the voyage would have taken just three weeks via Panama.

Roosevelt was able to reverse a previous decision by the Walker Commission in favour of a Nicaragua Canal, and pushed through the acquisition of the French Panama Canal effort. Panama was then part of Colombia, so Roosevelt opened negotiations with the Colombians to obtain the necessary permission. In early 1903 the Hay–Herrán Treaty was signed by both nations, but the Colombian Senate failed to ratify the treaty.

In a controversial move, Roosevelt implied to Panamanian rebels that if they revolted, the U.S. Navy would assist their cause for independence. Panama proceeded to proclaim its independence on 3 November 1903, and the USS Nashville in local waters impeded any interference from Colombia (see gunboat diplomacy).

The victorious Panamanians returned the favor to Roosevelt by allowing the United States control of the Panama Canal Zone on 23 February 1904, for US$10.000.000 (as provided in the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, signed on 18 November 1903).

The Roosevelt Corollary and Venezuelan Economic Issues

When the Venezuelan government under Cipriano Castro was no longer able to placate the demands of European bankers in 1902, naval forces from Britain, Italy, and Germany erected a blockade along the Venezuelan coast and even fired upon coastal fortifications.

The U.S. president then formulated the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, in December 1904, which asserted the right of the United States to intervene in Latin American nations' affairs.[18] In its altered state, the Monroe Doctrine would now consider Latin America as an agency for expanding U.S. commercial interests in the region, along with its original stated purpose of keeping European hegemony from the hemisphere. In addition, the corollary proclaimed the explicit right of the United States to intervene in Latin American conflicts exercising an international police power.

During the presidency of Juan Vicente Gómez, petroleum was discovered under Lake Maracaibo in 1914. Gómez managed to deflate Venezuela's staggering debt by granting concessions to foreign oil companies, which won him the support of the United States and the European powers. The growth of the domestic oil industry strengthened the economic ties between the U.S. and Venezuela.

The Mexican Revolution, 1910-1920

The United States appears to have pursued an inconsistent policy toward Mexico during the Mexican Revolution, but in fact it was the pattern for U.S. diplomacy. "Every victorious faction between 1910 and 1919 enjoyed the sympathy, and in most cases the direct support of U.S. authorities in its struggle for power. In each case, the administration in Washington soon turned on its new friends with the same vehemence it had initially expressed in supporting them."[19] The U.S. turned against the regimes it helped install when they began pursuing policies counter to U.S. diplomatic and business interests.[20]

The U.S. sent troops to the border with Mexico when it became clear in March 1911 that the regime of Porfirio Díaz could not control revolutionary violence.[21] Díaz resigned, opening the way for free elections that brought Francisco I. Madero to the presidency in November 1911. The U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson conspired with opposition forces to topple Madero's regime in February 1913, during what is known as the Ten Tragic Days.

The U.S. intervened in Mexico twice under the Presidency of Woodrow Wilson, the United States occupation of Veracruz by the Navy in 1914 and mounted a punitive operation in northern Mexico in the Pancho Villa Expedition, aimed at capturing the northern revolutionary who had attacked Columbus, New Mexico.

Banana Wars

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the US carried on several military interventions in what became known as the Banana Wars. The term arose from the connections between the interventions and the preservation of US commercial interests, starting with the United Fruit corporation, which had significant financial stakes in production of bananas, tobacco, sugar cane, and various other agricultural products throughout the Caribbean, Central America and the northern portions of South America. US citizens advocating imperialism in the pre–World War I era often argued that these conflicts helped central and South Americans by aiding in stability. Some imperialists argued that these limited interventions did not serve US interests sufficiently and argued for expanded actions in the region. Anti-imperialists argued that these actions were a first step down a slippery slope towards US colonialism in the region.

Some modern observers have argued that if World War I had not lessened American enthusiasm for international activity these interventions might have led to the formation of an expanded U.S. colonial empire, with Central American states either annexed into Statehood like Hawaii or becoming American territories, like the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam. This view is, however, heavily disputed, especially as, after a decrease in activity during and after World War I, the U.S. government intervened again in the 1920s while again stating that no colonial ambitions were held. The Banana Wars ended with the 1933 Good Neighbor Policy of President Franklin D. Roosevelt; no official American colonies had been created.

The countries involved in the Banana Wars include:

- Cuba – Sometimes not counted among the banana wars, as the Platt Amendment granted the United States the right to militarily intervene on any occasion in which Cuba's independence was threatened

- US Occupation of the Dominican Republic

- Honduras

- Haiti (see United States occupation of Haiti)

- Nicaragua (see United States occupation of Nicaragua)

- Panama

Though many other countries in the region may have been influenced or dominated by American banana or other companies, there is no history of U.S. military intervention during this period in those countries.

