Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosna i Hercegovina Босна и Херцеговина | |

|---|---|

| Motto: none | |

| Anthem: "Intermeco" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Sarajevo |

| Official languages | Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian |

| Government | Republic |

| Sulejman Tihić1 (Bosniak) Borislav Paravac (Serb) Ivo Miro Jović (Croat) | |

| Adnan Terzić | |

| Independence From Yugoslavia | |

• Recognized | 6 April 1992 |

• Water (%) | Negligible |

| Population | |

• July 2006 estimate | 4,498,9762 (127th3) |

• 1991 census | 4,377,033[1] |

| GDP (PPP) | 2005 estimate |

• Total | $23.65 billion (104th) |

• Per capita | $6,035 (96th) |

| HDI (2003) | 0.786 high (68th) |

| Currency | Convertible mark (BAM) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CEST) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Calling code | 387 |

| ISO 3166 code | BA |

| Internet TLD | .ba |

1Current chairman of three-member rotating presidency. 2De jure population estimate from CIA World Factbook [2]. De facto estimates are about 500,000 lower. 3Rank based on 2005 UN estimate of de facto population. | |

Bosnia and Herzegovina is a country on the Balkan peninsula of southern Europe with an area of 51,129 km² (19,741 square miles), and an estimated population of around four million people. It is known in the country's official languages as Bosna i Hercegovina or Босна и Херцеговина (in the Latin and Cyrillic alphabets respectively), although the name is commonly abbreviated to Bosnia, BiH or БиХ.

The country is a homeland to three ethnic "constituent peoples": Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats. Regardless of ethnicity, a citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina is usually identified in English as a Bosnian.

Bordered by Croatia to the north, west and south, Serbia to the east, and Montenegro to the south, Bosnia and Herzegovina is almost entirely landlocked, except for 20 km of the Adriatic Sea coastline,[1][2] centered around the town of Neum. The interior of the country is heavily mountainous and divided by various rivers, most of which are nonnavigable. The nation's capital and largest city is Sarajevo.

Formerly one of the six federal units constituting the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Herzegovina gained its independence during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. As a result of the Dayton Accords it is currently administered in a supervisory role by a High Representative selected by the UN Security Council. The country is decentralized and is administratively divided into two "entities", the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska. More recently the country has acquired many central institutions (such as ministry of defense, state court etc.) as it takes the jurisdiction back from its entities.

Bosnia itself is the chief geographic region of the modern state, with a moderate continental climate, consisting of hot summers and cold snowy winters. Herzegovina is the southern tip of the country, known for its starkly Mediterranean climate and relief. It was included first as the official name of the then Ottoman province official name in the mid-nineteenth century.

Etymology

The first preserved mention of the name "Bosnia" lies in the De Administrando Imperio, a politico-geographical handbook written by Byzantine emperor Constantine VII in 958. The Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja from 1172-1196 also names Bosnia, and references an earlier source from the year 753. The exact meaning and origin of the word is unclear. The most popular theory holds that Bosnia comes from the name of the Bosna river around which it has been historically based.[3] Philologist Anton Mayer proposed a connection with the Indo-European root bos or bogh, meaning "running water".[4] Certain Roman sources similarly mention Bathinus flumen, or the Illyrian word Bosona, both of which would mean "running water" as well.[4] Other theories involve the rare Latin term Bosina, meaning boundary, and possible Slavic origins.[4]

The origins of the word "Herzegovina" can be identified with more precision and certainty. During the Early Middle Ages the region was known as Hum or Zahumlje, named after the Zachlumoi tribe of Slavs which inhabited it. In the 1440s, the region was ruled by powerful nobleman Stjepan Vukčić Kosača. In a document sent to Friedrich III on January 20, 1448, Stjepan Vukčić Kosača called himself Herzog of Saint Sava, lord of Hum and Primorje, great duke of the Bosnian kingdom (Herzog means duke in German) and so the lands he controlled would later become known as Herzog's lands or Herzegovina.[3]

History

Pre-Slavic period

Bosnia has been inhabited at least since Neolithic times. In the early Bronze Age, the Neolithic population was replaced by more warlike Indo-European tribes known as the Illyres or Illyrians. Celtic migrations in the 4th and 3rd century BCE displaced many Illyrian tribes from their former lands, but some Celtic and Illyrian tribes mixed.[3] Concrete historical evidence for this period is scarce, but overall it appears that the region was populated by a number of different peoples speaking distinct languages.[3] Conflict between the Illyrians and Romans started in 229 BCE, but Rome would not complete its annexation of the region until 9 CE. In the Roman period, Latin-speaking settlers from all over the Roman empire settled among the Illyrians and Roman soldiers were encouraged to retire in the region.

