Pythagoras

Πυθαγόρας | |

|---|---|

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Pythagoreanism |

Main interests | Philosophy of mathematics |

Notable ideas | Numbers as the ultimate reality |

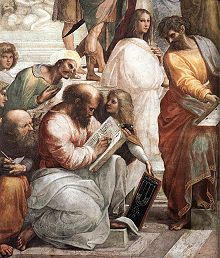

Pythagoras of Samos (approximately 582 BC–507 BC, Greek: Πυθαγόρας) was an Ionian (Greek) mathematician and philosopher, founder of the mystic, religious and scientific society called Pythagoreans. He is best known for the Pythagorean theorem which bears his name. Known as "the father of numbers", Pythagoras made influential contributions to philosophy and religious teaching in the late 6th century BC. Because legend and obfuscation cloud his work even more than with the other pre-Socratics, one can say little with confidence about his life and teachings. We do know that Pythagoras and his students believed that everything was related to mathematics and, through mathematics, everything could be predicted and measured in rhythmic patterns or cycles.

Biography

Pythagoras was born on the island of Samos (Greek West Coast), off the coast of Asia Minor. He was born to Pythais (his mother, a native of Samos) and Mnesarchus (a merchant from Tyre). As a young man, he left his native city for Crotone in Southern Italy, to escape the tyrannical government of Polycrates. According to Iamblichus, Thales, impressed with his abilities, advised Pythagoras to go to Memphis in Egypt and study with the priests there who were renowned for their wisdom. It may have been in Egypt where he learned some geometric principles which eventually inspired his discovery of the theorem that is now called by his name. This possible inspiration is presented as an example problem in the Berlin Papyrus.

Upon his migration from Samos to Crotone, Pythagoras established a secret religious society very similar to (and possibly influenced by) the earlier Orphic cult.

Pythagoras undertook a reform of the cultural life of Crotone, urging the citizens to follow virtue and form an elite circle of followers around himself. Very strict rules of conduct governed this cultural center. He opened his school to male and female students alike. Those who joined the inner circle of Pythagoras's society called themselves the Mathematikoi. They lived at the school, owned no personal possessions and were required to assume a vegetarian diet. Other students who lived in neighboring areas were also permitted to attend Pythagoras's school. Known as Akousmatics, these students were permitted to eat meat and own personal belongings.

According to Iamblichus, the Pythagoreans followed a structured life of religious teaching, common meals, exercise, reading and philosophical study. Music featured as an essential organizing factor of this life: the disciples would sing hymns to Apollo together regularly; they used the lyre to cure illness of the soul or body; poetry recitations occurred before and after sleep to aid the memory.

The history of the Pythagorean theorem that bears his name is complex. Whether Pythagoras himself proved this theorem is not known, as it was common in the ancient world to credit to a famous teacher the discoveries of his students. The earliest known mention of Pythagoras's name in connection with the theorem occurred five centuries after his death, in the writings of Cicero and Plutarch. It is also believed that the Indian mathematician Baudhayana discovered the Pythagorean Theorem around 800 BC, about 300 years before Pythagoras.

Today, Pythagoras is revered as a prophet by the Ahlu l-Tawhīd or Druze faith along with his fellow Greek, Plato.

Pythagoreans

- Main article: Pythagoreanism

Pythagoras's followers were commonly called "Pythagoreans." For the most part we remember them as philosophical mathematicians who had an influence on the beginning of axiomatic geometry, which after two hundred years of development was written down by Euclid in The Elements. The Pythagoreans observed a rule of silence called echemythia, the breaking of which was punishable by death. In his biography of Pythagoras (written seven centuries after Pythagoras's time) Porphyry stated that this silence was "of no ordinary kind." The Pythagoreans were divided into an inner circle called the mathematikoi ("mathematicians") and an outer circle called the akousmatikoi ("listeners"). Porphyry wrote "the mathematikoi learned the more detailed and exactly elaborate version of this knowledge, the akousmatikoi (were) those which had heard only the summary headings of his (Pythagoras's) writings, without the more exact exposition." According to Iamblichus, the akousmatikoi were the exoteric disciples who listened to lectures that Pythagoras gave out loud from behind a veil. The akousmatikoi were not allowed to see Pythagoras and they were not taught the inner secrets of the cult. Instead they were taught laws of behavior and morality in the form of cryptic, brief sayings that had hidden meanings. The akousmatikoi recognized the mathematikoi as real Pythagoreans, but not vice versa. After the murder of Pythagoras and a number of the mathematikoi by the cohorts of Cylon, a resentful disciple, the two groups split from each other entirely, with Pythagoras's wife Theano and their two daughters leading the mathematikoi.

Theano, daughter of the Orphic initiate Brontinus, was a mathematician in her own right. She is credited with having written treatises on mathematics, physics, medicine, and child psychology, although nothing of her writing survives. Her most important work is said to have been a treatise on the principle of the golden mean. In a time when women were usually considered property and relegated to the role of housekeeper or spouse, Pythagoras allowed women to function on equal terms in his society.

The Pythagorean society is associated with strange and superstitious prohibitions, such as not to step over a crossbar, and not to eat beans (for the inside of beans 'contained' human embryos). These rules seem like primitive superstition, similar to "walking under a ladder brings bad luck," rules one cannot help but sneeze at. The abusive epithet mystikos logos ("mystical speech") was hurled at Pythagoras even in ancient times to discredit him. The key here is that "akousmata" means "rules," so that the superstitious taboos primarily applied to the akousmatikoi, and many of the rules were probably invented after Pythagoras's death and independent from the mathematikoi (arguably the real preservers of the Pythagorean tradition). The mathematikoi placed greater emphasis on inner understanding than did the akousmatikoi, even to the extent of dispensing with certain rules and ritual practices. For the mathematikoi, being a Pythagorean was a question of innate quality and inner understanding.