1930s–1940s

The Good Neighbor policy was the foreign policy of the administration of United States President Franklin Roosevelt toward the countries of Latin America. The United States wished to have good relations with its neighbors, especially at a time when conflicts were beginning to rise once again, and this policy was more or less intended to garner Latin American support. Giving up unpopular military intervention, the United States shifted to other methods to maintain its influence in Latin America: Pan-Americanism, support for strong local leaders, the training of national guards, economic and cultural penetration, Export-Import Bank loans, financial supervision, and political subversion. The Good Neighbor Policy meant that the United States would keep its eye on Latin America in a more peaceful tone. On 4 March 1933, Roosevelt stated during his inaugural address that: "In the field of world policy I would dedicate this nation to the policy of the good neighbor—the neighbor who resolutely respects himself and, because he does so, respects the rights of others."[22] This position was affirmed by Cordell Hull, Roosevelt's Secretary of State at a conference of American states in Montevideo in December 1933. Hull said: "No country has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another" (LaFeber, 376). This is apparent when in December of the same year Roosevelt again gave verbal evidence of a shift in U.S. policy in the region when he stated: "The definite policy of the United States from now on is one opposed to armed intervention."[23]

Expulsion of Germans from Latin America to the U.S. during World War II

After the United States declared war on Germany, the Federal Bureau of Investigation drafted a list of Germans in fifteen Latin American countries it suspected of subversive activities and demanded their eviction to the U.S. for detention. In response, several countries expelled a total of 4,058 Germans to the U.S. Some 10% to 15% of them were Nazi party members, including some dozen recruiters for the Nazis' overseas arm and eight people suspected of espionage. Also among them were 81 Jewish Germans who had only recently fled persecution in Nazi Germany. The bulk were ordinary Germans, who were residents in these states for years or decades. Some were expelled because corrupt Latin American officials took the opportunity to seize their property, or ordinary Latin Americans were after the financial reward that U.S. intelligence paid informants. Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico did not participate in the U.S. expulsion program.[24]

1940s–1960s: the Cold War and the "hemispheric defense" doctrine

"Most Latin Americans have seen their neighbor to the north (the United States) growing richer; they have seen the elite elements in their own societies growing richer – but the man in the street or on the land in Latin America today still lives the hand-to-mouth existence of his great, great grandfather... They are less and less happy with situations in which, to cite one example, 40 percent of the land is owned by 1 percent of the people, and in which, typically, a very thin upper crust lives in grandeur while most others live in squalor."

— U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright, in a speech to Congress on United States policy in Latin America[25]

Officially started in 1947 with the Truman doctrine theorizing the "containment" policy, the Cold War had important consequences in Latin America, considered by the United States to be a full part of the Western Bloc, called "free world", in contrast with the Eastern Bloc, a division born with the end of World War II and the Yalta Conference held in February 1945. It "must be the policy of the United States", Truman declared, "to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or outside pressures." Truman rallied to spend $400.000.000 to intervene in the Greek civil war, while the CIA (created by the National Security Act of 1947) intervention in this country was its first act of birth. By aiding Greece, Truman set a precedent for U.S. aid to regimes, no matter how repressive and corrupt, that requested help to fight communists.[26] Washington began to sign a series of defense treaties with countries all over the world, including the North Atlantic Treaty of 1949 which created NATO, and the ANZUS in 1951 with Australia and New Zealand. Moscow response to NATO and to the Marshall Plan in Europe included the creation of the COMECON economic treaty and the Warsaw Pact defense alliance, gathering Eastern Europe countries which had fallen under its sphere of influence. After the Berlin Blockade by the Soviet Union, the Korean War (1950–53) was one of the first conflicts of the Cold War, while the US would succeeded France in the counter-revolutionary war against Viet-minh in Indochina.

In Latin America itself, the US defense treaty was the Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance (aka Rio Treaty or TIAR) of 1947, known as the "hemispheric defense" treaty. It was the formalization of the Act of Chapultepec, adopted at the Inter-American Conference on the Problems of War and Peace in 1945 in Mexico City. The US had maintained a hemispheric defense policy under the Monroe Doctrine, and during the 1930s had been alarmed by Axis overtures toward military cooperation with Latin American governments, in particular apparent strategic threats against the Panama Canal. During the war, Washington had been able to secure Allied support from all individual governments except Uruguay, which remained neutral, and wished to make those commitments permanent. With the exceptions of Trinidad and Tobago (1967), Belize (1981), and the Bahamas (1982), no countries that became independent after 1947 have joined the treaty. In April 1948, the Organization of American States was created, during the Ninth International Conference of American States held in Bogotá and led by U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall. Member states pledged to fight communism on the American continent. Twenty-one American countries signed the Charter of the Organization of American States on 30 April 1948.

Operation PBSUCCESS, which overthrew the democratically-elected President of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán in 1954, was to be one of the first in a long series of US interventions in Latin America during the Cold War. It immediately followed the overthrow of Mossadegh in Iran (1953).

1960s: the Cuban Revolution and the U.S. response

"The slogan 'we will not allow another Cuba' hides the possibility of perpetrating aggressions without fear of reprisal, such as the one carried out against the Dominican Republic or before that the massacre in Panama – and the clear warning stating that Yankee troops are ready to intervene anywhere in America where the ruling regime may be altered, thus endangering their interests."