Christianity had already arrived in the region by the end of the 1st century, and numerous artifacts and objects from the time testify to this. Following events from the years 337 and 395 when the Empire split, Dalmatia and Pannonia were included in the Western Roman Empire. The region was conquered by the Ostrogoths in 455, and further exchanged hands between the Alans and Huns in the years to follow. By the 6th century, Emperor Justinian had re-conquered the area for the Byzantine Empire. The Slavs, a migratory people from northeastern Europe, were subjugated by the Eurasian Avars in the 6th century, and together they invaded the Eastern Roman Empire in the 6th and 7th centuries, settling in what is now Bosnia and Herzegovina and the surrounding lands.[3] The Serbs and Croats came in a second wave, invited by Emperor Heraclius to drive the Avars from Dalmatia.[3]

Medieval Bosnia

Bosnian state during Ban Kulin 1180-1204

Bosnian state during king Tvrtko 1353-1391

Borders of Bosnian state in second part of 15th century

Bosnia and Herzegovina in second part of 19th century

Modern knowledge of the political situation in the west Balkans during the Dark Ages is patchy and confusing. Upon their arrival, the Slavs brought with them a tribal social structure, which probably fell apart and gave way to Feudalism only with Frankish penetration into the region in the late 9th century (Bosnia probably originated as one such pre-feudal Slavic entity).[3] It was also around this time that the south Slavs were Christianized. Bosnia, due to its geographic position and terrain, was probably one of the last areas to go through this process, which presumably originated from the urban centers along the Dalmatian coast.[3] The kingdoms of Serbia and Croatia split control of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 9th and 10th century, but by the high middle ages political circumstance led to the area being contested between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Byzantine empire. Following another shift of power between the two in the late 12th century, Bosnia found itself outside the control of both and emerged as an independent state under the rule of local bans.

The first notable Bosnian monarch, Ban Kulin, presided over nearly three decades of peace and stability during which he strengthened the country's economy through treaties with Dubrovnik and Venice. His rule also marked the start of a controversy with the Bosnian Church, an indigenous Christian sect considered heretical by both the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. In response to Hungarian attempts to use church politics regarding the issue as a way to reclaim sovereignty over Bosnia, Kulin held a council of local church leaders to renounce the heresy in 1203. Despite this, Hungarian ambitions remained unchanged long after Kulin's death in 1204, waning only after an unsuccessful invasion in 1254.

Bosnian history from then until the early 14th century was marked by the power struggle between the Šubić and Kotromanić families. This conflict came to an end in 1322, when Stjepan II Kotromanić became ban. By the time of his death in 1353, he had succeeded in annexing territories to the north and west, as well as Zahumlje and parts of Dalmatia. He was succeeded by his nephew Tvrtko who, following a prolonged struggle with nobility and inter-family strife, gained full control of the country in 1367. Under Tvrtko, Bosnia grew in both size and power, finally becoming an independent kingdom in 1377. Following his death in 1391 however, Bosnia fell into a long period of decline. The Ottoman Empire had already started its conquest of Europe and posed a major threat to the Balkans throughout the first half of the 15th century. Finally, after decades of political and social instability, Bosnia officially fell in 1463. Herzegovina would follow in 1482, with a Hungarian-backed reinstated "Bosnian Kingdom" being the last to succumb in 1527.

Ottoman era

The Ottoman conquest of Bosnia marked a new era in the country's history and introduced tremendous changes in the political and cultural landscape of the region. Although the kingdom had been crushed and its high nobility executed, the Ottomans nonetheless allowed for the preservation of Bosnia's identity by incorporating it as an integral province of the Ottoman Empire with its historical name and territorial integrity - a unique case among subjugated states in the Balkans.[5] Within this sandžak (and eventual vilayet) of Bosnia, the Ottomans introduced a number of key changes in the territory's socio-political administration; including a new landholding system, a reorganization of administrative units, and a complex system of social differentiation by class and religious affiliation.[3]

The four centuries of Ottoman rule also had a drastic impact on Bosnia's population make-up, which changed several times as a result of the empire's conquests, frequent wars with European powers, migrations, and epidemics.[3] A native Slavic-speaking Muslim community emerged and eventually became the largest of the ethno-religious groups (mainly as a result of a gradually rising number of conversions to Islam)[4], while a significant number of Sephardi Jews arrived following their expulsion from Spain in the late 15th century. The Bosnian Christian communities also experienced major changes. The Bosnian Franciscans (and the Catholic population as a whole) were protected by official imperial decree, although on the ground these guarantees were often disregarded and their numbers dwindled.[3] The Orthodox community in Bosnia, initially confined to Herzegovina and Podrinje, spread throughout the country during this period and went on to experience relative prosperity until the 19th century.[3] Meanwhile, the schismatic Bosnian Church disappeared altogether.

