Electric charge

| Articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

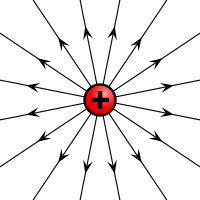

Electric charge is the physical property of matter that causes it to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. There are two types of electric charges: positive and negative. Like charges repel and unlike attract. An object (one not made of antimatter) is negatively charged if it has an excess of electrons, and is otherwise positively charged or uncharged. The SI derived unit of electric charge is the coulomb (C). In electrical engineering, it is also common to use the ampere-hour (Ah), and, in chemistry, it is common to use the elementary charge (e) as a unit. The symbol Q often denotes charge. Early knowledge of how charged substances interact is now called classical electrodynamics, and is still accurate for problems that don't require consideration of quantum effects.

The electric charge is a fundamental conserved property of some subatomic particles, which determines their electromagnetic interaction. Electrically charged matter is influenced by, and produces, electromagnetic fields. The interaction between a moving charge and an electromagnetic field is the source of the electromagnetic force, which is one of the four fundamental forces (See also: magnetic field).

Twentieth-century experiments demonstrated that electric charge is quantized; that is, it comes in integer multiples of individual small units called the elementary charge, e, approximately equal to 1.602×10−19 coulombs (except for particles called quarks, which have charges that are integer multiples of e/3). The proton has a charge of +e, and the electron has a charge of -e. The study of charged particles, and how their interactions are mediated by photons, is called quantum electrodynamics.

Overview

Charge is the fundamental property of forms of matter that exhibit electrostatic attraction or repulsion in the presence of other matter. Electric charge is a characteristic property of many subatomic particles. The charges of free-standing particles are integer multiples of the elementary charge e; we say that electric charge is quantized. Michael Faraday, in his electrolysis experiments, was the first to note the discrete nature of electric charge. Robert Millikan's oil drop experiment demonstrated this fact directly, and measured the elementary charge.

By convention, the charge of an electron is −1, while that of a proton is +1. Charged particles whose charges have the same sign repel one another, and particles whose charges have different signs attract. Coulomb's law quantifies the electrostatic force between two particles by asserting that the force is proportional to the product of their charges, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

The charge of an antiparticle equals that of the corresponding particle, but with opposite sign. Quarks have fractional charges of either −1/3 or +2/3, but free-standing quarks have never been observed (the theoretical reason for this fact is asymptotic freedom).

The electric charge of a macroscopic object is the sum of the electric charges of the particles that make it up. This charge is often small, because matter is made of atoms, and atoms typically have equal numbers of protons and electrons, in which case their charges cancel out, yielding a net charge of zero, thus making the atom neutral.

An ion is an atom (or group of atoms) that has lost one or more electrons, giving it a net positive charge (cation), or that has gained one or more electrons, giving it a net negative charge (anion). Monatomic ions are formed from single atoms, while polyatomic ions are formed from two or more atoms that have been bonded together, in each case yielding an ion with a positive or negative net charge.

During formation of macroscopic objects, constituent atoms and ions usually combine to form structures composed of neutral ionic compounds electrically bound to neutral atoms. Thus macroscopic objects tend toward being neutral overall, but macroscopic objects are rarely perfectly net neutral.

Sometimes macroscopic objects contain ions distributed throughout the material, rigidly bound in place, giving an overall net positive or negative charge to the object. Also, macroscopic objects made of conductive elements, can more or less easily (depending on the element) take on or give off electrons, and then maintain a net negative or positive charge indefinitely. When the net electric charge of an object is non-zero and motionless, the phenomenon is known as static electricity. This can easily be produced by rubbing two dissimilar materials together, such as rubbing amber with fur or glass with silk. In this way non-conductive materials can be charged to a significant degree, either positively or negatively. Charge taken from one material is moved to the other material, leaving an opposite charge of the same magnitude behind. The law of conservation of charge always applies, giving the object from which a negative charge is taken a positive charge of the same magnitude, and vice versa.

Even when an object's net charge is zero, charge can be distributed non-uniformly in the object (e.g., due to an external electromagnetic field, or bound polar molecules). In such cases the object is said to be polarized. The charge due to polarization is known as bound charge, while charge on an object produced by electrons gained or lost from outside the object is called free charge. The motion of electrons in conductive metals in a specific direction is known as electric current.