— Che Guevara, April 16, 1967[27]

The 1959 Cuban Revolution, headed by Fidel Castro, was one of the first defeats of the US foreign policy in Latin America. In 1961, Cuba became a member of the newly created Non-Aligned Movement, which succeeded the 1955 Bandung Conference. After the implementation of several economic reforms, including complete nationalizations, by Cuba's government, US trade restrictions on Cuba increased. The U.S. halted Cuban sugar imports, on which Cuba's economy depended the most, and refused to supply its former trading partner with much needed oil, creating a devastating effect on the island's economy. In March 1960, tensions increased when the freighter La Coubre exploded in Havana harbor, killing over 75 people. Fidel Castro blamed the United States and compared the incident to the 1898 sinking of the USS Maine (ACR-16), which had precipitated the Spanish–American War, though admitting he could provide no evidence for his accusation.[28] That same month, President Dwight D. Eisenhower authorized the CIA to organize, train, and equip Cuban refugees as a guerrilla force to overthrow Castro, which would lead to the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion.[29][30]

Every time the Cuban government nationalized US properties, the US government took countermeasures, resulting in the prohibition of all exports to Cuba on 19 October 1960. Consequently, Cuba began to consolidate trade relations with the Soviet Union, leading the US to break off all remaining official diplomatic relations. Later that year, U.S. diplomats Edwin L. Sweet and Wiliam G. Friedman were arrested and expelled from the island having been charged with "encouraging terrorist acts, granting asylum, financing subversive publications and smuggling weapons". The U.S. began the formulation of new plans aimed at destabilizing the Cuban government, collectively known as "The Cuban Project" (aka Operation Mongoose). This was to be a co-ordinated program of political, psychological and military sabotage, involving intelligence operations as well as assassination attempts on key political leaders. The Cuban project also proposed false flag attacks, known as Operation Northwoods. A U.S. Senate Select Intelligence Committee report later confirmed over eight attempted plots to kill Castro between 1960 and 1965, as well as additional plans against other Cuban leaders.[31]

We (the U.S.) have not only supported a dictatorship in Cuba – we have propped up dictators in Venezuela, Argentina, Colombia, Paraguay and the Dominican Republic. We not only ignored poverty and distress in Cuba – we have failed in the past eight years to relieve poverty and distress throughout the hemisphere.

— President John F. Kennedy, October 6, 1960[32]

Beside this aggressive policy towards Cuba, John F. Kennedy tried to implement in 1961 the Alliance for Progress, an economic aid program which proved to be too shy. In the same time, the U.S. suspended economic and/or broke off diplomatic relations with several dictatorships between 1961 and JFK's assassination in 1963, including Argentina, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru. But these suspensions were imposed only temporarily, for periods of only three weeks to six months. However, the US finally decided it best to train Latin American militaries in counter-insurgency tactics at the School of the Americas. In effect, the Alliance for Progress included U.S. programs of military and police assistance to counter Communism, including Plan LASO in Colombia.

The nuclear arms race brought the two superpowers to the brink of nuclear war. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy responded to the installation of nuclear missiles in Cuba with a naval blockade—a show of force that brought the world close to nuclear war.[33] The Cuban Missile Crisis showed that neither superpower was ready to use nuclear weapons for fear of the other's retaliation, and thus of mutually assured destruction. The aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis led to the first efforts at nuclear disarmament and improving relations. (Palmowski)

By 1964, under President Johnson, the program to discriminate against dictatorial regimes ceased. In March 1964 the US supported a military coup in Brazil, overthrowing left-wing president João Goulart, and was prepared to help if called upon under Operation Brother Sam.[34] The next year, the US dispatched 24,000 soldiers to the Dominican Republic to prevent a possible left-wing take over under Operation Power Pack.

Through the Office of Public Safety, an organization dependent of the USAID and close to the CIA, the US assisted Latin American security forces, training them in interrogation methods, riot control, and sending them equipment. Dan Mitrione, in Uruguay, became infamous for his systematic use of torture.

1970s

Following the 1959 Cuban Revolution and the local implementation in several countries of Che Guevara's foco theory, the US waged a war in South America[citation needed] against what it called "Communist subversives", leading to support of coups against democratically elected presidents such as the backing of the Chilean right wing, which would culminate with Augusto Pinochet's 1973 Chilean coup against democratically-elected Salvador Allende. By 1976, all of South America was covered by similar military dictatorships, called juntas. In Paraguay, Alfredo Stroessner had been in power since 1954; in Brazil, left-wing President João Goulart was overthrown by a military coup in 1964 with the assistance of the US in what was known as Operation Brother Sam; in Bolivia, General Hugo Banzer overthrew leftist General Juan José Torres in 1971; in Uruguay, considered the "Switzerland" of South America, Juan María Bordaberry seized power in the 27 June 1973 coup. In Peru, leftist General Velasco Alvarado in power since 1968, planned to use the recently empowered Peruvian military to overwhelm Chilean armed forces in a planned invasion of Pinochetist Chile. A "Dirty War" was waged all over the subcontinent, culminating with Operation Condor, an agreement between security services of the Southern Cone and other South American countries to repress and assassinate political opponents. The armed forces also took power in Argentina in 1976,[35] and then supported the 1980 "Cocaine Coup" of Luis García Meza Tejada in Bolivia, before training the "Contras" in Nicaragua, where the Sandinista National Liberation Front, headed by Daniel Ortega, had taken power in 1979, as well as militaries in Guatemala and in El Salvador. In the frame of Operation Charly, supported by the US, the Argentine military exported state terror tactics to Central America, where the "dirty war" was waged until well into the 1990s, making hundreds of thousands "disappeared".