As the Ottoman Empire thrived and expanded into Central Europe, Bosnia was relieved of the pressures of being a frontier province and experienced a prolonged period of general welfare and prosperity.[4] A number of cities, such as Sarajevo and Mostar, were established and grew into major regional centers of trade and urban culture. Within these cities, various Sultans and governors financed the construction of many important works of Bosnian architecture (such as the Stari most and Gazi Husrev-beg's Mosque). Furthermore, numerous Bosnians played influential roles in the Ottoman Empire's cultural and political history during this time.[5] Bosnian soldiers formed a large component of the Ottoman ranks in the battles of Mohács and Krbava field, two decisive military victories, while numerous other Bosnians rose through the ranks of the Ottoman military bureaucracy to occupy the highest positions of power in the Empire, including admirals, generals, and grand viziers.[4] Many Bosnians also made a lasting impression on Ottoman culture, emerging as mystics, scholars, and celebrated poets in the Turkish, Arabic, and Persian languages.[4]

However, by the late 17th century the Empire's military misfortunes caught up with the country, and the conclusion of the Great Turkish War with the treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 once again made Bosnia the Empire's westernmost province. The following hundred years were marked by further military failures, numerous revolts within Bosnia, and several outbursts of plague.[3] The Porte's efforts at modernizing the Ottoman state were met with great hostility in Bosnia, where local aristocrats stood to lose much through the proposed reforms.[3] This, combined with frustrations over political concessions to nascent Christian states in the east, culminated in a famous (albeit ultimately unsuccessful) revolt by Husein Gradaščević in 1831.[4] Related rebellions would be extinguished by 1850, but the situation continued to deteriorate. Later agrarian unrest eventually sparked the Herzegovinian rebellion, a widespread peasant uprising, in 1875. The conflict rapidly spread and came to involve several Balkan states and Great Powers, which eventually forced the Ottomans to cede administration of the country to Austria-Hungary through the treaty of Berlin in 1878.[3]

Austro-Hungarian rule

Though an Austro-Hungarian occupying force quickly subjugated initial armed resistance upon take-over, tensions remained in certain parts of the country (particularly Herzegovina) and a mass emigration of predominantly Muslim dissidents occurred.[3] However, a state of relative stability was reached soon enough and Austro-Hungarian authorities were able to embark on a number of social and administrative reforms which intended to make Bosnia and Herzegovina into a "model colony".[5] With the aim of establishing the province as a stable political model that would help dissipate rising South Slav nationalism, Habsburg rule did much to codify laws, to introduce new political practices, and generally to provide for modernization.[5]

Although successful economically, Austro-Hungarian policy - which focused on advocating the ideal of a pluralist and multi-confessional Bosnian nation (largely favored by the Muslims) - failed to curb the rising tides of nationalism.[3] The concept of Croat and Serb nationhood had already spread to Bosnia and Herzegovina's Catholics and Orthodox communities from neighboring Croatia and Serbia in the mid 19th century, and was too well-entrenched to allow for the wide-spread acceptance of a parallel idea of Bosnian nationhood.[3] By the latter half of the 1910s, nationalism was an integral factor of Bosnian politics, with national political parties corresponding to the three groups dominating elections.

The idea of a unified South Slavic state (typically expected to be spear-headed by independent Serbia) became a popular political ideology in the region at this time, including in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[5] The Austro-Hungarian government's decision to formally annex Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 (see Bosnian Crisis) added to a sense of urgency among these nationalists.[5] The political tensions caused by all this culminated on June 28, 1914, when Serb nationalist youth Gavrilo Princip assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo; an event that proved to be the spark that set off World War I. Although some Bosnians died serving in the armies of the various warring states, Bosnia and Herzegovina itself managed to escape the conflict relatively unscathed.[5]

The first Yugoslavia

Following the war, Bosnia was incorporated into the South Slav kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (soon renamed Yugoslavia). Political life in Bosnia at this time was marked by two major trends: social and economic unrest over property redistribution, and formation of several political parties that frequently changed coalitions and alliances with parties in other Yugoslav regions.[5] The dominant ideological conflict of the Yugoslav state, between Croatian regionalism and Serbian centralization, was approached differently by Bosnia's major ethnic groups and was dependent on the overall political atmosphere.[3] Although the initial split of the country into 33 oblasts erased the presence of traditional geographic entities from the map, the efforts of Bosnian politicians such as Mehmed Spaho ensured that the six oblasts carved up from Bosnia and Herzegovina corresponded to the six sanjaks from Ottoman times and, thus, matched the country's traditional boundary as a whole.[3]