Units

The SI unit of quantity of electric charge is the coulomb, which is equivalent to about 6.242×1018 e (e is the charge of a proton). Hence, the charge of an electron is approximately −1.602×10−19 C. The coulomb is defined as the quantity of charge that has passed through the cross section of an electrical conductor carrying one ampere within one second. The symbol Q is often used to denote a quantity of electricity or charge. The quantity of electric charge can be directly measured with an electrometer, or indirectly measured with a ballistic galvanometer.

After finding the quantized character of charge, in 1891 George Stoney proposed the unit 'electron' for this fundamental unit of electrical charge. This was before the discovery of the particle by J.J. Thomson in 1897. The unit is today treated as nameless, referred to as "elementary charge", "fundamental unit of charge", or simply as "e". A measure of charge should be a multiple of the elementary charge e, even if at large scales charge seems to behave as a real quantity. In some contexts it is meaningful to speak of fractions of a charge; for example in the charging of a capacitor, or in the fractional quantum Hall effect.

In systems of units other than SI such as cgs, electric charge is expressed as combination of only three fundamental quantities (length, mass, and time), and not four, as in SI, where electric charge is a combination of length, mass, time, and electric current.[citation needed]

History

As reported by the ancient Greek mathematician Thales of Miletus around 600 BC, charge (or electricity) could be accumulated by rubbing fur on various substances, such as amber. The Greeks noted that the charged amber buttons could attract light objects such as hair. They also noted that if they rubbed the amber for long enough, they could even get an electric spark to jump. This property derives from the triboelectric effect.

In 1600, the English scientist William Gilbert returned to the subject in De Magnete, and coined the New Latin word electricus from ἤλεκτρον (ēlektron), the Greek word for amber, which soon gave rise to the English words "electric" and "electricity." He was followed in 1660 by Otto von Guericke, who invented what was probably the first electrostatic generator. Other European pioneers were Robert Boyle, who in 1675 stated that electric attraction and repulsion can act across a vacuum; Stephen Gray, who in 1729 classified materials as conductors and insulators; and C. F. du Fay, who proposed in 1733[1] that electricity comes in two varieties that cancel each other, and expressed this in terms of a two-fluid theory. When glass was rubbed with silk, du Fay said that the glass was charged with vitreous electricity, and, when amber was rubbed with fur, the amber was charged with resinous electricity. In 1839, Michael Faraday showed that the apparent division between static electricity, current electricity, and bioelectricity was incorrect, and all were a consequence of the behavior of a single kind of electricity appearing in opposite polarities. It is arbitrary which polarity is called positive and which is called negative. Positive charge can be defined as the charge left on a glass rod after being rubbed with silk.[2]

One of the foremost experts on electricity in the 18th century was Benjamin Franklin, who argued in favour of a one-fluid theory of electricity. Franklin imagined electricity as being a type of invisible fluid present in all matter; for example, he believed that it was the glass in a Leyden jar that held the accumulated charge. He posited that rubbing insulating surfaces together caused this fluid to change location, and that a flow of this fluid constitutes an electric current. He also posited that when matter contained too little of the fluid it was "negatively" charged, and when it had an excess it was "positively" charged. For a reason that was not recorded, he identified the term "positive" with vitreous electricity and "negative" with resinous electricity. William Watson arrived at the same explanation at about the same time.

Static electricity and electric current

Static electricity and electric current are two separate phenomena. They both involve electric charge, and may occur simultaneously in the same object. Static electricity refers to the electric charge of an object and the related electrostatic discharge when two objects are brought together that are not at equilibrium. An electrostatic discharge creates a change in the charge of each of the two objects. In contrast, electric current is the flow of electric charge through an object, which produces no net loss or gain of electric charge.

Electrification by friction

This section contains close paraphrasing of an external source, https://archive.org/details/ATreatiseOnElectricityMagnetism-Volume1 (Copyvios report). (November 2014) |

When a piece of glass and a piece of resin—neither of which exhibit any electrical properties—are rubbed together and left with the rubbed surfaces in contact, they still exhibit no electrical properties. When separated, they attract each other.

A second piece of glass rubbed with a second piece of resin, then separated and suspended near the former pieces of glass and resin causes these phenomena:

- The two pieces of glass repel each other.

- Each piece of glass attracts each piece of resin.

- The two pieces of resin repel each other.