With the election of President Jimmy Carter in 1977, the US moderated for a short time its support to authoritarian regimes in Latin America. It was during that year that the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, an agency of the OAS, was created. At the same time, voices in the US[who?] began to denounce Pinochet's violation of human rights, in particular after the 1976 assassination of former Chilean minister Orlando Letelier in Washington D.C.

1980s–1990s: democratization and the Washington Consensus

The inauguration of Ronald Reagan in 1981 meant a renewed support for right-wing authoritarian regimes in Latin America. In the 1980s, the situation progressively evolved in the world as in South America, despite a renewal of the Cold War from 1979 to 1985, the year during which Mikhail Gorbachev replaced Konstantin Chernenko as leader of the USSR, and began to implement the glasnost and the perestroika democratic-inspired reforms. South America saw various states returning progressively to democracy. This democratization of South America found a symbol in the OAS' adoption of Resolution 1080 in 1991, which requires the Secretary General to convene the Permanent Council within ten days of a coup d'état in any member country. However, at the same time, Washington started to aggressively pursue the "War on Drugs", which included the invasion of Panama in 1989 to overthrow Manuel Noriega, who had been a long-time ally of the US and had even worked for the CIA before his reign as leader of the country. The "War on Drugs" was later expanded through Plan Colombia in the late 1990s and the Mérida Initiative in Mexico and central america.

Reagan's support of British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher during the 1982 Malvinas/Falklands War against the military junta in Argentina had a key role in the change of relations between Washington and Buenos Aires, which had been actively helping Reagan when the Argentine intelligence service was training and arming the Nicaraguan Contras against the Sandinista government (Operation Charly). The 601 Intelligence Battalion, for example, trained Contras at Lepaterique base in Honduras, under the supervision of US ambassador John Negroponte. While the US were fighting against Nicaragua, leading to the 1986 Nicaragua v. United States case before the International Court of Justice, Washington, D.C. supported authoritarian regimes in Guatemala and Salvador. The support to General Ríos Montt during the Guatemalan Civil War and the alliance with José Napoleón Duarte during the Salvadoran Civil War were legitimized by the Reagan administration as full part of the Cold War, although other allies strongly criticized this assistance to dictatorships (i.e., the French Socialist Party's 110 Propositions).

In fact, many Latin American countries view the 1982 conflict as a clear example of how the so called Hemispheric relations works.[36] A deep weakening of hemispheric relations occurred due to the US support given, without mediation, to the United Kingdom during the Malvinas/Falklands war in 1982. Some argue this definitively turned the TIAR into a dead letter. In 2001, the United States invoked the Rio Treaty after the 11 September attacks, but Latin American democracies did not join the War on Terror. (Furthermore, Mexico withdrew from the treaty in 2001 citing the Falklands example.)

On the economic plane, hardly affected by the 1973 oil crisis, the refusal of Mexico in 1983 to pay the interest of its debt led to the Latin American debt crisis and subsequently to a shift from the Import substitution industrialization policies followed by most countries to export-oriented industrialization, which was encouraged by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the World Trade Organization (WTO). While globalization was making its effects felt in the whole world, the 1990s were dominated by the Washington Consensus, which imposed a series of neo-liberal economic reforms in Latin America. The First Summit of the Americas, held in Miami in 1994, resolved to establish a Free Trade Area of the Americas (ALCA, Área de Libre Comercio de las Américas) by 2005. The ALCA was supposed to be the generalization of the North American Free Trade Agreement between Canada, the US and Mexico, which came into force in 1994. Opposition to both NAFTA and ALCA was symbolized during this time by the Zapatista Army of National Liberation insurrection, headed by Subcomandante Marcos, which became active on the day that NAFTA went into force (1 January 1994) and declared itself to be in explicit opposition to the ideology of globalization or neoliberalism, which NAFTA symbolized.

2000s: Pink Tide

The political context evolved again in the 2000s, with the election in several South American countries of socialist governments.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45] This "pink tide" thus saw the successive elections of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela (1998), Lula in Brazil (2002), Néstor Kirchner in Argentina (2003), Tabaré Vázquez in Uruguay (2004), Evo Morales in Bolivia (2005) (re-elected with 64.22% of the vote in Bolivian general election, 2009), Michelle Bachelet in Chile (2006), Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua (2006), Rafael Correa in Ecuador (2007), Fernando Lugo in Paraguay (August 15, 2008), José Mujica in Uruguayan general election, 2009, Ollanta Humala in Peru (June 5, 2011) and most recently Luis Guillermo Solís in Costa Rica (2014). Although these leaders vary in their policies and attitude towards both Washington, D.C. and neoliberalism, while the states they govern also have different agendas and long-term historic tendencies, which can lead to rivalry and open contempt between themselves, they seem to have agreed on refusing the ALCA and on following a regional integration without the United States' overseeing the process.[46] In particular, Chávez and Morales seem more disposed to ally together, while Kirchner and Lula, who has been criticized by the left-wing in Brazil, including by the Movimento dos Sem Terra (MST) landless peasants movement (who, however, did call to vote for him on his second term[47][48]), are seen as more centered. The state of Bolivia also has seen some friction with Brazil, while Chile has historically followed its own policy, distinct from other South American countries and closer to the United States. Thus, Nouriel Roubini, professor of economics at New York University, declared in a May 2006 interview:

"On one side, you have a number of administrations that are committed to moderate economic reform. On the other, you've had something of a backlash against the Washington Consensus [a set of liberal economic policies that Washington-based institutions urged Latin American countries to follow, including privatization, trade liberalization and fiscal discipline] and some emergence of populist leaders"[49]

In the same way, although a leader such as Chávez verbally attacked the George W. Bush administration as much as the latter attacked him, and claimed to be following a democratic socialist Bolivarian Revolution, the geo-political context has changed a lot since the 1970s. Larry Birns, director of the Council on Hemispheric Affairs, thus stated:

"La Paz has found itself at the economic and political nexus of the pink tide, linked by ideology to Caracas, but economically bound to Brasilia and Buenos Aires. One thing that Morales knew, however, was that he couldn’t repudiate his campaign pledges to the electorate or deprive Bolivia of the revenue that is so urgently needed.[46]

One sign of the US setback in the region has been the OEA 2005 Secretary General election. For the first time in the OEA's history, Washington's candidate was refused by the majority of countries, after two stale-mate between José Miguel Insulza, member of the Socialist Party of Chile and former Interior Minister of the latter country, and Luis Ernesto Derbez, member of the conservative National Action Party (PAN) and former Foreign Minister of Mexico. Derbez was explicitly supported by the US, Canada, Mexico, Belize, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Bolivia (then presided by Carlos Mesa), Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, while Chilean minister José Insulza was supported by all the Southern Cone countries, as well as Brazil, Ecuador, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic. José Insulza was finally elected at the third turn, and took office on 26 May 2005

Free trade and others regional integration

While the Free Trade Area of the Americas (ALCA) was abandoned after the 2005 Mar del Plata Summit of the Americas, which saw protests against the venue of US President George H. W. Bush, including Argentine piqueteros, free trade agreements were not abandoned. Regional economic integration under the sign of neoliberalism continued: under the Bush administration, the United States, which had signed two free-trade agreements with Latin American countries, signed eight further agreements, reaching a total of ten such bilateral agreements (including the United States-Chile Free Trade Agreement in 2003, the Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement in 2006, etc.). Three others, including the Peru-United States Free Trade Agreement signed in 2006, are awaiting for ratification by the US Congress.[50]

The Cuzco Declaration, signed a few weeks before at the Third South American Summit, announced the foundation of the Union of South American Nations (Unasul-Unasur) grouping Mercosul countries and the Andean Community and which as the aim of eliminating tariffs for non-sensitive products by 2014 and sensitive products by 2019. On the other hand, the CAFTA-DR free-trade agreement (Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement) was ratified by all countries except Costa Rica. The president of the latter country, Óscar Arias, member of the National Liberation Party and elected in February 2006, pronounced himself in favor of the agreement.[citation needed] Costa Rica then held a national referendum in which the population voted to approve CAFTA, which was then done by the parliament. Canada, which also has a free-trade agreement with Costa Rica, has also been negotiating such an agreement with Central American country, named Canada Central American Free Trade Agreement.

On the other hand, Chile, which has long followed a policy differing from that of its neighbors}, has signed the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership (aka P4 free-trade agreement) with Brunei, New Zealand and Singapore. The P4 came into force in May 2006. All signatory countries are member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. The United States will be joining the group as well.[citation needed]

Bilateral investment treaties

Apart from binational free-trade agreements, the US has also signed a number of bilateral investment treaties (BIT) with Latin American countries, establishing the conditions of foreign direct investment. These treaties include "fair and equitable treatment", protection from expropriation, free transfer of means and full protection and security. Critics point out that US negotiators can control the pace, content and direction of bilateral negotiations with individual countries more easily than they can with larger negotiating frameworks.[51]

In case of a disagreement between a multinational firm and a state over some kind of investment made in a Latin American country, the firm may depose a lawsuit before the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (International Center for the Resolution of Investment Disputes), which is an international court depending on the World Bank. Such a lawsuit was deposed by the US-based multinational firm Bechtel following its expulsion from Bolivia during the Cochabamba protests of 2000. Local population had demonstrated against the privatization of the water company, requested by the World Bank, after poor management of the water by Bechtel. Thereafter, Bechtel requested $50 millions from the Bolivian state in reparation. However, the firm finally decided to drop the case in 2006 after an international protest campaign.[52]

Such BIT were passed between the US and numerous countries (the given date is not of signature but of entrance in force of the treaty): Argentina (1994), Bolivia (2001), Ecuador (1997), Grenada (1989), Honduras (2001), Jamaica (1997), Panama (1991, amended in 2001), Trinidad and Tobago (1996). Others where signed but not ratified: El Salvador (1999), Haiti (1983 – one of the earliest, preceded by Panama), Nicaragua (1995).