The establishment of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929, however, brought the redrawing of administrative regions into banates that purposely avoided all historical and ethnic lines, removing any trace of a Bosnian entity.[3] Serbo-Croat tensions over the structuring of the Yugoslav state continued, with the concept of a separate Bosnian division receiving little or no consideration. The famous Cvetković-Maček agreement that created the Croatian banate in 1939 encouraged what was essentially a partition of Bosnia between Croatia and Serbia.[4] However, outside political circumstances forced Yugoslav politicians to shift their attention to the rising threat posed by Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany. Following a period that saw attempts at appeasement, the signing of the Tripartite Treaty, and a coup d'état, Yugoslavia was finally invaded by Germany on April 6, 1941.[3]

World War II

Once the kingdom of Yugoslavia was conquered by Nazi forces in World War II, all of Bosnia was ceded to the Nazi-puppet state of Croatia. The Nazi rule over Bosnia led to widespread persecution. The Jewish population was nearly exterminated. Many Serbs in the area took up arms and joined the Chetniks; a Serb nationalist and royalist resistance movement that both conducted guerrilla warfare against the Nazis but also committed numerous atrocities against chiefly Bosnian Muslim civilians in regions under their control.[4] Consequently, several Bosnian Muslim paramilitary units joined the Axis powers to counter their own persecution in the hands of the Serbs in Bosnia. Most (in)famous of such units was Waffen SS Division "Handžar", numbering up to 6000 Muslim volunteers.

Starting in 1941, Yugoslav communists under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito organized their own multi-ethnic resistance group, the partisans, who fought against both Axis and Chetnik forces.[3] On November 25, 1943 the Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia with Tito at its helm held a founding conference in Jajce where Bosnia and Herzegovina was reestablished as a republic within the Yugoslavian federation in its Ottoman borders. Military success eventually prompted the Allies to support the Partisans, and the end of the war resulted in the establishment of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, with the constitution of 1946 officially making Bosnia and Herzegovina one of six constituent republics in the new state.[3]

Socialist Yugoslavia

Because of its central geographic position within the Yugoslavian federation, post-war Bosnia was strategically selected as a base for the development of the military defense industry. This contributed to a large concentration of arms and military personnel in Bosnia; a significant factor in the war that followed the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.[3] However, Bosnia's existence within Yugoslavia, for the large part, was peaceful and prosperous. Being one of the poorer republics in the early 1950s it quickly recovered economically, taking advantage of its extensive natural resources to stimulate industrial development. The Yugoslavian communist doctrine of "brotherhood and unity" particularly suited Bosnia's diverse and multi-ethnic society that, because of such an imposed system of tolerance, thrived culturally and socially.

Though considered a political backwater of the federation for much of the 50s and 60s, the 70s saw the ascension of a strong Bosnian political elite fueled in part by Tito's leadership in the non-aligned movement [[3]] and Bosnian Muslims serving in Yugoslavia's diplomatic corps. While working within the communist system, politicians such as Džemal Bijedić, Branko Mikulić and Hamdija Pozderac reinforced and protected the sovereignty of Bosnia and Herzegovina [6] Their efforts proved key during the turbulent period following Tito's death in 1980, and are today considered some of the early steps towards Bosnian independence. However, the republic hardly escaped the increasingly nationalistic climate of the time unscathed. With the fall of communism and the start of the break-up of Yugoslavia, the old communist doctrine of tolerance began to lose its potency, creating an opportunity for nationalist elements in the society to spread their influence.

The Bosnian War

The 1990 parliamentary elections led to a national assembly dominated by three ethnically-based parties, which had formed a loose coalition to oust the communists from power. Croatia and Slovenia's subsequent declarations of independence and the warfare that ensued placed Bosnia and Herzegovina and its three constituent peoples in an awkward position. A significant split soon developed on the issue of whether to stay with the Yugoslav federation (overwhelmingly favored among Serbs) or seek independence (overwhelmingly favored among Bosniaks and Croats). A declaration of sovereignty in October of 1991 was followed by a referendum for independence from Yugoslavia in February and March 1992 boycotted by the great majority of Bosnian Serbs. With a voter turnout of 64%, 99.4% of which voted in favor of the proposal, Bosnia and Herzegovina became an independent state.[3] Following a tense period of escalating tensions and sporadic military incidents, open warfare began in Sarajevo on April 6.[3]

International recognition of Bosnia and Herzegovina meant that the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) should officially withdraw from the republic's territory, although their Bosnian Serb members simply changed insignia and formed the Army of Republika Srpska. Armed and equipped from JNA stockpiles in Bosnia, supported by volunteers and various paramilitary forces from Serbia, and receiving extensive humanitarian, logistical and financial support from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Republika Srpska's offensives in 1992 managed to place much of the country under its control.[3] By 1993, when an armed conflict erupted between the Sarajevo government and the Croat statelet of Herzeg-Bosnia, about 70% of the country was controlled by the Serbs.[5]

In March 1994, the signing of the Washington accords between the leaders of the republican government and Herzeg-Bosnia led to the creation of a joint Bosniak-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This, along with international outrage at Serb war crimes and atrocities (most notably the genocidal killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak males in Srebrenica in July, 1995), eventually turned the tide of war. The signing of the Dayton Agreement in Dayton, Ohio by the presidents of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Alija Izetbegović), Croatia (Franjo Tuđman), and Yugoslavia (Slobodan Milošević) brought a halt to the fighting, roughly establishing the basic structure of the present-day state. The three years of war and bloodshed had left 250,000 people killed and more than 2 million displaced.