Beans, black and white, were the means used in voting. The maxim "abstain from beans" was perhaps nothing more than an exhortation to not vote. If true, this would be an excellent example of how ideas can be distorted when heard second hand and taken out of context. There was also another way of dealing with the akousmata — by allegorizing them. We have a few examples of this, one being Aristotle's explanations of them: "'step not over a balance', i.e. be not covetous; 'poke not the fire with a sword', i.e. do not vex with sharp words a man swollen with anger, 'eat not heart', i.e. do not vex yourself with grief," etc. We have evidence for Pythagoreans allegorizing in this way at least as far back as the early fifth century BC. This suggests that the strange sayings were riddles for the initiated.

The Pythagoreans are known for their theory of the transmigration of souls, and also for their theory that numbers constitute the true nature of things. They performed purification rites and followed and developed various rules of living which they believed would enable their soul to achieve a higher rank among the gods. Much of their mysticism concerning the soul seem inseparable from the Orphic tradition. The Orphics advocated various purifactory rites and practices as well as incubatory rites of descent into the underworld. Pythagoras is also closely linked with Pherecydes of Syros, the man ancient commentators tend to credit as the first Greek to teach a transmigration of souls. Ancient commentators agree that Pherekydes was Pythagoras's most intimate teacher. Pherekydes expounded his teaching on the soul in terms of a pentemychos ("five-nooks," or "five hidden cavities") — the most likely origin of the Pythagorean use of the pentagram, used by them as a symbol of recognition among members and as a symbol of inner health (ugieia).

It was the Pythagoreans who discovered that the relationship between musical notes could be expressed in numerical ratios of small whole numbers (see Pythagorean tuning). The Pythagoreans elaborated on a theory of numbers the exact meaning of which is still debated among scholars.

Literary works

No texts by Pythagoras survive, although forgeries under his name — a few of which remain extant — did circulate in antiquity. Critical ancient sources like Aristotle and Aristoxenus cast doubt on these writings. Ancient Pythagoreans usually quoted their master's doctrines with the phrase autos ephe ("he himself said") — emphasizing the essentially oral nature of his teaching. Pythagoras appears as a character in the last book of Ovid's Metamorphoses , where Ovid has him expound upon his philosophical viewpoints.

Influence on Plato

Pythagoras or in a broader sense, the Pythagoreans, allegedly exercised an important influence on the work of Plato. According to R. M. Hare, his influence consists of three points: a) the platonic Republic might be related to the idea of "a tightly organized community of like-minded thinkers", like the one established by Pythagoras in Croton. b) there is evidence that Plato possibly took from Pythagoras the idea that mathematics and, generally speaking, abstract thinking are a secure basis for philosophical thinking as well as "for substantial theses in science and morals". c) Plato and Pythagoras shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world". It is probable that both have been influenced by Orphism.[1]

Plato's harmonics were clearly influenced by the work of Archytas, a genuine Pythagorean of the third generation, who made important contributions to geometry, reflected in Book VIII of Euclid's Elements.

Quotes concerning Pythagoras

- "So greatly was he admired that his disciples used to be called 'prophets to declare the voice of God'...", Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, VIII.14, Pythagoras; Loeb Classical Library No. 185, p. 333

- "...the Metapontines named his house the Temple of Demeter and his porch the Museum, so we learn from Favorinus in his Miscellaneous History.", Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, VIII.15, Pythagoras; Loeb Classical Library No. 185, p. 335

- "Learn to be silent...Let your quiet mind listen and absorb..."

See also

|

|

References

Only a few relevant source texts deal with Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, most are available in different translations. Other texts usually build solely on information from these four books.

- Diogenes Laertius, Vitae philosophorum VIII (Lives of Eminent Philosophers). circa 200, which in turn reference the lost work Successions of Philosophers by Alexander Polyhistor) — Pythagoras, Translation by C.D. Yonge

- Porphyry, Vita Pythagorae (Life of Pythagoras), circa 270

- Iamblichus, De Vita Pythagorica (On the Pythagorean Life), circa 300.

- Apuleius also writes about Pythagoras in Apologia, including a story of him being taught by Babylonian disciples of Zoroaster, circa 150.

- Bell, Eric Temple, The Magic of Numbers, Dover, New York, 1991. ISBN 0-486-26788-1

- Burkert, Walter. Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism, Harvard University Press, June 1, 1972. ISBN 0-674-53918-4

- Guthrie, K.L. (Ed.), The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library, Phanes, Grand Rapids, 1987. ISBN 0-933999-51-8

- O'Meara, Dominic J. Pythagoras Revived, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1989. ISBN 0-19-823913-0 (paperback), ISBN 0-19-824485-1 (hardcover)

Notes

- ^ R.M. Hare, Plato in C.C.W. Taylor, R.M. Hare and Jonathan Barnes, Greek Philosophers, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999 (1982), 103-189, here 117-9.

External links

- Pythagoreanism Web Site

- Pythagoras, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Pythagoras of Samos, The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland

- Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, Fragments and Commentary, Arthur Fairbanks Hanover Historical Texts Project, Hanover College Department of History

- The Complete Pythagoras, an on-line book containing all survived biographies and Pythagorean fragments.

- Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, Department of Mathematics, Texas A&M University

- Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism, The Catholic Encyclopedia

- Pythagoreanism Web Article

- Pythagoreanism Discussion Group

- Occult conception of Pythagoreanism

- Pythagoras of Samos

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Tetraktys