The ALBA

In reply to the ALCA, Chavez initiated the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA). Venezuela, Cuba and Bolivia signed the TCP (or People's Trade Agreement), while Venezuela, a main productor of natural gas and of petroleum (it is member of the OPEC) has signed treaties with Argentina, Brazil and Nicaragua, where Daniel Ortega, former leader of the Sandinistas, was elected in 2006 – Ortega, however, cut down his anti-imperialist and socialist discourse, and is hotly controversial; both on the right-wing and on the left-wing. Chávez also implemented the Petrocaribe alliance, signed by 12 of the 15 members of the Caribbean Community in 2005. When Hurricane Katrina ravaged Florida and Louisiana, Chávez, who called the "Yanqui Empire" a "paper tiger", even ironically proposed to provide "oil-for-the-poor" to the US after Hurricane Katrina the same year, through Citgo, a subsidiary of PDVSA the state-owned Venezuelan petroleum company, which has 14,000 gas stations and owns eight oil refineries in the US.[53][54]

Another rift with the ALBA and the U.S. occurred when the former rejected claims of U.S. intervention in the December 9, 2008 Nicaraguan elections. A strong ALBA communiqué said: "We strongly reject the U.S. intervention in the internal issues of Nicaragua and we reaffirm that past elections are of exclusive competence of the Nicaraguan People and their institutions." Alba said in the communique published by the Venezuelan Foreign Ministry. President Daniel Ortega, as well as the FSLN, have given examples of democracy, when contending at elections during the 1980s and peacefully giving the government to their successors.[55]

The U.S. military coalition in Iraq

In June 2003, some 1,200 troops from Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua joined forces along with Spaniard forces (1,300 troops) to form the Plus Ultra Brigade in Iraq. The Brigade was dissolved on April 2004 following the retirement of Spain from Iraq, and all Latin American nations, except El Salvador, withdrew their troops.

In September 2005, it was revealed that Triple Canopy, Inc., a private military company present in Iraq, was training Latin American mercenaries in Lepaterique in Honduras.[56] Lepaterique was a former training base for the Contras. 105 Chilean mercenaries were deported from the country. According to La Tribuna Honduran newspaper, in one day in November, Your Solutions shipped 108 Hondurans, 88 Chileans and 16 Nicaraguans to Iraq.[57] Approximatively 700 Peruvians, 250 Chileans and 320 Hondurans work in Baghdad's Green Zone for Triple Canopy, paid half price in comparison to North-American employees. The news also attracted attention in Chile, when it became known that retired military Marina Óscar Aspe worked for Triple Canopy. The latter had taken part to the assassination of Marcelo Barrios Andrade, a 21-year-old member of the FPMR, who is on the list of victims of the Rettig Report – while Marina Óscar Aspe is on the list of the 2001 Comisión Ética contra la Tortura (2001 Ethical Commission Against Torture). Triple Canopy also has a subsidiary in Peru.[56]

In July 2007, Salvadoran president Antonio Saca reduced the number of deployed troops in Iraq from 380, to 280 soldiers. Four Salvadoran soldiers died in different situations since deployment in 2003, but on the bright side, more than 200 projects aimed to rebuild Iraq were completed.[58]

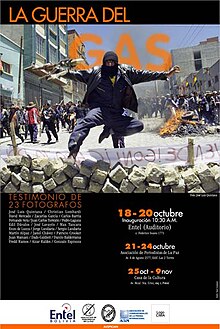

Bolivia's nationalization of natural resources

The struggle for natural resources and the US defense of its commercial interests has not ceased since the zenith period of the banana republics supported by the US. The general context has changed significantly and each country's approach has evolved accordingly. Thus, the Bolivian Gas War in 2003–04 was sparked after projects by the Pacific LNG consortium to export natural gas – Bolivia possessing the second largest natural gas reserves in South America after Venezuela – to California (Baja California and US California) via Chile, resented in Bolivia since the War of the Pacific (1879–1884) which deprived it of an access to the Pacific Ocean. The ALCA was also opposed during the demonstrations, headed by the Bolivian Workers' Center and Felipe Quispe's Indigenous Pachakuti Movement (MIP).

A proof of the new geopolitical context can be seen in Evo Morales' announcement, in concordance with his electoral promises, of the nationalization of gas reserves, the second highest in South America after Venezuela. First of all, he carefully warned that they would not take the form of expropriations or confiscations, maybe fearing a violent response. The nationalizations, which, according to Vice President Álvaro García, are supposed to make the government's energy-related revenue jump to $780 million in the following year, expanding nearly sixfold from 2002,[60] led to criticisms from Brazil, which Petrobras company is one of the largest foreign investors in Bolivia, controlling 14 percent of the country's gas reserves.[61] Bolivia is one of the poorest countries in South America and was heavily affected by protests in the 1980s–90s, largely due to the shock therapy enforced by previous governments,[46] and also by resentment concerning the coca eradication program – coca is a traditional plant for the Native Quechua and Aymara people, who use it for therapeutical (against altitude sickness) and cultural purposes. Thus, Brazil's Energy Minister, Silas Rondeau, reacted to Morales' announcement by condemning the move as "unfriendly."[62] According to Reuters, "Bolivia's actions echo what Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, possibly Morales' biggest ally, did in the world's fifth-largest oil exporter with forced contract migrations and retroactive tax hikes – conditions that major oil companies largely agreed to accept." The Bolivian gas company YPFB, privatized by former President Gonzalo Sanchez de Losada, was to pay foreign companies for their services, offering about 50 percent of the value of production, although the decree indicated that companies exploiting the country's two largest gas fields would get just 18 percent. After initially hostile reactions, Repsol "expressed its willingness to cooperate with the Bolivian government," while Petrobras retreated its call to cancel new investment in Bolivia.[46] However, still according to Larry Birns, "The nationalization's high media profile could force the [US] State Department to take a tough approach to the region, even to the point of mobilizing the CIA and the U.S. military, but it is more likely to work its way by undermining the all-important chink in the armor – the Latin American armed forces."[46]