Politics and government

Template:Morepolitics The system of government established by the Dayton Accord is an example of consociationalism, as representation is by elites who represent the country's three major groups, with each having a guaranteed share of power. The Chair of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina rotates among three members (Bosniak, Serb, Croat), each elected as the Chair for an 8-month term within their 4-year term as a member. The three members of the Presidency are elected directly by the people (Federation votes for the Bosniak/Croat, Republika Srpska for the Serb). The Chair of the Council of Ministers is nominated by the Presidency and approved by the House of Representatives. He or she is then responsible for appointing a Foreign Minister, Minister of Foreign Trade, and others as appropriate.

The Parliamentary Assembly is the lawmaking body in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It consists of two houses: the House of Peoples and the House of Representatives. The House of Peoples includes 15 delegates, two-thirds of which come from the Federation (5 Croat and 5 Bosniaks) and one-third from the Republika Srpska (5 Serbs). The House of Representatives is composed of 42 Members, two-thirds elected from the Federation and one-third elected from the Republika Srpska.

The Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina is the supreme, final arbiter of legal matters. It is composed of nine members: four members are selected by the House of Representatives of the Federation, two by the Assembly of the Republika Srpska, and three by the President of the European Court of Human Rights after consultation with the Presidency.

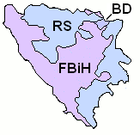

Administrative divisions

Bosnia and Herzegovina has several levels of political structuring under the federal government level. Most important of these levels is the division of the country into entities: Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina covers some 51% of Bosnia and Herzegovina's total area, while Republika Srpska covers around 49%. The entities, based largely on the territories held by the two warring sides at the time, were formally established by the Dayton peace agreement in 1995 due to the tremendous changes in Bosnia and Herzegovina's ethnic structure. These changes were caused by the ethnic cleansing of non-Serb population by the Bosnian Serb authorities,[7] the emigration and internal relocation of refugees due to the fighting, and a small influx of Croatian Serb refugees from Croatia due to the Croatian war.[8] Bosnian Serb government resettlement policy also played a part, and some resettlement took place after the war following the Dayton Agreement, subsequent to the setting of political boundaries (IEBL).[9]

Since 1996 the power of the entities relative to the federal government has decreased significantly. Nonetheless, entities still have numerous powers to themselves. The Brčko federal district in the north of the country was created in 2000 out of land from both entities. It officially belongs to both, but is governed by neither, and functions under a decentralized system of local government. The Brčko district has been praised for maintaining a multiethnic population and a level of prosperity significantly above the national average.[10]

The third level of Bosnia and Herzegovina's political subdivision is manifested in cantons. They are unique to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity, which consists of ten of them. All of them have their own cantonal government, which is under the law of the Federation as a whole. Some cantons are ethnically mixed and have special laws implemented to ensure the equality of all constituent peoples.

The fourth level of political division in Bosnia and Herzegovina are the municipalities. The country consists of 137 municipalities, of which 74 are in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and 63 in Republika Srpska. Municiaplities also have their own local government, and are typically based around the most significant city or place in the region. As such, many municipalities have a long tradition and history with their present boundaries. Some others, however, were only created following the recent war after traditional municipalities were split by the IEBL. Each canton in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of several municipalities, with the municipalities themselves further divided into local communities.

Besides entities, cantons, and municipalities, Bosnia and Herzegovina also has four "official" cities. These are: Banja Luka, Mostar, Sarajevo, and East Sarajevo. The territory and government of the cities of Banja Luka and Mostar corresponds to the municipalities of the same name, while the cities of Sarajevo and East Sarajevo officially consist of several municipalities. Cities have their own city government whose power is in between that of the municipalities and cantons (or entity, in the case of Republika Srpska).

Geography

Bosnia is located in the western Balkans, bordering Croatia to the north and south-west, Serbia to the east, and Montenegro to the southeast. The country is mostly mountainous, encompassing the central Dinaric Alps. The northeastern parts reach into the Pannonian basin, while in the south it borders the Adriatic. The country has only 20 kilometres (12 mi) of coastline,[1] around the town of Neum in the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton, although it's enclosed within Croatian territory and territorial waters. Neum has many hotels and an is important tourism destination.