This attraction and repulsion is an electrical phenomena, and the bodies that exhibit them are said to be electrified, or electrically charged. Bodies may be electrified in many other ways, as well as by friction. The electrical properties of the two pieces of glass are similar to each other but opposite to those of the two pieces of resin: The glass attracts what the resin repels and repels what the resin attracts.

If a body electrified in any manner whatsoever behaves as the glass does, that is, if it repels the glass and attracts the resin, the body is said to be 'vitreously' electrified, and if it attracts the glass and repels the resin it is said to be 'resinously' electrified. All electrified bodies are either vitreously or resinously electrified.

An established convention in the scientific community defines vitreous electrification as positive, and resinous electrification as negative. The exactly opposite properties of the two kinds of electrification justify our indicating them by opposite signs, but the application of the positive sign to one rather than to the other kind must be considered as a matter of arbitrary convention—just as it is a matter of convention in mathematical diagram to reckon positive distances towards the right hand.

No force, either of attraction or of repulsion, can be observed between an electrified body and a body not electrified.[3]

Actually, all bodies are electrified, but may appear not electrified because of the relatively similar charge of neighboring objects in the environment. An object further electrified + or – creates an equivalent or opposite charge by default in neighboring objects, until those charges can equalize. The effects of attraction can be observed in high-voltage experiments, while lower voltage effects are merely weaker and therefore less obvious. The attraction and repulsion forces are codified by Coulomb's law (attraction falls off at the square of the distance, which has a corollary for acceleration in a gravitational field, suggesting that gravitation may be merely electrostatic phenomenon between relatively weak charges in terms of scale). See also Casimir effect.

It is now known that the Franklin-Watson model was fundamentally correct. There is only one kind of electrical charge, and only one variable is required to keep track of the amount of charge.[4] On the other hand, just knowing the charge is not a complete description of the situation. Matter is composed of several kinds of electrically charged particles, and these particles have many properties, not just charge.

The most common charge carriers are the positively charged proton and the negatively charged electron. The movement of any of these charged particles constitutes an electric current. In many situations, it suffices to speak of the conventional current without regard to whether it is carried by positive charges moving in the direction of the conventional current or by negative charges moving in the opposite direction. This macroscopic viewpoint is an approximation that simplifies electromagnetic concepts and calculations.

At the opposite extreme, if one looks at the microscopic situation, one sees there are many ways of carrying an electric current, including: a flow of electrons; a flow of electron "holes" that act like positive particles; and both negative and positive particles (ions or other charged particles) flowing in opposite directions in an electrolytic solution or a plasma.

Beware that, in the common and important case of metallic wires, the direction of the conventional current is opposite to the drift velocity of the actual charge carriers, i.e., the electrons. This is a source of confusion for beginners.

| Flavour in particle physics |

|---|

| Flavour quantum numbers |

|

| Related quantum numbers |

|

| Combinations |

|

| Flavour mixing |

Conservation of electric charge

The total electric charge of an isolated system remains constant regardless of changes within the system itself. This law is inherent to all processes known to physics and can be derived in a local form from gauge invariance of the wave function. The conservation of charge results in the charge-current continuity equation. More generally, the net change in charge density ρ within a volume of integration V is equal to the area integral over the current density J through the closed surface S = ∂V, which is in turn equal to the net current I:

Thus, the conservation of electric charge, as expressed by the continuity equation, gives the result:

The charge transferred between times and is obtained by integrating both sides:

where I is the net outward current through a closed surface and Q is the electric charge contained within the volume defined by the surface.

Relativistic invariance

Aside from the properties described in articles about electromagnetism, charge is a relativistic invariant. This means that any particle that has charge Q, no matter how fast it goes, always has charge Q. This property has been experimentally verified by showing that the charge of one helium nucleus (two protons and two neutrons bound together in a nucleus and moving around at high speeds) is the same as two deuterium nuclei (one proton and one neutron bound together, but moving much more slowly than they would if they were in a helium nucleus).[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ Two Kinds of Electrical Fluid: Vitreous and Resinous – 1733

- ^ Electromagnetic Fields (2nd Edition), Roald K. Wangsness, Wiley, 1986. ISBN 0-471-81186-6 (intermediate level textbook)

- ^ James Clerk Maxwell A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, pp. 32-33, Dover Publications Inc., 1954 ASIN: B000HFDK0K, 3rd ed. of 1891

- ^ One Kind of Charge

External links

- How fast does a charge decay?

- Science Aid: Electrostatic charge Easy-to-understand page on electrostatic charge.

- History of the electrical units.