See also

- American Empire

- Foreign relations of the United States

- List of United States military bases

- List of free trade agreements

- Organization of American States

Binational relationships

- Argentina–United States relations

- Bolivia-United States relations

- Brazil–United States relations

- Chile–United States relations

- Colombia–United States relations

- Cuba–United States relations

- Ecuador–United States relations

- Mexico–United States relations

- Nicaragua–United States relations

- United States–Venezuela relations

References

- ^ "Latin America's Left Turn". foreignaffairs.org. Retrieved March 23, 2008.

- ^ Anderson, Mark. C. "What's to Be Done With 'Em? Images of Mexican Cultural Backwardness, Racial Limitations and Moral Decrepitude in the United States Press 1913-1915", Mexican Studies, Winter Vol. 14, No. 1 (1998):30.

- ^ "Panama: A Country Study". Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1987.

- ^ King (2007:249)

- ^ Graff, Henry F., Grover Cleveland (2002). ISBN 0-8050-6923-2. pp123-25

- ^ Ferrell, Robert H. "Monroe Doctrine". ap.grolier.com. Retrieved October 31, 2008.

- ^ Mark Barnes (2010). The Spanish–American War and Philippine Insurrection, 1898–1902. Routledge. p. 67.

- ^ W. Joseph Campbell, Yellow journalism: Puncturing the myths, defining the legacies (2001).

- ^ Beede 1994, p. 148.

- ^ Beede 1994, p. 120.

- ^ Pérez 1998, p. 89 states: "In the larger view, the Cuban insurrection had already brought the Spanish army to the brink of defeat. During three years of relentless war, the Cubans had destroyed railroad lines, bridges, and roads and paralyzed telegraph communications, making it all but impossible for the Spanish army to move across the island and between provinces. [The] Cubans had, moreover, inflicted countless thousands of casualties on Spanish soldiers and effectively driven Spanish units into beleaguered defensive concentrations in the cities, there to suffer the further debilitating effects of illness and hunger."

- ^ "Military Book Reviews". StrategyPage.com. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Dyal, Carpenter & Thomas 1996, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Benjamin R. Beede (2013). The War of 1898 and U.S. Interventions, 1898T1934: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 289.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: Official Declarations of War by Congress". senate.gov. June 29, 2015.

- ^ Edmund Morris, "'A Matter Of Extreme Urgency' Theodore Roosevelt, Wilhelm II, and the Venezuela Crisis of 1902," Naval War College Review (2002) 55#2 pp 73–85

- ^ Shoultz, Lars. Beneath the United States pg. 166–169. The U.S. violated Colombian sovereignty in that they supported the secession of Panama through the use of the U.S. navy. Senator Edward Carmack was quoted as saying, "There never was any real insurrection in Panama. To all intents and purposes [sic] there was but one man in that insurrection, and that man was the President of the United States."

- ^ Glickman, Robert Jay. Norteamérica vis-à-vis Hispanoamérica: ¿oposición o asociación? Toronto: Canadian Academy of the Arts, 2005.

- ^ Friedrich Katz, The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1981, p. 563.

- ^ Katz, Secret War in Mexico, p. 564.

- ^ John Womack, Jr. "The Mexican Revolution" in Mexico Since Independence, ed. Leslie Bethell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991, p. 131.

- ^ Roosevelt, Franklin Delano. "First Inaugural Address." Washington, D.C. March 4, 1933

- ^ Edgar B. Nixon, ed. Franklin D. Roosevelt and Foreign Affairs: Volume I, 559–60.

- ^ Adam, Thomas, ed. (2005). Transatlantic relations series. Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History : a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Vol. II. ABC-CLIO. pp. 181–2. ISBN 1-85109-628-0.

- ^ Inter-American economic affairs Volumes 15–16, by Institute of Inter-American Studies in Washington, D.C., Inter-American Affairs Press, 1975

- ^ LaFeber, Walter. America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1992 7th ed. (1993)

- ^ Latin America and the United States: A Documentary History, by Robert H. Holden & Eric Zolov, Oxford University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-19-512994-6

- ^ Fursenko and Naftali, The Cuban Missile Crisis. p40–47

- ^ Bay of Pigs Global Security.org

- ^ "Castro marks Bay of Pigs victory" BBC News

- ^ Interim Report: Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders Original document

- ^ "Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy at Democratic Dinner, Cincinnati, Ohio, October 6, 1960" from the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library

- ^ "Cold War", Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Craig Calhoun, ed. Oxford University Press. 2002.