The country's name comes from the two regions Bosnia and Herzegovina, which have a very vaguely defined border between them. Bosnia occupies the northern areas which are roughly four fifths of the entire country, while Herzegovina occupies the rest in the south part of the country.

The major cities are the capital Sarajevo, Banja Luka in the northwest region known as Bosanska Krajina, Tuzla in the northeast, Zenica in the central part of Bosnia and Mostar, the capital of Herzegovina.

The south part of Bosnia has Mediterranean climate and a great deal of agriculture. Central Bosnia is the most mountainous part of Bosnia featuring predominate mountains Vlasic, Cvrsnica, and Prenj. Eastern Bosnia also features mountains like Trebevic, Jahorina, Igman, Bjelasnica and Treskavica. It was here that the Olympic games were held in 1984.

Eastern Bosnia is heavily forested along the river Drina, and overall close to 50% of Bosnia and Herzegovina is forested. Most forest areas are in Central, Eastern and Western parts of Bosnia. Northern Bosnia contains very fertile agricultural land along the river Sava and the corresponding area is heavily farmed. This farmland is a part of the Parapannonian Plain stretching into neighbouring Croatia and Serbia. The river Sava and corresponding Posavina river basin hold the cities of Brcko, Bosanski Samac, Bosanski Brod and Bosanska Gradiska.

The northwest part of Bosnia is called Bosanska Krajina and holds the cities of Banja Luka, Sanski Most, Cazin, Velika Kladisa and Bihać. Kozara National Park is in this forested region.

There are 7 major rivers in the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina: The Una river in the northwest part of Bosnia flows along the northern and western border of Bosnia and Croatia and through the Bosnian city of Bihac. It is a very beautiful river and popular for rafting and adventure sports.

The Sana flows through the city of Sanski Most and is a tributary of the river Sava in the north.

The Vrbas flows through the cities of Gornji Vakuf - Uskoplje, Bugojno, Jajce and Banja Luka and reaches the river Sava in the the north. The Vrbas flows trough the central part of Bosnia and flows outwards to the North.

The River Bosna is the longest river in Bosnia and is fully contained within the country as it stretches from its source near Sarajevo to the river Sava in the north.

The Drina flows through the eastern part of Bosnia, at many places in the border between Bosnia and Serbia. The Drina flows through the cities of Foca, Gorazde and Visegrad.

The Neretva river is a large river in Central and Southern Bosnia, flowing from Jablanica south to the Adriatic Sea. The river is famous as it flows through the famous city of Mostar.

The Sava river is the largest river in Bosnia and Herzegovina but not the largest river that is flowing trough Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Sava river flows trough Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Sava is making a natural border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia and towns like Brcko, Bosanski Samac, Bosanska Gradiska lies on the river.

Discoveries

Bosnia and Herzegovina has recently been under heavy speculating due to the possible discovery of a pyramid. The alleged pyramid, located in the town of Visoko, is currently under excavation by an archaeologist named Semir Osmanagić. On April 19, digging on one side of the hill revealed large stone blocks that appear polished which Osmanagić claims are the "steps" of the pyramid. Semir Osmanagić also claims that there could be another pyramid 220 m high. This would make the Pyramid of the Sun, as it is known, the tallest as well as the oldest pyramid in the world. www.visoko.co.ba

Economy

Bosnia currently faces the dual problem of rebuilding a war-torn country and introducing market reforms to the formerly centrally planned economy. The centrally planned economy resulted in many legacies which are slowly being changed. Industry is greatly overstaffed, reflecting the rigidity of the planned economy and the slow process or transition. Under Josip Broz Tito, military industries were pushed in the republic; Bosnia hosted a large share of Yugoslavia's defense plants and a lower amount of commercially viable firms. Two major export companies in the former Yugoslavia had their headquarters in Sarajevo; UNIS holding and Energoinvest.

For the most part in Bosnia's history, agriculture has been in private hands. Farms have been small and inefficient, and food has traditionally been a net import for the republic.

As part of Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Herzegovina financed many large construction projects throughout Yugoslavia. The Highway "Bratstvo i jedinstvo", a pan-Yugoslavian project, which linked Ljubljana (Slovenia) - Zagreb (Croatia) - Belgrade (Serbia) - Skopje (Macedonia), was financed despite the lack of direct improvement to the Bosnia and Herzegovina. This project caused an increase in unemployment and a decrease in production.

The war brought about a dramatic change in the Bosnian economy. Production fell to 6%, GDP fell 75% and the destruction of physical infrastructure created massive economic trauma. While much of the production capacity has been restored, the Bosnian economy still faces considerable difficulties.

Figures from 2004 indicate that GDP both in total terms and per capita increased 10% from 2003 to 2004. While this figure, and Bosnia's shrinking national debt are positives, high unemployment and a large trade deficit are cause for concern.

