T33 (classification)

T33 and CP3 are disability sport classification for disability athletics. The class competes using a wheelchair. The classification is one of eight for people with cerebral palsy, and one of four for people with cerebral palsy who use a wheelchair. Athletes in this class have moderate quadriplegia, and difficulty with forward trunk movement. They also may have hypertonia, ataxia and athetosis.

Definition

This classification is for disability athletics.[1] This classification is one of eight classifications for athletes with cerebral palsy, four for wheelchair athletes (T31, T32, T33, T34) and four for ambulant ones (T35, T36, T37 and T38).[2] Jane Buckley, writing for the Sporting Wheelies, describes the athletes in this classification as: "CP3, see CP-ISRA classes (appendix) Wheelchair "[1] The classification in the appendix by Buckley goes on to say "The athlete shows fair trunk movement when pushing a wheelchair, but forward trunk movement is limited during forceful pushing."[1] The Australian Paralympic Committee defines this classification as being for "Moderate quadriplegia." [3] The International Paralympic Committee defined this classification on their website in July 2016 as, "Coordination impairments (hypertonia, ataxia and athetosis)".[4]

Disability groups

Multiple types of disabilities are eligible to compete in this class. This class includes people who have have cerebral palsy, or who have had a stroke or traumatic brain injury. [5][6]

Cerebral palsy

CP3

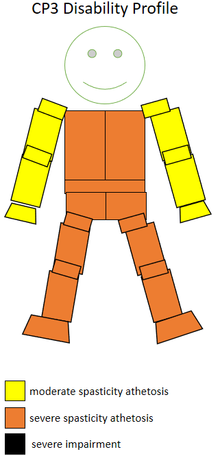

On a daily basis, CP3 sportspeople are likely to use a wheelchair. Some may be ambulant with the use of assistive devices.[7][8] While they may have good trunk control, they may have some issues with strong forward movements of their torso.[8][9] While CP2, CP3 and CP6 have similar issues with Athetoid or Ataxic, CP6 competitors have "flight" while they are ambulant in that it is possible for both feet to not be touching the ground while walking. CP2 and CP3 are unable to do this.[7] Head movement and trunk function differentiate this class from CP4. Lack of symmetry in arm movement are another major difference between the two classes, with CP3 competitors having less symmetry.[10]

Performance and rules

Wheelchairs used by this class have three wheels, with a maximum rear height of 70 centimetres (28 in) and maximum front height of 50 centimetres (20 in). Chairs cannot have mirrors or any gears. They are not allowed to have anything protruding from the back of the chair. Officials can check for this by placing the chair against a wall, where the rear wheels should touch it without obstruction. As opposed to wearing hip numbers, racers in this class wear them on the helmet. Instead of wearing bibs, these numbers are put on the back of the racing chair and the racer.[11]

History

Historically, CP3 athletes were more active in track events. Changes in the classification during the 1980s and 1990s led to most track events for CP3 racers being dropped and replaced exclusively with field events.[12][13] This has been criticized, because with the rise of commercialization of the Paralympic movement, there has been a a reduction of classes in more popular sports for people with the most severe disabilities as these classes often have much higher support costs associated with them.[14][15][16]

The classification was created by the International Paralympic Committee and has roots in a 2003 attempt to address "the overall objective to support and co-ordinate the ongoing development of accurate, reliable, consistent and credible sport focused classification systems and their implementation."[17]

For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case by case basis.[18] In case there was a need for classification or reclassification at the Games despite best efforts otherwise, athletics classification was scheduled for September 4 and September 5 at Olympic Stadium. For sportspeople with physical or intellectual disabilities going through classification or reclassification in Rio, their in competition observation event is their first appearance in competition at the Games.[18]

Governance

Classification into this class is handled by the International Paralympic Committee.[19] For national events, classification is handled by the national athletics organization.[20]

Becoming classified

Athletes with cerebral palsy or similar impairments who wish to compete in para-athletics competition must first undergo a classification assessment. During this, they both undergo a bench test of muscle coordination and demonstrate their skills in athletics, such as pushing a racing wheelchair and throwing. A determination is then made as to what classification an athlete should compete in. Classifications may be Confirmed or Review status. For athletes who do not have access to a full classification panel, Provisional classification is available; this is a temporary Review classification, considered an indication of class only, and generally used only in lower levels of competition.[21]

While some some people in this class may be ambulatory, they generally go through the classification process while using a wheelchair. This is because they often compete from a seated position.[22] Failure to do so could result in them being classified as an ambulatory class competitor.[22]

Competitors

In 2011, Almutairi Ahmad from Tunisia and born in 1994 is ranked 1 in the world in the 100 metre event.[23] Speight Louis from Great Britain and born in 1990 is ranked 2 in the world in the 100 metre event.[23] Roberts John from United States of America and born in 1983 is ranked 3 in the world in the 100 metre event.[23] Yamada Yoshihiro from Japan and born in 1979 is ranked 4 in the world in the 100 metre event.[23]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Buckley, Jane (2011). "Understanding Classification: A Guide to the Classification Systems used in Paralympic Sports". Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ "Summer Sports » Athletics". Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "Classification Information Sheet" (PDF). Sydney, Australia. 16 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "IPC Athletics Classification & Categories". www.paralympic.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ Broad, Elizabeth (2014-02-06). Sports Nutrition for Paralympic Athletes. CRC Press. ISBN 9781466507562.

- ^ "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Kategorie postižení handicapovaných sportovců". Tyden (in Czech). September 12, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "Clasificaciones de Ciclismo" (PDF). Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte (in Mexican Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ "CLASSIFICATION AND SPORTS RULE MANUAL" (PDF). CPISRA. CPISRA. January 2005. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "PARALYMPIC TRACK & FIELD: Officials Training" (PDF). USOC. United States Olympic Committee. December 11, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ Howe, David (2008-02-19). The Cultural Politics of the Paralympic Movement: Through an Anthropological Lens. Routledge. ISBN 9781134440832.

- ^ Loland, Sigmund; Skirstad, Berit; Waddington, Ivan (2006-01-01). Pain and Injury in Sport: Social and Ethical Analysis. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415357036.

- ^ Hardman, Alun R.; Jones, Carwyn (2010-12-02). The Ethics of Sports Coaching. Routledge. ISBN 9781135282967.

- ^ Brittain, Ian (2016-07-01). The Paralympic Games Explained: Second Edition. Routledge. ISBN 9781317404156.

- ^ Baker, Joe; Safai, Parissa; Fraser-Thomas, Jessica (2014-10-17). Health and Elite Sport: Is High Performance Sport a Healthy Pursuit?. Routledge. ISBN 9781134620012.

- ^ "Paralympic Classification Today". International Paralympic Committee. 22 April 2010. p. 3.

{{cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ^ "IPC Athletics Classification & Categories". www.paralympic.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ "Athletics Classification". Australian Paralympic Committee. Australian Paralympic Committee. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ^ "CLASSIFICATION Information for Athletes" (PDF). Sydney Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ a b Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- ^ a b c d "IPC Athletics Rankings Official World Rankings 2011". International Paralympic Committee. 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.