- ^ Bell, P. M. H. (2001). The World Since 1945. Oxford University Press. 0340662360.

- ^ According to the National Security Archive, the Argentine junta led by Jorge Rafael Videla, believed it had United States' approval for its all-out assault on the left in the name of "national security doctrine". The U.S. Embassy in Buenos Aires complained to Washington that the Argentine officers were "euphoric" over signals from high-ranking U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. See ARGENTINE MILITARY BELIEVED U.S. GAVE GO-AHEAD FOR DIRTY WAR, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 73 – Part II, CIA classified documents released in 2002

- ^ "Revista Fuerzas Armadas y Sociedad – The Brazilian foreign policy and the hemispheric security". Socialsciences.scielo.org. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ "Correa highligts new socialism in Latin America". Cre.com.ec. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ "Sao Paulo Journal; Lula's Progress: From Peasant Boy to President?". New York Times. December 27, 1993. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ "Venezuela championing a new socialist agenda". Findarticles.com. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ "Argentina's Néstor Kirchner: Peronism Without the Tears". Coha.org. January 27, 2006. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ Socialist takes oath as Uruguay president[dead link]

- ^ Neo-liberalism and the New Socialism – speech by Alvaro Garcia Linera (Vicepresident of Bolivia)[dead link]

- ^ Rohter, Larry (March 11, 2006). "Chile's Socialist President Exits Enjoying Wide Respect". The New York Times. Chile. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ "Daniel Ortega – the Sandinista is back as president of Nicaragua". Internationalanalyst.wordpress.com. June 13, 2007. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ "Paraguay's new president believes in God and 21st-Century Socialism". En.rian.ru. April 23, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e The Aftermath of Bolivia’s Gas Golpe, Larry Birns and Michael Lettieri, Political Affairs magazine, July 5, 2006

- ^ Interview with Geraldo Fontes of the MST, In Motion magazine, March 26, 2005

- ^ MST calls for Congress-Brazilian people alliance, Radiobras, June 23, 2005

- ^ Bolivia's Nationalization of Oil and Gas, US Council on Foreign Relations, May 12, 2006

- ^ Le Figaro, March 8, 2007, George Bush défie Hugo Chavez sur son terran Template:Fr icon

- ^ "Latin America: Bilateral Trade Deals Favor U.S. Interests". Stratfor.com. November 12, 2002. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ Bechtel vs Bolivia, The Democracy Center, URL accessed on March 14, 2007

- ^ Chavez offers oil to Europe's poor, The Observer, May 14, 2006

- ^ Chavez' Surprise for Bush, New York Daily News, September 18, 2005, mirrored by Common Dreams

- ^ http://istarmedia.net/ (May 25, 2007). "ALBA Rejects U.S. Intervention in Nicaraguan Elections". Insidecostarica.com. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|author= - ^ a b Capítulos desconocidos de los mercenarios chilenos en Honduras camino de Iraq, La Nación, September 25, 2005 – URL accessed on February 14, 2007 Template:Es icon

- ^ Latin American mercenaries guarding Baghdad’s Green Zone, December 28, 2005

- ^ Template:Es icon Contingente IX con menos soldados a Iraq, La Prensa Grafica, July 15, 2007

- ^ The U.S. Department of State issued a statement on October 13 declaring its support for Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, calling for "Bolivia's political leaders [to] publicly express their support for democratic and constitutional order. The international community and the United States will not tolerate any interruption of constitutional order and will not support any regime that results from undemocratic means." This statement followed the death of 60 Bolivians during the police and army repression, in particular in El Alto, the Aymara suburb of La Paz "Call for Respect for Constitutional Order in Bolivia". US State Department. October 13, 2003. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved April 2006.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Bolivia's military takes control of gas fields". Reuters. May 2, 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2006.

- ^ "Bolivia gas under state control". BBC News. May 2, 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2006.

- ^ "Ministro de Minas e Energia classifica decreto boliviano de "inamistoso"" (in Portuguese). Folha de S.Paulo. May 2, 2006. Retrieved May 2, 2006.

Further reading

- LaRosa, Michael J. and Frank O. Mora. Neighborly Adversaries: Readings in U.S.–Latin American Relations (2006)

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390.

- Mellander, Gustavo A. (1971). The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

- When States Kill: Latin America, the U.S., and Technologies of Terror, ed. by Cecilia Menjivar and Nestor Rodriguez, University of Texas Press, 2005

- Rodríguez Hernández, Saúl, La influencia de los Estados Unidos en el Ejército Colombiano, 1951–1959, Medellín, La Carreta, 2006, ISBN 958-97811-3-6.

External links

- Latin America : Trouble at the U.S. Doorstep? from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Tensions Rise in Latin America over US Military Plan to Use Three Bases in Colombia – video by Democracy Now!

- "How Obama can Earn his Nobel Peace Prize" by Ariel Dorfman, The Los Angeles Times

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).