The national currency is the Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark (BAM), which fixed to the Euro (€1 = KM1.95583) is very stable. The inflation rate is 1.4 as of 2005.

Yearly inflation is the lowest compared to other countries which were a part of former Yugoslavia. The inflation rate was 1.9% in 2004[11], and international debt was $3.1 billion (2005 est); making it the smallest amount of debt owed from the former Yugoslav countries (Serbia and Montenegro's international debt is $15.43 billion (2005 est), while Croatia is at $29.28 billion (2005 est)). Real GDP growth rate is 5.0% for 2004 according to the Bosnian Central Bank of BiH and Statistical Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Bosnia and Herzegovina has one of the best income equality rankings in the world, ranked at 8th among the world's 193 nations.

Overall investment value (1994-2002):

- 1994-97: 39,563,000 KM

- 1998: 55,750,000 KM

- 1999: 154,067,000 KM

- 2000: 147,214,000 KM

- 2001: 130,172,000 KM

- 2002: 321,446,000 KM

- Total (1994-2002): 805,013,000 KM

It is important to note the 247% spike in 2002 from the preceding year, illumating an ever growing interest and sense of stability foreign investors have come to trust in their investments.

The largest foreign investors (1996 - 2006) in the country have been:

- Croatia (308.444.000 €)

- Austria (279.533.000 €)

- Lithuania (252.395.000 €)

- Slovenia (236.532.000 €)

- Netherlands (204.889.000 €)

- Germany (130.984.000 €)

Foreign investments by sector:

Tourism

BiH has been a top performer in recent years in terms of tourism development; tourist arrivals have grown by an average of 24% annually from 1995 to 2000 (360,758 in 2002). According to an estimation of the World Tourism Organization, BiH will have the third highest tourism growth rate in the world between 1995 and 2020. The major sending countries in 2002 have been Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia, Germany, Italy, United States, Poland, United Kingdom, Austria, and Spain. [4]

Demographics

(Click to enlarge image for details)

Green: Predominantly ethnic Bosniaks

Red: Predominantly ethnic Serbs

Blue: Predominantly ethnic Croats

Large population migrations during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s have caused a large demographic shift in the country. No census has been taken since 1991, and none is planned for the near future due to political disagreements. Since censuses are the only statistical, inclusive, and objective way to analyze demographics, almost all of the post-war data is simply an estimate. Most sources, however, estimate the population at roughly 4 million (representing a decrease of 350,000 since 1991).

According to the 1991 census, Bosnia and Herzegovina had a population of 4,354,911. Ethnically, 43.7% were Bosniaks, 31.3% Serbs, and 17.3% Croats, with 5.5% declaring themselves Yugoslavs.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, there is a strong correlation between ethnic identity and religion because 88% of Croats are Roman Catholics, 90% of Bosniaks are Muslims and 93% of Serbs are Orthodox Christians.

According to 2000 data from the CIA World Factbook, Bosnia and Herzegovina is ethnically 48% Bosniak, 37.1% Serb, 14.3% Croat, 0.6% other.

Tensions between the three constitutional peoples remain high in Bosnia and often provoke political disagreements. Each of the three peoples are influential to roughly a same degree in Bosnia with Bosniaks being the most numerous, Serbs having their own entity, and Croats, though politically marginalized, being the strongest economically.

Education

As part of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Bosnia enjoyed a highly-developed educational system. This system not only encouraged study and higher education, but it also respected academic achievements. Two of Bosnia’s natives were awarded Nobel Prizes from this era: Vladimir Prelog, for chemistry in 1975, and Ivo Andrić, for literature in 1961; ex-Yugoslavia had three Nobel Prize winners all together, the third was Lavoslav Ružička from Croatia. This concentration of talent is remarkable in a country whose total population was severely depleted due to the diaspora of individuals fleeing during the recent war years. Bosnian college students abroad are good and recognized students; most of them attend universities in North America, Australia, and other European countries.

The recent war created a “brain drain” and resulted in many Bosnians working in high-tech, academic and professional occupations in North America, Europe, and Australia. Such situation is viewed as an economic opportunity for building a vibrant economy in today’s Bosnia. However, only few of Bosnia’s diaspora are returning to Bosnia and Herzegovina with their experience, western education and exposure to modern business practices. Most still lack professional incentives to justify widespread and permanent return to their homeland.

Bosnia’s current educational system—with seven universities, one in every major city, plus satellite campuses—continues to turn out highly-educated graduates in math, science and literature. However, they have not been modernized in last 15 years due to the war and various political and economic reasons and as a result do not meet Western educational standards which are part of criteria for EU membership. The need for reform of the current Bosnian education system is generally acknowledged although specific methods for its change have still not been formulated.

Culture

Bosnia has a rich culture with many famous persons including poets, writers and a nobel prize winner in Chemistry. One of the famous writers is Ivo Andric, a Bosnian with Croatian ethnicity who won the nobel prize in literature. He wrote the very famous book, Bridge over Drina, which was the famous Ottoman bridge over the river Drina near Visegrad, a city in the eastern part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. He wrote about the Ottomans even though he was not partial to them.

Another famous Bosnian is the Nobel prize winner Vladimir Prelog, who won the Nobel Prize in chemistry 1975. He was born in Sarajevo in 1906 and was witness to the famous assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914, the assassination that started World War I.

Sport

Bosnia and Herzegovina has produced many good sports stars. Many of them were famous in the Yugoslav national teams before Bosnia and Herzegovina's independence.

The Yugoslav national basketball team, which medaled in every world championship from 1963 through 1990, has included Bosnian stars like Drazen Dalipagic and Mirza Delibasic. Other internationally famous players from Bosnia and Herzegovina include Zoran Savic, Vladimir Radmanovic, Zoran Planinic and Aleksandar Nikolic. Bosnia and Herzegovina regularly qualifies for the European Championship in Basketball.

In football, Bosnia and Herzegovina has not qualified for a big championship yet. Mirsad Hibic, Elvir Bolic, Elvir Baljic, Meho Kodro, Sergej Barbarez, and Hasan Salihamidzic are famous Bosnian football players who have played for the Bosnia and Herzegovina national football team. The former Yugoslav national football team included famous Bosnian players, such as Josip Katalinski, Dusan Bajevic, Ivica Osim, Safet Susic, and Mirsad Fazlagic..

Bosnia and Herzegovina is the current world champion in paralympic volleyball. One thing that makes the players so respected is the fact that they lost their legs in the War of 1992-1995.

Bosnian national teams face a struggle to get all the best players born in the country to play for them. Many players born in Bosnia and Herzegovina choose to play for other countries due to their ethnic identification. For example Mario Stanic and Mile Mitic were both born in Bosnia, but choose to play for Croatia and Serbia respectively.

See also

- Lukomir

- Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bosnian Cyrillic

- Comedy in Bosnia and Hercegovina

- History of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Demographic History of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Council of Scout Associations in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Holidays of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Islam in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Jews in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- List of national parks of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Music of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Nations of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bosnian architecture

- 1991 Bosnia and Herzegovina Population Census

Gallery

-

Počitelj - Old town

-

Sarajevo - Baščaršija

-

Gradačac - City castle

-

Mostar - Kujundžiluk

-

Neum - Coastline

-

Mostar - Stari Most

-

The bridge in Višegrad also called the bridge on the drina (around 1890)

-

Sarajevo - View from east.

-

Fojnica - The Franciscan monastery

-

Ferhat-Pasha "Ferhadija" mosque in Banja Luka (1579 - 1993)

-

City-square of Bosanska Dubica

-

New "Gradska Džamija" mosque of Bosanska Dubica

-

National Library in Sarajevo

References

- ^ a b Field Listing - Coastline, The World Factbook, 2006-08-22

- ^ Bosnia and Herzegovina: I: Introduction, Encarta, 2006

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Malcolm, Noel (1994). Bosnia A Short History. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5520-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka. Sarajevo: BZK Preporod. ISBN 9958-815-00-1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Riedlmayer, Andras (1993). A Brief History of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The Bosnian Manuscript Ingathering Project.

- ^ Stojic, Mile (2005). Branko Mikulic - socialist emperor manqué. BH Dani

- ^ ICTY. Radoslav Brdjanin. Court judgement.

- ^ (December 3, 2001). Bosnian refugees returning home. CNN.

- ^ (February 21, 1996). Bosnian Serbs frantically flee Sarajevo. CNN.

- ^ OHR Bulletin 66 (February 3, 1998). - Final hearing of the Arbitration Tribunal in Vienna. OHR.

- ^ CIA WFB

External links

- Bosnian National Monument - Muslibegovica House

- Official Sarajevo Network

- Excellent BIH Tourism website

- Bosnia and Herzegovina Tourism

- Great site about Bosnia and Herzegovina-Tourism

- "Bosnia and Herzegovina". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Human Rights Archives on the Genocide in Bosnia

- Bosnia And Herzegovina Discussion

- Rape in Bosnia

- Office of the High Representative in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bosnia & Herzegovina Economy

- Bosnia and Herzegovina Map

- OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Bosnian Institute, London

- Rulers.org — Bosnia and Hercegovina List of rulers for Bosnia and Hercegovina

- Bosnia's location on a 3D globe (Java)

- A precarious peace, The Economist, 22 January 1998

Photographs

- Europe on the Matrix: Bosnia-Herzegovina — Photographs and information.